INTRODUCTION

Patient engagement in research is defined as research being carried out “with” or “by” patients rather than “to,” “about,” or “for” them. 1 Patients’ personal knowledge and experience of specific research topics have the potential to improve research quality by ensuring that methods are acceptable, that outcomes are patient-centred, and by increasing patient participation.Reference Oliver, Clarke-Jones and Rees 2 Patients can also make research content and language more accessible to patients.Reference Swartz, Callahan and Butz 3 , Reference Nilsen, Myrhaug and Johansen 4 Patient engagement in research is not a new phenomenon. It is rooted in the civil rights movement in the 1960s that led towards more patient empowerment.Reference Kushner 5 In 2011, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) launched its Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR). Researchers applying for funding related to this strategy must demonstrate how patients are an integral part of the research team. 6 In the context of CIHR requirements and increasing positive evidence for patient engagement in research, Canadian emergency medicine (EM) researchers must have access to methods and tools adapted to their context to know how to better engage patients in research.

EM research has contextual factors that make patient engagement challenging.Reference Wright née Blackwell, Blackwell and Carden 7 The short duration of visits and the chaotic conditions prevalent in emergency departments (EDs) make it difficult to recruit and engage patient partners.Reference Wright née Blackwell, Blackwell and Carden 7 The vulnerability of patient groups consulting the ED (e.g., frail elderly, low health literacy) also add an extra challenge to engaging patients as research partners. Interestingly, these are the same reasons why EM research stands to gain from better patient engagement.

Consequently, the Academic Section of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) convened a group of experts, including an experienced patient partner to make pragmatic recommendations on current best practices for the meaningful engagement of patients in EM research in Canada.

METHODS

We used mixed methods consisting of 1) a qualitative narrative review, 2) an online survey, 3) qualitative interviews, and 4) a face-to-face meeting to gather feedback and refine our recommendations.

Literature review

We conducted a narrative review based on the recommendations of the Centre of Excellence for Partnership with Patients and the Public (Montreal, QC). They identified two existing systematic reviews about patient engagement in researchReference Domecq, Prutsky and Elraiyah 8 , Reference Shippee, Garces and Prutsky Lopez 9 and the adapted framework by Wright for patient engagement in EM research.Reference Wright née Blackwell, Blackwell and Carden 7 In addition, we also reviewed all of the referenced papers included in these three publications to determine whether 1) they were relevant to EM, 2) they involved patients recruited from the ED, or 3) their conclusions would help us generate recommendations about patient engagement in EM research. Team members (PMA, KND, SLM, JSL, CV) each reviewed a subset of titles and determined whether a full-text review was needed based on the three inclusion criteria stated previously. For this qualitative narrative review, we did not perform any double extraction or intra-rater reliability testing.

This review allowed us to identify four additional patient engagement frameworks: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), 10 , 11 INVOLVE, 10 National Health and Medical Research Council, 12 and the CIHR SPOR framework. 13 Three authors (PMA, CM, and CV) reviewed these frameworks to identify elements that would guide the structure of our recommendations. After identifying the most relevant papers to review, we conducted a narrative summary of the evidence concerning current best practices, impact, barriers, and facilitators to engage patients in EM research.

Online survey

We adapted a questionnaire developed by Boivin et al.Reference Boivin and Gauvin 14 to question Canadian EM researchers about their experiences and beliefs about patient engagement. Our questionnaire contained 12 items about experience with previous patient engagement activities, types of patients engaged, strategies used to recruit patient partners, roles played by patient partners, impact of patient engagement on previous research activities, unmet needs to support patient engagement, perceived barriers and benefits, and intention for future patient engagement (Appendix 1). These questions were based on the gaps in knowledge that we identified in our literature review. After content and face validity testing within our group and three other EM researchers not involved in this work, we reduced our questionnaire to include 17 items (including 5 sociodemographic questions and 1 question verifying interest in participating in future steps of our project).

