Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a core application of emergency medicine training and is now internationally recognized as a diagnostic tool in resuscitation.1–Reference Atkinson, Bowra and Milne2 The 2015 update of the American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) states that POCUS may be used during CPR of cardiac arrest patients, although its usefulness has not been well established.Reference Link, Berkow and Kudenchuk3 Beckett et al. seeks to define more precisely how best POCUS can contribute to the prognosis assessment of patients in cardiopulmonary arrest. The authors evaluated the prognostic value of POCUS in comparison with electrocardiogram (ECG) but also by combining it with the latter when treating patients in cardiopulmonary arrest.

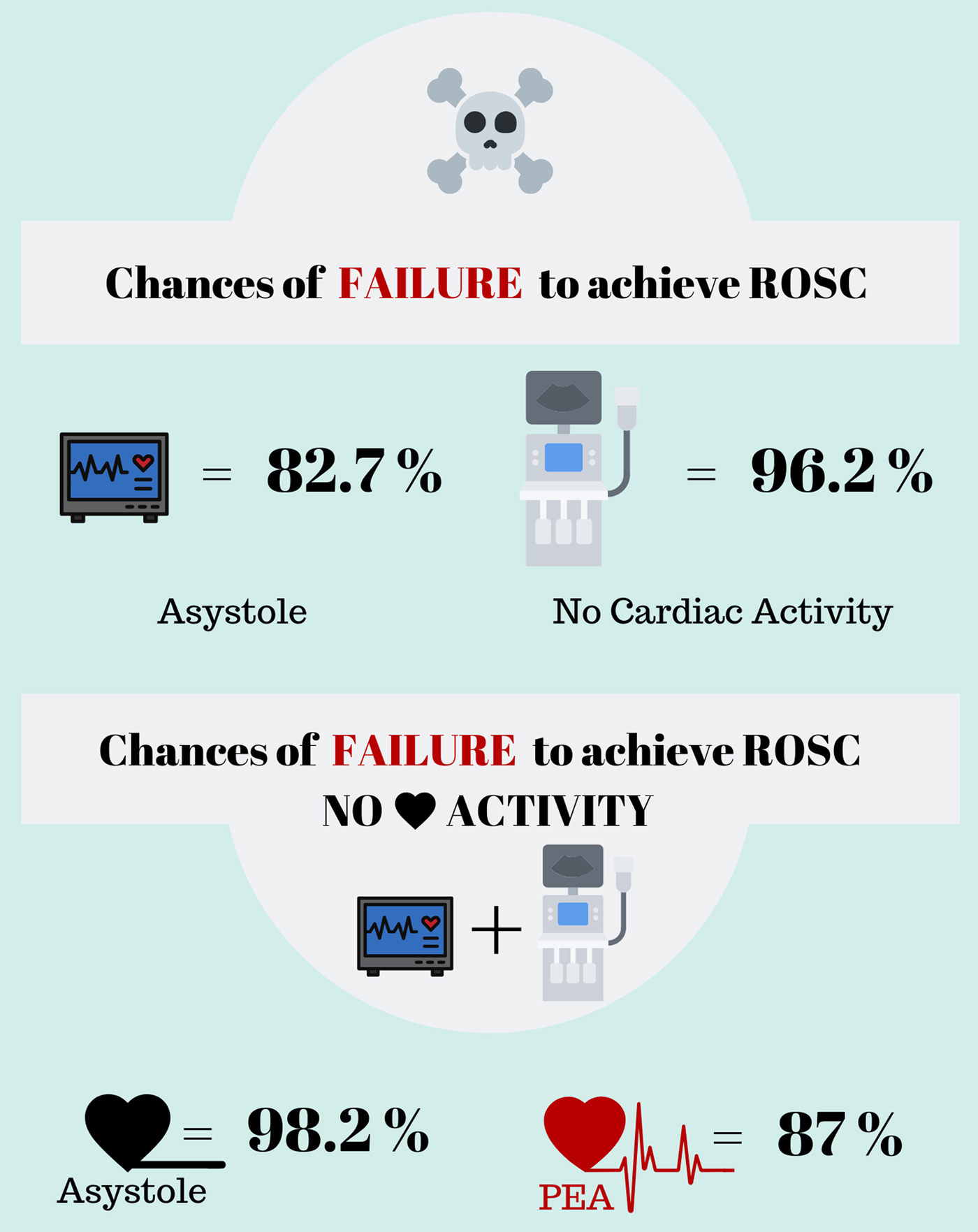

We know that traumatic cardiac arrest differs from atraumatic cardiac arrest in terms of prognosis and etiologies.Reference Soar, Perkins and Abbas4–Reference Hopson, Hirsh and Delgado5 Furthermore, we also know that a much favorable prognosis is associated with shockable rhythms in cardiac arrest compared with non-shockable rhythms.Reference Chan, McNally, Tang and Kellerman6 The fact that the authors precisely defined their population by choosing atraumatic cardiac arrest with non-shockable rhythms allows clinicians to use these results to this specific patient population. Despite the methodological limitations of a health-record review of only 180 cases, the authors are able to add to the body of knowledge regarding prognostication in cardiac arrest. Both ECG and POCUS performed better to predict negative outcomes, death or failure to achieve return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), survival to hospital admission and survival to hospital discharge, compared with positive ones. For ROSC outcome, when using POCUS for patients in cardiac arrest, if there was absence of cardiac activity, there was a 96.2% chance that the resuscitation would be unsuccessful and result in death. When using ECG alone, in patients in asystole, they found a 82.7% chance that the resuscitation would be unsuccessful. When compared, POCUS performed better than ECG as a predictor of death for all three outcomes. However, the more eloquent results were found when combining ECG and POCUS (Figure 1). Authors found a sensitivity of 98.2% for patients who had asystole on ECG and no cardiac activity on POCUS, demonstrating the strength of this combination for this precise subgroup.

