Introduction

Concerns over racial bias and discrimination in Canadian policing have been raised for decades, as demonstrated by various provincial reports dating back to the 1970s.Footnote 1 However, the issue gained federal attention following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. In response to global discussions around race and policing, the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security engaged in a comprehensive study exploring how racial bias—the favouring or preferential treatment of people from one racial group over another—may permeate through Canadian law-enforcement agencies, including within its own national police agency, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).Footnote 2 After a year-long investigation involving testimony from experts, community members, and police leaders, as well as a review of racially disaggregated data exploring interactions between the police and Black, Indigenous, and racialized communities, the Standing Committee released a groundbreaking report concluding that racial bias, but more specifically systemic racism, is and continues to be a problem within Canadian policing.Footnote 3

Systemic racism—often the result of racial bias and the perceived inferiority of racialized people—is a form of bias that is embedded within social institutions through policies, practices, and procedures that disadvantage some racialized groups while benefiting others.Footnote 4 Thus, the Standing Committee’s conclusion that systemic racism in policing is engrained within Canadian policing agencies lends additional insight into emerging evidence that suggests Black and Indigenous people, in particular, are disproportionately overrepresented in police stops and searches, excessive use of force, strip searches, and charges for minor crimes compared with their White and other racialized counterparts.Footnote 5 While much of the research exploring racial bias in Canadian policing traditionally focuses on the negative treatment and surveillance of Black, Indigenous, and other racialized people, less discussion is on who benefits. Who does not attract the attention of the police and is not perceived as a threat?

In describing how they define their work, police officers will often highlight their role as law enforcers.Footnote 6 When describing this role, they frequently stress the importance of criminal profiling and focus on “what doesn’t fit” to determine signs of suspicious activity and potential lawbreaking.Footnote 7 Although officers will argue that they are guided by their professional “instincts [when they] profile criminals,” there are concerns that these instincts are influenced by racial and class biases.Footnote 8 To illustrate, in a Canadian study exploring law enforcers’ perceptions of where crime is more likely to occur, when describing a high-priority neighbourhood that is distinguished as having a high crime rate—an impoverished area in Toronto, Canada—an officer states: “[in] Jane and Finch traditionally […] there is a mostly black or immigrant population there […] certainly not typical white. And if that is where the crime is […] go where the fish are if you’re going to catch fish.”Footnote 9

While this declaration does not explicitly state that Black and other racialized people are criminals (although it comes close), the officer’s statement exemplifies what legal researchers have argued for decades—that the colour of justice is White.Footnote 10 They maintain that “if you are not white, you face a much greater risk of attracting the attention of law enforcement officials.”Footnote 11 Further, while differentiating criminality from “typical White” people, the officer’s statement reveals that differential enforcement may be based on not only race, but also social class. Therefore, with emerging studies suggesting that Black, Indigenous, and racialized communities are subject to increased police surveillance due to their race, this raises critical questions into how Whiteness, and to an extent socioeconomic status, may serve as a benefit and protection from the police gaze.

This line of inquiry is an area of interest, as a growing subset of criminologists argue that the discussion surrounding race and crime is narrow in focus when comparisons are made between Black (and/or racialized) and White racial categories.Footnote 12 As a result, discussions around race and policing fail to view any differences in individual characteristics within these racial categories. They argue that there is a hierarchy of Whiteness, and that a White person’s position in society and perceived criminality within law enforcement are also influenced by contextual factors, including geographic location, gender, and socioeconomic status.Footnote 13 While it is acknowledged that, regardless of intersecting factors such as gender, sexual orientation, and abilities, for Black, Indigenous, and racialized people, their race is a master status that is most likely to attract police attention, some scholars argue that intersecting factors among White people do influence police interactions.Footnote 14 To illustrate, in their review of the 2011 Bureau of Justice and Statistics Police-Public Contact survey, researchers Motley Jr. and Joe found that Black men and boys with an income of under $20,000 were most likely to experience excessive use of force by the police, but being male and within a similar lower socioeconomic status also increased the risk of exposure to police use of force among White residents.Footnote 15 Highlighting this finding is in no way meant to undermine the mounting evidence that supports the notion that law-enforcement officials’ stop-and-search practices, as well as engagement in excessive force, disproportionately impact Black and racialized populations; rather, this finding suggests that there may be a hierarchy within White populations in which the “typical White” (i.e. a cis-gender, heterosexual, and within a higher socioeconomic bracket) is rendered non-threatening and therefore avoids scrutiny from the police. Might race and class biases impact police decisions? If so, may police surveillance and documentation practices involving higher-classed White people differ from those of Black, Indigenous, and racialized people in Canada? An examination into formal police documentations involving the perpetrator of Canada’s worst mass shooting in history aims to explore this further.

Nova Scotia’s Mass Casualty Event and AftermathFootnote 16

On the evening of 18 April 2020, the RCMP received numerous calls reporting multiple shootings and house fires in the small rural community of Portipique, Nova Scotia, Canada. Over the course of thirteen hours, a man, who is now identified as the perpetrator,Footnote 17 murdered twenty-one civilians (one of whom was carrying an unborn child) and an RCMP officer, bringing the death toll to twenty-two. On 19 April, the perpetrator—a successful White male denturist who resided in a rural beachside community in Nova Scotia—was shot and killed by an RCMP officer. This brought to an end not only Canada’s worst mass shooting, but also one of the longest in duration. Despite police reports indicating that “fairly early into the RCMP’s involvement, [they] learned of a possible suspect” (Public Safety Canada, 27 April 2020), the police had few documented details on the perpetrator to assist in their initial investigation.Footnote 18 This led to critical questions as to why there were so few police-recorded details when emerging evidence suggests that the perpetrator had a very violent and turbulent past, and should have, by all accounts, been formally identified by the police as a danger to the public.Footnote 19

