CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Heavy users of cannabis increasingly present to the emergency department (ED) with unremitting vomiting, yet the precise cause of hyperemesis cannabis remains unknown.

What did this study ask?

Using hair to quantify longer-term exposure, do hyperemesis cannabis cases differ from other users with regards to their phytocannabinoid exposure profile?

What did this study find?

Cases and controls including ED patients with visits unrelated to cannabis had comparably high Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (and low cannabidiol) hair concentrations.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

In counselling patients with hyperemesis cannabis, clinicians should highlight the uncertainties of surrounding exposure and recommend drug-free intervals or abstinence.

INTRODUCTION

Little is known about cannabis (or “cannabinoid”) hyperemesis syndrome, a newly recognized condition in which frequent cannabis users experience bouts of protracted vomiting.Reference Sorensen, DeSanto, Borgelt, Phillips and Monte1–Reference Richards, Gordon, Danielson and Moulin4 Now a leading cause of vomiting in emergency patients,Reference Sorensen, DeSanto, Borgelt, Phillips and Monte1–Reference Habboushe, Rubin, Liu and Hoffman3, Reference Hernandez, Paty and Price5 its cause remains unknown. Is it merely the predictable result of accumulated exposure to increasingly potent cannabis, or poor quality/contaminated plant product, or an idiosyncratic reaction in a vulnerable subset like other episodic vomiting conditions (e.g., hyperemesis gravidarum)?Reference Sorensen, DeSanto, Borgelt, Phillips and Monte1, Reference Richards, Gordon, Danielson and Moulin4, Reference Richards6

To quantify the average exposure to cannabis over many weeks, we collected hair from patients being interviewed as part of a larger case-control study.Reference Albert7 We wondered whether emergency department (ED) patients with cannabis hyperemesis syndrome (cases) had higher concentrations of the four principal phytocannabinoids detectable in hair, as compared with recreational users without hyperemesis (controls).

METHODS

We approached consecutive eligible adult cases within two weeks of their index emergency visit. The case inclusion criteria were: chief complaint of vomiting, working diagnosis of cannabis hyperemesis syndrome, ≥2 episodes of severe vomiting in the prior year, and ≥3 days/week of cannabis use for ≥6 months. We excluded current synthetic cannabinoid or chronic opioid users and acute overdoses of drugs including ethanol. Cases were matched by age and sex to: 1) recreational user (RU) controls who were recreational cannabis users without hyperemesis; and 2) ED controls who comprised the general emergency patient population, irrespective of cannabis use. Subjects provided written informed consent, and the institutional research ethics board approved this research.

We targeted a one-month interval from the index visit to the standardized interview, given the lag before new hair appears above the scalp.Reference Pragst and Balikova8 During the interview, we obtained urine and two samples of approximately 75 strands of hair cut from the scalp vertex. Hair samples were batch analyzed at an independent laboratory blinded to subject information (Appendix A). For the primary analysis, we retained only subjects who reported ongoing, recent use and whose urine immunoassay (Triage™ TOX 11; Alere, Waltham MA) was positive for Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; threshold 50 ng/mL).

RESULTS

The parent study met its target enrolment of 20 cases; four were interviewed more than a month after their last cannabis use and had negative urine THC. Sixteen of the 22 (73%) RU controls and 14 of the 39 (36%) ED controls had positive urine THC corroborating recent cannabis use and, thus, met the criteria for the analytical study. Hair and urine were harvested 29 days (median; interquartile range [IQR] 19, 65) after the index visit (Supplementary Figure 1).

Cases were mostly men in the third or fourth decade of life who reported daily use of cannabis, averaging 7 (IQR 3.5, 11) g/week (Supplementary Table 1). The RU and ED controls with positive urine THC reported similarly frequent and heavy use, at 5 (IQR 1.5, 8.3) g/week and 5.8 (IQR 2.6, 8.1) g/week, respectively. Testing the hair for cannabinoids, opiates, cocaine, or amphetamines was highly concordant with the urine, and hair cannabinoid concentrations correlated moderately with the subjects’ self-reported weekly cannabis consumption (Figure Supplementary 2).

