INTRODUCTION

In-hospital cardiac arrest is a common event, and overall survival to hospital discharge rarely exceeds 22%.Reference Mozaffarian, Benjamin and Go 1 , Reference Peberdy, Kaye and Ornato 2 A number of in-hospital cardiac arrest patients (18%) have an abnormal electrical heart rhythm that could be fixed with an electrical shock or defibrillation.Reference Chan, Krumholz and Spertus 3 Cardiac arrest victims are most likely to survive when they are defibrillated within 3 to 5 minutes.Reference Kleinman, Brennan and Goldberger 4 Defibrillation is usually provided by a resuscitation team responsible for providing such care in the whole hospital.Reference Sandroni, Ferro and Santangelo 5 Unfortunately, our own data suggest this team cannot always arrive at the patient’s bedside quickly, leading to an average delay of 9 minutes before defibrillation occurs.Reference Chehadi, Vaillancourt and Gatta 6 Nurses and respiratory therapists are often the first ones at the patient’s bedside. They are trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and can use automated external defibrillators (AED) during out-of-hospital cardiac arrests,Reference Murphy and Fitzsimons 7 - Reference Makinen, Aune and Niemi-Murola 10 but are most commonly not allowed to use an AED during in-hospital cardiac arrests. This is true for nurses because AED use is considered a regulated health professional act in most jurisdictions, 11 , 12 and for respiratory therapists as a common institutional policy. There are limited reports on the attempted use of AEDs by nurses during in-hospital cardiac arrests.Reference Destro, Marzaloni and Sermasi 13 - Reference Hanefeld, Lichte and Mentges-Schroter 15 We need to better understand what would motivate nurses and respiratory therapists to use AEDs if we are to successfully implement such a program.Reference De Regge, Monsieurs and Vandewoude 16 , Reference Kenward, Castle and Hodgetts 17

Theoretical framework

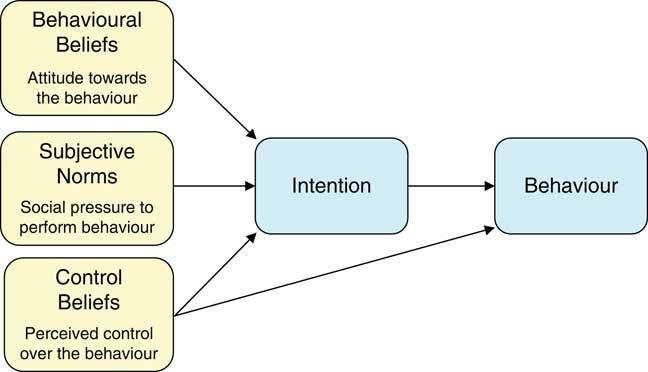

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is a conceptual framework very commonly used in health care studies exploring the factors that influence and predict an individual’s intention to engage in a behaviour (e.g., using an AED).Reference Ajzen 18 The likelihood of engaging in a behaviour is determined by the strength of the individual’s intentions to carry out the behaviour and their perceived behavioural control over carrying out the action.Reference Ajzen 18 - Reference Bunce and Birdi 21 Intention is determined by measuring the following three predictive variables: attitudes/behavioural beliefs (whether the individual is in favour of doing something), subjective normative beliefs (social pressures), and control beliefs (whether the individual feels in control of engaging in a behaviour). Measuring an individual’s intention to engage in a particular behaviour has been shown to correlate well with actually performing the behaviour.Reference Ajzen 18 Those theoretically derived determinants of behaviour can later be mapped to specific behavioural change techniques.Reference Michie, Johnston and Francis 22 This framework was successful in nursing clinical trials on promoting healthy living,Reference Kelley and Abraham 23 administering opioids for pain relief,Reference Edwards, Nash and Najman 24 and performing venipunctures according to universal precautions.Reference Godin 25

The purpose of this qualitative study is to identify determinants of behaviour perceived to influence the intention of nurses and respiratory therapists to use an AED during in-hospital cardiac arrest before the arrival of the resuscitation team.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews based on the constructs of TPB (Figure 1),Reference Ajzen 18 - Reference Bunce and Birdi 21 and developed our interview guide as described by Francis et al.Reference Francis, Eccles and Johnston 26

Figure 1 The theory of planned behaviour.

