No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

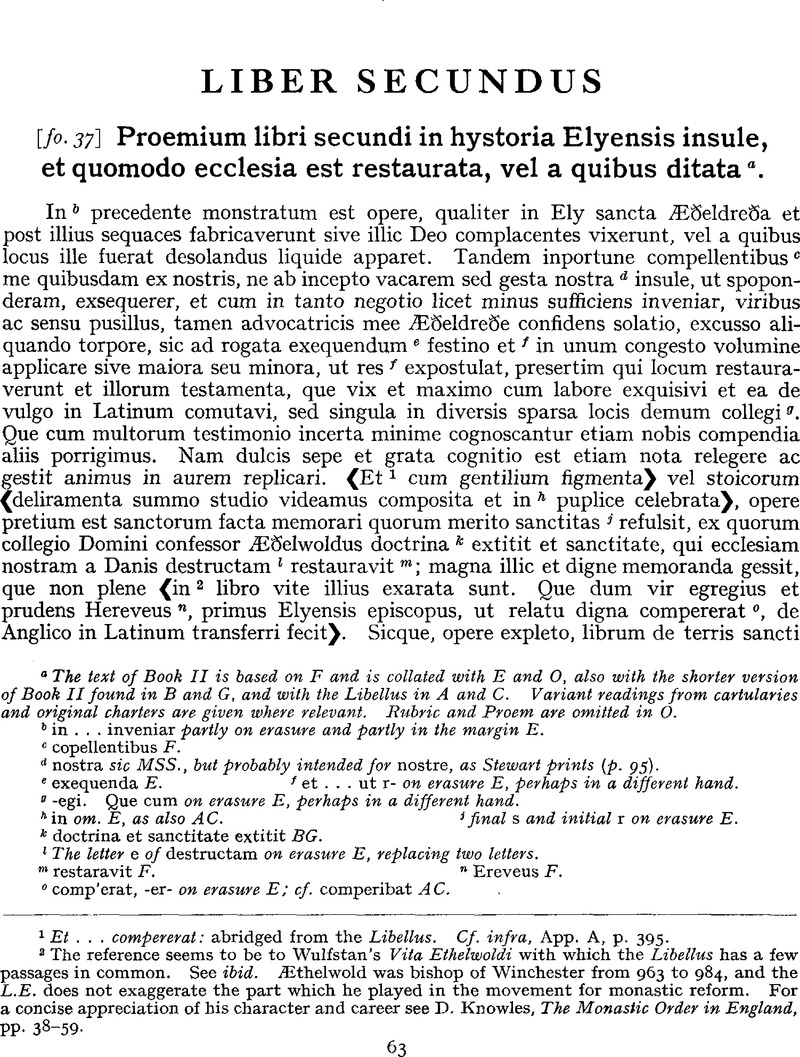

Liber Secundus

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Liber Eliensis

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Royal Historical Society 1962

References

page 63 note 1 Et … compererat: abridged from the Libellus. Cf. infra, App. A, p. 395.

page 63 note 2 The reference seems to be to Wulfstan's Vita Ethelwoldi with which the Libellus has a few passages in common. See ibid. Æthelwold was bishop of Winchester from 963 to 984, and the L.E. does not exaggerate the part which he played in the movement for monastic reform. For a concise appreciation of his character and career see D. Knowles, The Monastic Order in England, pp. 38–59.

page 64 note 1 The name given to the Libellus, the prologue of which should be compared with this proem. See supra, Introduction, p. xxxiv and infra, App. A.

page 72 note 1 For the relationship of cc. 1–4 to the Libellus and B (Book of Miracles) see supra, Introduction, p. xxxiii and infra, Apps. A and B.

page 72 note 2 restat … serviebat: cf. B (Book of Miracles).

page 73 note 1 tempore … renovavit: from Libellus, ch. 1.

page 73 note 2 ut … patebat: cf. B (Book of Miracles).

page 73 note 3 Passages within pointed brackets are from Libellus, ch. 2.

page 73 note 4 This reference to the presence of a Greek bishop in England, if true, is very interesting. I have found no evidence to corroborate it. For a critical account of the refoundation of Ely see J. A. Robinson, The Times of St Dunstan (1923). Robinson plausibly suggests—against the view expressed in The Crawford Collection of Early Charters and Documents (ed. A. S. Napier and W. H. Stevenson), no. v, pp. 10–11—that Thurstan may have ‘ derived his interest in Ely from Archbishop Oda ’, who had been granted 40 manses æt Helig in 957. According to the anonymous Life of St Oswald (Historians of the Church of York, ed. J. Raine, R.S., 1879, i, 427) Edgar also offered Ely to Oswald.

page 73 note 5 Wulfstan of Dalham is mentioned also infra, cc. 7, 18, and 35. He is probably the Wulfstan, sequipedus of Eadred's charter (ch. 28) and perhaps the Wulfstan of cc. 32 (who died before Bishop Æthelwold) as well as the Wulfstan preposituram agens of ch. 34, whose widow was named Wulfflæd. For comments on him see supra, Foreword, p. xiii; cf. Chadwick, , Studies in Anglo-Saxon Institutions (1905), p. 231Google Scholar; Robertson, Charters, pp. 124, 367.

page 74 note 1 Cf. Libellus, nam antea latebat regem.

page 74 note 2 Prov., xxi, 1.

page 74 note 3 This probably refers to annals kept at Ely. See supra, Introduction, p. xxv. The reference cannot be to Florence, who does not mention the restoration of Ely, nor to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which has the entry only in a Peterborough interpolation in E and s.a. 963. The notice of Æthelwold's appointment to the see of Winchester in that year seems a natural place for a comment on his restoration of Ely and Peterborough and need not be taken to imply that Ely was restored and Brihtnoth appointed abbot in that year rather than the traditional date of 970 (cf. Robertson, Charters, p. 346). The order of events as described in the Libellus and Edgar's charter of confirmation (infra, ch. 5) makes it difficult to say at what stage in the transactions Edgar's charters were issued, but both his extant charters (infra, cc. 9 and 39), apart from his suspect general confirmation (ch. 5), and a lost charter granting Bishampton (infra, ch. 8) are dated 970.

page 75 note 1 This sentence is modelled on Wulfstan's account (Vita Ethelwoldi, col. 91) of Æthelwold's expulsion of the clerks from Winchester (cf. Florence, s.a. 963), and as neither Wulfstan nor the Libellus speak of any expulsion of clerks in relation to Ely the L.E. tradition must be considered with suspicion. It may, however, accurately represent the local recollection, preserved in a miracle book, that in the time of Eadred the relics of St Etheldreda were in the keeping of a community of priests. See supra, Book I, cc. 41–49 and Foreword, p. xii. Eadred's charter (infra, ch. 28) cannot be taken as evidence that a community existed at Ely during his reign, since it is spurious in its surviving form, but ibid., ch. 18 records a gift to Etheldreda, which is said in ch. 24 to have been made about fifteen years ‘ antequam episcopus Æðelwoldus Ely possedisset’.

page 75 note 2 Cf. infra, Apps. A and B.

page 75 note 3 For an interesting parallel see infra, App. B.

page 75 note 4 A number of Æthelwold's gifts are entered in the inventory made in 1134, infra, Book III, ch. 50.

page 75 note 5 Libellus, ch. 4 has the same heading. Since in this and later chapters F produces a faithful copy of the Libellus, divergences are most conveniently shown with other variant readings in the textual notes from this point. Only the occasional verses, appended to some of the chapters of the Libellus, and not in F, are printed separately, infra, App. A.

page 75 note 6 The details which follow cannot be derived from the version of Edgar's charter which follows, as the latter does not give all the details. See infra, App. D, p. 414.

page 76 note 1 The compiler's authority for this statement, which does not derive from the Libellus, has not been identified. He may have based his identification of the unnamed dominus of the Libellus on no stronger evidence than his knowledge from Wulfstan's Vita Ethelwoldi (col. 86) that Æthelwold had spent part of his youth at King Æthelstan's court.

page 76 note 2 See the inventory, infra, Book III, ch. 50.

page 76 note 3 subsequens … innitatur: cf. B (Book of Miracles), infra, App. B.

page 76 note 4 This is the end of the passages which the L.E. has in common with B (Book of Miracles), except for miracle stories found in both works and Edgar's privilege which follows. The Libellus omits sicut … innitatur and Edgar's charter but adds four lines of verse, printed infra, App. A.

page 76 note 5 Date: 970.

Printed: K., no. 563; B.C.S., no. 1266, where other printed editions and the main transcripts are listed. For later confirmations see e.g. Brit. Mus., MS. Add. 9822, fos. 13–14V and Landon, Cartæ Antiquæ Rolls, no. 47 and cf. infra, ch. 92. For a facsimile version see Ordnance Survey Facsimiles, Pt. iii, no. xxxii. For a comment on the privilege see infra, App. D, p. 414.

page 79 note 1 Luc, xii, 42.

page 79 note 2 Infra, ch. 56.

page 79 note 3 Infra, ch. III.

page 79 note 4 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 5.

page 79 note 5 Hatfield, Herts. For a comment on this transaction see infra, App. D, p. 419.

page 79 note 6 Perhaps the Ordmær, who is said to have been the father of King Edgar's first wife, Æthelflæd, in William of Malmesbury (Gesta Regum, i, 180).

page 79 note 7 Æthelwine, ealdorman of East Anglia from c. 962 to 992, and his brothers, Æthelwold whom he succeeded in office, Ælfwold and Æthelsige, were sons of Æthelstan ‘ half-king ’, also ealdorman of East Anglia, who died during the reign of Edgar (see Whitelock, Wills, p. 119; Robinson, The Times of St Dunstan, p. 45 f.). Æthelwine was a firm friend of monasticism and particularly of Ramsey abbey, but did not rank as a benefactor at Ely. See Whitelock, Wills, p. 125; Robertson, Charters, p. 306; Vita S. Oswaldi, pp. 428 f., 445, 467 1, 474 f.; Ramsey Chronicle, pp. 11, 30–31.

page 80 note 1 Hemingford Abbots, Wennington and Yelling (Hunts.). See infra, App. D, p. 419.

page 80 note 2 See supra, Foreword, p. ix.