Figure 1. Sensitivity of initial electrocardiogram rhythm (ECG), initial point-of-care ultrasound (PoCUS) findings overall, and PoCUS findings in patients with ECG asystole, and pulseless electrical activity, for the predication of no return of spontaneous circulation.

Atkinson et al.Reference Atkinson, Beckett and French7 recently published a study in which authors state that patients with cardiac activity on POCUS had improved clinical outcomes as compared with patients not receiving POCUS and patients with no activity on POCUS. These patients with cardiac activity received longer resuscitation with higher rates of intervention as compared with those without cardiac activity on POCUS or when it was not performed. It will be a challenge to evaluate the favorable outcomes of pulseless electrical activity patients with cardiac activity on POCUS while minimizing the impact of POCUS itself on the results.

POCUS could aid in predicting death among patients with asystole and without cardiac activity while predicting favorable clinical outcomes in the subgroup of patients with pulseless electrical activity and cardiac activity on POCUS.Reference Lalande, Burwash-Brennan and Burns8 The importance of ongoing research cannot be understated because POCUS is potentially not without harm. The 2015 update of the AHA guidelines for CPR and ECC guidelines states specifically that POCUS should not interfere with the standard cardiac arrest treatment protocol.Reference Link, Berkow and Kudenchuk3 A previous study demonstrated delays in CPR when POCUS was used during pulse checks.Reference Huis in't Veld, Allison and Bostick9 Subsequently, another study demonstrated the importance and effective use of a POCUS-integrated cardiac arrest protocol to address delays in CPR with POCUS.Reference Clattenburg, Wroe and Gardner10

Cardiac arrest care continues to evolve and with that the role of POCUS. Surely, with the evidence that exists now, POCUS has a role in predicting death when there is no cardiac activity. However, patients with cardiac arrest are complex, and there is no single best test to determine their prognosis. There still remain many questions to be answered. How should we define cardiac activity on POCUS? When should we perform POCUS when trying to evaluate the prognosis of our patient? Does it matter? What is the best combination of tests we should use to determine a patient prognosis while in cardiac arrest? Beckett's results help us take one step further into answering these important clinical questions. POCUS is essential to the evolution of cardiac arrest care.