Following sustained calls from the families and supporters of the victims for a fulsome public inquiry following the mass casualty event, the Mass Casualty Commission (MCC)— a joint federal and provincially funded public inquiry—was formed on 21 October 2020. The MCC set out to understand “the causes, context and circumstances giving rise to the April 2020 mass casualty; The responses of police, including the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), [and] municipal police forces.”Footnote 20 I was hired by the MCC to work alongside the Director of Research and Policy to provide a sociological analysis of gender, class, and racial biases that influence police procedures and thus may have played a role in the RCMP’s response during the early stages of their investigation. In this capacity, I had access to most MCC documentary records, including police interactions with the perpetrator prior to the mass casualty event. It is these records that allow an analysis of how the perpetrator—a violent White man who had high professional and financial status—had largely escaped intense police attention for years.

Using critical discourse analysis, the following case study into the Nova Scotia mass casualty event will argue that the perpetrator’s race and social-class status allowed him to escape formal surveillance, resulting in a police investigation that has now been deemed “a disastrous failure.”Footnote 21 By comparing documented police interactions involving the perpetrator with the experiences of Black Nova Scotians—who for decades have raised concerns related to differential police treatment, resulting in the over-surveillance and criminalization of people within their communities—this contrasting approach aims to demonstrate the ways in which formal police documentation practices reflect and perpetrate differential treatment by the police.

In the pages that follow, I will provide a brief review of the literature demonstrating that Black, Indigenous, and other racialized people are over-surveilled by Canadian law enforcement. The section intends to demonstrate that higher levels of police surveillance impact all people who identify as Black, Indigenous, and racialized, and perpetrates societal perceptions of danger within these communities. To further support this argument, I review two high-profile inquiries into police conduct in Nova Scotia, including the Halifax Street Check Report, which explores Halifax Regional Police contact data involving Black, White, and racialized Nova Scotians, as well as the narratives of Black Nova Scotians, outlining their lived experiences with law-enforcement officials. In tandem, I draw on documentary police records, gathered by the MCC. Through a critical discourse lens, a review of formal police documents detailing contact with the perpetrator prior to the mass casualty event aims to demonstrate that the perpetrator’s Whiteness and social status deemed him safe, thus making him invisible to the police during the early stages of the RCMP’s investigation. By contrasting Black Nova Scotians’ experiences of law enforcement with those of the perpetrator, the following paper will demonstrate that institutional procedures and processes, influenced by biases, not only produce and maintain racial disparities within the criminal justice system, but also negatively impact law-enforcement officials’ ability to conduct fair and thorough criminal investigations, ultimately impeding public safety.

Literature Review

Systemic Racial Bias in Canadian Policing: Racial Profiling

An area that has garnered increasing attention in Canada to demonstrate the issue of racially biased policing involves an exploration into street checks and police stops. Street checks are best understood as an involuntary interaction between a police officer and a citizen in which an officer may ask a citizen to voluntarily provide identifying information for criminal investigations, even if that person is not engaged in any unlawful conduct.Footnote 22 Police stops are best understood as the discretionary rights afforded to law-enforcement officials in Canada. Police officers have the legal right to stop any citizen whom they deem to be a suspect in a crime or engaging in criminal activity. Further, the police have the right to stop citizens who are driving if they believe that they have committed a driving offence or are driving under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol, or to ensure that a citizen has the proper documentation to drive.Footnote 23 In essence, both street checks and police stops are phenomena that document who draws the attention of the police or who the police perceive as being a public safety concern.

Emerging evidence suggests that increased police surveillance in racialized communities, as well as the documentation of Black, Indigenous, and other racialized people, may contribute to their overrepresentation within the criminal justice system. Concerns over racial profiling in which the race of an individual draws police attention rather than engagement in criminal behaviour have been supported by several Canadian studies.Footnote 24 One of the earliest studies used the Toronto Youth Crime Survey, which included a random sample of 4,000 Toronto high-school students, to explore how often survey respondents had been stopped, questioned, and searched by the police. Gross racial differences emerged in which 51 percent of Black high-school students reported that they had been stopped by the police multiple times over the past two years compared with 23 percent of their White counterparts, 11 percent of East Asian students, and, finally, 8 percent of South Asian students over two years.Footnote 25 While critics of the study argued that race is not the only factor to attract police attention—other issues include youth living in highly populated or high-crime communities, engagement in public leisure, driving frequency, and, more importantly, youth engagement in criminal behaviour—the authors of the study found that racial differences concerning police contact remained even after controlling for gender, social class, frequency in engaging in social leisure activities, neighbourhood characteristics, drug and alcohol use, and self-reported criminal behaviour.

Though the authors did find that youth who report a high level of deviance are more likely to be stopped and questioned by law-enforcement officials, which is consistent with the police argument that they focus on criminal activity, lack of engagement in crime did not lessen police attention on Black youth. When controlling for offending, the authors found that the effect of race became stronger. In other words, all Black youth were most likely to encounter police, including those with minimal or no involvement in criminal activity. Similar results have been reported in other Canadian studies.Footnote 26 All authors conclude that Black youth do not benefit from the same protective presumption of innocence as their White counterparts. Thus, compliance with the law does not shield all racial groups from police attention equally. The findings point to a systemic issue within policing practices in which race appears to be a significant factor influencing the frequency of police stops and searches.