page 80 note 3 Lower and Upper Slaughter, Gloucs., where King Edward held 7 hides (Dd, i, fo. 162b, Sclostre).

page 80 note 4 Ealdorman of Mercia, d. 983 (Robertson, Charters, p. 319).

page 80 note 5 Presumably not the ealdorman who is concerned in this dispute. He could be the son of Æthelmær, ealdorman of Hampshire, who died in 982 or 983 (Whitelock, Wills, p. 126).

page 80 note 6 He succeeded Ælfhere as ealdorman of Mercia. For a note on his career see Robertson, Charters, p. 369.

page 80 note 7 This could be the Ælmær Cild who witnesses a grant of Ælfhelm Polga, in which case Ælfwold might be Ælfhelm's nephew, but the names are too common to allow identification.

page 80 note 8 The Libellus adds five lines of verse, printed infra, App. A.

page 80 note 9 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 6.

page 80 note 10 Luc, xiv, 28 f.

page 81 note 1 See infra, cc. 10, 35.

page 81 note 2 The name is preserved in Linden End, Cambs. See infra, App. D, p. 415.

page 81 note 3 Cf. infra, ch. 10, where Æthelwold is reported to have bought Linden ‘ cum c tripondiis auri’. For a comment on this equation and on the monetary units mentioned in the L.E. see supra, p. xvii.

page 81 note 4 Bishampton, Worcs. (cf. Bisantune, Dd, i, fo. 173, among the lands of the church of Worcester). See infra, App. D, p. 416.

page 81 note 5 The rhyming prose of this introductory passage is unusual for Book II. It closely resembles that of the passage introducing Edgar's Stoke charter (infra, ch. 39) and may have been taken from a collection of Edgar's charters (see ch. 39). Unless we are to assume that an Old English version existed of cc. 9 and 39, as of Edgar's privilege (ch. 5), the publica lingua must refer to the Old English description of the boundaries.

page 81 note 6 Date: 970.

Printed: K., no. 1269; B.C.S., no. 1268; Gale, Scriptores XV, i, 519; Monasticon, i, 475. For a comment on this charter see infra, App. D, p. 415.

page 82 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, cc. 7, 8, 9.

page 82 note 2 In 1066 Ely held 5 hides at Stretham, Cambs. Perhaps one of the sisters retained her share and no claim on behalf of Ely was made or has survived.

page 83 note 1 It may be that the translator has incorrectly written eius for sue and that the sisters had Leofric of Brandon for their brother as well as the other Leofric who had bequeathed them their 8 hides. This would supply a reason why the permission of Leofric of Brandon had to be sought. But by a strictly grammatical rendering eius should refer to the other Leofric whose name may have been repeated here in the Old English original. The names Leofric and Æthelflæd are too common to risk identification, but it may be significant that a Leofric of Stretham is mentioned in a document, printed as Robertson, Charters, App. II, no. IX, part of which deals with an assignment of property to Thorney and part with miscellaneous entries concerning Ely. A payment is made to Leofric of Stretham for corn and an Æthelæd gave a sum of money of which 60 pence were given to Brandon for sheep (ibid., p. 256).

page 83 note 2 Cf. supra, ch. 8.

page 83 note 3 The Libellus here adds ten lines of verse, printed infra, App. A, and with the words Evoluto post begins a new chapter, headed De eodem.

page 83 note 4 Probably Mardleybury, Herts.

page 83 note 5 For Ælfhelm Polga and his brother see infra, cc. 11, 73.

page 83 note 6 Cf. a miscellaneous document, preserved on the fly-leaf of a gospel-book once belonging to Ely (printed in B. Thorpe, Diplomatarium Anglicum Aevi Saxonid, 1865, pp. 649–51 and Earle, J., Handbook to the Land-Charters and other Saxonic Documents, 1888, p. 275Google Scholar), which gives the genealogical details on a few families of innati of Hatfield. See also supra, Foreword, p. xii.

page 84 note 1 Libellus, ch. 9, headed De eodem.

page 84 note 2 The Libellus adds eleven lines of verse, printed infra, App. A.

page 84 note 3 This chapter is copied from Libellus, cc. 10, 11, 12, 13.

page 84 note 4 Downham, Cambs., where Ely held 4 hides in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 192).

page 84 note 5 Presumably Clayhithe, which was part of 7 hides held by Ely in Horningsea, Cambs., in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 191).

page 84 note 6 Bishop Æthelwold had granted Medeshamstede (Peterborough), Oundle, and Kettering to Peterborough. Cf. Robertson, Charters, no. XXXIX, p. 73. According to Hugh Candidus the name Medeshamstede was changed to Burch soon after the refoundation of the monastery there. He inserts this information in his chronicle (ed. W. T. Mellows, 1949, p. 38) immediately after Edgar's charter of confirmation, dated 972.

page 85 note 1 Presumably not before 977, if the verdict in favour of Æthelwold ended the two-year period during which these estates were not cultivated. For a similar great meeting in London of c. 989–90, attended among others by Abbot Brihtnoth, the ealdormen Æthelwine and Brihtnoth, and several thegns connected with Ely, see Robertson, Charters, no. LXIII, p. 130.

page 85 note 2 I.e. wergild.

page 85 note 3 Libellus, ch. 11, headed De eodem.

page 85 note 4 Cf. the famous council after Edgar's death, at which Æthelwine and others spoke in defence of the monasteries, where Æthelwine's brother Ælfwold killed a man who had unjustly laid claim to some Peterborough land (Vita Oswaldi, p. 446). See supra, Foreword, p. xii.

page 85 note 5 Wansford, Northants. Cf. Robertson, Charters, p. 76, 1. 8, ‘ on æhte hundred gemote æt Wylmesforda ’. Cf. supra, Foreword, p. ix.

page 86 note 1 The Libellus adds twenty-two lines of verse, printed infra, App. A.

page 86 note 2 The Libellus here begins a new chapter, 12, but without a heading.

page 86 note 3 If this is an exact translation of the Anglo-Saxon original the descriptio of Downham cannot have been composed before the accession of Æthelred, but the translator may be expanding some such phrase as ‘ ealdorman Æthelred, the king's son ’. The reference clearly is to the future king, but the title comes is surprising, since Æthelred was only a child in his brother's reign.

page 86 note 4 Gretton, Northants. Cf. Ramsey Chron., pp. 65–66, where his son Alfnoth witnesses a sale of land. The family must have been connected with, or held land of, the family of Wulfstan of Dalham, since Alfnoth successfully challenged the gift of some land in Swaffham to Ramsey which Ælfwold, Æthelwine's brother, had bought from Æthelwoldo cognato Wulfstani de Delham. Ealdorman Æthelwine intervened on behalf of Ramsey, but after his death Alfnoth regained possession (ibid., pp. 79–80). For Æthelwold cognatus or chusin cf. infra, ch. 32. Goding may have become a monk at Ely shortly before his death (infra, ch. 26).

page 87 note 1 This place has not been identified. The domus of Siferth must have been, not in Downham, but in Linden End or Stretham where he died and where Upware lies and where his widow sold land to Ely (supra, p. 84). There is a Stow Bridge in Stretham, or perhaps there is some connection with the neighbouring parish of Wicken. But as Upware is mentioned in the boundaries of the Isle of Ely as one of the limits of one of the two Ely hundreds, the provincia ultra Upware may refer to the hundred of Witchford as distinct from that of Ely (where Siferth had already made known his intention). In this case the two Ely hundreds may not have been so much of a single unit of administration at this time as is usually thought.

page 87 note 2 Eadric, a king's reeve, presided over a plea concerning Alfnoth, son of Goding, with Ealdorman Æthelwine (Ramsey Chron., pp. 79–80), but it is doubtful whether a king's reeve could be described as one of the ealdorman's proceres.

page 87 note 3 Witness in the company of Alfnoth, son of Goding, Leofsige, son of Gode, Abbot Brihtnoth and others to a gift of land in Gretton (ibid., p. 66 and infra, ch. 33).

page 87 note 4 The use of a coloured initial at the beginning of this paragraph in the Libellus has been taken, in the numbering of chapters in C, to indicate the beginning of a new chapter, numbered 13, although there is no new heading.

page 88 note 1 Chippenham, Cambs.

page 88 note 2 An interesting reference to Cambridge customs soon after the re-conquest of the Danelaw. Cf. infra, ch. 24. On the indices in this and other Danelaw boroughs see F. M. Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 525–26.

page 88 note 3 Of these witnesses Ælfelm Polga is discussed infra, p. 143; Uvi and Oswi infra, p. 138. As Lefsius Alfwii filius follows Ælfelm Polga in this list, he may be the Lefsius whom Ramsey Chron., p. 193 calls Ælfelm's cognatus. For Alfnoth see supra, p. 86.

page 88 note 4 One of several instances in this chapter and elsewhere which show that in the Libellus the shilling is reckoned as twelve pence. See Professor Whitelock's foreword, supra, p. xvii.

page 88 note 5 Probably a brother of the priest Æthelstan, infra, p. 106, and perhaps to be identified with the Bonda who witnesses Robertson, Charters, no. LXIII, p. 131, with other thegns familiar to Ramsey and Ely. For Wacher of Swaffham see supra, ch. 33.

page 88 note 6 Perhaps Brunstan of Soham, mentioned infra, p. 89.

page 89 note 1 In the Libellus a coloured initial has, in the numbering of chapters in C, been taken to indicate the beginning of a new chapter, numbered 14, although there is no heading nor room left for one, and from this the L.E., ch. 11a is copied.

page 89 note 2 Res … videtur: cf. Sallust, Bellum Catilinae, v, 9.

page 89 note 3 Horningsea, Cambs.

page 89 note 4 Exning, Suffolk.

page 89 note 5 Soham, Cambs.

page 89 note 6 Fulbourne, Cambs.

page 89 note 7 Perhaps the homo Æurici of supra, p. 88.

page 89 note 8 See supra, Foreword, p. xvi.

page 90 note 1 For Ulf's deal in Milton see infra, ch. 31, but this debt is not mentioned there.

page 90 note 2 Freckenham, Suffolk.

page 90 note 3 Hinton Hall in Haddenham (Cambs. Place-names, p. 233).

