In spring 1766, Cécile-Thérèse-Pauline Rioult de Curzay (1707–87), Marquise of Monconseil, commissioned a vaudeville comedy for the Bagatelle, her estate on the outskirts of Paris.Footnote 1 The work, La fête du château, was conceived by the noted playwright Charles-Simon Favart, with music arrangement by the opéra comique composer Adolphe-Benoît Blaise.Footnote 2 The act of patronage was not in itself unusual for the wealthy and well-connected marquise. As a prominent salonnière – and mistress to a powerful statesman, Louis François Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu – Monconseil regularly marked court and society events with entertainments at her country home. What was outside the norm, in this case, was the occasion that the divertissement celebrated: Favart's opera commemorates the inoculation of the marquise's ten-year-old granddaughter, Cécile-Suzanne, against smallpox.Footnote 3

When La fête du château premiered, smallpox was a leading cause of global mortality – an excruciating illness that killed roughly 30 per cent of its victims and left countless others with permanent impairments. Inoculation, in turn, was a medical marvel of the Enlightenment, introduced to Europe via China, Africa and the Ottoman Empire in the early decades of the eighteenth century.Footnote 4 The preventative practice – which (ideally) induced an attenuated smallpox case and lifelong immunity through subcutaneous incision – held the potential to alleviate both individual and societal impacts of the disease. Nonetheless, it was fraught with controversy. (Unlike the later developed technique of vaccination, which deployed a comparatively mild cowpox virus, inoculation caused a true smallpox infection, posing a risk to the patient and their community.) The procedure faced particularly strong resistance in France. For much of the ancien régime, it was opposed by the Bourbon monarchs, banned within the walls of Paris and fiercely contested among royal administrators, physicians and philosophes.Footnote 5 The literary scholar Catriona Seth surmises, with only modest hyperbole, that in this period there were ‘seemingly more polemical texts circulated about smallpox … than people actually inoculated against the disease’.Footnote 6 La fête du château offers a fascinating window into this historical moment, recording a rare, private encounter with inoculation, as well as the cultural baggage that act elicited.

This article presents the first comprehensive account of La fête du château's origins and performance history, drawing on extensive archival material to elucidate the social and political repercussions of the Enlightenment inoculation debates – and the persuasive power of fashion, theatre and music within them.Footnote 7 Read within its initial production context, Favart's opera offers an intimate portrait of the Monconseil family's experience with the disputed procedure. The librettist had a long-standing personal relationship with his patron; his occasional work, accordingly, alludes to both the practical details of Cécile-Suzanne's treatment and the ways in which she and other members of her household were expected to benefit from it. La fête du château, in other words, serves as a sort of aristocratic conduct manual for the management of smallpox, demonstrating how Cécile-Suzanne's inoculation might bolster her marriage prospects, while solidifying her grandmother's reputation as an ‘enlightened’ champion of science and sensibilité. As such, the opera underscores the gendered tropes then accruing to the disease, as well as the significant – and traditionally undervalued – function of elite sociability in promoting novel techniques of its prevention.

Although La fête du château originated within the quasi-domestic sphere of the Bagatelle, it soon achieved success in public venues throughout France. From the late 1760s, it was incorporated into the repertory of the Crown-subsidised Comédie-Italienne, the primary Parisian theatre for opéra comique; and in the 1770s, it was showcased before the royal family at Versailles. Entirely overlooked until now, these court-sponsored performances had an unmistakable political valence, coinciding with Louis XV's death from smallpox in May 1774 and the highly scrutinised inoculation of his successor, Louis XVI, in the months that followed. This was a reversal of the monarchy's entrenched anti-inoculation stance, and a key turning point in France's battle against the virus. Notably, it was the queen, Marie Antoinette, who spearheaded the programming of Favart's comedy, a fact that sheds new light on this change in ancien-régime medical policy and the agency behind its implementation. As in other matters of privileged taste, Marie Antoinette was a compelling trendsetter in the realm of public health, with theatre an important tool in her fashionable arsenal.

Capturing the cultural traces of an epidemic – and the extent to which style, social networks and contemporary media structured responses to it – La fête du château is an opera with clear and continuing reverberations in the age of COVID-19.Footnote 8 I would argue, though, that the interest of the work lies both in and beyond its relevance to the history of medicine and its attention-piquing parallels to current events. This article situates La fête du château within a robust literature on early modern disease; more broadly, it contributes to a recent scholarly recuperation of amateur theatricality (théâtre de société) in the French Enlightenment.Footnote 9 The very name of Monconseil's estate – the Bagatelle – conjures an image of ‘feminine’ frivolity. And yet, the spectacles that originated there were substantive both in their dramatic aspirations and in their capacity to sway their audiences, exemplifying the serious implications of sociable music-making in eighteenth-century France.Footnote 10 The trajectory of La fête du château shows, quite strikingly, how a work conceived for a limited, private context might exert a sizeable public impact – expanding our perspective of the conditions under which ancien-régime opera took on political meaning and the role of women patrons and consumers in this process.