Street Check/Carding Data

Studies that involve police data, which also provide evidence of racial profiling, are those that examine street check or carding data, as well as studies that examine racial disparities regarding police traffic stops. Even though street check incidents do not involve illegal activity, the police can record personal information for intelligence purposes. While law-enforcement officials defend the practice of street checks as being essential for intelligence-gathering on potentially suspicious activities, the disparity in the rates at which they are conducted has raised concerns.Footnote 27

To illustrate, a decade-long analysis of Toronto Police Service (TPS) police street checks showed disproportionate stops involving Black people compared with their White counterparts.Footnote 28 The data suggest that Black people were most likely to be stopped and street checked in either White neighbourhoods or areas with high crime rates. While the practice has been supported as a mechanism that assists with criminal investigations, there has been little evidence to suggest that street checks lead to more arrests or charges. Further, a provincially funded review of the TPS Street Check data from 2007 to 2012 demonstrated that the service conducted and recorded approximately 2 million street checks or, on average, 400,000 street checks per year.Footnote 29 As expected, the data suggest that the street check rate for Black men and boys was almost eight times higher than those for their White counterparts, and almost two times higher than those of their other racialized counterparts, including South Asian, Hispanic, and Middle Eastern men and boys, combined. As such, members of the Black community are most likely to garner police attention. The overrepresentation of Black people in police stops has been defended by law enforcement with the claim that Black and racialized people have a higher likelihood of being involved in certain types of crime; however, data to support these assertions have not been empirically supported.Footnote 30 Instead, Black people in Canada have voiced that police investigative practices feel invasive and discriminatory.Footnote 31

Traffic Stops

Another form of police analysis involves a review of traffic stops. As part of a provincial human rights agreement, the Ottawa police were mandated to explore racial disparities in their traffic stops.Footnote 32 The data suggest that racialized men and boys are more likely to be stopped by the police. The Ottawa data demonstrate that Middle Eastern and Black men and boys are more likely to be stopped by law-enforcement officials—Middle Eastern men and boys are six times more likely to be stopped than their White counterparts, while young Black men and boys are five times more likely to be stopped. These findings have been replicated in studies across various Canadian jurisdictions, including in Montreal, Edmonton, Vancouver, and Thunder Bay, demonstrating that Black, Indigenous, and other racialized people are much more likely to be subjected to involuntary police contact than their White counterparts.Footnote 33

Suspicion in the Eyes of Law Enforcement

Modern policing, as an institution, traces its origins to the United Kingdom in the nineteenth century and has influenced the structure and processes of the police in Canada, the United States, and Australia.Footnote 34 Historically, the institution has been dominated by White men. Scholars suggest that this imbalance has profoundly shaped the culture within police agencies, often creating environments in which the norms, values, and behaviours associated with Whiteness and masculinity not only are valued internally, but also influence external behaviours, such as interactions with citizens.Footnote 35 Critical police cultural researchers suggest that the overwhelmingly White (and masculine) nature of police institutions creates a culture in which anything outside of these perceived norms is viewed with suspicion or hostility.Footnote 36 Thus, when suspicion is used as a guiding factor when making surveillance decisions, a growing body of Canadian research suggests that race, ethnicity, and gender can influence police perceptions concerning criminality, ultimately shaping citizen interactions, surveillance, and arrest decisions.Footnote 37

The broader literature, however, suggests that socioeconomic status and gender can influence police–citizen interactions as well.Footnote 38 To illustrate, in their qualitative study exploring racial identity and police interactions among a racially diverse group (including Black and White participants), Dottolo and Stewart found that those most likely to report negative police interactions and discriminatory surveillance by law-enforcement officials were Black men and boys of a lower socioeconomic status rather than White respondents of a higher socioeconomic status.Footnote 39 The authors argue that stereotypical perceptions of criminality among African American populations may influence how the police interact with Black people, including heightened surveillance and harsher discretionary arrest decisions. The authors suggest that their findings demonstrate that White men and boys of higher socioeconomic class do not fit stereotypical perceptions of criminality and therefore may not ignite police “suspicion.” These findings echo a quantitative study conducted by Geiger-Oneto and Phillips exploring the phenomenon known as “driving while Black,” which suggests that race is more likely to influence a police officer’s decision to stop a driver for police investigations.Footnote 40 The authors, however, also explored the intersection of race, gender, and class. In their survey of 1,192 undergraduate students at a diverse American college about their experiences with the police as well as their criminal behaviour, the authors found that race, gender, and socioeconomic status influenced police interactions. Survey results suggested that African American and Hispanic men were more likely to be pulled over and questioned by the police while driving in comparison with their White counterparts. This is despite the fact that White men were more likely to report that they were carrying drugs in their vehicles. Further, participants (both White and Black) who reported a lower socioeconomic status were more likely to be stopped and questioned by law-enforcement officials while driving, suggesting that class may also influence the likelihood of being stopped, questioned, and arrested by the police.

The existing research on race, gender, class, and police decision-making highlights that racial and socioeconomic factors interact in nuanced ways, affecting police behaviour and perceptions of who engages in crime. From this literature, it may be possible to infer that White men from middle to upper socioeconomic backgrounds do not fit the typical profiles that are subject to police scrutiny and thus enjoy a form of “shielding” due to their race, gender, and social standing. While most studies exploring race and policing concentrate on the biased treatment of Black individuals and other marginalized groups by law enforcement, the following study seeks to understand how such discrimination not only damages these communities, but also broadly jeopardizes public safety by ignoring the “non-traditional” (or White) suspects. To illustrate this point, through critical discourse analysis, I will examine official police records of interactions between the police and the perpetrator who was responsible for the deadliest mass casualty event in Canada before the deadly shootings. Despite the growing body of evidence which suggests that the perpetrator was a violent person towards family, friends, and other members of the public, law-enforcement officials failed to record him as a public danger. This disparate treatment in comparison with that of people within Black, Indigenous, and racialized communities suggests that racially biased monitoring and documentation practices may have affected the ability of the police to conduct a thorough investigation in the beginning stages of the mass casualty event. As such, the following study will explore whether the perpetrator’s Whiteness and socioeconomic status rendered him a non-threat in the eyes of law enforcement.

