Introduction

In response to growing concerns about the inconsistencies between bail decisions and criminal law, there have been a number of recent attempts to fix Canada’s “broken bail system” (Webster Reference Webster2015). The courts and government ministers alike have emphasized the need to change the way bail operates in practice to avoid placing accused in situations that make future breaches of bail conditions likely. Most notably, in June 2017, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC), in R v Antic, took a strong position that participants in the justice system must “return to the first principles of bail, as both a matter of law and as a matter of practice” (as described in R v Tunney para 36). Rather than change the law on bail, the R v Antic decision simply reaffirmed the ladder principle, which states that accused must be released on their own recognizance and without conditions unless the Crown can show cause why a more restrictive form of release is necessary. The Superior Court of Ontario in R v Tunney (2018) later reiterated this sentiment, attributing the misapplication of the law to a departure from the spirit of bail as outlined in the Criminal Code. According to both decisions, improving the bail system must first start with changing how the lower courts implement the law. In particular, these court decisions insist that Crowns and justicesFootnote 1 must show more restraint when requesting and imposing release conditions.

Despite the Supreme Court’s judgment that the “least onerous conditions” be imposed (R v Antic 2017), the impact of this high-level call to “follow the law” is, at best, unclear. Whether it has had any meaningful impact on the way bail conditions are imposed in the lower courts, where most bail matters are heard, is uncertain. After all, Supreme Court decisions are only as effective as the way they are interpreted and applied in practice (Gorman Reference Gorman2017; Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999; Johnson Reference Johnson1987).Footnote 2 Thus, understanding how Supreme and Superior court decisions shape the on-the-ground practices of the courtroom workgroup,Footnote 3 which has its own norms and routines, is an important step in assessing the effectiveness of these rulings. As Yule and Schumann (Reference Yule and Schumann2019) find in their study on the in-court negotiation among justices, Crowns, and defence, the use of more restrictive releases and the imposition of numerous conditions result from the blurring of occupational roles and adherence to courtroom norms like efficiency and risk aversion rather than the law per se. While the rulings in both Antic and Tunney have been well received by many bail scholars and community organizations, it has yet to be determined whether these decisions have disrupted the existing habits of the courtroom workgroup.

Drawing on observational data from 480 completed bail hearings that occurred both pre- and post-Antic in southwestern Ontario, this study addresses questions about the extent to which this decision has reduced the punitive aspects of bail releases, namely whether it influenced a greater adherence to the ladder principle, resulting in fewer conditions and fewer surety releases.Footnote 4 Knowing the impact of the Antic ruling on lower court decision-making is critical as prior research has long documented the negative and often “devastating” consequences of the improper application of the law of bail, which include “prolonged time spent in remand custody, loss of jobs, separation from family, onerous conditions imposed, and the overuse of surety bails” (Rogin Reference Rogin2017, 331; see also Pelvin Reference Pelvin2019).

Literature Review

The Law on Bail vs. Bail in Practice

Reasonable bail in Canada is protected by the Canadian Constitution (R v Pearson 1992; Gorman Reference Gorman2017). Specifically, section 11(e) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) indicates that “any person charged with an offence has the right…not to be denied reasonable bail without just cause.” This constitutional requirement is intended to safeguard individuals against being unreasonably detained and/or released on bail with overly restrictive terms. Section 515(10) of the Criminal Code of Canada sets out that bail can only be denied to (1) ensure the accused will appear in court; (2) protect the safety of the public, witnesses, or victims and/or prevent the accused from committing an offence; or (3) maintain the public’s confidence in the administration of justice (Criminal Code, 515(10)(a) to (c)). When determining whether, and with what conditions, accused can be released back into the community pending their trial, the legislative framework of bail directs justices to use the ladder principle to ensure the fewest and least onerous conditions necessary are imposed (Criminal Code, s 515). The lowest rung of the ladder indicates that accused should be released on an undertaking (i.e., without conditions and on their own recognizance). If the Crown feels this is inappropriate, they can argue for a more restrictive release, which might include release with a surety or release with conditions that range from reporting to a police officer to house arrest or medical treatment/ programming (Trotter Reference Trotter2010). According to the Criminal Code, a move up the ladder to more restrictive releases must be related to the mandate of bail and should be accompanied by a clear justification from the Crown about why a lesser form of release is inappropriate (Trotter Reference Trotter2010). This approach is intended to prohibit justices from imposing a more onerous form of release unless the Crown shows why it is necessary given the allegations, prior criminal record, history of failure to appear or failure to comply, flight risk, inadequate bail plan, etc.

Despite the written law on bail, pre-Antic scholarship questions whether current trends in bail, such as the overuse of conditions and surety releases, interfere with an accused person’s right to reasonable bail and presumptions of innocence (Canadian Civil Liberties Association [CCLA] 2014; McLellan Reference McLellan2009; Myers Reference Myers2009). Indeed, provincial statistics showing that 70 percent of inmates in provincial custody are in remand are indicative of problems beginning at the bail stage (Malakieh Reference Malakieh2018). Many accused have difficulties meeting the demands of the Crown, who often require a surety and ask that numerous conditions be met before they agree to release, which results in adjournments and time spent in custody (Taddese Reference Taddese2014; Wyant Reference Wyant2016). More than half of those who are able to satisfy the court and are granted bail are released with a surety and are required to abide by restrictive conditions like house arrest, counselling/treatment, or abstinence from drugs/alcohol (Myers Reference Myers2009). While conditions are sometimes necessary to minimize the risk posed by the accused based on the criminal charges, these conditions are often imposed without a strong rational connection to the mandate of bail (Myers and Dhillon Reference Myers and Dhillon2013; Sprott and Myers Reference Sprott and Myers2011). The increasing use of release conditions in Ontario has the potential to make compliance more difficult and can increase the likelihood of bail breaches (CCLA 2014). The emerging consensus among the comparatively small body of research on bail in Canada is that justices and Crowns have moved away from the legislative framework of bail (CCLA 2014; Lauzon Reference Lauzon2016; Makin Reference Makin2012; Myers Reference Myers2016; Webster, Doob, and Myers Reference Webster, Doob and Myers2009). Accused persons who breach their bail risk being charged with additional offences.

The “Post-Antic World”: Trends in Bail

Many of the problems identified by scholars, legal practitioners, and advocacy groups about onerous bail releases were addressed in the June 2017 Supreme Court decision in R v Antic. After being denied bail and having two failed bail reviews, a third bail review judge granted Kevin Antic bail as long as he had a surety and made a $100,000 cash deposit. In R v Antic, the Supreme Court unanimously agreed that the bail review judge erred by failing to adhere to the ladder principle and refusing to consider forms of release under section 515(2) of the Criminal Code less onerous than a cash deposit and surety. Rather than change the written law on bail, the decision in R v Antic acts as a stern reminder that legal practitioners should adhere more strictly to the ladder principle, where the starting point must be release without conditions (Pan Reference Pan2017).

In late October of the same year, the Ministry of the Attorney General (Ontario) released a new Crown Prosecution Manual that “set out with clarity Ontario’s renewed approach to bail in the post-Antic world” (Minister Naqvi as cited in Robinson Reference Robinson2017). This bail directive urged Crowns to consider the least restrictive form of release and not request a surety until other less onerous options had been rejected as inappropriate. Any conditions requested by the Crown should: 1) “be rationally connected to one of the three grounds for detention in custody”; 2) “relate to the specific circumstances of the accused and the offence”; 3) “be realistic (the accused will be able to comply with the conditions)”; and 4) “be minimally intrusive and proportionate to any risk” (Ministry of the Attorney General 2017a). This means that conditions must be case specific and minimally applied. For example, a “no alcohol” condition should only be requested if there is a connection between “the bail conditions proposed and the circumstances of the alleged offence and the accused” (Ministry of the Attorney General 2017a, 83). Where a connection exists, consideration must be given to crafting the least restrictive bail conditions that still meet public safety concerns, such as no drinking outside your residence as opposed to a complete ban on alcohol consumption or possession. Similar restraint is recommended when considering the use of community supervision. As with conditions, sureties or bail supervision programsFootnote 5 must only be recommended when it is necessary in order to protect community safety and/or ensure the accused attends trial.

