I. Introduction

In November 2020, in the shadow of Brexit, and the emerging potential for the UK to take control of its financial services laws and regulations, HM Treasury commenced a review into the competitiveness of the UK's listed company regime.Footnote 1 It would be undertaken in the context of traditional industries being displaced by high-growth technology, e-commerce and science companies,Footnote 2 with a view to encouraging “more high-quality UK equity listings and public offers”.Footnote 3 Jonathan Hill, as chair, solicited views and evidence on, inter alia, free-float requirements, prospectus regulations, and, crucially, dual-class shares structures. A dual-class shares structure is where a company issues two (or more) classes of shares, with at least one class having attached to it a disproportionately high level of voting rights (rights to vote at a general meeting of shareholders) as compared to cash-flow or equity rights (rights to dividends or distributions upon a winding-up). Dual-class shares therefore enable a founder of a company to list its company, sell a majority of the existing shares on the public markets, and raise finance for future growth, without losing control. Such a structure can be especially beneficial for high-growth companies from the tech-sphere, since founders may, even upon listing, desire to retain control of the company to pursue an idiosyncratic visionFootnote 4 which is not easily observable to the public markets. With control, a founder can cause the company to invest in research and development and other long-term initiatives without fear of removal from the company by the public shareholders or by a predatory acquiror subsequent to short-lived periods of low share price. However, until recently, the most prestigious segment of the London Stock Exchange (LSE)'s Main Market, the premium tier, was hostile to dual-class shares, implementing an effective prohibition when the segment was created.Footnote 5

The concept of dual-class shares pervades the current UK regulatory discourse.Footnote 6 The conclusions of the UK Listing Review (the “Review”),Footnote 7 published in 2021, appeared finally to climb the steep hill to relaxing the premium tier prohibition of dual-class shares, bringing the UK into line with numerous other major stock exchanges around the world, such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the Nasdaq Stock Exchange (Nasdaq), Hong Kong, Singapore, Shanghai, India and Tokyo. Although, as the regulator of the Main Market, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) must conclude its consultation processFootnote 8 on associated changes to the Listing RulesFootnote 9 before the Review's proposals become effective, it does appear that the UK is inexorably on course to relax its rules on dual-class shares. In fact, reports suggest that a company issuing shares (an issuer) in a recent initial public offering (IPO) on the LSE Main Market's standard tier was informally notified prior to IPO that it was likely that dual-class shares will be permitted on the premium tier in the foreseeable future.Footnote 10 Whether or not the rules are relaxed after the FCA's consultation, dual-class shares will remain at the forefront of UK corporate governance debates for years to come. However, with the level of hostility to dual-class shares that exists amongst the UK institutional investor community, as evinced during the Call for Evidence phase,Footnote 11 any relaxation of the premium tier prohibition on dual-class shares will be accompanied by conditions designed to protect public shareholders from potential abuses of the structure and to appease institutional investors. Accordingly, unlike the US, where dual-class shares are permitted on the NYSE and Nasdaq with very few restrictions, the Review has proposed numerous conditions that it is hoped will maintain the high corporate governance standards of the premium tier.Footnote 12

Subjecting dual-class shares to restrictions resonates with the approach of several Asian exchanges such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, India and Shanghai. However, it is not axiomatic that subjecting dual-class shares structures to a package of public shareholder protection mechanisms will continue to support the growth and innovation that such structures are intended to achieve. This article commences by discussing the premium tier's approach to dual-class shares, following which the propensity for dual-class shares in general to satisfy the objectives of the Review will be presented. Using the conditions proposed by the Review as a launching point, this article will then critically assess the types of constraints commonly proposed to be placed upon the operation of dual-class shares structures. It will suggest that it is imperative that the design of constraints that protect public shareholders from potential abuses by controllers must also appreciate the freedom that founders seek through the adoption of dual-class shares to pursue their visions for their businesses. The article will conclude with a discourse on the challenges facing UK regulators in developing rules that balance the interests of public shareholders and founders, especially when confronted with a traditionally powerful body of UK institutional investors. However, unless that balance is maintained, climbing up the hill to relax the premium tier prohibition of dual-class shares to attract further listings will be nothing but a futile endeavour.

II. Dual-class Shares and the Premium Tier

Although dual-class shares had been previously permitted on the LSE's Main Market,Footnote 13 after an informal discouragement of new listings of dual-class shares in the 1960s,Footnote 14 in 2010, upon the delineation of the Main Market into premium and standard tiers, non-voting shares were formally prohibited from the premium tier,Footnote 15 followed by, in 2014, a de facto premium tier prohibition of classes of shares with voting rights disproportionate to their equity rights.Footnote 16 The premium tier was pitched as the most prestigious tier of the LSE, with the highest standards of corporate governance attached, and existing companies with dual-class shares structures were required to shift their inferior-voting shares from the premium tier.Footnote 17 Dual-class shares can, though, be listed in the UK on the standard tier and high-growth segment of the Main Market, and, outside of the Main Market, on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM), and the alternative trading platform, Acquis Stock Exchange (Acquis). Therefore, a brief exposition as to why the UK public markets do not already present a welcoming environment for founders wishing to adopt dual-class shares structures is felicitous.

AIM, Acquis and the Main Market's high-growth segment each cater for specific, albeit overlapping, audiences, with investor bases that reflect the types of issuers that float on those exchanges. AIM was established for small, growing companies, with less onerous listing requirements, and Acquis, with its main and growth markets, sits even below AIM with respect to the size of the companies it is attempting to attract. Although the Main Market's high-growth segment was established to attract companies too large for AIM, and, in particular, high-growth tech-companies, it is considered as only a market for mid-sized companies, not able to satisfy the free-float requirements of the premium and standard tiers,Footnote 18 and, as of the date of writing, only three companies have ever listed on the segment. When a company outgrows AIM, Acquis or the high-growth segment, it is likely to desire a graduation to the standard or premium tiers to access the broader base of investors therein, together with the resultant enhanced share price and liquidity. Therefore, even if the openness to dual-class shares of those lesser boards was successful in attracting the high-growth companies pursued by the UK,Footnote 19 the growth of such companies would be stunted unless they can “upgrade”, and, accordingly, the rules of the standard and premium tier become germane.