Monconseil, smallpox and the Château de Bagatelle

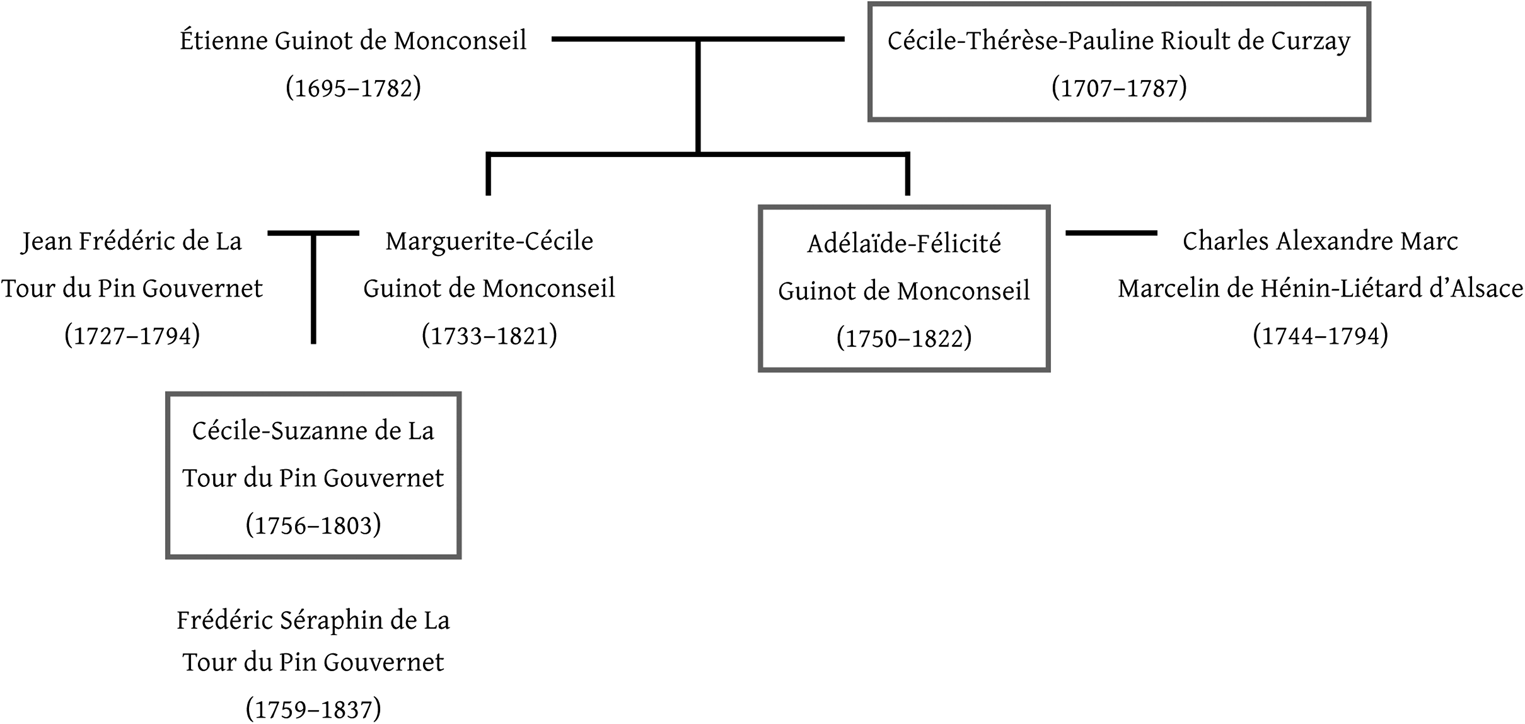

For a woman of her time and circumstances, the Marquise of Monconseil's life is fairly well documented. We are able to reconstruct the details of her familial and social networks, the development of her theatrical practice and the extent to which both were affected by the pervasive threat of smallpox. The Monconseil family papers, currently held at the French national archives, trace the basic outlines of her domestic circumstances.Footnote 11 The marquise was born into a wealthy family in Paris. In 1725 she wed Étienne Guinot de Monconseil, a member of the established nobility and a lieutenant general in the royal army. In the early years of their marriage, the couple was associated with the court of Stanislas I, Duke of Lorraine and King of Poland. (Monconseil forged her aristocratic connections as a dame du palais for Stanislas's wife, Catherine Opalińska.) While the marquis spent most of his career in provincial France – he was given a diplomatic appointment in Colmar in 1751 – the marquise ultimately returned to the capital. During her husband's multi-year absences, Monconseil enjoyed a largely independent existence. She divided her time between the Bagatelle estate and an apartment in central Paris, assuming primary responsibility for these residences and the extended family that inhabited them. (Monconseil had two daughters and several grandchildren; her family tree is included, for reference, in Figure 1.Footnote 12)

Fig. 1. The Monconseil household in 1766. (Boxes denote family members referenced in La fête du château.)

Court memoirs and correspondence reveal that the marquise was a fixture of elite society in the years around mid-century. At Versailles, she enjoyed the rights to dine and ride in carriages with Louis XV's queen, Marie Leszczyńska – enviable privileges in a hierarchy based upon access to the monarchs.Footnote 13 She also entered into several high-profile romantic liaisons: in addition to her relationship with the military official Richelieu, she was briefly linked to the minister of war, Marc-Pierre de Voyer de Paulmy, Count of Argenson.Footnote 14 As Monconseil engaged in the public life of the court, she cultivated a well-regarded salon at the Bagatelle, surrounding herself with a coterie of liberal aristocrats and artistic notables; her most famous guests were ‘enlightened’ royals, including her former employer, Stanislas I, and Louis Philippe I, Duke of Orléans.Footnote 15 Such was the marquise's standing that the British diplomat Lord Chesterfield recommended her gatherings as among the most erudite in France: ‘You will find at Paris good authors, and circles distinguished by the solidity of their reasoning. You will never hear TRIFLING, AFFECTED, and far-sought conversations, at Madame de Monconseil's.’Footnote 16

These legal records and scattered court recollections provide a preliminary picture of Monconseil's status among the lettered nobility of the late ancien régime. By far the most important source for the marquise's personal experiences and artistic influence, however, is a somewhat unusual set of documents: an annotated collection of the dramatic works she commissioned to entertain her guests – and shape her social reputation – at the Bagatelle.Footnote 17 At the height of the marquise's patronage activities (from roughly the mid-1750s to the mid-1760s), theatre was a prominent attraction at the Monconseil estate, presented alternately in a drawing room within the château and a seasonal structure in its gardens.Footnote 18 Two principal features of these spectacles are worth underscoring here. First, the Bagatelle manuscripts suggest that the literary and performance standards of the marquise's productions were quite sophisticated, reflecting the porous boundaries between modes of ‘society’ and ‘public’ theatricality. The repertory of the Bagatelle, for example, was closely aligned with that of the prestigious Comédie-Italienne; Favart adapted opéras comiques from the Crown company for Monconseil's use and also, conversely, allowed his private commissions to be transferred to the Parisian stage.Footnote 19 These spectacles, moreover, relied upon a mix of professional and amateur talent; the marquise employed leading actors from the royal troupes, such as Marie-Justine Favart and Silvia Balletti, to appear alongside members of her household in performances.Footnote 20