Both R v Antic and the Crown Prosecution Manual speak to the principle of restraint when considering bail releases and the importance of upholding the ladder principle. Yet six months after the ruling in R v Antic (2017), Justice Di Luca of the Ontario Superior Court noted in his decision in R v Tunney (2018) that these principles were still being overlooked by both Crowns and justices. According to Justice Di Luca, the requirement that Mr. Tunney needed to have a surety was symptomatic of broader trends, where sureties have become “near automatic” in Ontario, essentially creating a reverse onus scenario in which the accused has to prove why a surety is not required (R v Tunney 2018, para 33). With his decision, Justice Di Luca made clear that Antic was binding law and not merely a suggestion (R v Tunney, para 45).

The succession of events that started with R v Antic respond to a growing criticism that accused are being released with numerous and restrictive conditions that blur the line between prevention and punishment (Myers and Dhillon Reference Myers and Dhillon2013). While the law on bail remains unchanged, decisions in both R v Antic and R v Tunney, as well as the Crown manual, suggest that the problems lie not with the law itself but with how it is applied in practice.Footnote 6 In all three examples, the main objective is to shape the culture surrounding bail decision-making and ensure the roles of the Crown, defence, and justices align more closely with the ladder principle. However, understanding how successful this and subsequent decisions will be in changing bail outcomes must be considered in light of past research on the implementation of higher court rulings on lower court outcomes.

The Aftermath of Supreme Court Decisions

In virtually all instances, higher court judiciary must rely on lower courts to interpret their decisions and translate them into action (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999). By nature, higher court decisions have considerable scope and typically focus on complex and sometimes interrelated circumstances, which can make their application challenging. In addition, higher court decisions can be ambiguous, vague, or poorly articulated such that lower court judges must exercise some discretion in determining what the higher court intends and how it applies to a particular case. Judicial decisions that lack clarity are more likely to produce dissimilar lower court interpretations (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999). Even when a higher court’s decision is clearly written, it is unlikely to answer all questions about its applicability. In the context of bail, for example, R v Antic does not clearly indicate when certain conditions require further justification by the Crown and when they are appropriate to impose using the ladder principle. Not all conditions are experienced equally but it is generally agreed that a curfew represents a more restrictive condition than a no weapons condition. Does this represent a higher rung on the ladder and therefore need additional explanation by the Crown? Generally speaking, the clarity of higher court decisions is problematic if they lack consistent and continuing cues to lower courts about the interpretation of important policies (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999).

Beyond assessing the clarity and scope of higher court decisions, it is also important to recognize how the attitudes of lower-court judges affect the actual implementation of precedent-setting cases like R v Antic (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999). As members of the judicial hierarchy, lower court judges are constrained in interpreting higher court decisions, yet there are also many occasions in which the judge’s own biases enter the decision-making process (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999). While this type of discretion allows judges to adapt to case-specific details, it may result in them accepting a higher court decision enthusiastically, treating it indifferently, or opposing it all together (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999). Johnson’s (Reference Johnson1987) study of lower court reactions to fourteen randomly selected US Supreme Court cases finds that lower courts followed the Supreme Court’s reasoning in a substantial number of cases, especially when there was a high level of similarity between cases.

In dissimilar cases, lower court judges often made decisions that were in keeping with the general spirit of the higher court but exercised more discretion based on the cultural norms of the courtroom workgroup. While overt defiance is unprofessional and a relatively rare event (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999), a lower court judge may ignore a higher court’s decision or rely on another, less appropriate precedent. In other cases, judges might agree with part of a ruling but not all of it. In most cases, lower court judges are keen to follow higher court rulings, at least somewhat, in order to uphold their own reputation and that of the legal system (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999). According to Gibson (Reference Gibson1983, 9), “judges’ decisions are a function of what they prefer to do, tempered by what they think they ought to do, but constrained by what they think is feasible to do.” Indeed, conscientious judges frequently have to make their own best guesses about how to interpret case law and apply it to a particular set of circumstances not considered by a higher court.

When deciding how to apply higher court decisions, judges are further constrained by the dynamics and established court culture in which they work (Flemming, Nardulli, and Eisenstein Reference Flemming, Nardulli and Eisenstein1992; Johnson Reference Johnson1987; Worden Reference Worden1995). The status quo is reflected and deeply embedded in judicial behavioural patterns and decision outcomes. Successful attempts to modify behaviour must become integrated into the norms and values of those who work in the courts. Courtroom participants (i.e., judges, lawyers, clerks) understand their own incentive structures and the adaptive strategies available to deal with legal oversight by the higher courts. In bail court, the justice, Crown, and defence all make up the courtroom workgroup. As members of the courtroom workgroup, these individuals share a “common task environment” (Haynes, Ruback, and Cusick Reference Haynes, Ruback and Cusick2010, 127) of disposing cases and working together to obtain justice and achieve court efficiency (Haynes, Ruback, and Cusick Reference Haynes, Ruback and Cusick2010; Flemming, Nardulli, and Eisenstein Reference Flemming, Nardulli and Eisenstein1992; Eisenstein and Jacob Reference Eisenstein and Jacob1977). Thus, if a higher court decision does not jive with how the lower courts have been operating, they may ignore precedents, especially if appeals are rare (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999). For example, justices may be less inclined to use precedent because they know bail reviews are uncommon (Campbell Reference Campbell2015). Indeed, Justice Di Luca implied that this “inherent comfort” in tradition likely resulted in the continued use of sureties even after the R v Antic decision (R v Tunney 2018, para 57). R v Antic (2017) sends a clear message that “we need to do things differently” to change “our bail culture” (R v Tunney 2018, para 57).

Current Study

The current study adds to ongoing discussions about bail by asking: To what extent do post-Antic bail-related reforms and decisions (including the Ontario Crown Policy Manual and R v Tunney) shape bail outcomes associated with: 1) types of release; 2) number of conditions; and 3) types of conditions? Based on past studies on the implementation of higher court decisions and court culture, we anticipate one of two possible outcomes. First, more accused may be released on their own recognizance and may receive fewer and less restrictive release conditions in bail hearings that occur post-Antic because the members of the courtroom workgroup will understand and follow the instruction from the Supreme Court with respect to adhering to the ladder principle when determining conditional releases. Second, members of the courtroom workgroup will not modify their established norms and practices for deciding upon appropriate bail conditions. As a result, accused may not receive different release conditions post-Antic.

Data and Methods

Data Collection

The analyses are based on data collected from 480 observations of adult bail hearings in which the accused was granted bail.Footnote 7 Of the 480 cases, 258 occurred pre-Antic and 222 post-Antic. Data were collected starting in the year prior to the R v Antic decision until roughly a year post-Antic (August 2018) at three provincial courthouses located in different cities in southern Ontario.Footnote 8 Three different locations were selected to assess whether courts had their own norms and decision-making patterns (Flemming, Nardulli, and Eisenstein Reference Flemming, Nardulli and Eisenstein1992). Specifically, one court was located within the greater Toronto area while the others were located in smaller jurisdictions. Court observations took place one to three full days a week at each location over the course of the study period. A detailed checklist was used to ensure the systematic collection of data for all cases. Modelled on similar studies, the checklist included questions on legal (e.g., criminal history) and extra-legal (e.g., sex, race) factors, defence and Crown submissions, as well as the outcome (i.e., what conditions were imposed by the justice) (Allan et al. Reference Allan, Allan, Giles, Drake and Froyland2005; Engen and Gainey Reference Engen and Gainey2000). It was structured to allow for both closed- and open-ended responses, providing both quantitative and qualitative data for each case. This approach to data collection confers two main advantages on this study: (1) we were able to gather information about the number and type of conditions imposed in each case, and (2) the open-ended portions of the checklist were useful for documenting the justifications offered by defence counsel and Crowns in their submissions to justices regarding which conditions to impose, as well as the justices’ response to these submissions.

