I. Trans Rights: Widening the Lens

There has been great public and legal attention to the role of human rights in addressing trans marginalization.Footnote 1 This article widens the lens on trans rights by turning its attention to trans legal advocacy outside of human rights law. Canadian trans jurisprudence demonstrates that many other legal instruments are involved when trans people engage with the law for recognition, aid, or protection. To those seeking an intersectional approach to trans rights and trans justice beyond the limits of formal equality,Footnote 2 this article asserts that a key starting point is the study of trans jurisprudence.Footnote 3 Case law about trans people helps reveal the sites where trans people intersect with the legal system not only because they are trans, but also because of the ways that the law excludes and perpetuates systemic violence against marginalized people.Footnote 4 Looking beyond human rights legislation and the Canadian Charter,Footnote 5 and towards trans people’s interactions with the law more broadly, allows us to move beyond the narrow frameworks of human rights to better advocate for marginalized trans peoples’ legal needs.

This article joins efforts to move forward conversations about trans rights, which often focus on the promises or failures of equality rights and human rights instruments, into concrete discussions about legal strategies for trans justice. Marginalized people have long grappled with the tensions between equality rights and their limited effect on material realities. This article draws from the work of critical race theory, feminist legal studies, and trans and queer legal studies in articulating a broader legal advocacy agenda for trans rights. It focuses on lessons from Canadian trans jurisprudence in three main legal areas outside of human rights decisions: family law, the use of name and gender in court, and access to social benefits. Trans legal needs in this area are supported by a recent study of legal problems facing trans people in Ontario.Footnote 6 The study identified family law and access to disability benefits as ranking amongst the key legal issues facing trans people.

This article also seeks to centre trans people as legal narrators. By identifying the ways that trans people both intersect with and use the law, we situate trans people as active agents in the legal system. Trans people are not just subjects needing protection from human rights instruments but are also legal actors actively using the law to find ways to protect themselves and improve their lives.

1. Learning from Trans Jurisprudence

The article first addresses the recent focus in Canada on explicit trans human rights protections and the need to look beyond the well-trodden paths of formal equality to respond to trans legal marginalization. The article then employs examples from Canadian trans jurisprudence that illustrate how legal instruments outside of human rights are a key part of a trans advocate’s legal toolkit.

The first cases explored involve trans parents seeking recognition of their relationship to their children or custody and access. These cases show instances of both positive and troubling interpretations of the legal doctrine of the “best interests of the child.” This discussion is followed by cases involving trans minors seeking access to trans healthcare and legal name changes through family law and youth protection law. The article then turns to the use of legal name and gender in the legal system, and the potential harms for trans people whose identity is not respected or who are outed by their interactions with the justice system. Cases involving access to disability benefits are the last examples canvassed, illustrating how the marshalling of evidence can be essential for trans people with disabilities to obtain access to benefits. The article concludes with a call for agile and creative trans legal advocacy to reduce harms to marginalized trans people and respond to the many ways that trans people intersect with the law.

II. Human Rights and Their Limitations

1. Trans Equality Rights

A wave of legal amendments has provided for explicit trans equality rights under Canadian human rights legislation by adding “gender identity,” and in some jurisdictions, “gender expression” as protected grounds.Footnote 7 Prior to adding explicit protections, case law already established that trans people were protected under other human rights grounds, including sex and disability and, in Québec, under the ground of civil status.Footnote 8 Protection under the Québec ground of civil status dates back to 1982,Footnote 9 and under the ground of sex and, if invoked, disability, to 1998.Footnote 10

Kyle Kirkup parses out the history of gender identity and gender expression in Anglo-American discourse,Footnote 11 tracing early calls in Canada for explicit trans protections to a report by lawyer barbara findlay for the Vancouver High Risk Project in 1996. Many scholars and activists went on to advocate for the addition of explicit grounds,Footnote 12 citing the need to decrease trans legal invisibility, educate the public about trans rights, signal inclusion to trans people, and provide a wider scope of protection to trans and gender-diverse people.

In the shadows of trans equality rights movements, backlashes against trans rights have emerged. The rise of anti-trans bathroom bills in the United States is one example.Footnote 13 Another is the torrent of anti-trans harassment that many trans women report experiencing on social media.Footnote 14 In Canada, proposed amendments to the federal Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA) to add “gender identity” and “gender expression” attracted activist attention as well as scrutiny from opponents.Footnote 15 Brenda Cossman tracks the concerns about the federal amendments and the specious nature of the legal claims against them.Footnote 16 The level of concern expressed by opponents about the federal amendments seemed particularly disingenuous, as the federal government was essentially the “outlier” Canadian jurisdiction when it finally added explicit trans human rights protections.Footnote 17 Critics of the federal amendments saw a tension between trans rights and freedom of expression but seemingly ignored that most provinces and territories had already amended their human rights acts to add gender identity (and for some, gender expression), beginning with the Northwest Territories in 2002.Footnote 18

In the face of a strong backlash in Canada against trans human rights protections, even advocates concerned by the overemphasis on trans equality rights spoke out in support of the proposed federal amendments to the CHRA. Dan Irving and Jennifer Evans emphasized that adding explicit trans grounds would represent a “hard won symbolic recognition” of trans people, whose lives are often, as Viviane Namaste emphasizes, “socially erased”.Footnote 19 Similarly, Ido Katri asserted that while anti-discrimination laws do little to address structural inequalities, such as sexism and racism, the amendments to the CHRA serve as a valuable symbolic declaration for trans and gender-variant people.Footnote 20

The debates around the addition of explicit trans grounds were extensive and the subject of significant media attention. As is the nature of public discourse, there was little focus on the fact that the federal human rights act was one of the last jurisdictions in Canada to add explicit trans grounds, or on the limited jurisdictional reach of the federal act. Nor did public discussions focus on the many areas of law affecting trans people that were left untouched by the addition of explicit grounds.