Second, the divertissements of the Bagatelle exemplify the elisions between art and life that arose in the practices of pre-revolutionary théâtre de société. On a logistical level, Monconseil's theatrical activities were deftly interwoven into the quotidian rhythms of recreation at her estate. An afternoon's entertainment might feature a ‘formal’ opera or spoken play alongside looser dramatic sketches, songs, card games, refreshments and literary discussion.Footnote 21 On a textual level, these works contain an abundance of information about the marquise, her family and acquaintances, from their personal affairs to their perspectives on politics and current events. Even ostensibly fictionalised pieces are topical in scope, and littered with allusions to happenings in the marquise's social circle. In this collection we find spectacles celebrating the weddings of Monconseil's children and the births of her grandchildren;Footnote 22 poetry praising her illustrious visitors;Footnote 23 and elaborate dramatic reflections on French victories in the Seven Years’ War.Footnote 24 Favart's correspondence indicates how closely he tailored this output for the people and occasions that it commemorated. In one undated letter, for instance, the playwright admonished Monconseil for not having provided enough detail about a friend for whom she desired a set of laudatory couplets:

You have recently asked me to write a poem about a distinguished man by the name of Louis. … But you haven't truly described to me the character of this person, nor given a full account of the deeds that he has accomplished. A set of couplets for someone must be specific to them, and not devolve into clichés – these must not be a saddle for any horse, so to speak. … I therefore ask of you, Madame, to be so kind as to instruct me a little further about how to properly celebrate your hero, and not to spare those little insights that might lend substance to these praises.Footnote 25

Monconseil's manuscripts thus provide insight into the lives of the aristocrats and intellectuals that gathered at the Bagatelle, as well as the literary and philosophical issues that animated them. In so doing, they attest to the inseparability of sociability and substantive discourse within her theatrical pursuits – a conceptual tension that lies at the foundation of recent studies of the théâtres de société (and the historiography of Enlightenment salons, more broadly).Footnote 26

Though smallpox might seem a surprising dramatic subject, several of Monconseil's commissions responded to contemporary anxieties about the illness and controversies over its treatment, and it was in these works that the personal and political facets of her theatre most closely coalesced. It is clear that the marquise's société had been intimately affected by the disease, reflecting the ever-present dangers it posed to the inhabitants of eighteenth-century France. The first Bagatelle divertissement of which we have record, dating from c.1756, marked the recoveries of two close family members – Monconseil's sister, Marie Rioult de Curzay, and niece, Cécile-Pauline-Marie d'Ennery – from the virus. The work articulates the trauma these women had suffered; one chanson compares smallpox to ‘a monster escaped from hell / and driven by vengeance / infecting the air with its breath / and pouncing upon’ its prey.Footnote 27 Such ‘monstrous’ imagery was not inappropriate, for smallpox was a truly terrifying illness. Its victims endured debilitating symptoms (fevers, haemorrhaging, swelling so severe it might render them unrecognisable), and were often plagued by lifelong after-effects (scarring, vision problems, the loss of hair and eyelashes). Nor did the text of the song exaggerate in its ‘predatory’ metaphors. Paris and its environs had been struck by devastating waves of infection throughout the ancien régime; an epidemic in Monconseil's adolescence, for example, had claimed some 20,000 of the city's residents – roughly 1/25th of its total population.Footnote 28

If smallpox was a pressing, individualised concern for Monconseil and her associates, inoculation was a subject of widespread societal debate. The procedure had been recognised and contested in France since the early 1720s – the moment of its famed ‘introduction’ to Europe by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.Footnote 29 While the preventative practice was steadily adopted throughout Montagu's native Britain, it faced significant and enduring scepticism across the channel. Several factors contributing to the French hesitancy were ideologically rather than scientifically grounded, relating to the personal resistance of the monarchs and the entrenched conservatism of the Parisian Faculté de Médecine.Footnote 30 But these political incentives intersected with legitimate medical and moral uncertainties. Although most inoculated patients developed a mild expression of smallpox, some experienced very serious illness (and even death); they also remained contagious throughout their treatment, capable of seeding outbreaks within their households (and beyond).Footnote 31 Inoculation was simultaneously, then, a miraculous breakthrough and a source of excruciating ambiguity. It raised fraught questions regarding the ethics of imposing sickness on healthy individuals (especially children), and the tensions between familial and communal assumption of benefit and risk.

Inoculation became a cause célèbre in progressive French salons of the mid-eighteenth century, for the most prominent advocates of the technique were not physicians but literary figures and philosophes.Footnote 32 Voltaire established a persistent link between medical innovation and the politics of the Lumières with an essay, ‘On the Engraftment of Smallpox’ (‘Sur l'insertion de la petite vérole’), in the Lettres philosophiques of 1734.Footnote 33 Pro-inoculation arguments – also set forth by luminaries such as Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert – brought together several prominent themes of Enlightenment discourse. Certainly, support for inoculation aligned with support for scientific progress, writ large; Diderot's article for the Encyclopédie hailed inoculation as the ‘greatest medical discovery ever made, with regards to the preservation of human life’.Footnote 34 The choice to submit to the procedure, along similar lines, could be justified through objective statistical principle – accepting the calculated risk of the prophylactic to avoid the ‘random cruelty’ of full-fledged disease.Footnote 35 As inoculation appealed to ‘enlightened’ rationality, so too were defences of the practice steeped in the contemporary rhetoric of sensibilité. The philosophes reinforced their claims to logical authority by invoking ideals of sentimental, domestic duty. The mathematician and Encyclopédiste Charles Marie de La Condamine, for example, argued that protecting one's children through inoculation was an act of ‘enlightened love’ – a turn of phrase that encapsulated the duality of reason and feeling at the heart of the Enlightenment project.Footnote 36

The earliest French adopters of inoculation were social elites invested in these reform-minded values: members of the privileged urban classes in general, and adherents of Monconseil's salon in particular. At the vanguard was the Duke of Orléans, who inoculated his children to great fanfare in spring 1756.Footnote 37 Orléans sought to solidify his reputation as a foil to his reactionary cousin, Louis XV, earning public accolades and numerous printed panegyrics in the process. A poem from the librettist Antoine-Alexandre-Henri Poinsinet emphasised the judiciousness of the duke's decision, which had secured him the esteem of all ‘enlightened’ Frenchmen:

