INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is the leading risk factor for death worldwide and leads to significant morbidity and mortality secondary to conditions such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and renal failure. 1 In Canada, almost a quarter of the adult population has hypertension;Reference Robitaille, Dai and Waters 2 worldwide, it affects one billion individuals.Reference Chobanian, Bakris and Black 3 Given the increasing prevalence of hypertension,Reference Levy and Cline 4 it follows that visits to the emergency department (ED) for hypertension and its sequellae can also be expected to increase.Reference Nawar, Niska and Xu 5 , Reference Fields, Burt and Cutler 6 The aging populationReference Fields, Burt and Cutler 6 and increased use of home blood pressure (BP) measuring devicesReference Mancia, Fagard and Narkiewicz 7 will likely further impact ED visits for hypertension in the coming decades.

For patients with hypertension but without a hypertensive emergency, there is an absence of evidence to guide ED management.Reference Wolf, Lo and Shih 8 We suspect that this results in wide practice variation amongst emergency physicians. Whether or not emergency physicians routinely offer new antihypertensive prescriptions (or increase the dose of pre-existing prescriptions) is unknown, as is the timeframe within which they advise patients to obtain follow-up care. Most of the existing emergency medicine literature on this topic has extrapolated from primary care guidelines to the ED setting.Reference Wolf, Lo and Shih 8 , Reference Hackam, Quinn and Ravani 9 The 2006 American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) policy statement indicates that patients with asymptomatic hypertension require “prompt... follow up with their primary physician;” however, a specific timeframe was absent.Reference Decker, Godwin and Hess 10

In the absence of evidence, the practice of one’s peers forms a de facto standard. The purpose of our study was two-fold: (1) to establish whether there is a threshold BP at which emergency physicians will initiate or modify antihypertensive medications; and (2) to determine the follow-up interval recommended by emergency physicians for patients discharged from the ED with asymptomatic elevated blood pressure.

METHODS

Study design

We performed a cross-sectional survey of emergency physicians attending rounds at seven sites in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), or Emergency Medicine Grand Rounds for the University of Toronto, in September and October 2013. Research Ethics Board approval was obtained from the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Setting and participants

The GTA has a catchment area of approximately six million people 11 served by five tertiary and 13 community EDs (excluding specialty EDs). Nearly all sites have at least monthly ED rounds; a convenience sample of seven sites was selected (Table 1) with the aim of having a roughly equal number of tertiary and community EDs. Participants had to be certified emergency physicians, either through the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) or the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC). In-person recruitment at ED rounds was specifically utilized to avoid the poor response rates typical with electronic surveys.Reference Hollowell, Patel and Bales 12 , Reference VanDenKerkhof, Parlow and Goldstein 13

Table 1 Participant characteristics.

SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; CCFP: Canadian College of Family Physicians; EM: emergency medicine; FRCPC: Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada; MD: medical doctor

* small cell size, <5, cannot be reported for privacy reasons

Methods of measurement

The principal investigator (DDC) attended each rounds, provided a standardized verbal summary of the rationale of the study to all attendees, and then distributed the surveys to individuals who self-identified as certified emergency physicians. It was emphasized that the study aimed to determine usual practice rather than perceived “ideal practice.” No further guidance about survey content was provided.

