Introduction

It has long been recognized that outcome feedback has an important role in physician education and clinical expertise development. Patient follow-up has been described as necessary for physicians to confirm or critique their decision-making processes, a unique challenge within the specialty of emergency medicine (EM).Reference Croskerry 1 A recent systematic review defined outcome feedback as “the natural process of finding out what happens to one’s patients after their evaluation and treatment in the emergency department.”Reference Lavoie, Schachter, Stewart and McGowan 2 This review attempted to elucidate current knowledge regarding outcome feedback, as well as its impact, incidence, and modifiers. While seven reports were identified, all were deemed to be of inadequate quality to make definitive recommendations on anything beyond future directions for research.Reference Lavoie, Schachter, Stewart and McGowan 2

At the current time, there are no clearly established guidelines by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) or the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada that delineate what, if any, outcome feedback systems should be in place in EM residencies. While no guidelines have been published, reflective practice and patient follow-up are endorsed by the ACGME, American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) and others. 3 – 5

The objective of this study was to describe the current prevalence of active outcome feedback and follow-up within adult and pediatric EM training programs, and to characterize the perceived educational value by residents and program directors.

Methods

Study design and population

A national survey of residents enrolled in Royal College-accredited adult EM and pediatric EM programs in Canada, and their respective program directors, was conducted. The Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board approved the study protocol (2011488-01H). Completion and return of the survey implied consent without specific need to obtain it in writing. After review of the literature and consultation with experts in the field, a survey tool was developed for EM program directors, and a second for EM residents. These surveys contained items regarding outcome feedback systems, educational values, legal barriers, and demographics. The instruments were piloted with a group of six Canadian College of Family Physicians (CCFP) EM residents and one program director for readability, layout, timing, relevance, and content with amendments incorporated into the final draft (Appendix A and B). Definitions of terms used in the survey are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1 Outcome feedback definitions

The total eligible survey population was calculated with the assistance of the Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS) and each individual academic program. 6 In August 2011, there were 14 Royal College-accredited adult EM programs with 323 active EM residents. There were also 10 pediatric EM programs with 46 active residents. All 24 Royal College adult EM and pediatric EM program directors were contacted and surveyed. The final eligible resident sample size was defined as the number of residents present on the day of survey administration. For this reason, upon distribution of the tool, chief residents were asked to determine resident attendance so that response rates could be calculated.

Survey content and administration

Resident surveys

A list of chief residents was obtained from the administrative staff of their respective programs. Once contacted by email, the chiefs were informed of study details and asked to assist in distributing paper surveys to all residents during a mandatory academic activity. Surveys were distributed to residents in this way, as a recent study had achieved excellent response rates utilizing this same method.Reference Wang, Frank and Lee 7 Upon survey completion, residents returned their surveys to the chief in a sealed envelope that was then couriered back to the principal investigator at the University of Ottawa in a pre-paid, pre-addressed envelope. These surveys were coded with a unique numeric identifier to link them to each program. Unique identifiers were only known to those involved in the study to ensure confidentiality for all participants. Survey data were abstracted and entered into a Microsoft® Excel (Version 14.2.0 Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) database for further analysis.

Program director surveys

A list of program directors was obtained from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada website. 8 , 9 All program directors were contacted by email with a standardized letter that provided relevant background information, study purpose, confidentiality information, and an individualized link to an electronic SurveyMonkey® collection tool. 10 All surveys were coded with a unique numeric identifier. No personal identifying data were collected on the surveys. Reminder emails were distributed to all those that did not respond at two, four and six weeks in order to increase response rates.Reference Dillman, Smyth and Christian 11 If at this time there was still no response, available associate program directors were contacted. In a final attempt to optimize response rates, non-responders were contacted by telephone to ensure survey receipt and address any concerns.

Data analysis

Using SAS®. Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), the response rate was calculated, using the total number of individuals exposed to the survey as the denominator, and the total number of surveys returned as the numerator. Normally distributed continuous variables were described with means and standard deviations, while skewed continuous variables were described by medians and range. Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed with proportions. Two independent reviewers (TD, JW) categorized open free-text responses, and these data were presented according to theme. Correlations between resident and program director responses were sought in predefined variables, including rates of mandatory follow-up, impact of outcome feedback and perceived educational benefit/harm. The p values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Between April and November 2012, surveys were distributed to a total of 260 residents (237 adult EM residents; 23 pediatric EM residents), of whom 210 responded (80.8%) (187 adult EM; 23 pediatric EM). Two adult EM surveys were removed prior to final analysis because responses indicated that they had been intentionally spoiled. Resident respondents included those from 14/14 adult EM programs and 6/10 pediatric EM programs. (Baseline resident demographics can be found in Table 2.) Program directors responded from 21/24 programs (14/14 adult EM; 7/10 pediatric EM) for a response rate of 87.5%. These individuals represented a range of program sizes (from 3 to 35 residents) and experience levels (program director for 1 to 16 years).

Table 2 Demographics and Baseline Characteristics of Resident Respondents (N=210)

* Unless otherwise indicated

† Postgraduate year 6 respondents were all in the pediatric EM program

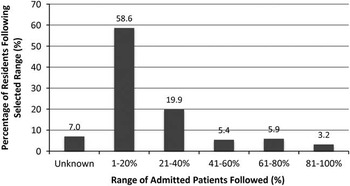

No Canadian program required residents to seek active outcome feedback on patients who were seen in the emergency department (ED) and subsequently admitted or discharged home (0/21 program directors). This was consistent with results submitted by residents. Independently, 89.4% (186/208) of residents reported that they followed-up on a portion of patients admitted through the ED. Nearly half of the residents surveyed, 44.2% (92/208), performed follow-up on patients who were seen in the ED and discharged home. The proportion of patients followed was distributed across a wide range (Figures 1 and 2). When asked, 76.9% (160/208) of residents felt that patient follow-up should be considered mandatory within their residency education, in contrast to 42.9% (9/21) of program directors (p=0.002).

Figure 1 Proportion of Admitted Patients Followed by Residents (N=186).

Figure 2 Proportion of Disharged Patients Followed by Resident (N=92).

Respondents were asked to rank the perceived educational value of outcome feedback on a 7-point Likert scale. A score of 1 indicated “not important,” 4 “neutral,” and 7 “very important.” The resident mean score was 5.8, compared to the program director mean of 5.1 (difference 0.7; p=0.002). A majority (85.1%, 177/208) of residents felt that outcome feedback was more valuable in certain patients. Of these residents, most indicated that patients presenting with a critical illness (28.8%, 51/177) and those with diagnostic uncertainty (61.6%, 109/177) yielded the highest educational value.

Of the residents contacted, 72.1% (150/208) assigned a score of 3 or less (Likert mean 2.80, where 1 indicated “not satisfied,” 4 “neutral” and 7 “satisfied”) for their satisfaction with the level of outcome feedback received. Residents and program directors were asked whether passive outcome feedback (i.e., discharge summaries, consultant notes) was provided to residents directly. While 3/21 program directors indicated that this practice was in place, residents from only a single program (1/20) agreed. Furthermore, only two programs had a system in place to alert residents when a patient they had recently treated in the ED returned within a predefined period of time.

Questions listed in both the resident and program director surveys explored the perceived effect of outcome feedback on diagnostic accuracy, job satisfaction, treatment outcomes and clinical efficiency. A majority (92.7%, 191/206) of residents believed that increased outcome feedback would improve diagnostic accuracy, as compared to 65.0% (13/20) of program directors (p=0.001). Similarly, 80.1% (165/206) of residents felt that outcome feedback improved job satisfaction, as compared to 60.0% (12/20) of program directors (p=0.04), and 90.3% (186/206) of residents believed it improved treatment outcomes, as compared to 65.0% (13/20) of program directors (p=0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in projected clinical efficiency in the context of improved outcome feedback (73.3%, (151/206) residents, 55.0 % (11/20) of program directors; p=0.08), although there was a trend.

Discussion

The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada does not mandate that residents in an EM program follow-up on patients treated in the ED. 5 The Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the Residency Review Committee for Emergency Medicine (RRC-EM) in the United States had stipulated, from 1980 until 2010, that all American residency programs have an outcome feedback system in place for patients seen in the ED by residents. 12 Despite this requirement, many residency programs across the United States consistently failed to achieve this standard.Reference Gaeta and Osborn 13 – Reference Osborn and Negron 15 The practice of patient follow-up has been more recently endorsed in a 2012 publication jointly written by the ACGME and ABEM that defines the suggested progression of competencies within an EM training program. 3

The extent to which outcome feedback and follow-up is currently taking place in Canadian EM training programs has not been previously studied. In the most recent evidence from the United States, a group of researchers surveyed all American program directors in 1984, 1988, 1992, and 1996 to determine the levels of compliance with the RRC-EM requirements.Reference Gaeta and Osborn 13 In 1996, 74% (75/101) of programs had a follow-up system in place for admitted patients, and 51% (52/101) for patients discharged home.Reference Gaeta and Osborn 13 The extent of patient follow-up that has been occurring more recently is not known. There is currently no literature that describes the proportion of residents who perform voluntary follow-up or what proportion of patients is followed. Additionally, very little has been published regarding the prevalence of passive outcome feedback within EM, but evidence suggests that it is low for both residents and staff physicians.Reference Adams and Keller 16 , Reference Lavoie, Plint and Clifford 17 The study survey results reveal that there is currently no mandated follow-up of emergency department patients in residency programs; however, a majority of trainees voluntarily followed between 1–20% of patients that they had treated. Passive outcome feedback was rare, only being corroborated by residents in a single program. Lavoie et al suggested that greater feedback for staff emergency physicians could improve job satisfaction, clinical efficiency, diagnostic accuracy and treatment outcomes.Reference Lavoie, Plint and Clifford 17 This belief was supported by the majority of residents and program directors in this study.

Two small studies have examined the perceived educational value of outcome feedback in the ED in the United States. An abstract published in 1992 by Adams and Keller stated that 93% of all EM chief residents surveyed agreed that feedback was important and greater feedback would improve education.Reference Adams and Keller 16 Interestingly, only 33% were currently satisfied with the amount of feedback they were receiving from admitting services.Reference Adams and Keller 16 The second study by Sadosty et al in 2004 found that in a program evaluating the educational value of patient follow-up in the emergency department, 81.3% of cases reviewed by residents were believed to be educational.Reference Sadosty, Stead and Boie 18 In the current study, it was found that residents perceived feedback as significantly more educationally valuable than their program directors, and 72.1% indicated they were less than satisfied with the amount of outcome feedback they received. The difference in perceived educational value between residents and program directors is hypothesized to be due a resident deficiency in clinical experience that elevates the perceived value of feedback above that of more seasoned program directors. This raises the question of whether EM training programs are missing a valuable educational opportunity.

While there exists little empiric research documenting the perceived educational value or subsequent patient care impact of outcome feedback, there is a body of literature exploring the theory of deliberate practice and how feedback may contribute to the process of becoming a medical expert. A physician who has been identified as an expert in their field has demonstrated “their superior performance on representative tasks that capture the essence of expertise in the domain.”Reference Ericsson 19 The theory of deliberate practice is a construct that attempts to explain the etiology of variability between levels of expert performance within a profession.Reference Ericsson 19 Deliberate practice itself involves the rehearsal of specific activities that are designed to elevate one’s current level of performance, is effortful, and requires time and energy.Reference Ericsson, Krampe and Tesch-Romer 20 Ericsson states, “Acquisition of expert performance requires engagement in deliberate practice.”Reference Ericsson 19 He concludes, “without valid informative feedback on their performance, it would be difficult for experts to engage in deliberate practice in order to enhance their skills.”Reference Ericsson 19 Outcome feedback in EM residencies represents a source of self-evaluative feedback that can be directly applied to deliberate practice within a trainee’s educational curriculum. Ericsson’s work supports the hypothesis that greater outcome feedback during residency can enhance an individual’s ability to acquire a superior level of performance.Reference Ericsson 19 Mandatory deliberate practice and outcome feedback may therefore result in improved resident performance if it is used within EM training programs.

Limitations

This survey was conducted within the Canadian EM training community, which contains a relatively small number of program directors. As a result, the aggregate results remain heavily influenced by each director’s individual responses. This should be considered when comparing the results of residents to those of the program directors. As a Canadian EM sample was used, results may not be representative of programs in other countries.

Data were collected using a novel survey tool designed specifically for this study. While the tool was developed by educational experts and piloted on a population of residents and program directors, it is important to recognize that the survey has not been otherwise validated. In addition, due to the nature of the study topic, there remains a possibility of social desirability bias within responses.

Finally, in the results section, it was stated that there was a statistically significant difference between the perceived educational value of feedback between residents and program directors. While this was true, the absolute difference between the resident mean (5.8) and the program director mean (5.1) was 0.7. The educational significance of this value is subjective. It is possible that a larger program director sample could assist in demonstrating a larger absolute difference.

Future directions

The results that have been generated from this study stimulate future lines of investigation in three directions. The first is to replicate and compare findings in American EM training populations to demonstrate the generalizability of future interventions and results. This work may also look to further characterize what information and what patient population is most valuable in the feedback process.

Subsequently, the focus will be on the development of a pilot electronic system that provides educationally valuable targeted feedback. With near universal implementation of electronic patient tracking systems, it should be possible to notify residents when patients return to any ED. Similarly, with electronic health records, passive outcome feedback could be easily improved by forwarding electronic correspondence to not only the attending emergency physician but also the treating emergency resident. Being provided with this additional information would allow residents to critically appraise their clinical treatment and decisions and incorporate this knowledge into their future practice.

Finally, it would be important for future research to demonstrate a relationship between outcome feedback and an educationally meaningful outcome, such as resident knowledge or its surrogate marker. This information would further legitimize the importance of this practice within EM training programs.

Conclusions

This study of EM residents and program directors is the first to describe an absence of mandatory patient active outcome feedback but a high prevalence of self-directed patient follow-up. It also found that EM residents perceived outcome feedback as significantly more educationally valuable than their program directors. While the majority of residents, and the theory of deliberate practice, supported some form of mandatory patient follow-up, future research will need to explore the optimal design, implementation, and monitoring of such a system. In addition, it will be important to describe the most valuable patient population in which outcome feedback should be achieved, and determine whether such feedback results in clinically or educationally significant outcomes. Given the discovered educational gap and opportunity for improved resident training, all EM programs should consider incorporating outcome feedback and follow-up.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Laura Carr, Cathryn Peloso, and Ria Cagaanan for your administrative support, Angela Marcantonio for your assistance with research ethics and abstract presentation preparation, Jonathan Dupre for managing the online survey software, and My-Linh Tran for your statistical analysis and expertise.

Competing Interests: Funding was provided by the Department of Emergency Medicine Research Grant (University of Ottawa) and CAEP (Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians) Research Grant. This research was originally presented at The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Conference (May 15,2013), in Atlanta, GA, USA, as well as the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) Conference (June 2, 2013), in Vancouver, AB, Canada.

Supplementary Materials

To view Supplementary Materials for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cem.2014.47