INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by chronic, persistent, not fully reversible airway obstruction, systemic manifestations, and increasing frequency and severity of exacerbations that frequently result in visits to the emergency department (ED). 1 The burden of COPD-related care in the ED is significant.Reference Yeatts, Lippmann and Waller 2 , Reference FitzGerald, Haddon and Bradly-Kennedy 3 Approximately 17% of COPD patients in North America and Europe report having at least one ED visit per year due to symptom exacerbations.Reference Chapman, Bourbeau and Rance 4 About 1.4% of all ED visits in Canada are attributed to COPD.Reference Rowe, Cydulka and Tsai 5 The rates of COPD-related ED visits in Alberta in individuals older than 55 years of age ranged from 25.6 per 1,000 population in 1999 to 25.1 per 1,000 population in 2005, with an average of 2.2 visits per patient per year.Reference Rosychuk, Voaklander and Senthilselvan 6 The proportion of ED visits resulting in admission is often high, since the airway obstruction associated with exacerbations is slow to resolve.Reference Rosychuk, Voaklander and Senthilselvan 6

Aboriginal peoples in Canada (First Nations, Métis and Inuit) have a higher prevalence and incidence of COPD compared to non-Aboriginals.Reference Ospina, Voaklander and Senthilselvan 7 , Reference Martens, Bartlett and Burland 8 There remain important gaps in our knowledge about the burden of COPD in Aboriginal people relative to their non-Aboriginal counterparts,Reference Ospina, Voaklander and Stickland 9 and there is limited evidence about the patterns of ED use following a diagnosis of COPD in these populations. Analyses of administrative health data in Alberta have found that First Nations people are twice as likely to have an ED visit for COPD than non-Aboriginals.Reference Rosychuk, Voaklander and Senthilselvan 6 , Reference Sin, Wells and Svenson 10 These studies, however, combined both asthma and COPD-related visits, spanned relatively short periods of follow-up, or failed to include other Aboriginal groups in the analyses.

The purpose of our study was to compare the rates of ED visits after a diagnosis of COPD in all three Aboriginal groups (Registered First Nations, Métis and Inuit) and a non-Aboriginal cohort with COPD, and to explore characteristics of these ED visits.

METHODS

Study design and data sources

This was a retrospective cohort study based on linkage of administrative health data in Alberta (Canada). Alberta has just over four million residents, of which 6.2% report Aboriginal ancestry (52% First Nations people, 45% Métis and less than 1% Inuit). 11 Universal health coverage under the Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan (AHCIP) is provided to virtually all Albertans for all medically necessary physician and hospital services in the province. The federal government pays health premiums of Registered First Nations and Inuit, whereas the Métis receive health coverage from the provincial government, similar to the non-Aboriginal population in Alberta.

We used de-identified, individual-level, longitudinal data from administrative databases in Alberta for fiscal years 2002 to 2009 (April 1st of a given year to March 31st of the subsequent year) that were linked across datasets based on an encrypted unique personal health number. The AHCIP registry contains demographic information; the Alberta Ambulatory Care Classification System (ACCS) collects information on all ED visits in Alberta using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, enhanced Canadian version (ICD-10-CA) 12 for diagnosis coding. Claims for services provided by fee-for-service physicians and physicians paid under alternate payment plans with diagnostic fee codes based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) 13 are recorded in the Alberta Physician Claims Assessment System. Alberta Vital Statistics contains verified certificate data of all deaths in the province. The Métis Nation of Alberta (MNA) registry contains citizenship information for members of the Métis Nation of Alberta who identify themselves as Métis.