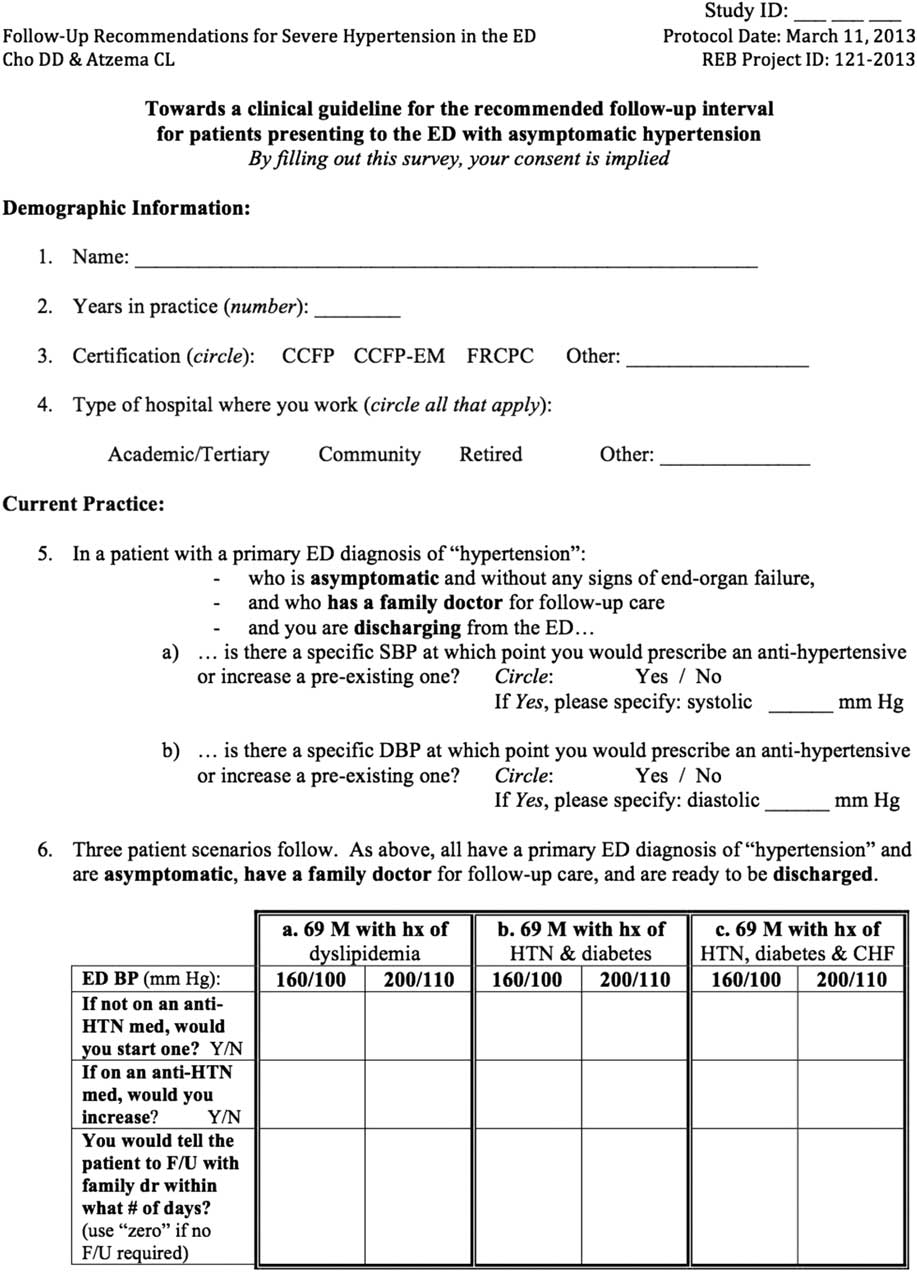

The one-page survey included physician demographic information, eight general questions regarding BP thresholds, and a series of specific questions surrounding six related clinical vignettes (Figure 1). Both general questions and clinical vignettes were employed to serve as different approaches to answer the research questions, in the event that participants answered differently when presented with a specific clinical case. Each patient presented in the vignettes had a final ED diagnosis of hypertension and was deemed fit for discharge by the managing emergency physician after a work-up revealed no end-organ damage, and was assumed to have a primary care physician with whom they could follow up. 14 Blood pressures of 160/100 mm Hg (the threshold for stage 2 hypertension) and 200/110 mm Hg were chosen for the vignettes to provide extremes that would help determine whether the degree of hypertension modified decision-making.Reference Chobanian, Bakris and Black 3 , Reference Mancia, Fagard and Narkiewicz 7 The survey was pilot-tested on 10 emergency physicians and adjusted as necessary.

