INTRODUCTION

Emergency medicine (EM) is committed to medical education.Reference Gordon 1 Previous work by the Academic Section of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) demonstrates that our discipline is involved in teaching at every Canadian medical school.Reference Stiell, Artz and Lang 2 However, the volume of our specialty’s contribution to education scholarship is not proportional. Improved dissemination is vital to advance the field because it allows educators to build on each other’s work.Reference Sherbino 3

In 2013, Bhanji et al. created a “how-to” guide for EM education scholarship.Reference Bhanji, Cheng and Frank 4 This primer served as a launching point to inspire clinical teachers interested in engaging in scholarship. The dissemination of EM-relevant education research and scholarship has many merits, ranging from personal satisfaction and academic recognitionReference Bhanji, Cheng and Frank 4 to improved learning environments and enhanced patient care. This dissemination may galvanize a national community of practice, allowing clinician educators to learn from each other’s successes and failures.

Unfortunately, the quality of Canadian medical education scholarship has lagged behind that of our clinical research.Reference Sherbino 3 Novice academics, in particular, have had difficulty publishing within medical education: rejection rates from medical education journals can be 87% or higher, and there are not as many venues or guides to publication available to medical education researchers.Reference Norman 5 Fortunately, studies have shown that many flaws leading to manuscript rejection are preventable or fixable,Reference Bordage 6 suggesting that, through guidance and support, it may be possible to increase the dissemination of medical education research.

The purpose of this 2016 CAEP Academic Symposium consensus conference was to highlight key steps to elevate the level of Canadian EM education scholarship by providing high-yield recommendations to education scholars attempting to disseminate their research via peer-reviewed publication. Herein, we identify the key quality markers for quantitative research, qualitative research, innovation reports, reviews, and knowledge synthesis studies within medical education.

METHODS

In 2016, the Academic Section of CAEP held its second consensus conference on education. In preparation for this consensus conference, a series of four structured literature reviews were conducted to identify markers of high-quality education publications.

Search methodology

We conducted a series of scoping reviews to aggregate advice from the literature about how to best write four types of education scholarship manuscript: quantitative studies,Reference Thoma, Camorlinga and Chan 7 qualitative studies,Reference Chan, Ting and Hall 8 innovation reports,Reference Hall, Hagel and Chan 9 and reviews/synthesis works.Reference Murnaghan, Weersink and Thoma 10 These reviews resulted in distinct, genre-specific lists of quality markers related to these types of education scholarship. The number of items identified by each group ranged from 30 for innovation reportsReference Hall, Hagel and Chan 9 to 157 for quantitative research.Reference Thoma, Camorlinga and Chan 7 It was recognized that the high number of recommendations limited their practical application. A consensus process was used to identify key items.

External validation of quality indicator lists

To triangulate our findings and triage the essential markers of quality, an online survey for each category of scholarship was conducted. Four surveys (one for each topic) were published on CanadiEM.org weekly from April 4, 2016 to May 1, 2016 and emailed to the corresponding authors of key papers found in the literature reviews. We also attempted to crowd-source the expert opinions of relevant EM and medical education virtual communities of practice using social media.Reference Zhao and Zhu 11 , Reference Thoma, Paddock and Purdy 12 Specifically, the surveys were promoted on Twitter using the hashtags #MedEd (Medical Education) and #FOAMed (Free Open Access Medical education) and on the CanadiEM Facebook page. The survey also allowed participants to submit additional quality elements not identified by the thematic analysis using free text. Demographic information on survey participants was captured.

This survey allowed us to incorporate the expertise of medical educators unable to attend the consensus conference. Survey participants were asked to identify the top 25 quality markers by endorsing whether they thought each of the items should be included in the final list. Appendix A (see supplementary material) includes the surveys and demographics of survey respondents. Appendix B provides the top 25 quality markers for each category of medical education scholarship identified by the survey participants.

Consensus conference final ranking

Poster presentations containing the top 25 quality markers for the four categories of education scholarship were provided to the 2016 CAEP Academic Symposium on Education Scholarship Consensus Conference participants. In the event of a tie for the 25th item, all items tied for that position were included. Each item was listed along with the percentage of votes that it received in the online consensus process.

