Introduction

For over half a century, it has been axiomatic that environmental claims are particularly well-suited to class actions (Cappelletti and Garth Reference Cappelletti and Garth1978; Hensler Reference Hensler2009). In every country where class actions have been introduced as legal transplants since their introduction in the United States in 1966, environmental claims have been spotlighted for relatively straightforward reasons. These include the collective nature of environmental harms and the negligible public enforcement of environmental rules and regulations, which precipitates demand for private enforcement. Strong formal economic reasoning informs this view: class actions involve negative value claims that would not otherwise be individually brought by economically rational actors—the economic cost of individually pursuing such claims outweighs the benefits. The risk of adverse costs also features in such economic calculations in jurisdictions that uphold the “loser pays” principle (like Ontario). Formally, then, a legal vehicle that aggregates negative value claims to the point where the totality becomes positive value—and therefore economically rational to pursue—can be said to advance access to justice by making economical claims that would otherwise remain unvindicated. There is additionally a strength-in-numbers logic in class actions that can be viewed as promoting accessibility to the extent that many such claims involve acute power imbalances between victims and wrongdoers (e.g. residents of a polluted community against a transnational corporation). The collective power of class actions can thus strengthen otherwise isolated and weak individuals against powerful adversaries. These dynamics are particularly evident in environmental claims, which also typically involve diffuse harms across vast spatial and temporal contexts. The idea that environmental claims are well-suited for class actions thus appears to be on solid theoretical and economic footing.

In Canada, sociolegal scholars have tended to approach collective environmental claims from the standpoint of the legal mobilization and social movement literature (Agyeman et al. Reference Agyeman, Cole, Haluza-DeLay and O’Riley2009; Wiebe Reference Wiebe2016; McLeod-Kilmurray Reference McLeod-Kilmurray2007). The treatment of class actions in this scholarship has either been entirely absent or limited to brief references without fully exploring their functioning and limitations—a research field that has almost exclusively remained in the domain of civil proceduralists. This is regrettable given the political, economic, and social dynamics of class actions. Indeed, Michael McCann (Reference McCann, Caldeira, Kelemen and Whitington2009) and Deborah Hensler (Hensler, Hodges, and Tzankova Reference Hensler, Hodges and Tzankova2016) have both identified this knowledge gap and called for greater focus by social scientists on class actions in their broader context. With collective environmental problems on the rise, a deeper appreciation of the merits and limits of the civil procedure will certainly contribute to scholarship in this field. As a matter of interdisciplinary orientation, then, this article thus takes the view that social science research, especially political science and sociolegal studies, stands to benefit from greater engagement with class actions.

This article aims to contribute to this underexplored field by examining the development of environmental class actions in Ontario. The central contention is that the actual functioning of environmental class actions has been marked by severe restrictions and an inhospitable legal climate that has limited their access-to-justice capacities. By developing this counter-narrative, the article hopes to offer greater clarity about the uses and limits of class actions in environmental claims moving forward. Starting with a brief overview of class action history in Canada and the economics of mass litigation at a general level, the article then explores issues specifically facing environmental claims, with a focus on the interconnected problems of establishing toxic causation and the paradigm of scientific uncertainty. A series of representative case studies is then presented to substantiate the central contention. To this end, the article takes an integrated approach that examines the relevant empirical, economic, procedural, and political factors and dynamics, which, together, can offer a composite picture of the type of access to justice that is presently achieved and achievable for environmental claims.

A few introductory notes before beginning: First, this article uses the term “multilayer access to justice” to refer to access to justice in the context of class actions. Multilayer refers to the multiple layers of interests at stake in class actions—individual, collective, and public—and was originally introduced by Stefan Wrbka, Steven Van Uytsel, and Mathias Siems (Reference Wrbka, Uytsel and Siems2012). Second, the legal actors that this article addresses are class action attorneys, given the reversed recruitment paradigm of class actions in Ontario; that is, the prevailing norm in class actions is a paradigm whereby attorneys recruit their clients rather than clients recruiting their attorneys. In Canada, these actors are predominantly “commercial attorneys” rather than “public interest attorneys.” Although class actions invariably engage with public interests (hence the term multilayer) and such commercial lawyers can be viewed as “private attorneys general,” the small world of class actions in Canada is dominated by a select few commercial firms whose decision-making is largely based on market criteria and principles, as opposed to the heterogeneity in legal actors that one finds in other areas of the law. Third, this article focuses on the barriers posed to potential claimants in environmental class actions. These include the gatekeeping role played by class attorneys—a facet of class actions that applies across sectors—as well as barriers specific to environmental claims. The focus is thus largely procedural rather than outcome-oriented. In fact, the notion of barriers is proceduralistic, as it denotes obstacles to having one’s day in court. In this sense, barriers corresponds to the access portion of “access to justice.” Barriers are typically obstacles confronted by potential claimants at the outset of a justiciable problem. Given the short space permitted here, it is largely beyond the scope of this article to address the challenges facing claimants at the close of a justiciable problem—these can be understood as corresponding to the justice portion of “access to justice.”Footnote 1 This article thus has the more modest objective of identifying and exploring the accessibility barriers faced by potential claimants in environmental class actions in Ontario.

Multilayer Access to Justice in Canada

Canada is not an exception to the optimistic belief about environmental class actions. From the outset, in the various legislative debates and commissioned reports that ushered in Canadian class action regimes, including the influential Ontario Law Reform Commission’s Report on Class Actions (1982) that precipitated Ontario’s Class Proceedings Act, 1992, there was a widespread consensus on the suitability of such claims for the exciting new legal procedure. This background has been well examined by legal historian Suzanne Chiodo (Reference Chiodo2018) and warrants a brief glance. Despite Quebec being the first Canadian province to introduce class action legislation in 1978, it was Ontario’s legislation that was the watershed for the rest of the Canadian provinces, which followed suit in the following years: British Columbia in 1995, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador in 2002, Manitoba in 2003, and Alberta in 2004 (class actions were adopted into Canadian common law and extended to all remaining provinces following Western Canadian Shopping Centres v Dutton [2001]). The promise of environmental harms being addressed through the use of class actions was repeatedly highlighted by legal reformers due to the relatively straightforward reasons described at the outset of this article. In the access-to-justice literature, this aligns with the Second Wave recognition (to borrow the “wave” metaphor, which refers to the successive eras of access-to-justice policy reform in the post-war era), as described in Mauro Cappelletti and Bryant Garth’s cornerstone The Florence Access to Justice Project (Reference Cappelletti and Garth1978), that diffuse and collective interests require collective redress mechanisms like class actions to ensure accessible justice.