Alongside the amendments to human rights legislation across Canada, a wave of successful human rights challenges and subsequent legislative changes have increased trans people’s access to identity papers.Footnote 21 Most of these challenges were brought forward under existing grounds, including sex, which was recognized as protecting trans people since a 1998 case in Québec,Footnote 22 and not the new explicit grounds.Footnote 23 Nonetheless, these parallel legislative and case law successes show how the climate shifted towards increasing legal recognition of trans people over the last decade.

2. The Limits of Equality Rights for Trans Justice

The recent addition of explicit equality protections under human rights legislation represents a significant development for trans people in Canada. The focus on adding explicit human rights grounds has also narrowed the lens on what constitute trans rights. Equality rights for trans people are not the panacea that they may appear.Footnote 24 Recent advocacy to add explicit human rights grounds risks creating a narrative that trans rights are just about human rights and that trans justice is best achieved through human rights law.

As Brenda Cossman and Ido Katri noted upon the passage of legislation adding explicit trans protections to the CHRA, “the work of real equality has only just begun,”Footnote 25 and human rights are but one instrument to improve trans lives. Social justice movements have taught us that anti-discrimination laws do not fundamentally address the marginalization caused by sexism and racism. We must carry on with the substantive work of trans rights.

Advocates and scholars acknowledge the confines that trans rights discourse imposes on greater projects for social justice. Viviane Namaste takes a stand against the neoliberal construct of transgender rights.Footnote 26 Libby Adler describes how equality rights discourse limits our ability to imagine law reform possibilities.Footnote 27 Dean Spade asserts that the quest for trans equality and recognition fails to challenge the underlying conditions of poverty and criminalization that are created by the states and institutions from which we seek equality rights.Footnote 28 Dan Irving teaches that “[t]rans human rights cannot offer adequate solutions for social justice.”Footnote 29 Florence Ashley urges governments to implement measures that have a broader impact on improving trans lives.Footnote 30

Human rights law reform efforts may divert resources from other pressing legal areas for marginalized trans people, including access to healthcare, the decriminalization of sex work, and the treatment of trans migrants. There are limits to the systemic justice possible from a colonial state that has repeatedly committed social erasure with the very act of registering or refusing to register some people’s existence.Footnote 31 Trans rights are asked of a state that refused to allow trans people to change their identity papers without sterilization, in which the province of Québec still does not allow non-citizens to change their names and sex, that changed the names of Indigenous children in the residential school system,Footnote 32 and in which a government may still refuse to register the name of a child in an Indigenous language.Footnote 33 Engagement in the daily work of trans rights to improve trans people’s life chances must not preclude the work of building alternatives led by those in the state’s margins.

Kimberlé Crenshaw introduces intersectionality to legal theory to demonstrate how the needs of marginalized people who experience intersecting grounds of exclusion are not accounted for when movements only organize around a single issue.Footnote 34 She demonstrates how serving the needs of women of colour seeking support for domestic violence requires responding not only to needs that relate to sexism and poverty but also barriers to accessing housing and employment due to racial discrimination.Footnote 35 Dalia Tourki et al. report that racialized trans youth and migrant trans youth in Québec describe intersecting experiences of exclusions related to their gender identities, citizenship, race, and age.Footnote 36 Dean Spade discusses how law reform strategies shift when intersectional resistance is centred. Instead of seeking out large symbolic victories under equality rights, law reform can be used to strategically reduce harm and improve material circumstances.Footnote 37 Aren Aizura proposes an intersectional approach to trans rights that focuses on the trans people “most vulnerable to violence, death, and discrimination,” and how the law more generally marginalizes sex workers, prisoners, and immigrants without status.Footnote 38

For trans people, living in poverty is often related to the harms of discrimination and exclusion; access to social benefits may be key to material survival. Where the relationship of a single trans parent to their child is not legally recognized, the tools of family law doctrines may offer a recourse. For trans youth rejected by their families of origin who are facing homelessness, an intersectional trans legal toolkit must consider how to provide trans minors with more legal agency over their lives. For migrant trans people, trans justice strategies must directly address immigration law and its intersection with the criminal justice system.Footnote 39

3. Pragmatic and Flexible Trans Legal Advocacy

Widening the lens on trans rights helps an advocate find a pragmatic and flexible approach to trans legal advocacy. This pragmatic approach can still recognize that human rights laws have been fundamental in advancing some trans rights in Canada. Human rights jurisprudence has recognized, for example, that trans people are protected from discrimination in employment and services,Footnote 40 should not be required to undergo surgeries to obtain changes to the gender on their identity papers,Footnote 41 and have the right to request treatment from police and corrections officers that respects their gender identity.Footnote 42