page 90 note 4 Perhaps the Osmund Hocere of infra, ch. 12.

page 91 note 1 Even if Wine's 110 acres are included, this whole transaction accounts for only 2 hides and 14 acres of the 3 hides given to Ælfric. The Old English source probably recorded this transaction separately, without reference to these 3 hides, and it was added to the descriptio of Downham by the compiler of the Latin Libellus to explain their descent as far as possible.

page 91 note 2 This chapter is copied from Libellus, cc. 15, 16, 17.

page 91 note 3 Witchford, Cambs. See infra, ch. 14.

page 91 note 4 A Sumerlida of Stoke and a priest of the same name occur as sureties for Bishop Æthelwold in Robertson, Charters, nos. XXXIX and XL, pp. 75, 77. But the estates concerned lie in Northants. and Hunts.

page 91 note 5 The Libellus here begins a new chapter, numbered 16 and headed De eodem.

page 91 note 6 Libellus, ch. 17, headed De eodem.

page 91 note 7 Wilburton, cf. supra, ch. 8.

page 91 note 8 Libellus, ch. 18.

page 91 note 9 Æthelstan, Mann's son, was a benefactor of Ramsey and had some connection with Ælfelm Polga. An abstract of his will, including this bequest, is given in Ramsey Chron., pp. 59–61. The date of his death was recorded at Ramsey under the year 986 (Ramsey Cart., iii, 166). Cf. Whitelock, Wills, p. 134.

page 91 note 10 Wold near Witchford.

page 92 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 19.

page 92 note 2 This must be the same Witcham, as that mentioned supra, ch. 8, and part of it must have belonged to Linden, part to Witchford. Cf. also infra, cc. 17, 20.

page 92 note 3 The 3 hides are made up of 373 acres. Ely held 3 hides at Witchford in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 192).

page 92 note 4 This may be the Ælfsige who sold land in Hill and Haddenham, infra, ch. 16.

page 92 note 5 Sutton, Cambs. It may have been acquired after the death of Bishop Æthelwold, since it was not included in the Libellus. But it may merely have been omitted from surviving versions of the Libellus and have been restored to its proper place by the scribe of E. Cf. infra, ch. 24.

page 92 note 6 This chapter is copied from Libellus, cc. 20, 21, 22.

page 92 note 7 Hill and Haddenham. Cf. supra, ch. 8, and Foreword, p. ix.

page 92 note 8 Leofwine may be the same as the prepositus Leo of infra, ch. 54, who was active about this time.

page 92 note 9 Perhaps Hyll rendered into Latin.

page 92 note 10 The Libellus here begins a new chapter, numbered 21, and headed De eodem.

page 92 note 11 See supra, ch. 15.

page 92 note 12 Libellus, ch. 22, headed De eodem.

page 92 note 13 The presence of barones and urbani suggests that this is not Thetford, Cambs., but Thetford, Norfolk,

page 93 note 1 Probably not bishop of Hereford (see Robertson, Charters, p. 373), but the first bishop of Elmham after the Viking age, usually referred to as Eadulf, but called Athulf in Florence of Worcester's list of East Anglian bishops.

page 93 note 2 This chapter is copied from the Libellus, cc. 23, 24, 25, 26.

page 93 note 3 These are probably the 2 hides which Siferth (i.e. Sigeferth) of Dunham left to his daughter (supra, ch. 11), since his wife was called Wulfflæd and, if their daughter was called Sifled (i.e. Sigeflæd), she would have one name element from each parent. See also supra, Foreword, p. ix.

page 93 note 4 Libellus, ch. 24, headed De eodem.

page 93 note 5 Libellus, ch. 25, headed De eodem.

page 93 note 6 Libellus, ch. 26, headed De eodem.

page 93 note 7 Ely held 5 hides there in 1066 and Miller, Ely, p. 18, n. 1, suggests that ‘ the record may have been doctored to bring it into line with the assessment of 5 hides attributed to Wilburton in Domesday ’. But it is more likely that the translator had before him, and abbreviated, a record which omitted the names of the vendors but gave the acreage of the other lands sold. See Introduction, supra, p. lii and cf. ch. 8.

page 93 note 8 The chapter is copied from Libellus, cc. 27, 28.

page 94 note 1 Cf. infra, ch. 24, where Æscwen's gift of Stonea is said to have been made about fifteen years before Æthelwold had come into possession of Ely. If the Libellus is right in saying that Wulfstan's and Ogga's grants to St Etheldreda were also made at this time, there must have been a community of some kind there to tend her relics. See supra, ch. 3.

page 94 note 2 See supra, ch. 2.

page 94 note 3 Cf. III. Æthelred, cap. 14, ‘ And if anyone dwells undisturbed by charges and claims on his estates during his lifetime, no-one is to bring an action against his heirs after his death ’. See supra, Foreword, p. xv.

page 94 note 4 Libellus, ch. 28, without heading.

page 95 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 29, which has no heading.

page 95 note 2 This recalls the long hundred (120) of ores of 16 pence, which makes the well-known Danelaw fine of ‘ a hundred of silver ’, but in the L.E. the aureus must be equated with the mancus. See Foreword, supra, p. xvii.

page 95 note 3 This chapter is copied from Libellus, cc. 30, 31.

page 95 note 4 Libellus, ch. 31, headed De eodem.

page 95 note 5 Bishop Ægelmaer, who cannot at this date be the brother of Archbishop Stigand, is otherwise unknown.

page 96 note 1 This chapter is copied from the Libellus, ch. 32.

page 96 note 2 Wine, son of Osmund, is called de Ely supra, ch. ii. As he is there shown to be in the abbot's service, he is probably the same also as the Wine who is given a hide for his clothing infra, ch. 22.

page 96 note 3 Doddington and Wimblington, Cambs.

page 96 note 4 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 33.

page 96 note 5 The name of the abbey must have been wrongly recorded. Ramsey had no abbot of that name. The Ramsey monks did lay claim to a hide at Doddington which they no longer held in 1066, but Ramsey Chron., p. 117 states that it was given to them by Ealdorman Brihtnoth ex ictu belli morti dispositus, i.e. in 991. Thurcytel must be the abbot of Bedford (infra, ch. 31), who was related to Archbishop Oscytel and possessed estates in Cambs. and Northants. He has been plausibly identified with the Thurcytel who re-founded Crowland and Bebui must be Beeby, Leics., which he is known to have granted to Crowland (Monasticon, ii, 95; cf. Dd, i, fo. 231 Bebi). See Whitelock, D., ‘The Conversion of the Eastern Danelaw’, Saga-Book of the Viking Society, xii (1941), pp. 170, 174–75Google Scholar.

page 96 note 6 This reference to Bishop Oscytel, taken together with another infra, ch. 32, where he is acting in the capacity of bishop of Dorchester, supports the evidence that Oscytel did not relinquish Dorchester on his accession to York, but continued to hold Dorchester in plurality until his death in 971. See Whitelock, D., ‘ The Dealings of the Kings of England with Northumbria in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries ’, The Anglo-Saxons: Studies in some aspects of their History and Culture presented to Bruce Dickins, ed. Clemoes, P., 1959, p. 75Google Scholar.

page 96 note 7 See supra, ch. 21.

page 97 note 1 This chapter is copied from the Libellus, but although the chapter begins with a coloured initial and has left a space for a heading, it has not there been separately numbered.

page 97 note 2 See infra, ch. 24.

page 97 note 3 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 34. Cf. supra, ch. 18.

page 97 note 4 See supra, ch. 18.

page 97 note 5 See supra, ch. 11.

page 97 note 6 These names are discussed in Cambs. Place-names, p. 39, where they are thought to refer to the area of the fortifications on the Castle Hill.

page 98 note 1 The total number of hides acquired infra aquas et paludes et mariscum de Ely, as listed in the Libellus, adds up, not to the round figure of half a long hundred, as suggested here, but only to 57 hides 73 acres to which must be added a few unspecified acres in Hill and Haddenham (supra, ch. 15). We arrive more nearly at a round 60 hides if we add the three hides at Sutton which were given to Ely before the death of Abbot Brihtnoth and are not mentioned in the Libellus. This suggests that either the surviving versions of the Libellus are incomplete and that the Sutton chapter was included in the original, or that the 60 hide total was given in the Old English original, having been calculated from information somewhat fuller than that which the Latin Libellus contains. See Introduction, supra, p. lii.

The Libellus adds ten lines of verse, printed infra, App. A.

page 98 note 2 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 35.

page 98 note 3 Probably Taunton, Somerset.

page 98 note 4 Bluntisham, Hunts. Ely held 6½ hides there in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 204).

page 98 note 5 The claim of the sons of Boga was based on their right to inherit the lands of their maternal uncle, Tope. They held that he ought to have had Bluntesham as part of the estate of his grandmother and that it had been wrongly forfeited to the crown, although she, before her marriage, had made the required submission to Edward the Elder. But the jurors refused to accept this plea because it was claimed that she made the submission at Cambridge, and, since Edward had recovered Huntingdonshire before Cambridgeshire, a submission at Cambridge would not have been in time to save her Huntingdonshire land. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle supports the jurors on the order of events in Edward's reconquest of the eastern Danelaw. Toli must be the Toglos of A.S.C. The sons of Boga must have been young in 975, but the chronology is nevertheless possible, for marriages took place at an early age, and the eldest son of Boga could have been about twenty. He could however have claimed the land on behalf of himself and his younger brothers at a younger age than this. On the historical importance of this chapter see Professor Whitelock's foreword, supra, p. xi.

page 99 note 1 Wrongly translated from Tempsford. See A.S.C. (A), s.a. 921; Florence, s.a. 917.

page 99 note 2 This is the Brihtnoth who was killed at Maldon (see infra, ch. 62), perhaps acting here as ealdorman of Huntingdonshire. See H. M. Chadwick, Studies in Anglo-Saxon Institutions, p. 177.

page 99 note 3 See supra, Foreword, p. xvi.

page 100 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, cc. 36, 37.

page 100 note 2 According to the I.C.C. (ed. Hamilton, p. 87), Toft was assessed at 8 hides 40 acres T.R.E., but of these Ely then had 3 hides, 1 virg. and 12 acres in demesne and another hide and 10 acres, as well as a holding of ½ hide and 6 acres, held by the abbot's sokemen. In Dd, i, fo. 191b the 3 hides, 1 virg. and 12 acres and the 10 acres are listed under Hardwick, and the remaining hide and the ½ hide and 6 acres (which the I.E., p. 110 enters also under Hardwick) under Toft.

page 100 note 3 See Professor Whitelock's foreword, supra, p. xvi.

page 100 note 4 Goding of Gretton, supra, ch. 11. The Libellus here begins ch. 37, headed De eodem.

page 100 note 5 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 38.

page 100 note 6 For other references to the keeping of documents with the king's relics see Whitelock, Wills, p. 151.

page 100 note 7 Hauxton with Newton, Cambs., where Ely held 8½ hides in demesne in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 191).

page 101 note 1 Perhaps part of the 6 hides at Wangford, Suffolk, which Æthelwine gave to Ramsey (Ramsey Chron., p. 54). Cf. infra, ch. 30 and also ch. 55, where the gift of Wangford is wrongly connected with the Hatfield plea (supra, ch. 7).

page 101 note 2 Hart, Essex Charters, i, 16, suggests that this is Sproughton, Suffolk, about fifteen miles north of Holland. It probably derives its name from the Sprow who sold Holland, infra, ch. 31. The Libellus does not say how the cyrograph of Sproughton and Ramsey, Essex, came into the hands of the Ely monks; perhaps along with the gift of Holland.

page 102 note 1 Date: ? 954 × 955.