Using a previously published methodology for achieving a group consensus,Reference Rodriguez, Siegelman and Leone 13 - Reference Chan, Wallner and Swoboda 19 participants reviewed each of the four posters in a small group and indicated the top five most important elements in each by placing a sticker next to them. Participants were also asked to add any additional relevant items not represented within the list for each category. The key items for each category were presented to the reassembled large group of consensus conference participants for endorsement or amendment during the conference proceedings. This process was facilitated by the authors of this report.

Recommendation review

Following the consensus conference, selected recommendations for each of the four categories were reviewed. Although there were significant disparities between the consensus recommendations, four common themes were identified by the authors, which were represented in nearly every category. These recommendations were explicitly identified and expanded upon as the top four items of importance for the dissemination of all types of medical education research by the consensus conference.

RECOMMENDATIONS

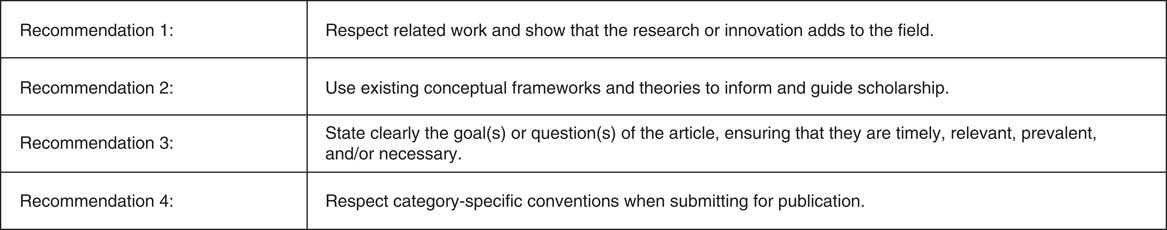

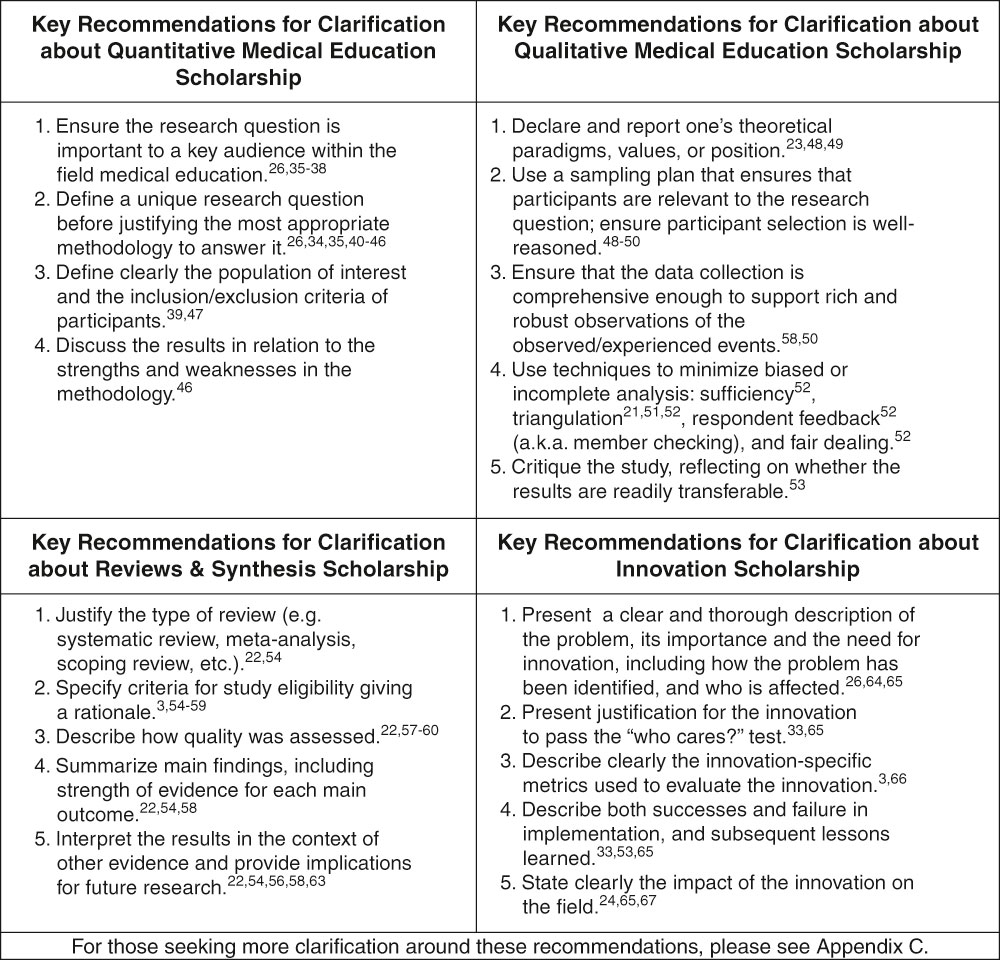

Figure 1 outlines the four thematic elements identified by the consensus conference as being important to the success of those seeking to publish their education scholarship. Figure 2 outlines the top key category-specific recommendations in each area. Further clarification of these items can be found in Appendix C (see supplementary material).

Figure 1 Key Elements of Publishable Medical Education Scholarship

Figure 2 Key Genre-based Recommendations for Medical Education Scholarship

DISCUSSION

In the Canadian EM education community, there is an increasing desire to encourage teachers and educators to generate scholarship.Reference Sherbino 3 , Reference Bhanji, Cheng and Frank 4 , Reference Sherbino, van Melle and Bandiera 22 The Education Working Group within CAEP’s Academic Section has sought to encourage the scholarly dissemination of work so that EM educators from across the country can improve their teaching techniques and educational systems. The first series of papers from the 2013 Academic Symposium 1) helped define education scholarship,Reference Sherbino, van Melle and Bandiera 22 2) described how we could support careers of educators,Reference Bandiera, Leblanc and Regehr 23 and 3) provided beginners with a guide on how to begin developing a scholarly track record.Reference Bhanji, Cheng and Frank 4 We sought to build upon this previous work by assisting educators in generating high quality education scholarship.