To look outside of human rights does not dismiss the potential role of human rights-based litigation or law reform to address certain trans legal issues. Family law reform, for example, may ultimately respond to human rights complaints about the obstacles to legal recognition of some trans people’s family relationships. Legal doctrines such as “best interests of the child” are to be interpreted with Charter values in mind.Footnote 43 Privacy law is more likely to treat the legal name of a trans person as personal and protected information due to human rights protections for trans people. We can accept that human rights laws may be a useful tool to improve some trans people’s lives, but also recognize the limitations of rights discourses and that trans law reforms often leave behind people on the margins of legal change. Strategic use of human rights instruments can include ensuring that multiple grounds are invoked where discrimination is not sourced to a single axis.Footnote 44 Where discrimination on the basis of gender identity and gender expression are claimed, sex should also be claimed to continue to protect trans people and gender diversity under that human rights ground.Footnote 45

Advocates must also consider the limits of human rights law in the face of the ebb and flow of political battles about the use of the Charter and the protection of minority rights.Footnote 46 The Québec government’s ban on public employees wearing religious symbols invokes the notwithstanding clause to insulate it from Charter challenges.Footnote 47 While the Charter and human rights legislation have become the go-to instrument for protecting minority rights in Canada, Leonid Sirota and Robert Leckey remind us that there are other legal mechanisms for addressing unjust laws.Footnote 48 Just as the principle of the rule of law was recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada as protecting Frank Roncarelli from abuse of power by Premier Duplessis over twenty years before the introduction of the Charter,Footnote 49 so too must advocates be prepared for creative uses of the law to find legal protection and recognition where human rights law cannot or will not go. Minority rights protections under the Charter and human rights instruments may always face the threat of notwithstanding clauses or human rights exemptions.Footnote 50 Trans advocates are wise to broaden their legal strategies.

III. Centring Trans Legal Needs

The cases described below occur in sites of law in which explicit protections under human rights law may not offer an immediate remedy. Instead, the legal tools for advancing trans rights are found in other legal instruments, such as the interpretation of the “best interests of the child” in family law, the wide jurisdiction of the court to make orders under youth protection, the discretion of the judiciary to address trans people by their chosen name and gender, and whether access to disability benefits accounts for the mental health impact on trans people of social stigma and prejudice. Telling some of trans people’s legal stories also helps render visible the trans legal subject, which, albeit constituted within the narrative constraints of the legal system, brings us closer to centring trans people as legal actors.

The problem with learning about trans needs from trans jurisprudence, however, is that the case law leaves out the many trans people who cannot access the legal system. Dean Spade emphasizes that few trans people can afford lawyers, and so few trans people ever get their day in court to address a claim.Footnote 51 A recent study of trans legal needs in Ontario, TRANSforming Justice, states that 71% of respondents reported having at least one legal problem in the last three years, with 69% of those respondents reporting that they needed legal assistance for this issue.Footnote 52 Despite this high number, only 7% reported actually accessing professional legal assistance.