Setting Description

The loss of twenty-two lives at the hands of a sole perpetrator drew profound sorrow and outrage as grieving families of the victims, legal experts, academics, and the public sought an explanation for how such a tragedy could have occurred. Initial requests for a public examination of the RCMP’s investigative actions during and after the mass casualty event were declined. Instead, a joint provincial and federal independent review of the events was approved. However, shortly after this decision, upon renewed calls from the families of the victims, political supporters, and the public, a federal decision was made to conduct a full public inquiry.Footnote 41 This decision gave the Inquiry Commissioners independent power to summon witnesses to present evidence, either verbally or in written form, under oath, and to acquire any documents or items that were deemed essential for a thorough investigation within a public forum.Footnote 42 Ultimately, the public nature of the inquiry meant that there would be not only a critical review into the RCMP’s response during and following the mass casualty event, but also a review of Canadian law-enforcement procedures in Canada, free from government or police intrusion. This decision was particularly significant due to a scarcity of critical research into Canadian police processes and procedures, often due to a barrier to accessing data that may give reason to criticize police functions and/or actions.Footnote 43

To illustrate, access to data that allow a thorough exploration of how police practices may differ among racially diverse communities in Canada has been particularly difficult to obtain. This is due to historical informal and formal bans on the collection and dissemination of racially disaggregated police data.Footnote 44 While this is changing (please see the RCMP’s 2023 commitment to collect and analyze race-based data), much of the knowledge around racial bias in Canadian policing has been the result of commissioned reports. This includes the Halifax Street Check Report—a comprehensive study exploring the experiences of Black Nova Scotians with the police in Halifax, released by the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission (NSHRC) one year before the mass casualty event.Footnote 45

The roots of the report can be traced back to a police-initiated stop involving Kirk Johnson—a Black professional boxer and Olympian from North Preston, Nova Scotia. Johnson was stopped in his Ford Mustang by a Halifax Regional Police Service (HRPS) officer on 12 April 1998. The officer requested Johnson’s proof of insurance and vehicle registration. Despite producing the requested documents, Johnson was issued a ticket and his car was towed. The following day, a police official found the impoundment of Johnson’s vehicle to have been unjustified and ordered the release of the car. Johnson lodged a complaint with the NSHRC, alleging racial profiling by the HRPS. Johnson won his case, confirming that he was racially profiled.Footnote 46 As a remedy, the HRPS was mandated to undertake a study into racial profiling to explore “the role of race in traffic stops by Halifax Regional Police”; however, the ruling was ignored by the police and unenforced by the NSHRC.Footnote 47

In 2016, the Canadian Broadcast Corporation (CBC) began an investigation into the impact of Johnson’s case on policing in the Halifax region. The CBC requested to see the results of the traffic stop study that the Human Rights Tribunal had recommended; however, the HRPS was unable to produce the study, as it had never been conducted. Instead, because of the CBC request, the HRPS released a report on race and police street checks. The report revealed that Black people were grossly overrepresented in the street check statistics of the HRPS. Public outrage over police surveillance, racial profiling, and the criminalization of Halifax’s Black community ensued, leading to the full NSHRC inquiry into the relationship between race and police street checks in Halifax.Footnote 48

The Halifax Street Check Report provides both relevant and localized context for the current study’s exploration, as the results lean towards a broader racialized analysis on who is deemed suspicious within the context of Canadian policing. If members from Black, Indigenous, and racialized communities are identified as dangerous and thus more likely to be subjected to higher rates of aggressive police surveillance and documentation practices, then this may explain why the perpetrator in the mass casualty event—a White man of higher socioeconomic status—went unnoticed by the police for so long.

Theory and Methods

Critical Discourse Theory

Critical discourse analysis offers both a theoretical and a methodological framework to examine discourse within social and cultural environments.Footnote 49 The analysis aims to demonstrate how values, attitudes, beliefs, and ideals are shared, shaped, and reshaped through written, spoken, or visual language. Researchers who utilize critical discourse analysis often intend to demonstrate how power and marginality are expressed through everyday language within a social environment. Critical discourse analysis is defined as: “an approach that systematically identifies often opaque relationships of determination between discursive practices, events, and texts, with broader social and cultural structural relations and processes, and how the opacity of these relationships between discourse and society is itself a factor in securing power and hegemony.”Footnote 50

In other words, a critical analysis of language seeks to explore how power is woven within discourse and how norms are produced through language. Critical discourse analysis is often used within a macro-social analysis of social practice to understand how language shapes reality in wider social power structures.Footnote 51 The Mass Casualty Commission’s mandate to understand the systemic contextual factors that may have led to the event provides a unique case study through which to examine how perceptions of criminality influenced by race, gender, and class may have helped the perpetrator to evade negative police attention for decades, despite evidence that suggests the perpetrator was a violent individual who should have, by all accounts, been formally identified by the police as a dangerous citizen.Footnote 52

To explore the perpetrator’s interactions with law-enforcement officials in Nova Scotia, I requested access to all documents received by the MCC showing historical and documented contact between the police and the perpetrator. Following this request, I gained access to a list of all Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) checks related to the perpetrator. CPIC checks are often used to determine an individual’s criminal history through a review of the National Repository Criminal Record system. The CPIC check also includes any non-criminal checks made on an individual (based on name and date of birth) by other national or local law-enforcement officials.Footnote 53 Further, I reviewed two separate reports, both dated 20 February 2020, outlining formally documented police interactions. My overall review confirmed that the perpetrator did not have a criminal record and very few formal records outlining problematic behaviours.Footnote 54

This is in stark contrast to the experiences of Black and Indigenous people in Nova Scotia.Footnote 55 This assertion is based on a review of documented police incidents, as well the personal stories of Black Nova Scotians shared through community consultations in the Halifax Street Check Report. The report provides further insight into how Black people in Nova Scotia are subjected to increased police attention, the formal documentation of their interactions, as well as experiences with violent use of force.