Sample

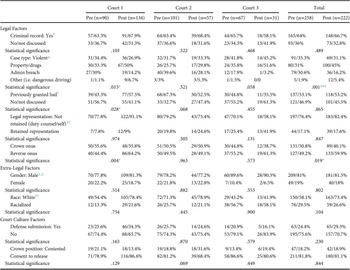

The sample includes accused adult men and women who, after being held by police for a bail hearing, were released with court-ordered conditions. As Table I shows, these accused were, on average, whiteFootnote 9 males who were not represented by a hired defence lawyer at their bail hearing.Footnote 10 The majority of the accused (65%) had a prior criminal record, and roughly half had been on bail previously.Footnote 11 Based on the limited statistics available, the above characteristics appear to be representative of the broader population of accused held for bail, particularly in terms of case severity and legal representation (Ontario Court of Justice 2016; 2017). Table I also shows that the characteristics of accused in the pre- and post-Antic samples are largely similar, though some differences exist. While the accused were primarily charged with a property/drug crime, more cases involved violence or breaches in the pre-Antic sample, while more accused in the post-Antic sample were charged with offences like dangerous driving and had a reverse onus hearing. Compared with our pre-Antic sample, more accused in our post-Antic sample are from Location 1.

Table I Sample Characteristics by Court Location (N = 480)

‡ Criminal Record: 1 missing case

^ Case type: 7 missing cases

† Previous bail: 3 missing cases

‡‡ Legal representation: 17 missing cases

^^ Accused gender: 1 missing case

†† Accused race: percentages do not add to 100% due to the 32 missing cases

* p ≤ .05

*** p ≤ .001

Analytic Strategy

To test the effects of the R v Antic (2017) decision on the type of release as well as the number and type of conditions imposed, all cases that occurred prior to or on June 1, 2017, were coded as “pre-Antic” (0) and all cases that occurred after were coded as “post-Antic” (1). This served as the key independent variable in both the bivariate and multivariate analyses. The bivariate and multivariate analyses test for differences in three outcomes: 1) type of release, 2) number of conditions, and 3) type of condition. Type of release was identified at the time of the hearing and coded into five possible categories based on the ladder principle: 1) undertaking, 2) own-recognizance, 3) surety, 4) cash deposit, and 5) cash deposit and surety. The number of conditions was measured by coding the conditions into twelve possible types or groups and counting them. More specifically, condition types include do not communicate with specific people, obey a boundary restriction, reside at a particular address, participate in a bail supervision program, do not possess (e.g., cell phone, illegal drugs), do not possess/consume alcohol/drugs, obey a curfew, remain under house arrest, attend programming, do not possess weapons, report to (e.g., the police, probation officer), and “other” (e.g., do not operate a motor vehicle). With the exception of communication, boundary, do not possess items, and do not possess/consume alcohol/drugs, each condition was applied only once by the court and subsequently coded as “yes” or “no.” Communication, boundary, do not possess, and do not possess/consume alcohol/drugs, however, were often imposed several times and were thus coded as a continuous variable for our initial bivariate analysis. For example, if an accused received a no-contact order with four people, we coded this as having received four communication conditions as opposed to only one. In later analyses (logistic regressions), we were interested in whether there was an overall reduction in the type of condition and thus coded them as dichotomous variables (i.e., accused were coded as “1” if they received a communication condition, irrespective of the number of communication conditions imposed).

Control variables include measures of the court workgroup dynamic as well as legal and extra-legal variables. The court culture variables, which capture dynamics of the court workgroup, include the court location (courthouse 1, 2, or 3), whether the defence makes a submission (0 = no, 1 = yes), the Crown’s position (0 = consent, 1 = contested), and the number of Crown-recommended conditions. The five legal variables include having a previous criminal record (0 = no, 1 = yes), whether the case is reverse (versus Crown) onus (1 = yes), whether the accused has a bail history (1 = yes), the nature of the alleged offence (violent, property/drugs, administrative or other),Footnote 12 and whether the accused retained (hired) legal representation (1 = yes). Finally, the two extra-legal variables are gender (male = 1) and race (white = 1 vs. non-white = 0).

Bivariate analyses were run to identify preliminary trends in our data (see Table II). Three different multivariate models were then used to examine the impact of R v Antic on bail releases. First, a multinomial regression was used to measure the effect of R v Antic on the type of release (Table III). Second, an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was used to test the difference in number of conditions imposed pre- and post-Antic (Table IV). And third, logistic regression was used to assess the impact of R v Antic on the type of conditions imposed (Tables V.1 to V.3).