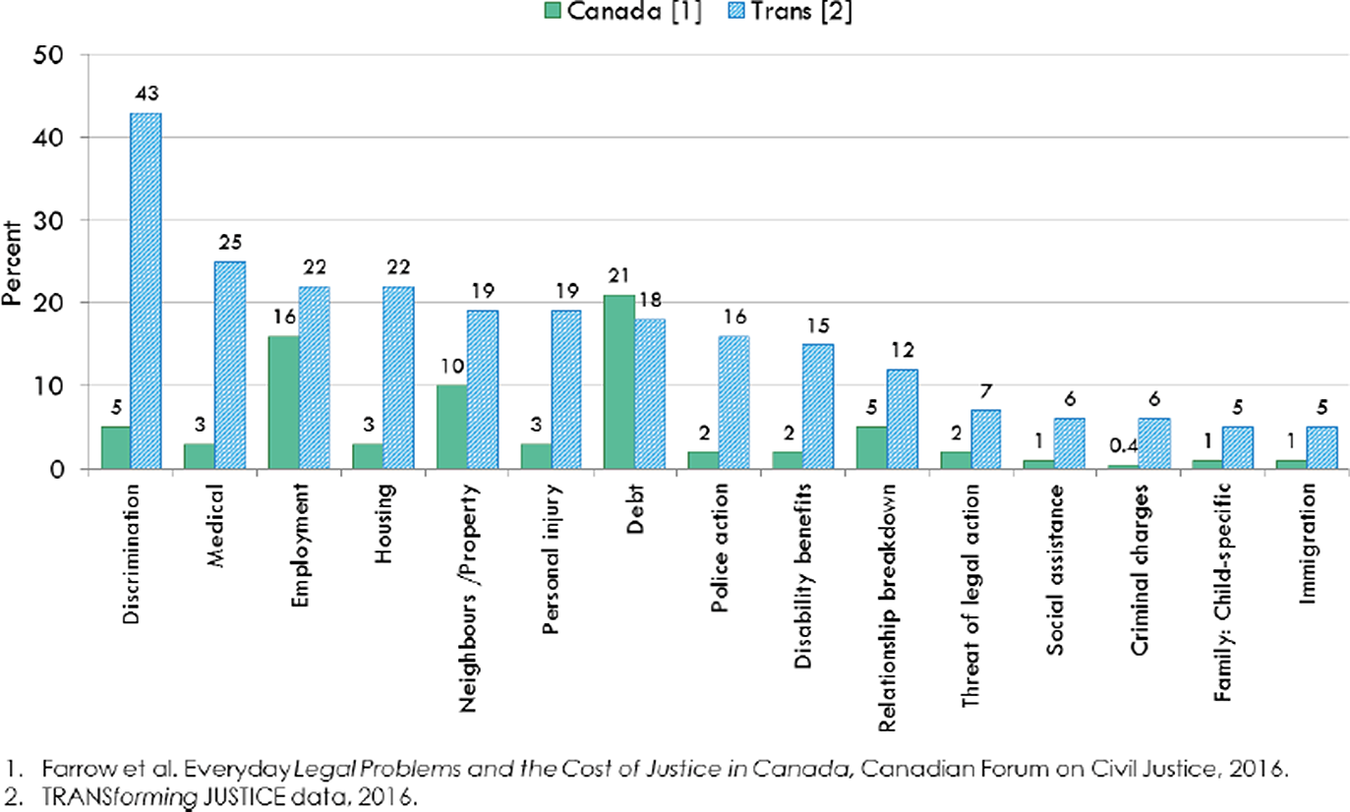

TRANSforming Justice compared trans people’s legal needs with those of the general population. The study demonstrated that trans people’s legal needs are significantly higher than the Canadian population in many legal areas, and that those legal needs may not be directly related to or immediately resolved by human rights law. Trans people report more legal needs than the general Canadian population in areas including family law, criminal law, threats of legal action, and disability benefits, as outlined by TRANSforming Justice in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Legal needs in the past three years: Transgender people in Ontario (n=182) in comparison with Canadian population data. Source: J. James et al., “Legal problems facing trans people in Ontario,” TRANSforming JUSTICE Summary Report 1, no. 1 (September 6, 2018), TRANSforming Justice, https://www.halco.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/TransForming-Justice-Report-One-2018Sept-EN-updated-May-6-20201.pdf at 8.

Clearly, there are limitations to what trans jurisprudence alone can teach advocates about trans legal tools. For a truer accounting of trans legal needs, we must look at trans people’s reports of their experiences with the law. TRANSforming Justice helps articulate the needs of trans people left out of trans jurisprudence, including the many trans people who cannot access legal counsel and are not in a position to self-represent. The jurisprudence discussed below reflects some of the legal areas outside of human rights law that trans people identified as key legal needs, including family law and access to disability benefits.

IV. Trans Parents in Family Law

Family law is a significant source of trans case law in Canada. Early jurisprudence focused on the appropriate legal treatment of a trans spouse and the protection of the institution of heterosexual marriage from the perceived threat of same-sex marriage.Footnote 53 More recent family law jurisprudence addressing trans people is planted firmly in family law concepts like parental capacity, the best interests of the child,Footnote 54 and lawful custody.Footnote 55

Concerns about trans people’s parental capacity appear in Canadian case law in the 1990s, with the courts ultimately establishing that a person’s trans identity in and of itself should not influence determinations of custody and access.Footnote 56 Despite such developments, trans parents report difficulties navigating family law relating to their trans identities, including how custody and access is allocated, as well as barriers to trans competent legal representation and recognition of family relationships.Footnote 57

An early Québec case rendered in 1988, Droit de la famille – 480,Footnote 58 demonstrates the creative use of family law by a single trans parent to obtain legal recognition of his relationship to his biological child. The trans parent was originally designated as his child’s mother on the birth certificate. After transitioning from female to male, the trans parent sought to be reclassified as his child’s father.

Unable to correct his child’s birth certificate through the civil law remedy of rectification, the trans parent instead applied to adopt his own child. He provided his consent to the adoption as his child’s mother and adopted his child as the child’s father. The youth, fifteen-years-old at the time of the judgment, supported his parent’s application. The youth emphasized his desire to carry a birth certificate that matched his (only) parent’s name and gender identity and described the potential embarrassment and intrusion caused by carrying a birth certificate bearing a non-congruent parental name and designation.Footnote 59 The application was also supported by the youth’s social worker.

After reviewing the legal framework for changing sex and for adoption, the Court concluded that the legislature had left a legal void for trans parents and their children, apparently having failed to consider the impact of the change of name and sex of a trans parent on their child’s birth certificate.Footnote 60 The Court determined that there was no legal barrier to a parent adopting their own biological child. Invoking the best interests of the child and its parens patriae power, the Court granted the adoption. The trans parent’s name was struck as mother, and he became the child’s legal father.

Droit de la famille – 480 provides an example of a creative and unexpected use of family law to achieve legal recognition for a trans person of their familial relationship. The remedy in this case had limited reach as a legal solution. René Joyal notes that it would only be available to a single parent.Footnote 61 Despite its narrow application, the case reminds trans advocates to be agile in pursuing remedies for trans legal marginalization.

Sixteen years later, another trans parent was unable to obtain a similar result. In J.M. c Québec (Directeur de l’état civil), the trans parent sought to rectify their children’s birth certificates.Footnote 62 The Québec Court refused to allow the parent to change their parental designation from “mother” to “father” on their children’s birth certificates, even after being presented with psychological evidence that it would be in the best interests of the children.Footnote 63 The Court declared that despite any harassment or possible inconveniences the children’s birth certificates may cause, a mother or father at the time of birth always remain a mother and father from a legal perspective, regardless of any subsequent medical transition.Footnote 64