Printed: B.C.S., no. 1346.

For a comment on this charter see infra, App. D, p. 416.

page 102 note 2 Matth., x, 8.

page 102 note 3 Ely held 10 hides at Stapelford, Cambs., in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 191).

page 102 note 4 See supra, Book I, cc. 41–49.

page 102 note 5 Bardfield, referred to as a minor name in Stapleford in Essex Place-names, p. 505.

page 102 note 6 Dernford Farm and Mill (Cambs. Place-names, p. 97).

page 102 note 7 This is not true of Bishop Hervey's time. Stapleford was not one of the priory's estates in either of his charters and was restored to the monks by Bishop Nigel (infra, Book III, cc. 26, 54).

page 102 note 8 Eynesbury, Hunts. Of the two manors there one became a separate parish known as St Neot's (V.C.H. Hunts., ii, 273). See infra, App. D, p. 420.

page 103 note 1 Waresley (Hunts.) and Gamlingay (Cambs.). See infra, App. D, p. 420.

page 103 note 2 Bishop of Dorchester 975 × 979 to 1002.

page 103 note 3 Ps., lxxxii, 5.

page 104 note 1 See infra, ch. 108.

page 104 note 2 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 39.

page 104 note 3 Since cc. 28 and 29 are not in the Libellus, Alio tempore refers back to ch. 27, an earlier instalment in the dispute over Wangford.

page 104 note 4 See supra, Foreword, p. xv.

page 104 note 5 This chapter is copied from Libellus, cc. 40, 41.

page 104 note 6 Cf. infra, ch. 33, where Grim, son of Osulf, acts as a witness many years after the death of King Edgar.

page 104 note 7 In Cambs. Cf. Robertson, Charters, App. II, no. IX, pp. 253–57 for a rent which Ely derived from the fen at Fordham.

page 104 note 8 Milton, Cambs., where Ely had 12 hides in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 201b). See infra, p. 105, n. 2. Ulf was expected to find another 37 acres to balance the exchange completely (see supra, ch. 11).

page 105 note 1 Libellus, ch. 41, headed De eodem.

page 105 note 2 Abbot Thurcytel's estate cannot have been in Milton Ernest, Beds., as has been suggested (Gibbs, M., Early Charters of St Paul's, Camden Third Series, lviii, 1939, pp. xxxviii–xxxixGoogle Scholar; cf. Hart, Essex Charters, no. 22, p. 17), since it was in eadem villa as Ulf's estate which the abbot required propter introitum et exitum. It was presumably from one of these estates that Ely provided 80 swine and a swineherd for Thorney (Robertson, Charters, App. II, no. IX). For Thurcytel, abbot of Bedford and perhaps later of Crowland, see supra, ch. 22.

page 105 note 3 This transaction is discussed with reference to the constitution of St Paul's by M. Gibbs, loc. cit.

page 105 note 4 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 42.

page 105 note 5 Horningsea, Cambs. On the existence of religious communities in East Anglia in the middle of the tenth century see Whitelock, D., Saga-Book of the Viking Society, xii (1941), p. 173Google Scholar; also supra, Foreword, p. xi.

page 106 note 1 Presumably 870 when Ely is also said to have been sacked.

page 106 note 2 For a comment on the transaction recorded in cc. 32, 33, 45 and 49 see infra, App. D, pp. 420–21.

page 106 note 3 A priest Æthelstan, germanus of Archbishop Oda, occurs in Ramsey Chron., p. 49, claiming Burwell against Ramsey.

page 106 note 4 See D. Whitelock in The Anglo-Saxons: Studies … presented to Bruce Dickins, p. 79 for the interesting conjecture that this Oslac, Thored's father, is to be identified with the earl of Southern Northumbria and that the Thored who had succeeded Oslac by 979—and perhaps immediately on the latter's expulsion after the death of Edgar—might be the son mentioned here. But Professor Whitelock prefers the identification of the later earl Thored with Thored, Gunner's son.

page 106 note 5 See ibid., p. 75 where this reference to Oscytel acting in the official capacity of a bishop in Cambridgeshire during the reign of Edgar is used to support the argument that Oscytel did not relinquish Dorchester on his appointment to York. See supra, ch. 22. It also indicates that Dorchester was the diocese to which Cambridgeshire at this time belonged.

page 107 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, cc. 43, 44.

page 107 note 2 See supra, ch. 13.

page 108 note 1 Snaihvell, Cambs.

page 108 note 2 Libellus, ch. 44, without a heading.

page 108 note 3 Fen or Wood Ditton, Cambs., probably the former which belonged to Brihtnoth's wife, Ælfflæd, or her sister, at this time and which was assessed with Horningsea in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 191; Whitelock, Wills, pp. 35, 41; infra, p. 421). See supra, Foreword, p. xiii.

page 108 note 4 See supra, ch. 32.

page 109 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 45.

page 109 note 2 The descent of the 2 hides at Swaffham seems clear. They must have passed from Wulfstan, perhaps of Dalham (see supra, ch. 2), to Æthelwine, thence to King Edgar, and on to Æthelwold, who would thus have them in quarta manu. The history of Berelea is the same except that, while Wulfstan bought Swaffham, Berelea seems to have come into his possession in the course of his official duties as reeve. No reason is given why Æthelwold did not attempt to retrieve Berelea, but no estate with that name was to be connected with Ely. No minor place-name in Swaffham is recorded which could correspond to it. It may be Barley, Herts., where Chatteris held 3½ hides in 1066 (Berlai, Dd, i, fo. 136). The 2 hides at Swaffham could have lain at either Swaffham Prior or Bulbeck, Cambs., in each of which Ely held 3 hides in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 190b, 196).

page 109 note 3 A Wynsigus about this time deprived Ramsey of some land at Burwell, which borders on Swaffham (Ramsey Chron., pp. 49–50).

page 109 note 4 See supra, Foreword, p. ix.

page 109 note 5 See infra, ch. 60.

page 109 note 6 See supra, Foreword, p. xvi.

page 110 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 46.

page 110 note 2 Brandon, Suffolk, where Ely held 5 carucates in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 381b), and Livermere, Suffolk, where Guthmund held the abbey's 2 carucates in 1066 (infra, ch. 97).

page 110 note 3 Cf. the generate placitum at London, supra, p. 85 and Robertson, Charters, p. 130.

page 110 note 4 Leofric of Brandon, supra, cc. 8, 10.

page 110 note 5 Willingham, Cambs.

page 111 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 47.

page 111 note 2 A dux of this name witnesses B.C.S., nos. 674, 675, 677, in 931; 689 in 932; 702, 703 in 934 (as well as no. 701, wrongly dated 930 for 934, and a dubious text, no. 716, which, if genuine, belongs to 935 rather than 937). There is then a gap until B.C.S., no. 779 (942–46), no. 820 (947), and no. 883 (949) which he witnesses as eorl. Cf. also B.C.S., no. 882 (949), where the same name occurs without title as do others which usually have dux, and no. 812, subscribed by Acule dux. In spite of the gap in the signatures it does not follow that two men of this name are involved; for there is evidence that the large councils with magnates from all over the country, to which the early group of signatures belongs, were discontinued after about 935, and the signatures of men from the Danelaw occur only sporadically after that time. This comment is based on information from Professor D. Whitelock.

page 111 note 3 Numbered as a separate chapter, 48, in the Libellus, where a space is left for a heading.

page 111 note 4 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 49.

page 111 note 5 For a comment on cc. 37, 38, 39 and 41 see infra, App. D, p. 421.

page 111 note 6 See supra, ch. 36.

page 111 note 7 Æthelwold's translation is said to survive in the text printed by A. Schröer, Die Angelsächsischen Prosabearbeitungen der Benedictiner Regel (1888), or at least that which survives in Brit. Mus., MS. Cotton, Faustina A.x. See Ker, N., Catalogue of Manuscripts containing Anglo-Saxon (1957), pp. 194–96Google Scholar.

page 111 note 8 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 50.

page 111 note 9 See supra, ch. 37. For Wulfflasd cf. supra, ch. 34, from which it can be inferred that she was the widow of Wulfstan of Dalham.

page 111 note 10 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 51.

page 111 note 11 If this is the Ælfthryth who married Edgar, the grant to Æthelwold was presumably made before their marriage in 964 or 965.

page 112 note 1 Stoke near Ipswich. See infra, App. D, p. 416.

page 112 note 2 The language of this introductory paragraph in its rhyming prose closely resembles the paragraph introducing Edgar's Linden charter (see supra, ch. 8). This resemblance along with the reference here to exemplo precedentis privilegii may suggest that the passage derives from a collection of charters including cc. 5, 9, and 39, in that order. Unless we are to assume that an Old English version existed also of cc. 9 and 39, as for Edgar's privilege (ch. 5), the phrase gemina lingua, like publica lingua in ch. 8, must refer to the Old English description of the boundaries.

page 112 note 3 Date: 970.