Analysis

Historical Evidence of the Perpetrator’s Violent Past

Stories emerging from close family members, former romantic partners, coworkers, and neighbours suggest that the perpetrator had a very troubled and violent past involving physical and sexual assaults, uttering threats, intimidation, and having illegal firearms, yet he seemingly avoided arrest or any significant legal consequences of his actions.Footnote 56 At the time of the mass casualty event, there were few police records demonstrating or documenting the perpetrator’s criminal behaviour. While the data suggest that reporting experiences concerning violence committed by a family member, friend, or acquaintance to the police are low, regarding the perpetrator, some family members, friends, and neighbours made concerted attempts to report the perpetrator’s violent and irrational behaviour, as well as his potential possession of illegal firearms, to the police.Footnote 57 To illustrate, evidence now suggests that neighbours repeatedly reported that the perpetrator had illegal weapons and would openly threaten his common-law spouse, Lisa Banfield. Further, following an anonymous public tip that the perpetrator was in possession of illegal guns and wished to “kill a cop” in 2011, a police bulletin was sent to the RCMP but no significant action was taken to confiscate his weapons or charge him with a crime. Therefore, there were many historical allegations raised against the perpetrator but they resulted in minimal police intervention.Footnote 58 A notable incident that illustrates this involves an attempt to report the perpetrator for violent and suspicious behaviour by Brenda Forbes, a former friend and neighbour of the perpetrator.

Following the mass casualty event, Brenda Forbes told the RCMP and Mass Casualty investigators that she had reported a domestic assault incident between the perpetrator and his common-law spouse, Lisa Banfield, in 2013 (see Violence toward Spouse Foundational Document, 2022, for further details). Furthermore, Forbes stated that she had also called the police due to her concerns that the perpetrator was in possession of a large quantity of illegal weapons, but there was minimal follow-up.Footnote 59 Forbes recalls that an RCMP officer did respond to the call but decided not to move forward without direct information from Lisa Banfield. According to Forbes, the officer expressed that “there’s not much we can do ‘cause we don’t have her side of the story.” In relation to concerns over the perpetrator’s having illegal weapons, Forbes recalls the officer’s expressing that the police would not move forward because “we have no proof.”Footnote 60 A review of formal police documentation supports this. While the RCMP officer conducted a simple CPIC check on the perpetrator, there was no indication that Forbes’s relay of information relating to the perpetrator’s potential involvement in violence or illegal possession of firearms was added to the police database. This lack of documentation is worth noting. The RCMP’s Street Check policy allows the police to document police–civilian encounters or observations that officers perceive to be of “intelligence value.” More specifically, the policy specifies that the police can gather and record information on “legitimate public safety reasons.”Footnote 61 However, what is perceived as “legitimate” is often based on individual officer discretion and is susceptible to bias.Footnote 62

The case of the perpetrator’s avoiding arrest for domestic abuse and other violent behaviours may be viewed through an examination into both gender and class bias, as he was a successful male denturist who owned multiple properties, indicating significant financial resources. First, this financial stability may have influenced how the police perceived the perpetrator, potentially viewing him as a “respectable” citizen who was less likely to be involved in criminal activities. This is supported by the broader literature which suggests that citizens of a higher social status often receive more lenient treatment from law-enforcement officials.Footnote 63 Some researchers suggest this may be the result of unconscious or conscious biases that influence perceptions of criminality. These researchers argue that class bias ultimately influences how officers perceive and thus interact with individuals from higher-classed communities. They are treated favourably, while those from lower-classed communities are treated more harshly.Footnote 64

It is also worth noting the role that gender may have played in the lack of police response, particularly as it relates to domestic violence. Stereotypes related to masculinity tend to normalize or excuse aggressive behaviour in men by seeing it as less alarming or less indicative of future violence.Footnote 65 This stereotype might have led police to underestimate the threat the perpetrator posed. Feminist scholars have demonstrated that, historically, domestic violence cases have been underreported and under-investigated, particularly when the perpetrator is male. Domestic violence is often viewed as a private matter rather than a serious crime. Further, there is a tendency to blame the victim, particularly when the victim is a woman, resulting in the police taking complaints less seriously and questioning the victim’s credibility.Footnote 66 As such, when considering Forbes’s relay of information about the perpetrator, class and gender privilege may have provided the perpetrator with the benefit of the doubt and protection from further police attention. However, an examination into the role of race is also relevant. Understanding the experiences of Black people in Nova Scotia provides further context.

Race and the Police in Nova Scotia

Analysis of official Halifax Regional Police street check data presented in the Halifax Street Check Report indicate that Black people in Halifax are disproportionately subject to street checks, with rates that are significantly higher than those of their White counterparts. To illustrate, despite representing 3.7 percent of the population, the street check rate for Black people between 2006 to 2016 was 156 per 1,000, compared with 25 per 1,000 for White people. The rate for Black men and boys was particularly high at 276 per 1,000—much greater than that for White men and women. Factors such as criminal history or residing in high-crime areas did not explain the racial disparities in street checks, which persisted across all areas of Halifax.Footnote 67 Much like the results from other Canadian police service data, the rate of street checks for Black people was higher in predominantly White neighbourhoods with low crime rates compared with neighbourhoods with higher crime rates and larger Black populations, ultimately supporting the notion that Black people draw more attention in spaces in which it is perceived that they do not belong.Footnote 68