We first administered our survey to all of the attendees at the Network of Canadian Emergency Researchers (NCER) meeting held in March 2017. This meeting brought together 26 EM researchers from across Canada. After obtaining consent from all of those present, our questionnaire was completed on site by all of the participants. We then used CAEP’s listserv containing the names of 49 additional EM researchers. The survey was programmed into Survey Monkey and sent out via email, and a single reminder was sent 2 weeks later. Consent to participate was implied by way of completing the survey.

Qualitative interviews

In May 2017, we conducted five interviews with EM researchers from across Canada who had previous experience with patient engagement. These key informants were purposefully selected by an experienced qualitative researcher (KND) from a list of volunteers who had provided their names during our online survey. The interview allowed us to get more in-depth information about what kind of patients to engage, how and when to engage them, and generally what works and what does not work (Appendix 2). The same researcher then performed qualitative content analysis and identified common themes across key informants.

Symposium presentation and feedback analysis

Our panel used an iterative consensus-based approach to formulate a set of preliminary recommendations. We presented our recommendations at the CAEP Academic Symposium held on June 3, 2017. During our presentation, notes were taken about the formulation of our recommendations, and written feedback was collected (Appendix 3). An online feedback form was created to solicit further feedback on each of our preliminary recommendations (Appendix 4). It was distributed using the same listserv used to gather feedback during our online survey and using Twitter to increase the likelihood of receiving feedback. After analysing this feedback, we formulated a final list of recommendations and knowledge gaps to address in future research about patient engagement in EM research.

RESULTS

Literature review

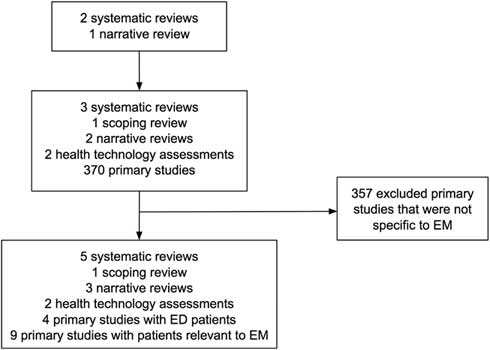

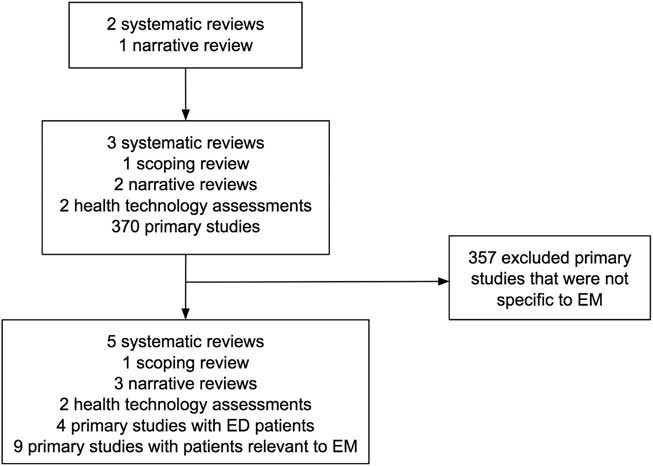

Based on our review of Domecq et al.,Reference Domecq, Prutsky and Elraiyah 8 Shippee et al.,Reference Shippee, Garces and Prutsky Lopez 9 and Wright et al.,Reference Wright née Blackwell, Blackwell and Carden 7 we identified 3 systematic reviews,Reference Nilsen, Myrhaug and Johansen 4 , Reference Brett, Staniszewska and Mockford 15 , Reference Mockford, Staniszewska, Griffiths and Herron-Marx 16 1 scoping review,Reference Stewart, Caird, Oliver and Oliver 17 2 narrative reviews,Reference Boote, Baird and Beecroft 18 , Reference Légaré, Boivin and van der Weijden 19 2 health technology assessments,Reference Oliver, Clarke-Jones and Rees 2 , Reference Hussain-Gambles, Leese and Atkin 20 and 370 primary studies about patient engagement (Figure 1). We found four papers that included patients recruited from the ED 21 - Reference Hirst, Irving and Goodacre 24 and nine papers that included patients with health issues (e.g., coronary artery disease) that could be relevant for EM.Reference Leinisch-Dahlke, Akova-Öztürk and Bertheau 25 - Reference Hanley, Truesdale and King 33 We then summarized our review results into the following themes relevant to EM research: 1) How to identify and engage patients, 2) What can patients do? 3) What are the observed benefits? 4) What are the harms? and 5) What are the barriers?