Figure 1 Survey instrument.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the proportion of physicians who reported having a threshold systolic and/or diastolic BP at which they would prescribe a new antihypertensive or increase the dose of a pre-existing antihypertensive. For those who reported a threshold, specific BP values were elicited. Secondary outcome measures included: (1) the association of patient-level factors (BP values and number of relevant comorbidities) and provider-level factors (years in practice, practice certification, and hospital type) on antihypertensive prescription provision; and (2) the number of days emergency physicians recommended for follow-up with a primary care physician.

Primary data analysis

Responses were entered into an Excel file (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) with double data entry on 100% of the responses. Range and logic checks were performed and descriptive statistics were generated. To examine which variables were associated with offering or increasing an antihypertensive prescription, logistic regression modeling was utilized using generalized estimating equations to account for clustering on physician (since the same physician responds to all questions in a single survey). Patient-level factors and emergency physician factors were regressed on new antihypertensive prescription provision in the first model and on an increased dose in the second. To evaluate whether physicians actually practiced as they indicated in the survey, we performed a post-hoc analysis on an existing dataset (collected via chart review)Reference Gilbert, Lowenstein and Koziol-McLain 15 of discharged patients with a primary diagnosis of hypertension from two study sites in fiscal year 2010. Data were analyzed using SAS software (Version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Surveys were offered to 81 eligible emergency physicians from seven hospital sites. The response rate was 100%, missing data was <1%, and double-data entry had extremely high agreement (κ=0.94-1.00 for all variables). Characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1.

Blood pressure thresholds

In all, 51.9% (95% CI, 40.5-63.1) of participants reported having a specific systolic BP threshold that would trigger them to write a prescription for a new antihypertensive and 48.1% (95% CI, 36.9-59.5) reported having a systolic BP threshold for increasing the dose of a pre-existing antihypertensive. Of those who would offer a new antihypertensive prescription or increase a pre-existing prescription, the median threshold values were both 200 mm Hg (IQR 180-210 and 180-200, respectively).

In all, 55.6% (95% CI, 44.1-66.6) of participants reported having a diastolic threshold that would trigger a new antihypertensive prescription and 49.5% (95% CI, 38.1-60.7) reported a threshold for increasing the dose of a pre-existing prescription. The median diastolic threshold values reported by participants who would offer a new antihypertensive prescription or increase a pre-existing prescription were both 110 mm Hg (IQR 110-120 and 100-120, respectively).

In response to the clinical vignettes, 5% of participants reported that they would offer a new prescription for a 69-year-old male with dyslipidemia and a BP of 160/100 mm Hg (Table 2). Adding a history of hypertension and diabetes more than doubled the proportion of participants indicating they would initiate antihypertensive medication, while an additional history of heart failure increased the proportion almost six-fold to 27.8%. In comparison, when presented with a patient with dyslipidemia and a BP of 200/110 mm Hg, 61.0% of participants indicated they would offer an antihypertensive prescription. Adding a history of hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure resulted in 70.5% reporting that they would offer a new antihypertensive prescription. Results for increasing the dose of a pre-existing antihypertensive were similar (Table 2).

Table 2 The effect of degree of blood pressure level and patient co-morbidities on emergency department antihypertensive prescriptions.