After the release of the Halifax Street Check Report, the RCMP in Nova Scotia continued to support the use of street checks, arguing that they “are a valuable investigative tool that allows the storing and sharing of information related to crime and public safety issues [… and] initiate and support investigations, and identify crime trends” despite there being no evidence to support the argument that street checks drastically reduce crime.Footnote 69 To illustrate, increased street check activity is related to small but statistically significant increases in both crime counts and crime severity. Instead, the data support the notion that increased levels of police surveillance are a factor in the criminalization of the Black community in Nova Scotia, as the data indicate that nearly one-third of Black men and boys in Halifax (30.9%) were recorded and charged with at least one criminal offence, which was in stark contrast to just 6.8 percent of their White counterparts during the same period of review.Footnote 70

Differential Treatment in Police Interactions

Many Black Nova Scotians who participated in community consultations for the Street Check report were able to draw on lived experiences to demonstrate that Black people who do not comply with police requests to provide their personal information are physically threatened by an officer or subject to harsh treatment and risk a criminal charge. To illustrate, a young Black man stated the following:

I was coming home from work wearing a hoody with a skull on it. A police officer stopped me […] In a very angry way, he asked for my name and my ID. I refused to give him my name. He said “if you don’t give me your name, I’m gunna arrest you. We can do this easy or we can do this hard.” I felt intimidated. I didn’t want to get arrested, so I gave him my info. He checked me out and let me go. I felt like I had no power. I was really mad.Footnote 71

Another young Black man recalls his encounter with the police:

I was leaving a party close to the university. It was night and very quiet on the street […] I did jaywalk, but anybody would at that time of night on a residential street with no traffic. Then a police car approached and stopped me. The officer started to ask me questions and asked for my ID. I know my rights and I refused […] Then I was grabbed by the cop and thrown to the ground and handcuffed. I asked what I did wrong and the officer would not tell me. I found out later that I was charged with obstruction […] I filed a complaint. Lucky my Dad knows the Police Chief and the charges were dropped.Footnote 72

These selected experiences greatly differ from the few documented police interactions between the police and the perpetrator.

Documented Police Interactions With the Perpetrator

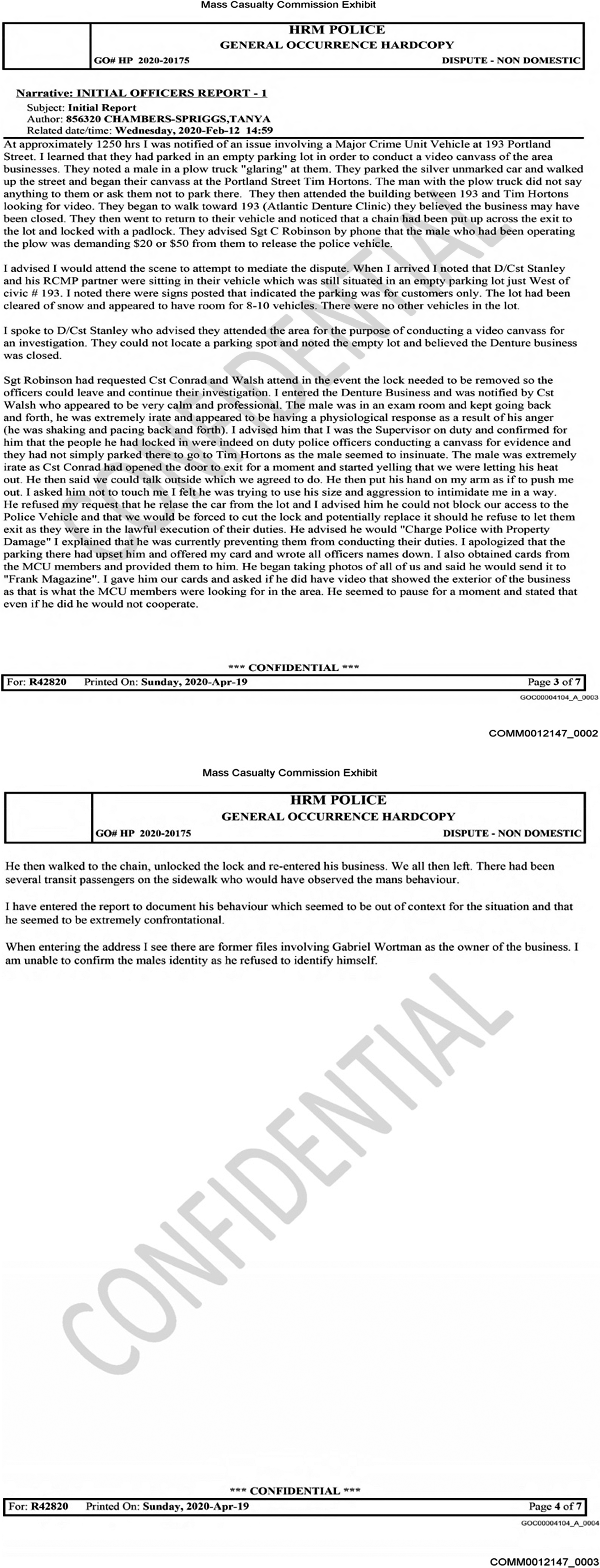

On 12 February 2020, two months before the mass casualty event, an HRPS Supervisor on duty was called to assist in a volatile interaction between the police and the perpetrator (See figure 1). An HRPS officer and an RCMP officer were conducting a video canvass for an investigation that also happened to be in the same location as the perpetrator’s dentistry business. The HRPS and RCMP officers had parked their unmarked vehicle in what appears to have been a parking space reserved for dentistry clients. The perpetrator was quite upset and in response “put a chain across the exit to the lot and locked with a padlock” (Halifax Regional Police, General Occurrence 2020-20175, 3), ultimately impeding the officers from leaving the area and continuing their investigation. The HRPS Supervisor attended the scene to advise the perpetrator that he had confined on-duty police officers who were conducting an investigation. The perpetrator did not seem fazed. The Supervisor notes that the perpetrator was “irate” and physically “put his hand on my arm as if to push me” (p. 3). The perpetrator refused to cooperate and unlock the padlock, and yelled that he would “charge police with property damage” (p. 3).