Human rights law may ultimately remedy the legal incongruence of parental designations for some trans parents in Québec. The Civil Code of Québec provisionsFootnote 65 that require a parent to be listed as a “mother” or “father” and the interpretation that parents must remain legally frozen in those designations are currently the subject of a human right challenge.Footnote 66 Some administrative concessions have been granted, including the ability to be listed as a “filiation” rather than a “mother” or “father.”Footnote 67 Family law reform in Québec may eventually allow for more than two parents on Québec birth certificates, following in the footsteps of British Columbia and Ontario.Footnote 68

We know, however, that human rights challenges and law reform take time, and they will likely still leave some people behind. Even progressive law reform attempts leave out those that legislators did not see or were not ready to recognize. In 2016, Ontario’s All Families Are Equal Act changed references from “mother” and “father” to “parent,” including replacing its reference to “birth mother” with “birth parent.” In British Columbia, however, although the 2011 Family Law Act allows a child more than two legal parents and the birth certificate issued lists only the designations of “parents,” a birth parent is still considered to be the “birth mother” under that legislation.Footnote 69 This gendering of the birth parent remains despite the fact that other British Columbia laws were amended with the passing of the BC Family Law Act to change references from “mother” and “father” to simply “parent.”Footnote 70

Trans-sensitive readings of doctrines like the “best interests of the child” will also be determinative in family law jurisprudence going forward. Johanne Clouet analyzes two Québec cases involving a trans parent (issued in 2013 and 2015, respectively) and questions whether stigma may have influenced the decision-maker in one of the cases.Footnote 71 She argues that the malleability of the concept of the “best interests of the child” allows judges to import their own biases. In the 2013 case, Droit de la famille – 133870, the judge went against one expert’s recommendations for joint custody and awarded sole custody to the cisgender parent. Clouet questions whether the judge’s decision not to award joint custody was influenced by prejudice, noting that the judge relied on an expert’s opinion that the cisgender parent’s more traditional family environment would put less pressure on the child.Footnote 72

The effect of a parent’s trans identity on custody and access recently returned as a central concern after a trial judge in the United Kingdom reluctantly concluded that an ultra-orthodox Jewish community’s rejection of trans identity justified denying a trans parent physical access and visitation rights to their children.Footnote 73 The cisgender mother argued that the trans parent should not have contact because of the ultra-orthodox community’s strong anti-transgender values, as access rights would lead to the children’s social exclusion in the community. The Court ordered that the trans parent’s contact with the children be limited to indirect contact four times per year.Footnote 74 J v B was overturned on appeal on the basis that the trial court failed to appropriately consider the children’s welfare and the need to promote parental contact with children.Footnote 75

Although J v B occurred outside of Canadian jurisdiction, the case is the subject of debate between Canadian legal commentators as to how a similar fact set would be decided in Canada.Footnote 76 Claire Houston notes that Canadian courts are bound to uphold the Charter and Charter values, but the Charter cannot be applied to counter a child’s best interests. She argues that it would be in the best interests of the children, in this case, to deny access to the trans parent, even if it may go against trans equality more generally. Joanna Radbord disagrees with Houston’s assessment, finding that the court’s duty to promote maximum contact with parents, regardless of the discriminatory views of another parent or community, would lead a Canadian court to find in favour of access for the trans parent. The case demonstrates how a lawyer’s presentation of evidence regarding the best interests of a child and their arguments about family law doctrines may be determinative in a similar case involving a trans parent in Canada.

Family law cases are decided on a case-by-case basis, with discretionary consideration of each family’s circumstances. Advocates should be prepared to marshal family law tools and evidence that may carry the day. This marshalling includes citing prior jurisprudence establishing that trans identity should not be a factor in and of itself in determining custody and access and the use of expert evidence to support that an access and custody application is in the best interests of a child.

V. Trans Youth in Family and Youth Protection Law

Family law and youth protection cases involving trans youth also illustrate how non-human rights tools are central to trans legal advocacy. Recent family law and youth protection cases involving trans youth have focused on access to trans healthcare or to identity papers when a trans youth’s parents were not supportive or were in conflict.

1. Trans Youth and Access to Identity Papers

In K.A.B. v Ontario (Registrar General),Footnote 77 a seventeen-year-old trans youth sought to change her name but lacked the necessary parental consent. K.A.B.’s mother was not supportive of her child’s transition, and her family was described in a counsellor’s letter to the Court as “quite transphobic.”Footnote 78 K.A.B. was living away from her mother’s home, attending school, and accessing healthcare herself.

Under Ontario’s Change of Name Act,Footnote 79 a person under eighteen years of age requires written parental consent from “every person who has lawful custody of the child.” An applicant for a change of name may apply to the court to waive the need for parental consent.Footnote 80 In evaluating such an application, the court will consider the best interests of the child.

K.A.B.’s initial application for a change of name was denied due to the lack of parental consent, and she applied to the Court for an order to dispense with the parental consent requirement. In assessing her application, the Court considered the meaning of “lawful custody.” It concluded that her mother did not have lawful custody, as K.A.B. made her own healthcare, schooling, and housing decisions and the mother had no physical or other control over K.A.B. The court granted K.A.B.’s request for a change of name.

Numerous studies have highlighted the challenges that trans youth face in Canadian society, with exclusion by family members a significant risk factor for mental health distress and homelessness.Footnote 81 Trans people in Ontario experience major barriers to employment, in part due to a lack of identity papers that match their gender identity.Footnote 82 The legal tools enabling trans youth to emancipate themselves from unsupportive parents will be a key site of trans rights advocacy going forward.