Setting

This study was conducted at the Ottawa Hospital – Civic, General, and Riverside campuses. The Civic and General campuses respectively have 456 and 533 inpatient beds, as well as outpatient clinics and day units. The Riverside campus has no inpatient beds, is composed solely of outpatient clinics and day units, and does not have access to a resuscitation team. There is a medical directive in place at the Ottawa Hospital allowing critical care and emergency nurses to use manual defibrillators, and nurses working in locations not accessible to the resuscitation team to use AEDs.

Study population

We used a purposeful sampling strategy to ensure participation of nurses and respiratory therapists from various departments, with varying levels of experience, and different medical directives in place regarding defibrillation. We approached clinical managers from hospital units of interest to help identify individuals who were interested in participating in the interviews. We recruited nurses from the following units: medicine, surgery, geriatrics, neurology, emergency medicine, intensive care, rehabilitation centre, and outpatient clinics. We recruited respiratory therapists from the following units: operating room, emergency medicine, intensive care, neonatology, and those rotating through various medical/surgical wards. Our institution requires that all nurses and respiratory therapists update their CPR + defibrillation certification yearly. We conducted this study after receiving research ethics approval from the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board. Nurses and respiratory therapists voluntarily participated in this study and gave written informed consent. Interviews were conducted outside of working hours, and participants were compensated $50 CDN for their time.

Methods of measurement

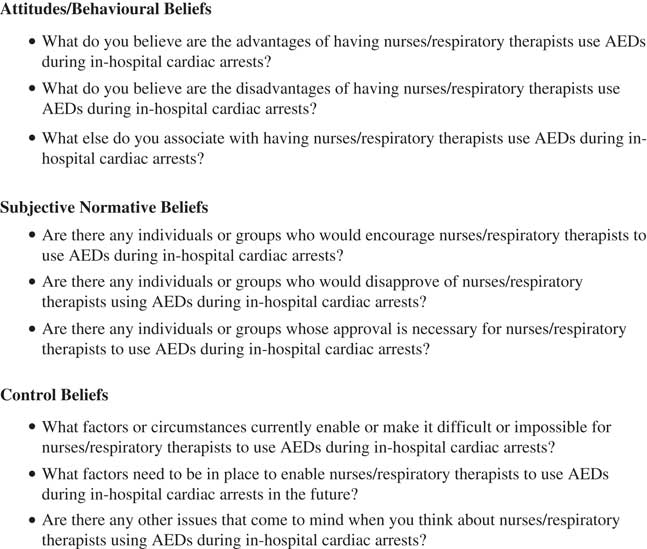

All interviews were conducted in person (except for one interview conducted by telephone). They were conducted by a single interviewer (JA) using a semi-structured open-ended interview guide based on the TPB standard practices.Reference Francis, Eccles and Johnston 26 Examples of questions asked for each TPB construct are presented in Figure 2. With the participant’s consent, interviews were recorded and then transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were verified by the interviewer prior to analysis. We recruited and interviewed new participants until data saturation was achieved (meaning until we obtained no new information during the interview process).Reference Francis, Johnston and Robertson 27

Figure 2 Examples of interview questions.

Main data analysis

Two independent researchers (JA and JLJ) performed inductive analyses of the transcripts to identify common themes or codes. The codes were categorized according to the constructs of the TPB and were counted. A given code could be mentioned several times in an interview but would be counted once only. Additionally, a code was counted as present in an interview if either investigator identified it in the transcript. As soon as all of the transcripts were coded, the codes were examined for common meanings and combined by way of consensus. We listed the codes for each TPB construct in order of frequency and, as suggested by Francis et al.,Reference Francis, Eccles and Johnston 26 retained those representing more than 75% of all codes counted. For example, if a common code appeared 50 times, a second code 20 times, a third code 5 times, and 25 other codes each appeared once only, we would have retained the three first codes representing 75% of all codes counted. In addition to these descriptive statistics, we present a narrative interpretation of the data with verbatim illustrative quotes from the participants.