The early uncertainty about the ways in which class actions would develop among legal actors was relieved with the trilogy of decisions that opened the floodgates: Western Canadian Shopping Centres v Dutton (2001); Hollick v Toronto (City) (2001); and Rumley v British Columbia (2001). In Dutton, the Supreme Court of Canada observed that class actions merited introduction into Canadian common law, given their public importance of advancing access to justice, deterrence, and judicial economy, irrespective of provincial statutory regimes. In Hollick, the Supreme Court developed what is now known as “the Hollick approach,” which is a more generous approach to certification—an impactful development, since the pre-trial certification stage is one of the most important junctures for prospective claims. Hollick was also the first certification application for an environmental class action (and it was ultimately denied). In Rumley, the Supreme Court broadened its understanding of multilayer access to justice beyond economic factors by recognizing social and psychological barriers. Taken collectively, this trilogy of decisions signalled a new era for class action litigation in Canada from an access-to-justice perspective. For those hoping for an increase in multilayer access to justice in environmental matters, however, this optimism was short-lived, at least in common law provinces.

Environmental class actions were among the first to be advanced across Canada, to mixed results. As noted above, the first environmental class action in Ontario, Hollick, was denied certification. In British Columbia, the first environmental class action was also not certified—Sutherland v Canada (Attorney General) [1997]. This was similarly the case in Saskatchewan in Hoffman v Monsanto Canada Inc. [2007], where certification was denied. In the well-known Agent Orange case (discussed below) in Newfoundland and Labrador, Ring v Canada (Attorney General) [2007], certification was initially approved and rejected on appeal. In New Brunswick, another Agent Orange case (also discussed below) was not certified in Bryson v Canada (Attorney General) (2009). In Alberta, two class actions were the first two actions in the province, with one being certified—Windsor v Canadian Pacific Railway (2007)—and the other being denied—Paron v Alberta (Minister of Environmental Protection) [2006]. In Nova Scotia, the so-called Sydney Tar Ponds action was ultimately certified in 2011—MacQueen v Sydney Steel Corp. [2011]. Finally, the first environmental action in Manitoba was certified on appeal in Anderson v Manitoba [2014]. These were the first forays into environmental class actions across Canada, and their mostly negative results have been indicative of the ways in which such actions have developed in common law provinces since then.

Quebec has developed along its own trajectory due to a confluence of economic, doctrinal, and procedural factors making it a more plaintiff-friendly jurisdiction, including a strong and universal public funding program (Fonds d’aide aux recours collectifs), the absence of adverse costs awards, a flexible approach to neighbourhood disturbance doctrine, a liberal interpretation by courts of the identical, similar, or related questions of law or fact requirement in the Code of Civil Procedure, and the absence of a “certification” process in favour of a more plaintiff-friendly “authorization” process that (unlike other provinces) does not include a “preferable procedure” criterion, which is one of the major barriers for prospective claims (Durocher Reference Durocher2018). I expand on the features of Ontario’s certification stage in greater detail below, but for now, the last point bears clarification: at the outset in Quebec during its authorization process, which is the initial stage of the action, there is no need for the court to consider alternative procedures to the class action or the justification for proceeding as a class action, unlike in Ontario—rather, it is only necessary for the plaintiffs to demonstrate the impracticability of joinder and representative proceedings. This is a significant feature that contributes to making Quebec a plaintiff-friendly jurisdiction. By way of contrast, the preferability criterion is one of the most cited reasons for dismissal at certification in Ontario. At a general level, then, authorization in Quebec is decidedly less onerous than certification in common law Canada. The proceeding is filed on behalf of the entire class, rather than advancing as individual actions that must be certified in order to proceed as a class action, the alleged facts of the case are considered to be prima facie true, and the defendant cannot contest the motion in writing, but can only do so verbally. Quebec can thus be viewed as a procedural outlier, which reduces the basis for fruitful comparative analysis with the rest of Canada. Although other provinces have some of the above features in their respective regimes, no other province benefits from all of these cumulated.

The poor development of environmental class actions in common law Canada deserves a deeper look. In New Brunswick, both cases that have been initiated have resulted in losses for the plaintiffs; in Nova Scotia, the only case was lost; both cases in Newfoundland and Labrador were lost by the plaintiffs; all three cases in Saskatchewan were lost (one discontinued by the plaintiff after a loss in an injunction application); in Alberta, two out of three cases resulted in losses, while the third was settled; in British Columbia, the plaintiffs have lost four out of six cases, with one being settled and the other still ongoing; finally, in Ontario, the plaintiffs have lost six out of fifteen cases, with eight being settled and one ongoing (Durocher Reference Durocher2018, 1097–99). Clearly in comparison with the poor state of affairs in the rest of the common law provinces, the situation in Ontario might look better on the surface. An easier and oversimplified argument could rather be that the rest of the common law provinces are lagging behind Ontario. As the major common law regime in Canada by volume, however, Ontario has a significantly lower volume of class actions than expected, particularly as a fraction of the total. By way of comparison, there have been seventy-two environmental class actions filed in Quebec’s regime (ibid). Although Quebec’s regime is more senior (originating in 1978), there were only five actions filed between 1978 and 1990, when Alcan was authorized. Even subtracting those five cases, Quebec has seen more cases than the rest of Canada combined by a significant margin. More importantly, as we will examine further below, the actual functioning and the substance of class actions in Ontario leaves much to be desired from an access-to-justice perspective, not least of which is the ways that the scope of environmental claims have been limited in order to attain certification.

Before delving into the substance of the claims, however, it is useful to first examine the empirical background. Consider, at first instance, the steady rise of overall actions since their introduction in the early 1990s.