The royal inoculations made a celebrity of Théodore Tronchin,Footnote 40 the doctor who performed them, and sparked admiration among other notable visitors of the Bagatelle.Footnote 41 As Voltaire quipped of Septimanie d'Egmont (the daughter of Richelieu, and a member of Monconseil's inner circle), the practice became such an indication of taste that those with natural immunity regretted their exclusion: ‘I believe that Madame the Countess of Egmont has already had smallpox. That's really too bad. If she hadn't, we could have inoculated her, and had an excuse to throw a nice fête.’Footnote 42

In 1766, when Cécile-Suzanne was inoculated at the Bagatelle, the practice still stood outside the ancien-régime medical mainstream. But the marquise's granddaughter was a member of a demographic at the forefront of the procedure's adoption – and she made an impact that would be felt well beyond her privileged sphere.Footnote 43 La fête du château is a revealing record of these private events, as well as the nascent public-health movement in which they took part. In explicating the experiences of the Monconseil family, the work concretises the abstract stakes of the contemporaneous inoculation debates, while illuminating the themes of a ‘literary imagination’ then consolidating around smallpox. More important, it forecasts how a wider French public would ultimately be convinced of the treatment's effectiveness: not through scientific discourse, but through popular culture – and in particular, through gendered appeals to beauty, marriage and sentiment.

‘Un mal qui fait du bien’: reading Favart's opera

La fête du château is the only extant evidence of Cécile-Suzanne's inoculation. (There are no payment records for the treatment in the Monconseil family papers, or mentions of it in contemporary correspondence.Footnote 44) Given the nature of Favart's other commissions for the marquise, however, it is reasonable to assume that the opera references specific household incidents at the Bagatelle, as well as the manner in which Monconseil fashioned her self-image in this domestic domain. In structure and basic plot conventions, La fête du château is typical of the author's mid-century style: it features dialogue interspersed with re-texted popular airs (vaudevilles), and nimbly interweaves a series of comic intrigues. The action unfolds at an estate in the French countryside. At the outset, the household staff prepares a party for their young mistress, Lise, who has just recovered from her smallpox inoculation. As they organise the festivities, the servants become entangled in romance: Madame Jordonne, the concierge of the château, pursues Jacquot, the gardener, who is in turn enamoured of Colette, the daughter of a local farmer. Colette reciprocates Jacquot's sentiments but is hesitant, for her father disapproves of the match. After several light-hearted misunderstandings, the lady of the house sets the proceedings aright. She encourages Colette to marry Jacquot and blesses a new suitor for the jilted Madame Jordonne: the doctor who performed the inoculation.

A number of the allusions in Favart's libretto are self-evident. The estate setting is a stand-in for the Bagatelle; the ‘dame du château’ and the recuperating protagonist are doubles for Monconseil and her granddaughter, respectively. From the fictional Lise's experiences, we can infer some details about the real-life Cécile-Suzanne. The text implies that the inoculation took place in April, when weather was thought to be optimal for the procedure.Footnote 45 It also relates that the patient fell ill for several weeks, a glimpse of the dangers involved.Footnote 46 While the opera's two planes of action (a serious medical situation; a good-humoured love story) might seem incongruous, such a mix of concerns also had a basis in fact. As Monconseil arranged for her granddaughter's inoculation, she was simultaneously preoccupied with the engagement of her youngest daughter, Adélaïde-Félicité. (Adélaïde-Félicité was Cécile-Suzanne's aunt; she was set to wed Charles Alexandre Marc Marcelin de Hénin-Liétard d'Alsace, Prince of Hénin, in autumn 1766, just a few months after La fête du château premiered.Footnote 47) Although Favart's romantic ingénue, Colette, is not of noble birth, she is a highly sympathetic character and central to the work's plot; it is no coincidence that her age and dramatic situation – fifteen years old and on the brink of marriage – precisely match those of Adélaïde-Félicité.Footnote 48 In all, the opera celebrates the health of one family member, the nuptials of another and the magnanimity of their matriarch, who facilitated both.

If La fête du château references the material circumstances of the Monconseil household at the time of Cécile-Suzanne's inoculation, it also sheds light on the social implications of the practice among the nobility of eighteenth-century France. Put another way, the opera records both the details of the marquise's domestic choices and the idealised ways she wished to represent these choices to her family and circle of acquaintances. One clear goal of La fête du château is to praise Monconseil for her management of the Bagatelle. The ‘dame du château’ goes unnamed within Favart's libretto and appears only once in the course of the work: during the concluding divertissement, she stands on the balcony of her manor home, supervising the musical festivities below. (Given the fluid boundary between professional and amateur performers in the private context, it is likely that Monconseil filled this role herself.) While the physical presence of the ‘dame du château’ is downplayed, her altruistic influence is foregrounded throughout. The other characters praise her progressive support for inoculation; they also commend her financial generosity towards the inhabitants of her estate and her emotional investment in their welfare (as demonstrated in a dowry and in romantic counsel that she provides to Colette). La fête du château thus situates a pro-inoculation stance within the paradigmatic constellation of traits possessed by an ‘enlightened’ noblewoman – and establishes the marquise, in turn, as an aspirational model thereof.

La fête du château holds its most pointed lessons for the young women of the Bagatelle – the group actually being asked to submit to inoculation. The libretto reassures this target audience by glossing over the most distressing symptoms of smallpox, as well as the worst risks of its treatment. Although there are references to the hardships that Lise has faced, the action begins after she has emerged unscathed from her procedure, and her companions express complete confidence in the path that she has undertaken. In the opera's opening scene, the doctor voices befuddlement that anyone would be opposed to inoculation. Given that the ‘science’ has ancient roots and has recently been ‘perfected’ in England, there is little reason to doubt its safety. This encouraging tone is reinforced by the musical language of the comedy – the anxieties of inoculation defused in the popular, singable idiom of the vaudeville. As the doctor confirms – in catchy, major-mode refrain, no less – the treatment is ‘one harm that does good’ (‘un mal qui fait du bien’).Footnote 49