Figure 1 Flow of studies included in our review.

How to identify and engage patients in EM research

There are no comparative effectiveness studies to support the most effective way of identifying or engaging patients for EM research.Reference Domecq, Prutsky and Elraiyah 8 To engage patients, researchers have used focus groups, interviews, surveys, study boards, and patient advisory councils.Reference Domecq, Prutsky and Elraiyah 8 , Reference Shippee, Garces and Prutsky Lopez 9 , Reference Boote, Baird and Beecroft 18 , Reference Hirst, Irving and Goodacre 24

What can patients do?

Previous EM studies have engaged patients to help with designing the consent process and developing information for patients participating in a trial.Reference Agard 26 , Reference Morris, Nadkarni, Ward and Nelson 34 - Reference Koops 36 Patients have also participated in selecting outcomes, determining the acceptability of data collection procedures, deciding on the ideal time to recruit participants, and deciding when to conduct follow-up.Reference Hussain-Gambles, Leese and Atkin 20 Patients have also suggested changes to study design.Reference Hirst, Irving and Goodacre 24

What are the observed benefits?

We found evidence that patient engagement improves 1) participant enrolment and decreases attrition in studiesReference Domecq, Prutsky and Elraiyah 8 ; 2) selection of patient-centred outcomesReference Domecq, Prutsky and Elraiyah 8 , Reference Stewart, Caird, Oliver and Oliver 17 , Reference Boote, Baird and Beecroft 18 , Reference Leinisch-Dahlke, Akova-Öztürk and Bertheau 25 ; 3) social acceptability of studies with waived or deferred consentReference Nilsen, Myrhaug and Johansen 4 , Reference Morris, Nadkarni, Ward and Nelson 34 - Reference Koops 36 ; 4) design of patient consent materialReference Nilsen, Myrhaug and Johansen 4 , Reference Ali, Roffe and Crome 35 , Reference Koops 36 ; and 5) content and design of knowledge translation material for patients and clinicians.Reference Hess, Hollander and Schaffer 37 , Reference Melnick, Hess and Guo 38

What are the harms?

We found evidence that patient engagement can 1) create frustration with the lengthy process of the research enterpriseReference Brett, Staniszewska and Mockford 15 ; 2) create frustration with tokenistic patient engagementReference Domecq, Prutsky and Elraiyah 8 ; and 3) increase the scope of a project and undesirably change the focus of a project.Reference Domecq, Prutsky and Elraiyah 8

What are the barriers?

The main barriers to engaging patients in EM research are 1) the extra time needed to complete a research projectReference Brett, Staniszewska and Mockford 15 ; 2) the time constraints of patients and researchersReference Brett, Staniszewska and Mockford 15 ; and 3) the lack of funding to support patient engagement.Reference Domecq, Prutsky and Elraiyah 8

Online survey

We sent survey invitations to 75 Canadian EM researchers and received 40 responses (26 NCER attendees and 14 other CAEP EM researchers), which represent a 53% response rate. Our participants were mostly male (75%) and mean (standard deviation) work experience was 14 (12) years. Our respondents came from five provinces across Canada (Table 1). Most respondents (n=33; 83%) intended to engage patients as partners in the next few years. More than half of our participants (58%) had previously engaged patients in EM research: 78% had engaged individual patients; 52% had engaged patient representatives (associations, community organizations); 35% had engaged caregivers; and 17% had engaged other stakeholders (cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR] providers). The activities where patients were engaged and the roles that patients played are presented in Table 1. Almost all respondents (95%) stated that they would need support to engage patients in EM research. Table 1 also presents the type of support that would be needed, the perceived benefits, and the barriers. The different strategies used by Canadian EM researchers to recruit patient partners are found in Appendix 5.