Study population

The Aboriginal cohort consisted of Registered First Nations people, Inuit (both identified in the AHCIP based on an alternate premium arrangement), and Métis included in the MNA registry. Non-Aboriginals were classified as individuals in the AHCIP without an alternate premium arrangement field nor included in the MNA registry. First Nations people without registration status 14 and Métis not registered in the MNA were considered non-Aboriginals because there is no reliable method to identify them within the general population.Reference Anderson, Smylie and Anderson 15 Individuals included in the cohorts were required to have had constant registration in the AHCIP between fiscal years 2002 to 2009, and be at least 35 of age at the beginning of each year. All Métis and Inuit in the AHCIP/population registry who met the eligibility criteria were included in the Aboriginal cohort, while random samples of eligible Registered First Nations people and non-Aboriginals were selected from the AHCIP/population registry for a ratio of five Registered First Nations people and five non-Aboriginals per Métis person included.

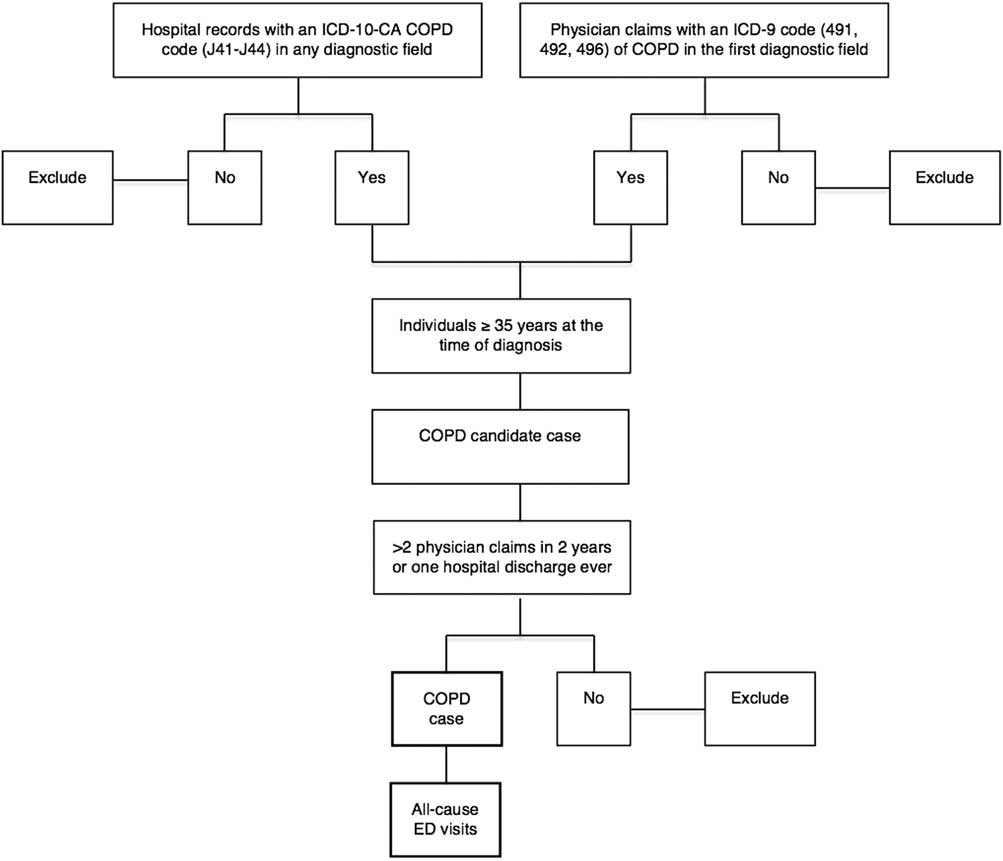

We identified individuals in the cohorts who were newly diagnosed with COPD during the study period according to the following validated case definition: individuals aged 35 years and older at the time of diagnosis who had at least two physician claims with an ICD-9 code of COPD (491, 492, 496) in the first diagnostic field in a two-year period, or one recording of an ICD-10-CA code (J41-J44) of COPD in any diagnostic field in the hospital file ever, whichever came first (Figure 1).Reference Gershon, Wang and Guan 16 , Reference Evans and McRae 17 This COPD algorithm has been previously validated with sensitivity of 68.4%, specificity of 93.5%, positive predictive value of 79.2%, and negative predictive value of 89.1%.Reference Gershon, Wang and Guan 16

Figure 1 Algorithm for COPD case identification in administrative databases.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the rate of all-cause ED visits. Only ED visits that occurred after the date of COPD diagnosis were included in the analysis. Secondary outcomes were ED length of stay (LOS) and disposition status at the end of ED visit.