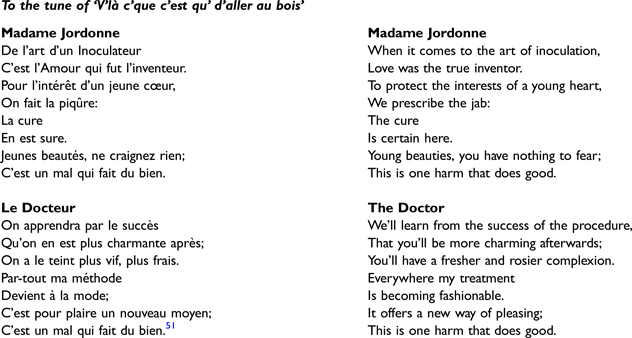

Favart's overwhelming emphasis, instead, is that inoculation might render a woman more desirable to her suitors – eliding ideals of beauty, bodily health and sexual purity. As the doctor notes in an air on the tune of Jean-Philippe Rameau's ‘Dans ce couvent’, his primary responsibility is ‘to make a girl sweeter than ever’ (‘rendre une fille / plus gentille / que jamais’).Footnote 50 The sentiment is articulated more explicitly in the subsequent number, a duet between the doctor and Madame Jordonne that takes the form of a jaunty gigue (Example 1):

In this musical extract, the primary advantage of inoculation is construed as aesthetic – and strongly and quite patronisingly gendered. The procedure saves its (female) beneficiaries from the disfiguring effects of smallpox, thereby ensuring their romantic prospects and implied social capital.Footnote 52 Here and throughout the opera – echoing literary tropes then consolidating around the disease – Favart draws links between inoculation and marriageability, and between the transmission of illness and ‘infection’ from love.Footnote 53 The quoted duet makes a gentle innuendo out of the ‘jab’ (‘piqûre’) of Lise's treatment; elsewhere Colette remarks upon the physical distress her sentiments for Jacquot evoke, and the curative relief she experiences upon their reconciliation.Footnote 54 The two heroines of La fête du château (the convalescent and the ingénue), along with their counterparts in the Monconseil household, thus represent two interconnected ideals of Enlightenment femininity. The action the younger woman takes to safeguard her health, Favart suggests, will enable her to attain the prize sought by her elder compatriot: the security of an auspicious union.

Example 1. C.S. Favart, La fête du château, scene 1, ‘De l'art d'un Inoculateur’.

La fête du château is, to be sure, a wildly inaccurate portrait of the ravages of smallpox. Thwarted romantic affairs were not the gravest consequences of the lethal virus, nor were its traumatic impacts and experimental treatments borne primarily by white, privileged Parisian women.Footnote 55 And yet, the limitations of La fête du château belie the significance of its underlying concerns and the eventual extent of its influence. To start, the opera's focus on beauty should not be read as purely superficial – but rather as a euphemistic gloss on the very serious risks of disfigurement from the disease. As David E. Shuttleton has outlined, such physical repercussions of smallpox were viewed with distinct alarm in the rigidly hierarchical society of the ancien régime. Bluntly put, ‘attractive daughters were more marketable daughters … serving as trafficable commodities through which a propertied patriarchy sought to cement economically and politically advantageous dynastic ties’.Footnote 56 The women of the Monconseil family were undoubtedly affected by these pressures; the marquise appears to have gone to great lengths to arrange elite marriages and court positions for her daughters and granddaughter – likely the most stable life path available to them. More generally, it bears emphasising that La fête du château did not have to be fully truthful or representative to be widely consequential. During this period, there was considerable slippage between literary and scientific depictions of inoculation: novels frequently featured ‘medical episodes’ to ‘help readers come to terms with modern developments’, while medical texts deployed poetic and epistolary devices to amplify the emotional impact of their arguments.Footnote 57 In such cases, ‘prettified’ depictions of smallpox and its victims nonetheless played a role in shaping real-world attitudes towards the disease. Indeed, as the reception of Favart's comedy affirms, a work that blended fact and fiction might exert a powerful effect on – and leave a striking picture of – the society that absorbed its message.

La fête du château in Paris and Versailles

From its very origins, La fête du château gestured beyond the confines of the Bagatelle. Its plot was meant to bolster Monconseil's image within her courtly social network, while its vaudeville melodies were drawn from, and subsequently recirculated within, the urban soundscape of the French capital.Footnote 58 Yet Favart's opera assumed a more explicitly ‘public’ function in September 1766, when it entered the repertory of the Comédie-Italienne. (The transfer probably occurred through the connections of the librettist.) The work was favourably reviewed in the Parisian press, and regularly revived in the decade thereafter.Footnote 59 The critical and commercial success of La fête du château suggests that, as the comedy moved into the ‘official’ domain, it began to reflect – and also provide impetus to – larger changes in French opinion surrounding the medical practice. Although the Comédie-Italienne was a Crown-affiliated institution, it served a relatively broad and heterogeneous audience in the capital. The Hôtel de Bourgogne, the company's theatre, accommodated roughly 1,500 spectators, split between wealthier, box-holding patrons and the socially mixed crowds of the standing-room pit, or parterre.Footnote 60 The Parisian production of La fête du château reiterated pro-inoculation arguments to many members of an already converted group (noblemen and intellectuals familiar with the medical controversy from its ubiquity in the press and in mid-century salons). But this sympathetic portrayal of inoculation also undoubtedly served some sceptical viewers (and viewers who lacked access to other media in which this discourse circulated). A number of journalists, indeed, used the occasion to editorialise in favour of the treatment. The Journal encyclopédique, for example, briefly diverted from its plot summary to reflect on the ‘marvels of inoculation’,Footnote 61 while the Mercure de France drew attention to ‘the useful and very prudent procedure’ that formed the impetus for Favart's comic action.Footnote 62

It seems, notably, that the unique conditions that inspired Monconseil's commission contributed to, rather than detracted from, its potential utility in a broader public-health campaign. In her discussion of the pro-inoculation philosophes, Meghan K. Roberts remarks that these authors self-consciously drew domestic practices into the field of public discourse, framing their scientific defences of inoculation with personal anecdotes about their own experiences with smallpox and its prevention. This rhetorical strategy, Roberts points out, not only ‘made texts comprehensible and persuasive’ but also ‘helped associate new procedures with social elites, which informed the reader of the many royal, noble, and otherwise illustrious parents who had inoculated their children and presumably hastened its wider adoption’.Footnote 63 The inspiration, plot and reception of La fête du château together offered a more tangible – and arguably even more compelling – demonstration of this trajectory. The characters within the opera quite literally sang the praises of inoculation, vouching for its utility before the nightly audiences of the Comédie-Italienne. The work's reviewers, in turn, emphasised the true-to-life sentiments behind Favart's theatrical message, linking the treatment to the virtuous Monconseil women and their fashionable home. The Correspondance littéraire lauded the inoculated patient's beauty as ‘deserving of celebration by all of our poets’;Footnote 64 the Mercure de France described her treatment as a symbol of how much she was ‘cherished by her family’.Footnote 65 The effect was to bridge the gap between the publicly staged fiction and the private reality at its foundation, presenting an enviable model for the growing body of spectators that consumed it.