Table 1 Main results from the online survey

Qualitative interviews

All respondents were very positive about including patients in their research going forward but had very little experience. Participants all highlighted the need for help identifying and approaching patients. Other needs were expressed such as 1) guidelines for the conduct of both researchers and patient partners, 2) examples from successful research programs, and 3) training and funding opportunities through groups like CAEP and NCER. Respondents also had concerns and questions about patient engagement such as 1) risk of exposing researchers’ vulnerabilities, 2) project scope creep and change of direction, 3) determining obligations if there is discord, 4) when to use patients given the strong desire to not waste people’s time, and 5) the best patient characteristics (i.e., identifying the level of healthcare knowledge or aptitude that is important, Are patients willing to be educated about the research process? How does one ensure diversity in experience and culture? How does one distinguish between a patient care advocate and a patient research partner?).

Academic Symposium

During the Academic Symposium, two members (PMA and CM) presented a summary of our methodology, results, and a set of preliminary recommendations. These slides are available on Slideshare™ (Sunnyvale, CA, USA).Reference Archambault 39 During the symposium, comments about our recommendations were mainly positive and concerned slight wording changes. We also received online feedback from four emergency physicians and one researcher. Feedback was also mostly positive, and one respondent suggested that we go further in our recommendations. In contrast, disagreement came from one online respondent who stated that funding for patient engagement should be built into public research funding, rather than depend on a national emergency physician specialty society.

DISCUSSION

We grouped recommendations into three categories: 1) general recommendations (Box 1); 2) recommendations about CAEP policy (Box 2); and 3) recommendations for best practices at each phase of a research project (Box 3). For our general and policy-level recommendations, we chose to endorse the CIHR SPOR strategy 40 because of its applicability to the Canadian context and because it could help EM researchers better work in collaboration with the provincial SPOR SUPPORT Units. However, we used the U.S. PCORI frameworkReference Shippee, Garces and Prutsky Lopez 9 to structure and situate our recommendations because it represented well the familiar phases of research where patients could be engaged. Although we have formulated our recommendations based on current evidence, there remain knowledge gaps (Appendix 6) that need more research to inform future revisions of our recommendations.

Box 1. General recommendations

EM researchers in Canada should adopt and endorse the CIHR SPOR strategy for patient engagement in research to:

1. Improve the relevance of their research

2. Improve its translation into policy and practice

3. Contribute to more effective health services and products

4. Improve the quality of life of Canadians and result in a strengthened Canadian healthcare system

Box 2. Recommendations about CAEP policy

In order to foster patient engagement in EM research, CAEP should:

1. Create a National Patient Council as a partnership between a diverse group of patients and EM researchers (Note: Diverse means including members from First Nations, minority communities, vulnerable populations, and a lower literacy population.).

a. Explore a collaboration between organizations such as CAEP and CIHR to support this council.

b. Recruit continuously to support research projects and maintain a broad representation of patients and new ideas.

2. Adopt, adapt, and develop training material, guidelines, and tools for patient engagement for the context of EM research.

a. This would include, for example, how to provide the necessary emotional support for patients and to researchers engaging patients in their research.

b. Create better links and partnerships with provincial SPOR SUPPORT Units who have existing training material, guidelines, and tools for patient engagement.

3. Create a space on the CAEP website to disseminate resources that exist and foster interaction among CAEP EM researchers for patient engagement in research.

4. Make expenses related to engaging patients eligible for CAEP-funded projects.

5. Include patients as reviewers on grant competitions if applicable and relevant.

6. CAEP grant applicants should indicate whether or not and how they engaged patients in their research proposals or their rationale for not doing so.

7. CAEP should consider giving additional merit to projects that engage patients if applicable and relevant.

Box 3. Recommendations for best practices at each phase of a research project

1. Preparatory phase

a. Seek guidance from provincial SPOR SUPPORT Units.

b. Seek guidance about using a framework to help define your approach and situate where patients will be involved in your research (e.g., SPOR, PCORI, INVOLVE).

c. Engage patients as early as possible in designing a research project (e.g., target research questions that align with patient priorities).

d. Establish trust between researcher and patient partners and acknowledge each of their concerns.

e. Plan a budget to recruit patient partners and reimburse their expenses and those of researchers who engage in additional patient engagement activities.