Printed: K., no. 1270; B.C.S., no. 1269; Monasticon, i, 475; Gale, Scriptores XV, i, 520.

For a comment on this charter see infra, App. D, p. 416.

page 112 note 4 Ps., lxi, 11.

page 114 note 1 East Dereham, Norfolk, with its appurtenances of the hundred and a half of Mitford. This entry is not in the Libellus and may therefore represent a later tradition. East Dereham had certainly been granted to the abbey in time to be made responsible for providing a farm for the monks in the time of Abbot Leofsige (infra, ch. 84). Cf. Miller, Ely, p. 31; H. M. Cam, Liberties and Communities of Medieval England (1944), p. 185.

page 114 note 2 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 52.

page 114 note 3 Apparently identical with the 5½ hundreds of Wicklow (Cam, op. cit., p. 101), Plumesgate, Loes, Wilford, Carlford and Colneis and the Thredling of Winstow. Cf. supra, ch. 37 and Edgar's privilege, ch. 5.

page 114 note 4 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 53.

page 114 note 5 See supra, ch. 5.

page 114 note 6 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 54. It reads like an abstract of an unsuccessful plea which outlined the descent of the estate. The land at Northwold and Pulham seems to have been recovered by the time of Abbot Leofsige's allocation of farms (infra, ch. 84) and in 1066 Ely held 6 carucates and 34 sokemen at Northwold (I.E., pp. 132, 139) and 15 carucates and 4 sokemen at Pulham (I.E., p. 135).

page 114 note 7 An error for Eadred.

page 115 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 55.

page 115 note 2 Weeting, Norfolk. See infra, ch. 61. Perhaps Ægelwardus is the brother of Æthelstan, mentioned in ch. 45, which would connect him with Wulfstan of Dalham. See supra, ch. 32.

page 115 note 3 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 56.

page 115 note 4 These are presumably the 2 hides which Wulfstan had given to Æthelstan chusin. See supra, ch. 32.

page 115 note 5 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 57.

page 115 note 6 Little Gransden, Cambs. The grant must have been made sometime between Æthelwold's appointment to Winchester in 963 and Edgar's death in 975, in which period Ælfhere of Mercia, Æthelwine and Brihtnoth all sign as ealdormen. Ely held an estate there in the time of Abbot Leofsige (infra, ch. 84) and 5 hides and 1 virg. in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 191b). But cf. the suggestion by C. Hart in his forthcoming Early Charters of Eastern England that this estate includes Great Gransden (Hunts.), the subject of a grant to Thorney (C.U.L., MS. Add. 3020–21, fos. 13–13V), which might explain Ely's loss.

page 116 note 1 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 58.

page 116 note 2 Marsworth, Bucks. Ælfgifu left this estate to Edgar in her will (Whitelock, Wills, no. viii, p. 20). By 1066 the only estate there belonged to King Edward's thegn Britric (Dd, i, fo. 149b, Misseuorde).

page 116 note 3 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 59.

page 116 note 4 Identified as Kelling, Norfolk, in Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names.

page 116 note 5 This chapter is copied from Libellus, ch. 60.

page 116 note 6 See supra, ch. 32.

page 116 note 7 Chapters 49a and 49b are copied from the Libellus, where they are not numbered as separate chapters and have no heading, although a space has been left for one.

page 117 note 1 Kensworth, which was in Beds, before the Norman conquest, when it was added to Herts., not to be restored to Beds, until 1897 (V.C.H., Herts., ii, 231). There were 10 hides there in 1066 which were held of King Edward (Dd, i, fo. 136, Canesworde). Hohtune is Houghton Regis, a royal manor of 10 hides in 1066 (Dd, 1, fo. 209b). Cf. Monasticon, vi, 239, where Henry I is said to have held Houghton and Kenesworth ‘ in dominio ’.

page 117 note 2 The name survives in Armingford Hundred, Cambs., according to Cambs. Place-names, pp. 50–51 (cf. Anderson, O. S., The English Hundred Names, 1934, pp. 103–04Google Scholar). This hide and a half was presumably part of the land there given by King Edgar. See supra, ch. 4.

page 117 note 3 The Libellus ends here.

page 118 note 1 Ps., cxliv, 20.

page 118 note 2 tanta … turbati and other passages enclosed within pointed brackets to aream complent are from Osbern, Vita Dunstani, p. 112.

page 119 note 1 The following verses are written in the margin of F in a hand of the fourteenth century, with an accompanying note in a fifteenth-century hand, ‘ Isti versus scripti sunt juxta crucem argenteam in refectorio Winton ’:

Humano more crux presens edidit ore

Celitus afflata, que prespicis hie subarata,

Absit hoc ut fiat, Absit hoc ut fiat, Absit hoc ut fiat.

Judicastis bene, mutaretis non bene.

page 119 note 2 For this sentence cf. Florence, s.a. 969.

page 119 note 3 Brithnotus … tenuerunt: derived from Florence, i, 144. Cf. Vita Oswaldi, pp. 443–46.

page 119 note 4 Ps., xxxiii, 17.

page 119 note 5 Ps., cvi, 13.

page 119 note 6 Sap., x, 21; Rom., viii, 28.

page 119 note 7 Judith, vi, 15.

page 119 note 8 Ps., lxxi, 18.

page 120 note 1 The rest of the chapter is abridged from infra, ch. 144, whence the phrase illi … presumpsit is derived verbatim.

page 120 note 2 This account of the translation of St Wihtburga from Dereham on 8 July 974 occurs also in the Life in C.C.C. 393, where it follows the miracles and precedes the story of her second translation to the new church in 1106. It is included as one of the miracles in B (Book of Miracles) and may once have followed also in the Life in Trinity, O.2.1 which ends abruptly. All these accounts are probably derived from an older Life (see Introduction, supra, p. xxxvii). Cf. Bollandist Acta Sanctorum Martii, ii, 603–06; Bentham, Ely, i, 76–78; also Nova Legenda Anglie, ii, 468–70.

page 121 note 1 This reference to Dunstan's prophecy recalls the words used by Florence, i, 133, already quoted supra, Book I, ch. 42.

page 121 note 2 Cf. supra, ch. 40.

page 123 note 1 The name is preserved in Turbutsey Farm, Ely (Cambs. Place-names, p. 219).

page 123 note 2 Cf. Osbern, Vita Dunstani, p. 103: ‘ Eadgarus … ut David pietate ac fortitudine, atque ut Salomon sapientia, divitiis, gloria.’.

page 123 note 3 Probably the Leofwine prepositus of supra, ch. 16, if Leo may be taken as the latinised form of Leofwine.

page 124 note 1 Cf. supra, p. 3 and Bentham, Ely, i, 79.

page 124 note 2 Book III, cc. 78, 79.

page 124 note 3 De Situ, supra, p. 3.

page 124 note 4 This interpretation of the liberties of Ely belongs not to the tenth but to the twelfth century and is based, as the author says, on scriptis et brevibus of the abbey, belonging mainly to the periods after the Norman conquest and after the creation of a bishopric at Ely. The particular concern of the author with the archdeacon's rights in the Isle connects him with the monk Richard who tried to reclaim the abbey's rights on behalf of the new cathedral priory in a case at Rome in 1150, and suggests that the latter part of this chapter has been taken from Richard's opuscula. See Introduction, supra, pp. xxxviii–ix. A note in a hand probably of the fourteenth century adds excerpts of this chapter and the De Situ (supra, p. 2) to a copy of the ‘ discussio libertatis ’ (infra, ch. 116)—an account of an inquest into the abbey's liberties in 1080. These excerpts may be derived from the L.E. and have no independent value. But it is also possible that the liberties described in them were those discussed at Kentford and that the compiler of the L.E. found them in a memorandum together with a record of the discussio, from which he extracted the relevant portions in the De Situ and for this chapter. See Introduction, supra, p. liii.

page 125 note 1 The nature of these is discussed by Miller, Ely, pp. 30 ff. Modich may be identifiable with Mudeke which is mentioned among the fisheries of Littleport (ibid., p. 32; Cambs. Placenames, p. 213). The phrase que quarta pars est centuriatuum is applied also to Wisbech (infra, p. 144) and Miller believes that Modic may have been a ‘ court for the Wisbech district ’ and that this phrase is the Latin rendering of the Old English ferding (op. cit., pp. 32–33). For the functions and organisation of a ferding see Stenton, F. M., Engl. Hist. Rev., xxxvii, p. 227Google Scholar.

page 125 note 2 This may be derived from William I's writ, infra, p. 207.

page 125 note 3 See supra, ch. 5.

page 125 note 4 The hundred and a half of Mitford (Norfolk). See supra, ch. 40.

page 125 note 5 Described as the ‘ Trilling or Thredling of Winstow which was added to the Wicklow group ’ and as clearly the third part of Cleydon hundred (Cam, Liberties and Communities, p. 101).

page 125 note 6 This liberty was disputed by the archdeacons of Ely in the twelfth century (infra, Book III, ch. 37) and was the subject of a claim made by the priory in the time of Prior Alexander in 1150. This reference to Henry of Huntingdon therefore fits the calculations of T. Arnold that he was born before 1084 and survived into the reign of Henry II. He was the son of Nicholas whom he may have succeeded as archdeacon on his death in 1110 (Henry Hunt., Hist. Anglorum, pp. xxxi–xxxiii; infra, Book III, cc. 37, 101 and App. C).

page 126 note 1 This refers to a phrase in Edward the Confessor's charter of confirmation and the privilege of Pope Victor II, infra, cc. 92 and 93 and App. D, pp. 417–18.

page 126 note 2 O adds a chapter De obitu regis Ædgari, et quam viriliter rexit et de Edwardo et Ethelredo filiis suis, qui ei successerunt. This is made up of extracts from Florence (cited as Cronica Mariani), annals for the years, 975, 963, 959, 979, 994, 1002, 1007, and 1014, interspersed with passages from Osbern, Vita Dunstani, pp. 114–15, Henry Hunt., Hist. Anglorum (cited as Cronica Henrici), pp. 167, 174, to give a summary of Edgar's reign and the monastic foundations of Dunstan, Oswald and Æthelwold; of the succession of Edward and his martyrdom; of the succession of Æthelred, Dunstan's prophecy concerning his reign, the Danish raids and the massacre of St Brice's day; and of the death of Sweyn of Denmark. The summary includes William of Malmesbury's famous reference to the tribute of 300 wolves which King Edgar exacted from the Welsh (Gesta Regum, i, 177, but not verbatim).