Figure 1. General Occurrence Report Involving the Perpetrator.

In this case, the police have a valid reason to charge the perpetrator with obstruction of justice (Criminal Code, 139[1]) but, instead, the Supervisor notes that they apologized (emphasis added by author) to the perpetrator for upsetting him and provided the perpetrator with the names and contact information of all officers on scene.Footnote 73 At this time, the perpetrator unlocked the lock and went back to work. The police then left, without gathering the name of the perpetrator or suggesting a formal charge for his behaviour. Instead, the Supervisor noted the incident due to the perpetrator’s “behaviour which seemed out of context for the situation […] and seemed extremely confrontational.” The Supervisor was “unable to confirm the male’s identity as he refused to identify himself.” Interestingly, no officer on the scene felt it was important to gather any personal information on the perpetrator—even his name. Only after the incident, during a search of the business address, did the HRPS Supervisor identify the perpetrator by name.

The documented incident involving the perpetrator and the police is in stark contrast to the experiences of many Black Nova Scotians. Even though, in this incident, the perpetrator refused to give his name to the police on the scene, defied police requests, knowingly interrupted a police investigation, was noted as “intimidating,” and aggressively handled a law-enforcement official, the police did not pursue the incident or criminally charge the perpetrator. So, while Black Nova Scotians fear the police and feel forced to provide their personal information if stopped for “intelligence purposes” or else risk possible criminal charges, it is clear that the perpetrator did not fear similar retribution.