2. Trans Youth and Access to Trans Healthcare

Another case involving the relationship between a trans youth and their parents who were initially not supportive shows how youth protection law was used to facilitate a trans youth’s access to trans healthcare and to improve their home life. In Protection de la jeunesse – 101683, youth protection became involved when a trans youth was lacking family support.Footnote 83 The youth was struggling with their gender identity and experiencing suicidal thoughts and anxiety. They were also facing bullying in school.Footnote 84

The Court of Québec ordered interim measures including providing the youth with access to trans healthcare professionals, and ultimately, the mother became supportive. The Court’s final decision provided that the youth should be in the care of their mother but continue to access trans healthcare as long as they wished to.Footnote 85 The decision also went further: the Court instructed the youth’s parents to ensure that family members were told to refrain from making derogatory comments about the youth in the youth’s presence.

In a British Columbia case, A.B. v C.D. and E.F. (AB v CD), a fourteen-year-old trans youth used family law and health law to gain protection from an unsupportive parent and facilitate access to trans healthcare.Footnote 86 The youth, A.B., sought a protection order to stop his father from speaking publicly about his personal and medical information. The father opposed A.B.’s wishes to begin gender-affirming hormone therapy. He spoke to the media about his objections and provided interviews outing A.B. featured on websites critical of gender transitions by children and youth.

The trial court found that A.B. had the exclusive capacity to consent to trans-related healthcare.Footnote 87 The British Columbia Supreme Court further declared that the behaviour of the father when he misgendered A.B. or tried to talk A.B. out of gender-affirming healthcare constituted “family violence.” Footnote 88 It found A.B. to be an “at-risk family member” under section 182 of the Family Law Act and issued an order to protect A.B. against family violence by his father. The father appealed.

The British Columbia Court of Appeal agreed that A.B. had the capacity to consent to hormone therapy but narrowed the scope of the youth’s capacity to consent to the hormone therapy treatment that was before the Court.Footnote 89 Future trans healthcare treatments would require “fresh consent.”Footnote 90 The Court of Appeal also substituted the protection order addressing “family violence” with a conduct order preventing the father from publishing information on A.B.’s gender identity and related issues, whether directly or through a third party.Footnote 91 The protection order was found by the Court to be inappropriate as intention to commit family violence was not found in the evidentiary record.Footnote 92 Following the decision, West Coast LEAF, an intervenor at the appellate level, expressed concern that the Court required a finding of intent to harm for conduct to constitute family violence.Footnote 93

A.B. v C.D. has much to teach legal advocates. A trans youth under significant distress and seeking medical care received access to that care through the tools of family law and health law. The initial orders by the trial court were deemed too broad at the Court of Appeal. Advocates must be prepared for the potentially recurring work of legal challenges to a trans youth’s capacity to consent for each respective treatment. The Court of Appeal’s replacement of the protection order with a conduct order is also instructive. Advocates should be mindful of courts’ potential desire to be less intrusive in family affairs. Where broader remedies are not successful, more restrained legal tools may obtain similar, albeit more limited, results.

3. Supporting Trans Youth

In these trans youth cases, we see again how family law and youth protection law can be instrumentalized in advocating for trans rights. Adler urges legal advocates to consider law reforms that improve marginalized LGBTQ youth’s material realities by addressing laws that prevent minors from changing their identity papers, accessing healthcare, signing leases, and obtaining employment.Footnote 94 Such reforms include addressing legal barriers to youth signing leases on apartments and obtaining access to credit.Footnote 95 In Canada, some of this legal work will be grounded in pleadings about the just interpretations of “best interest of the child,” “lawful custody,” “family violence,” and the ability of youth to consent to healthcare. Other work may require legislative or policy changes, such as advocacy efforts to extend youth’s access to financial support after they age out of the child welfare system.

Improving the material lives of trans youth calls for pragmatic advocacy using legal and non-legal tools. It will require working with children and youth lawyers, the judiciary, the government, and support services to build understandings of trans realities while also being prepared to make meaningful legal interventions to directly support trans youth.Footnote 96 The need for agile advocacy in this area will remain vitally important, as trans youth continue to have less access to resources and to trans competent legal representation.

VI. Disclosures of Legal Name and Gender in the Justice System

One of the ways that trans people are marginalized by the legal system relates to how the police and court systems name and gender trans people. Consider that Brandon Teena, whose murder in 1993 was widely reported and later fictionalized in the movie Boys Don’t Cry, was killed after being outed by the criminal justice system when he was charged for forging a cheque, through the publication of his arrest record bearing his legal name in a weekly paper.Footnote 97 Trans people, particularly criminalized trans women, may experience this potential outing when their arrests are publicly reported listing their legal names, making them more susceptible to violence and discrimination.

Turning to trans jurisprudence then, how are courts and tribunals naming and gendering trans people? Open court principles expose people to the public airing of their interactions with the legal system. Trans people face a potential double punishment: a public airing of their legal issues, and their outing, resulting in a risk to their social, financial, and personal security. A significant body of case law has developed allowing trans parties anonymity (through the use of initials) in order to bring their human rights claims forward,Footnote 98 without which many trans claimants may not have been willing to seek remedies for discriminatory treatment against them.

Courts and tribunals also have a significant role to play in how trans people experience the justice system, including by referring to a trans party by their chosen name and gender, even if these have not been legally changed. There is no apparent legal barrier to courts and tribunals respecting a trans person’s chosen name and pronouns during hearings. Similarly, no such barriers exist to respecting a trans person’s name and gender in written decisions, as long as there is some link to the party’s legal name to the extent necessary for official record-keeping. Nonetheless, Canadian courts and tribunals have been inconsistent when asked by a trans party to use a pronoun different than their legal gender.