Because many novice educators find the traditional peer review publication processes daunting, we sought to isolate the most common stumbling blocks and provide advice to overcome them. Our proceedings during this academic symposium allowed us to view the literature guiding education scholarship through the two lenses of most of the participants: the experienced educators who have mentored novice educators through the scholarly process, and the novice or junior educator who is entering into this field for the first time. By merging these two perspectives, we have generated four overall recommendations (see Figure 1) and multiple genre-specific recommendations (see Figure 2, with clarification in Appendix C).

Recommendation 1: Respect related work and show that the research or innovation adds to the field

It is critical for education scholars to conduct a thorough, up-to-date, and critical literature search to ground their work in the existing literature.Reference Bhanji, Cheng and Frank 4 , Reference Bordage 6 , Reference McGee and Kanter 24 - Reference Kitto 26 Per Bordage, incorporating a “…thoughtful, focused, up-to-date review of the literature…”Reference Bordage 6 was one of the top five reasons for recommending acceptance of a manuscript.Reference Bordage 6 Failing to cite recent literature or citing only local examples can be a red flag for editors.Reference Monrouxe, Haidet and Ginsburg 27 Moreover, once links to previous work have been demonstrated, authors need to articulate how an innovation is novel or fills a void in the current literature.Reference Brien, Harris and Beckman 28 - Reference Sullivan, Simpson and Cook 30

Recommendation 2: Use existing conceptual frameworks and theories to inform and guide scholarship

Conceptual frameworks are ways of thinking about a study or a dilemma, a lens through which one can examine the complexities of educational or social phenomenon.Reference Bordage 31 These frameworks can act to “illuminate and magnify”Reference Schwartz, Pappas and Bashook 32 various aspects of education scholarship. The lack of a conceptual or theoretical framework led to the rejection of manuscripts submitted to major educational journals 62.2% of the time.Reference Bordage 6 An exception to this rule may be in the development of a new theory via quantitative methods such as grounded theory. Even then, however, it is important to ensure that links to previous similar work are made.Reference Charmaz 33

Recommendation 3: State clearly the goal(s) or question(s) of the manuscript, ensuring that they are timely, relevant, prevalent, and/or necessary