page 126 note 3 I.e. the Libellus (see supra, ch. 7). The account of the Hatfield plea is clearly taken from the Latin, which it reproduces verbatim, and not from the Old English original. This chapter has probably been extracted by the compiler of Book II from some intermediate source which had itself made use of the Libellus. He is not likely himself to be transcribing from the Libellus which he has already incorporated in full and from which he would have been expected to copy the name Æ ðelwinus correctly rather than write Æwinus. Cf. two miracle stories in Book III, infra, cc. 119, 120, which, with this chapter, may have formed part of an opusculum of the monk Richard on the malefactors of Ely. See Introduction, supra, p. xxxix.

page 127 note 1 Cf. Eccl., xxxiv, 24.

page 127 note 2 Æwinus … Winningetune: from Libellus, ch. 5 (supra, ch. 7).

page 127 note 3 This reference to Wangford conflicts with the testimony of the Libellus, where Æthelwine receives this estate on a different occasion (supra, cc. 27, 30).

page 127 note 4 Ælfthryth, second wife of King Edgar. This legend is fully discussed by C. E. Wright (The Cultivation of Saga in Anglo-Saxon England, 1939, pp. 157 ff.). He prints an abstract from F (ibid., App. no. 33, pp. 278–79) with a translation into English (pp. 158–60). Cf. also Sisam, K. in Medium Aevum, xxii (1953), p. 24CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

page 128 note 1 Cf. Genesis, xxxix, on which part of this story seems to be modelled. Cf. Wright, op. cit., p. 161.

page 128 note 2 Job, xv, 35.

page 128 note 3 For the date of his death see infra, App. D, p. 411.

page 128 note 4 Ælfthryth's share in the murder of Edward the Martyr is fully discussed by Wright, op. cit., pp. 162–70, with references to the relevant sources, including this account. The wording of this passage cannot be traced back to any known source, but its contents add nothing to the legend as known to writers of the twelfth century.

page 129 note 1 For the date of his accession see infra, App. D, p. 411.

page 129 note 2 The same phrase is used in the description of Æthelred–s death, infra, ch. 79.

page 129 note 3 Date: 1004. Printed, K., no. 711; Monasticon, i, 476; Gale, Scriptores, XV, pp. 521–22. For a comment on this charter see infra, App. D, p. 417.

page 130 note 1 Thaxted, Essex. There seems no strong reason to identify Æfeliva with Æthelgifu, second wife of Ealdorman Æthelwine, as tentatively suggested by Hart (Essex Charters, no. 26, p. 18), particularly as the traditional date for the accession of Abbot Ælfsige (981) must be discarded (supra, ch. 56) and she died in 985 while Brihtnoth was still alive.

page 131 note 1 Leofwine, Æthulf's son, is one of the witnesses of Robertson, Charters, no. LXIII, p. 130, and was also a benefactor of Thorney. See Whitelock, Wills, p. 173, where it is suggested that he was the father of Leofmær of Bygrave. This grant to Ely must have been made after 1002 when Archbishop Wulfstan succeeded to York and before the death of Abbot Æsige (infra, App. D).

page 131 note 2 Kingston, Suffolk, where Ely held 2 carucates in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 386).

page 131 note 3 The Rodings, Essex, in which Ely held land, are difficult to identify. The 3 hides 45 virgates of Dd, ii, fo. 19 have been tentatively identified with Aythorp Roding, and the 2½ hides of Dd, ii, fo. 36b (to which 1 hide was attached in alia Rodinges) with High Roding (V.C.H., Essex, i, 450, 474). Cf. Miller, Ely, p. 71, n. 2, where he speaks of two Rodings, (?) Aythorp and (?) Morel; also Hart, Essex Charters, no. 35, p. 20.

page 131 note 4 Undley, Suffolk, where Ely held 1 carucate in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 382).

page 131 note 5 Lakenheath, Suffolk. Ely held 3 carucates there in 1066, but this includes the estate at Lakenheath granted by Edward the Confessor (Dd, ii, fo. 382; infra, ch. 92).

page 132 note 1 Whittlesea, Cambs., where Ely held 2 hides in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 191b) out of a total of 6 hides (Dd, i, fo. 192b, Thorney 4 hides).

page 132 note 2 Eastrea, part of the island of Whittlesea (Cambs. Place-names, p. 259).

page 132 note 3 Cottenham, Cambs., where Ely held 10 hides in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 191b). But Ely received land there also from another source, infra, p. 138.

page 132 note 4 Cf. note b, but the land of Holborn is said to have been given to the church of Ely by Bishop John Kirkby (Bentham, Ely, i, 151).

page 132 note 5 Glemsford, Suffolk, where Ely held 8 carucates in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 382).

page 132 note 6 Now represented by Starnea Dyke (Cambs. Place-names, pp. 15–17).

page 132 note 7 Probably Hatfield Regis, Essex, since Hatfield, Herts., then already belonged to Ely (se infra, ch. 64). But it is not clear why Leofwine should have been in the position to grant a far from a royal vill.

page 132 note 8 Infra, ch. 111.

page 133 note 1 Ramsey Chron., pp. 84–85 gives an abstract of the will of matrona Alfwara, genere nobilis sed fidei devotione nobilior who died in 1007 (Ramsey Cart., iii, 167) and who is probably to be identified with the Æ of this chapter.

page 133 note 2 Bridgeham (Norfolk), where Ely held 4 carucates in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 213b).

page 133 note 3 This is not easily identifiable with any of the Domesday holdings of Ely and it is not mentioned in Edward the Confessor's charter of confirmation (infra, ch. 92). Perhaps Ingham or Hingham, Norfolk (Dd, ii, 148b, 110b).

page 133 note 4 Weeting (Norfolk), where Ely held the commendation and soke over 9 liberi homines with 5½ carucates in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 162). Cf. supra, ch. 44.

page 133 note 5 Rattlesden (Suffolk), where Ely held 6 carucates in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 381b).

page 133 note 6 Mundford (Norfolk), where Ely held 3 carucates and 7 sokemen in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 213b).

page 133 note 7 See infra, Book III, cc. 78, 89.

page 133 note 8 Presumably Little Thetford, where Ely held 1 hide in 1066 as a berewick of Ely (Dd, i, fo. 191b).

page 133 note 9 The death of Brihtnoth, ealdorman from about 956, perhaps of Huntingdon and later certainly of Essex, at the battle of Maldon was made the subject of legend and song, of which the Old English poem is the most notable and the Ely tradition an interesting variant. See C. E. Wright, The Cultivation of Saga in Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 23–24; E. V. Gordon, The Battle of Maldon (revised edn. 1957) ; Vita Oswaldi, pp. 455–56. For a note on his career see Ashdown, M., English and Norse Documents (1930), pp. 274–77Google Scholar; also Whitelock, Wills, p. 106.

page 134 note 1 There is no evidence that he was ever ealdorman of Northumbria; perhaps the Ely writer saw the words ‘ on Norðhymbron ' in the poem, if he knew it, where it refers to a hostage fighting to avenge Brihtnoth's death, and drew a wrong conclusion.

page 134 note 2 Cf. Ezech., xiii, 5.

page 134 note 3 in … regno: derived from Florence, i, 144; cf. supra, ch. 51.

page 134 note 4 The names of the leaders are not given in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. They may be derived from the account of the battle in Florence, i, 149. If there is any truth in the legend that they came to avenge an earlier defeat, no record of it has survived. No raid is recorded for the year 987. The raids were not resumed until 988, and, if the compiler is thinking of 991 as the fourth year in a series, the first would fall in that year. But the only attack on which we have any information was directed against the West coast of England and cannot be considered as a prelude for the battle of Maldon. Cf. Florence, s.a. 988; also Vita Oswaldi, p. 456, which follows up the battle of 988 in Occidente immediately—transactis non plurimis mensibus—with the battle, in oriente huius inclytae regionis, in which Brihtnoth was killed. It is also possible that the Ely writer gained a false idea of two battles if he had, and could only partially understand, the Old English poem.

page 134 note 1 For a comment on the circumstances and details of Brihtnoth's bequest see infra, App. D, p. 422.

page 136 note 1 This account of Brihtnoth's death is independent of other known versions and presumably represents the local tradition. Æthelred's regnal year is probably reckoned from Florence, who places Æthelred's accession in 978 (cf. Plummer, Two Saxon Chronicles, ii, 166). The form of the dating clause combined with the phrase inter alios locatus indicates that this version of the Brihtnoth legend was compiled to form part of an account of the benefactors of Ely whose relics were translated by Prior Alexander in 1154 (cf. infra, cc. 65, 71, 72, 75, 86, 87, 99 and Introduction, supra, p. xxxviii). The beginning of this account is given as part of infra, da. 87. These relics were reported by James Bentham to have been discovered in 1769 when the North wall of the choir, in which they were then immured, was removed. His report made to the Society of Antiquaries in 1772 and a description of the bones is printed in Bentham, Ely, i, Addenda, pp. 23–24. Brihtnoth's obit is recorded in the Ely kalendar in E on 10 August, where reference is also made to his will. Cf. B. Dickins,‘ The Day of Byrhtnoth's death and other obits from a twelfth-century Ely kalendar’, Leeds Studies in English and Kindred Languages, no. vi (1937), pp. 15–17. Cf. also the kalendar in Brit. Mus., MS. Cotton, Titus D.xxvii, fos. 3–8v, where the obit is given under 11 August (discussed ibid., p. 14).

page 136 note 2 See infra, App. D, p. 422. The death of Ælfflæd and her sister were commemorated, according to the kalendar in E, on 20 May (Dickins, op. cit., p. 18).

page 136 note 3 See infra, App. D, p. 423.