As above, dual-class shares are, though, permitted on the standard tier, which does envisage larger company listings. However, as of the time of writing, only three companies have undertaken listings on the standard tier with structures resembling anything like dual-class shares structures – in 2020, The Hut Group floated with the founder holding a single “special share” which, in effect, ascribes the right to block takeovers for a period of three years post IPO,Footnote 20 and, in 2021, Deliveroo and Wise listed with more traditional dual-class shares structures ingraining voting control in the hands of founders holding only a minority of the equity for a period of three and five years, respectively, post listing.Footnote 21 Even though the US has seen a surge in founders adopting dual-class shares on the listed markets,Footnote 22 to the extent dual-class shares can attract founders to list,Footnote 23 they have not been attracted in droves by the standard tier's openness to the structure. There are two main reasons. First, the “standard tier” suffers from an identity-crisis, with poorly defined objectives as to the issuers it is seeking to attract and with little to distinguish itself from the premium tier over-and-above permitting laxer listing standards.Footnote 24 Issuers and investors alike view the segment as being inferior to the premium tier.Footnote 25 The Hut Group, Wise and Deliveroo are unusual in representing large, high-profile, UK standard tier listings,Footnote 26 but the restriction to the standard tier (as a result of their capital structures) will have entailed compromises for the companies. For instance, The Hut Group delayed listing until it was sufficiently mature to attract an adequate level of investors and liquidity despite the diminished status of the standard tier,Footnote 27 and, in fact, after taking into account IPO pre-allocations (including to existing investors)Footnote 28 and private placements,Footnote 29 only around 25 per cent of the issued shares in the company became widely available to public shareholders; the existing pre-IPO shareholders retained a majority (and a significant majority of the fully diluted) share capital of the company. Wise, too, was a mature company at the time of listing,Footnote 30 and undertook a rare “direct listing” pursuant to which existing shares were admitted to trading but no new shares were offered to the public.Footnote 31 The company was therefore not in a position where it needed to attract new investors for equity growth financing.Footnote 32 Although Deliveroo listed as a younger company,Footnote 33 its business model had been significantly accelerated by the 2020 pandemic,Footnote 34 and, again, only a minority of shares were offered to the public, with 70 per cent retained by pre-IPO shareholders,Footnote 35 and 30 per cent of IPO shares allocated to three “anchor investors”.Footnote 36 Notably, speculation was rife that Deliveroo was using the standard tier as merely a staging-post until graduation to the premium tier became possible after the relaxation of its prohibition of dual-class shares.Footnote 37 Second, non-premium listed companies are ostracised from the FTSE UK Index Series (including, for example, the FTSE-100 and FTSE-350).Footnote 38 Ostracism from the indices is a key reason why the standard tier is considered unattractive,Footnote 39 since it excludes issuers from investment by passive investors with investment strategies that simply track specific indices,Footnote 40 and the corresponding increase in liquidity and share price.Footnote 41 Of further importance, given the UK Government's aspirations to “empower” retail investors and increase the opportunities for investors to share in the growth of companies,Footnote 42 is that many pension plans and other investment products pursue passive investment strategies, meaning that the capacity for the general public to participate in a diversified manner in the performance of dual-class companies is curtailed if they are restricted to the standard tier and omitted from the indices.Footnote 43 As an example, perversely, passive investors tracking the FTSE-100 are currently not able to invest, or share, in the burgeoning post-IPO share price of The Hut Group, even though it would otherwise sit comfortably within the FTSE-100 based upon market capitalisation.Footnote 44

Although the prospects of the standard tier might be improved if it were to be “re-branded” and if standard tier constituents were to become eligible for index-inclusion,Footnote 45 in relation to the former, it would take time to change perceptions, and, in relation to the latter, the decision would be in the hands of private index providers in consultation with their institutional investor clients.Footnote 46 Additionally, even if issuers were to become more open to the standard tier, they may seek to upgrade to the premium tier in the future. The strength of the UK public markets and its ability to attract high-growth companies are currently intrinsically linked to the admissions requirements of the premium tier. In the next part of this article, the manner in which dual-class shares in general can succeed in attracting those companies will be discussed.