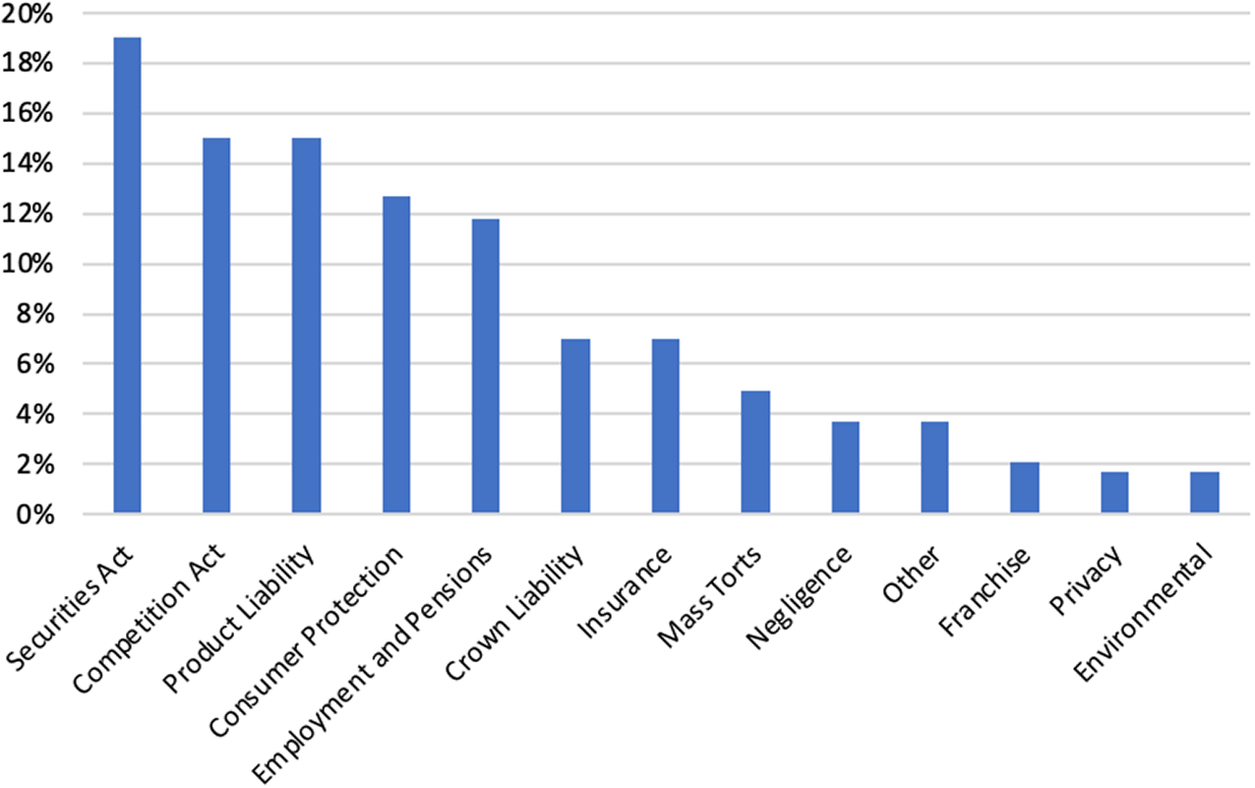

Figure 1 indicates a class action regime that is flourishing. If the preliminary theorisation about the suitability of environmental claims for the procedure were to find empirical substantiation, one would expect that a healthy proportion of this flourishing regime would be taken up by such claims. However, as Figure 2 indicates, the most frequent actions are those that economic analyses of the actual functioning of the regime have indicated: actions involving the Securities Act (16%), Competition Act (15%), and product liability (15%). Environmental claims, once posited as especially well-suited for class actions, have accounted for a mere 1.6% of total actions.

Figure 1 Estimated number of class action matters filed in Ontario annually, 1992–2017.

Source: Law Commission of Ontario, Class Action Final Report (2019).

Figure 2 Estimated types of class actions filed in Ontario, 1993–2018.

Source: Law Commission of Ontario, Class Action Final Report (2019).

This is joint-fewest along with privacy actions. Far from being especially well-suited for class actions, then, the data appears to draw the opposite conclusion. The data gaps in class actions (that Kalajdzic and Piché sought to fill in the Law Commission of Ontario (LCO) Final Report, as the LCO Final Report) similarly extend to certification, although the LCO Final Report does offer a general overview. A recent independent study in Ontario, however, found that between 2010 and 2015, there were 143 decisions rendered, with 112 proceedings certified at first instance across the categories of class actions (Bach and Podolny Reference Bach and Podolny2016). Environmental claims ranked last across this range, which included securities, consumer protection, employment, competition, Crown liability, franchise, investment fraud, pension, intellectual property, and privacy claims. Only a single environmental claim was advanced among the 143 applications for certification (ibid). These findings provide some statistical support for the standpoint that Ontario’s class action regime has shifted at the level of the decision-making of class action attorneys against environmental claims. It is not only that environmental claims are advanced and denied certification, but rather that they have largely ceased to be advanced altogether. It is thus important to examine the economic and legal dynamics that have facilitated this situation.

In so doing, it is pivotal to note that a key facet for understanding how class action regimes function in practice is that there is a reversal of the traditional recruitment process as found in most other areas of the law: in class actions, attorneys recruit their clients as opposed to clients recruiting their attorneys. A recent survey corroborates that such recruitment is the norm in class actions (Kalajdzic Reference Kalajdzic2018). This dynamic attests to the “entrepreneurialism” in which such attorneys engage—motivated by the attractive rewards of collective redress, class attorneys proactively pursue cases that meet their selection criteria, and in so doing, promote access to justice for harmed groups of similarly situated individuals for whom litigation would otherwise be economically irrational. Where there are market incentives for the pursuit of collective action, attorneys as actors in the legal marketplace act accordingly. By extension, of course, this is also true where these incentives are absent; which is to say, without such incentives, class attorneys do not pursue otherwise meritorious claims. The reversed recruitment paradigm is also pivotal for understanding the role played by attorneys as gatekeepers. In a paradigm where attorneys recruit their clients rather than clients recruiting their attorneys, the criteria of recruitment take on the characteristics of barriers. For any accessibility analysis, therefore, case selection is a decisive stage. In Ontario, the criteria used by attorneys are primarily based on imperatives of profitability, predictability, and risk-exposure (Kalajdzic Reference Kalajdzic2018). These criteria are likely different for public interest lawyers and related organizations for whom public importance features more prominently at the case selection stage.

Scientific Uncertainty and Toxic Causation

The prevalence of scientific uncertainty stands among the greatest barriers to environmental litigation, at a general level and at the level of class actions more specifically. This has both a substantive and economic component: it is a significant problem in claims involving human health–impairment, and it also contributes to disincentivizing entrepreneurial attorneys from pursuing otherwise meritorious claims given the diminished prospects of success at trial or, more commonly, the pre-trial certification stage.