page 137 note 1 Bishop of Elmham, c. 995–1001. The signature of his predecessor Theodred occurs for the last time in 995 (K., no. 688), while Æthelstan first signs in 997 (K., no. 698). He last signs in 1001 (K., no. 705), and if., no. 706, dated 1001, is witnessed by his successor.

page 137 note 2 This chapter is not reliable evidence for the abbey's immunity from episcopal control in the Anglo-Saxon period. See infra, App. C, p. 403.

page 137 note 3 Drinkstone, Suffolk, where Ely held 2 carucates in demesne in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 381b).

page 138 note 1 Infra, Book III, cc. 78, 89.

page 138 note 2 The loss of two chalices is blamed on Gocelin but neither of these is to be identified with Æthelstan's. Infra, Book III, cc. 50, 92.

page 138 note 3 See supra, ch. 62, note. His death was commemorated at Ely on 7 October (B. Dickins, op. cit., p. 22).

page 138 note 4 Uvi of Willingham, brother of Oswi, infra, ch. 67, and witness to at least two transactions concerning Ely (supra, cc. 11, 33). His death was commemorated at Ely on 16 February (Dickins, op. cit., p. 18).

page 138 note 5 Willingham, Cambs., where Ely held 7 hides in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 191b).

page 138 note 6 There is no reason to suppose that this is the same estate as one already granted there by Leofwine, Æthulf's son (supra, ch. 60). Perhaps it is to be identified with the 3½ hides less 14 acres which Oswi, sokeman of Ely, held there in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 201b).

page 138 note 7 The dates of Leofsige, ealdorman of Essex, witnessing charters from 994 to 1001 and banished 1002 (Whitelock, Wills, p. 149), establish the certain terminal dates for Uvi's will, but the limits are narrowed if Æsige did not succeed before 996 (supra, ch. 56).

page 139 note 1 Husband of Leofflæ, daughter of Ealdorman Brihtnoth (infra, ch. 88). His death was commemorated at Ely on 5 May (Dickins, op. cit., pp. 16–17, where he is identified with the Oswi who fell in battle against the Danes at Ring-mere, A.S.C., C, D, E, s.a. 1010), and Leofflæ's death on 12 October (Dickins, op. cit., p. 18).

page 139 note 2 Stetchworth, March, Kirtling, Dullingham and Swaffham (Cambs.). See infra, App. D, P. 423.

page 139 note 3 Leicester had been the centre of the diocese of the Middle Angles until the kingdom of Mercia succumbed to Danish attack. By the time of Æscwig its place had been taken by Dorchester-on-Thames. See F. M. Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed. 1947), p. 431. 4 The terminal dates of Oswi's will, 995 × 1001, are determined by the dates of Bishop Æthelstan (995–1001). Ælfric was archbishop of Canterbury from 995 to 1002 and Æscwig bishop of Dorchester from 975 × 79 to 1002.

page 139 note 5 The name is too common and occurs too frequently in the L.E. to identify him for certain with any one of the witnesses to transactions concerning Ely (e.g. supra, p. 88). Perhaps it was he who was granted land at Swaffham, where his brother held 1 virgate, for life by Abbot Brihtnoth (supra, p. no). It is probably his obit which was recorded at Ely under 24 September and that of his son on 22 July (Dickins, op. cit., p. 16).

page 140 note 1 Chedburgh, Suffolk, where Ely held 2 carucates belonging to two freemen in demesne in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 384b).

page 140 note 2 In Suffolk. Ely held 3 carucates there in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 388).

page 140 note 3 This record cannot be correct as it stands. Even the traditional date of Abbot Brihtnoth's death (981) would not allow Æsige to succeed during the reign of Edward the Martyr. Perhaps Godwin had made a bequest in favour of Ely in King Edward's time but was not admitted to the monastery until the time of Ælfsige.

page 140 note 4 Hitcham, Suffolk, where Ely held 11 carucates and 5 sokemen in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 384b), granted between 995 and 1001 during Æthelstan's pontificate.

page 140 note 5 Eadnoth, a monk at Worcester, was brought to Ramsey by Oswald, but according to the Ramsey tradition he was not made abbot until 992, when he was consecrated by Archbishop Æfheah (Ramsey Chron., p. no). The L.E. here recalls the Ramsey record, not of Eadnoth's appointment, but of the dedication of the church at Ramsey (ibid., pp. 39, 90 ff.) and the honourable mention of Æthelwine recalls his reputation at Ramsey (‘ vir Domini Oswaldus et gloriosus dux Æthelwynus ’, ibid., p. 44) rather than that at Ely (supra, ch. 55). His accession to the bishopric of Dorchester is usually placed in 1006 but charter evidence does not support 1006 as a firm date. Eadnoth signs as abbot in 1007 (K., nos. 714, 1304), and as bishop not before 1012 (K., nos. 719, 1307). He was killed in 1016, and Chatteris must therefore have been founded between 1007 and 1016. This account of its foundation was copied later into the Chatteris cartulary, Brit. Mus., MS. Cotton, Julius A.i, fos. 73–74, with no further detail (cf. Monasticon, ii, 616; V.C.H., Cambs., ii, 220). It is difficult to tell to what extent the rest of the information given about Eadnoth is independent of other sources. The note on the death of Archbishop Ælfheah in 1012 adds nothing which is not earlier recorded elsewhere (e.g. A.S.C., C, D, E, F and Florence, s.a. 1012; Osbern's Vita S. Dunstani, p. 127 and Vita S. Elphegi, printed Wharton, Anglia Sacra, ii, 112–42; Eadmer, Hist. Novorum, p. 4, which alone mentions Greenwich as the place of the martyrdom. Cf. Freeman, Norman Conquest, i, 352, 658–63). The reference chronica for Eadnoth's presence at Assandun is to Florence, i, 178, and a similar account of death and removal to Ely is given in Ramsey Chron., pp. 118–19. The whole of this chapter is probably taken from a booklet on the Ely confessors, referred to supra, ch. 62, and it was taken as the basis for the chapter De Sancto Eadnodo in Nova Legenda Anglie, App. II, pp. 540–41. Eadnoth's death was commemorated at Ely on 18 October (Dickins, op. cit., p. 21).

page 141 note 1 This account of the translation of St Ive is not related to that given in Ramsey Chron,, pp. 114–15, which has less detail. It seems to be an abstract from Goscelin's Vita S. Ivonis Episcopi (see Migne, Pat. Eat., CLV, pp. 85 ff.), which gives the date for the inventio as 1001.

page 141 note 2 ad … convenerant: from Florence, i, 178. Cf. infra, ch. 79.

page 142 note 1 Ælfgar was bishop of Elmham from 1001–1020 (A.S.C., D, Florence, s.a. 1021. He is described as ‘ Beati [Dunstani] curialis presbyter ’ in William of Malmesbury's Life of St Dunstan (Memorials of St Dunstan, p. 317). See infra, cc. 72 and 75, where it is suggested that Ælfgar may have retired to Ely in or before 1016.

page 142 note 2 For his account of Ælfgar's vision the compiler of the L.E. has used Osbern's Life of St Dunstan (Memorials of St Dunstan, pp. 120–23). The correspondence of occasional words which are not in Osbern with the Lives by Eadmer and William of Malmesbury (noted infra, in the textual notes) are probably coincidental. The same is presumably true of echoes from the Life by Adelard, but it is interesting that supra, ch. 51, also seems to imply a knowledge of this Life.

page 143 note 1 The A.D. is probably derived from Florence or A.S.C., D, where Ælfgar's death is entered s.a. 1021. A.S.C., D, states, however, that he died on the morning of Christmas Day and this, by our reckoning, is 1020. His death was commemorated at Ely on 24 December (Dickins, op. cit., p. 22). See infra, ch. 75 for the suggestion that he retired to Ely in or before 1016. See also supra, cc. 62 (notes) and 72.

page 142 note 2 Ælfelm Polga, who occurs in the Libellus (supra, p. 88). A copy of his will has survived (printed in Whitelock, Wills, no. xiii, pp. 30–34), in which this bequest is mentioned (p. 31).For a note on the date of the will (after 975 and before 1016) see ibid., p. 133, and pp. 133–34 for what is known of Ælfelm's life.

page 143 note 3 West Wratting, Cambs., where Ely held 4½ hides and 10 sokemen with 3 hides in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 190b). Ælfelm owned part of this estate by the gift of King Edgar (B.C.S., no. 1305). The 2 hides excepted from this bequest were left to Æthelric, probably the son of Ælfelm's brother (Whitelock, Wills, pp. 134–35).

page 143 note 4 Luc, xvi, 9.

page 143 note 5 For Abbot Leofsige see infra, ch. 84.

page 144 note 1 For a comment on this grant see infra, App. D, p. 424.

page 144 note 2 See supra, ch. 72.

page 144 note 3 Walpole, Norfolk.

page 144 note 4 Wisbech, Cambs., where Ely held 10 hides in 1066 (Dd, i, fo. 192). For a discussion of the ferding of Wisbech see Miller, Ely, p. 33.

page 144 note 5 All in Suffolk. In Debenham and Woodbridge Ely held small groups of sokemen in 1066 (Dd, ii, fos. 384, 388b), in Brightwell 2 carucates (Dd, ii, fo. 386). But for Woodbridge see also supra, ch. 38.

page 144 note 6 Thren., iii, 27.

page 144 note 7 If appointed at the command of King Æthelred, Ælfwine must have become bishop of Elmham in or before 1016. But we are told at the beginning of this chapter that he succeeded Ælfgar on his death and Ælfgar died in 1020. The most plausible explanation is that Ælfgar retired to Ely before 1016 (when he secured the body of Bishop Eadnoth for Ely (supra, ch. 71)) and that Ælfwine did succeed him before Æthelred died. A.S.C., D, and Florence, assuming that Ælfwine did not succeed before Ælfgar's death, would have placed his accession in 1020, and the compiler of the L.E. may have erroneously combined the Florence entry with the more precise local tradition that Ælfwine succeeded in the reign of Æthelred. Evidence from charters is not conclusive either way. K., no. 727 of 1018, witnessed by Ælfgar, is of doubtful authenticity. The signature of a Bishop Ælfwine in 1019 (K., no. 729), on the other hand, seems to advance Ælfwine's accession at least to that year. The estates given with Ælfwine show that he must not be identified with Ælfwine, son of Oswi, mentioned supra, ch. 67.