III. Dual-class Shares to the Rescue

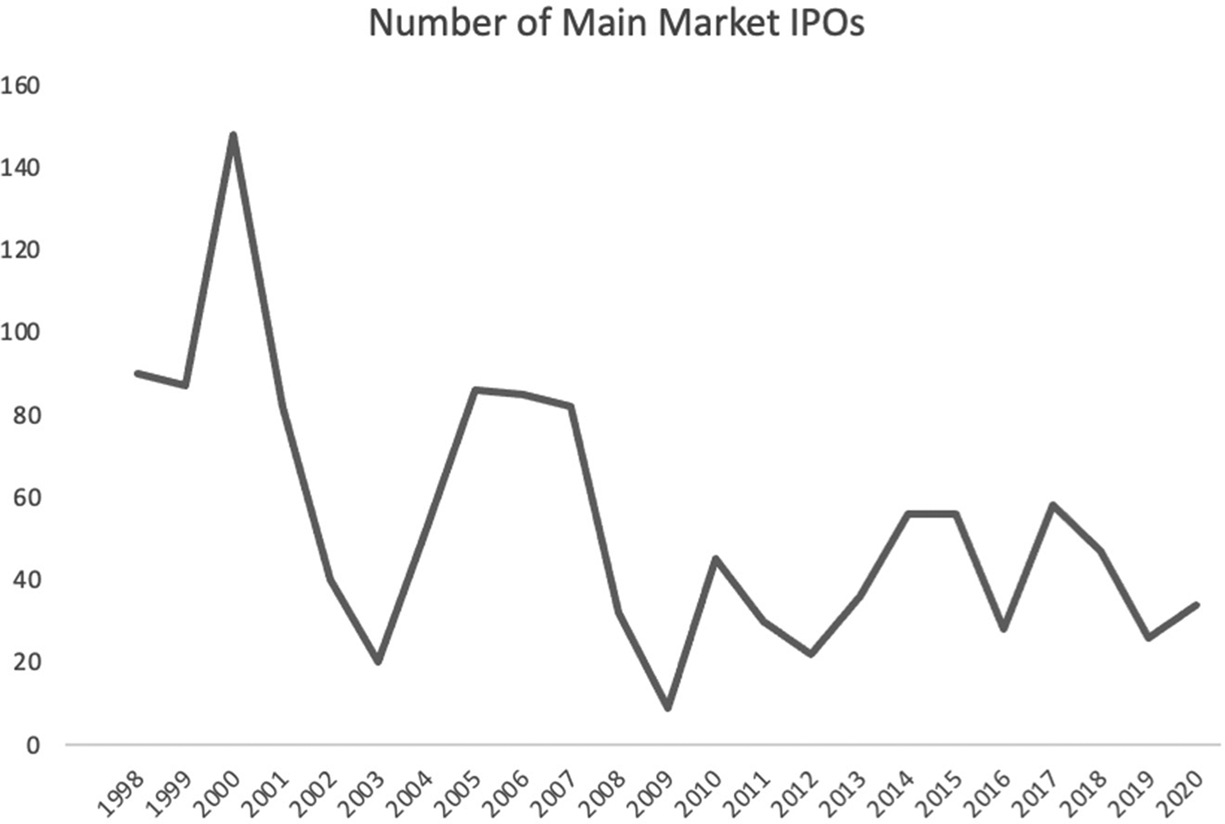

In acknowledging the important role that the public markets play in funding company growth and investment, and enabling investors to share in that growth, the Review noted the need to encourage the growth companies of the future to list in the UK.Footnote 47 However, recent experience suggests that the LSE's Main Market may not be cultivating an environment conducive to attracting those companies. The absolute number of companies on the Main Market fell by 57 per cent between 1999 and 2016.Footnote 48 Further data suggests a drastic fall of 40 per cent just between 2008 and 2020.Footnote 49 The decline does not simply stem from companies leaving the listed sector after public-to-private takeovers, but also ensues from a dearth of new listings. As shown in Figure 1, Main Market IPOs have been moribund in recent years, with annual numbers not recovering to those seen before the 2008 financial crisis. The decay in IPOs is in stark contrast to the rise in private, unlisted, businesses, which have increased in the UK by 72 per cent between 2000 and 2020.Footnote 50 Furthermore, the types of companies that do list on the Main Market are not evocative of the “new economy” that the UK is seeking to attract,Footnote 51 with companies from such industries only comprising 14 per cent of the market capitalisation of LSE IPOs between 2007 and 2017 – as compared to 60 per cent and 47 per cent on Nasdaq and the NYSE, respectively.Footnote 52

Figure 1 UK IPOs on the LSE's Main Market 1998–2020 (data derived from: London Stock Exchange, “Reports: Primary Markets, New Issues and IPOs”, available at https://www.londonstockexchange.com/reports?tab=new-issues-and-ipos&accordionId=0-838a7e19-eb32-49ba-a1b5-3e4eaea7021b).

Dual-class shares structures could encourage listings of innovative high-growth companies, especially in the new economy sectors of tech and life sciences.Footnote 53 A one share, one vote prescription on the premium tier is not appealing to such companies, due to the loss of control an IPO could entail for a founder of a large, innovative, high-growth company. A one share, one vote premium tier listing could, if the founder does not retain a majority of the votes in the company, result in the founder becoming exposed to the whims of the public markets, since, for a company incorporated in England and Wales, those with majority-voting control can remove directors from the board,Footnote 54 have a decisive influence on appointments to the board,Footnote 55 and determine the outcome of takeover offers.Footnote 56 Since the board determines the strategy of the company, and, almost ubiquitously, has the power to hire and fire the management team,Footnote 57 a founder may fear that early- or growth-phase investments in research and development and product-cycles, resulting in short-term share price declines, could lead to the founder being removed from the board by the public shareholders, or removed as an executive indirectly through the public shareholders’ influence over board decision-making owing to their control over board composition. Similarly, a decline in share price could expose the company to a predatory takeover bid, subsequent to which the management team is changed by the acquiror.Footnote 58 Such fears are especially pertinent in the realm of high-growth tech-companies where forthcoming innovative products may need to be kept confidential,Footnote 59 and where the correlation between medium-to-long-term investment and future benefit may not be easily observable to public shareholders,Footnote 60 who accordingly undervalue the company. After all, a corollary of the assumption that innovative companies have visionary foundersFootnote 61 is that those who are not so perspicacious cannot fully appreciate the founder's idiosyncratic vision.

A founder could preserve control by listing and retaining a majority of the shares in the company. However, in so doing, the founder will crystallise less of its investment in the company, and, since further shares issuances will dilute the founder's interest, will be constrained in the level of equity finance that can be raised at IPO and on an ongoing basis.Footnote 62 Dual-class shares, could, though, ride to the rescue. By creating classes of shares to which are attached differing levels of voting rights, but equal cash-flow rights, the founder can, by holding enhanced-voting shares and issuing inferior-voting shares to the public, engineer a scenario where it maintains majority-voting control while only retaining a minority of the cash-flow rights. Accordingly, the founder is able to sell a large portion of its investment in the company without losing control, and, by issuing inferior-voting shares, can also raise finance at IPO and post IPO while continuing to retain control.Footnote 63 With an unconstrained dual-class structure, with no restrictions as to when enhanced-voting rights can be exercised, the founder can guarantee his/her continued control and tenure as an executive, and takeovers of the company will not proceed without the founder's acquiescence. By assuaging the loss-of-control concerns of founders, dual-class shares can create a more welcoming premium tier ecosystem for tech-companies.