The myriad fields of scientific inquiry that are implicated in evidence production are by now rather familiar to environmental scholars. From an economic perspective, procuring expert testimony and research is a capital-intensive process that disincentivizes risk-averse and budget-constrained attorneys. This is particularly true when public research is inexistent or negligible. Without public research, the prospects of mounting an environmental class action are exceedingly remote. The most common domains of knowledge production in environmental class actions are pharmacology, toxicology, and epidemiology. In cases involving public health, the primary field of inquiry is epidemiology, which establishes linkages between a target human population and the distribution of health-impairing events as distinguished by exposures to specific variables. Unfortunately, there is a decided lack of such studies in Canada. This is similarly true for toxicological studies, which focus on the adverse health effects of potential toxicants. The extensive resources necessary for such studies have historically led to situations where toxicants that are generally recognized as poisonous, such as asbestos, benzene, and arsenic, remain open to questionable counter-claims for extended periods of time (Collins and McLeod-Kilmurray Reference Collins and McLeod-Kilmurray2014). In contrast, pharmacological studies are prevalent given the regulatory mandated clinical trials for the introduction of new substances in Canada.

Questions of scientific uncertainty gain prominence at the causation stage in environmental class actions. Without proof of causation in toxic actions, there can be no compensatory damages in the Canadian civil justice system. A substantial body of scholarship has developed over the years to address the problem of causal indeterminacy, and a general consensus has emerged that establishing causation is the greatest doctrinal barrier to multilayer access to justice for environmental claims (Gold Reference Gold1986; Simon Reference Simon1992; Berge Reference Berge1997; Parascandola Reference Parascandola1998; Sanders and Machal-Fulks Reference Sanders and Machal-Fulks2001; Loewen Reference Loewen2003; Klein Reference Klein2008; Hayes Reference Hayes2009; Collins and McLeod-Kilmurray Reference Collins and McLeod-Kilmurray2010).

The scientific uncertainties that inform toxic causation relate to the capacity of a toxic substance to produce an alleged harm, as well as the empirical claim that a particular substance caused a specific harm to the claimants. That is, causation entails a subdivision between (1) generic causation and (2) specific causation—a successful action must typically provide strong evidence relating to both forms. Class attorneys must demonstrate that a particular substance is (1) capable of producing the alleged harm, before demonstrating that (2) the represented class has been harmed by the relevant substance.

At present, there have not been any comprehensive legislative reforms addressing the unequal impacts of traditional causation standards in Canada. The traditional standard for establishing causation is the “but for” test, which examines the proposition that if not for the defendant’s wrongful conduct, the plaintiff would not have sustained the alleged harms; that is, the plaintiff would not have been harmed “but for” the wrongful conduct. This test is administered on a balance of probabilities. Leading Canadian environmental law scholars Lynda Collins and Heather McLeod-Kilmurray have observed, however, that this test “produces manifest injustice” when there is a lack of research data for harmed justice-seekers, particularly when “this uncertainty stems from the defendant’s own failure to investigate its own substance” (Reference Collins and McLeod-Kilmurray2014, 129). It is plain to observe that defendants are incentivized to refrain from such research or suppress damaging findings. It is likewise clear that class attorneys do not have sufficient economic incentives to privately commission robust research. As useful as ad hoc studies by academic researchers may be, it is incumbent on public authorities to fund and undertake such research.

For now, the central question remains: How have these conditions influenced the functioning of Ontario’s class action regime?

Barriers at Certification in Ontario

It is not particularly surprising that procedural barriers play a major role in environmental class actions. After all, the class action is fundamentally a procedural vehicle. Indeed, the barriers that must be overcome at certification are thus trans-substantive: these are applicable across all class actions, not just environmental claims. As with most areas of the law, the vast majority of class actions result in negotiated settlements. In fact, only a single environmental class action has proceeded to trial on its merits. The true battleground for class actions is actually the certification stage—a pre-trial motion of a proceeding seeking certification as a class action. This stage has proven to be so onerous that the Canadian Environmental Law Association even floated the idea, in its public submission to the LCO, to eliminate certification altogether, citing Australia as an example of a jurisdiction without a formal certification stage, although ultimately noting that there is likely not much support, politically or judicially, for such wholesale repeal (CELA 2018, 10).

As per the Class Proceedings Act, certification is not a determination of the merits of the proceeding—it is intended as a strictly procedural stage. Given the pervasive settlement culture in Ontario’s class action regime (like other provinces), the primacy of certification as determinative of the relative success or failure of a class action produces a climate where class actions are not determined on their merits, but rather on these strictly procedural grounds. This state of affairs naturally extends to environmental class actions as well. This is partly why it is important for sociolegal and political scholars to engage more fully with procedural analysis in order to gain a deeper understanding of the limits of this type of private enforcement.

One can scarcely overstate the importance of certification: without being certified, a proceeding cannot move forward as a class action. Although the failure to certify a proceeding does not preclude class members from individually pursuing their claims, the myriad access-to-justice benefits of collective action will be lost unless the proceeding is radically altered to pass certification. Notably, negative value claims would not otherwise be individually brought by economically rational actors. As such, attaining certification is a necessary condition for accessing justice for environmental claims being advanced as class actions.

At certification, a proceeding must meet the following five criteria enumerated in subs 5(1) of the Class Proceedings Act in order to be certified as a class action: (a) a cause of action; (b) identifiable class; (c) common issues; (d) preferable procedure; (e) representative plaintiff. Although certification is generally the procedural battleground upon which class actions are won and lost, this does not apply evenly across the stipulated criteria. The requirements of (b) an identifiable class of people and (e) a representative plaintiff are usually fairly straightforward and easy to satisfy, but the requirements of (a) disclosing a cause of action, (c) commonality of issues, and (d) the preferability of the procedure have consistently proven to be far more difficult. This is borne out by experiential appraisals by both class and defence attorneys, as well as by recent statistical data that substantiates what attorneys have long suspected, as summarized in Figure 3.