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a core application of emergency medicine training and is now internationally recognized as a diagnostic tool in resuscitation.1–Reference Atkinson, Bowra and Milne2 The 2015 update of the American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) states that POCUS may be used during CPR of cardiac arrest patients, although its usefulness has not been well established.Reference Link, Berkow and Kudenchuk3 Beckett et al. seeks to define more precisely how best POCUS can contribute to the prognosis assessment of patients in cardiopulmonary arrest. The authors evaluated the prognostic value of POCUS in comparison with electrocardiogram (ECG) but also by combining it with the latter when treating patients in cardiopulmonary arrest.

We know that traumatic cardiac arrest differs from atraumatic cardiac arrest in terms of prognosis and etiologies.Reference Soar, Perkins and Abbas4–Reference Hopson, Hirsh and Delgado5 Furthermore, we also know that a much favorable prognosis is associated with shockable rhythms in cardiac arrest compared with non-shockable rhythms.Reference Chan, McNally, Tang and Kellerman6 The fact that the authors precisely defined their population by choosing atraumatic cardiac arrest with non-shockable rhythms allows clinicians to use these results to this specific patient population. Despite the methodological limitations of a health-record review of only 180 cases, the authors are able to add to the body of knowledge regarding prognostication in cardiac arrest. Both ECG and POCUS performed better to predict negative outcomes, death or failure to achieve return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), survival to hospital admission and survival to hospital discharge, compared with positive ones. For ROSC outcome, when using POCUS for patients in cardiac arrest, if there was absence of cardiac activity, there was a 96.2% chance that the resuscitation would be unsuccessful and result in death. When using ECG alone, in patients in asystole, they found a 82.7% chance that the resuscitation would be unsuccessful. When compared, POCUS performed better than ECG as a predictor of death for all three outcomes. However, the more eloquent results were found when combining ECG and POCUS (Figure 1). Authors found a sensitivity of 98.2% for patients who had asystole on ECG and no cardiac activity on POCUS, demonstrating the strength of this combination for this precise subgroup.

Figure 1. Sensitivity of initial electrocardiogram rhythm (ECG), initial point-of-care ultrasound (PoCUS) findings overall, and PoCUS findings in patients with ECG asystole, and pulseless electrical activity, for the predication of no return of spontaneous circulation.

Atkinson et al.Reference Atkinson, Beckett and French7 recently published a study in which authors state that patients with cardiac activity on POCUS had improved clinical outcomes as compared with patients not receiving POCUS and patients with no activity on POCUS. These patients with cardiac activity received longer resuscitation with higher rates of intervention as compared with those without cardiac activity on POCUS or when it was not performed. It will be a challenge to evaluate the favorable outcomes of pulseless electrical activity patients with cardiac activity on POCUS while minimizing the impact of POCUS itself on the results.

POCUS could aid in predicting death among patients with asystole and without cardiac activity while predicting favorable clinical outcomes in the subgroup of patients with pulseless electrical activity and cardiac activity on POCUS.Reference Lalande, Burwash-Brennan and Burns8 The importance of ongoing research cannot be understated because POCUS is potentially not without harm. The 2015 update of the AHA guidelines for CPR and ECC guidelines states specifically that POCUS should not interfere with the standard cardiac arrest treatment protocol.Reference Link, Berkow and Kudenchuk3 A previous study demonstrated delays in CPR when POCUS was used during pulse checks.Reference Huis in't Veld, Allison and Bostick9 Subsequently, another study demonstrated the importance and effective use of a POCUS-integrated cardiac arrest protocol to address delays in CPR with POCUS.Reference Clattenburg, Wroe and Gardner10

Cardiac arrest care continues to evolve and with that the role of POCUS. Surely, with the evidence that exists now, POCUS has a role in predicting death when there is no cardiac activity. However, patients with cardiac arrest are complex, and there is no single best test to determine their prognosis. There still remain many questions to be answered. How should we define cardiac activity on POCUS? When should we perform POCUS when trying to evaluate the prognosis of our patient? Does it matter? What is the best combination of tests we should use to determine a patient prognosis while in cardiac arrest? Beckett's results help us take one step further into answering these important clinical questions. POCUS is essential to the evolution of cardiac arrest care.

Competing interests

None declared.