In Montreuil v National Bank of Canada,Footnote 99 the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal described this inconsistent treatment by the courts and tribunals when considering the trans complainant’s request to be referred to by female pronouns:

[4] The Complainant has acted as a party to proceedings before several courts, including the Federal Court, the Superior Court of Québec, and the Court of Appeal of Québec, on matters relating to the name by which she may be permitted to identify herself. In the judgments rendered in these cases, the Complainant has been referred to either by the female or the male gender, depending on the decision-maker. For instance, in the case of Montreuil v. Directeur de l’état civil, Madam Justice Rousseau-Houle applied the female gender, whereas Mr. Justice Morin, noting that the Complainant is still physically a man, used the male gender in his dissenting reasons.

The Tribunal went on to determine that it saw no reason to deny the Complainant’s request to use female pronouns.Footnote 100 Despite the Tribunal’s decision to respect the complainant’s chosen gender, in another case decided five years later by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal in 2009, the Tribunal used masculine pronouns to refer to the Complainant.Footnote 101

In a 2009 youth protection case involving a trans youth who identified as male, the Court of Québec emphasized that it was sympathetic to the youth, but was unable to refer to him by male pronouns because the youth was legally female, and it did not want to add further confusion to the youth’s situation.Footnote 102 In Montoya Martinez v Canada (Minister of Citizenship & Immigration), one of the factors raised in support of an application for judicial review of a decision rejecting a couple’s claim for refugee status was the decision-maker’s repeated misgendering of one of the claimants. Footnote 103 The decision-maker referred to the transgender man in the couple as a transsexual woman and called him by female pronouns.Footnote 104 The Federal Court described the misgendering as a terminological slip that was unfortunate but found that it did not constitute a misapprehension of the facts and the dangers faced by the claimant.Footnote 105

There is a growing body of case law in which courts do refer to trans parties by their chosen pronouns. In 2013, in K.A.B. v Ontario (Registrar General), the Ontario Court of Justice stated simply that the applicant preferred female pronouns and would be referred to as such in the decision.Footnote 106 In 2017, in a case involving a trans minor, the Ontario Court of Justice noted that the youth is gender-fluid and used gender-neutral pronouns in its written decision.Footnote 107 In Beaumann v Canada (Minister of Justice), the Court of Appeal for British Columbia noted that a trans appellant preferred to use female pronouns, and went on to use those pronouns throughout the judgment.Footnote 108

To be referred to by a name or gender that is not one’s own will evidently impact one’s ability to participate fully in proceedings and to be heard and understood. It may also have significant safety consequences. In determining how to refer to trans people, judges, tribunal members, and other decision-makers have considerable influence on how trans people will experience the justice system, and how their lives will be impacted by those interactions. At the same time, Aizura argues that some trans people, such as trans immigrants, may not want to disclose their trans status to the state.Footnote 109 Pragmatic and flexible trans legal advocacy requires lawyers to resist default assumptions and create space for trans people to choose how to reduce the harm they experience as they navigate intersecting systems of exclusion.

VII. Access to Social Benefits

Explicit trans human rights protections have increased public education about and awareness of trans rights. Some employers and service providers may take action to change discriminatory environments and policies, and the number of trans people who seek out remedies for discrimination may increase. Societal change is slow, however, and socio-economic data shows that trans people continue to face significant unemployment and underemployment due to social stigma and prejudice.Footnote 110 Trans people in Ontario report a median income of $15,000. Given ongoing societal discrimination and systemic violence against trans people, particularly Black trans women, trans women of colour, and Indigenous trans and two-spirit people,Footnote 111 unemployment and underemployment are a central part of trans marginalization.Footnote 112

With those structural barriers in mind, trans jurisprudence locates access to social benefits as an important site of trans legal advocacy. The case law indicates that some trans people need access to disability benefits due to the mental health effects of daily discrimination and a lack of access to health and social services. The TRANSforming Justice trans legal needs assessment highlighted access to disability benefits as a key legal issue, with trans people in Ontario reporting their legal needs relating to disability benefits at 15% compared with 1.6% for the general Canadian population.Footnote 113

In 2014, in 1306-06132 (Re),Footnote 114 a trans person unsuccessfully appealed their denial of disability benefits. The central question for determining a person’s eligibility for benefits is whether the person has a disability whose impairments meet the threshold of substantial. The Appellant described a number of conditions including major mood disorder, gender identity disorder, depression, reduced energy, low concentration and motivation, and insomnia.Footnote 115 The Tribunal emphasized that discrimination against trans people, or fear of discrimination, does not in and of itself qualify as substantial impairments.

Although gender identity may well give rise to discrimination, the issue before this Tribunal is whether the Appellant was disabled at the relevant time within the meaning of this legislation. In this sense, gender identity is not in and of itself a disability related impairment – although, as discussed above – it may well be directly related and causally linked to disabling mental health conditions. Footnote 116 [emphasis added]

The appeal was dismissed, with the Tribunal determining that there was insufficient evidence of substantial impairment.