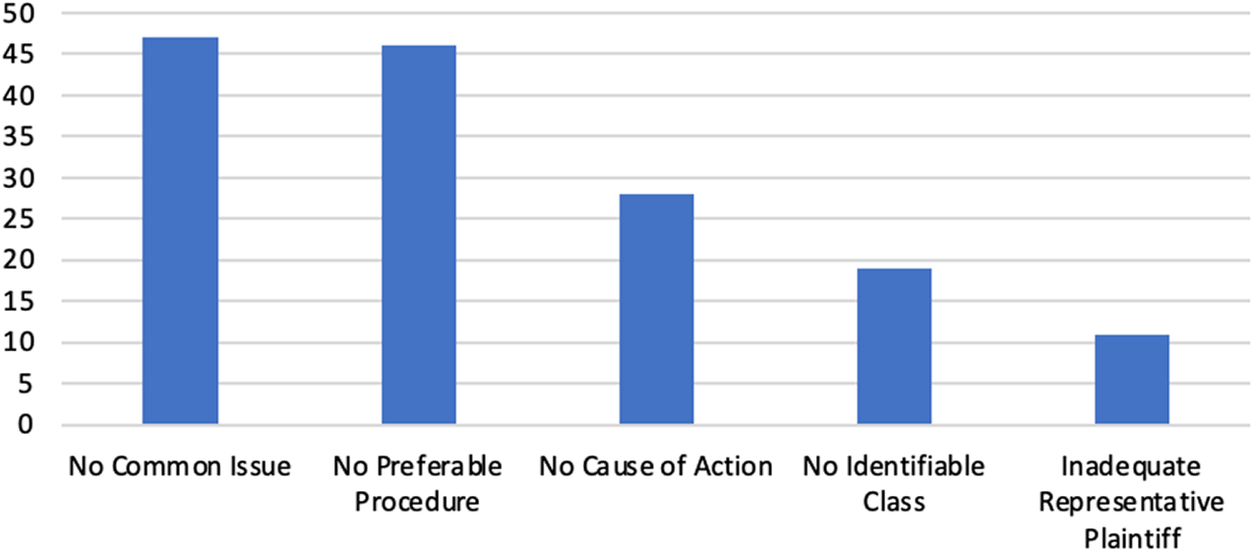

Figure 3 Reasons cited as grounds for dismissal of certification motions, 1993–2018.

Source: Law Commission of Ontario, Class Action Final Report (2019).

According to the LCO Final Report as outlined in Figure 3, the commonality and preferability criteria are the two reasons most frequently cited as grounds for dismissal of certification motions, at roughly 47% and 46%, respectively, with the cause of action criterion cited in 27% cases, the identifiable class criterion cited in 19% and the inadequacy of the representative plaintiff criterion cited in 11% (note: multiple reasons can be cited as grounds for dismissal) (2019, 17). This provides statistical support for what has been recognized in a more qualitative and experiential way for many years among class action practitioners and scholars about the commonality and preferability criteria posing the greatest obstacles to certification.

In December 2019, the Conservative government of Doug Ford introduced a sweeping retrenchment of access to justice in Ontario, including reforms to legal aid provisioning and services. This retrenchment also took aim at class actions, introducing amendments that will likely result in the preferable procedure criterion becoming the most burdensome barrier to overcome for prospective claims. Section 5 now effectively holds that common factual and legal issues need to predominate over those affecting individual class members, which is a test more commonly applied in the United States, where it was introduced as a restrictive barrier, as well as holding that a class action must be the option of the last resort insofar as “it is superior to all reasonably available means of determining the entitlement of the class members to relief or addressing the impugned conduct of the defendant” (LASA 2019, 17).

It is perhaps worthwhile to note at this juncture that the original drafters of the Class Proceedings Act intentionally did not include a predominance requirement in the legislation. By refusing to include such a requirement in the Class Proceedings Act, the drafters sought to expand the purview of possible class actions, given that predominance requirements result in fewer proceedings being certified. This was a positive feature of Ontario’s class action regime, from an access-to-justice perspective—a sharp contrast with approaches typical of American jurisdictions, as well as provinces such as British Columbia that include some form of predominance requirement in their respective statutory frameworks. Politically, the battle over the inclusion or exclusion of a predominance requirement in class action legislation has settled along the now-familiar lines, with partisan interests seeking to limit or restrict class actions lobbying in favour and those seeking to promote the vehicle lobbying against. Despite the outcry of access-to-justice proponents, and dismissive of the recent LCO Final Report, the new Conservative amendments have included a predominance requirement at certification in addition to making class actions the option of last resort, holding that a proceeding is only the preferable procedure if, at minimum, “the questions of fact or law common to the class members predominate over any question affecting only individual class members” (LASA 2019, 17).

With this framework in place, we can now turn to the following case studies, which demonstrate the ways in which the interplay between these procedural requirements and scientific uncertainty has resulted in restricting the scope of environmental claims. Of particular note is the privileging of private property claims over those involving health-impairment, as well as the privileging of single-event claims over those involving historical contamination.

Limiting the Purview of Environmental Claims

From 1918 to 1984, a nickel processing refinery was owned and operated by the transnational corporation Inco Ltd (now Vale Ltd, the world’s largest producer of nickel) in the small town of Port Colborne, Ontario (Pearson v Inco Ltd [2001]). The refinery emitted tonnes of nickel oxide particles into the surrounding environment during this period by engaging in what the trial judge referred to as “abnormally dangerous activities” (ibid). This contamination disproportionately affected the nearby residential area of Rodney Street, a low-income community. According to a comprehensive research study—Soil Investigation and Human Health Risk Assessment for Rodney Street Community, Port Colborne (2002)—commissioned by the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, an international panel of experts determined that elevated levels of nickel and lead contamination warranted action (the presence of other toxicants was also discovered, including arsenic, antimony, beryllium, cadmium, cobalt, and copper). Pursuant to this incurred harm, the residents of the Rodney Street community bound together for a class action to recover damages for the toxic exposures and risks posed to human health and the natural environment, in addition to the devaluation of private property values in the surrounding area.

The class proceeding was initially denied certification, but this was overturned by the Ontario Court of Appeal. In between these two decisions, the claim underwent significant changes. As the Court of Appeal observed, the original claim “was much broader and included sweeping claims for damages from the alleged adverse health effects from nickel oxide contamination” (Pearson v Inco Ltd [2006], at 3). The modified claim, on the other hand, had been “significantly narrowed […] to damages for the devaluation of real property values arising from soil contamination” (ibid). To be precise, the devaluation of real property values referred not to any decrease in property values per se, but rather to the slowing of property appreciation as a consequence of the stigma from nickel oxide contamination. This narrowing of the scope of the claim was not inconsequential. According to the Court of Appeal, the appeal called upon the court to “consider whether a class proceeding is a suitable vehicle in an environmental case” (ibid at 1), quoting the Supreme Court’s observation in Dutton that “pollution cases may be especially suited to class proceedings” (ibid at 3). The suitability of class actions in environmental matters was viewed positively to the extent that the claim was narrowed to focus on the devaluation of private property to the exclusion of human health–impairment claims. The Court of Appeal explicitly noted that certification was approved as a result of this narrowing, with its observation that “[t]he individual claims of injury to health and related claims would dwarf the resolution of the common issues”; however, “[w]ith the narrowing of the claim that is no longer the case” (ibid at 70). Simply put, the certification battle hinged on the commonality of the issues and whether a class action was a preferable procedure for the resolution of the claim. In fact, the defendant’s argument that individual assessments were needed and that the class action was not a preferable procedure from a judicial economy perspective extended to the devaluation of property values, although the court rejected the argument that even the resolution of the private property claim required individual assessment. As the court pointed out, the claim was staked “on the propositions that public knowledge of nickel contamination in the Port Colborne area has had a detectable impact on property values in that area and that as the source of the contamination, Inco must pay damages to owners whose property values have fallen” (ibid at 70–71). To this end, “[r]esolution of the common issues will determine the question of Inco’s liability for the nickel pollution and whether knowledge of that pollution impacted on property values in the defined area,” and that a “resolution of these issues” is not “negligible in relation to the individual issues” (ibid at 71). Given the reluctance of courts to accept the viability of aggregate assessments of damages to property to date, the decision of the court in Inco to accept such aggregate assessments may be construed as a modest step forward in cases of historical contamination. However, it is abundantly clear that the environmental claim was successful at certification as a consequence of its narrowing to the exclusion of any health-impairment claims.