Having an important goal is key to successful publicationReference Yarris and Deiorio 34 and a top reason that reviewers used to explain why they recommended acceptance of papers.Reference Bordage 6 The academic community values clarity of writing.Reference Cooper and Endacott 20 , Reference Stacy and Spencer 21 Editors,Reference Monrouxe, Haidet and Ginsburg 27 reviewers,Reference Monrouxe, Haidet and Ginsburg 27 and especially readersReference Sullivan, Simpson and Cook 30 benefit from clear articulation of the intentions underpinning scholarship.Reference Yarris, Juve and Coates 35

Recommendation 4: Respect category-specific conventions when submitting for publication

The various categories of medical education scholarship have different conventions. When writing a paper, it is important that authors adhere to the language and style specific to each of these categories. Figure 2 more fully identifies key recommendations that must be considered for different categories of education scholarship, and these recommendations are more fully clarified within Appendix C.

With regards to all types of scholarship, it is crucial to explain why a particular study is important, and more specifically, to whom it is important. Many reviewers and editors will remind authors to answer two central questions: “So what?” and “Who cares?”Reference Bordage 6 The “So what?” question ensures that you have clearly made a case for why your research question is novel and interesting to the field. At times, a study may answer a new question or add a new innovative spin to previous work. Other times, a study may replicate or contradict previous findings or theories.

Junior authors should seek the mentorship of those more well-versed in an area for help when writing their manuscripts. An experienced educator may know of work that is linked conceptually but may not have been studied in the exact same context (e.g., work in intensive care unit education may be relevant to an author who is seeking to study emergency consultations skills). Linking to previous literature is of the utmost importance when reporting new findings.Reference Bhanji, Cheng and Frank 4 , Reference Bordage 6 , Reference McGee and Kanter 24 - Reference Kitto 26

Completing a thorough review of the literature is advisable, but this preparatory reading will not always lead to a publishable manuscript.Reference Murnaghan, Weersink and Thoma 10 Reviews of previous literature may not coalesce into meta-analyses or systematic reviews because the existing literature is too heterogeneous to answer a defined question.Reference Murnaghan, Weersink and Thoma 10 Clearly defined questions for synthesis works are important, but the aggregation of data must first be justifiable, as we point out in our genre-specific recommendations (see Figure 2).

Finally, we would like to advise educators that works on scholarly innovation are important; however, not every educational endeavour will be innovative. Innovation reporting requires the same amount of rigour as other forms of scholarship, with the same necessity to build upon previous work and add new ideas.Reference Hall, Hagel and Chan 9 Careful thought should be placed into whether the work of scholarship is best disseminated as an innovation report, or whether it is best delivered to other educators as a package of peer-reviewed teaching materials via new scholarly portalsReference Sherbino 3 , Reference Bhanji, Cheng and Frank 4 (such as MedEdPortal, JETem.org, EMSimCases.com, etc.).

LIMITATIONS

The main limitation of our study was that the demographic make-up of consensus conference participants was not optimal or selective. An open call for participation was made to all emergency physician members of CAEP, potentially limiting a broader inclusion of EM educators. Also, the demographics of participants indicated significant representation from very early career EM scholars (students, residents, and junior educators) who may lack significant experience in medical education scholarship. Thus, the endorsement of key steps may be influenced by limited or inexperienced consensus.

CONCLUSION

Education scholarship is imperative to advance EM education. To effectively publish and disseminate education scholarship, it is important to prevent fatal flaws.Reference Bhanji, Cheng and Frank 4 , Reference Bordage 6 , Reference McGee and Kanter 24 - Reference Kitto 26 , Reference McGaghie 36 , Reference Cook 37 Clinician educators are a prime source of innovations and research that can advance the field of medical education, and we hope that this document and its associated reviewsReference Thoma, Camorlinga and Chan 7 - Reference Murnaghan, Weersink and Thoma 10 will help foster continued education scholarship amongst the ranks of EM educators. This guide serves as a primer for both novice education scholars and clinician educators to assist in elevating EM education scholarship by attending to key steps in the publication process.

Competing interests: None declared.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2017.30