The following sociodemographic information was extracted from the AHCIP registry: sex (male or female), age at the time of COPD diagnosis (35 to 64 years, 65 years and older), and area of residence (urban, rural, and remote) at COPD diagnosis. As there is no direct measure of socioeconomic status (SES) available from administrative health databases, the need for, and receipt of health care subsidies (full, partial, none) is considered a proxy measure of SES within the Canadian health care system.Reference Wang, Gabos and Mackenzie 18

Comorbidities were defined as the presence of one or more distinct common diseases in addition to COPD.Reference Sin, Anthonisen and Soriano 19 , Reference Chatila, Thomashow and Minai 20 We used validated case algorithms to identify the following comorbidities that have been associated with an increase in health services use in COPD patients: hypertension, 21 , Reference Tu, Campbell and Chen 22 diabetes mellitus, 23 ischemic heart disease,Reference Tu, Mitiku and Lee 24 asthma,Reference Huzel, Roos and Anthonisen 25 and osteoporosis.Reference Leslie, Lix and Yogendran 26

Annual rates of all-cause ED visits were calculated from fiscal years 2002 to 2009. The numerator was the number of episodes of ED care per person per year and the denominator was the person-time of observation, defined as the sum of the time that each person with COPD remained under observation from beginning of the fiscal year (if the person was diagnosed in previous years) or COPD diagnosis date (if the person was diagnosed during the year) until death, or end of fiscal year, whichever came first.

Incidence density rates of all-cause ED visits were calculated for the entire study period, with the numerator being the total number of episodes of ED care that occurred between 2002/2003 and 2009/2010 divided by total person-time of observation (the sum of the time that each person remained under observation from COPD diagnosis date until death, or end of study). All rates were expressed as number of events per 1,000 person-years with Poisson 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated around the estimates.Reference Rosner 27

Characteristics of ED visits were captured by median length of stay and proportions of disposition status at the end of the ED episode of care (discharged, admitted, death, left before completion of ED care). We calculated unadjusted rate ratios (RRs) with 95% CI for all-cause ED visits for the entire study period. Poisson regression models were used to adjust the RRs for other covariates at baseline with person-time considered as the offset in the modelReference Rosner 27 and the non-Aboriginal cohort as the reference category. Covariates fit in the Poisson model were sex, age group, SES proxy, area of residence and the presence of important comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, ischemic heart disease, asthma, diabetes mellitus and osteoporosis).

Two-sided p values less than 0.05 represented statistical significance for all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using Predictive Analysis Software Statistics for Mac® (PASW® version 18.0, IBM SPSS, Somers, NY).

The University of Alberta Health Research Ethics Board granted ethics approval to conduct this study. Individual patient consent was not required and patient records and information were anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 2,274 Aboriginal people (1,764 Registered First Nations, 329 Métis, and 181 Inuit) and 1,611 non-Aboriginals were newly diagnosed with COPD during the study period (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of study population

COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM=diabetes mellitus; IHD=ischemic heart disease.