2. Execution phase

a. Patients should be engaged throughout the research execution phase in tasks such as:

i. Deciding on most relevant patient-centred outcomes

ii. Patient recruitment strategies

iii. Guiding the creation of consent forms

vi. Interpreting results

3. Translational phase

a. Encourage and support patients to mobilize knowledge into practice.

b. Work with patients to identify where and how dissemination is most effective for knowledge users (patients, clinicians, policy-makers, and administrators).

c. Work with patients to ensure that language used to communicate results is understandable by knowledge users who will then be empowered to make better decisions.

LIMITATIONS

Our recommendations are limited by the current state of evidence and the complex nature of the intervention.Reference Moore, Audrey and Barker 41 Nevertheless, there is evidence from recent studies in EMReference Hess, Hollander and Schaffer 37 , Reference Melnick, Hess and Guo 38 , Reference Anderson, Montori and Shah 42 , Reference Hess, Wyatt and Kharbanda 43 that engaging patients can lead to the production of more relevant and socially acceptable research. Our recommendations are limited by the design of our literature review. A more in-depth future systematic review will be necessary. Although we did involve an experienced patient partner as a member of our team (CM), we did not interview other patients with experience in EM. Finally, in formulating our recommendations, we did not conduct a formal consensus building process and we did not use a methodology such as GRADEReference Neumann, Santesso and Akl 44 because of time constraints and resource limitations. More work will be needed to engage with Canadian EM researchers, policy-makers and patients to reach a wider consensus and grade the strength of our recommendations.

CONCLUSION

Patient engagement has the potential to improve EM research in Canada by helping researchers select outcomes that matter to patients, increase social acceptability of studies, and design knowledge translation strategies that better target patient’s needs. Our panel made policy-level recommendations to help CAEP support patient engagement in research and pragmatic recommendations to help Canadian EM researchers better engage patients and address some of the barriers to engaging patients in their research.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank CAEP for having financially supported the participation of our patient partner on our panel, which allowed CM to attend and present our panel’s recommendations on June 3, 2017, in Whistler, BC. We also thank Carrie Anna McGinn, Kelly Wyatt, Shanna Scarrow, Cameron Thompson, and Corinne Hohl for their coordination and/or support during this project. Finally, we thank all of the CAEP Academic Section members, Academic Symposium attendees, and online survey participants for their feedback and suggestions about our recommendations.

PMA was the panel lead. He contributed to developing the protocol, extracting data from reviewed literature, collecting data, analysing the results, and drafting the recommendations and the manuscript. He co-presented the panel’s recommendations at CAEP’s Academic Section in Whistler, British Columbia. CM was the patient partner on our panel; she contributed to developing the protocol, collecting data, analysing the results, and drafting the recommendations and the manuscript. She co-presented the panel’s recommendations at CAEP’s Academic Section in Whistler, British Columbia. KND was a panel member; she participated in developing the protocol, extracting data from reviewed literature, conducting the qualitative interviews, analysing the results, drafting the recommendations, and reviewing the manuscript. SLM was a panel member; she participated in developing the protocol, extracting data from reviewed literature, collecting survey results and feedback during the symposium, analysing results, drafting the recommendations, and reviewing the manuscript. CV was a panel member; he participated in developing the protocol, extracting data from reviewed literature, collecting feedback during the symposium, analysing the results, drafting the recommendations, and reviewing the manuscript. JSL was a panel member; he participated in developing the protocol, extracting data from reviewed literature, analysing the results, drafting the recommendations, and reviewing the manuscript. JJP was a panel member and the Academic Symposium Chair; he participated in developing the protocol, drafting the recommendations, and reviewing the manuscript. FPG was a panel member; he participated in developing the protocol and reviewing the manuscript. AB was a panel member; he participated in developing the protocol, analysing the results, drafting the recommendations, and reviewing the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2018.370