Incident 2

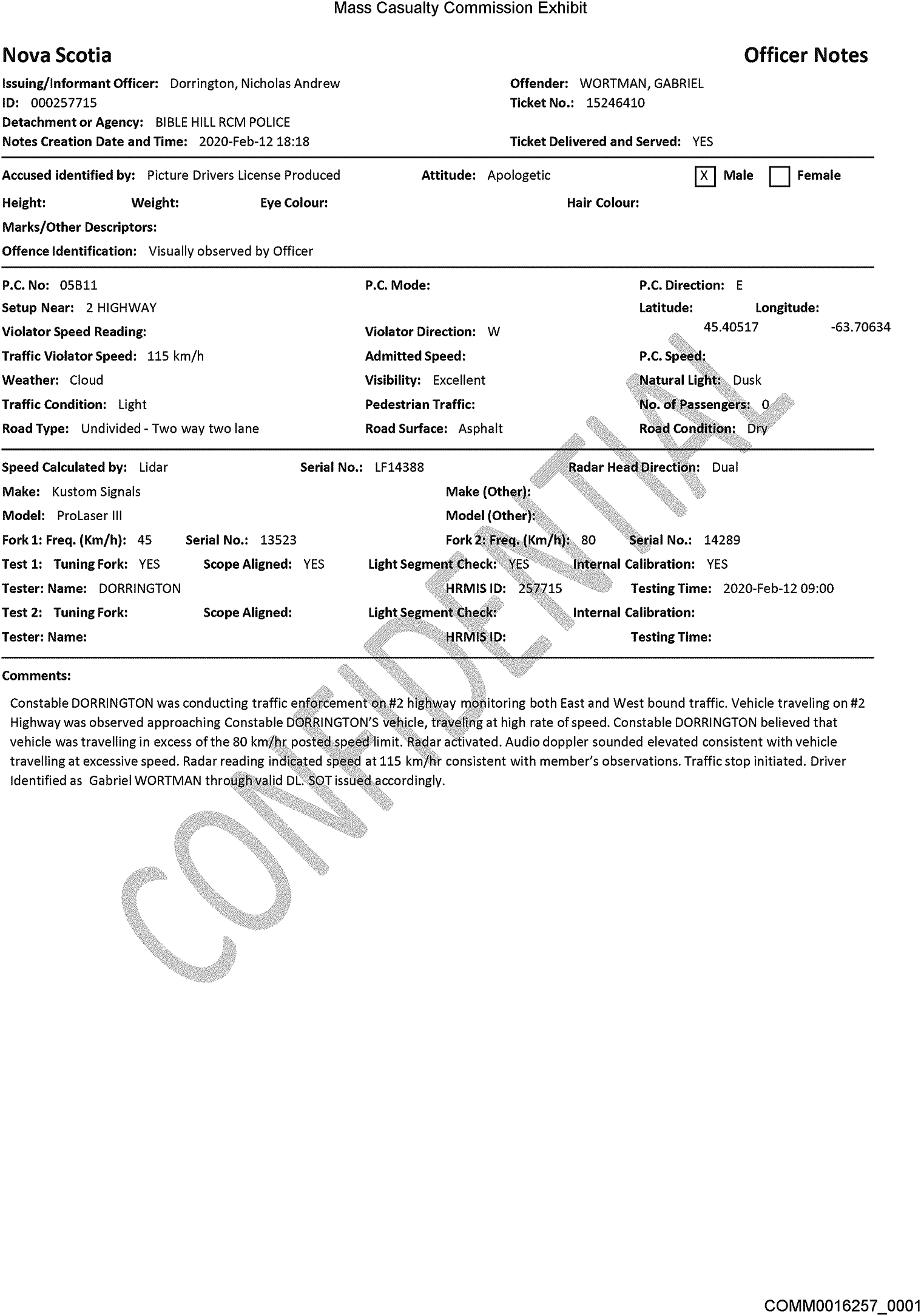

Coincidentally, on the same evening, after the incident with the HRPS, the perpetrator was stopped by an RCMP officer for speeding. In his interview with MCC investigators, the officer notes that, while he was on patrol in Portipique (the rural beachside community where the perpetrator resided), the officer spotted a speeding White Taurus that “looked like an RCMP Taurus with the subdued markings” and decided to initiate a stop.Footnote 74 The officer reports, in his mass casualty interview, that the perpetrator exited his vehicle and walked towards the police car in a manner that the officer describes as “aggressively confrontational […] like he was looking for a fight.”Footnote 75 The officer instructed the perpetrator to return to his vehicle, which he did. The officer recalls that, when he approached the suspect’s car, the perpetrator initially spoke like a “conspiracy theorist,” implying “we’re all working together.”Footnote 76 This may have been related to the perpetrator’s earlier encounter with the HRPS; however, as noted, the RCMP officer was not aware of this encounter and only stopped the perpetrator for speeding. Once this was explained, the perpetrator seemingly complied with the officer’s requests by providing his licence, registration, and insurance. The officer states that the perpetrator began to engage in non-confrontational banter and spoke of his collection of Taurus vehicles and RCMP paraphernalia. The officer indicated that he did not think much of it and continued to issue the perpetrator a traffic ticket. The perpetrator was sent on his way.

The official documentation of this incident is worth noting. The speeding ticket records that, at the time of the incident, the perpetrator’s attitude was “apologetic” despite his being aggressive and confrontational upon the initial stop (see Figure 2). Thus, once again, the police deemed the perpetrator to be a non-threat—a person who was not worth formally documenting to other police officers as a public risk. This contrasts with the experiences of Black Nova Scotians. Analysis of street check data from the Halifax Street Check Report indicates that officers will often add supplementary notes that identify Black citizens as anti-police, aggressive, and potentially dangerous.Footnote 77 Everything in the interaction between the RCMP officer and the perpetrator suggests that he should have been identified as aggressive, and thus potentially dangerous, but, instead, formal documentation would have others believe that the perpetrator was an apologetic citizen when caught speeding on a rural Nova Scotian road.

Figure 2. Speeding Ticket Involving the Perpetrator, 12 February 2020.

Researchers argue that racial bias can lead to improper investigations, as an officer who is influenced by their biases can overlook situations that may lead to potential dangers. In other words, a focus on certain groups of people may result in an officer’s letting their guard down around other individuals who are in fact dangerous.Footnote 78 The documented incidents between the perpetrator and the police may demonstrate how an intersection of class, gender, and racial bias led to a dangerous underestimation of the threat posed by the perpetrator.

Conclusion

The documented interactions involving the perpetrator and the police may be easily dismissed and believed not to prove in general that Whiteness and socioeconomic status protect one from police surveillance. However, it is difficult to ignore the disparate treatment in comparison with the stories, experiences, and documented data demonstrating that Black, Indigenous, and racialized people are viewed with increased suspicion and are therefore subject to increased police surveillance and documentation. The reverse—and what this case study demonstrates—is how White people may instead be given the benefit of the doubt as resources and attention are disproportionately allocated away from investigating White suspects, especially if they do not fit the stereotypical profile of a criminal. This results in more rigorous scrutiny for racialized and lower socioeconomic people while neglecting potentially dangerous individuals such as the perpetrator.

Some may argue that the two reviewed incidents involving the police and the perpetrator are coincidental and do not demonstrate differential treatment based on these biases. However, when considering race, the research in Canada on police stops and racial profiling consistently demonstrates that Black, Indigenous, and other racialized people are much more likely to be subjected to involuntary police contact, and subsequently documented within the police system, than their White counterparts. Furthermore, how can one explain the perpetrator’s ability to evade any form of accountability let alone criminal liability, when explicitly demonstrating aggressive and intimidating behaviour toward a law-enforcement official, on numerous occasions? While the current analysis reviewed the intersection of class and gender, race is a salient factor. As noted by a Black Nova Scotian, from the Street Check report: “Black people in Nova Scotia have always suffered from inequality and discrimination and the police are a major part of that oppression […] We have always suffered from criminalization, false arrests and brutality. The justice system has not protected us the way it does the White community. The police […] keeps us down and maintains the status quo.”Footnote 79

A young mother expresses a similar sentiment when she states: “Our kids don’t get a second chance with the police like White kids. You mess up once and it is going to impact you for the rest of your life. You’ll get a record and then the police will always track you.”Footnote 80 This sentiment demonstrates the systemic barriers experienced by Black people because of police practices in their communities. If the data suggest that people from Black communities are subject to over-surveillance through stop-and-search tactics, are more likely to experience use of force by the police, and are more likely to be impacted by harsher arrest decisions through the process of formal documentation, then people within these communities are criminalized. The current analysis suggests that White people are protected from similar scrutiny.

When considering additional infamous White Canadian criminals who escaped police attention for long periods of time, including Bruce MacArthur, who was responsible for the murders of both racialized and White gay men; Russel Williams, who murdered and sexually assaulted multiple White women; Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka, also responsible for the murder and sexual assaults of White women; and finally Robert Picton, convicted of murdering Indigenous and White women, the similarities are worth noting. Much like the perpetrator of the mass casualties, these White predators may have escaped police attention for long periods due to the protection that their race may have provided for them. But, without access to previous police interactions involving these individuals, a thorough exploration is not possible.

Could fair police documentation practices of public citizens have alerted the police about the perpetrator’s violent nature sooner, perhaps changing the initial course of the mass casualty investigation? By no means am I advocating for an intrusive police state in which all citizens are forced to provide their personal information and details to be subjected to unnecessary surveillance. I simply aim to highlight that, when the police engage in differential surveillance and documentation practices that target racialized communities, law-enforcement officials not only help to perpetrate long-standing disparities, but also compromise our collective safety.