While the influence of La fête du château was strongly felt in Paris, it held a more overt political significance at Versailles. As we have noted, Louis XV was a vocal hold-out in the wider adoption of inoculation, among the progressive nobility within France and among European monarchies more generally.Footnote 66 His hostility was partially rooted in international affairs – in particular, in the acrimonious diplomatic relationship between France and Britain after the Seven Years’ War. Inoculation was strongly associated with English physicians, which precluded its full acceptance at the rival court. A more personal – and ultimately harmful – rationale for the monarch's conservatism was the mistaken belief that he had been struck by smallpox as a teenager, and thus held immunity to the disease. That Louis XV had vanquished an illness that felled so many others became an important component of his heroic self-image. A poem published during the king's youthful convalescence, for instance, likened inoculation to the ingestion of foreign poison,Footnote 67 an action rendered unnecessary by the sovereign's providential bodily attunement and self-control: ‘Louis shows his fellow men that in every sort of duty / the conqueror of himself is the one true hero’.Footnote 68 The king, in other words, had no need for inoculation because he had been endowed with an inner strength that surpassed that of the citizens he ruled.Footnote 69

The governmental status quo was called dramatically into question in April 1774, when some fifty courtiers were infected in an outbreak at Versailles. On the 28th of the month, Louis XV felt unwell and developed a fever. His attendants at first downplayed their alarm, taking solace in the assumption that his adolescent illness would protect him from harm. (The king was reported to have claimed from his sickbed: ‘if I hadn't had smallpox at eighteen, I would think I had it now!’Footnote 70). Within days, however, the error of the previous diagnosis, as well as the gravity of the situation, became apparent. On 30 April the revised judgement, petite vérole, was announced at court and in the capital, and Louis XV's three grandsons – the only direct heirs from the Bourbon line, all of whom remained vulnerable to the disease – were sent away from the monarch's bedside. Despite the intensive efforts of the Crown physicians, the king's condition deteriorated quickly: he died less than two weeks after the appearance of his first symptoms, on the afternoon of 10 May. During the rapid course of the illness, it was the Duke of Orléans's son, the Duke of Chartres, who brought news from the royal bedchamber to the sequestered dauphin – a benefit of the immunity acquired from his own inoculation two decades prior.Footnote 71