IV. The Need for Constraints

The preceding section of this article paints a pretty picture of dual-class shares. Read in isolation, one may therefore question why dual-class shares structures were ever prohibited from the premium tier in the first place. The reason can be summed-up in four words: “private benefits of control.” The concept pertains to the founder exercising its voting control to cause the company to take actions that are personally beneficial to the founder, but potentially detrimental to shareholder-value. A controller of a one share, one vote company, where the controller holds a majority of the shares, could also exercise its voting control in such a manner,Footnote 64 but, with dual-class shares, such behaviour is theoretically incentivised further, since the controller receives the full value of the extraction of the relevant private benefits, but only suffers from any commensurate fall in share price in proportion to a potentially disproportionately small equity ownership.Footnote 65 The extraction of private benefits can manifest itself in a variety of ways, from blatant extraction of the company's assets,Footnote 66 to more subtle extraction through the pursuit of projects which create financial,Footnote 67 or non-pecuniary,Footnote 68 benefits for the founder, but which are not optimal for shareholder wealth-maximisation. A detailed consideration of those actions, and, in contrast, the benefits that dual-class shares can bring to the UK public markets, is outside the scope of this article (and has been discussed in depth elsewhere),Footnote 69 since this article is primarily concerned with the conditions that may be attached to the acceptance of dual-class shares structures. However, by constraining the ability or scope of a founder to extract private benefits, the consequences of dual-class shares can be better shifted to positive, rather than negative, outcomes for public shareholders. Those constraints could encompass both measures that require enhanced-voting shares to be converted into inferior-voting shares upon events occurring which notionally increase the risks that pernicious private benefits will be extracted (so-called “sunset clauses”), and measures that reduce the incentives or scope for the extraction of private benefits ab initio. In the next section, the conditions that are commonly proposed to be attached to dual-class shares structures will be assessed, and it will be suggested that a balance must be preserved, protecting public shareholders on the one hand, and maintaining founder freedom on the other. Much like Goldilocks’ infamous, and perilous, sampling of porridge,Footnote 70 some conditions blow too hot, some too cold and some are just right.

V. Restrictions on the Exercise of Enhanced Votes

The one hand giveth, the other taketh away. Having empowered founders with disproportional voting rights, an obvious constraint would be to qualify the instances in which those enhanced-voting rights may be exercised. The most restrictive approach would be to limit the exercise of enhanced-voting rights to blocking takeovers. This is essentially the approach recommended by the Review,Footnote 71 which has suggested that a takeover bid is possibly the biggest threat to a founder's ability to bring its vision to fruition after IPO.Footnote 72 If takeovers can be blocked, though, an absence of the “market for corporate control” eliminates an important disciplining mechanism on management, since the management team will no longer be incentivised to perform diligently to protect their jobs from a decline in share price that opens-up the company to a takeover bid.Footnote 73 The underpinning of the restrictive approach is that by treating the enhanced-voting shares as one share, one vote on all other resolutions of the company, the public shareholders, assuming that they hold a majority of the equity, can still indirectly control the composition of the management team through their influence over the composition of the board,Footnote 74 thereby preserving an alternative disciplining mechanism. Ideologically, the restrictive approach may seem to be a happy medium that enables dual-class shares listings without prejudicing the rights of public shareholders if incumbent management is not performing adequately. However, such an approach can create difficulties for founders who seek to retain post-IPO control from three perspectives: board composition, public shareholder blocking rights and proactive public shareholder involvement.

First, founders are likely to covet control over the composition of the board as a whole, and in other jurisdictions, the decision to adopt dual-class shares will have been partly driven by a desire to retain that control. As discussed, the board will have control over the company's strategy, and will have the power to hire and fire managers.Footnote 75 Without control over the composition of the board, a founder cannot guarantee its continued tenure as, for example, chief executive officer (CEO) of the company.Footnote 76 The founder, realising its worst fears post IPO, has no assurances that public shareholders, using share price as a proxy for CEO performance,Footnote 77 will not cram the board with directors hostile to the founder's continuing role as CEO. Even the Review, which advocates the restrictive approach, acknowledges: “When founders bring their companies to market, they often seem to be concerned mostly about their vision not being derailed by being removed as a director/CEO.”Footnote 78 The divergence between the Review's acknowledgement and its approach will have been influenced by evidence that it is unusual for shareholders to remove directors from the boards of Main Market-listed companies.Footnote 79 However, shareholders do not have to assert their control directly, and the mere shadow of their powers can influence the behaviour of boards (and, therefore, management).Footnote 80 A CEO who ignores the demands of the public shareholders will be playing fast-and-loose with his/her continued employment, since boards can exert significant pressure on CEOs to resign, and being a listed company CEO is certainly not a “job-for-life”.Footnote 81 Even outside the domain of dismissal, the founder may encounter board opposition (influenced by the powers of public shareholders to remove board members) to its proposed actions or strategies, encumbering the ability of the founder to freely pursue its vision. Famously, the board of the US dual-class corporation, Facebook, was opposed to the founder's decision to acquire Instagram, an acquisition that the founder, overriding the board through his voting control over board composition, continued to pursue and which has created significant value for Facebook over the years.Footnote 82 It is exactly the pressure to genuflect to the short-term caprice of public shareholders that founders are seeking to avoid through the implementation of dual-class shares.Footnote 83

