No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 February 2010

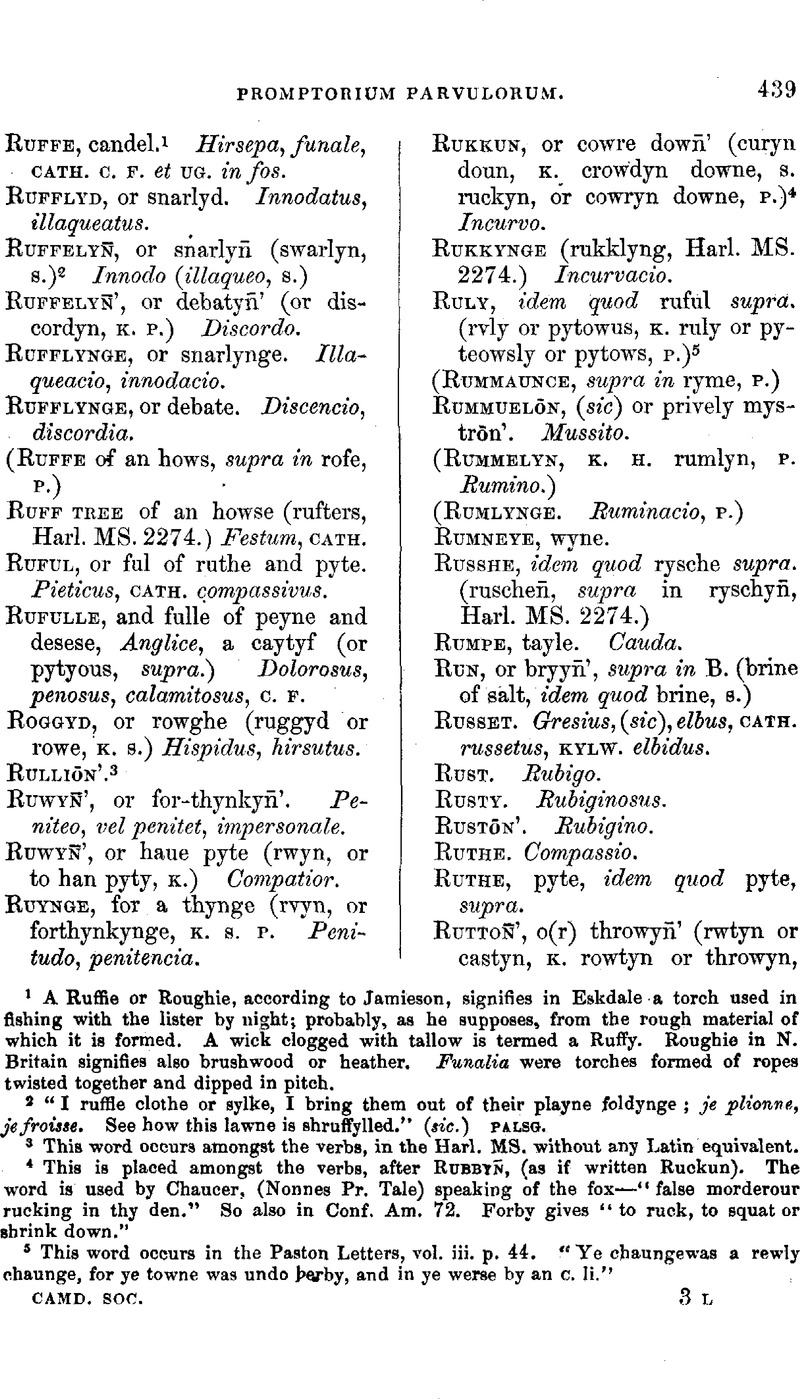

page 439 note 1 A Ruffie or Bonghie, according to Jamieson, signifies in Eskdale a torch used in fishing with the lister by night; probably, as he supposes, from the rough material of which it is formed. A wick clogged with tallow is termed a Ruffy. Roughie in N. Britain signifies also brushwood or heather, Funalia were torches formed of ropes twisted together and dipped in pitch.

page 439 note 2 “I ruffle clothe or sylke, I bring them out of their playne foldynge; je plionne, je froisse. See how this lawne is shruffylled.” (sic.) PALSG.

page 439 note 3 This word occurs amongst the verbs, in the Harl. MS. without any Latin equivalent.

page 439 note 4 This is placed amongst the verbs, after RUBBYN, (as if written Ruckun). The word is used by Chaucer, (Nonnes Pr. Tale) speaking of the fox—“false morderour rucking in thy den.” So also in Conf. Am. 72. Forby gives “to ruck, to squat or shrink down.”

page 439 note 5 This word occurs in the Paston Letters, vol. iii. p. 44. “Ye chaungewas a rewly chaunge, for ye towne was undo ðerby, and in ye werse by an c. li.”

page 440 note 1 The directions given in the Sloane MS. 73, f. 211, date late xv. cent., for making “cheverel lether of perchemyne,” may serve to throw light on this obscure word. The leather was to be “basked to and fro” in a hot solution of rock alum, “aftir take zelkis of eyren and breke hem smale in a disch as thou woldist make therof a caudel, and put these to thyn alome water, and chaufe it to a moderate hete; thaune take it doun from the fier and put it in thi eornetrey; thanne tak thi lether and basche it wel in this sabras, to it be wel dronken up into the lether.” A little flour is then to be added, the mixture again heated, and the parchment well “basked therein, and that that saberas be wel drunken up into the lether; and, if it enters not well into the lether, lay it abroad in a good long vessel that be scheld, theflesehsideupward, and poure thi sabrace al aboven the lether, and rubbe it wel yn.” It is also recommended “to late the lether ligge so still al a nyzt in his owen sabras.” In the Ancren Eiwle, edited for the Camden Society by the Rev. J. Morton, p. 364, it is said that a sick man who is wise uses abstinence, and drinks bitter sabras to recover his health: in the Latin MS. Oxon. “potat amara.” It may be from the Arabic, “Shabra, a drink.” See Notes and Queries, vol. ii. pp. 70, 204. Mr. Halliwell, in his Archaic Glossary, gives—” Sabras, salve, plaster,” which does not accord with the use of the term as above given; it has not, however, been found in any other dictionary.

page 440 note 2 Compare Oost, sacrament, Hostia, supra.

page 440 note 3 Sic, probably erroneously so written for—Satlyn, as in K. The archaism—to sag,—t o saddle, is preserved in the Herefordshire dialect.

page 441 note 1 Sic in Harl. MS., possibly erroneously so written for herbe, which is the reading i n MS. S.

page 441 note 2 A Sanop, sometimes written Savenappe—a napkin. See Sir F. Madden's edition of Syr Gawayn; also Sir Degrevant, v. 1387; Awntyrs of Arthure, v. 437; and the list of linen in the Prior's chamber, Christ Church, Canterbury, Cralba E. IV. f. 36.

page 441 note 3 Possibly the herb called “Sauce-alone, cdliavia, q. d. unicum ciborum condimentum, &c.” Skinner. It is the Erysimum alliaria.

page 441 note 4 A sausage; compare “Hilla, a tripe or a sawcister.” Ortus. “A saucestour, a saucige,” &. Harl. MS. 2257. “A salsister, hirna.” Cath. Ang. See the note on Lynke, supra, p. 306.

page 442 note 1 See the note on Matfelōn, supra, p. 329.

page 442 note 2 Mr. Halliwell gives, in his Archaic Glossary, “Scad, a carcase, a dead body.”

page 442 note 3 Sic, but probably for hefte. In K. and H., and also in Pynson's edition, we find the following distinction: Scale of an hefte (in K. capula manubrii is the Latin equivalent); and Scale of a leddyr, scalare. Compare the note on Leddyr stafe, supra, p. 293. In the translation of Vegetius, Roy. MS. 18 A. XII., “scales of ladders” are mentioned, lib. 14, c. 2. “Scale of a ladder, eschellon.” Palso. “Eschelh, a ladder or skale. eschellette, a little ladder or skale, a small step or greece.” Cotg.

page 442 note 4 Compare also Chyncery or scar(s)nesse, supra, p. 75. In the Legenda Aurea, f. 87, b., it is recorded of St. Pawlyne that she gave to the sick largely such food as they asked, “but to herself she was harde in her sekenes and skarse.” Gower treats at length of “scarsnesse,” parcimonia. “Scarse, nygarde or nat suffycient, eschars: scante or scarse, escars.” Palsg.

page 443 note 1 Chethē, MS. The terminal contraction is probably an error. Compare Schede, or schethe, infra.

page 443 note 2 Sic. Probably for Scaðe, aa also the verb, which follows,—Scayine for Scaðine; in Add. MS. 22,556, Scathin. “Damnum, harme or scathe.” Ortus.

page 443 note 3 In Pynson's edition the verbs which commence with SCH are printed SH; the nouns are printed SCH, as in the Harl. MS.

page 443 note 4 Compare Levecel, supra, p. 300.

page 443 note 5 “To schayle, degradi, et degredi.” Cath. Ang. “Schayler that gothe a wrie with his fete, boyteux. I shayle, as a man or horse dothe that gothe croked with his legges, Je vas eschays. I shayle with the fete, Jentretaille des pieds,” &c. Palsg. Compare Cotgrave, v. Gavar, Goibier, Tortipé, Esgrailler, &c. The personal name Schayler still occurs in Oxfordshire and Sussex.

page 443 note 6 Compare Pylltn, or schalyn nottys, supra, p. 399.

page 443 note 7 “Schalmesse, a pype, chalemeau.” Palsg. The shalm is figured in Musurgia, by Ott. Luscinius, &c; Comenius, Vis. World, 1659; Northumberland Household Book,&c.

page 444 note 1 Compare Delyvere, supra, p. 118.

page 444 note 2 This word is used by Wickliffe in his treatise, “Why poor priests have no Benefice,” App. to Life by Lewis, No. xix. 293; “Many times their Patrens, and other getters of country, and idle shaveldours willen look to be feasted of such Curates.”

page 444 note 3 Compare Barborehy, supra, p. 24; and Rastyr Howse, p. 424.

page 444 note 4 Compare Styrtyl, or hasty, infra, and Schytylle, p. 447.

page 444 note 5 In the Harl. MS., and also in the Winchester MS., the word Schelle is omitted, Testa being given as the Latin for Scheldrake. There can be little doubt that the readings of the MSS. H. K., and of Pynson's text, give the correction of this clerical error.

page 445 note 1 Dryngke, MS. Compare Bryllyn', or schenk drynke, supra, p. 51. Chaucer, Marchantes Tale, saya of Bacchus, “the wyn hem skinketh al aboute.” See also Rob. Glouc. p. 119; K. Alis. v. 7581; Geste of Kyng Horn, v. 374. “To skink, affundo. A skinker, pincerna, a poculis; vide Tapster.” Godldm. A. S. soencan, propinare.

page 445 note 2 Compare Cory, schepherdys howse, supra, p. 93.

page 446 note 1 Compare Astelle, supra, p. 16. “Schyde of wode, buche, moule de buches.” Palsg. “Les hasteles ðe chides) fetez alumer.” Gr. de Bibelesworth, Arund. MS. 220. A. S. seide, scindula.

page 446 note 2 Forby, in his Norfolk dialect, gives “Shim, a narrow stripe of white on a horse's face.”

page 447 note 1 Comparo Schey, as hors; supra, p. 444. Margaret Paston, writing to her husband, says, “I am aferd that Jon of Sp'h'm is so schyttyl wyttyd that he wyl sett hys gode to morgage.” Paston Letters, vol. iv. p. 58.

page 447 note 2 Compare Ondoynge of sehettellys, supra, p 365, A. S. Scyttel, a bar, bolt, or lock.

page 447 note 3 See Roggyn, or mevyn, and Roggyn, or waveryn', supra, p. 435. Forby gives the verb to Shug, signifying to shake, in the Norfolk dialect. “I shake or shogge upon one, je sache.” Palsg.

page 448 note 1 Compare Flewe, or scholde, as vessell, &c. supra p. 167. “Sholde, or full of shallowe places that a man may passe over on foote, vadosus.” Huloet, 1572.

page 448 note 2 See infra Stuk, short; Stuk or schort garment, &c, and also Scut, garment, nep-ticula.

page 448 note 3 Schoutes are mentioned in the fleet which conveyed the army of Coeur de Lion to the Holy Land. See also Piers of Fulham; Parl. Rolls, vpL iv. p. 345, &c.

page 448 note 4 See p. 84, supra, also Cadaw, p. 57, and Koo, p. 280.

page 448 note 5 Forby gives, in the Norfolk Dialect, Showing (pronounced like —ow in cow), signifying pushing with force, not the same as shoving. See Puttyn, and Puttynge, supra, pp. 417, 418.

page 448 note 6 “To shrag, castro, vide to lop.” Gouldm. “To shrag trees, artores putare.” Baret. I \n Holland's Pliny, B. xix. c. 6, it is said that in transplanting leeks the uppermost leaves should be lightly “shrigged off.”

page 449 note 1 Sic, probably for shutyn, as printed by J. Notary; shouten, by W. de Worde.

page 449 note 2 Schryve, in MS.f doubtless an error for schryne, as in K. S. P.

page 449 note 3 This word seems to have the signification of rubbish, such as broken stones, broken straw, &c. Compare ROBOWS, supra, p. 435.

page 449 note 4 Compare Fletynge of lycoure, spumacio, supra, p. 167.

page 450 note 1 Sic. This word seems to be synonymous with scourging. Compare Strype, or sehorynge with a baleys, infra, where the reading in MS. s. is scorgynge; also Wale, or strype after scornynge, infra. A Baleys is a rod or whip, virga, supra, p. 22, and is so explained as a Norfolk word by Wats, Gloss, to M. Paris,—” ex plurihus longwrihus vifninibus; qualibus utuntur padagogi severiores in scholis.” Compare zerde, baleys, injra.

page 450 note 2 “There is come a scoole of fysshe, examen.” Horm. “The youth in souls flocke and runne together.” Pox, Acts and Mon., Martyrdom of St. Agnes. A. S. sceol, a shoal.

page 451 note 1 Compare Schort or stukkyd garment, supra, p. 448; Stik, short, and Stuk or short garment, &c. infra.

page 451 note 2 Cecyn, MS. Compare Styntyn, and Swagyn, infra.

page 451 note 3 Compare Cegge, supra, p. 64, and Stare, infra.

page 451 note 4 See Coors, supra, p. 94. “Seynt of a gyrdell, tissv,” Palsg. “Ceitict, a girdle.” Cotg.

page 451 note 5 Forby gives “Seal, time or season, as hay-seal, wheat-seal, &c.” See also Ray, who mentions the word as used in Essex. So also P, Langt. p. 334: “It neghed nere metesel.” A. S. Sæl, opportunitas. Compare Barlysele, supra, p. 25, and Cele, p. 65.

page 452 note 1 Sallare, MS. “Velar, venditor minutorum comestibilium in nundinis.” Ortus.

page 452 note 2 “Seale, horse harnesBe.” Palsg. “Arquillus, an oxe bowe.” Ortus. Possibly from the French selle.

page 452 note 3 “Felix, sely or blisful: Felicio, to make sely.” Med. In a poem in Add. MS. 10053, it is said of Heaven, “There is sely endeles beyng and endeles blys.” Chaucer uses selynesse, in the sense of happiness. A. S. Sel, bene.

page 452 note 4 Compare Celwylly, supra, p. 65.

page 453 note 1 Senli, MS., doubtless an error of transcript; the reading of MS. K. is as above—Sengt.

page 453 note 2 Semy, MS., doubtless an error for seny, as the word reads in K. S. P. Compare Cent, supra, p. 6Q.

page 453 note 3 Up-drynkynge, MS. Doubtless an error of transcript for updryynge, as in MS. s., Vpdriynge. P.

page 454 note 1 Sic. Possibly written by the first hand “Servyn, as servaunte.”

page 454 note 2 Sesyn azeue (azene?) MS. This reading seems to be an error, which may be corrected by that of MS. s. “or zeve sesyn.” “I wyll sease hym in his landes,je le says-iray en ses terres.” Palsg.

page 454 note 3 Cesun, MS.

page 455 note 1 Compare Cybrede, supra, p. 77. Ray gives Sibberidge or Sibbered, signifying in Suffolk the banns of matrimony, and Sir T. Browne includes Sibrit amongst Norfolk words; see also Porby, under Sybbrit. It has been derived from A. S. Syb, cognatio, and byrht, manifestus. It has also the signification of affinity. “Affinis, viri et wxoris cognati, alyannce or sybberid.” Whitint. Gramm. “Consanguinitas, i. affinitas, sybrade.” Wilbr. Diet. “A sybredyne, consanguinitas.” Cath. Ang.

page 455 note 2 See the note on Cvyd, supra, p. 77. In the Paston Letters it is stated that Clement Paston had, when at College in 1457, “a chort blew gowne yt was reysyd, and mad of a syd gowne.” Vol. i. p. 145. “Syde as a hode, prolixus, prolixitas; Syde as a gowne, Delluxus, talaris.” Cath. Ang. “Robon, a side eassocke reaching below the knees.” Ctoe. Bishop Kennett remarks that, in Lincolnshire and in the North, the following expressions were in use,—a “side” field, i.e. long; a “side” house or mountain, i.e. high; and, by metaphor, a haughty person was called “side.” In the description of Coveitise, P. Ploughm. Vis. v. 2,857, his lolling cheeks are said to be “wel sidder than his chyn and ehyveled for elde;” and, in the Mayster of the Game, a light deer and swift in running is contrasted with such as have “side bely and flankes,” that is loose or hanging down, so as to hinder his speed. A. S. Side, longus.

page 455 note 3 This word occurs amongst the verbs, between Symentyn and Syngyn; possibly a having been written by the first hand Syngnyfyyn.

page 455 note 4 Stzbynge, MS. Doubtless an error; the word (occurring here between Syy, and Syk,) having probably been written Syhzhynge by the first hand. Compare Syzhynge, infra.

page 456 note 1 Compare Chymme Belle, supra, p. 75.

page 456 note 2 Compare Brede twyys bakyn, &c, supra, p. 48. In the Assisa Panis, which regulated the weight of bread of various kinds, it is said, “Panis vero de siminello ponderabit minus de wastello de duobus solidis, quia bis coctus est.” Stat. of Realm. “Simnell, bredde, siminiau.” Palsg. “Artocopus, panis cum lalore foetus. Placenta, a wastelle or a symnelle.”Med. Boorde, in the Breviary of Health, in regimen for the stone, says, “I refuse cakebreade, saffron breade, rye bread, leven bread, cracknels, simnels, and all manner of crustes.” &c. “Esehaudé, a kind of wigg or symnell.” Cotg.

page 457 note 1 “Diutinus, longe sythen.” ORTUS. A, S. Syddan, deinde, postea.

page 457 note 2 Compare Bhen, or bryn, or paley, supra, p. 49, and Paly of brynne, p. 379.

page 457 note 3 “Nubes, a skye.” Med. Thus in Lydgate's Minor Poems,

“Thi somerys day is nevir or seelden seyn

With som oleer hayr, but that ther is som skye.”

Compare CLOWDE, supra, p. 84, where the reading in MSS. K. H. is Clowde or skvc; Clowdy, or fulle of skyys; see also Hovyn yn þ eyre, as skyis, &c., p. 251. A. S. Skua, umbra.

page 458 note 1 See Habowe, supra, p. 228.

page 458 note 2 “Amiathon, a slyke stone (al. a sclykstone).” Med. “Linatorium, a sleke stone. Lucibricimictium, a sleyght stone.” Ortus. “A sleght stone, lamina, licinitoriuvi, luci-bricunculum.” Cath. Ang. “Slyckestone, lisse á papier, lice.” Palsg. “Sleeke stone, pierre calendrine.” Sherw. In former times polished stones, implements in form of a muller, were used to smooth linen, paper, and the like, and likewise for the operation termed calendering. Gautier de Bibelesworth says,

“Et priez la dame qe ta koyfe luche (slike)

De sa luehiere (slikingston) sur la huche.”

In directions for making buckram, &c, and for starching cloth, Sloane MS. 3548, f. 102, the finishing process is as follows: “cum lapide slyestone levifica.” Slick-stones occur i n the Tables of Custom-house Bates on Imports, 2 James I.; and about that period large stones inscribed with texts of Scripture were occasionally thus used. See Whitaker, Hist. Craven, p. 401, n. There was a specimen in the Leverian Museum. Bishop Kennett, in his Glossarial Collections, v. Slade, alludes to the use of such an appliance,— “to sleek clothes with a sleek-stone.”

page 460 note 1 Compare Gore, or slory, supra, p. 203. “To slorry or make foul, sordido.” Gouldm. “Souillé, soiled, slurried, smutched, &c; Souiller, to soyle, slurrie; Ordi, fouled, slurried, slubbered.” Cotg.

page 460 note 2 Vistio, MS. Ustio, MSS. S. P., is doubtless the true reading.

page 460 note 3 Forby gives Smeath, signifying in Norfolk an open level of considerable extent, for instance Markam Smeath (pronounced Smee,) famed in the sports of the Swaffham coursing meeting. An extensive level tract near Lynn, formerly fen, is called the Smeeth; and o t the south-west of Lynn there is a very fertile plain, celebrated as pasture for sheep, called Tylney Smeeth. A. S. Smàth, planicies.

page 461 note 1 “Testudo, a snayle, curva camera templi, curvatura, lacunar, a voute.” Med.

page 461 note 2 Compare Intrtkyn, supra, p. 262, Maelyn, p. 327, and Ruffelyn, p. 439. Palsgrave gives the verb “I snarle, I strangle in a halter, or corde, Je eslrangle: My grayhounde had almost snarled hym selfe to night in his own leesse.” See Forby's Norfolk dialect, v. “Snarl, to twist, entangle, and knot together as a skein.” Cotgrave gives “Grippets, the rufflings or snarles of ouer-twisted thread.”

page 461 note 2 “All mooris and men of Ynde be snatte nosed, as be gotis, apis, &c.” Horm. In K. Alis. v. 6447, “fuatted nose” should doubtless be read snatted.

page 461 note 4 “Instrument” ought here probably to be supplied, according to the readings K. P. “Emunctorium, ferrum cum quo candela emundatur, a snuffyng yron.” Orths. The following description of a pair of snuffers, about 1450, is found in the curious poem on the officers of a household and their duties, appended to the Boke of Curtasye, Sloane MS. 1986, f. 46, b. where, after describing various kinds of candles made by the “Chandeler,” we read that that official—

“The snof of hom dose a-way

Wyth close sesours, as I zow say,

The sesours ben schoit and rownde y close,

Wyth plate of irne vp on bose.”

page 462 note 1 “Nicto, to snoke as houndes dooth when following game.” Ortds. “Indago, to snook, to seek or search, to vent, to seek out as a hound doth.” Gouldm. Compare Bapftn, and baffynge, supra, p. 20, and Wappyn, infra.

page 462 note 2 Srowne, MS. Compare Frownyn wythe the nose, supra, p. 181, where Nasio is the reading of the Latin word, here correctly written. “Nario, i. subsannare, nares fricare, &c. to scorne or mocke.” Ortus.

page 462 note 3 Compare Ptnsone, sokke, supra, p. 400. “Socke for ones fote, ckansson.” Palsg. “Cernu, a socke without sole.” Med. “Linipedium, a hose or a socke of lynnen cloth.” Ortus. A satirical writer, t. Edw. II., says of the monks that this is the penance they do for our Lord's love,— “Hii weren sockes in here shon, and felted botea above.” Polit. Songs, p. 330.

page 462 note 4 Compare Haste, yn sodente, impetus, supra, p. 228.

page 463 note 1 Sic, probably for Soiowrnyn. Palsgrave gives— “I sejourne, I boorde in another mannes house for a tyme, or I tarye in a place for a season, Je sejourne. I sojourns,” &c. id. “Convivo, to feeste or to geste, vel simul vivere, to lyue togyder.” Ortus.

page 463 note 2 “Sole, a bowe about a beestes necke.” Palso. “Restis, a sole to tie beasts.” Gouldm. A. S. Sol, Sole, a wooden band to put round the neck of an oxe or a cow when tied up in a stall. The word is still in use in certain local dialects, as in Hereford-shire and Cheshire.

page 464 note 1 “Sollar a chambre, solier. Soller a lofte, gamier.” Palsg. “Hecteca, dioitur solarium dependens de parietibua eenaculi. Menianum, solarium, dictum a menibus, i. muris, quia muris solent addi.” Ortus. In the Boke for Travellers, the hostess says of persons arriving at an inn— “Jenette, lyghte the candell and lede them ther aboue in the solere to fore.” Compare Garotte, hey solere, supra, p. 187.

page 464 note 2 Compare Sowlynge, infra.

page 464 note 3 Compare Male Horse, genius, somarius, supra, p. 323. “Sompter horse, sommier.” P1Lsg.

page 464 note 4 Compare Towre made oonly of tymbyr, fala, infra. “Fala, Angl. a toure of tree.” Ortus. “Sommer castell of a shyppe.” Palsg. In the translation of Vegecius, Roy. MS. 8 A. XII., mention opcurs of “somer castell or bastyle” brought against the walls by an pnemy, f. 103; and of “somercastelles, bastelles, and piles,” to protect the supplies of provisions, f. 68 b.

page 464 note 5 This verb occurs in the MS. between Soposttn and Sorwyn.

page 465 note 1 Howysmete, MS. This appears doubtless an error which may be corrected by the other MSS. and Pynson's text, “houndis mete.” Palsgrave gives “Sosae, or a rewarde for houndes whan they have taken their game, hvuee.” Forby gives Soss or Suss, a mixed mess of food, a term always used in contempt, in East Anglian dialect.

page 465 note 2 Compare also Amsote, or a fole, supra, p. 11.

page 466 note 1 Sic, probably for fowle. See Solwyn, Solwtnge, &C, supra.

page 467 note 1 Compare Losange, supra, p. 313.

page 467 note 2 Compare Dtsparplyn, supra, p. 122. “To sparpylle, spergere, dividere, obstipare.” Cath. Ang “I sparkyll a broode, I sprede thynges asonder, Je disparse and je espars. Whan the sowdiers of a capitayne be sparkylled a brode, what can he do in tyme of nede.” Palsq. In the Legenda Aurea it is said of Calvary, “many sculles of hedes were there sparteled all openly.”

page 467 note 3 Splarplttnge, MS. The L after SP, is a correction added over the line.

page 467 note 4 “Libistita, fabula, fatera,” occurs in a glossary cited in Dueange. If we derive Libistica from ΛιβμςτϊΧóδ, Libyan, this term may have reference to some African writer of fables, as Apuleius, whose Metamorphoseon was familiar to the mediæval scholar. “Fabulee aut Æsopicse (sunt) aut Libysticse. Æsopicae sunt, cum animalia muta inter se sermocinasse finguntur, vel quae animam non habent, ut urbes, &c. Libysticæ autem, dum hominum cum bestiis aut bestiarum cum hominibus fingitur vocis esse commercium.” Isidor. Orig. lib. 1. c. 39.

page 468 note 1 “Cluniadiim, an hole or a spayre of a womans smoke or kyrtell.” Ortus. “Sparre of a gowne, fente de la robe.” Palsg. In the curious chapter De Vestibus, in Vocab. Roy. MS. 17 C. XVII. occur, “Manicipium, spayere; apertura, spayere; transmearium, spare-bokylle,” the latter being probably a brooch which closed the vent or fent of a dress. Compare Fente, fibulatorium, supra, p. 156. “Lacenema, a speyre; Urla, a speyrehole.” The term may have designated the openings in the dress, either at the neck, or at the sides, like pocket-holes, as seen in mediaeval costume. The Cathol. Abbrev. 1497, thus explains “cluniculum,—le pertuis qui est es vestemens des femmes iouste le coste.” Skelton gives a lament of the nun for her favourite bird— “wont to repayre and go in at my spayre,” or creep in “at my gor of my goune before.” Philip Sparow.

page 468 note 2 Amongst the Verbs. Sic MS. The noun Spelltnge may possibly be an error, corrected by other readings. Compare, however, “Spels, or broken pieces of stones coming of hewing or graving, Assnlas, micæ, segmina, secamenta.” Godldm. See also Spalle or chyppe, assulæ, supra. In Will, and Werwolf, we find Spelde, with the same signification as Spalle. See Brockett.

page 468 note 3 Compare Brokdol, supra, p. 53.

page 469 note 1 “Offendix, nodus quo liber ligatur, Angl. a knotte or clospe of a boke.” Ortus. Compare Clospb, supra, p. 83, and Ondoynge, or opynynge of schettillys, or sperellys, p. 365.

page 469 note 2 This word occurs amongst the verbs, seemingly misplaced, between Spyte mete, and Spyttyn.

page 469 note 3 Compare Aeaynye, p. 14, and Ebanye, p. 140, supra. “Spynner or spider herigne.” Palsg. See, in Trevisa's version of Bartholom. de propr. rerum, a long account of the various kinds of “Spinners”; lib. 18, c. iii.

page 469 note 4 No latin word is here given. Palsgrave has “Splent for an house, Laite; Splent, harnesse for the arme, Garde de bras.” Laite, however, signifies the milt or soft roe of a fish.

page 469 note 5 Sic, probably an error for Spoke.

page 470 note 1 Sic. The correct reading should probably be Spoylyn, or dysmembryn. Compare Dysmembryn', supra, p. 122. “I was in great danger to be spoiled by a great fierce mastiff.” Life of Adam Martindale, Chetham Soc. p. 180.

page 470 note 2 “Blictrum, id est (yest) unde—Vinum bibulit, aqua ebulit, cervisia blictrit.” Ortus.

page 470 note 3 The reading of the other MSS. and of Pynson's text is “sprawlyn.” “I spralle, as a yonge thing doth that can nat well styrre, Je crode. He spraulleth lyke a yonge padocke (grenouille). I spraule with my legges, struggell, Je me debats.” Palsg.

page 470 note 4 Forby gives Sprit, a pole to push a boat forward. A. S. Spreot, contus- In some localities the reed, juncus articulatus, is called the Spret. “Sprette, for water men, Picq.” Palsg. “Contus est quoddam instrumentum longum quo piacatores pisces scrutantur in aquis, et est genus teli quod ferrum non habet sed acutum cuspidem longum; pertica preacuta quam portant rustici loco haste,—a poll or a potte stycke.” Ortus. Compare Quantk, supra, p. 418, and Whante, infra.

page 471 note 1 Tulubacio, MS. Compare Stotynge, infra.

page 472 note 1 In the MS. Arconizo occurs here; probably an error, and properly belonging to Stakkyn, (see that verb, supra,) accidentally omitted by the second hand.

page 472 note 2 Here follows, in the Winchester MS., “Hec statela, þe standard.” Palsgrave gives “I stalke, I go softly and make great strides, Je vas a grans pas; He stalketh lyke a crane.”

page 472 note 3 Sersa, MS. Gersa, K. s. P. See the Catholicon, and Ducauge, v. Gersa, explained in the Ortus as signifying “Blatea, bleche.” Palsgrave gives “Starcheforlawne, follé fleur.” In Sloane MS. 3548, f. 102, is the following recipe, “Ad faciendum starching,—R. quantitatem furfuris et bullias in aqua munda et stet per iii. dies vel plus donee sit aqua amara vel acetosa; tune exprime aquam de furfure et in claro ejus immerge tuum pannum, s. sindonem, bokerajn, vel carde, aut aliud quod vis, et postea sicca et cum lapide lenifica,” that is, polish the surface with a slekystone. See that word, supra, p. 458.

page 472 note 4 Schydyn, MS. In the other MSS. and in Pynson's text,—Schynyn.

page 472 note 5 Palsgrave gives “Staunche greyne, an herbe,” but the substance here intended seems to have been a composition used by the mediaeval scribe, possibly like pounce, in preparing the smoothed surfaee of parchment. It was thus made: “To make stounchegrey.— Take kyddys blode and ealke and medle hem to-gedyr, and make ballys therof and bake hem in a novyn, and sel a pece for iiij.d.” Sloane MS. 3548, f. 18 b. The folhowing is from another MS. in the same collection, 2584. f. 10: “For to make staunchegreine.—Take quycke lyme and floure of whete, of iche eliche moehe, and the thride part of rosyn, and tempere hem to gidre with the white of an ey or with gote mylke, or elles with cowe mylke, and make it ryjt thicke, and tempere it to gidere til it be soft as past, and than make smalle balles therof and drie hem atte the sonne, and when it is dried hit wele serve.”

page 473 note 1 “Forwhis, i.e. bursa scriptorum.” Ortus. “Calamarium, an ynkhorne or a staunehere.” Med. MS. Cant. “Staunchon, a proppe, estancon.” Palsg.

page 473 note 2 Stache, MS. and s. staye, K. stathe, H. A. P. At Lynn are quays called “Common Staith,” “King's Staith,” &c; the name occurs frequently in Norfolk. A.S. Stæth, littus.

page 473 note 3 This word was evidently written Steffadyr, by the first hand.

page 474 note 1 Compare Lyyst of clothe, supra, p. 307; and Scheede, p. 448. “Forago, a lyste of a webbe.” Ortus. “Stamyne, estamine.” Palsg.

page 474 note 2 Sypenedde, MS. or sydeuedde (?). The true reading is, however, probably found in the other MSS.—Sydnesse, S. A. In the note on SYYD, p. 45, it has been stated that, as Bishop Kennett observes, in some dialects “Side” signifies high, as a house or a hill, and, metaphorically, a haughty person is said to be “side.”

page 474 note 3 Stekere, MS.

page 474 note 4 “Sterre slyme, lymas.” Palsq. “Assub, Angl. slyme vel quedam terra.” Ortus. “Asub, i.e. galaxia, Senderung der Stern. Galaxia, Sternenferbung oder Eeinigung.” Kulandus, Lexicon Alchemise. Lat. Germ. The singular jelly frequently found after rain is doubtless here intended; the Tremella nostoc, popularly called star-shot or star-jelly, and supposed to be the recrement of the meteors called fallen stars. See Morton, Nat. Hist. Northants, pp. 353, 356; Dr. Merret's Pinax, p. 219; Pennant, Zool. vol. ii. p. 453; Brand, Pop. Antiqu. under “Will with a wisp.” This “Spittle of the Starres” may be alluded o t in the following lines:

“The speris craketh swithe thikke,

So doth on hegge sterre stike.” K. Alis. 4437.

page 475 note 1 Compare Peerle yn the eye, glaucoma, supra, p. 394.

page 475 note 2 Fylthe, MS., fyehe, A. “Silurus, a lytell fyashe.” Ortus.

page 475 note 3 Sir Amis having lost his horse was obliged to go on foot;— “ful careful was that knight,—he stiked vp his lappes,” and trudged off on his journey. Amis and Amil. v. 988.

page 475 note 4 Styntyn or werkynge, MS. The true reading seems to be— “of”—as MS. s.

page 476 note 1 Sic. Possibly an error for sesynge, as appears by the other MSS. and P.

page 476 note 2 Presepe, MS. which signifies a manger or crib, and is probably an error for preceps, the reading in MS. s. preseps, A. Compare, Schyttylle or hasty, preceps, p. 447.

page 476 note 3 This and the following word, which occur in the verbs between Stodyyn and Stokkyn, may have been written by the first hand Stoynyn. Compare Astoynyn, supra, p. 16; also a-stoynod and a-stoynynge, ibid. Stonyynge will be found infra in its true place in alphabetical arrangement.

page 477 note 1 “Stonde a vessell, they have none” (namely the French), Palsg. “Cisternula, a stande.” Ortus. “Tine, tinne, a stand, open tub, or soe, most in use during the time of vintage, and holding about foure or five paile-fulls, and commonly borne, by a stang, between two.” Cotg. “A stand (for Ale), Tine.” Shervw.

page 477 note 2 Compare Geynecowpyn, supra, p. 189.

page 477 note 3 Compare Eoystows, and boystows garment, &c. supra, p. 42. “Stournesse, Estourdisseure; Stowre of eonversacyon, Estourdy; I make sture or rude, Jarudys; this rubbynge of your gowne agaynst the walle wyll make it sture to the syght, larudyra, &c.” Palsg. In Arund. MS 42, f. 25, bitter almonds are called “stoure—stowre almandes;” and mention is made of the “stowrhede” of mulberries, ibid. f. 64 b.

page 477 note 4 See also Sturbelare, Sturbelyn, &C, infra. This word may have been here written Storblare by the first hand.

page 478 note 1 Compare Stakerynge yn speche, supra, p. 471.

page 478 note 2 Sic. Probably written Stoþe by the first hand, as MS. A. A. S. Styth, stuth, a post, pillar.

page 478 note 3 Stragynge in tbe other MSS. and in p. Compare Strydynge, infra.

page 478 note 4 Lacombe gives the old French “Stragule, sorte d'habit dont on se couvroit le jour et la nuit, du mot latin, stragulum, couverturo de nuit, housse, oourte-pointe.” In the Exposicio verborum difficilium, MS. formerly in Chalmers's Library, wefindalso” Tragulus, i. parvum tragum quo utuntur monachi in loco camisie et lintheaminum, Anglice, strayles.” Stragula, however, whence this term seems derived, usually occur amongst bed-coverings. In the Compotus on the death of William Excetre, abbot of Bury, 1429, preserved in the Register of William Curteys his successor, there occur under Camera, Oarderoba, &o. “Bankeris,—linth',—hedschet,'—item iv. paria de strayles; item iv.paria de straylis cum signo scaccarii.” The Medulla explains “stragula, burelle, ray clothe, mottely; slragulum, id. or a strayle.”

page 478 note 5 “þe strapils of Breke, tribraca, femeralia.” Cath. Ang. Probably a kind of braces for nether garments.

page 478 note 6 ”Fragus, a strabery tre.” Ortus. “A straberi wythe, fragus.” Cath. Ang. In Arundel MS. 272, f. 48, we find the following account of the strawberry plant:— “Fragra is calde strobery wyse or freycer, hit is comyne ynoghe. The vertu therof is to hele blerede eyene and webbys in eyene and hit is gude to hele woundys. It growythe in wodys and cleuys.” Amongst ingredients for making a Drink of Antioch, Sloane MS. 100, f. 21 b. occurs “streberiwise.” A. S. Wisan, plantaria. A dish of Frasœ cost 4d. in 1265, according to an item in the Household Book of the Countess of Leicester, edited fortheRoxb. Club.

479 1 Sic. There appears to be an error here by the second hand, and also in the word following; these words should probably read—Stkeynyn. “I strayne with the hand, je estmyngs; I strayne as a hauke doth, or any syche lyke fowle or beest in theyr clawes.— Were a good glove I reede you, for your hauke strayneth harde, grippe fort; I strayne courteysie, as one.doeth that is nyce—faire trop le courtois.” PALSG.

479 2 “Cherucus, the fane of the mast, or of avayle (?sayle), quiasecundum Tentummovetur.”ORTUS. “Stremar, a baner, Estandart.” PALSG.

480 1 Compare CACCHEPOLLE or pety-seriawnte, angarims, p. 58, and MERCYMENT, multa, p. 333. Some street directory or roll of inhabitants seems to be here intended, whereby the mediaeval police might collect amerciaments, and which may have been familiarly designated, “The Street Catchpoll.” This word is not found in MS. K. In s. we read—Strete cacchpolle boke to gedyr by mercymentys. In MS. A.—Streete catchepollys book to gadir by mercymentys (no Latin.)—vacat in cop'—marginal note.

480 3 In Norfolk, according to Forby, the gullet or windpipe is still called the Stroop. Isl. strapa, gutlur. “Epiglotum, a throte boll.” ORTBS.

481 1 In MS.—sylt, which seems to be an error by the second hand; stoppyd also should possibly be read—stoffyd.

481 2 Compare PALE, garment, nepticula; also SCHORT or stukkyd garment, supra.

481 3 Compare PALE for wynys, Paxillus. In Norfolk, according to Forby, a low post put down to mark a boundary or give support to something is called a Stulp. SC.-GOTH. Stolpe, caudex. Fabyan states, in his account of Cade's rebellion, that he drew the citizens back from “the Stulpes ” in Southwark, or Bridge's foot, to the drawbridge, &c. Hall, under 4 Hen. VI. mentions likewise the “Stulpes” at London Bridge next Southwark, where there was a chain by which the way might be barred.

482 1 Forby gives Sward-pork, bacon cured in large flitches. A. S. Swserd, mitis porcina.

482 2 Compare Swamous, Craven dialect.

482 3 This may possibly be read SWELUYN, q. d. Swelwyn, or it may be only an error by the second hand for Swellyn. See BOLNYN', supra, p. 43.

482 4 “Sweam or swaim, subita wgrotatio.” GODLDM. Compare SWEYMOWSE, supra.

482 5 See Forby, u. swingel. Compare FLETLE, swyngyl, supra, p. 155. Feritormm, a battynge staffe, a batyll dur, or a betyll.” ORTUS.

483 1 Compare BEYGHTE SWERDE, Splendona, supra, p. 52, See also Roquefort, u. Lampian.

483 2 —of ful of, MS.

483 3 —fowlynge, MS. folwynge, K. s. folowinge, p.

484 1 Sic, but? more correctly Bilbio, or “bilbo—bibendo sonitum facere.” ORTUS.

483 2 These two Latin words occur in the MS. and in MS. A. after Excessus, under SURFET, being probably misplaced by the second hand, with the omission of the English terms to which they relate, which are found in the other MSS. Compare SOIURNAUNT (soioraunt, p.) commensalis, supra, p. 463; and SOIOWRYN, or go to boorde.

485 1 From the French; Lacombe gives “Tablier, table de jeu de dames, ou damier.” “Pyrgus, Anglice, a payre of tables or a checker,” ORTCS. In the Liber vocatus Equus, by Joh. de Qarlandia, Harl. MS. 1002, f. 114 b., the following line occurs, with English glosses,—“Pertica, scaccarium (checure) alea (tabelere) decius (dyce) quoque talus.” Richard Bridesall of York bequeathed, in 1392, “unum tabeler cum le menyhe.” Test. Ebor.

485 2 A small drum used in fowling to rouse the game. See TYMBYR, lytyl tabowre, infra.

485 3 Tytaly, MS.

486 1 Master Langfranc of Meleyn directs centory to be “sethed wele in stale ale, and stamped; and the juce mixed with hony, whereof iij. sponfulle eten every day fasting shall do away the glet fro the herte, and cause good talent to mete.“Palsgrave gives “Talent or lust, talent.” See Lacombe and Roquefort, v. Talaxt.

486 2 Compare SCORYN talyys, supra, p. 450. “Tayle of woode, taille de boys. Slytte this sticke in twayne, and make a payre of tayles.” PALSG. In the Northumberland Household Book it is directed to deliver to the baker “the stoke of the taill,” and the “swache ” or “swatche” to the pantler. So likewise in regard to beer, one part to be given to the brewer, the other to the butler.

486 3 Compare TOL, or custom e, infra.

486 4 Scoryn or taly, MS. An error doubtless by the second hand, corrected by the other MSS.—scoryn on tayle, K., on a taly, s. P.

486 5 It may deserve notice that in olden times the retailers of beer, and for the most part the brewers also, appear to have been females. In the note on Cukstoke, supra, p. 107, it has been stated that the trebuehetum was the punishment for the dishonest braciatrix. The Browstar (supra, p. 54,) was usually a female. In the Vision of Piers Ploughman we have a tale of the tippling at the house of “Beton the Brewesterre;” and Skelton gives a curious picture of the disorderly habits of the pandoxatrix and her customers, at a subsequent period, in his Elinour Rumming.

487 1 Forby gives the verb to Tatter, to stir actively and laboriously.

487 1 An error doubtless, by the second hand, for TA∂YNGE or TA∂INGE. See Spelman's remarks, i s t. on a peculiar manorial right in Norfolk and Suffolk called Tath; and also Forby, u. Tathe, to manure land with fresh dung by turning cattle upon it.

487 3 Horman says, “A chyldis tatches in playe shewe playnlye what they meane (mores pueri inter ludendum).” “Ofritiœ, crafty and deceytfull taches.” ELYOT. See, in the Master of Game, Sloane MS. 3501, c. xi., “Of the maners, tacches, and condyciouns of houndes.” See also P. Ploughm. Vis. 5470.

488 1 Sic, but? Ganda, gandatus, as p. Compare HAYYR, supra; Cilidum, p. 221.

488 2 Compare THUN WONGE, infra.

488 3 “Taratantariso, to tempse or ayfte. Taratantare, a tempse.” ORTUS. “Setarium, a temsyue, i. cribrum. Cervida, lignum quod portat cribrum, a temsynge staffe.” MED. In the Boke for Travellers, by Caxton, we read as follows: “Ghyselin the mande maker (corbillier) hath solde his vannea, his mandes or corffes, his temmesis to dense with (tammis).” In French, “Tamis, a searce or boulter,” &c. COTG.

488 4 Thus, in the Norfolk dialect, “Teen, trouble, vexation; to Teen,” &c PORBY. “Tenne, peine, fatigue.” LACOMBE. A. S. Teona, molestia.

489 1 “Pollis, vel pollen, est idem in tritico quod floa in siligine, the tere of floure.” Whitinton, Gramm. 1521.

489 2 In Archæol. xxxi. 336, theterm “tarage” occurs, signifying the base or groundwork of an object. Cotgrave gives Terrage in a different sense, signifying field rent. See Halliwell's Glossary, u. Terrage; earth or mould.

489 3 Compare LYTYN, or longe taryyn, and LYIYNGE, supra, p. 308.

490 1 “Calus, vas vimineum vel de salice per quod musta colantur.” CATH. “Thede, a brewars instrument.” PALSG. Forby gives “Thead, the wicker strainer placed in the mash-tub over the hole in the bottom, that the wort may run off clear;“more commonly called in Norfolk a “Fead.”

490 2 Compare WHYTHE THOENE, infra. In Heber MS. 8336, at Middle Hill, is the following recipe, xiv. cent.: “Anothur mete that hatte espyne. Nym the floures of theouethorn clenlichee i-gedeied and mak grinden in an morter al to poudre and soththen; stempre with milke of alemauns othur of corn, and soththen; do to bred othur of amydon vor to lyen, and of ayren, and lye wel wyth speces and of leues of thethorne, and stey throu floures, and soththen dresece.” In the Wicl. Version, Judges IX. 14 is thus rendered: “And all trees seiden to the ramne (ether theue thorn) come thou and be lord on us.” Ang. S. befe-born, Christ's thorn, rhamtius, vel rosa canina.

490 3 Brushwood, brambles; compare Ang. Sax.∂efe-∂orn, ut supra. In Accounts of Works at the Royal Castles, t. Hen. IV., Misc. Records of the Qu. Rem,, are payments for repairing a “gurgif'—flakes and herdles, &c.— et in iij. carect' de tenet'pro flakis et aliis necessaris ibidem faciendis, —spinas et teuette pro sepe,” &c.

490 4 Compare GOUEENYN and mesuryn in manerys and thewys, supra, p. 206, and MANER of theve, p. 324. Ang. S. Theaw, mos.

490 5 A word retained in N. Country Dialect. Ang. S. ∂igan, accipere cibum. “He haueth me do mi mete to thigge.” Havelok, v. 1373. See Jamieson.

491 1 “Dusius, i. demon, a thrusse, ∂e powke. Ravus, a thrusse, a gobelyne.” MED. GE. “Hobb Trusse, hic prepes, hic negocius.” CATH. ANG. “Lutin, a goblin, Robin Goodfellow, Hob-thrush, a spirit which playes reakes in mens houses anights. Loup-garou, a mankind wolf, &c; also a Hobgoblin, Hob-thrush, Robin Good-fellow.” COTG. See also Esprit follet, Gobelin, and Luiton. Bp. Kennett, in his Gloss. Coll. Lansd. MS. 1033, gives “A thurse, an apparition, a goblin. Lane. A Thurs-house or Thurse-hole, a hollow vault in a rock or stony hill that serves for a dwelling-house to a poor family, of which there is one at Alveton and another near Wetton Mill, co. Staff. These were looked on as enchanted holes, &c.” See also Hob-thrust, in Brockett's N. Country Glossary. Ang. S, ∂yrs, spectrum, ignis fatuus, onus. In the earlier Wieliffite version, Isai. xxxiv. 15 is thus rendered: “There shal lyn lamya, that is a thirs (thrisse in other MSS.), or a beste havende the body lie a womman and horse feet.” The word is retained in various parts of England in local dialect, and may possibly be traced in names of places, as Thursfield, Thursley, &c.

491 2 “Celtes, a cheselle or a thyxelle. Ascia, a thyxelle, or a brode axe, or a twybylle.” MED. MS. CANT. “Celtes, a chyselle or a tixil.” MED. Harl. MS..2270. A. S. ∂ixl, temo.

491 3 This term occurs in Stat. 22 Edw. IV. c. 2, in which it is enacted that fish with broken bellies are not to be mixed with tale fish, “Thokes (fish with broken bellies), Een op gesneden visch.” SEWEL. Compare Thokish, in Forby's Norfolk Glossary, and Sir T. Brown's Works, iv. 195. As a personal name we find also, in East Anglia, “Paulinus Thoke,” in an extent of the vill of Marham; it is sometimes written “Toke.” In the Winchester MS. of the Promptorium, under the letter C, occurs “Cowerde, herteles, long thoke; Vecors, &c.”

492 1 See зEETYN, infra.

492 2 Compare TOSCHAPPYD CIOTHE, infra; lilix; p. 497. Ang. Sax. scepan, forinare.

493 1 “Throte gole or throte bole, neu de la gorge, gosier.” PALSG. “Epiglotum,, a throte bolle. Frumen, the ouer parte of the throte, or the throte bolle of a man.” ORTUS. “Taurus (governeth) the necke and the throte boll ” (le ncend de dassoulz la gorge, orjg.) Shepherd's Calendar. il A throte bolle, frumen hominis est, rumen animalis est; ipoglottum.” CATH. ANG.

493 2 Compare Gaut. de Bibelesworth,—“mon haterel (nol) oue les temples (∂onewonggen).” “A thunwange, tempus.” OATH. ANG. A. Sax. ∂un-wang, tempora capitis.

493 3 Sic, pan error for thende, as in MSS. s. A. This word may be from THEEN, uigeo. Compare ON-THENDE, invalidus; and ON-THENDE, fowl, and owt cast, supra, p. 367. Halliwell gives “Unthende, abject.” “Tydy, merry, hearty.” Bp. Kennett.

494 1 TYMYN, or make a tymynge, MS. The MSS. H. S. A. and Pynson“s printed text, read Tynyn, tynynge. Tinny, a hedge, is still used in the North, and in the West of England.

494 2 Compare EYJTYNDELE, Saturn; supra, p. 137; and HALF a buschel (or tynt, K.) p. 222.

494 3 Sic MS. The first hand may have written—or wyne of Tyre. “Tyer drinke, amer brnitaige.” PALSG. “Capricke, Aligant, Tire,” occur in Andrew Boorde's Breviary of Health, c. 381.

494 4 “Turfe of a cappe or suche lyke, reiras.” PALSG.

494 5 Bishop Kennett gives “Tuttie, a posie or nosegay, in Hampshire. Tussy Mussy, a nosegay.” Lansd. MS. 1033. “A Tuttie, nosegay, posie or tuzziemuzzie, Fasciculus, sertum olfactorium.” GOGLDM. See Tosty in Jennings' W. Country Glossary; and also ' Teesty-tosty, the blossoms of cowslips collected together, tied in a globular form, and used to toss to and fro for an amusement called teesty-tosty. It is sometimes called simply a tosty.” Donne, Hist, of the Septuagint, speaks of “a girdle of flowers and tussies of all fruits intertyed,” &c.

495 1 Compare FAYTOWRYS gresse, and see the note on FAYTOWRE, supra, p. 146. The various species of Spurge (euphorbia, or the tithymalus of the old botanists) were much in esteem amongst empirics, and extraordinary effects supposed to be thereby produced, such an to make teeth fall out, hair or warts fall off, to cure leprosy, &c to kill or stupefy fish when mixed with bait. See the old Herbals, and especially Langham's Garden of Health, under Spurge and Tythimal.

495 2 Sic, doubtless for to∂id. Compare TOTHYD, infra.

495 3 Compare FROOQE, or frugge, tode, supiu, p. 180, and PADDOK, p. 376.

495 4 A penthouse. See Brockett, N. Country Glossary, u. Tee-fall, and To-fall; and Jamieson. Wyntown uses the term “to-falls ” in his account of the burning of St. Andrews' Cathedral, in 1378, denoting, as supposed, the porches of the church.

495 5 In Arund. MS. 42, f. 3, may be seen the virtues attributed to Agaric growing “by the grounde of the fir—lewede folkys callyn it tode hat.” In Norfolk, according to Forby, a fungus is called a Toad's-cap.

495 6 —made tokene, MS. make tokyn, K. s. A. P. Palsgrave gives “I token, I signyfye, &c. I token, I signe with the sygne of the crosse: I wyll token me with the crosse from their companye: je me croyseray, ” &c.

495 7 Compare TALYAGE, supra, p. 486.

496 1 —stryare, MS. styrer, A. sterrere, s.

496 2 Compare TOL, of myllarys, multa. Bp. Kennett, Glossary in Par. Ant. u. Molitvra, says that the term signified the toll taken for grinding; molitura libera was exemption from such toll, a privilege generally reserved by the lord to his own family. Palsgrave gives “I tolle, as a myller doth; je prens le tollyn.” The lord in some cases demanded toll from his tenants for grinding at his mill. See Ducange, u. Molta.

496 3 In N. country dialect to teem signifies to pour out; the participle teem or teum signifies empty—“a toom purse makes a blate merchant.”—N. C. Prov. See Ray, Brockett, &c. The noun, signifying space, leisure, appears to be thus used in the Sevyn Sages — “I sal yow tel, if I haue tome, of the Seuen Sages of Rome,” u. 4. Danish, Tom, empty, Tiimmer, to make void. Compare TAME, supra, p. 486* and TEMYM, or maken empty, p. 488. The reading of MS. s. may be (in extenso) toome or rymnyth.

496 4 “Pyrasamus, Anglice, a tongue.” OBTUS. Possibly the part of a knife technically termed the tang, to which the haft is affixed.

496 5 Forby gives “Tang, a strong flavour, generally, but not always an unpleasant one.” Fuller says of the best oil, “it hath no tast, that is no tang, but the natural gust of oyl.” Skinner derives the word, now written commonly twang, from the Dutch Tanghe, acer.

496 6 TONOWRE, of fonel, MS.—or fonel, s. A. See FONEL, mpra, p. 170. In Norfolk, according to Forby, the term in common use is Tunnel, a funnel; A.—Sax. tenel, canistrum. “Infusorium est quoddam vasculum per quod liquor infunditur in aliud vas, &c. Anglice a tonell-dysshe.” ORTUS.

497 1 TORKELARB, MS. torbelar, K. H. P.

497 2 Compare also DBVBBLYN, or torblyn watur, supra, p. 133, and DYSTURBELYN, &C. p. 123.

497 3 Compare THRE SCHAPTYD clothe, supra, p. 492. “Bilix—est pannus duobus fills stamineis contextus—a clothe with .ij. thredes.” ORTUS. Ang.-Sax. seepan, formare.

497 4 In Norfolk Tosh signifies, according to Forby, a tusk, a long curved tooth, a toshnail is a nail driven aslant.

497 5 “I toose wolle, or cotton, or suche lyke; je force de laine, and je charpie de la laine: It is a great craft to tose wolle wel.” PALSO. “Tosing, carptura; to tose wool or lyne, carpo, carmino.” GOULDM. This word is used by Gower—

“What schepe that is full of wulle. Upon his backs they tose and pulle.”—Conf. Am. Prol.

498 6 “A Tute hylle, arvisium, montariwm, specula.” CATH. ANG. “Specularis, Anglicea tutynge hylle (al. totynge). Arvisium, a tutynge hylle.” ORTUS. “Speculare, a totynpe hylle and a bekyne. Compisillum, est locus ad conspiciendum totus, a tote hulle.” MED. QR. “Totehyll, mantaignette.” PALSG. This term, of such frequent occurrence in local names in many parts of England, has been derived from Ang.-Sax. “Totian, eminere tanquam cornu in fronte.” See Dr. Bosworth's A. Saxon Diet. Wefind, however, the verb to Tote in several old writers, signifying to look out, to watch, to inspect narrowly, to look in a mirror, &c. See P. Ploughman, Spenser, Skelton, Tusser, Sec. Thus in Havelok, 2105, “He stod, and totede in at a bord;” Grafton, 577, describes a “totyng hole” in a tower, through which the Earl of Salisbury, looking out, was slain by shot from a “goon,” at the siege of Orleans in 1427. Gouldman gives the verb “to toot,” as synonymous with to look. Mr. Hartahorne, in his Salopia Antiqua, enumerates several of the numerous instances of the name Toothill, Castle Tute, Fairy Toote, &c. and the list might be largely extended. The term seems to denote a look-out or watch tower. In the version of Vegeeius, Koy. MS. 18 A. XII. f. 106, we read that “Agger is a Toothulle made of longe poles pighte vp righte and wounde about with twigges as an hegge, and fillede vp with erthe and stones, on whiche men mowe stonde and shete and caste to the walls.” In the earlier Wicl. version, 2 Kings, V. v. 7 is thus rendered; “Forsothe Dauid toke the tote hil Syon (arum Sion) that is, the citee of Dauid;” and v. 9, “Dauid dwellide in the tote hil ” (in arce) in the later version “Tour of Syon.” Again, Isai. xxi. 8, “And he criede as a leoun vp on the toothil (speaidam) of the Lord I am stondeade eontynuelly by day, and vp on my warde I am stondende alle nyjtus;” in the later version, “on the totyng place of the Lord.” Sir John Maundevile gives a curious account of the gardens and pleasaunce of the king of an Island of India, and of “a litylle Toothille with toures,” &e. where he was worn to take the air and disport. Travels, p. S78.

498 1 See strRY TOTYK, supra, p. 338, and WAWTN, or waueryn yn a myry totyr, infra. “Oscillum, genus ludi, cum funis suspenditur a trabe in quo pueri et puelle sedentes impelluntur hucetilluc,—atotoure. Petaurus, quidam ludus, atotre.” MED.GR. “Tytter-totter, a play for childre, balenchoeres.” PALSG. Porby gives Titter-cum-totter, in Norfolk dialect, to ride on the ends of a balanced plank. “Bransle, a totter, swing, or swidge, &c. Jouer l la hausse qui baisse, to play at titter totter, or at totter arse, to ride the wild mare. Saccoler, to play at titter toter or at totterarse, as children who sitting upon both ends of a long pole or timber log, supported only in the middle, lift one another up and down.” COTG See Craven Glossary, v. Merry-totter.

498 2 Compare SOMYE CASTELL, Fala, supra, p. 464.

498 3 See TOD, or toyid, supra, p. 495.

499 1 Compare tlwe, nette, Tragum, supra, p. 168. “Tramell to catche fysshe or byrdes, Trameau,.” PALSG. Tremaille, treble mailed, whence alier tremaillé, a trammell net or treble net for partridges, &c. Trameau, a kind of drag net or draw net for fish; also a trammell net for fowle.” COTG.

499 2 Compare tresawnte in a howse, Transitus, infra. In the Gesta Rom. 277, the adulterous mother confined in a dungeon thus addresses her child–“O my swete sone, a grete cause have I to sorow, and thou also, for above our hede there is a transite of men, and there the sonne shynethe in his clarté, and alle solace is there!” The Emperor's steward walking overhead hears her moan, and intercedes for her.

3 A travas or travers is explained by Sir H. Nicolas in his Glossarial Index, Privy P. Exp. of Eliz. of York, p. 259, as a kind of screen with curtains for privacy, used in chapels, halls, and other large chambers; he cites several instances of the use of the term in household accounts and other documents, to which the following may be added. In the inventory of effects of Henry V. in 1423, we find “j. travers du satin vermaille, pris viij. li. ovec ij. quisshons de velvet vermaill,” &c. probably for the king's chapel; also a “travers” for a bed: see Rot. Parl. vol. iv. pp. 227, 230. Chaucer, in the Marchantes Tale, it will be remembered, thus uses the term in the narrative of the nuptial festivity—“Men dranken, and the Travers drawe anon.” In a Survey of the manor of Hawsted, in 1681, it is stated that Sir William Drury possessed “Scitum manerii, &c. uno le mote circumjacente, uno le traves ante portam messuagii predicti, et unam magnam curiam undique bene edificatam.” Cullum's Hawsted, p. 142. Sir T. More was so greatly in favor during 20 years of his life at the court of Henry VIII. that, as Roper says, “a good part thearof used the kinge uppon holie daies, when he had donne his owne devotions, to sende for him into his traverse, and theare, sometimes in matters of Astronomy, Geometry, Divinity, and suche other faculties, and sometimes of his worldly affaires, to sit and converse with him.” In this and other instances a traverse seems to have been a kind of state pew, or closet. So like wise we read that when Queen Elizabeth visited Cambridge in 1564, on the south side of the chapel at King's College was hung a rich Travas of crimson velvet for the queen's majesty; and when she entered the chapel, desiring to pray privately, she “went into her Travys, under a canopy.” Le Keux, Mem. of Camb. vol. ii. King's Coll. pp. 20, 21. Thus also Fabyan relates that the king coming to St. Paul's “kneled in a trauers purueyed for hym” near the altar. Chron. 9 Hen. VI. A Traverse is explained in the Glossary of Architecture as having been a screen with curtains, in a hall, chapel, or large chamber.

500 1 A trave for to scḥo horse in, Ferratorium.” cath. ang. This term, it will be remembered, is used by Chaucer, in his description of the Miller's young wife, where he says— “she sprong as a colt in a traue” (rhyming to save). Miller's Tale. This is doubtless the frame used for confining an unruly horse whilst being shod. According to Forby, a smith's shoeing shed is called in Norfolk a Traverse. Edm. Heyward, of Little Walsingham, blacksmith, bequeaths to his wife, in 1517, “my place wich is called the house at the travesse,” a term which may probably have been connected with that occurring above. Norfolk Archæology, vol. i. p. 266. Palsgrave gives only “Trough for smythes, Auge à marichal.”

2 Antitodum, MS. and s. p. The composition of various kinds of Theriaca, an antidote for bites of serpents and venomous animals, is given by Pliny and other writers. Scribonius Largus speaks of it as made of the flesh of vipers. In the Middle Ages it was highly esteemed against poison, venom of serpents, and certain diseases; the nature of the nostrum may be learned from ancient medicinal treatises, such as Nic. de Hostresham's Antidotarium, Sloane MS. 341. The Treacle of Genoa appears to have been in very high repute; its virtues are thus extolled by Andrew Borde, physician to Henry VII. “Whan they do make theyr treacle a man wyll take and eate poysen and than he wyl swel redy to borst and to dye, and as sone as he hath takyn trakle he is hole agene.” Boke of the Introd. of Knowledge, 1542. Thus also says Caxton, in the Book for Travellers, “of bestes, venemous serpentes, lizarts, scorpions, flies, wormes, who of thise wormes shall be byten he must haue triacle, yf not that he shall deye!” We cannot marvel that costly appliances were often provided wherein to carry so precious an antidote, so as to be constantly at hand, such as the “pixis argenti ad tiriacam,” Close Roll 9 Joh.; the “Triacle box du pere apelle une Hakette, garniz d'or,” among the precious effects of Henry V.; the Godel, holding treacle, the gift of John de Kellawe, found with relics and offerings to the shrine of St. Cuthbert at Durham, in 1383; and the “Tracleere argenteum et deauratum cum costis de birall,” bequeathed by Henry, lord Scrope in 1415 to his sister. A curious illustration of the great esteem in which Treacle of Genoa was held, and of the difficulty of obtaining it unadulterated, occurs in the Paston Letters, vol. iv. p. 264; and in 1479, during the great sickness in England, John Paston entreats his brother Sir John to send him speedily “11 pottys of tryacle of Jenne, they shall coste xvj.d.—the pepyll dyeth sore in Norwiehe;” vol. v. pp. 260, 264. In Miles Coverdale's translation of Wermulierus’ Precious Pearle, it is said that “the Phisitian in making of his Triacle occupieth serpents and adders and such like poison, to driue out one poyson with another.” The term occasionally occurs to designate remedies differing greatly from the true theriaca. In Arund. MS. 42, f. 15 b. we read that juice of garlic “fordob venym and poyson myztily, and bat is be skyle why it is called Triacle of vppelond, or ellys homly foikys Triacle.”

501 1 Palsgrave gives “Pitfall for byrdes, Trebouchet.” The term which originally designated a warlike engine for slinging stones, and also, owing to a certain similarity in construction, the apparatus used in the punishment of the cucking stool (see p. 107, supra), signified also a trap or gin for birds and vermin. Ducange remarks, v. Trebuchetum,, Trepget, &c. “appellatio mansit apud Gallos instrumentis aut machinulis suspensis et lapsilibus ad captandas aviculas.”

501 2 See grece, or tredyl, supra, p. 209. In MSS. s. a. the reading is Tredyl of grace, which, if grece is taken here as signifying a staircase, may be more correct. See Nares, v. Grice.

501 3 Compare iogulowre, supra, p. 263. In the later Wicliffite version 2 Chron. c. 33, v. 6, is thus rendered, “Enchaunteris (ether tregetours) that disseyuen mennis wittis.” Chaucer uses the word, and also Treget, in allusion to marvellous tricks resembling those still practised in India. See Frankelein's Tale, and Tyrwhitt's note on line 11,453. Horman says, in his Vulyaria, “a iugler with his troget castis (vaframentis) deceueth mens syght; —the trogettars (præstiyiatores) behynd a clothe shew forth popettz that chatre, chyde, iuste and fyghte together.” Fr. Tresgier, magic, Tresgetteres, magicians, according to Roquefort.

501 4 Probably a knife for carving; such appliances were usually in pairs:—“Item, iij. paria de Trencheoura.” Invent, of Ric. de Ravensere, Archd. of Lincoln, 1385.

502 1 “A Trenket, ansorium, sardocopium,” cath. ang. “Trenket, an instrument for a cordwayner, Batton atourner soulies.” palsg. “Trenchet de cordouannier, a shoomaker's cutting knife.” cotg. In a Nominate by Nich. de Munshull, Harl. MS. 1002, under “pertinentia allutarii,” occur “Anserium, a sohavyng knyfe; Galla idem est, Trynket; —Pertinentia rustico.—Sarculum, a wede-hoke; Sarpa, idem est, Trynket.”

502 2 Compare trancyte, where menn walke, supra, p. 499. Horman says, in his Vulgaria, “I met hym in a Tresawne (deambulatorio) where one of the bothe must go backe.” A leaf of some early elementary book, found in the Lambeth Library, printed possibly by W. de Worde, contains part of a Nominale in hexameters. “Pergula (a galery), transcenna (a tresens), podium, cum coclea (a wyndyng steyr), gradus (a grece).” W. of Wyrcestre uses the term “le Tresance,” p. 288, signifying a passage leading to a hall, &c. Palsgrave gives only “Tresens that is drawen ouer an estates chambre, Ciel.”

502 3 Tryflom, M8. which seems doubtless an error, corrected by the other MSS. and by Pynson's printed text. See iapyn, supra, p, 257.

502 4 Possibly written trym, erroneously, as tryflom, supra.

502 5 Chaucer uses the word to Trill, to turn or twist, in the Squire's Tale, and speaks of tears trilling or rolling down the cheeks. In the translation of Vegecius, attributed to Trevisa, it is said of the “Somer castell or bastile,—thies toures must have crafty wheles made to trille hem lightly to the walles.” B. IV. c. 17. “I tryll a whirlygyg rounde aboute, Je pirouette. I tryll, Je jecte.” palsg. See trollynge, infra.

503 1 Possibly a trippet, which, according to Mr. Halliwell's Prov. Diet., is the same as trip, a ball of wood, &c. used in the game of trip, in the North of England, as described by Mr. Hunter in his Hallamshire Glossary. The ball is struck with a trip-stick. Tritura is rendered in the Ortus merely in its ordinary sense of threshing.

503 2 Scrutarius signifies a dealer in old clothes, or a bookbinder. See Ducange.

503 3 The repetition of this word here, in the Harl. MS. only, may be an error of transcript. Forby gives, as the pronunciation in Norfolk, Troant, pronounced as a monosyllable, a truant; and to Troant, play truant. “A trowane, discolus, trutannus. To be Trowane, trutannizare.” cath. ang.

504 1 Porticulus is explained in the Catholicon to be “baculus parvus ad portandum habilis, et porticulus vel portusculus malleolus in navi cum quo gubernator dat signum remigantibus in una vel in gemina percussione.” Palsgrave gives “Warder, a staffe.” Compare warder, infra.

504 2 “Lumbricus—vermis intestinorum et terre, quasi lubrieus, quia labitur, vel quia in lumbis sit.” cath. The following remedy is given “for tronchonys. Take salt, peper, and comyn, evynly, and make yt on powder, and zef it hym or here in hote water to drynke; or take the juse of rewe and zif it hym to drynke in leuke ale iij. tymes.” Manuale P. Leke, MS. xv. cent. Another occurs in a MS. version of Macer, under the virtues of Cerfoile. “Solue cerfoile with violet and vyneger, and this y-dronkyne wole sle wormis in the bely and the trenchis” (sic).

504 3 This word occurs between trumpon and trussyn, amongst the verbs, possibly as having been originally written truplytyn.

504 4 In provincial dialect, in some localities, Trussel signifies a stand for a cask. Mr. Wright, in his useful Dictionary of Obsolete English, states that the word signifies also a bundle, the diminutive doubtless of truss, and, in Norfolk, a trestle, a use of the term which Forby has overlooked. Moor gives, in his Suffolk Words, Tressels or Trussels, to bear up tables, scaffolds, &c, “Trussulla, a trussell.” ortus. This word also designated the punch used in coining. “Trousseau, a trussell, the upper yron or mould that's used in the stamping of coyne.” cotg.

504 5 Cumula, or cuuuila (?) MS. possibly for cuvvila. Compare covella, cuvellus, cupa minor. Due. French, cuve, cuveilette, a tub.

505 1 Compare tyte tust, supra, p. 494. Palsgrave gives “Tuske of heer, Monceau de cheueulx: Tufte of heer,” (the same). According to Mr. Halliwell's Archaic Glossary, Tuste has the same signification. See croppe, of an erbe or tree, supra, p. 104. “A twyste, frons; to twyste, defrondare; a twyster of trees, defrondator.” cath. ang.

505 2 Compare fy, supra, p. 159.

505 3 Cotgrave gives in French, “Tugure, a cottage, a shepheard's coat, shed or bullie.”

505 4 This verb is written likewise Twynkyn, in the Winchester MS. Horman says, in the Vulgaria, “Overmoche twyngynge of the yie betokethe vnstedfastnesse.—Twynlynge, connivens,” &c. Twink, in the dialect of some parts of England, is synonymous with Wink.

505 5 The tendrils of a vine are here intended. “Corimbi—dicuntur anuli vitis, queproxima queque ligant et comprehendunt.” cath.

505 6 Tuly appears to have been a deep red colour; the term occurs in Coer de Lion, “trappys of tuely sylke,” v. 1516, supposed however by Weber to be toile de soie. Gawayne, pp. 23, 33, &c. Among the gifts of Adam, abbot of Peterborough, 1321, a chasuble is mentioned “de tule samito.” Sparke, 232. See also in Sloane MS. 73, f. 214, a “Resseit for to make bokerham tuly, or tuly bred, secundum Cristiane de Prake et Beme;” the color being described as “a maner of reed colour as it were of croppe mader,” which by a little red vinegar was changed to a manner of redder color.

506 1 See the note on hove, or ground ivy, supra, p. 250. Skinner derives tun hove from A. S. tun, sepes, and hof, ungula, a hoof, from the form of the leaves; the name is, however, more probably as suggested by Parkinson, enumerating the various provincial appellations of the plant,—“Gill creep by the ground, Catsfoote, Haymaides, and Alehoof most generally, or Tunnehoofe, because the countrey people use it much in their ale.” Theater of Plants, ch. 93.

506 2 Compare fonel, or tonowre, supra, p. 170.

506 3 The mineral Turbith, a yellow sulphate of mercury, may be here intended. The word is found in the Winchester and Add. MSS. only. The term Turpethum, however, is explained by Rulandus in his Lexicon Alchemiæ, as derived from Arabic, and used to designate some bark or root of a plant, which may have been the spice with which the compiler of the Promptorium was familiar.

506 4 See flagge, supra, pp. 163, 164, and swarde, p. 482. “Turfe of the fenne, Tourbe de terre. Turfe flagge sworde, Tourbe.” palsg. “A Turfe, cespes, yleba. A Turfe grafte, turbarium,” cath. ang. The distinction above intended seems to be retained in East Anglian dialect, according to Forby, who gives the following explanation;—“Turf, s. peat; fuel dug from boggy ground. The dictionaries interpret the word as meaning only the surface of the ground pared off. These we call flags, and they are cut from dry heaths as well as from bogs. The substance of the soil belowthese is turf. Every scparate portion is a turf, and the plural is turves, which is used by Chaucer.” In Somerset likewise, peat cut into fuel is called turf, and turves, according to Jennings’ Glossary. In a collection of English and Latin sentences, late xv. cent. Arundel MS. 249, f. 18, compiled at Oxford for the use of schools, it is said,—“I wondre nat a litle how they that dwelle by the see syde lyvethe when ther comythe eny excellent colde, and namely in suche costys wher ther be no woodys; but, as I here, they make as great a fire of torves as we do of woode.”

507 1 “Turn seke, vertiginosus, vertigo est ilia infirmitas.” cath ang. “Twyrlsoght, vertigo.” Vocab. Roy, MS. De Infirmitatibus.

507 2 Treen is retained in E. Anglian dialect as an adjective, wooden. See Moor's Suffolk Words, v. Treen. Compare throwyn, and throwynge or turnynge of vesselle, supra, p. 493. It may be observed that before the manufacture and common use of earthenware, cups, mazers, and various turned vessels of wood were much employed, and the craft of the turner must have been in constant request. Chaucer, in the Reve's Tale, describing the skill of the Miller of Trumpington in various rural matters, says he could pipe, and fish, make nets, “and turnen cuppes, and wrastlen wel and shete.”

507 3 Compare tryllyn and trollyn, supra, pp. 502, 503.

507 4 Compare ovyr qwelmyn, supra., p. 374, and whelmyn, infra.

507 5 Gouldman gives “a tuttie, nosegay, posie, or tuzziemuzzie; Fasciculus.”

508 1 “Pedana, dicitur pedules novus vel de veteri panno factus quo calige veteres assuitur, Anglice a Wampay. Pedano, to Wampay. Pedula—pedules, pars caligarum que pedem capit, Wampaye.” ortus. “Vampey of a hose, Auantpied, Vauntpe of a hose, Vantpie.” palsg. “A vampett, pedana, impedia.” cath ang. See the Tale of the Knight and his Grehounde, Sevyn Sages, v. 843, where, having killed the dog which had saved his child from an adder, the knight is described as leaving his home demented; he sat down in grief, drew off his shoes,—“and karf his vaumpes fot-hot,” going forth barefoot into the wild forest. Here the term designates the feet of the hose or stockings; sometimes it significs a patch or mending of foot-coverings, as Vamp does at the present time.

508 2 Vaunton, as a-vaunton, MS.

508 3 Compare weryyn, or defendyn, infra. A. s. werian, munire.

508 4 In the Wicliffite version Prov. c. 23, v. 31 is thus rendered, “Biholde you not wyin whanne it sparclib, whanne be colour ber of schyneb in a ver.” In the Awntyrs of Arthure, 444, we read of potations served in silver vessels, “with vernage in verrys and cowppys sa clene.”

509 1 Vernage, Ital. vernaccia, is explained, Acad. della Crusca, to hare been an Italian white wine, as Skinner conjectures from Verona, qu. Veronaccia. See Ducange, v. Vernachia, and Garnachia; and Roquefort gives vin de Garnache. “Vernage and Crete” are mentioned as choice wines, Sir Degrevant, lin. 1408; in “Colin Blowbolle's Testament,” notes to Thornton Romances, edited for Camd. Soc. by Mr. Halliwell, p. 301, we find in an ample catalogue of wines—“Vernuge, Crete, and Raspays.” In the Forme of Cury, directions occur to “make a syryp of wyne Greke, ether vernage.” “Regi theriacum in vino vocato le Vernage dederunt.” Ang. Sac. t. ii. p. 371.

509 2 See directions for making “Vernysche,” about the period when the Promptorium was compiled, Sloane MSS. 73, f. 125, b. 3548, f. 102. “Bernyx, or Vernyx, is a bynge y mad of oyle and lynne sed, and classe, with (which) peyntours colours arn mad to byndyn and to shynyn.” Ar. MS. 42, f. 45, b. The Latin word above may be more correctly read Vernico.

509 3 Hardyng relates that St Ebbe and the nuns in her company cut off their noses and upper lips, (which was “an hogly sight”) for fear of the Danes—“to make their fooes to hoge (al. houge or vgge) sowith the sight.” Chron. c. 107. “Uglysome, horryble, execrable.” palsg. “To Hug, abhominari, detestari, rigere, execrari, fastidere, horrere. Hugsome, abhominacio, &c. To Vg, abhominari, &c. ut in H. litera. Vgsome, Vgsomnes,” &C. cath ang.

509 4 “Vyce, a tournyng stayre, Vis. Vyce of a cuppe, Vis. Vyce to putte in a vessel of wyne to drawe the wyne out at, Chantepleure.” palsg. Chaucer describes how suddenly waking in the still night, he paced to and fro, “till I a winding staire found—and held the vice aye in my hond,” softly creeping upwards. (Chaucer's Dream). Here Vice seems to designate the newel, or central shaft of the spiral stair. In the Contract for building Fotheringhay church, 1435, is this clause,—“In the sayd stepyll shall be a Vyee tournyng, serving till the said body, aisles, and qwere both beneth and abof;” the “vyce dore” of the steeple is mentioned in Churchwardens’ accounts at Walden, Essex; and amongst payments for building Little Saxham Hall, 1506, occur disbursements for a vice of freestone, and another of brick, which last is called in the context a “staier.” Gage's Suffolk, pp. 141, 142. In the earlier Wicliffite Version, Ezek. 41, v. 7, is thus rendered—“and a street was in round, and stiede upward bi a vice (cochleam), and bar in to be soler of be temple by cumpas; (styinge vpward by the heez toure” later version.) “A vyce, ubi a turne grece.” cath ang. Roquefort gives “Viz.; escalier tournant en forme de vis.”

510 1 Some kind of brooch, a fastening for the hood, seems to be here intended. The capitium, or chevesaille, was closed at the neck with some such ornament, to which, from certain peculiarities in its fashion, the name spira may have been properly assigned. Chaucer describes, Rom. of the R. v. 1080, that with a tasseled gold band and enameled knops “was shet the riche chevesaile” worn by Richesse.

510 2 Vinarium, according to Ducange, may signify a vineyard, or a wine-vessel, poculum. The term which occurs above may, however, designate a vessel for vinegar, Vinaigrier, Fr. The cruets for wine, or buretles, for the altar, are sometimes called vinageritæ, or vinacheriæ.

510 3 This term may probably be traced to the French Vironner, to veere, turne about; Virer, to wheel about, &c. cotg. From the rotatory movement doubtless certain mediæval machines were called Vernes, or Fearnes, as in accounts of works at Westminster Palace, t.Edw. I., where, with payments for ropes, &c. mention frequently occurs of “gynes voc' femes;” and, in the Compotus of W. de Kellesey, clerk of the works, 1328, many payments occur for timber and iron-work, “circa facturam cujusdam Verne sive Ingenii constructi pro meremio majoris pontis aquatici Westmonasterii rupti decaso et jacente in aqua Tamisie ibidem exinde levando et guyndando.” Misc. Records of the Queen's Remembrancer, 2 Edw. lit. “Moulinet à brassiéres, the barrell of a windlesse or fearne. Chevre, the engine called by architects, &c. a Fearne.” cotg.

510 4 The ring of metal now termed a ferrule. The Duchess of Brabant gave to her father Edw. I., as a new year's gift, “j. par cultellorum magnorum de ibano et eburn' cum viroll' arg' deaur.” Lib. Gard. 34 Edw. I. In the St. Alban's Book, sign. h. j. are directions for making a fishing-rod;—“Vyrell the staffe at bothe endes with longe hopis of yren or laten in the clennest wyse, with a pyke in the nether ende, fastnyd wytb a rennynge vyce to take in and oute youre croppe” (i. e. the top joint).

511 1 Undern, the third hour of the day, Ang.-S. Undern, occurs in Chaucer, Sir Launfal, Liber Festivalis, &c. Sir John Maundevile says that in Ethiopia, and other hot countries, “the folk Iyggen alle naked in ryveres and wateres from undurue of the day tille it be passed the noon (a diei hora tertia usque ad nonam).”

511 2 Vnderfettyn, MS. as also the verb following. Doubtless errors of the copyist.

511 3 Chaucer mentions “undermeles and morweninges,” Wife of Bathes T. See Nares, Coles, &c. “An orendron, meridies; An orendrone mete, merenda; To ete orendrone mete, merendinare.” cath ang. “Gouber, an aunders meat, or afternoones repast.” cotg.

512 1 Sic MS. “Vook; vox” in MS. H. and P. after “Voys; vox;” it is not found in MS. K. Possibly an error by the second hand. volatyle, wyld fowle, altile, occurs immediately after, in the other MSS. “Mi bolis and my volatilis ben slayn.” Matt. c. xxii. v. 4. Wicl. Vers. Piers of Fulham complains of the luxury of his day, when few could put up with brawn, bacon, and powdered beef, but must fare on “volatile, venyson, and heronsewes.” Hartshorne, Met. Tales, p. 125. See also Ooer de Lion, v. 4225.

512 2 “Vpholstar, frippier.” palsg. Caxton, in the Booke for Travellers, gives “Vpholdsters—vieswariers.—Euerard the vpholster can well stoppe (estoupper) a mantel hooled, full agayn, carde agayn, skowre agayn a goune and alle old cloth.”

512 3 See, in Stat. 37 Edw. III. c. 3, de victu et vestitu, regulations regarding the price of poultry, that of a young capon not to be above 3 den., an old capon 4 den. “et que es villes a marchees de Vpland soient venduz à. meindre pris,” as agreed between buyer and seller. “Rude, rustycal, or vplondyssche, rusticus.” Whitinton Synon. “Vplandyssheman, paysant; vplandyssheness, ruralite.” palsg. Horman says—“Vplandysshe men (agricoli) lyue more at hartis eese than som of us. The monk stole away in an vplandisshe mans wede (villatico indutus panno). In as moche as marchaundis is nat lucky with me, I shall go dwell in Vplande (rus concedam).” See Riley's Gloss. Liber Albus, v. Uplaund.

512 4 “An Vrchone, ericius, erinacius.” cath.ang. “Urchone, herisson. Irchen, a lytell beest full of priekes, herison.” palsg. In Italian, “Riccio, an vrchin or hedgehog.” florio. Horman says that “Yrchyns or hedgehoggis be full of sharpe pryckillys; Porpyns haue longer prykels than yrchyns.” According to Sir John Maundevile, in the Isles of Prester John's dominions “there ben Urchounes als grete as wylde swyn; wee clepen hem poriz de Spyne;” p. 352

513 1 See also welde, or wolde, infra, Sondix, which is rendered in the Ortus, “madyr or wode.” Palsgrave gives “Wode to die with, Guedde.” A. Sax. Wad, glastum.

513 2 Compare Fr. “Guementer.gemir; Weimentauntz,éploré.” roqef. See Sir P. Madden's Glossary, Syr Gawayn. “I wement, I make mone, Je me guermente; It dyd my hert yll to here the poore boye wement whan his mother was gone. Weymentyng, Granite.” palsg. “Lamentor, to wayment.” med.

513 3 — or a.garloment, MS. and likewise in MS. S. The reading in Pynson's printed text appears preferable. Compare garmente, supra, p. 187. “Lacinia, ora sive extremitas vestimenti,” &c. cath. Compare trayle, or trayne, supra, p. 499. “Lacinia, a hemme, ora vestis.” ortus. Fr. guenelle; banderolle.

513 4 “Wayre, where water is holde, Gort.” palsg. In Suffolk, Waver, a pond. Lat. Vivarium.

513 5 Compare spy, or watare, supra, p. 469.

513 6 See also kenytn, or priuely waytyn, supra, p. 269.

page 514 note 1 Compare Reysyn Vp fro slepe, supra, p. 428.

page 514 note 2 Probably for scorynge. Compare Scowryn wythe a baleys, supra, p. 450; and Strype, or schorynge wythe a baleys, p. 480. The reading of MS. s. is stonyng (? an error by the copyist for scoryng.) “Wall of a strype, Enfleure.” Palsg.

page 514 note 3 “Nausea, evomere, et proprie in navi ad vomitum provocari, et voluntatem vomendi habere sine affectu; to wamble.” Ortos. “Allecter, to wamble asaqueasie stomacke dothe.” Cotg. In Trevisa's version of Barth. de Propriet. it is said of mint,— it abateth with vynegree parbrakinge, and oastinge, that comethe of febelnesse of the vertue retentyf; it taketh away abhominacion of wamblyng and abatethe the yexeing.”

page 514 note 4 To Wallop, according to Forby, signifies in Norfolk to move fast with effort and agitation, as the gallop of a cow or carthorse. Compare Jamieson. “But Blanchardyn with a glad cbere waloped his courser as bruyantly as as he coude thurghe the thykkest of all the folke, lepyng here and there as hors and man had fowghten in the thajer.” Blanchardyn and Eglantyne, Caxton, 1485. Cotgrave gives the phrase “Bouiller une onde, to boyle a while or but for one bubble, or a wallop or two.”

page 514 note 5 Compare Welwynge, infra. “Walterynge as a shyppe dothe at the anker, or one yttourneth from syde to syde, En voultrant.” Palsg. adverbially. See Forby, v. Walter, or Wolter, to roll and twist about on the ground, as corn laid by the wind, &c. or as one rolled in the mire.

page 515 note 1 Compare Med. Gr. Hart. MS. 2257,— Despero, a spe cessare, to wanhope.” Palsgrave gives— “Wanhope, desespoir.” Horman says in the Vulgaria,— “Thou shalt put them out of wanhope,” (error); and, in the version of Vegetius (Roy. MS. 18A. XII.) amongst sleights of war, it is said— “They þt besege cities they w'drawe hem a-wey fro the sege as thoughe they were in despeire or wanhope of þe wynnyng.” The word occurs likewises Sir J. Maundevile, p. 346, and in Piers PI. passim.

page 515 note 2 Compare Wax Wantōn, infra, where the reading of MS. K. is wantowe.

page 515 note 3 A marginal note in the copy of Pynson's edition in Mus. Brit, here supplies—wrapping. Compare Wyndyn' yn clothys, idem quod, wrappon, infra; and also Lappyn, or whappyn yn cloþys, supra, p. 287. Forby gives to “Hap, to cover or wrap up.—Wap, to wrap. Sui-Cr. wipa, involvere.” Vocab. of E. Angl. In Arund. MS. 42, f. 8b. it is said that “for þe frenesy is a myjty medycyn—yf þu take a whelpe and splat hym as ho openeþ a swyn—and al hot wap þe hed þeryn;” and, f. 41, a poultice of houseleek and flour “wapped and hiled wel with grene levys,” is given as a remedy for gout.

page 515 note 4 Compare Porby, v. Wappet, a yelping cur; and Yap. Dr. Caius gives “Wappe,” in the same sense. De Canibus Brit.