Despite this privileging of private property over human health (and concerns over the natural environment), the Court of Appeal reconfirmed the normative view that “environmental claims are well suited to class proceedings” (ibid at 88) and repeated the merits of class actions as these pertain to the policy objectives of access to justice and behaviour modification that “[e]nvironmental pollution may have consequences for citizens all over the country” (ibid at 88). Interestingly, although the Court of Appeal confirmed that class actions serve an important purpose in modifying the behaviour of defendants, as well as the behaviour of “other operators of refineries who are able to avoid the full costs and consequences of their polluting activities because the impact is diverse and often has minimal impact on any one individual” (ibid at 88), it nevertheless reiterated that the environmental claim would not have succeeded without being narrowed, effectively allowing the nickel refinery to “avoid the full costs and consequences of [its] polluting activities” (ibid at 88). As discussed below, the implications of this systemic narrowing are potentially far-reaching for Ontario’s class action regime, not exclusively in terms of the secondary policy objective of ensuring deterrence for similarly situated parties, but also in terms of ensuring access to justice in environmental matters, an objective that is not reducible to rights of private property. For the foreseeable future, however, it appears as if health impairment will continue to be systematically excluded from environmental claims as part of legal strategies to attain certification while casting “a very large shadow” over the proceedings, as the “proverbial elephant in the room” (Bowal Reference Bowal2012).

Unlike the majority of certified class actions, Inco did not culminate in a negotiated settlement, but rather advanced to trial on its merits. To date, it is the only environmental class action in common law Canada to proceed to trial on its merits. Notwithstanding this relative victory at certification—“relative” in the sense that certification came at the cost of removing any health-impairing facets from the claim—the claimants in Inco ultimately lost on the merits at trial. Although the trial was initially victorious with a damages award of $36 million—a sum that was calculated based on the speculative devaluation of property values in comparison with a similar residential area—the defendants appealed the case and ultimately won at the Court of Appeal, which overturned the liability and damages assessment. The court concluded that physical changes to a given property do not necessarily constitute physical damages and that “actual, substantial, physical damage” (Smith v Inco [2011]) must be empirically demonstrated.

Perhaps most interestingly, it was the Court of Appeal that initially overturned the denied certification motion on the grounds that the claim no longer included the “sweeping damages” associated with health-impairing events. However, the same court held in the appeal on the merits that the nuisance claim was not constituted because “it was incumbent on the claimants to show that the nickel particles caused actual harm to the health of the claimants or at least posed some realistic risk of actual harm to their health and wellbeing” (ibid at 57). That is to say, the very feature of the claim that allowed it to gain certification—the removal of health impairment—constituted grounds to negate liability upon appeal at trial on the merits. To put it plainly, the claimants could not include health impairment as part of the claim since they would not have attained certification with such a so-called sweeping claim, but at the trial on the merits, the narrowed claim was rejected on the grounds that the claimants could not prove any health-impairing effects from the contamination. According to the court, if “the claimants [had] shown that the nickel levels in the properties posed a risk to health, they would have established that those particles caused actual, substantial, physical damage to their properties” (ibid at 52). The irony is that a claim that includes health impairment is generally incapable of attaining certification, but a narrowed claim that focuses on private property is incapable of proving “actual, substantial, physical damage” (ibid) since such damage is apparently dependent upon proof of health impairment. This circularity suggests that certification will remain a major battleground for environmental class actions, and the ultimate victory of Inco on appeal similarly signals to defendants to start challenging claims more vigorously by refusing to settle post-certification.

Health Impairment at Certification

After Inco, a series of historical contamination cases were certified across Canada by pursuing the strategy of narrowing the scope of the claim to private property harms and excluding health impairment. For example, the Alberta Court of Appeal in Windsor v Canadian Pacific Railway (2007) upheld the certification of an environmental action that alleged that the widespread usage of trichloroethylene by the defendant resulted in the devaluation of property values and concomitant losses in rental incomes as a consequence of toxic contamination of groundwater in a residential area near Calgary. Despite the fact that trichloroethylene is a known carcinogen, the claim in Windsor v Canadian Pacific Railway did not include any health-impairment impacts in order to maximise the likelihood of attaining certification. Such a case is illustrative of a major problem in the way legal strategies have developed: even properties that were extensively rented out to lower-income households—who suffered adverse health effects as a result of their groundwater being contaminated—were covered by the claim, not only as it related to devaluation of property, but also loss of rental income. But the low-income residents of the rental properties were excluded. For such non–property owners, the exclusion of health impairment effectively excluded them from the collective action.

Another landmark case is Ring v Canada, in which the plaintiffs attained certification in Newfoundland in 2007 only to have the certification order overturned in 2010. The class action involved the spraying of herbicides at the Canadian Forces Base at Gagetown from 1956 to the present day and represented all individuals who were exposed to dangerous levels of hexachlorobenzene and dioxin—carcinogenic toxicants that cause lymphoma. The Newfoundland Court of Appeal overturned the certification order on numerous grounds, including the notion that health-impairing environmental claims were not suited to class actions on the grounds that individual assessments needed to be conducted, including toxic causation analyses based upon those individual assessments, while additionally adjudging that the class definition was too broad; once again, the commonality and preferable procedure criteria of certification posed the greatest procedural barriers (in addition to the criterion of an identifiable class). The court’s enumeration of the various obstacles in upholding certification bears examination, given the wider applicability for environmental class actions. It noted that the “toxic level” of “each and every chemical sprayed and every combination of sprays used” would have to be determined, in addition to the length of time in which all the areas could be deemed to be “toxic” (Ring v Canada at 107). The court also noted that there would need to be a firm relation between the toxic levels and the various lymphomas, and an assessment for each claimant with regard to their individual exposures, in addition to the potential for “cumulative effects from multiple visits” (ibid). After describing in great detail the myriad complexities involved in the case, the court observed that given the time frame, the size of the class of potentially affected persons, the size of the base, and the variety of chemicals, “the proposed common issues are insignificant when compared to the large number of individual inquiries” necessary and that “judicial economy, if any, would be minimal” (ibid).