RESULTS

We completed 24 interviews between June and July 2009. The mean age of the participants was 41 years; most of them were female, registered nurses, and full-time employees with 16 years of experience on average (Table 1). All participants stated that they had been involved in cardiac arrest resuscitation; while most provided CPR to a patient in cardiac arrest, only a few were allowed to use a defibrillator.

Table 1 Characteristics of the 24 interview participants

AED=automated external defibrillation; CCU=coronary care unit; CPR=cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ICU=intensive care unit; RN=registered nurse; RPN=registered practical nurse;

RT=respiratory therapist; SD=standard deviation.

We reached data saturation by the 24th interview, with minimal new information gathered in the last 4 interviews. This resulted in a total of 20 behavioural beliefs, 17 subjective norms, and 22 control beliefs (Tables 2-4). The codes were listed in order of frequency within each TPB construct, and only the codes representing more than 75% of all codes identified per construct were retained.Reference Francis, Eccles and Johnston 26 After this exercise, eight behavioural beliefs, nine subjective norms, and eight control beliefs remained. Tables 2, 3, and 4 contain a number of verbatim quotes from study participants. We present narrative descriptions of the codes/beliefs in the following paragraphs.

Table 2 Behavioural beliefs

* >75% of all codes reached.

Table 3 Subjective norms

* >75% of all codes reached.

Table 4 Control beliefs

* >75% of all codes reached.

Behavioural beliefs

-

1. Using an AED may affect time to defibrillation.

Almost all participants acknowledged that time is important when it comes to defibrillation, and 16 participants thought that having nurses and respiratory therapists use AEDs would decrease the time to first shock. In contrast, five participants were unsure as to whether being able to use the AED would decrease the time to first shock because they felt the resuscitation team arrives very quickly. One individual believed that being able to use the AED would not decrease the time to first shock because the patient arrives with the resuscitation team.

-

2. Using an AED may affect patient survival.

Most participants believed that a patient would be more likely to survive if he or she could use an AED, and that survival was often associated with a shorter time to shock delivery. One respiratory therapist felt that patient survival could decrease if an AED were used because it would require changing their focus away from airway management.

-

3. An AED is a simple machine and is used in the community.

A large proportion of participants felt that AEDs are simple machines to use and that a variety of non-medical professionals are currently using them safely.

-

4. An AED can/cannot accurately recognize heart rhythm.

Participants had diverging opinions about whether AEDs accurately recognize cardiac rhythms. Ten individuals were confident that AEDs could correctly identify cardiac rhythm, whereas six others had doubts. In addition, four individuals mentioned wanting to be able to see the rhythm themselves (which is not shown by AEDs) to determine whether a shock was necessary.

-

5. Using an AED may cause more/less harm to the patient, myself, or others.

Participants also expressed diverging opinions regarding harm to the patient, themselves, or others when using the AED. Six individuals felt that using an AED could result in less harm done to patients by possibly avoiding the need for CPR and resulting broken ribs. Many understood that using an AED would not harm the patient, themselves, or their coworkers because they are aware of the proper procedure when defibrillating; 13 participants were unsure or concerned that the patient could be harmed by inappropriately receiving a shock, or that they or their coworkers could be harmed by receiving a shock.

-

6. Using an AED may affect the stress experienced during a resuscitation.

More than half of the participants expressed opinions regarding the stress that would be involved when using the AED. Three participants felt that using the AED could either increase or decrease the stress that they felt, depending on the situation, two participants felt that they would experience less stress, and nine participants felt that they would experience more stress during the cardiac arrest if they had to use an AED.

-

7. First responder defibrillation is important.

More than half of the participants believed that the first responder to a cardiac arrest event should be allowed to use the AED. They expressed that first responder defibrillation is an important part of the initial resuscitation attempt prior to resuscitation team arrival.