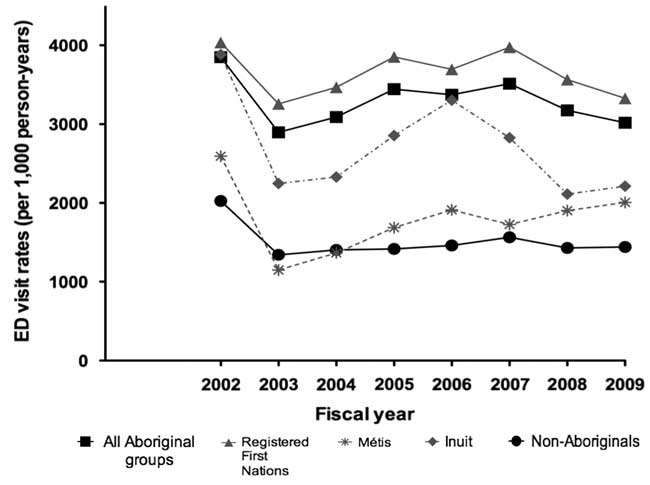

Overall, annual rates of all-cause ED visits in the Aboriginal groups diagnosed with COPD were consistently higher than those in their non-Aboriginal counterparts (Figure 2). For the entire study period, all-cause ED visit rates in all Aboriginal COPD groups combined (3,242.7 ED visits per 1,000 person-years; 95% CI: 3,205.4, 3,281.3) were higher than those of non-Aboriginals (1,460.1 ED visits per 1,000 person-years; 95% CI: 1,429.2, 1,492.3). Registered First Nations people with COPD had the highest rates of ED visits (3,612.5 ED visits per 1,000 person-years; 95% CI: 3,566.1, 3,659), followed by the Inuit (2,574.4 ED visits per 1,000 person-years; 95% CI: 2,460.1, 2,694.0) and the Métis (1,801.2 ED visits per 1,000 person-years; 95% CI: 1,730.1, 1,875.4).

Figure 2 Annual rates of all-cause ED visits in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal cohorts diagnosed with COPD, 2002 to 2009.