page 146 note 1 See infra, ch. 86.

page 146 note 2 St Wendred is the patron saint of March; apart from this nothing seems to be known about her (V.C.H., Cambs., iv, 119).

page 146 note 3 Date: 1008. Cadenho is Hadstock, Essex, where Ely held 2 hides in 1066 (Dd, ii, 19; Cadenhou.) In Linton (Great and Little), Ely held no land in 1066 (see Farrer, Feudal Cambridgeshire, p. 65), and no estate there is mentioned in Edward the Confessor's charter (infra, ch. 92). For Strethle (Stretley Green, Strathall) see supra, ch. 58. Printed: K., no. 725.

page 146 note 1 This claim that abbots of Ely, St Augustine's and Glastonbury from c. 970 to 1066 regularly performed a service which could be described as cancellarii dignitatem finds no confirmation elsewhere. There is no reference to such a privilege in the recorded tradition of St Augustine or Glastonbury and it is not likely to be confirmed by modern students of diplomatic. Yet the story is sufficiently detailed to warrant some kind of foundation. The last sentence of the chapter suggests that this may be the liberty, said to have been granted by Æthelred, when the abbey was trying to recover its customs after the conquest, and similarly referred to in Edward the Confessor's alleged charter of confirmation (infra, cc. 116, 92). It may be that Ely was, at least in the reign of ^Ethelred, associated with two of the most ancient English foundations in a right to have the custody of the royal sanctuary and that this privilege was referred to after the conquest by the then appropriate name of cancellarii dignitas. It is only once again mentioned explicitly in the L.E. (infra, ch. 85), in the reign of Cnut, and then in the less precise terms of ministerium in curia regis. Cf. Galbraith, V. H., Studies in the Public Records (1948), pp. 39–40Google Scholar, and for the evidence concerning ‘ chancery ’ practice in the reign of Edgar cf. Drogereit, R. in Archiv für Urkundenforschung, vol. xiii (1935)Google Scholar.

page 147 note 1 Thren., i, 1.

page 147 note 2 defunctus … sullimatus: derived from Florence, i, 172–73. The wording of Dunstan's prophecy is as found in Osbern's Vita Dunstani, pp. 114–15. Æthelred's death was commemorated at Ely on 23 April (Dickins, op. cit., p. 19).

page 148 note 1 O here adds a note on the progeny of Æthelred adapted from Ælred's Vita S. Edwardi, col. 741. The description of the accession of Edmund in 1016 is in the words of Florence, but omits his account, given at this point of the narrative, of the election of Cnut at Southampton. It is unlikely that the election of Cnut was also omitted in the version of Florence used by the compiler (which would bring it in line with the order of events as described in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (C and D, s.a. 1016), since he was acquainted with the version in Bodl. MS. 297 which —as other surviving MSS. of Florence—includes it. The compiler of the L.E. may have decided to retain the words of Florence while preferring the order of events in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. But it is more probable that he intended to extract from Florence primarily the account of the battle of Assandun and used the rest merely as a brief introduction to it, omitting everything not immediately relevant to his purpose. Cf. Introduction, supra, p. xxix.

page 148 note 1 This account of the battle of Assandun is derived from.Florence, i, 177, 175, 178, and common passages are shown within pointed brackets. Cf. Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (C, D, E), s.a. 1016. The place at which this battle was fought is usually identified with Ashingdon, Essex (Essex Placenames, p. 177) and the obit of Bishop Eadnoth in the Ely kalendar fixes its date as 18 October (B. Dickins, op. cit., pp. 20, 21). Wulfsige was the second abbot of Ramsey and the Ramsey Chronicle (p. 118) accounts for his and Eadnoth's presence at the battle in words similar to those of the L.E. ‘qui cum multis aliis religiosis personis, juxta morem Anglorum veterem, ibidem convenerant … ’

page 147 note 3 post … portionem: the passages shown within pointed brackets are from Florence, i, 179, but he does not record the manner of Edmund's death. The L.E. here gives a version of the legend found in Will. Malmesbury, Gesta Regum, i, 217–18 and Henry Hunt., Hist. Anglorum, p. 186, as well as in Walter Map, De Nugis Curialium, Dist. v, ch. 4 and Gaimar, Lestorie des Engles, 11. 4399–4428. The development of the legend is discussed by C. E. Wright, op. cit., pp. 198–205. Edmund's death was commemorated at Ely on 29 November (Dickins, op. cit., p. 19).

page 149 note 1 reginam … accepit: from Florence, i, 181, except for the second version of her name.

page 149 note 2 Listed in the inventory of 1134, infra, Book III, ch. 50.

page 149 note 3 The Ely tradition of the date of the death of Abbot Æfsige is confused. See infra, App. D, p. 411.

page 149 note 4 This reference must be to A.S.C., where the entry is found in E and F, s.a. 1022. It occurs elsewhere only in Henry Hunt., Hist. Anglorum, p. 187 and Waverley Annals, p. 178. Presumably the compiler used E or, like these others, a predecessor of it. For the suggestion that this entry in A.S.C., E, was written after the York clergy had been to Ely for the burial of Archbishop Wulfstan, see The Peterborough Chronicle (Early English Manuscripts in Facsimile, vol. iv, 1954), p. 30.

page 150 note 1 On the dates of Abbots Leofwine and Leofric see infra, App. D, p. 411.

page 150 note 2 If the references to Abbot Leofric and Cnut are correct the bequest must have been made between c. 1022 and c. 1029 and this cannot be the famous Godgifu, the wife of Earl Leofric of Mercia, as he did not die before 1057, nor the Godgifu, wife of Earl Siward mentioned in K., no. 927. Cf. Miller, Ely, p. 22, n. 10; Hart, Essex Charters, no. 44, p. 23.

page 150 note 3 High Easter, Essex, which Esgar the Staller held pro manerio in 1066 and which Ely reclaimed from his successor Geoffrey de Mandeville (Dd, ii, fo. 60). See infra, ch. 96. South Fambridge, Essex, where Ely claimed 3½ hides in 1086 (Dd, ii, fo. 97b). Terling, Essex, identified with an unnamed hide in Witham hundred which Ely claimed in 1086 (V.C.H., Essex, i, 429). Cf. Hart, op. cit., p. 23.

page 150 note 4 Date: 1022. Printed: K., no. 734; Monasticon, i, 475–76; Gale, Scnptores XV, pp. 522–23. For a comment on this charter see infra, App. D, p. 417.

page 151 note 1 Perhaps the same as the Godgifu of ch. 81. The bishop is probably Ælfric II of Elmham who succeeded sometime after 1022 and died in 1038 (Anglo-Saxon Chron. E and Florence, s.a.), and the outer limits for the date of this bequest are no more closely defined than by the probable dates of Leofric's tenure of the abbacy 1022 × 1029. For another grant of land at Barking (Suffolk) see supra, p. 144.

page 152 note 1 For the dates of Abbots Leofric and Leofsige see infra, App. D, p. 411.

page 152 note 2 Cf. Matth., xvi, 6, 11; Marc, viii, 15; Luc, xii, 1.

page 152 note 3 Both gifts are listed in the inventory of 1134, infra, Book III, ch. 50.

page 152 note 4 Infra, ch. 111.

page 152 note 5 This system of farming the demesne manors at Ely is fully discussed by Miller, Ely, pp. 38–39. It must have been imposed before the death of Cnut in 1035. Most of the estates listed here have already been mentioned as acquired before the time of Abbot Leofsige. Of the others, Stetchworth and Balsham were left to Ely before the death of Cnut (infra, ch. 88); of Marham and Colne we do not know how or when they came to Ely. An estate at Nedging (Suffolk) was left to Bury St Edmunds by Ælmaed, wife of Ealdorman Brihtnoth, but St Edmunds owned no land there in 1066 (Whitelock, Wills, pp. 38, 143) and it may have found its way to Ely. But if Brecheham is Barham (Suffolk), where Ely held 4 carucates in 1066 (Dd, ii, fo. 383b), some suspicion must attach to this version of Leofsige's allocation of farms, as Barham was not bought until the time of his successor Wulfric (infra, ch. 97). The inclusion of Wetheringsett also creates difficulties. It may have been bequeathed to Ely before the death of Cnut by Leofwaru, but what is probably the same estate is left to Ely in the will of her son Thurstan, which can be dated 1043 × 1045 (Whitelock, Wills, pp. 192–93). See infra, ch. 88. For a general comment on the system of farming out demesne manors see R. Lennard, Rural England 1086–1135 (1959), pp. 118 ff., and esp. p. 131, n. 1, where he points out that item may have dropped out of the L.E. text since the listed farms amount to only 51 weeks.

page 153 note 1 This story of Cnut's visit to Ely has often been printed, especially by C. E. Wright, op. dt., where it is discussed and in part translated (pp. 36–38 and App. no. 5, pp. 251–52) and by C. W. Stubbs, Historical Memorials of Ely Cathedral, pp. 49–52, which includes W. W. Skeat's comments on the language of the Old English song.

page 153 note 2 See supra, ch. 78.

page 154 note 1 No such charter of confirmation is known to exist.

page 154 note 2 Cant., viii, 6; Sap., vi, 19.

page 154 note 3 Marc., ix, 22.

page 154 note 4 This holding cannot be identified. Cf. O. v. Feilitzen, The Pre-Conquest Personal Names of Domesday Booh, Nomina Germanica, 3 (1937), Boddus liber homo in Essex (p. 204, Dd, ii, fo. 26b); Brictmarus, a sokeman of St Etheldreda in Suffolk (p. 195, Dd, ii, fo. 388b); Brictmarus bubba liber homo Haroldi in Suffolk (p. 195, Dd, ii, fo. 323b).

page 155 note 1 Supra, ch. 75.

page 155 note 2 This account of the foundation of Bury St Edmunds is partly derived from the version of Florence, with additions, contained in Bodl., MS. 297, p. 350, s.a. 1020 (printed in Memorials of St Edmund's Abbey, ed. T. Arnold, R.S., 1890, i, 341–42). Exact parallels are shown within pointed brackets; the rest is less close, and there is no suggestion there that any of the monks came from Ely.