HTN: hypertension; CHF: congestive heart failure; ED: emergency department; BP: blood pressure; SD: standard deviation

Adjusted predictors of antihypertensive prescription provision

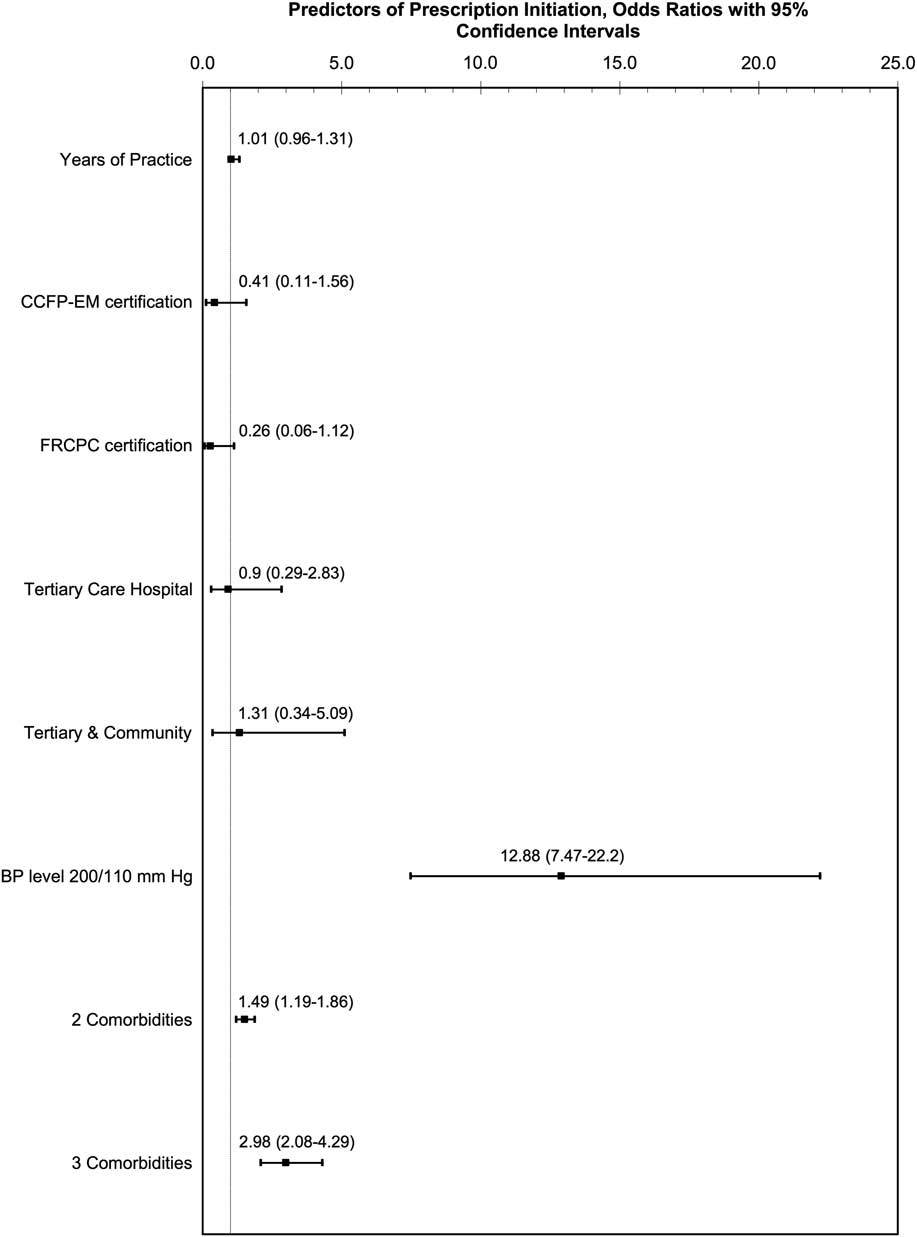

In the model of offering a new antihypertensive prescription, patient-level characteristics were found to be independently associated with a new prescription: a BP of 200/110 mm Hg was associated with markedly increased odds (OR 12.9; p<0.001), compared to 160/100 mm Hg (Figure 2). A patient with three comorbidities also had substantially increased odds (OR 2.98; p<0.001), relative to the patient with one comorbidity. Emergency physician factors were not found to be associated with antihypertensive prescription provision. Similarly, in the model of increasing a pre-existing prescription, two patient characteristics (higher BP level [OR 15.2; p<0.001] and three comorbidities [OR 2.3; p<0.001]) were found to be independently associated with the outcome of interest, while emergency physician characteristics were not.