Second, the inability to exercise enhanced-voting rights on all shareholder resolutions will prospectively result in the public shareholders maintaining veto rights over all actions of the company which require shareholder approval. Several corporate actions require an ordinary resolution (majority vote),Footnote 84 or special resolution (voting approval of 75 per cent or more)Footnote 85 to be undertaken. Additionally, under the Listing Rules, certain actions require the pre-approval of shareholders holding premium listed shares.Footnote 86 The freedom that may be sought by founders in adopting dual-class shares could be appreciably curbed. For example, under Chapter 10 of the Listing Rules, shareholder pre-approval is required for large “Class 1” transactions.Footnote 87 Relevantly, an early-stage company, which has yet to generate substantive profits, may find that many potential acquisitions will result in it crossing the thresholds for shareholder pre-approval under Chapter 10.Footnote 88 Even though a visionary founder of an innovative, high-growth, founder-led tech-company may see significant long-term value and synergies in making large acquisitions, it will be time-consuming to obtain shareholder pre-approval, preventing the company from acting nimbly and alerting competitors to the possibility of an acquisition, and there is no guarantee that the public shareholders will share the founder's confidence that the relevant acquisition will eventually be successful. By way of example, if Deliveroo were to seek to graduate to the premium tier as reports have suggested,Footnote 89 and as a condition of such admission it was required to restrict the founder's exercise of enhanced-voting rights to takeover decisions, as a pre-profit company,Footnote 90 its ability to engage in acquisitions quickly and efficiently in what is a saturated industryFootnote 91 would be impeded by having to regularly seek shareholder pre-approval. Outside of substantial transactions, public shareholders could also create complications for a founder by not approving director remuneration policies pursuant to their binding voting powers,Footnote 92 or by eliciting bad publicity for the company, and the founder, by not approving remuneration actually paid to the founder under the relevant policy, pursuant to their advisory voting powers.Footnote 93 Public shareholders could use such votes to register discontent with the manner in which the company is being managed, or to impose pressure on the founder to take certain actions.Footnote 94 These are the types of public market pressures that deter founders from listing in the first place.

Third, public shareholders could proactively create disruption. Shareholders with sufficient votes can cause the company to call a shareholders’ general meeting to hear shareholder-proposed resolutions,Footnote 95 or can await the annual general meeting (AGM) and propose resolutions for the agenda.Footnote 96 In theory, those shareholders could instigate corporate actions, such as amendments to the articles of the company,Footnote 97 or even instruct the board to take certain actions.Footnote 98 In practice, it is unlikely that public shareholders will be able to corral sufficient votes to take those actions,Footnote 99 but one could see potential for public shareholders to undermine the founder's control. As with vetoes, activist shareholders could cause significant disruption by regularly requiring the calling of general meetings to exert pressure on the founder. Such agitations will be off-putting to a founder. A scenario could even be foreseen where, in the midst of a takeover offer that could otherwise be blocked by the founder, activists use shareholder-proposed resolutions to coerce the founder into accepting the offer, or even outside of a takeover offer, activists could use such tactics to compel the founder to voluntarily dismantle the dual-class structure in the hopes of putting the company “into play” and opportunistically soliciting a takeover.

The value of dual-class shares to founders above and beyond the ability to block takeovers can be elucidated from the US experience. Founders have other options to block takeovers in the US, including “blank-check preferred stock plans”, “poison pills” and charter supermajority requirements to approve mergers.Footnote 100 Founders, however, still appear to be adopting dual-class shares en masse.Footnote 101 This is the case even though the empirical evidence on dual-class shares is heavily skewed in the direction of discounted share prices after IPO as compared to similar one share, one vote companies.Footnote 102 Since such discounts do not correlate with decreased operating performance or shareholder returns, they represent public shareholders pricing-in the risk that their interests may be expropriated through the extraction of private benefits.Footnote 103 In contrast, the empirical evidence on the effect on share price of anti-takeover devices, generally, is more mixed.Footnote 104 It would appear that founders are willing to accept higher costs of capital to reap the benefits of being able to insulate all of the directors from public shareholder removal and control the shareholder voting process; dual-class shares are more valuable to founders than simple anti-takeover devices, and it appears that founders appreciate that nuance in practice as well as in theory.Footnote 105

If the principal reason for relaxing the premium tier's dual-class shares prohibition is to attract high-growth, new economy companies to the market, that aspiration will not be satisfied by taking an overly restrictive approach to the exercise of enhanced-voting rights. One may therefore suggest that the more permissive US approach,Footnote 106 where there are no mandated restrictions on how enhanced-voting rights may be exercised, should be adopted. However, giving a founder carte blanche to exercise enhanced-voting rights on all matters brings with it other pitfalls from a UK perspective. As discussed in more detail later in this article,Footnote 107 freshly introducing dual-class shares to the premium tier at this stage of the Main Market's evolution without at least a nod towards UK institutional investor concerns will be politically and diplomatically difficult. Also, even though investors seemingly price-in their risk at IPO,Footnote 108 the FCA will further be concerned about the ongoing consequences of dual-class shares rather than simply about pricing, since it has at its heart a mission to protect consumers, protect and enhance the integrity of the UK financial system, and promote competition.Footnote 109 Additionally, public shareholders in the UK do not benefit from the plethora of litigious tools available in the US – the US enjoys simpler ex-post tools to litigate against controlling shareholders after expropriation has taken place (which, in turn, can deter expropriation in the first place),Footnote 110 a more open litigious culture,Footnote 111 and more plaintiff-favourable civil procedure rules.Footnote 112 Furthermore, a competitive advantage could be gained if at least some ex-ante protective measures were adopted that place a ceiling on the types of expropriation that could occur – by assuaging public shareholder concerns to a degree, the cost of capital for UK dual-class companies could be reduced, as compared to the US where they are habitually discounted.Footnote 113 Therefore, a more granular approach with general scope for founders to exercise enhanced-voting rights, but with restrictions on specifically defined corporate actions, as adopted in a number of other jurisdictions, such as Hong Kong,Footnote 114 Singapore,Footnote 115 IndiaFootnote 116 and Shanghai,Footnote 117 could better balance the control sought by founders and protection of public shareholders. The restricted corporate actions must be chosen carefully, though, since the founder must be able to operate the company on a day-to-day basis unhindered by public market pressure, but should not be able to egregiously and opportunistically take actions that expropriate value from public shareholders. Limiting the capacity of a founder to cause a company to engage in large transactions can severely encumber the business strategy of a high-growth company.Footnote 118 However, placing restrictions on the founder's ability to, for example, amend the articles of the company, voluntarily wind-up the company, reduce capital, disapply pre-emption rights, appoint auditors, or engage in related-party transactionsFootnote 119 limits the opportunities for abusive behaviour without undermining the founder's pursuit of its vision.

A wholesale adoption of the approach of those Asian exchanges, though, will not be appropriate in a UK context. All four of those exchanges require all shares to be treated on a one share, one vote basis on resolutions to appoint and remove independent directors.Footnote 120 Although independent directors could play an important role in monitoring the actions of controlling shareholdersFootnote 121 and relating public shareholder concerns to the board, if public shareholders could nominate and appoint their chosen representatives, it could have the inadvertent incentive on a founder not to comply with the UK Corporate Governance Code recommendations that at least half the board, not including the chair, be independent non-executive directorsFootnote 122 and that the chair be independent upon appointment.Footnote 123 In a contentious scenario, a board in compliance could quickly become comprised of a majority of directors appointed by, and loyal to, the public shareholders, thus jeopardising the ability of the founder to manage the company insulated from public shareholder pressure. As discussed, a founder adopting dual-class shares will desire to control the composition of a majority of the board. Public shareholders could, though, be given the right to nominate and appoint a minimum number of, although not all, independent directors or have veto rights over independent directors nominated by the founder.Footnote 124 Another feature of the Asian exchanges is the manner in which the restriction is implemented: on specific corporate actions, all shares are treated as one share, one vote. However, in the UK, such a mechanism could allow the public shareholders, if they hold sufficient equity, to unilaterally cause the company to take those actions.Footnote 125 Instead, a better mechanism would be a dual-vote system, pursuant to which two voting approvals are required to effect the relevant corporate action: a vote where enhanced-voting rights are respected, and a second vote where all shares are treated on a one share, one vote basis. In that way, the holders of a majority of the equity will possess a veto right over specified corporate actions (which could potentially be used to harm their interests), but cannot unilaterally cause the company to take those actions. Although a founder of a dual-class shares company holding a majority of the equity would be able to effect the relevant actions on his/her own, the company would be in no worse a position than if it had a one share, one vote controlling shareholder.

The Asian approach to corporate actions, as modified above, strikes an equilibrium between founder latitude and public shareholder protection. Regulators who fear the motives of a founder in taking management decisions should, as discussed later in this article, look to other tools to align founder actions with shareholder-value.Footnote 126

VI. Time-dependent Sunset Clauses

Another condition that could be attached to dual-class shares structures is a “time-dependent sunset clause”, a concept that has been floated for many years.Footnote 127 Regulation could require that the articles of any dual-class issuer include provisions that automatically convert enhanced-voting shares into one share, one vote shares after a specific time period post IPO. The rationale is that the company only requires dual-class shares in the early post-IPO years (when asymmetric information issues may subsist between public shareholders and the founderFootnote 128) to allow the founder to pursue its long-term vision without fear of removal or a takeover if short-term profits are non-existent or minimal. However, as the business matures, with product-cycles becoming more obvious, and business strategy becoming clearly evident, the need for dual-class shares erodes, and the risk increases that dual-class structure is being maintained merely to extract pernicious private benefits.Footnote 129

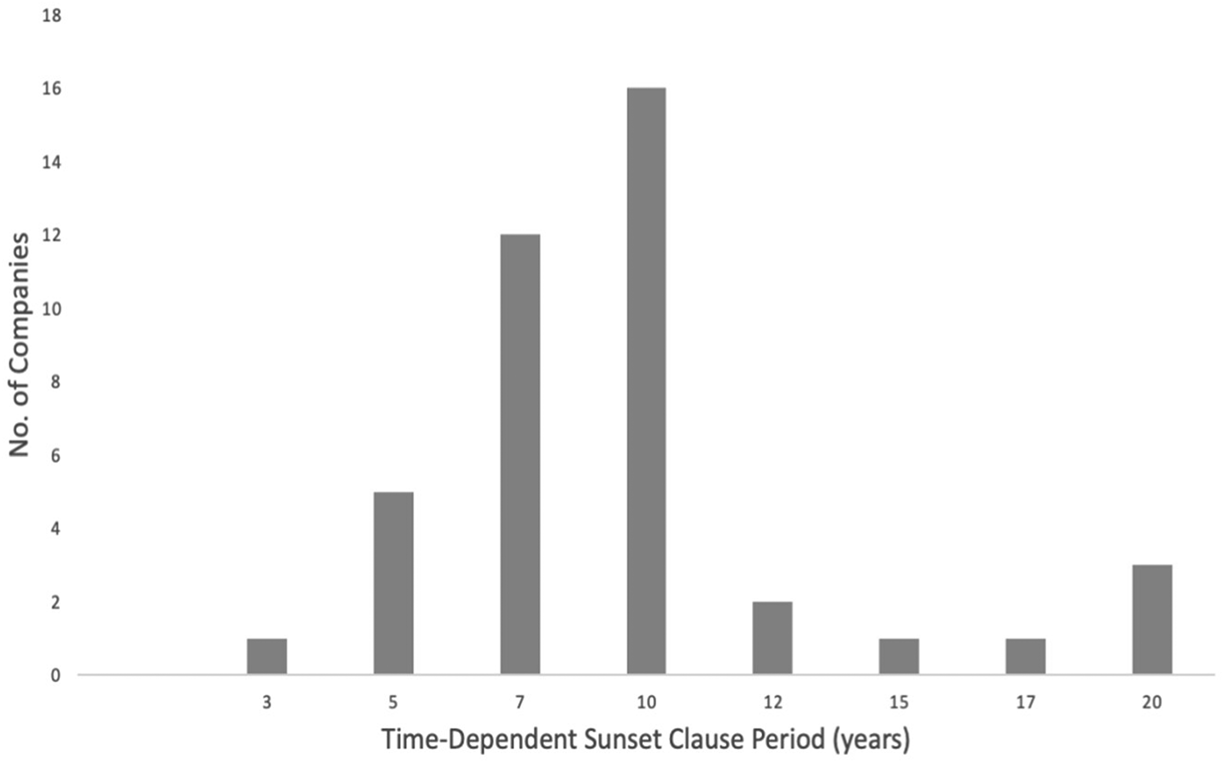

The challenge with mandated time-dependent sunset clauses is in ascertaining the optimum time period on a one-size-fits-all basis. Although some empirical evidence suggests that the benefits of dual-class shares fade as companies become older,Footnote 130 there is no clear bright-line period after which the structure becomes costly to public shareholders. In the US, where time-dependent sunset clauses are not mandated, a handful of dual-class issuers have voluntarily adopted such provisions.Footnote 131 Predictably, though, as shown in Figure 2, the time periods adopted for such provisions vary considerably.Footnote 132 Even other stakeholders are uncertain of the optimal period. Regulators in India mandate,Footnote 133 and the Review proposes,Footnote 134 a five-year period, yet the Council of Institutional Investors, a representative body for US institutional investors publicly antagonistic to dual-class shares,Footnote 135 recommends a longer period of seven years.Footnote 136 Such divergences are unsurprising, since the optimal period will vary on a company-by-company basis, underpinned by a variety of factors, including the maturity of the company at IPO, the length of product-cycles and the nature of the business.Footnote 137 An even more esoteric consideration will be the bearing that the time horizon and age of the founder has on the length of the innovative growth phase of the company. It is not feasible to predict at the time of an IPO the exact point in time when the motivations of a controller will diverge from the interests of the public shareholders,Footnote 138 and any mandated sunset clause, such as the Review's proposed five-year period, will be completely arbitrary in nature.Footnote 139 An obvious consequence is that dual-class structure could be defenestrated too soon, before the founder has had the opportunity to implement its vision or resolve the asymmetric information issues between it and the market as a result of challenges in project observability.Footnote 140 Public shareholders could be given the opportunity to extend the sunset period prior to its expiry,Footnote 141 but institutional investors, who are traditionally sceptical of dual-class shares, are likely to be opposed to any extension: the very short-term pressures and project unobservability consequences from which founders are insulating themselves through dual-class shares structures will influence the voting of shareholders on the extension.Footnote 142 Even if public shareholders were inclined to consider an extension of the structure, to increase the chances of the extension, the founder may find it necessary to cause the company to take actions that are more easily observable to the public shareholders,Footnote 143 and, therefore, to forego the more uncertain, innovative projects that dual-class shares structures are intended to encourage.Footnote 144 The success of US dual-class corporations such as Facebook, Alphabet and Regeneron which have continued to innovate and create value for public shareholders many years after IPO,Footnote 145 could have been curtailed if they had implemented short time-dependent sunset clauses, with or without the option for public shareholders to extend, since it would have required them to shape their business strategies and product-cycles to short-term fluctuations in share price.

Figure 2 US dual-class shares IPOs adopting time-dependent sunset clauses as of 31 December 2020 (data derived from: CII, “Companies with Time-based Sunset Approaches to Dual-class Stock”, available at https://www.cii.org/files/2-13-19 Time-based Sunsets.pdf; CII, “Dual-class IPO Snapshot 2017–2020 Statistics”, available at https://www.cii.org/files/2020%20IPO%20Update%20Graphs%20.pdf).

Even if the optimal time period could be discerned, although quixotically persuasive, mandatory time-dependent sunset clauses could have a chilling effect on an exchange seeking to attract swathes of innovative companies. Founders of truly innovative companies may be reluctant to list in the knowledge that an IPO only grants them a finite period of control within which to pursue their idiosyncratic visions.Footnote 146 Furthermore, an exchange mandating time-dependent sunset clauses will suffer from a competitive disadvantage against the NYSE, Nasdaq, Hong Kong, Singapore, TokyoFootnote 147 and Shanghai, with India being the only dual-class shares jurisdiction that also mandates such a sunset.Footnote 148 Moreover, as is notable in the context of the UK's aim to attract innovative companies to the LSE at earlier stages of their life-cycles,Footnote 149 even if a dual-class issuer were inclined to accept a time-dependent sunset, it is likely that its IPO would be delayed until the founder could be certain that the relevant time period would be a sufficient period of control. Although The Hut Group and Deliveroo both employed time-dependent sunsets of three years, it is questionable whether these companies are truly the innovative tech-start-ups desired. The Hut Group had been promoted as a tech-listing, but some commentators described the company as a retail enterprise, with “tech” only forming a minority of the company's business.Footnote 150 It would also be a stretch to describe Deliveroo as operating in an innovative industry, with the online food delivery segment having become extremely saturated,Footnote 151 and industry innovation being largely driven outside the delivery service field.Footnote 152 The founders and CEOs of The Hut Group and Deliveroo are businessmen rather than the visionary tech-founders of Facebook, Alphabet, Snap, Zoom and many other US dual-class tech-corporations. The Hut Group is also a mature company, listing 16 years after being founded, with venture capital investors, rather than public shareholders, being the beneficiaries of the huge returns during the high-growth phase of the company.Footnote 153 Although Deliveroo listed eight years after foundation, the founder acknowledged that the 2020 global pandemic had accelerated customer take-up of food delivery services by at least three years,Footnote 154 and, after much antitrust regulatory scrutiny regarding a 2020 investment by Amazon,Footnote 155 it may be that an IPO in a market where the brand is known (and where the company operates in a consumer-facing sector currently divided along continental linesFootnote 156) was the only realistic option for the company and investors. Concerningly, with the imposition of time-dependent sunset clauses potentially deterring numerous early-stage, high-growth innovative companies, a market could develop where it is mainly mature companies, and companies that are less redolent of the “new economy” aspirations of the Review, adopting dual-class shares, for which dual-class shares structure in fact provides little in the way of benefits, and where pernicious private benefit extraction is more likely to overshadow the upsides.Footnote 157