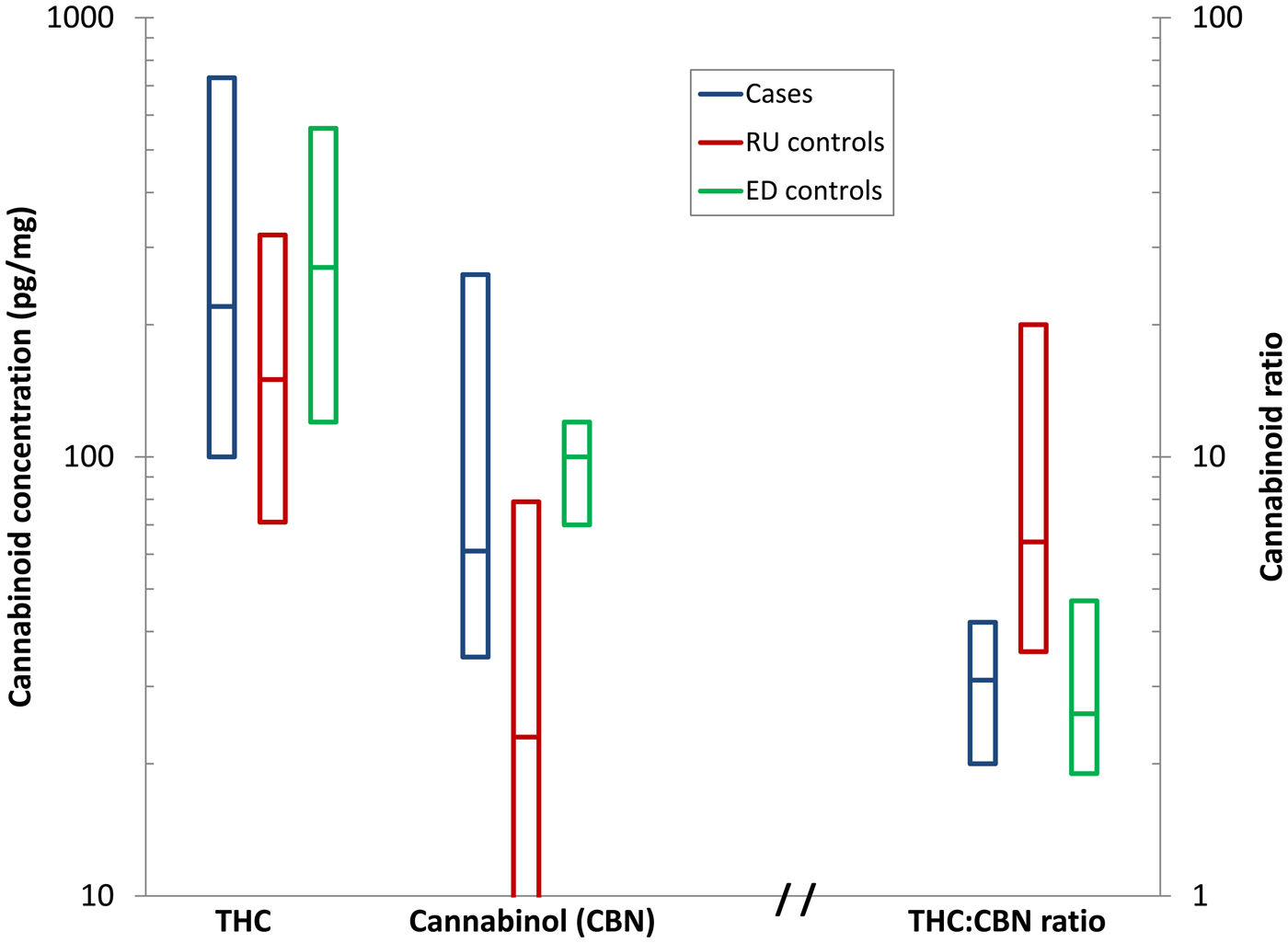

In the primary analysis, THC and cannabinol (CBN) concentrations demonstrated considerable overlap between cases and controls (Figure 1), but cannabidiol (CBD) and 11-nor-9-carboxy-THC (THC-COOH) were often below the limit of quantification (Supplementary Table 2). Adjusted for age and sex, there were only small and statistically insignificant differences between the groups with regards to hair cannabinoid concentrations (Supplementary Table 3). The THC:CBN ratio was 2.6 fold (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.3–5.7) lower in the cases than the RU controls, mostly because of higher CBN concentrations in the cases yet was similar in the cases vs. the ED controls.

Figure 1. Median and IQR hair Δ9-THC and cannabinol (CBN) concentrations and their ratio between cases with hyperemesis cannabis, recreational users without vomiting (RU controls), and ED patients seen for unrelated conditions (ED controls), each of whom had positive urine immunoassay and admitted to recent cannabis use.

To corroborate self-reported abstinence and to assess the potential for surface deposition from recent smoking and/or drug handling, we examined the persistence over time of hair THC and CBN concentrations among all enrolled patients, including those with negative urine THC. Hair cannabinoid concentrations decreased but remained quantifiable among patients who had used during the previous month but became mostly undetectable when abstinent for two months or longer (Figure Supplementary 3).