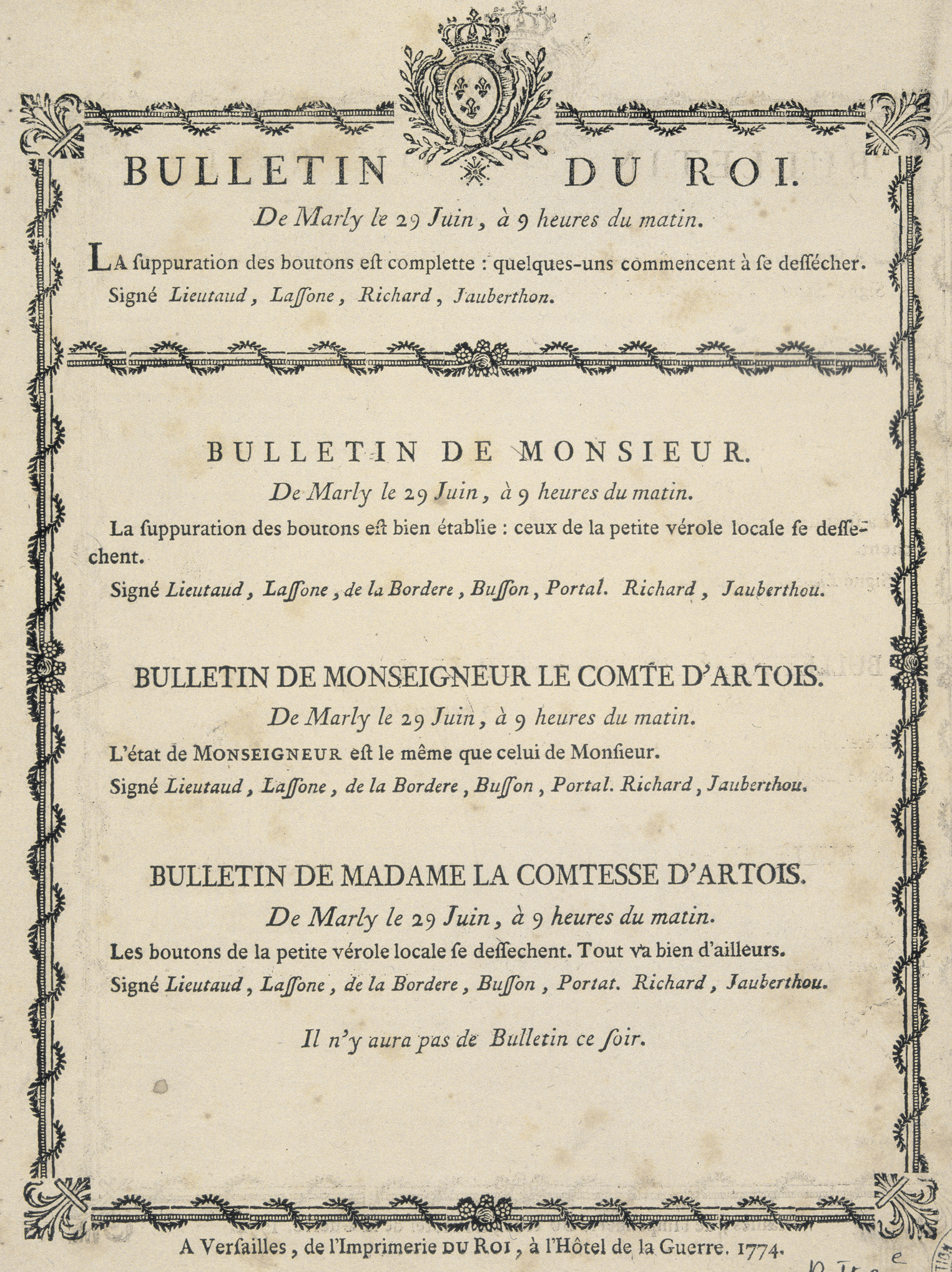

The sudden death of the monarch, and the manner the Versailles outbreak laid bare the vulnerability of the Bourbon heirs, immediately altered official attitudes towards smallpox prevention in France. The new king and his siblings, long-time sceptics of the procedure, agreed at last to be inoculated, and retreated to quarantine at the summer château of Marly by mid-June. The abrupt about-face elicited a storm of controversy – a result of the precedent the monarchy itself had so publicly set. Marie Antoinette's lady-in-waiting, Madame Campan, noted that ‘many Parisians were in a state of alarm’ at the news of the impending procedure;Footnote 72 the Mémoires secrets reported that the royal decision had occasioned a ‘new round of debates over the method, which still has numerous opponents in France’.Footnote 73 (Such was the atmosphere of uncertainty that the stock market plunged precipitously in the days leading up to the inoculation.Footnote 74) Fortunately, the treatment proceeded as smoothly as governmental administrators might have hoped. ‘The smallpox infection has done little to disturb the habitual activities of the king’, wrote the Austrian ambassador, Florimond-Claude, Count of Mercy-Argenteau, to the Empress Maria Theresa in Vienna. ‘Throughout their stay in Marly, [the members of the royal family] have spent their days strolling in the gardens, and their evenings playing billiards and cards.’Footnote 75 A bulletin from the king's physicians announced his recovery on 29 June (Figure 2).Footnote 76 In the two short months since the onset of Louis XV's illness, the French monarchy had undergone a thorough, contested – and ultimately widely influential – transformation in its approach to the management of the disease.

Fig. 2. Medical bulletin announcing the inoculation and recovery of Louis XVI (Marly, 29 June 1774). Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, Versailles, France. RMN – Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY (Gérard Blot). (colour online)

It was in this politically fraught context that La fête du château came to prominence at Versailles, broadcasting the reorientation in French public-health policy.Footnote 77 The most vehement advocate for Louis XVI's inoculation seems to have been his wife, Marie Antoinette. (The Habsburg court had been gravely affected by smallpox during the queen's childhood, firmly converting Maria Theresa and her family to the pro-inoculation cause.Footnote 78) Marie Antoinette was also clearly behind the programming of Favart's opera: her support for the comedy can be documented on multiple occasions across a variety of venues. In winter 1775, for instance, she sponsored a visit to Versailles by her younger brother, the Archduke Maximilian of Austria. The diaries of Denis-Pierre-Jean Papillon de la Ferté, the intendant of the royal household, relate that Marie Antoinette was enthusiastically involved in the planning of balls and spectacles for the occasion, including a performance of La fête du château in the salon d'Hercule on 15 February.Footnote 79 The queen would continue to patronise Favart's work for at least the remainder of the decade, developing an enduring association with its central message. She presented La fête du château at her personal theatre at the Petit Trianon in 1777, an explicit gesture of approval before her inner circle of associates.Footnote 80 That same year, she journeyed to the capital to take in a performance at the Comédie-Italienne – her highest and most public form of artistic endorsement.Footnote 81

This theatrical promotion of inoculation was important for the queen's personal politics. Throughout the Versailles outbreak, Marie Antoinette's behaviour had been scrupulously dissected by proponents and critics alike, interpreted (for better or for worse) as a demonstration of her character and readiness to rule. Her pious loyalty at Louis XV's bedside had earned her measured praise, resonating with gendered expectations of caregiving and sentiment. Mercy-Argenteau reported that Marie Antoinette had ‘displayed the conduct of an angel’ while tending to the stricken king, ‘enchanting the public’ with her martyr-like devotion to her sovereign.Footnote 82 Shortly thereafter, however, rumours that she had pushed Louis XVI towards inoculation drew intense scrutiny (at least before the successful outcome of the treatment), playing into xenophobic concerns over her lingering Austrian allegiances.Footnote 83 Critics portrayed Marie Antoinette's influence over her husband's decision as a poorly reasoned and perniciously foreign intervention into the affairs of state. As Campan recalled, those who opposed inoculation ‘hastened to blame the error on the new queen – she being the only one, it was said, who could have given [Louis XVI] such reckless advice’, based on her upbringing in a ‘northern court’.Footnote 84 La fête du château, then, was doubly useful in burnishing Marie Antoinette's reputation, for its plot amplified actions for which she had been commended, while addressing points of recent censure. As Favart's opera reflected well on the Monconseil household, so too did it glorify the queen on a grander stage – lauding her composure in the face of tragedy and vindicating, in hindsight, the good sense of her pro-inoculation outlook.

Louis XVI's inoculation – and the queen's marketing thereof – also had broader political implications, marking the end of the most tendentious ancien-régime debates over the practice. The monarchy's belated acceptance of the procedure paved the way for some pragmatic, state-sponsored programming; by the 1780s, for example, children began to be inoculated at government charity hospitals, making the preventative treatment more accessible beyond the aristocratic networks in which it had first gained traction in France.Footnote 85 Less directly measurable, though equally noteworthy, was a shift in the tenor of public discourse: the Crown-sponsored performances of La fête du château signalled the moment when inoculation fully entered the French cultural mainstream. Alongside her theatrical sponsorships, Marie Antoinette famously incited a vogue for the pouf à l'inoculation – an elaborate hairstyle featuring a serpent, a club and a rising sun (symbolising medicine, conquest and Louis XVI's recovery, respectively).Footnote 86 Trend-conscious Parisians soon followed suit, declaring their support for the procedure by sporting hats adorned with pox-speckled ribbons (Figure 3), or collecting porcelain figurines after the protagonists of La fête du château (Figure 4).Footnote 87 As Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell has argued, the example of smallpox inoculation powerfully demonstrates the ‘interdependence of fashions and ideas in the eighteenth century’.Footnote 88 The practice had been granted initial credibility through the advocacy of scientists and intellectuals; and it subsequently gained practical support through the evolution of governmental policy. Yet it would only attain widespread acceptance in France after it was thoroughly embedded in the cultural psyche – celebrated as both safe and stylish by the figureheads of the consumer marketplace.