-

8. Using the AED is the best thing for the patient.

Eleven participants expressed that using an AED is the best treatment for the patient. Participants acknowledged the role of CPR and medications in the resuscitation effort but felt that using an AED would be the best management option.

Subjective norms

According to interviewees, subjective norms had little influence on the decision to use an AED compared to behavioural and control beliefs.

-

1. Individual group peer-pressure

Of the nine subjective norms most commonly identified by the participants, eight represented individuals or groups that would have some influence on the participant’s intention to use the AED. They are in order of decreasing frequency: physicians, hospital administration, other health care professionals, colleagues, College of Nurses of Ontario/College of Respiratory Therapists of Ontario, patients, the public, and managers. For example, the approval/expectation of physicians responding to a cardiac arrest was perceived to be of some importance.

-

2. Collective peer-pressure

One subjective norm, identified by 11 of the participants, was not a specific individual or group but rather was described as the culture or common acceptance within the hospital supporting AED use.

Control beliefs

-

1. Training on AED

All interviewees expressed the opinion that having the appropriate training is a facilitator to using AEDs. Only three individuals felt that their current training was sufficient for them to use an AED; among these three, two were allowed to use an AED in the hospital setting. Nine individuals mentioned having received training to use an AED but felt they would benefit from additional or more frequent training.

-

2. Policy allowing AED use

The vast majority of participants stated that a hospital policy outlining the use of AEDs by nurses and respiratory therapists would facilitate their using an AED. Eight individuals felt that it would be necessary to have the support and/or approval of their regulatory college before they could use an AED during in-hospital cardiac arrests. Some participants were concerned that legal actions could result from their use of an AED, unless a hospital policy was in place.

-

3. Familiarity with AED

Most participants expressed the importance of being familiar with the AED prior to using it. Familiarity with the AED could be achieved by being responsible for its regular maintenance and scheduled verification of proper function.

-

4. Role in cardiac arrest resuscitation

Numerous participants mentioned that defibrillation is the role of physicians, the resuscitation team, or advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) certified health care providers. Participants were concerned that using an AED to defibrillate a patient would mean making decisions that physicians normally make. Of note, 16 of 17 individuals who were not allowed to use an AED/defibrillator expressed this opinion, whereas only 3 of 7 individuals currently allowed to use an AED/defibrillator shared this opinion.

-

5. Machine availability and proximity

A large proportion of participants stated that, for AEDs to be useful, they should be distributed throughout the hospital in such a way to assure their proximity and rapid access.

-

6. Experience with cardiac arrest resuscitation

Over two thirds of participants stressed the importance of having experience dealing with cardiac arrest situations as a facilitator to using an AED. It was perceived that lack of exposure to cardiac arrest situations would hinder AED use.

-

7. Other tasks to do during resuscitation

More than half of the participants were concerned with having other tasks that they were responsible for during cardiac arrest resuscitation, and that using an AED represented another task added on to an already overtaxed health care provider. Notably, all of the respiratory therapists we interviewed mentioned being already too preoccupied with managing the patient’s airway.

-

8. Trust the AED to work or not

Half of the participants expressed an opinion regarding the proper functioning of an AED. Five mentioned that they would trust the AED to work properly; four were not convinced that they reliably would, and three participants were concerned about malfunction.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study used the constructs of the TPB to identify the factors influencing the intention of nurses and respiratory therapists to use an AED during in-hospital cardiac arrests. Overall, participants expressed a positive attitude toward AED use. The most common behavioural beliefs identified include timeliness of defibrillation, patient survival, simplicity of AED use, accuracy of rhythm recognition, and harm to the patient, self, or others. Although several subjective norms were acknowledged, including physicians and the hospital administration, these themes were mentioned less frequently than the behavioural beliefs and control beliefs. The most common control beliefs identified consisted of lack of training on AED use, policy allowing AED use, familiarity with the AED, AED availability, and roles during resuscitation.

It is important to mention that, in most institutions, critical care nurses and nurses working in the emergency department can already provide defibrillation during in-hospital cardiac arrests. This is most often resulting from the adoption of a medical directive allowing the use of manual defibrillators rather than AEDs. Our participants included such critical care and emergency nurses. They also shared their respective barriers to AED use and defibrillation.