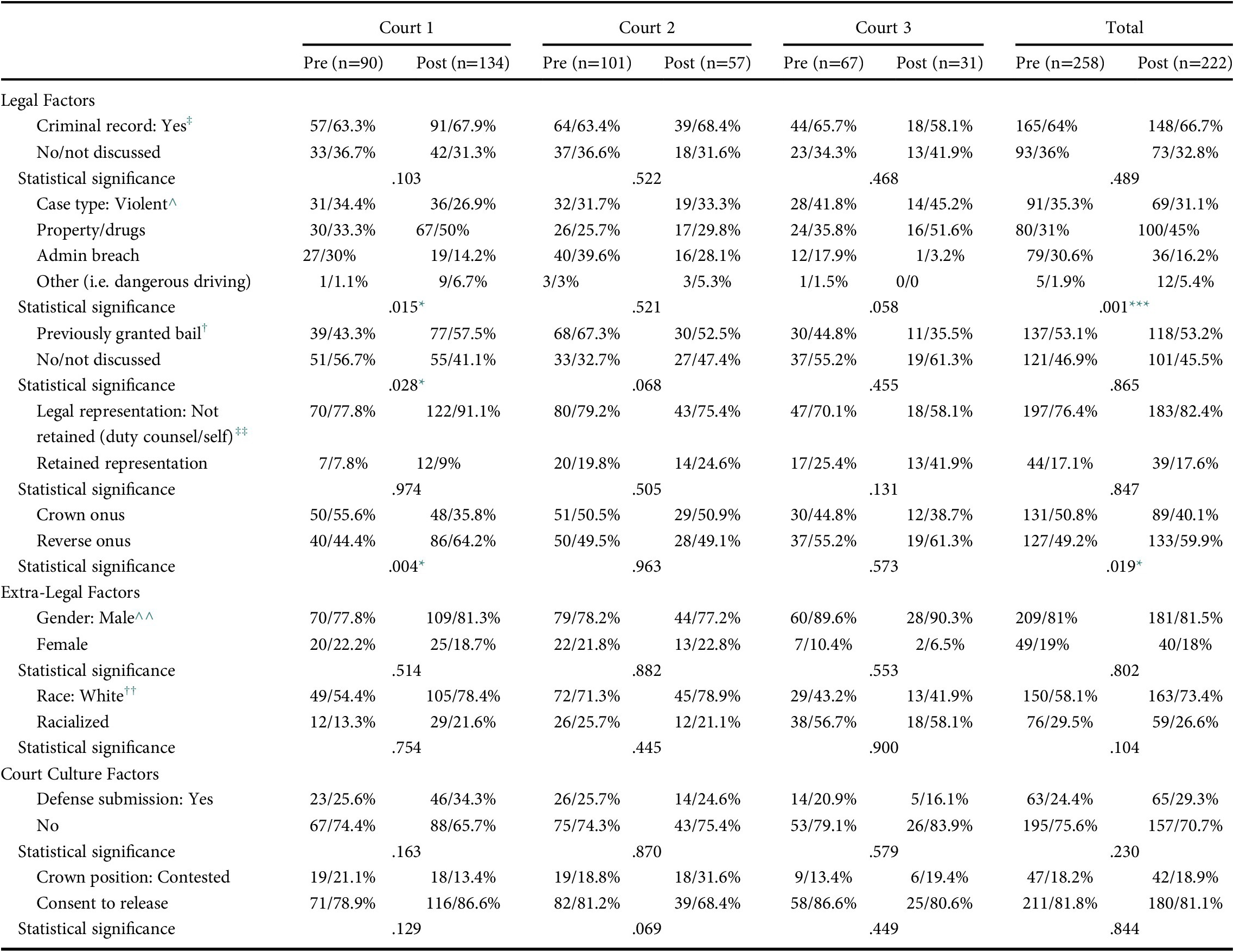

Table II Bi-Variate Comparison of Pre- and Post-Antic Cases by Court Location

* p ≤ .05

** p ≤ .01

*** p ≤ .001

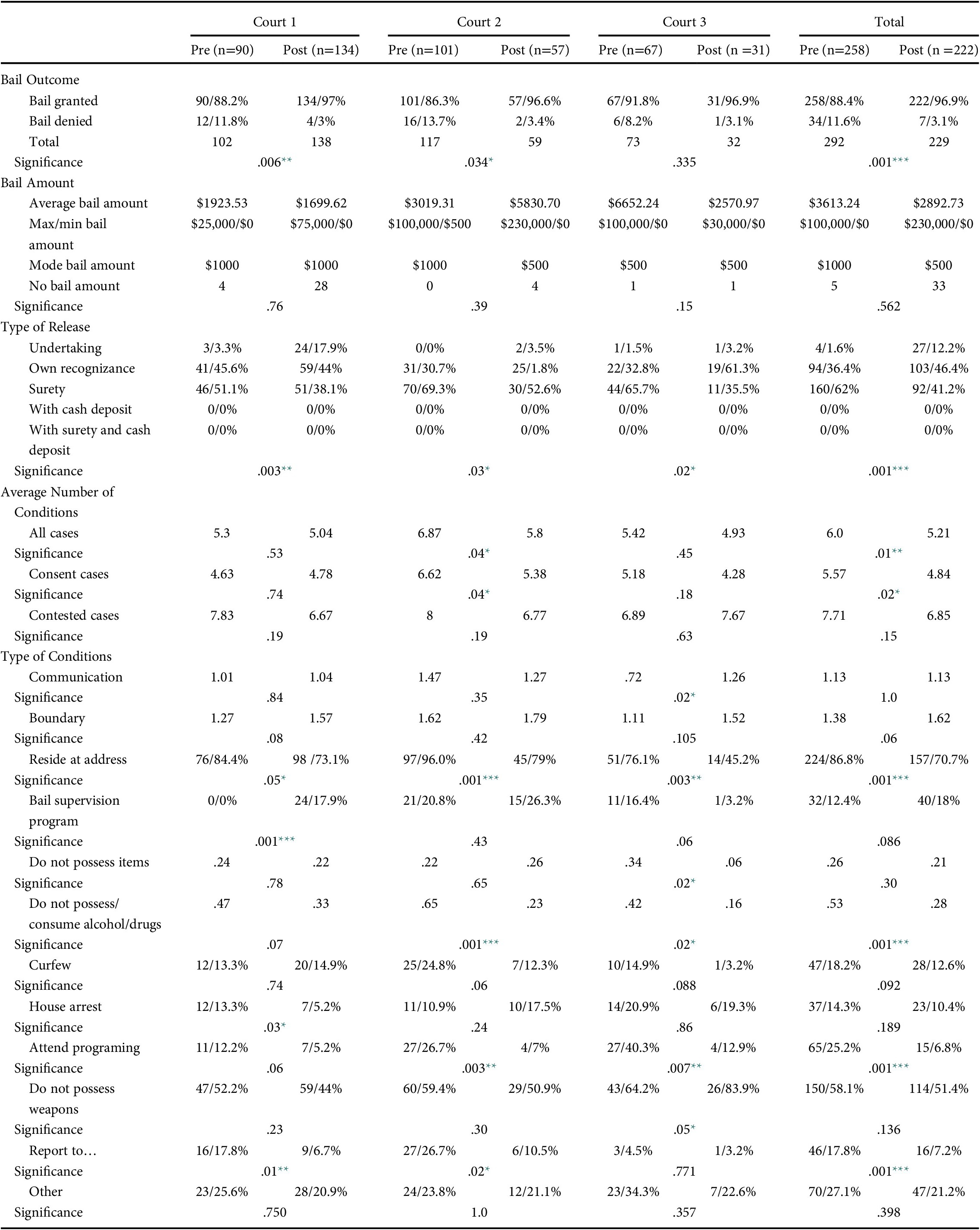

Table III Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting the Effect of Antic on Undertaking and Own Recognizance Compared with Surety Releases (N = 431) †

‡ no Crown contested cases resulted in an undertaking so this factor was deemed redundant.

* p ≤ .05.

*** p ≤ .

† Reference categories are as follows: Surety=1; Pre-Antic=1; Criminal record (1=yes); Reverse onus=1; Previous bail (1=yes); Case type (1=violent); Legal Representation (1=duty counsel/self); Accused gender (1=male); Accused race (1=white); Location (1=Toronto); Defense made submission=1; Crown position (1=consent release).