Fig. 3. Nicolas Dupin, Gallerie des modes et des costumes français dessinés d'après nature (45e cahier, 1785). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (colour online)

Fig. 4. Étienne-Maurice Falconnet, figurine in soft-paste biscuit porcelain depicting Colette and Jacquot in La fête du château. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. (colour online)

The politics of the Bagatelle

La fête du château offers insight into the development of French attitudes towards smallpox inoculation in the late eighteenth century: its trajectory parallels the procedure's bumpy path to acceptance and emphasises the role that popular cultural artefacts played in this process. In so doing, Favart's comedy also testifies to the wide-ranging influence of the theatrical activities of the domestic sphere – and the women who took part in them. Historians of medicine have described a gendered gap between the prescriptive literature on inoculation and the logistical initiative vital for its adoption. While public debates on the subject were dominated by men, the weighty decision to inoculate members of a household was often taken on privately by women. An analogous disjuncture might be seen in ancien-régime expectations of artistic practice. Critical and didactic writings of the Enlightenment period tend to portray women as passive consumers of music; but they exerted independent initiative within their social milieux, with consequences that resonated far beyond this domain. Both of these corrective trends are substantiated in the production and reception of La fête du château. Within their respective families, it was the Marquise of Monconseil and the Queen Marie Antoinette who most forcefully advocated for the medical procedure – and then moved to affirm and advertise that choice through progressive musical patronage.

Recent scholarship on the théâtres de société – and on amateur music-making, more generally – has emphasised the ‘liminal status’ of both physical venues of performance and the repertory they showcased. Rebecca Cypess, for example, suggests that it was the inherent ‘ambiguity’ of Enlightenment salons that facilitated women's cultural agency within (and outside of) these spaces. The quasi-domestic positioning of the salon allowed women to ‘exercise their taste, influence, and talents’ in ways that did not threaten the perceived limitations of their gender and that might thereafter ‘spill out’ into the public sphere.Footnote 89 The case of La fête du château demonstrates, along similar lines, how elite women's operatic patronage served as a means of entry into a field of discourse that otherwise excluded them. Going one step further, it underscores that this process operated not solely in artistic, but also in explicitly political terms. Indeed, I would argue, Favart's comedy achieved its impact precisely because of its ‘liminality’ – by thwarting bifurcated conceptions of ‘serious’ and ‘sociable’ register, while collapsing divisions between the theatre and the world beyond the stage.

The form of La fête du château, as well as the circumstances of its commission, enabled it to function simultaneously as a ‘mirror and deflection’ of wider societal concerns.Footnote 90 As we have traced, the ‘amateur’ status of Monconseil's theatre belied the prominence of its actors and audiences. Venues such as the Bagatelle were effective testing grounds for contentious philosophical and political ideals because they were granted greater autonomy than the ‘official’ dramatic institutions of the ancien régime.Footnote 91 (Works on controversial subjects often premiered on private stages to smooth their path towards adoption by the nation's royally sanctioned companies.) The evidence suggests, moreover, that the domestic origins and topical inspiration of Favart's comedy, instead of detracting from its broad legibility, formed an essential facet of its appeal. La fête du château made a persuasive case for inoculation because it eschewed the abstract grandeur of courtly opera. Through its accessible musical language, it deflated the fears that surrounded smallpox; through its allusions to real people and events, it portrayed new techniques of disease prevention as at once attainable and fashionably aspirational. The success of La fête du château highlights the degree of ‘performativity’ inherent – then as now – in submitting to a medical procedure with communal, rather than strictly individual, benefit. For Monconseil and Marie Antoinette, support for Favart's inoculation-themed opera was an act equally of public relations and of public health – but the motivations of the former did not preclude the efficacy of the latter.

Favart's occasional commissions have received relatively little attention within the larger revival of interest in his plays and opéras comiques. Yet the librettist viewed these works as a critical component of his output – and, notably, the one that best reflected the political landmarks of his lifetime. In November 1774 – as La fête du château was prepared at Versailles – Favart described his achievements in a letter to Monconseil. ‘I have now been writing for more than forty of my sixty-four years’, he noted. ‘And in this time there has hardly been an important national milestone that I have not celebrated.’Footnote 92 The list Favart supplies his patron is lengthy, spanning several decades of current events and courtly intrigue: Les amours grivois for France's victory in the battle of Fontenoy; Le bal de Strasbourg for a youthful Louis XV's recovery from illness; topical commentaries for the birth of the Duke of Burgundy, and the wedding of the dauphin. Those who accused him of frivolity, Favart argues, underestimated the potential of such entertainments. The librettist recalls the success of Le mariage par escalade (Monconseil's tribute to Richelieu during the Seven Years’ War). He claims that the opéra comique was so stirring that ‘the hearts of all those in attendance were in a state of delirium – to the point that four tailors, two wigmakers, and a cutlery maker went directly from the spectacle to the recruitment office’, to offer their services to the illustrious general.Footnote 93

Although Favart's anecdote is patently hyperbolic, his larger point is not: intimate, personal engagement with a dramatic repertory and relevant ties to contemporary circumstances made it more affecting, and not less. ‘This goes to show’, he concludes, ‘that these bagatelles might well be good for something.’Footnote 94 Here Favart refers, of course, to both the Monconseil estate and the spectacles that flourished there. Light-hearted though it may be, Favart's play-upon-words encourages us to take seriously the implications of sociable patronage, as a critical (and neglected) lens on the cultural politics of the French Enlightenment.

Acknowledgements

For their editorial assistance and generous comments, I would like to thank Callum Blackmore, Rebecca Dowd Geoffroy-Schwinden, the members of the 18th-Century France Working Group (Columbia/NYC) and the anonymous readers for this journal. Support for this project was provided by a Lenfest Junior Faculty Development Grant from Columbia University.