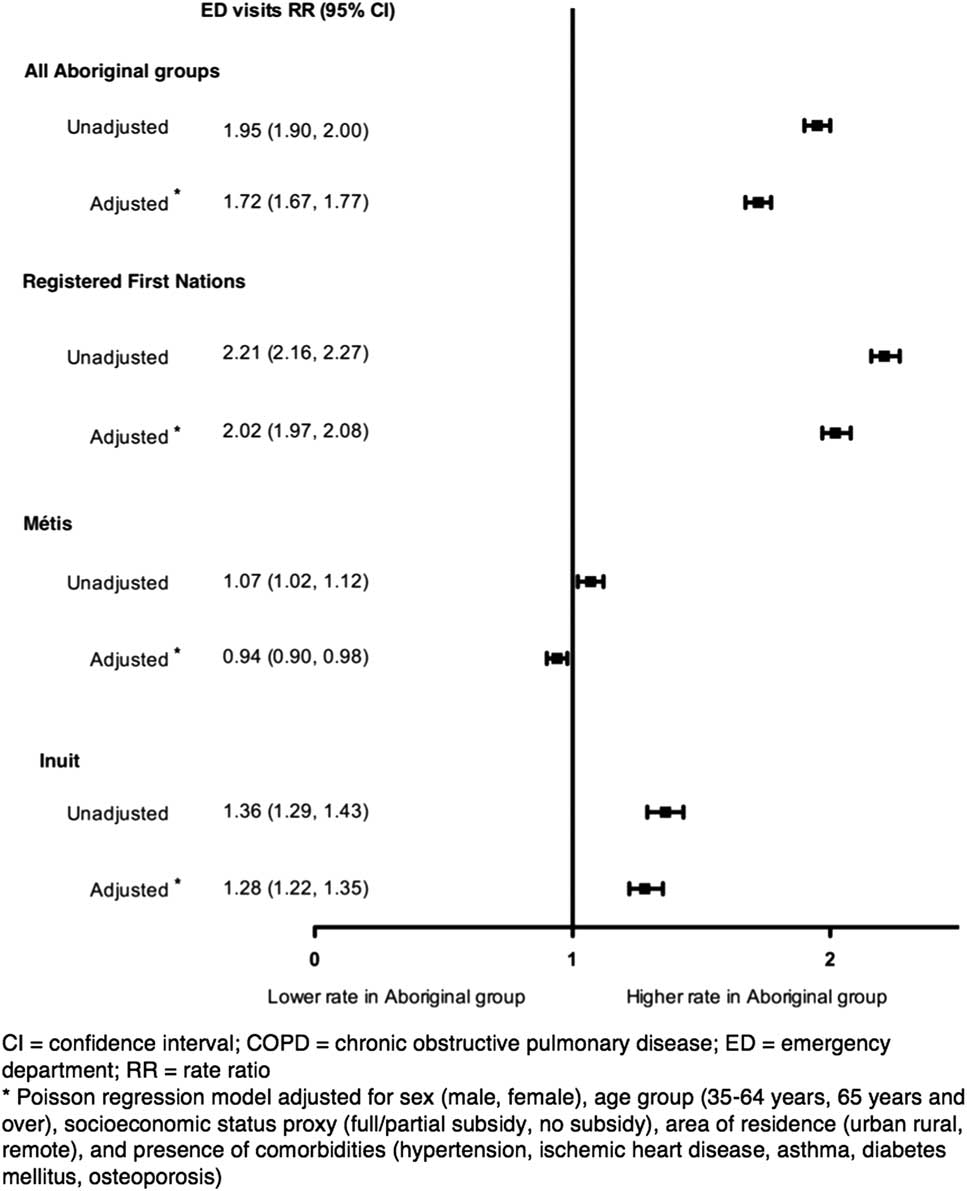

Figure 3 shows rate ratios of all-cause ED visits in Aboriginal people with COPD. After adjusting for important socioeconomic factors and the presence of comorbidities, we found that all-cause ED visit rates given COPD were significantly higher in the group of all Aboriginal peoples combined than those in the non-Aboriginal group (RRadj=1.72, 95% CI: 1.67, 1.77). Multivariate analyses for Aboriginal subtypes found that, compared to the non-Aboriginal group, all-cause ED visit rates in Registered First Nations people (RRadj=2.02; 95% CI: 1.97, 2.08) and the Inuit (RRadj=1.28; 95% CI: 1.22, 1.35) were significantly higher, but rates amongst the Métis were significantly lower (RRadj=0.94; 95% CI: 0.90, 0.98).

Figure 3 Rate ratios of all-cause ED visits in Aboriginal people with COPD.

The median ED LOS in Registered First Nations people (1 hour; IQR: 0, 4), Métis (1 hour; IQR: 0, 3) and Inuit (1 hour; IQR: 0, 3) were shorter than that of the non- Aboriginal group (2 hours; IQR: 1, 5). As shown in Table 2, compared to non-Aboriginals, there was a higher proportion of ED visits in Aboriginal people ending in discharge from the ED (77.7% versus 71.3%) or leaving before completion of care (5.0% versus 2.4%). In contrast, a higher proportion of non-Aboriginal individuals with COPD were admitted to hospital (17.2% versus 26%).

Table 2 Characteristics of emergency department visits of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal cohorts diagnosed with COPD from 2002 to 2009

CI=confidence interval; ED=emergency department; IQR=interquartile range; LOS=length of stay; left before completion of care included left without being seen and left against medical advice.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study in Canada to provide a comprehensive longitudinal assessment of the pattern of ED services following a diagnosis of COPD in the three Aboriginal groups of Canada compared to a non-Aboriginal reference group. Using a validated algorithm for case identification of COPD and after adjusting for important sociodemographic factors, we found that Aboriginal people with COPD as a whole had significantly higher rates of all-cause ED visits compared to non-Aboriginals with COPD. Aboriginal subgroups showed distinct patterns of ED visits following a diagnosis of COPD. Rates of all-cause ED visits were significantly higher in Registered First Nations people and Inuit, but lower in the Métis group compared to their non-Aboriginal counterparts. Despite having higher ED visit rates, Aboriginal people with COPD were found to spend approximately 1 hour less time in the ED than non-Aboriginals.