The themes identified in this qualitative study represent areas to target in order to facilitate policy change and behaviour change regarding AED use during cardiac arrest in both critical care and non-critical care areas of the hospital. Those theoretically derived determinants of participants’ intention to use an AED can be mapped to behavioural change techniques to be implemented in a multi-interventional study design.Reference Michie, Johnston and Francis 22 Such an intervention could help clarify how the intention to use an AED (as measured by the TPB constructs) is linked to the behaviour of actually using one in a cardiac arrest situation, and how nurses and respiratory therapists may differ in their use of AEDs.

Dwyer also published a qualitative study examining the defibrillation-related beliefs of nurses in rural Australia using focus groups and the TPB.Reference Dwyer, Mosel Williams and Mummery 28 Among the 12 recruited participants, 7 were allowed to defibrillate patients, most often using manual defibrillators. Our study found very similar results in discussions with urban nurses and respiratory therapists. Of note, a theme common to both Dwyer’s and the current study is the participants’ concern regarding the safety and accuracy of AEDs, with their ability to recognize electrical rhythms accurately, and with the perceived potential harm to the user and patients.Reference Dwyer, Mosel Williams and Mummery 28 A number of studies has shown that AEDs can safely be used by both trained health care providers and lay responders,Reference Peberdy, Kaye and Ornato 2 , Reference Hanefeld, Lichte and Mentges-Schroter 15 , Reference Caffrey, Willoughby and Pepe 29 - Reference White, Hankins and Bugliosi 32 and that they can accurately identify cardiac rhythms.Reference Dickey and Adgey 33 - Reference Kerber, Becker and Bourland 35

It is also important to consider the potential impact of such an AED program. Chan conducted a multi-centre cohort study of 11,695 cardiac arrests examining the effect of AED use in-hospital.Reference Chan, Krumholz and Spertus 3 This study reports overall lower survival to hospital discharge with AED use (16.3% v. 19.3%; p<0.001).Reference Chan, Krumholz and Spertus 3 Chan’s study did not find a decreased time to defibrillation with AED use, which may contribute to the overall lower survival. Furthermore, the database/registry used for that study did not specify who was using the AED – nurses and other allied health professionals, or physicians. An AED may delay defibrillation in the hands of a physician due to the time needed for automated rhythm analysis compared to manual rhythm recognition and defibrillation.

LIMITATIONS

The TPB is only one of many existing frameworks to study and analyse behaviour. Although it focuses on the “intension” to adopt a behaviour, the TPB is a rigorous framework very commonly used in health care studies. Qualitative inductive analysis may possibly be influenced by the bias of the investigators performing the analysis. We attempted to limit this bias by having two independent investigators (neither of which were a nurse or a respiratory therapist) complete the analysis and resolve conflicts by way of consensus.

CONCLUSIONS

Most nurses and respiratory therapists would agree to use an AED during in-hospital cardiac arrests if permitted to do so by a medical directive. Successful implementation would require educational initiatives focusing on safety and efficacy of AEDs, support from physicians and hospital administrators, and additional training on AED use. These beliefs are important to address through future research using appropriately selected behavioural change techniques and policy changes.

Acknowledgements

This article’s abstract was presented at the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians conference in Montréal, QC, Canada, 2010. We would like to acknowledge the help and support of Dr. Ginette Rogers, RN, PhD (Senior Vice-President, Professional Practice and Chief Nursing Executive), Mrs. Evelyn Kerr, RN/IA, MScN (Director of Nursing Clinical Practice), Mrs. Renee Pageau (Corporate RT Clinical Practice Coordinator), the clinical unit managers from which our participants were recruited, and, not the least of which, all of the participants who share their off-duty time with us for the purpose of this important project. We would also like to acknowledge the administrative support of Mrs. Angela Marcantonio for her role in processing and submitting this study material.

Competing interests: This study was supported by the Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Ottawa, and the Summer Studentship Program, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa.