Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

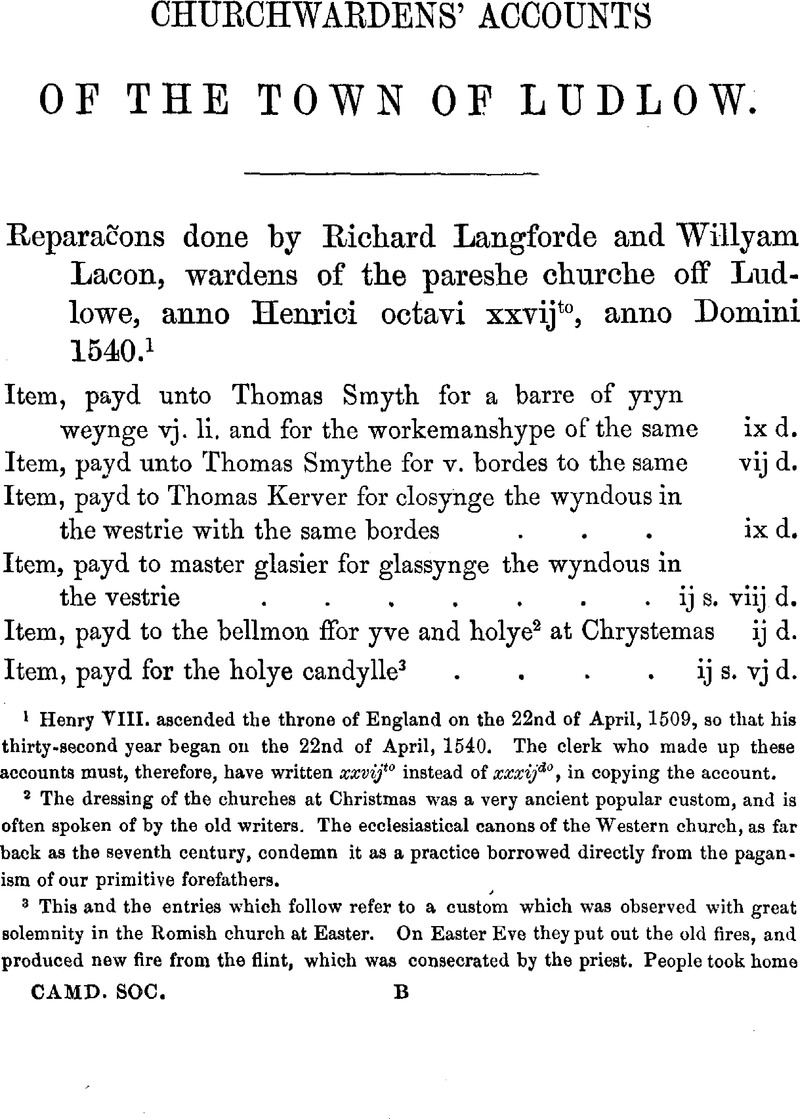

page 1 note 1 Henry VIII, ascended the throne of England on the 22nd of April, 1509, so that his thirty-second year began on the 22nd of April, 1540. The clerk who made up these accounts must, therefore, have written xxvij to instead of xxxij do, in copying the account.

page 1 note 2 The dressing of the churches at Christmas was a very ancient popular custom, and is often spoken of by the old writers. The ecclesiastical canons of the Western church, as far back as the seventh century, condemn it as a practice borrowed directly from the paganism of our primitive forefathers.

page 1 note 3 This and the entries which follow refer to a custom which was observed with great solemnity in the Romish church at Easter. On Easter Eve they put out the old fires, and produced new fire from the flint, which was consecrated by the priest. People took home lights of this fire to renew the fires in their own houses, as carrying with it a sort of blessing to their homes (it was another relic of paganism). But chiefly they lighted from it an immense candle of wax, or taper, which was called the Paschal candle, and was consecrated with very great solemnity. This is told in the old Latin verses of Hospinian:

Cereus hinc ingens, Paschalis dictus, amœno

Sacratur cantu; cui ne mysteria desint,

Thurea compingunt in facta foramina grana.

This was kept burning until Easter Day, when it was extinguished in the holy water, which was then renewed for the forthcoming year. The taper was generally very large, as will be seen by the entries in our churchwardens' accounts. In 1557, the Paschal taper for the abbey church of Westminster weighed three hundred pounds.

page 2 note 1 i. e. altar.

page 2 note 2 Crule, spelt in later times crewel, was a fine worsted thread, which was used of course for sewing on the rings,

page 3 note 1 The valance was the drapery raised over the high altar at the solemnity of Easter.

page 3 note 2 There is in the MS. the mark over the e usually signifying the n to follow e; but, as this is sometimes used with no meaning in this Manuscript, I dare not resolve decidedly whether the word should be egle or engle.

page 3 note 3 In the first of these examples the word is clearly written crofer, but probably the second is correct, cofer, in the sense of a chest.

page 3 note 4 A bar.

page 3 note 5 Pins.

page 3 note 6 ? Wire.

page 3 note 7 A coarse kind of tape.

page 4 note 1 The organ-soler was the floor on which the organ was raised.

page 4 note 2 ? Winding-door.

page 4 note 3 This was a part of the mechanism of the bell, often mentioned in old churchwardens' accounts, the exact character of which is at present rather uncertain. Baldric, or baudric, means a belt or girdle, and it is said to have been given to a belt or thong by which the clapper of the bell was suspended.

page 4 note 4 Pit seems to have meant a graves.

page 4 note 5 The bier on which the dead were carried to their graves.

page 4 note 6 To parget or rough-cast a wall.

page 4 note 7 Fathoms.

page 4 note 8 Mass bell.

page 4 note 9 The chimes.

page 4 note 10 Liquor.

page 5 note 1 Coals, i. e. charcoal.

page 5 note 2 All Saints.

page 5 note 3 It was the custom to construct a sepulchre, of course representing that of the Saviour, with various ceremonies ; on Good Friday, the hoste was placed in it, and men were paid to watch it night and day until Easter day, in the morning of which the hoste was taken out, and it was announced that Christ had arisen.

page 5 note 4 The singing-bread was the consecrated wafers.

page 5 note 5 Fat, in old records, means usually a vat, or vessel ; but it here signifies something which was bought by the pound, probably fat for the links or torches.

page 5 note 6 The meaning of the word leystalle or laystalls in connection with a church is not very clear; but it appears to have had some relation to a pew. One meaning attached to the word is a place for cattle to rest in after a long journey.

page 6 note 1 The contraction is rather indistinct here, and the v apparently an error, for it is probably intended for sterling.

page 7 note 1 Probably it should be poryche, the porch.

page 7 note 2 Solder.

page 7 note 3 In a former passage, p. 4, the word is spelt distinctly wendinge.

page 7 note 4 The paschal table.

page 7 note 5 Piecing one of the pillars.

page 7 note 6 For white tape for the albes.

page 8 note 1 Perhaps for alias.

page 8 note 2 Piecing.

page 8 note 3 Solder.

page 9 note 1 Elder-trees.

page 9 note 2 Washing and sewing the albs.

page 10 note 1 Notes?

page 10 note 2 Catherine's.

page 10 note 3 The Promptorium Parvulorum has “WECCHE, of a clokke,” but gives no further explanation.

page 10 note 4 His two men for hanging.

page 10 note 5 The iron chair in the high choir.

page 10 note 6 Rubbish thrown out of the grating.

page 11 note 1 Weight ?

page 11 note 2 Three loads, or bundles, of rods to mend the lodge?

page 11 note 3 A measure of lime, but how much I cannot ascertain.

page 11 note 4 . To whitewash the walls.

page 11 note 5 On which to suspend the bells.

page 11 note 6 Easter Eve.

page 11 note 7 I do not know this word.

page 12 note 1 steeple.

page 12 note 2 lodge.

page 12 note 3 These links, or torches, were probably intended for lighting at the paschal fire.

page 13 note 1 The noble above spent. A noble was 6s. 8d.

page 13 note 2 latches.

page 14 note 1 “Sir William” was of course the priest of St. Leonard's, a little chapel on the northern side of Corve Street, Ludlow, the ruins of which were visible at no very remote period. Sir, the English representative of dominus, was the usual title of a priest. How it happened to the priest of St. Leonard's to sell a “Pistille Boke,” or book of the Epistles, to the church of Ludlow, is not very clear. Perhaps he had employed his leisure in writing it, and sold the MS. to the churchwardens.

page 14 note 2 Thread.

page 14 note 3 Ivy. The decking of churches and houses at Christmas with ivy and holly is a custom of great antiquity, and is spoken against with strong disapproval by the earlier ecclesiastics, as being derived from the pagans.

page 14 note 4 The jury, of course, in the course of a law-suit here alluded to. A penny a man for treating them seems moderate, according to our present notions.

page 15 note 1 The dogs appear, in those days, to have been kept under little restraint, and to have been very troublesome. From this necessity of driving them out of the church arose the title of dog-whipper, which is still given in some parts of England to the church-beadle. In the sixteenth century a similar title was given to the monk who had charge of the church in some of the continental monasteries.

page 15 note 2 Dowlas, a sort of coarse linen brought from Britany.

page 16 note 1 surplice.

page 16 note 2 i. e. for iron-old iron from the church repairs.

page 16 note 3 decease.

page 16 note 4 The sum is not entered.

page 17 note 1 Grate, or trellis. The Promptorium Parvulorum has, “GRATE, or trelys wyndowe, Cancellus.” The cross-bars of the window were usually of wood.

page 18 note 1 Cupboard.

page 18 note 2 It would appear that, when the glazier came to work, a table (board) was made for him at the expense of the churchwardens.

page 19 note 1 Resin.

page 20 note 1 I have not been able to trace any property in Galford belonging to the church bearing, as we might expect, such a name as Shermon's Close; but it is very singular that there is a court in Galford, on the left-hand side going towards Cainham, which is called Charmer's Court, but which is understood to have derived its name from an old man named, or nicknamed, Dickey Charmer, who went about the town selling fish, &c. and was well known some years ago, and who lived in this court. May not the two names have been confounded, and the name of the Charmer of modern Ludlow have replaced the Shermon of these Churchwarden's Accounts ? It is a sort of transformation which is met with not uncommonly in our old towns.

page 21 note 1 Ridding, clearing.

page 21 note 2 A wheel.

page 22 note 1 A citation, or summons.

page 23 note 1 The Deacon's chamber.

page 23 note 2 A seam or horse-load of wood.

page 24 note 1 The writer has apparently omitted the name of this servant's master.

page 24 note 2 A wheel.

page 24 note 3 The parish bier.

page 24 note 4 I cannot explain satisfactorily this word.

page 24 note 5 For a citation.

page 25 note 1 The cable.

page 25 note 2 cans.

page 25 note 3 The hammers were for the chimes.

page 26 note 1 The dirge celebrated on the death of King Henry VIII. The King died on the morning of Friday, January 28th, 1547.

page 26 note 2 Tape. See before, p. 7.

page 26 note 3 amice.

page 26 note 4 piecing.

page 26 note 5 fetch.

page 28 note 1 The book of the moneys gathered from the commonalty of the town.

page 28 note 2 dozen.

page 28 note 3 absence.

page 29 note 1 Curfew.

page 29 note 2 Ivy.

page 29 note 3 Iron clamps for fastening boards together.

page 30 note 1 The reading of this word is rather doubtful; perhaps it should be alleluias.

page 30 note 2 The word to shot or to shut, is frequently applied to the bell ropes in the course of these accounts. It perhaps means to piece or mend them when broken. The word is sometimes used in the sense of to strengthen.

page 30 note 3 yards?

page 30 note 4 Wheel. This orthography is rather curious, as it would seem to show that the i was often pronounced as e. It is supposed that in Anglo-Saxon the vowels were pronounced as they are now in German and French, and in most of the continental languages, and that this continued to be the case in Old English down to a rather late date. The period of transition may have been as late as the beginning of the sixteenth century.

page 32 note 1 See before, the note on p. 20. The land appears to have been given to the church with a condition that it should not be ploughed the first year.

page 33 note 1 I suppose, splicing the rope.

page 33 note 2 Wheel.

page 33 note 3 If this means painting, it is rather curious that so much money should have been spent on painting the rood-loft just at this period, when the church was on the eve of being defaced by the removal of so much of its Romish furniture, as we see in the very next entry.

page 34 note 1 Load.

page 34 note 2 Singing-bread was the name for the consecrated wafers, of which we here see that half a thousand cost twopence halfpenny.

page 34 note 3 Coals-no doubt, charcoal.

page 35 note 1 Perhaps, for binding.

page 35 note 2 Wheel.

page 35 note 3 Six rings of lime, to parget or rough-cast the leads. The word ring, as a measure of quantity, appears to be entirely obsolete.

page 35 note 4 The king's “visitors, who were sent here to examine the amount of superstitious usages existing in the church, and into the claims of the guild.

page 35 note 5 Painting.

page 35 note 6 This appears also to be another popular name for a measure the exact meaning of which is now lost.

page 35 note 7 i. e. defacing the superstitious figures which adorned it.

page 36 note 1 It would hardly be possible at present to identify the exact site of the different chancels and chapels in our church mentioned in these entries. My friend Mr. R. Kyrke Penson, who is better acquainted with the history of the fabric of Ludlow church than anybody else I know, and whom I have consulted on this subject, informs me that “the only point about which there appears to be any certainty is that the Lady Chapel was on the south of the church. No one has been able to make out where St. George stood. There were chapels at intervals, as is evident from the existing piscinas, down the north and south aisles, and possibly St. George and St. Margaret may have stood in them. Beawpy's chapel is a puzzle, becauee the two church aisles which might be called-chapels are known to be St. John's and the Lady Chapel.”

page 37 note 1 Churchyard the poet, in his Worthines of Wales, says that Beawpy was buried near the Font, and gives the following account of him :—

“Yet Beawpy must be nam'd, good reason why,

For he bestow'd great charge before he dyde

To helpe poore men, and now his bones doth lye

Full nere the font, upon the foremost side.”

page 39 note 1 Load. See before, p. 34.

page 39 note 2 White-liming, or whitewashing, the church walls.

page 40 note 1 It is not quite clear in the MS. whether the first letter of this word be b or l, but it seems to be the former.

page 42 note 1 This was no doubt the beam the expenses of carving which are accounted for on a former occasion. See p. 11.

page 42 note 2 No doubt the old timber house still standing there, nearly facing the eastern end of the church. The two burthens of rods were probably the laths or boards used in the walls. This is the date to which we may perhaps trace the present building.

page 42 note 3 It seems to mean plaistering, or something of that kind ; see a few lines further on, where it occurs again.

page 43 note 1 i.e. to protect.

page 43 note 2 Bell-wheels.

page 43 note 3 See this word explained in the note on p. 4.

page 44 note 1 I am not aware that there are any remains of this window at present. The figure of St. Margaret was probably represented in the stained glass.

page 44 note 2 I presume a whirle-gate was what we call a turnstile. It probably led into the churchyard opposite {anont) the buildings of the College.

page 45 note 1 For half a hundred lacking four pounds.

page 46 note 1 Rubbish.

page 47 note 1 Deacons.

page 47 note 2 To cover the floor.

page 51 note 1 This is a word with which I am unacquainted, but perhaps it is a corruption of boss.

page 53 note 1 Surplice.

page 53 note 2 week.

page 54 note 1 The blank is left in the original.

page 56 note 1 I have not met with this word in any sense which could be accepted here. Tonnycle is given in the Promptorium Parvulorum as the English name for one of the ecclesiastical vestments. Perhaps it is here merely the diminutive of tonne, or tunne, explained in the Promptorium by the Latin dolium.

page 56 note 2 The word here appears evidently to mean making a pentice.

page 56 note 3 Coals.

page 58 note 1 The exact spelling of this word is a little doubtful in the manuscript.

page 58 note 2 This must be Richard Sampson Bishop of Lichfield, who had held the high office of Lord President of Wales and the Marches from 1543 to 1548, when on the accession of Edward VI. he was removed, but he was perhaps temporarily restored on the accession of Mary.

page 58 note 3 Another hand has written over the line “Ph',” i.e. Philippus. The marriage of Queen Mary with Philip of Spain took place on the 25th of July, 1554, with which day, which was now called the first day “of the first and second year of the reign of Philip and Mary,” began the new regnal year, which will be found at the head of the present churchwardens' year.

page 60 note 1 i. e. frankincense.

page 60 note 2 curfew.

page 60 note 3 In the dialects of the West of England a fireshovel is still called a slice.

page 61 note 1 Dowlas, a sort of coarse linen imported from Britany.

page 61 note 2 Perhaps the ceremonial dress of the weavers, mended now for some special occasion.

page 61 note 3 cheker lace.

page 61 note 4 i. e. Gild.

page 62 note 1 The gudgeon was the large pivot of the axis of a wheel.

page 62 note 2 The canopy.

page 62 note 3 I am unacquainted with this term, which is probably a local word for a certain quantity.

page 62 note 4 Fixing on.

page 62 note 5 Perhaps for appareling.

page 62 note 6 The Austin Friars, in Goalford, the ruins of which monastic house had at this time already become a great source of building and other materials.

page 63 note 1 Muck.

page 63 note 2 Sixes, as it is written in another place.

page 63 note 3 i. e. ivy.

page 64 note 1 A fair was perhaps held on the day of St. Lawrence, the patron of the Church, the dues, &c. of which went to the Church.

page 65 note 1 ? fixing.

page 66 note 2 The vessel in which the frankincense was kept, and which in the medieval Church was made in the form of a ship. Ducange, under the word Navis, quotes the will of a bishop of Beauvais, dated in 1217, who left to his cathedral, among other things, “calicem unum aureum, et navem argenteam, et missale.”

page 66 note 1 These last three words are added in a different hand.

page 66 note 2 This “brick close” is not unfrequently mentioned in the course of these Accounts, but its exact position is not described.

page 66 note 3 end.

page 67 note 1 The gudgeon was the large pivot of the axle of a wheel.

page 67 note 2 A hook.

page 68 note 1 pulleys.

page 68 note 2 binding, which appears to have been expensive at this time ; or this book must have been very richly bound.

page 68 note 3 Probably some local name for a measure of charcoals.

page 68 note 4 Dowlas, see before, p. 15.

page 69 note 1 This is I think the first of these Accounts in which the word charcoals is used, and it would seem to show that the use of mineral coals was becoming more common. Charcoal is found as the interpretation of carbo in the Promptorium Parvulorum, the English-Latin dictionary of the middle of the fifteenth century.

page 70 note 1 laths.

page 71 note 1 Bellows.

page 71 note 3 These were of course two of the important books of the Popish service, the Processional and the Antiphonary.

page 73 note 1 Hair-cloth.

page 73 note 2 Dornik, or Doornick, is the Flemish name for the town which the French and English call Tournay, where formerly a flourishing trade was carried on in linen manufactured there. The alb here mentioned was no doubt made of Tournay linen. At this time, for several reasons, an extensive trade was carried on between our country and Flanders.

page 74 note 1 It may be perhaps well to remark that ser, or sir representing the Latin dominus, was the usual title of a priest, or of any one who had taken his first university degree.

page 76 note 1 Charcoals.

page 76 note 2 Board-nails.

page 76 note 3 Forty fathoms. It appears that ropes of great magnitude were fetched from Worcester.

page 77 note 1 The gudgeon. See before, p. 67.

page 79 note 1 Laths. They were used apparently for repairing or enlarging the timber house in the churchyard, which appears to have been done to a considerable extent in this year.

page 79 note 2 Another form of baldrick.

page 80 note 1 A word I have not met with elsewhere, nor do I know its meaning.

page 80 note 2 The saints' bell, or small bell which called to religious services.

page 80 note 3 Also a word I have not previously met with.

page 81 note 1 This means apparently to cover or strengthen the second floor, but I have not met with the word elsewhere.

page 81 note 2 All Saints' day.

page 81 note 3 An angel was a gold coin of the value of 6s. 8d. (which became a lawyer's fee), but an old angel appears at this time to have been of considerably more value.

page 82 note 1 Communicants. To housele, in old English, meant, to administer the sacrament. The word in Anglo-Saxon was huslian, to make the offering, and husel, or husol, meant the offering of the sacrament.

page 84 note 1 This item is cancelled in the original.

page 84 note 2 I suppose that the word hands means here, handles ; and that clystes were some materials used for making them. In old French the word clister meant, to cover with rags.

page 84 note 3 Wheels.

page 85 note 1 Pieces of iron.

page 85 note 2 Apparently the, perhaps local, name of some measure of quantity.

page 85 note 3 The hither side, or side towards the town.

page 86 note 1 The rood.

page 86 note 2 Of course, this means Dinham. It is curious that the very early form of the name should have been preserved to so late a date.

page 86 note 3 i. e. The Antiphonary.

page 86 note 4 A staple.

page 86 note 5 The rood.

page 87 note 1 A pail for lading, still called in Northamptonshire a lude-pail.

page 89 note 1 I have not met with this word elsewhere.

page 89 note 2 Thread.

page 89 note 3 Ivy leaves.

page 90 note 1 A whope of charcoles occurs on a former occasion. See p. 68.

page 90 note 2 In the dialect of Gloucestershire, they still say to liquor, for to oil.

page 90 note 3 To piece.

page 90 note 4 This sort of candle has not been mentioned before.

page 90 note 5 The pall.

page 91 note 1 Lath nails ; I have not met with houle nails before.

page 91 note 2 To pin clouts, or cloths.

page 91 note 3 Black Monday was a popular name given to Easter Monday, in memory, it is said, of the severity of the weather on that day (April 14, 1360), when King Edward the Third's army, then before Paris, suffered greatly from it.

page 92 note 1 Key.

page 93 note 1 i.e. for writing musical notes.

page 93 note 2 Rood. The Protestant feelings of Elizabeth's reign are now beginning to show themselves.

page 94 note 1 I cannot explain this word, which is clearly the reading of the manuscript.

page 94 note 2 Begging-box, or alms-box.

page 94 note 3 Altars.

page 94 note 4 Brazing. We have before had payments for brassynge a candlestick.

page 95 note 1 Aisle.

page 95 note 2 Rushes to strew.

page 96 note 1 The altar.

page 96 note 2 A rail.

page 97 note 1 The wedding door has been frequently mentioned in these accounts. Before the Reformation, important parts of the Services of baptism, matrimony, and the churching of women, were performed at the church door, usually in the porch. The reader of Chaucer will remember what he says (Cant. T. I. 462) of the Wife of Bath,—

“Housbondes atte chirche dore hadde sche fyfe.”

It is for this reason, no doubt, that we find holy-water stoups so commonly in old porches of churches. It was directed in the will of Henry VI. that there should be “in the south side of the body of the church of Eton College a fair large dore with a porche, and the same for christeninges of children and weddinges.” At the southern entrance of Norwich Cathedral, there is a representation of the Sacrament of marriage carved in stone. The custom was that the parties did not enter the church till that part of the office when the minister now goes up to the altar and repeats the Psalm. Part of the ceremony under the porch consisted also in the endowing of the bride, which was called doa ad ostium ecclesiœ. The door at which the wedding was performed appears to have been generally on the southern side of the church, but at Ludlow it was evidently not the porch, and, from an entry a few lines further on, it would appear to have been on the north side.

page 98 note 1 So in the MS., but no doubt a mere error of the scribe for wedinge.

page 98 note 2 Aisle.

page 100 note 1 For Goalford, no doubt.

page 101 note 1 Guild.

page 101 note 2 Panes of glass.

page 102 note 1 Allusions to this custom have occurred before. Seep. 15. It may be remarked that this office was not confined to England, and it appears to have been of some antiquity. It is mentioned in the “Contesd'Eutrapel,” by the well known French satirical writer of the sixteenth century, Noel du Fail, who, in one of his facetious stories, the scene of which lay in a monastery, says, “survient un quidam enfroqué, ayant la charge d'éteindre les chandelles et chasser les chiens kors d'église.” (Contes d'Eutrapel, Conte xx.) The dog-whipper here was a monk, eufrogué.

page 102 note 2 Given.

page 103 note 1 Sweeping.

page 104 note 1 ‘This was no doubt Sir Henry Sydney, newly appointed to the high office of Lord Prosident of Wales and the Marches.

page 104 note 2 Apparently for. parvis. The parvis was the open place before the porch or entrance to a church, and it may here mean the place before the clock.

page 104 note 3 A joist ?

page 104 note 4 I do not know this word.

page 104 note 5 The belfry.

page 104 note 6 The sollar, or upper room.

page 105 note 1 Weight.

page 106 note 1 Even, or Evo.

page 108 note 1 Holly and ivy.

page 108 note 2 Candlemas eve.

page 108 note 3 Callends, or callens, or, as it is called in another place, skallends, was the name given here and in one or two other localities, to the liche-gate, or entrance through which a corpse was carried into the church-yard, and where it rested. The passage by which the porch of the church of Ludlow is approached from the town still bears the name, and no doubt occupies its site.

page 109 note 1 Stirrups, perhaps here, steps for mounting.

page 109 note 2 Wire.

page 109 note 3 The apparitor.

page 109 note 4 A measure which has been frequently mentioned before.

page 110 note 1 I have not met with this word, or thele, before.

page 112 note 1 The use.

page 112 note 2 According to the list of bailiffs printed in my History of Ludlow, p. 493, William Poughnill and Richard Starr were elected bailiffs in 1561. The latter name is no doubt an error of the copyist for Farr.

page 113 note 1 The bailiffs this year were, according to the list quoted in a former note, Robert Mason and John Holland. The name of Draper does not appear in the list as a bailiff.

page 114 note 1 The jack.

page 114 note 2 So it is written abbreviated in the manuscript.

page 115 note 1 This word appears to mean a cushion, or stool.

page 118 note 1 In the MS. it is clearly rasters, but the long s and the f are so nearly alike, that we cannot always distinguish them, and it may be intended for rafters.

page 119 note 1 Probably a local word.

page 119 note 2 Another word the meaning of which is obscure.

page 120 note 1 After this, there are six pages of the manuscript left blank, no doubt to receive the Churchwardens' accounts for 1565, which were never entered.

page 122 note 1 The Turks were at this time threatening Europe in the East and in the Mediterranean, and prayers were ordered to be offered up against them in parish churches all over England. In the Church Wardens' Accounts of the parish of St. Helen's, Abingdon, the following entry occurs: “Anno 1565, payde for two bookes of common prayer agaynste invading of the Turke, vj d.” Sixpence appears to have been the established price of this book of prayer.

page 125 note 1 A name for a measure or quantity which I have not met with elsewhere.

page 125 note 2 Roof.

page 125 note 3 Irons.

page 125 note 4 To view, examine.

page 125 note 5 Fetching.

page 125 note 6 Perhaps we should read Passe (i.e. Easter) candles.

page 126 note 1 What are elsewhere called baldricks.

page 126 note 2 This word is written rather confusedly; and I am not sure it was not intended to be staples, or perhaps clasps.

page 129 note 1 Another word of doubtful meaning. In the dialects of the North of England a cather is a cradle.

page 129 note 2 ? knots.

page 131 note 1 i.e. cable.

page 131 note 2 The meaning of this seems rather obscure. Perhaps it means the two callends, or lichegates, the principal one, and that of the College, mentioned before.

page 132 note 1 Guild bell.

page 133 note 1 After-math.

page 133 note 2 Portman meadow is mentioned in all the churchwardens' accounts about this period. It appears that it was leased to Mr. Passie, and that some disagreement had arisen about it.

page 134 note 1 Soder.

page 136 note 1 A word of which I cannot give the meaning.

page 137 note 1 Low benches to stand on.

page 137 note 2 Tacka.

page 137 note 3 Perhaps for handelles.

page 138 note 1 Cheat.

page 138 note 2 Probably a local name of a measure.

page 139 note 1 The statute alluded to was that of 8 Elizabeth, chap. 15, “An Act for preservation of grain,” by which the churchwardens in every parish, with other persona to the number of six, were directed to provide for the destruction of "noyfull fowles and vermyn,” and a price was set upon their heads. A numerous list of the birds and vermin thus proscribed will be found in the Act.

page 140 note 1 Choughs.

page 141 note 1 One yard.

page 141 note 2 A walker meant a fuller.

page 142 note 1 Opposite.

page 143 note 1 Of course this entry relates to the rebellion in the North in 1569–70.

page 151 note 1 This word has not occurred before.

page 151 note 2 A hoop, a measure said to contain about four pecks.

page 151 note 3 For the plumber more, i.e. in addition to what he had been previously supplied with.

page 152 note 1 The plumber.

page 152 note 2 This is distinctly written in the original, but perhaps it is an error for baudrich, especially as “another” baudricke is spoken of in the next line.

page 153 note 1 This was the day of Queen Elizabeth's accession to the throne.

page 153 note 2 The gudgeons, or pins on which the wheels of the bells worked.

page 153 note 3 Hoops.

page 155 note 1 A paper book, probably.

page 157 note 1 Opposite.

page 158 note 1 The words within brackets are crossed out in the original.

page 159 note 1 The bier.

page 160 note 1 The surplices so often mentioned in these accounts were for the choristers, and some probably for the scholars of the Grammar School.

page 160 note 2 This was no doubt the liche-gate by which the churchyard was entered from Broad Street, on the site of what is still called the Callends.

page 161 note 1 A name of a measure which seems to be forgotten.