Our results are similar to those of studies comparing ED visit rates for COPD between Registered First Nations people and non-Aboriginal groups in Alberta: Registered First Nations people were more likely to visit the ED for COPD exacerbations.Reference Rosychuk, Voaklander and Senthilselvan 6 , Reference Sin, Wells and Svenson 10 The results, however, differ from those of Klein-Geltink and colleaguesReference Klein-Geltink, Khan and Cascagnette 28 who reported that the mean number of overall ED visits among those diagnosed with COPD were 1.3 times higher among Métis compared to the general population in Ontario, while there were no differences between the two groups in the proportion of COPD-specific ED visits.Reference Klein-Geltink, Khan and Cascagnette 28 Discrepancies in study results may be related to differences in the analytical approach and the observation period of the studies. There are no published data to compare the results of ED visits rates in Inuit with COPD.

Differences in ED visit rates in Aboriginal groups with COPD relative to their non-Aboriginal counterparts in our study may arise from a variety of factors that are determinants of quality of care in COPD. It is possible that Aboriginal people with COPD use more ED services, either because they have higher disease severityReference Pines, Asplin and Kaji 29 that leads to frequent or more severe exacerbations, or due to poorer chronic management for COPD and/or comorbidities that lead to treatment failure and disease relapse that requires frequent emergency care.Reference Restrepo, Alvarez and Wittnebel 30 It is also possible that certain Aboriginal groups use the ED as a “safety net of health care” rather than primary care providers, particularly if they belong to socially and economically disadvantaged communities.Reference Blanchard, Haywood and Scott 31 , Reference Browne, Smye and Rodney 32 Data from the 2006 Aboriginal Peoples Survey (APS) showed that the proportion of Aboriginal people who have a regular physician (81%) is lower than the national average in Canada (85%).Reference Tait 33 , Reference Janz, Seto and Turner 34 In particular, First Nations people living in rural and isolated communities are more likely to report difficulties accessing health providers, including regular physicians and specialists.Reference Wilson and Rosenberg 35 Similarly, the survey found that Métis and Inuit adults had poorer access to a regular physician compared to the general population.Reference Tait 33 , Reference Janz, Seto and Turner 34

Approximately 10% of individuals are diagnosed with COPD for the first time in the ED,Reference Aaron, Vandemheen and Hebert 36 suggesting that in many instances, the condition remains undetected at the primary care level and many individuals with COPD go to the ED rather than to physician offices for symptoms or conditions that could be otherwise managed out of the ED. The existence of barriers affecting the access to diagnosis and treatment for COPD, the shortage of regular family physicians, and in a broader perspective, an inadequate organization of the primary care services to address the needs of Aboriginal populations with COPD could account for the differences in the use of ED services between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal cohorts with COPD.

Other potentially explanatory factors underlying the observed patterns of ED attendance in Aboriginal people with COPD include cultural differences, perception of health services and providers, and health literacy issues. Evidence from qualitative research has established that, as a result of histories of abuse and discrimination and prior negative experiences with the health care system, Aboriginal people may not seek medical care at the frequency expected of Canadians in the general population.Reference Adelson 37 , Reference Richmond and Ross 38

We found that the three Aboriginal groups with COPD had shorter ED LOS than their non-Aboriginal counterparts, with differences in disposition status among groups. These findings could arise from either positive or negative factors: a shorter LOS may indicate that Aboriginal people are treated faster in the ED; alternatively, it may indicate that their condition could have been treated in outpatient settings and that the ED visit could have been avoided if better access to physician ambulatory services were available. Our analysis of ED disposition status revealed that more Aboriginal people with COPD left the ED before completion of care compared to their non-Aboriginal counterparts (5.0% versus 2.4%), and this could explain the shorter ED LOS. Post-hoc analyses showed that, compared to non-Aboriginal people with COPD, more Aboriginal people with COPD concluded their ED visits because they left against medical advice (LAMA) (3.9% versus 2.2%), or left without being seen (LWBS) (0.8% versus 0.2%). Further studies are required to explore the outcomes of ED visits and other characteristics of Aboriginal people and non-Aboriginals who are frequent users of ED services.

