No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 July 2014

1. The Constitution protects property rights in other ways nonetheless: by prohibiting the impairment of obligations, the contract clause protects a party's proprietary interest in the performance of bilateral promises; the commerce clause has been interpreted in the past to protect laissez-faire interests; moreover, the fourteenth amendment's due process and equality clauses, together with first amendment guarantees, have also generated doctrines protective of proprietary rights.

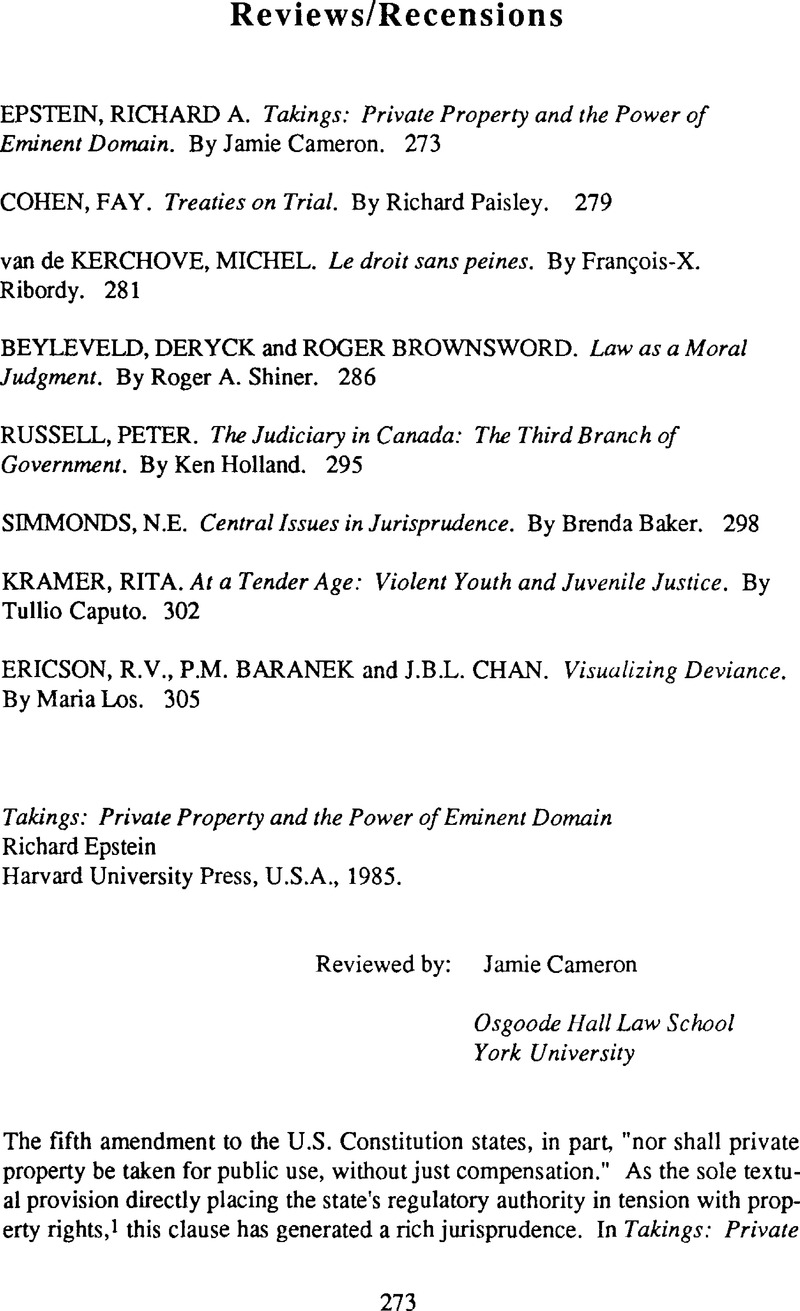

2. Epstein, Richard, Takings: Private Property and the Power of Eminent Domain (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1985)Google Scholar, Preface at viii. At ix, he adds that “[t]he rules of public law make sense only if they can be “reduced” to propositions that are understandable in private-law terms.”

3. Ibid., 36.

4. Chapters 4 to 8.

5. Chapter 5, Partial Takings: The Unity of Ownership.

6. Chapter 8, Taking From Many: Liability Rules, Regulations, and Taxes.

7. Even here, Epstein finds a private law analogue in the justificatory defences of self-defence and necessity. Ibid., 111. In this context, as in other parts of the analysis, it is problematic to graft private law conceptions onto public law analysis. I discuss this point in further detail, elsewhere.

8. The police power operates as a limitation on all Bill of Rights guarantees. Just as the first amendment cannot be invoked to challenge a conviction for perjury, the takings clause does not preclude the state from regulating harmful activities occurring on private property. In such cases, the state typically does not take through expropriation; it takes by regulating uses that constitute nuisances by virtue of the harms they cause. Chapter 9, The Police Power: Ends.

9. Chapter 12, Public Use.

10. Chapters 13 through 19 deal with the “just compensation” requirement.

11. Ibid., 25.

12. Ibid., 85.

13. Ibid.

14. Chapter 2, Hobbesian Man, Lockean World.

15. Though there is a rich literature discussing the republican conception of the Constitution, Epstein neither refers to it nor supports his own assertion about the prevalence of Lockean philosophy.

16. Ibid., 134-145.

17. It remains unexplained because any argument that economic liberty has been less important in American constitutional culture would not be persuasive. Moreover, because the Constitution is given to opportunistic interpretation, it is also difficult to maintain that the text favours non-economic liberty to the exclusion of economic liberty.

18. Thus he does not suggest putting economic and non-economic liberties on a par by giving speech, liberty or equality values less protection. Similarly, he does not suggest that the roles be reversed, as they were in the early twentieth century, so that economic liberty would be preferred to non-economic liberty. Nor in defending the Lockean conception does he rely on “original intent” as his jurisprudential source of authority.

19. Chapter 3, The Integrity of Constitutional Text.

20. Ibid., 20.

21. See Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803).

22. Chapter 9, The Police Power Ends.