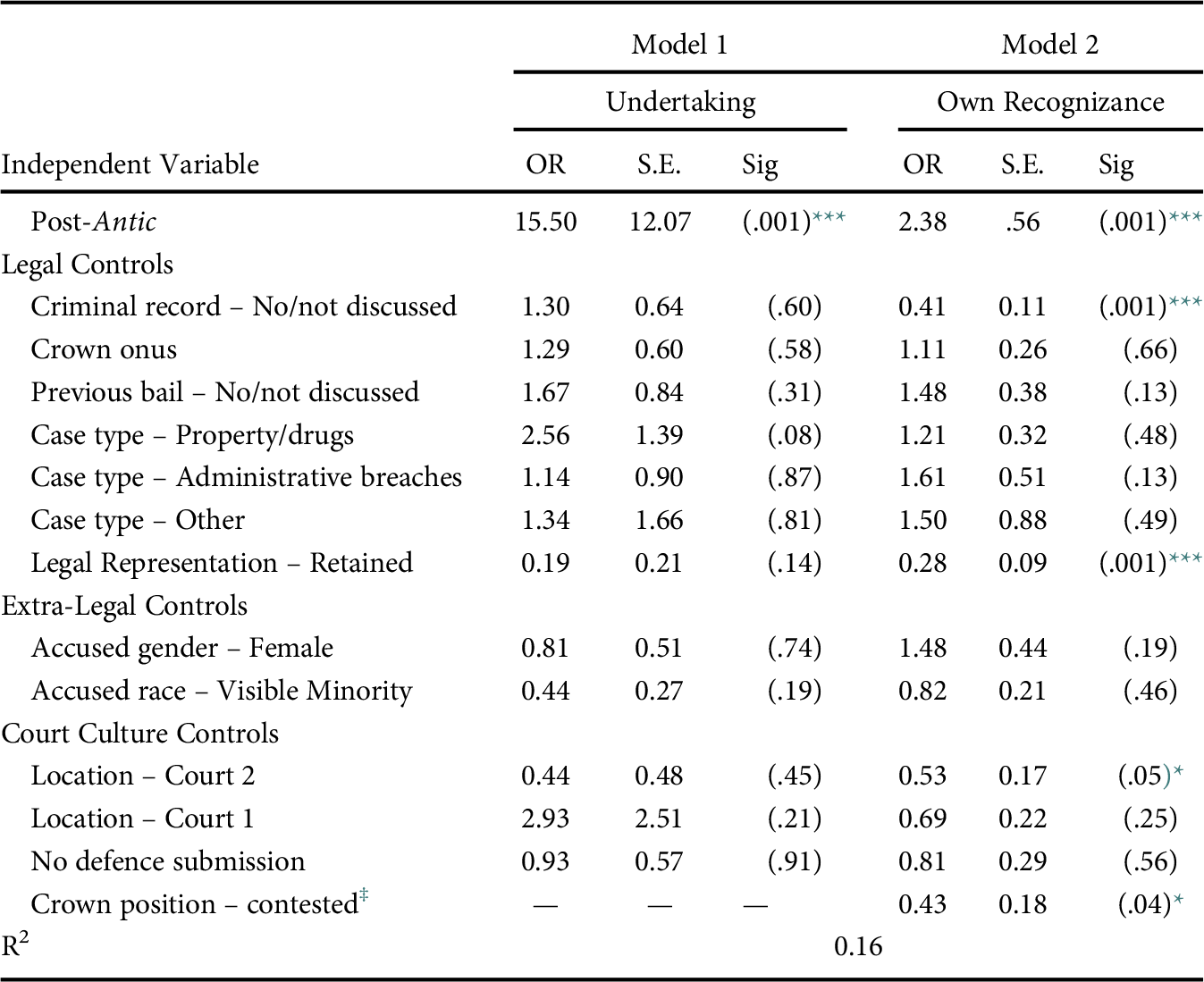

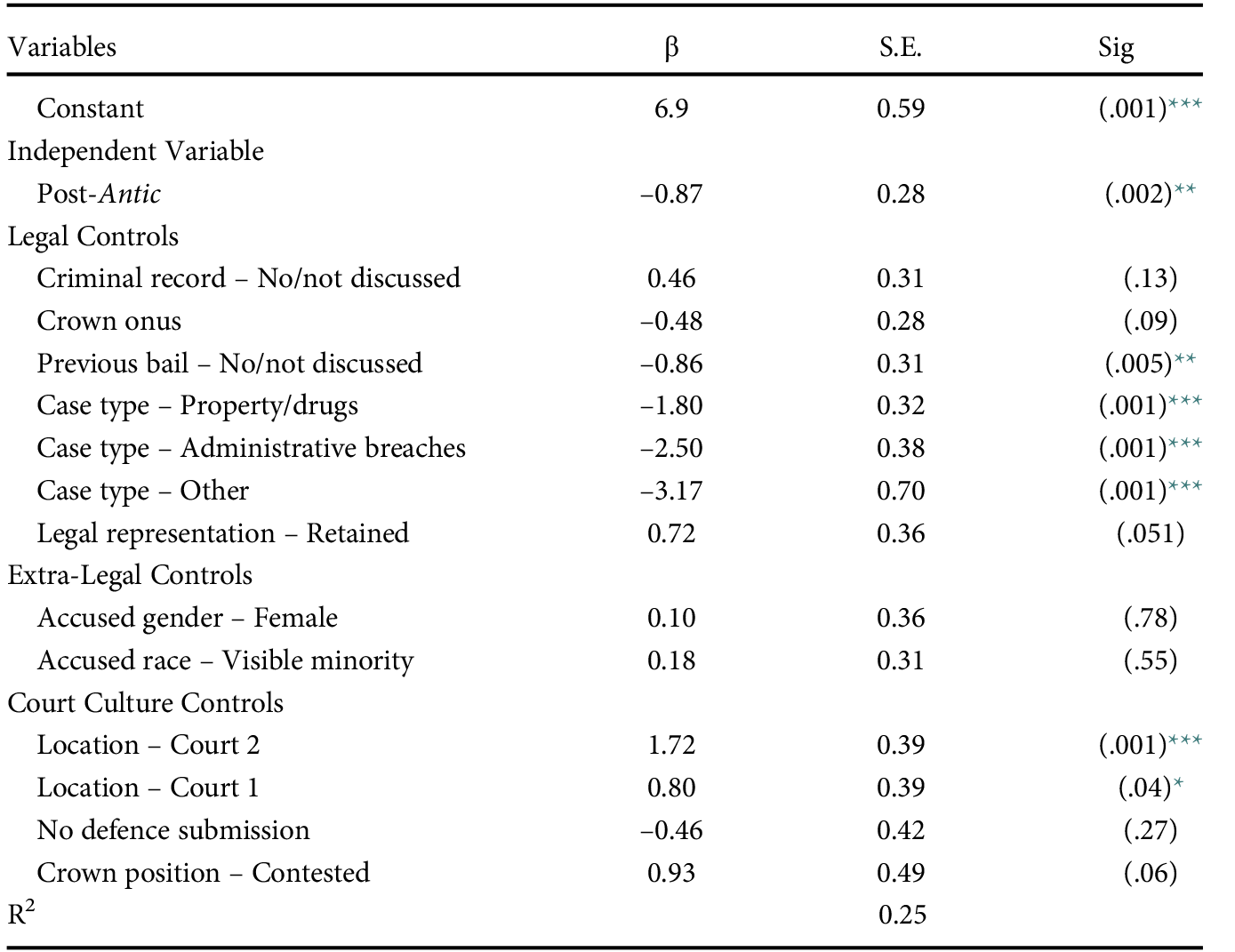

Table IV Ordinary least squares (OLS) Regression Measuring the Effect of Antic on Number of Conditions (N = 426) †

* p ≤ .05

** p ≤ .01

*** p ≤ .001

† Reference categories are as follows: Pre-Antic=1; Criminal record (1=yes); Reverse onus=1; Previous bail (1=yes); Case type (1=violent); Legal representation (1=duty counsel/self); Accused gender (1=male); Accused race (1=white); Location (1=Toronto); Defense made submission=1; Crown position (1=consent release).

Table V.I Logistic Regression Predicting the Effect of Antic on Type of Conditions – Communication, Boundary, Residence, and Bail Supervision †

* p ≤ .05

** p ≤ .01

*** p ≤ .001

† Reference categories are as follows: Criminal record (1=yes); Reverse onus=1; Previous bail (1=yes); Case type (1=violent); Legal representation (1=duty counsel/self); Accused gender (1=male); Accused race (1=white); Location (1=Toronto); Defense made submission=1; Crown position (1=consent release).

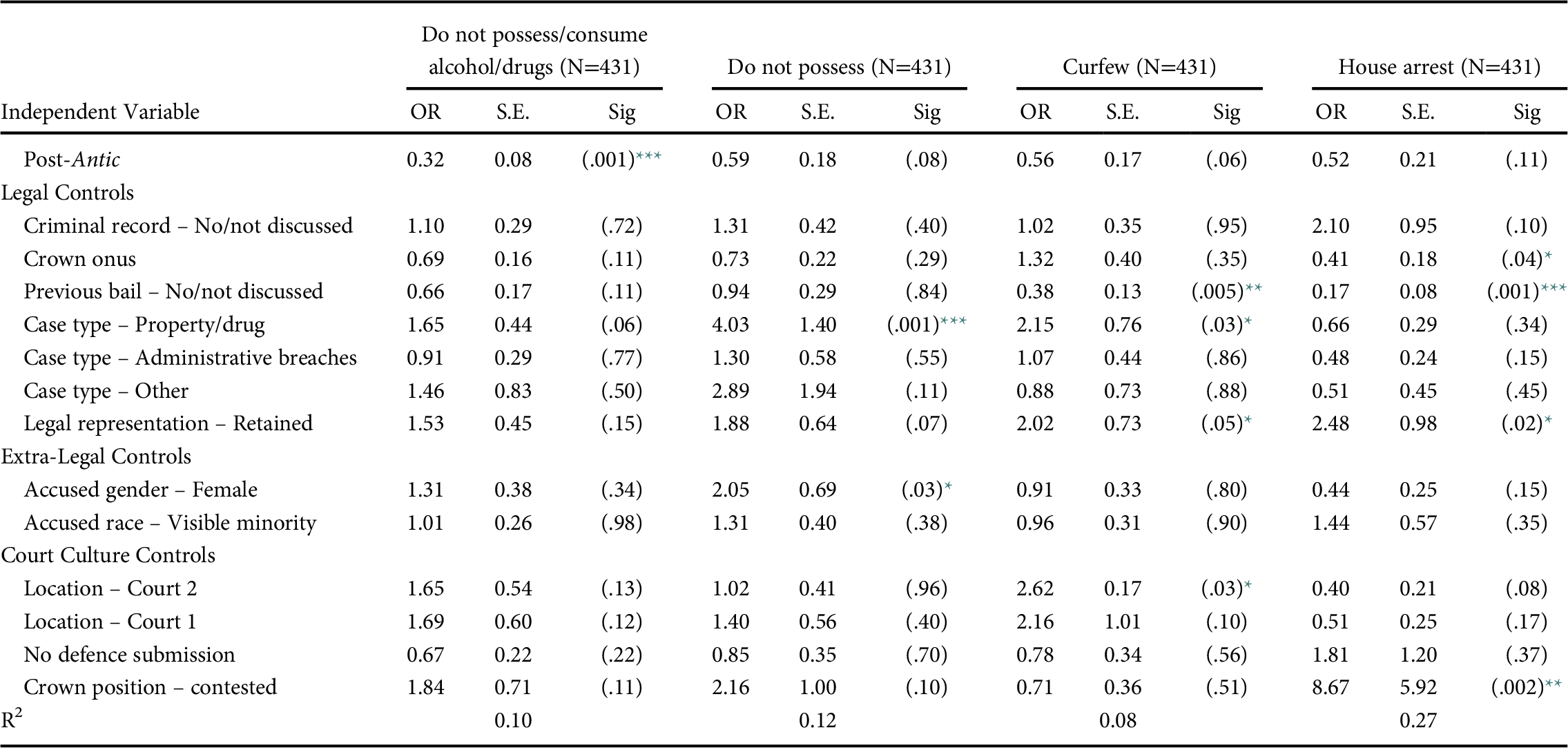

Table V.2 Logistic Regression Predicting the Effect of Antic on Type of Conditions – No drugs/alcohol, Do not possess, Curfew, and House Arrest †

* p ≤ .05

** p ≤ .01

*** p ≤ .001

† Reference categories are as follows: Criminal record (1=yes); Reverse onus=1; Previous bail (1=yes); Case type (1=violent); Legal Representation (1=duty counsel/self); Accused gender (1=male); Accused race (1=white); Location (1=Toronto); Defense made submission=1; Crown position (1=consent release).

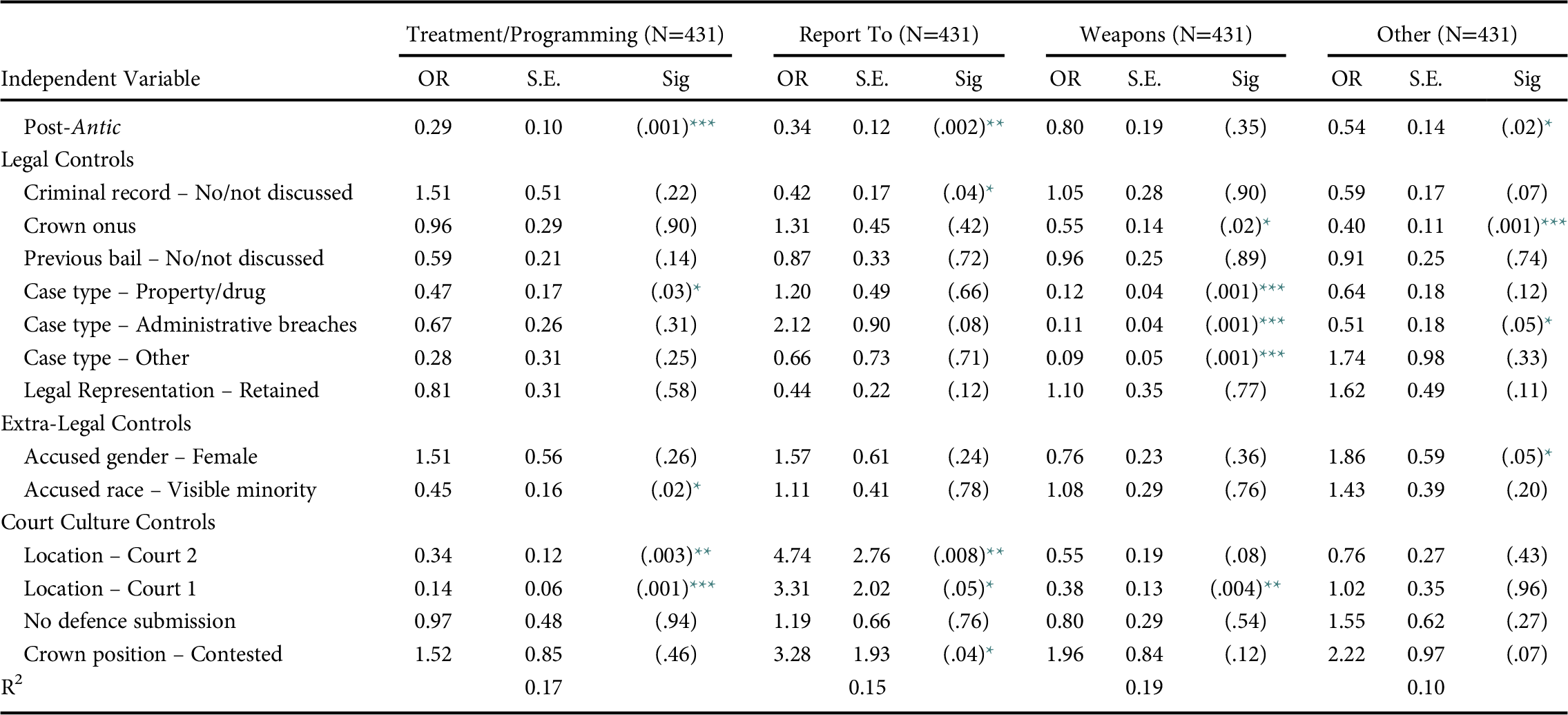

Table V.3 Logistic Regression Predicting the Effect of Antic on Type of Conditions – Treatment, Report to, Weapons, and Other †

† Reference categories are as follows: Criminal record (1=yes); Reverse onus=1; Previous bail (1=yes); Case type (1=violent); Legal representation (1=duty counsel/self); Accused gender (1=male); Accused race (1=white); Location (1=Toronto); Defense made submission=1; Crown position (1=consent release).

* p ≤ .05

** p ≤ .01

*** p ≤ .001

Results

The bivariate results are presented in Table II. This table shows the effect of Antic, by court location, on three main outcomes, namely type of release, average number of conditions and type of conditions, as well as bail outcome and bail amount. The bivariate findings indicate a decline in the number of accused denied bail in the post-Antic period, with two locations showing a statistically significant decrease. While it is beyond the scope of the current study, it may indicate that Antic has influenced restraint not just in imposing conditions but also in denying bail. Compared with release decisions pre-Antic, accused are more likely to be released on an undertaking or on their own recognizance and are less likely to need a surety following Antic. It is important to note that no one in the sample, neither pre- nor post-Antic, was released with a cash deposit or a surety and cash deposit

The court locations responded similarly in their imposition of several conditions following Antic. In all three courts, accused were significantly less likely to receive a residence condition. There were also three conditions that showed a statistically significant decrease in one or more of the court locations whilst trending downward (but not reaching significance) in the other location(s). These include: attend programming, do not possess/consume alcohol/drugs, and report to conditions. There was no significant difference post-Antic in the imposition of curfew, boundary, or “other” conditions (e.g., surrender passport, take medication, do not sit in the front seat of a vehicle) at any court location. Antic did not have a significant effect in two of the three court locations (or overall) for the following conditions: communication, bail supervision, do not possess items, house arrest, and do not possess weapons. Taken together, these results indicate a largely similar pattern in how release decisions are made across all three locations post-Antic. As such, our multivariate analyses are not presented by court location.

Extending the findings of the bivariate analyses, Table III shows the effect of R v Antic on the type of release. The results of Model 1 indicate that, controlling for a host of legal and extra-legal factors as well as court location, accused in the post-Antic period are significantly more likely to receive an undertaking than a surety release compared with accused in the pre-Antic period. The pattern is very strong: the odds that accused in the post-Antic period will receive an undertaking are sixteen times as large than accused in the pre-Antic period. Likewise, Model 2 in Table III shows that the type of release is less restrictive post-Antic. The odds that accused will be released on their own recognizance compared with a surety release is two times as large in the post-Antic period.

While none of the control variables predict whether an accused will receive an undertaking (Model 1), Model 2 shows that some legal and court culture variables shape whether an accused is likely to be released on their own recognizance. Accused are significantly less likely to be released on their own recognizance (versus a surety release) if they have no criminal record (OR = 2.5), have a retained lawyer (OR = 3.33), have a bail hearing in Court 2 (OR = 2), and have a contested hearing (OR = 2.5). The direction of the relationship between not having a criminal record and retaining a private lawyer initially seem counterintuitive. To further interrogate these findings, we ran a cross-tab on charge type by criminal record and found that a large portion of accused without a criminal record (50%) were charged with a violent offence. Based on extensive courtroom observation, we suggest that in these cases, the criminal record or lack thereof is less relevant given the severity of the charge. In other words, the charge warrants a more restrictive (i.e., surety) release, irrespective of the presence or absence of a criminal record. Similarly, 42 percent of those who retained a lawyer were charged with a violent crime. Again, we speculate these accused understand the gravity of the charges against them and seek legal representation, which they perceive will help secure them release on bail.

Consistent with the findings above, Table IV indicates there is a strong and significant effect of R v Antic on the number of conditions imposed. Accused receive significantly fewer conditions post-Antic. Pre-Antic, accused received 7 conditions, on average, upon release. Post-Antic, there is a 0.87 reduction in the number of conditions imposed, meaning accused receive 6.1 conditions, on average. In addition to R v Antic, several legal factors also influence the number of conditions. Accused who have no bail history (β = –0.86) and those who are charged with a property/drug (β = –1.8), administrative (β = –2.5) or other (β = –3.17) offence all receive significantly fewer conditions in the post-Antic period compared with accused who have been on bail in the past and are charged with a violent offence. Accused in court 1 (β = 0.80) and 2 (β = 1.72) received more conditions post-Antic than accused in court 3.

Tables V.1 to V.3 reveal the effect of R v Antic on the types of conditions imposed. Of the twelve condition types examined in the study, five are significantly less likely to be imposed, and one is significantly more likely to be imposed, in the post-Antic period. There are reductions in the imposition of the following conditions: residence (OR = 3.7), do not possess/consume alcohol/drugs (OR = 3.1), attend treatment/programming (OR = 3.5), report to (police, probation, etc.) (OR = 2.9), and ‘other’ conditions (e.g., operate a motor vehicle, access the internet) (OR = 1.9). Conversely, accused are more likely to be required to report to a bail supervision program (OR = 1.9). There were no significant differences between the pre- versus post-Antic period in the use of communication, boundary, curfew, house arrest, do not possess items, and weapons conditions.

Among our control variables, location, charge type, and Crown position are the most common predictors of a variety of conditions. With respect to location, we see a trend whereby Location 3 is less likely to impose communication, boundary, residence, curfew, and report to conditions than Location 1 and Location 2, but more likely to impose a programming condition. Compared with those charged with a violent offence, accused who are charged with property/drug, administrative and “other” crimes are less likely to receive communication (OR = 14.4/9.9/22.2), boundary (OR = 8.1/10.6/28.9), programming (OR = 2.2, property/drug only), and weapons (OR = 8.1/9.1/11.7) conditions and more likely to receive do not possess items (OR = 4.0, property/drug only) and curfew conditions (OR = 2.2, property/drug only). In cases where the Crown contests release, accused are more likely to receive a house arrest (OR = 8.7) and report to condition (OR = 3.3), but are less likely to get a bail supervision program (OR = 2.9). Also notable, extra-legal factors including gender and race had minimal effects on the types of conditions imposed (see Tables V.1 to V.3 for more details about the control variables).

Taken together, our results show the principle of restraint emphasized in the R v Antic decision has changed the way bail is practised in Ontario.

Discussion and Conclusions

Prior to R v Antic, bail in Ontario was characterized by numerous conditions and surety releases that eroded presumptions of innocence and the right to reasonable bail (Myers Reference Myers2016; Webster, Doob, and Myers Reference Webster, Doob and Myers2009; Sprott and Myers Reference Sprott and Myers2011; Myers and Dhillon Reference Myers and Dhillon2013). The shift away from the ladder principle and the legal mandate of bail created a revolving door whereby accused were oftentimes released only to be returned to custody for breaching their conditions. Against the backdrop of increasing failure to comply offences (Burczycka and Munch Reference Burczycka and Munch2015) and remand rates (Reitano Reference Reitano2017), the Supreme Court decision in R v Antic acted as a reminder that Crowns must show restraint in recommending conditions and justices must similarly show restraint when imposing conditions (Pan Reference Pan2017; Raymer Reference Raymer2017). By reinforcing existing criminal court procedures outlined in Sec 515(10) of the Criminal Code, the decision aimed to make bail more consistent and fairer. The current study documents how the landscape of bail in Ontario has changed since R v Antic.

A comparative analysis of bail releases in the pre- and post- Antic period reveals important differences in the aftermath of R v Antic with respect to: 1) the types of bail releases used; 2) the number of conditions required; and 3) the types of conditions imposed. In keeping with the ladder principle, our results show that accused are significantly more likely to be released on an undertaking or on their own recognizance than with a surety following this Supreme Court decision. The strength of the Antic decision in predicting release undertakings indicates the centrality of the court decision for fostering more restraint when determining bail outcomes than what existed pre-Antic. Yet while this finding is important to the extent it demonstrates that the types of releases accused are given are seemingly less onerous post-Antic, it does not provide conclusive evidence of a widespread cultural shift away from overly restrictive conditions among members of the courtroom workgroup. Knowing the effect of Antic on the number and types of conditions imposed is also crucial, as both have been attributed to increases in bail breaches (CCLA 2014; Hannah-Moffat and O’Malley Reference Hannah-Moffat and O’Malley2007; Moore and Lyons Reference Moore, Lyons, Hannah-Moffat and O’Malley2007).

Following the R v Antic decision, accused receive approximately one fewer condition, on average, than in the pre-Antic period. Although a reduction of only one condition may not appear to be a sizable change, it is both statistically and substantively significant. Despite the dearth of research on the lived experience of bail, anecdotal evidence suggests that having even one fewer condition to follow can minimize the overall impact conditions have on the day-to-day lives of accused on bail (CCLA 2014; JHSO 2013). This is particularly true for some types of conditions, such as drug and alcohol abstinence and treatment clauses, which can make compliance challenging. Requiring accused to modify their behaviour by abstaining from drugs/alcohol or attending treatment risks further criminalizing those with addictions or mental health issues (CCLA 2014). The volume of research documenting the problems caused by these types of conditions and the threat they pose to certain constitutional rights further underscores the importance of our finding that there is a statistically significant decline in not only the overall number of conditions imposed but also the use of conditions that modify behaviour post-Antic.

Conditions requiring accused to attend programming and abstain from drug and alcohol use are imposed less often in the post-Antic period. In rare cases, justices in our study went so far as to ask accused if they thought they would be able to abide by an abstinence clause before imposing one. This represents a marked departure from the frequency with which abstinence and treatment conditions were imposed in the pre-Antic era (for reference see CCLA 2014). The significant reduction in the number and type of conditions post-Antic is noteworthy given that accused persons who breach their bail risk being charged with additional offences, even if they are criminally discharged or found not guilty of the original charge (Sprott and Myers Reference Sprott and Myers2011; Webster, Doob, and Myers Reference Webster, Doob and Myers2009). Thus, imposing fewer and less restrictive conditions may reduce “revolving door” justice as well as uphold constitutional safeguards against unreasonable bail.

While very little of the extant research on bail in Canada has focused specifically on smaller jurisdictions, our findings reveal the role of court location in bail decision-making. The similarities noted across court location indicate that there is considerable uniformity in how the R v Antic decision is both interpreted and applied. This finding suggests that the Supreme Court decision is a predominant driving force in accounting for the differences in how bail is being practised pre- versus post-2017. Similar to past studies that document disparities in the use of sureties at provincial and national levels (see Wyant Reference Wyant2016), however, some variation in the application of conditions also emerges in our study. These differences may be a function of local court norms that influence exactly how members of the courtroom workgroup interpret and apply higher court decisions (Gibson Reference Gibson1983). Interviews with members of the courtroom workgroup would be an important next step in this regard in trying to better understand why conditions like communication and do not possess items would be imposed differently across three different courts.

Our findings offer insight into the implementation of higher court decisions in lower courts. As previously discussed, research on judicial decision-making establishes that lower courts implement higher court decisions along a spectrum—from virtual ignorance to enthusiastic acceptance—depending on a variety of factors such as the clarity of the decision, local court culture, and external and occupational pressures (Canon and Johnson Reference Canon and Johnson1999). Differences in the use of sureties and conditions in the post-Antic period signal that bail courts are adopting practices that align more closely with the Criminal Code, suggesting that this is a good example of how lower courts may adhere closely to an upper court decision. In forty-four cases (20% of post-Antic cases), either the defence or the justice overtly referred to Antic or the ladder principle to support their position regarding the appropriate release conditions to impose. The defence used Antic as leverage to dispute the imposition of excessive conditions, while justices used it to require that Crowns better justify their submission for onerous conditions. In one case, the justice disagreed with both the Crown’s and defence’s joint request of a surety release because the accused did not have a criminal record. Citing Antic, the justice rejected the proposed surety plan and instead released the accused on his own recognizance. In contrast to pre-Antic trends, whereby the defence and justices rarely strayed away from Crown-recommended conditions due to a blurring of occupational roles (Yule and Schumann Reference Yule and Schumann2019), the current findings indicate that Antic has provided the defence and justices with an additional tool to help counteract the “bargaining” power of Crowns.

We speculate that the successful implementation of Antic in bail courts can be attributed to a combination of factors. While Antic simply reinforced the existing law on bail and therefore was not a ground-breaking decision in and of itself, it came at a time when there was building momentum to change the way bail operated. Bail reform became a priority for both provincial and federal governments in mid-2016 as criticism from legal advocates and scholars grew (CCLA 2014; Brown Reference Brown2016; JHSO 2013; Myers Reference Myers2016; Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs 2017; Webster Reference Webster2015). Smaller-scale changes were already happening in Ontario, for example, with the addition of bail beds and court staff in certain jurisdictions (see Ministry of the Attorney General 2017b). By the time the Supreme Court delivered its decision in Antic, there was overwhelming agreement among scholars, advocacy groups, and even some members of the courtroom workgroup (i.e., defence and justices) that the overuse of surety releases and conditions was problematic (Ireton Reference Ireton2016; Lauzon Reference Lauzon2016). The Antic decision thus supported existing sentiments about bail practices, which has likely enhanced its effectiveness on lower court outcomes.

The Antic decision has also given JPs, who were under scrutiny for their lack of legal training and inability to hold Crowns accountable under the law (Gallant Reference Gallant2016; Robinson Reference Robinson2016; Wyant Reference Wyant2016), an opportunity to show their legal competence by following higher court decisions and applying the law more appropriately. Justices of the Peace may now be adhering more closely to the Criminal Code than in the past to avoid having their decisions appealed or publicly criticized. A limitation of the current study, however, is that while the collection of reform efforts that coalesced within a one-year time span helps to contextualize the environment in which the Antic decision was made, it makes it nearly impossible to isolate Antic’s specific effect on the way bail operates in practice. While this study uses Antic as a temporal focus, it is important not to overstate the effect of Antic or understate the role of Tunney (2018) and revisions to the Crown Policy Manual (Ministry of the Attorney General 2017a) in fostering changes in bail practices. Nevertheless, the Antic decision was first to address the cultural shifts that were needed to reduce an over-reliance on sureties and conditions, providing direction that has certainly facilitated a move away from past tradition, at least in the short-term.

Despite evidence that justices are imposing fewer and less onerous conditions, some caution is warranted regarding whether Antic and related reforms have truly disrupted how conditions are applied. A notable exception to this pattern is the increasing reliance on bail supervision programs post-Antic. Compared with the pre-Antic period, more accused are now being released on their own recognizance but under the control of a bail supervision program, which requires them to meet with a bail supervisor once a week. While bail supervisors provide less supervision than a residential surety release, they have similar authority to impose added conditions (beyond what the court has imposed) as well as the discretion to decide what classifies as a breach. In this way, bail supervision programs undoubtedly provide a level of oversight and control that goes beyond being released “on your own recognizance.” On the one hand, the increased use of bail supervision programs is consistent with Antic because it reduces the court’s reliance on sureties and helps accused get out of custody sooner. On the other hand, the use of these programs dilutes presumptions that accused should be released on their own recognizance unless there are compelling reasons that a more restrictive release is necessary.

Likewise, although sureties are used less frequently post-Antic, the instructions given to them by the court have changed. Anecdotal evidence from our courtroom observations suggests that when accused are released with a surety post-Antic, there is more direction from the Crown or justice about what added conditions sureties should impose. For example, while justices now impose treatment or drug/alcohol conditions less frequently, they are more likely to suggest that sureties implement these rules under the “routine and discipline of the household.” Both the increased use of bail supervision programs and the instructions given to sureties suggests there may be some shifting of responsibility—from justices to bail supervisors and sureties—regarding who imposes conditions post-Antic. Additional research is therefore required to understand how such changes affect the way bail releases are actually experienced by accused.

Another avenue for future research relates to the relatively short follow-up period—about one year—of the current study. Conducting a follow-up study examining whether the short-term effect of Antic has persisted would be worthwhile as it is possible that although the lower courts responded in the immediate aftermath of Antic, this change lacks permanency. Finally, tracking bail hearing adjournments was beyond the scope of the current study, yet they play an important part in understanding how effective Antic and subsequent reforms have been in ensuring bail decision are being made efficiently.

By focusing on bail outcomes before and after the Supreme Court’s decision in R v Antic, this study provides a timely analysis of the current functioning of bail in Ontario. The decline in surety releases and the number and type of conditions marks a departure from past trends, suggesting that the Supreme Court’s admonition to members of the courtroom workgroup in R v Antic to adhere to the ladder principle has achieved its desired outcome in the short term. While there is some evidence that Antic and subsequent reforms have not sparked a complete break from prior traditions, members of the courtroom workgroup do appear to be using considerably more restraint when crafting release plans. The results therefore have important implications for how accused experience life on bail and the effects of revolving door justice. Crafting release plans that align with the ladder principle protects constitutional rights like presumption of innocence and reasonable bail and provides an additional safeguard against unreasonable Crown demands.