The court’s enumeration of these obstacles sheds light on the interplay between procedural barriers at the certification stage, which sociolegal scholars in the field have hitherto not examined, with the more well-known problems of scientific uncertainty and the dearth of empirical data. The concluding statement also indicates that judicial economy or a lack thereof—as a primary policy objective of class actions alongside access to justice—may be sufficient cause to hinder certifying a class proceeding. This has been confirmed elsewhere, such as the notable Bryson v Canada (AG), a case that arose from the same facts of toxic herbicide usage in Gagetown (certification was denied), where the court observed that “[a]ccess to justice, although one of the most important objectives of class proceedings, is not the only consideration and I am not satisfied that the proposed class proceeding would result in any significant advancement of the goal of judicial economy or that it would provide an efficient and manageable method of resolving the dispute” (Bryson v Canada [Attorney General] at 91).

These obstacles are clearly difficult to surmount. However, an important exception has been identified: environmental claims based on a single event. Such was the case in Durling v Sunrise Propane Energy Group Inc. (2011), which arose out of a series of explosions at a Toronto-based propane facility on 10 August 2008. These propane explosions resulted in damages to approximately 6,386 residents of the affected area, including displacement, inhalation of noxious substances, property damage, fear of life, post-traumatic stress disorder, lost income, and incidental costs. In contrast to the growing tendency in Ontario’s environmental class action regime, Durling v Sunrise Propane was successfully certified. However, this certification motion was largely uncontested by the defendants and a settlement was quickly reached.

Although environmental health claims based on single events more easily pass certification than historical contamination cases, it does not stand to reason that single-event cases are automatically ensured certification. Perhaps more pressingly, it is prudent to note that such single-event cases are relatively uncommon in comparison with historical contamination claims. For the latter, the mounting obstacles to attaining certification are a major source of concern, not merely for the access-to-justice aspirations of class members in the respective claims, but also for the future of health-based claims in environmental class action regimes.

A prominent recent example from Nova Scotia illustrates the various obstacles faced by such actions. The claim in Canada (Attorney General) v MacQueen (2013) involved toxic emissions from a steel production plant in Sydney, Nova Scotia, which the claimants alleged harmed their personal health and private property. The steel plant operated for nearly a century—from 1903 to 2000—in the centre of the city of Sydney, during which time the facility (and the coke ovens associated with steel production) were alleged to have “spewed hundreds of thousands of tonnes of contaminants, including heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and dangerous respirable particles into the air, water, and soil” (ibid 13) of the surrounding region. The Sydney Tar Ponds (as the region is called) has been widely recognized for decades as “one of the most notorious contaminated sites in Canada” (Doelle Reference Doelle2015, 279). Following the strategy of narrowing the claim by excluding health impairment, the claimants sought a series of interrelated remedies, including the “cessation of exposure by either remediation by removal of contaminants from the properties or relocation of residents” (ibid), as well as the “implementation of a medical monitoring program consisting of a large-scale epidemiological study and an education program” (ibid), in addition to damages involving nuisance, trespass, negligence, battery, negligent battery, strict liability, and breach of fiduciary duty (ibid).

Despite the relatively narrow claim, the certification order was overturned at the Court of Appeal on a series of grounds, including that the pleadings alleging nuisance, negligence, and breach of fiduciary duty did not meet the commonality criterion, and that no cause of action was disclosed for the pleadings alleging battery, negligent battery, and strict liability (ibid, 68, 109–10, 151–52, 161). Notably, the court recognized the basic access-to-justice benefits of negative value claims by observing that class member claims “are so small that it would not be worthwhile for them to pursue relief individually and their financial resources are such that they cannot afford to bring separate proceedings” (ibid, 184). However, the court reiterated that the class action was not the preferable procedure on the grounds that the claims were too individualized for a collective legal vehicle. To add another complexity to this already complex type of legal action, the shifting standards of care over time and the reluctance to hold harmful activities from the past to contemporary standards further constrains the possibilities of environmental class actions to address such harms. As Meinhard Doelle has observed, the “devastating effect of this decision on environmental class actions” might effectively “shut the door” on such actions in Nova Scotia (ibid).

There are broader social and political concerns that are raised by recognizing this persistent difficulty of attaining certification for environmental health claims. Judicial preferences for individual resolution to collective health impairments may be indicative of the standpoint that courts do not possess a “role in the regulatory process affecting industrial or landfill pollution or genetically modified plants, for example, which leaves extensive discretion in the legislative and executive branches by virtually eliminating citizen access to courts on these issues” (McLeod-Kilmurray Reference McLeod-Kilmurray2007; Hayes Reference Hayes2009). This judicial preference creates a substantial access-to-justice problem, particularly when public authorities are reluctant to enforce and regulate powerful polluting industries associated with toxic production. More to the point, class action legislation was introduced as a form of privatized regulatory enforcement; indeed, Ian Scott, the Attorney General under whom the CPA was drafted, observed that it was the most important reform of his political career in part because “[t]hrough class actions, the government found a cost-effective way to promote private enforcement and thereby take some pressure off enforcement by the budget-restrained government ministries” (Kalajdzic Reference Kalajdzic2018, 6). The refusal of courts to certify environmental health class actions through the individualization of such claims produces a regulatory enforcement gap for claims based on health-impairing events. To the extent that Canada subscribes to a form of “regulation through litigation,” this enforcement gap is a cause for concern for environmental matters.

Although environmental class actions involving health impairment have proven to be particularly difficult to certify—such cases are perhaps the most challenging in class action regimes across Canada—the obstacles at certification do not exclusively apply to such claims. In fact, attaining certification for environmental class actions across the board has consistently proven to be elusive, even in cases that do not involve health-impairment claims, such as Hoffman v Monsanto Canada Inc. [2007], Roberts v Canadian Pacific Railway Co. [2006], O’Neill & Chiasson v St-Isidore Asphalte Ltée (2013), and Paron v Alberta (Environmental Protection) [2006]. This inhospitable climate for environmental class actions has permeated the legal culture of class action regimes and the gatekeeping criteria of class attorneys. Insofar as the major battleground for class actions remains the certification stage, the persistent difficulties in certifying environmental class actions pose a significant barrier for potential claims-makers and remain a growing cause for concern for the future prospects of multilayer access to environmental justice. The failed outcome of Smith v Inco has exacerbated this inhospitable climate for future claims: “It took 10 years to take the case to trial. The trial itself took months. And the plaintiffs came out of the process with nothing. Against this background, there will undoubtedly be some who will prefer more low-hanging fruit rather than take on the risk of an environmental class action and its unique challenges” (Bowal Reference Bowal2012, 319).