DISCUSSION

One might assume that the remarkable increase in ED patients with hyperemesis cannabis is because of both the increasing potency of cannabis and its increasingly heavy use following broad societal normalization. If so, one would expect much higher concentrations of phytocannabinoids in the hair of patients with cannabis hyperemesis syndrome. Our findings run counter to this assumption. Instead, the wide overlap in hair concentrations between cases and controls suggests a more idiosyncratic mechanism, perhaps akin to hyperemesis gravidarum, a different pathophysiologic cause than the principal cannabinoids, or an episodic trigger that remains to be identified. Accordingly, the popular term, “cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome,” seems inappropriately specific to us and others.Reference Dezieck, Hafez and Conicella9

These hair findings also demonstrate that heavy cannabis use is necessary, but not sufficient, for developing hyperemesis. Hair concentrations of THC and CBN were comparable to those of other studies involving heavy daily users.Reference Skopp, Strohbeck-Kuehner, Mann and Hermann10–Reference Taylor, Lees and Henderson12 These findings are particularly relevant for the emergency physician when counselling these patients who seek credible information at a teachable moment. While awareness of this syndrome is slowly increasing among recreational users, patients may be reluctant to accept recommendations for abstinence, given their seemingly unaffected peers. Physicians, in turn, are limited by the largely anecdotal evidence base to the disorder.

Our findings are also remarkable for two other observations: the comparably high hair cannabinoid concentrations in one-third of young patients being seen in the ED for unrelated reasons and the extremely low CBD concentrations relative to THC and CBN, as compared with older studies.Reference Skopp, Strohbeck-Kuehner, Mann and Hermann10 The first observation demonstrates that many young men and women being seen in our ED are heavy, daily users of cannabis. The second confirms both a marked increase in THC and decrease in CBD in recreational cannabis over the last two decades. Both changes are equally concerning, as CBD is believed to modulate the other adverse effects of THC.Reference Potter, Hammond, Tuffnell, Walker and Di Forti13–Reference Freeman, van der Pol and Kuijpers16

We doubt that an unrelated noxious contaminant or adulterant is responsible as in the apocryphal “bad batch theory.” The well-known acute effects of cannabis on appetite and nausea implicate the phytocannabinoids themselves by lex parsimoniae. Cannabinoids are highly lipophilic and accumulate in peripheral fat stores with heavy use. We speculate that some emetogenic cannabinoids are released as these stores are mobilized during fasting, resulting in anorexia, vomiting, and further ketosis, releasing yet more cannabinoids from the peripheral stores. The brief respite reportedly afforded by a hot shower may be the result of reduced thermogenesis and adipose tissue catabolism, slowing this cycle. For this reason, we recommend that patients with ketosis and hyperemesis receive dextrose-containing fluids and warm blankets, in addition to crystalloids.

There were limitations related to any hair analysis. Drugs can be incorporated into hair through multiple routes including sweat, sebum, and smoke deposition.Reference Cooper, Kronstrand and Kintz17, Reference Moosmann, Roth and Auwärter18 While the segment analyzed reflects approximately two months of hair growth and a lag of approximately one month from hair formation, surface deposition despite in vivo and ex vivo washing shortens these time windows. If patients with hyperemesis were prone to high peaks then troughs from binges, followed by abstinence, their average would resemble the controls with more moderate but sustained use. CBD and THC-COOH are often below the limit of quantification, even in heavy users,Reference Huestis, Gustafson and Moolchan11, Reference Taylor, Lees and Henderson12 precluding our ability to compare these cannabinoids or their exact ratios between the groups.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, patients with cannabis hyperemesis syndrome who were seen in the ED have comparable hair cannabinoid concentrations relative to their peers without hyperemesis. These non-intuitive findings underline our limited understanding of the effects of chronic heavy cannabis use, including the role of specific phytocannabinoids in cannabis hyperemesis syndrome. This uncertainty, combined with the high prevalence of heavy use in the general ED population, lends strong support to public health initiatives intended to discourage excessive use and to countervail renewed enthusiasm for the benefits of cannabis.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2018.479.

Acknowledgements

Presented at the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians Annual Meeting, Whistler BC, June 2017. KA and MLAS conceived the study and designed it with AD and LCH. KA recruited subjects, conducted the interviews, obtained the hair and urine samples under the supervision of MLAS, and managed the data. JG provided technical expertise regarding the hair analyses and their interpretation. AD provided statistical advice and analyzed the data. MLAS drafted and took responsibility for the manuscript as a whole, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.