In another case in 2014, 1401-00532 (Re), the Appellant was successful in their appeal.Footnote 117 The Tribunal determined that the Appellant did qualify for disability benefits based on the mental health effect of the prejudice and barriers faced due to living as a trans person in Ontario society.Footnote 118 In that judgment, the Tribunal also noted the long waiting lists for hormone therapy, accounting for the impact of limited access to trans healthcare on trans people’s health.Footnote 119

In 2017, there were eight reported cases of trans people appealing a negative decision to the Ontario Social Benefits Tribunal. Three of those appeals were dismissed,Footnote 120 and five were successful.Footnote 121 In one of the successful cases, the Tribunal explicitly noted that gender-affirming healthcare may subsequently improve the claimant’s health and ability to socialize and work.Footnote 122

Social benefits cases appear to turn on the level of medical evidence provided by the claimant and the extent to which that evidence directly addresses the claimant’s substantial impairments. The evidence must demonstrate a substantial impairment that limited the claimant’s “ability to attend to his or her personal care, function in the community and function in a workplace.”Footnote 123 If trans rights account for the effect of structural barriers and societal prejudices on trans people’s health and ability to obtain and maintain employment, then trans legal strategies must include support for access to income support and disability benefits. Given that trans people have limited access to trans competent healthcare, such advocacy work should include building networks of trans competent healthcare professionals. Advocates must also be particularly vigilant in the political realm, as governments cycle through austerity measures that cut or limit benefits to people living in poverty.

VIII. From Trans Rights to Trans Justice

As trans law reforms continue to sweep across Canada, advocates invested in trans legal changes that improve the lives of trans people on the margins must be prepared to look both inside and outside human rights law. We know the limits of formal equality—that it must be distinguished from substantive equality, that it may have unintended impacts, that its compromises often leave the most marginalized behind.Footnote 124 Law reforms are rarely as effective as we hope them to be. They do not necessarily ease the impact of daily discrimination, including social stigma, barriers to employment, and limited access to healthcare. In After Legal Equality: Family, Sex, Kinship, Robert Leckey notes that some marginalized groups may consider successful law reform the victorious end of their mandate, when there is in fact much work left to do.Footnote 125 Trans legal advocates should similarly be wary of overinvesting in trans human rights as the means for materially improving trans lives.

Trans jurisprudence helps reveal sites for trans legal strategies that are left out of equality rights discourse. As Libby Adler argues, a focus on distributive justice shifts our “gaze away from grand aspiration and principled vindication and redirect[s] it downward, toward the gritty, low-profile rules, doctrines, and practices that condition daily life on the margins.”Footnote 126 A pragmatic, intersectional, and flexible approach to trans justice is grounded in the daily realities of trans lives. It moves away from the promises of equality rights to the grinding work of creative legal advocacy, navigating the doctrines of family law and consent to healthcare by youth, challenging the misgendering of trans people by the justice system, and marshalling evidence to support access to social benefits.

This article has provided just a few examples of trans legal work outside of human rights law. There is much more work to do. Dean Spade calls on trans advocates to centre survival and distribution, and the needs of those most at the margins.Footnote 127 Libby Adler notes the absence of LGBT advocacy groups in fights against bylaws preventing people from sitting or lying down in public places.Footnote 128 Such laws directly target homeless people, with trans youth disproportionately represented in homeless populations. To support trans migrants facing racism and transphobia, legal advocates often must navigate the rules of the immigration system. Trans migrants who do not disclose changes to their legal identity before entering Canada may face allegations of misrepresentation which threaten their status in Canada. A trans woman who did not declare her former legal identity upon entering and ultimately immigrating to Canada faced a removal order from Canada for misrepresentation.Footnote 129 To overcome the removal order, she needed to demonstrate that, based on a number of factors, including her ties to Canada and the seriousness of her misrepresentation, she should not be removed from Canada. While trans human rights developments may have influenced the decision-maker, the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada’s decision focused on the established factors when considering removal for misrepresentation and found that the appellant demonstrated sufficient humanitarian and compassionate grounds to prevent deportation.

For trans people struggling with legal issues relating to access to housing, as reported in large numbers in the TRANSForming Justice report, legal strategies should include fighting for rent stability and against the criminalization of homelessness.Footnote 130 For trans people facing incarceration, courts should be asked to consider the difficulties that trans people face in custody when a sentence is determined. For trans youth seeking access to identity papers or trans healthcare, legal strategies require able representation by legal counsel to fight for trans youth’s increased agency. Nora Butler Burke describes the double punishment faced by migrant trans women who sell sex in Canada from both the criminal justice system and the immigration system.Footnote 131 For trans migrants with criminal convictions, intersectional trans legal advocacy may include support navigating the Canadian immigration system to help secure Canadian citizenship.

Beyond the legal strategies canvassed in this article, there is much more work to do to identify legal priorities that centre distributive justice and trans survival. Trans jurisprudence and trans legal needs assessments provide us with starting points. Trans justice is guided by the pressing needs of marginalized trans people. It goes beyond legal recognition through explicit human rights grounds and turns to the substantive work of helping marginalized trans people survive—by increasing access to low-cost housing and social benefits, decriminalizing sex work and drug use, fighting against racial profiling, supporting trans parents and trans youth, and through other projects that increase trans people’s life chances.Footnote 132

Pragmatic, trans-led legal advocacy must be creative and fierce. It centres the needs of trans people on the margins who identify the legal work needed to materially improve their daily realities. Trans rights are then advocated for by using whatever legal tools are required, both within and outside human rights.