There are a number of limitations in this study inherent to the quality and comprehensiveness of administrative data. First, the process of diagnosing COPD is complex and imperfect. While the diagnosis of COPD was not clinically confirmed, the algorithm we used for case identification has been found to be both valid and accurate. To conduct a similar sized prospective clinical study would require an enormous funding commitment and many years of research compared to the efficiency of using administrative data.

Superficial clinical details in administrative databases precluded the acquisition of information on key sociodemographic and clinically important confounding variables to adjust the baseline risk for COPD in multivariate analyses. While the multivariate analyses adjusted for important covariates at baseline (e.g., sex, age, area of residence, SES, comorbidities), key factors such as disease severity, smoking history, and smoking status are not routinely captured in the administrative health datasets used for this study, and therefore could not be included in the analyses. Future studies using multi-level approaches would be needed to explore these differences further and to assess the impact of disease severity, smoking, ED geographic location, ED case-mix, and social determinants as potential barriers to health services access.Reference Marrone 39

Efforts to mitigate the misclassification bias affecting exposure (i.e., being Aboriginal) may not have been completely successful in our study. Limitations encountered in similar studies regarding the proper identification of non-Registered Aboriginal peoples persisted, although to a lesser degree. For example, an individual who was classified in the non-Aboriginal group may have been in fact, a non-Registered First Nations person or a Métis without citizenship registration under the MNA. It is also possible that First Nations peoples with Registered status and Métis individuals registered with the MNA may be different (in demographic or clinical terms) than non-Registered First Nations peoples and non-registered Métis in the province. In 2011, First Nations peoples without registration status represented 25.1% of the total number of First Nations peoples in Canada. 11 Similarly, it is estimated that as few as 30% of Métis in the province are members of the MNA, and therefore a substantial number of non-MNA Métis were not included in our study or were misclassified in the non-Aboriginal group. Misclassification bias in the study may have led to undercounting of approximately one-third of Aboriginal people in the province. If anything, the magnitude of the differences in epidemiological indicators of COPD between Aboriginal peoples and the non-Aboriginal populations has likely been underestimated as a result of misclassification of non-Registered First Nations people and non-MNA Métis, for had we had the correct classification of all Aboriginal people, such differences would have been more precise.

As we used a cohort design with linkage across provincial administrative health databases involving a large number of people and continuity of data over a relatively long follow-up period, we feel is is likely that our results can be generalized to all Aboriginal people in Alberta and allow inferences that can be applied to Aboriginal populations in other Canadian provinces.

CONCLUSION

Aboriginal people with COPD, as a whole, use almost twice the amount of ED services compared to non-Aboriginal people with COPD. The patterns of ED visits with COPD, however, differ among the three Aboriginal groups, with First Registered Nations people consistently showing higher rates in all indicators evaluated. Further research should explore whether barriers to accessing family physicians and other primary care services contribute to these differences.

Competing Interests: Dr. Ospina received financial support through a PhD Studentship Award from the Canadian Thoracic Society and the Canadian Lung Association. Dr. Stickland is supported by a New Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Dr. Rowe is supported by CIHR as a Tier I Canada Research Chair in Evidence-based Emergency Medicine through the Government of Canada (Ottawa, ON). This study is based on data provided by Alberta Health. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein are those of the researchers and do not necessarily represents the views of the Government of Alberta or Alberta Health. The authors have no other competing interests to declare.