Figure 2 Logistic regression modeling of initiation of a new antihypertensive prescription, using GEEs to account for clustering on physician.

Follow-up recommendations

Follow-up recommendations were found to vary by BP value, and to a lesser extent, by patient comorbidity. At 160/100 mm Hg, participants recommended follow-up within a mean of 7, 6, and 5.5 days of ED discharge for a patient with a history of dyslipidemia, hypertension and diabetes, and the further addition of heart failure, respectively. The follow-up recommendation interval was shorter in the scenario with BP 200/110 mm Hg (Table 2).

Post-hoc analysis

Among the participants at the two study sites where chart review was undertaken, 11% and 71% reported they would provide a new antihypertensive prescription at 160/100 and 200/110 mm Hg, respectively, for a patient with hypertension and diabetes (two comorbidities). In comparison, the median triage BP of patients seen at these sites from chart review was 183/99 mm Hg (IQR 165-198/86-110), and 57.9% (95% CI, 53.3-62.5) were provided with a new antihypertensive prescription or increased dose. Among patients with only two comorbidities (data on heart failure was not available), the median triage BP was 187/91 mm Hg and 63.0% (95% CI, 54.9-74.0) had documentation of an antihypertensive prescription being provided. Follow-up instructions were documented on the chart in 89.6% (95% CI, 86.4-92.2) of charts.

DISCUSSION

In this study of community and academic emergency physicians attending rounds, only half reported having a “threshold” BP level that would prompt them to provide a prescription for a new antihypertensive medication or increase the dose of a pre-existing antihypertensive medication, in patients being sent home with a primary ED diagnosis of hypertension. This likely reflects the lack of evidence in the ED setting on which to base management decisions,Reference Decker, Godwin and Hess 10 and underscores the lack of consistency that currently characterizes the care of these patients in the ED.

When presented with a specific case, however, the majority of participants reported a willingness to initiate an antihypertensive: for a patient with a BP of 200/110 mm Hg and three cardiac comorbidities, 71% reported that they would offer an antihypertensive prescription. This might be viewed as a disparity in responses, which could be secondary to a lack of understanding of the initial, more hypothetical, question, or it may arise from the fact that the approach changes depending on the clinical situation (which included an older patient with three comorbidities). While most emergency physicians indicated that they would initiate an antihypertensive medication in certain hypertensive patients, almost a third indicated they would not, even at a very high BP level and in the context of multiple patient comorbidities.

Which approach is better for the patient is unknown, as long-term outcomes after an ED visit for hypertension have received very limited study. The JNC 7 (7th report of the Joint National Committee) recommends against the routine initiation of medications in the ED,Reference Chobanian, Bakris and Black 3 although similar recommendations were absent from JNC 8.Reference James, Oparil and Carter 16 The current ACEP (American College of Emergency Physicians) guidelines are concordant with the JNC 7, with the caveat that they deemed treatment could be warranted in certain patient populations, such as those with poor follow-up care.Reference Wolf, Lo and Shih 8 A 1967 study found that among 143 discharged men with a diastolic BP between 115 and 130 mm Hg, those who were not given an antihypertensive prescription had an adverse event rate 6% higher at 4 months and 36% higher at 20 months, compared to those who were provided a prescription. 17 However, the confidence intervals of this finding were wide and the data are not current. A more recent 1999 study of 74 discharged ED patients at a teaching hospital who presented with a systolic or diastolic BP of at least 220 or 110 mm Hg, respectively, found that 13.5% of participants returned to the ED within three months with significant cardiovascular complications.Reference Preston, Baltodano and Cienki 18 Several studies have assessed short-term outcomesReference Grassi, O'Flaherty and Pellizzari 19 , Reference Frei, Burmeister and Coil 20 and found very low frequencies of poor outcomes; however, hypertension is a disease that has significant long-term, rather than short-term, impact.Reference Chobanian, Bakris and Black 3 Large studies on the long-term outcomes are needed in order to guide these management decisions and, in turn, provide consistency of care to such patients across physicians.

While 70% of emergency physicians in our study reported that they would offer an antihypertensive prescription at a certain BP and comorbidity level, a retrospective study at a teaching site found that, of those patients recognized to have incidental asymptomatic elevated BP, only 2.4% were discharged home with an antihypertensive prescription.Reference Tilman, DeLashaw and Lowe 21 However, that study included all-comers to the ED and did not assess average BP values or patient comorbidities. Another study that screened all ED patients for hypertension reported that 8.5% of patients were offered an antihypertensive prescription if their BP was 160 systolic or 100 diastolic mm Hg,Reference Baumann, Cline and Cienki 22 a finding similar to our study where 5% of participants offered an antihypertensive prescription at 160/100 mm Hg.

Provider characteristics have been found to be more strongly associated than patient characteristics with the investigation and management of atrial fibrillation,Reference Rosen, Davis and Lesky 23 , Reference Stiell, Clement and Brison 24 myocardial infarction,Reference Tu, Austin and Chan 25 , Reference Rathore, Chen and Wang 26 and other conditionsReference Berthold, Gouni-Berthold and Bestehorn 27 . In contrast, our findings suggest that patient characteristics, not provider characteristics, drive ED management decisions for discharged hypertensive patients.

The current literature is consistent in advocating for follow-up care with a primary care provider.Reference Mancia, Fagard and Narkiewicz 7 , Reference Hackam, Quinn and Ravani 9 , Reference Decker, Godwin and Hess 10 Currently, however, there are few data to guide the number of days within which such patients should be seen; ACEP has identified this as an area in need of future study.Reference Wolf, Lo and Shih 8 In our study, recommendations for timing of follow-up care varied by patient presentation, but the large majority of participants endorsed follow-up within seven days.

LIMITATIONS

The survey was conducted within the GTA using a convenience sample; as such, the results may not be generalizable. Lack of funding prevented extension of the in-person survey to more than seven sites, resulting in a relatively small sample size. We avoided electronic surveys because of their generally poor participation rates.Reference Hollowell, Patel and Bales 12 , Reference VanDenKerkhof, Parlow and Goldstein 13 Since physicians who attend rounds may represent the most academically motivated physicians, our results may not represent a more general emergency physician population. However, it was our goal to capture the practice patterns of such individuals for use as a potential practice “yardstick.” The proportion of participants who reported that they had a threshold BP for prescribing antihypertensive medication was lower than the number who would prescribe using the specific clinical scenario; this could be because some physicians did not feel they had a threshold, but when faced with a specific patient, actually did. Anecdotally, many staff indicated that they wished they could have responded “it depends” to some of the questions. We kept the survey short in order to encourage a high response rate, but recognize and acknowledge that this limited the number of response variations we were able to capture.

CONCLUSIONS

Half of surveyed emergency physicians report having a BP threshold to start an antihypertensive; BP levels and number of patient comorbidities were associated with a modification of the decision, while physician characteristics were not. Most surveyed physicians recommended follow-up care within seven days of ED discharge.

Acknowledgments

This study was an unfunded project. Dr. Atzema is supported by a New Investigator Award from the HSFO, the Practice Plan of the Department of Emergency Services at Sunnybrook Health Sciences, the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, and the Sunnybrook Research Institute. The Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario had no involvement in the design or conduct of the study, data management or analysis, or manuscript preparation, review, or authorization for submission. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Competing Interests: Dr. Atzema is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation. The authors report no other competing interests.