In addition to the devastating loss at trial, Vale (formerly Inco) was awarded adverse costs of over $5 million from Ontario’s Class Proceedings Fund, which had funded and indemnified the class action (this adverse costs award was later reduced to $1.76 million on appeal) (Smith v Inco 2011). This case was extensively cited by the Canadian Environmental Law Association (CELA) in its submission to the LCO, noting its “chilling effect on the willingness of Ontarians to serve as representative plaintiffs in environmental class actions” (CELA 2018, 7). CELA also advocated in favour of reform in Ontario’s costs regime, suggesting a one-way costs rule in which representative plaintiffs may recover costs in case of success without the concomitant risk of paying the defendant’s costs. It bluntly noted that “if Ontario is serious about improving access to environmental justice, then cost reform under the CPA is long overdue” (ibid).

As observed earlier, the recruitment strategies of attorneys have produced an “anaemic class action regime, in which plaintiff’s counsel prefer low-hanging fruit and focus on fairly routine, more or less guaranteed claims” (Jones Reference Jones2013, 370)—in other words, the polar opposite of environmental class actions, whose complex and difficult traits have reinforced this inhospitable climate and entrenched the gap between their original promise and the regrettable reality.

Conclusion

The poor state of environmental class actions in Ontario should not be taken as evidence against their transplantation to other countries, given their many important features that benefit justice seekers and the societies in which they are introduced, including increasing access to justice for both negative and positive value claims, promoting deterrence and behaviour modification in wrongdoers, and preserving judicial resources by aggregating similar claims. Even in areas where class actions are not active, the mere threat of legal action through the vehicle can have beneficial impacts in terms of modifying behaviour and encouraging compliance with rules and regulations. To paraphrase an old sociolegal metaphor, the class action casts a large shadow that can be beneficial for protecting individuals and groups from wrongdoers.

Perhaps more to the point, quite a few of the economic incentives that impede environmental class actions by commercial attorneys do not apply to public interest attorneys and other ideological actors, such as environmental NGOs and other groups whose operations are not strictly determined by market principles and criteria (Goodman and Connelly Reference Goodman and Connelly2018). These legal actors have historically pursued claims on the basis of public interests rather than strictly on economic grounds, which is not to suggest, of course, that the legal opportunity structures in which they operate do not account for economic calculation and strategizing. It is only to observe that the limitations of the entrepreneurialism that otherwise distinguishes class actions does not necessarily dominate their decision-making at case selection and other important junctures. Although economic analyses are relevant throughout a litigation field, these tend to have the greatest explanatory power when applied to commercial rather than public interest lawyering. For the latter, the resource-intensive nature of class actions in both time and capital can nevertheless factor into usage, particularly in jurisdictions such as Ontario, where adverse costs awards loom as a deterrent. Among progressive legal actors, however, class actions are often ultimately welcome additions to a procedural landscape as an important legal means of collective empowerment, access-to-justice promotion, and environmental accountability. This is particularly apparent where regulatory redress is absent and public enforcement is negligible (and especially in cases of regulatory capture by industry), thereby necessitating private forms of enforcement to ensure compliance and compensate victims. This is likely why environmental claims are often cited as suitable for collective redress in states that have incorporated class actions into their procedural landscapes.

As noted at the outset, class actions are an underexplored research topic of Canadian political scientists and sociolegal scholars. Their controversial nature can create a delicate situation for researchers in these fields who examine their merits and limitations as first steps towards reforms that actualize their full access-to-justice potential. Such constructive criticism is distinct from the hostile criticism that can be found in the tort reform movement seeking to restrict, abolish, or reject class actions outright. This article can be viewed as part of the lineage of the former type of scholarship. The poor development of environmental class actions in Ontario should thus be taken as a signal that the state of multilayer access to justice for environmental claims is currently suboptimal and reforms are needed to improve this situation now that it has been identified as such, rather than as an argument against class actions as procedures, tout court.

One possible way forward—apart from the more sweeping political changes needed in environmental governance (such as greater public monitoring and investment in research and data collection)—is to look towards Quebec as an instructive model for future reform; for instance, as noted above, Quebec has a universal funding model and does not have a preferability criterion at authorization or adverse costs awards. Adverse costs, in particular, have a strong deterring effect, and introducing one-way cost shifting in Ontario would be a positive sign that the province wishes to promote greater multilayer access to justice for environmental claims. The chilling effect of Inco would thus likely subside, and the appetite for funding such cases by the Class Proceedings Fund would likely increase. Such outward-looking reforms could extend to changes in the substantive law: notably, the neighbourhood disturbance doctrine in Quebec is a major juridical advantage and has been featured in the majority of environmental class actions advanced in that province. Since the Supreme Court’s decision in St. Lawrence Cement Inc. v Barrette (2008), which established a strict liability regime in Quebec in relation to neighbourhood disturbance, such claims have proliferated (Roberge Reference Roberge2017). Such reforms, however, are likely not forthcoming in the near future, at least not in Ontario. The recent retrenchment initiatives introduced by the Conservative government of Doug Ford that incorporate a predominance requirement into certification, which will likely have the effect of exacerbating the challenge posed by the preferability criterion, indicate that the Conservative government is seeking to restrict class actions rather than facilitate their usage. Certification will now continue to be the major battleground upon which prospective class actions in Ontario are won and lost, and predominance testing will likely increase the latter outcome.

To bring this discussion to a close, it bears noting that I have examined Ontario as a case study chiefly due to its distinction as the major provincial regime for class actions in common law Canada by volume. The shortcomings of this regime, particularly when viewed in comparison with the relative strengths of Quebec’s, leave much to be desired. Although the latter is clearly an outlier in Canada, which reduces its efficacy as a basis for comparative analysis and is one of the reasons why this article has focused on Ontario, it is clear that Quebec offers an example of a regime that is more hospitable to class actions in general and environmental class actions in particular. For now, it may suffice to note the remarkable observation that not only are environmental claims not particularly well suited for class actions in Ontario, they may in fact be particularly ill suited.