A one-size-fits-all time-dependent sunset clause is a blunt tool. In fact, it is not time per se that causes a change in the dynamics of the company – time is merely a proxy for events that could occur over time that result in greater likelihood of private benefit extraction and/or lesser necessity for dual-class shares.Footnote 158 For example, transfers of enhanced-voting shares to a new controller, a new board changing the strategic direction of the company, or simply the skills or interest of the founder waning could all undermine the need for, and benefits of, dual-class shares or result in greater levels of private benefit extraction.Footnote 159 Rather than imposing an arbitrary time period which could deter founders, a more targeted approach would be more effective, under which dual-class shares structure is converted into one share, one vote upon specific events taking place. It is simple to tailor provisions to certain events: as below, sunset clauses could be triggered by transfers of enhanced-voting shares or cessation of a founder's influence on the company's strategy.Footnote 160 The occurrence of other events, such as when the founder's skills begin to wane, are more ethereal and may be impossible to define accurately. In those cases, though, the approach should be to ensure that the incentives on the founder to take actions that are costly to public shareholders or to voluntarily continue with a costly dual-class structure are moderated. A solution would be to ensure that the founder has sufficient “skin-in-the-game”, to which this article turns next.

VII. Maximum Voting Ratios

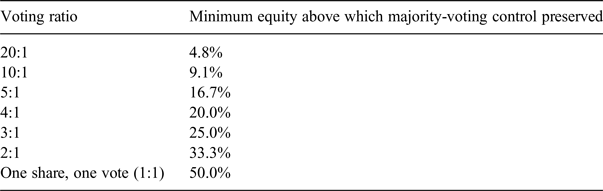

Maximum voting ratios operate by placing a cap on the ratio of voting rights attached to an enhanced-voting share to voting rights attached to an inferior-voting share. For example, Hong Kong,Footnote 161 Singapore,Footnote 162 ShanghaiFootnote 163 and IndiaFootnote 164 mandate maximum voting ratios of 10:1, and the Review proposes a 20:1 ratio for the premium tier.Footnote 165 Classically, voting ratios have two roles. First, a maximum voting ratio ensures that the public shareholders have at least a de minimis level of votes. A maximum voting ratio could ensure that public shareholders hold sufficient votes to propose shareholders’ resolutions.Footnote 166 Of course, if the exercise of enhanced-voting rights is already restricted to, for example, the blocking of takeovers,Footnote 167 all shareholders would be treated on a pari passu basis on all other votes no matter the voting ratio, in which case, the second role is more apropos – a maximum voting ratio essentially requires a controller to maintain a minimum level of skin-in-the-game, capping its incentives to extract private benefits, which rise at an increasing rate as the controller's equity interest declines.Footnote 168 For instance, with a voting ratio of 20:1, a dual-class founder seeking to establish majority-voting control would need to hold at least approximately 4.8 per cent of the company's equity. Table 1 sets out the minimum level of equity that a controller must hold to maintain majority-voting control at different maximum voting ratios.

Table 1: Minimum equity above which majority-voting control can be preserved as a factor of enhanced-voting share:inferior-voting share voting ratio

Determining the appropriate one-size-fits-all voting ratio, though, is as challenging as determining the optimal time-dependent sunset period. The market capitalisation of the company will be relevant: 4.8 per cent of the equity is obviously much more skin-in-the-game where market capitalisation is £5 billion compared to just £50 million.Footnote 169 Market capitalisation could also vary over time, through share price fluctuations and further finance-raising equity issuances. Additionally, a further consideration is personal net-wealth, with a given voting ratio having different bearings on the behaviour of a founder depending upon the gains he/she has made at or pre IPO. Other business interests of the founder may also be pertinent.

Therefore, a progressive avenue would be to instil flexibility. The FCA could mirror its approach to the free-float rules, by imposing a default requirement that could be waived or revised on a case-by-case basis.Footnote 170 Furthermore, rather than implementation by way of voting ratio, consideration should be given to, instead, requiring a founder to retain a specific number of equity shares based upon a percentage of the issued shares as of the date of IPO (as adjusted on a continuing basis for future non-cash share splits, bonus shares and reorganisations). If the founder disposes of sufficient shares to drop below the relevant threshold, its enhanced-voting shares would convert into one share, one vote. Such a “divestment sunset” presents advantages over maximum voting ratios, since a voting ratio could create the perverse post-IPO disincentive on the founder to issue further equity for finance since, if the founder already owns the minimum level of equity to retain majority-voting control, it would have to subscribe to further equity shares in the issuance to maintain that majority-voting control. Since the relevant threshold could be lowered by the FCA in its discretion, and, with a divestment sunset, it will not organically increase the amount of equity required to be held with escalating market capitalisation over time, the default can be set relatively high. The default should represent a legitimate level of skin-in-the-game, but not be so high that it prevents a founder from crystallising significant wealth on IPO and leading to issuers dismissing a premium listing out of hand. It is difficult to contend, though, that 4.8 per cent,Footnote 171 for example, is generally a sufficient level of skin-in-the-game to substantively disincentivise a controller from extracting substantial private benefits, other than possibly with the largest of listings. It is likely that such a founder will have garnered sizable riches by substantially exiting its investment in the company at IPO, and, consequently, 4.8 per cent will not represent a meaningful constraint on the controller. The situation is exacerbated if, owing to the dispersed nature of the remainder of the shares held by public shareholders,Footnote 172 the founder can maintain “effective control” with less than, and in some cases, substantially less than, a majority of the votes in the company.Footnote 173

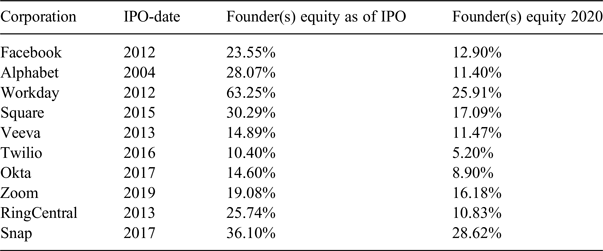

The default level for the premium tier should be carefully considered, but it could be set higher than that of the Asian exchangesFootnote 174 and still remain competitive. Unlike with the divestment sunset described, a founder listing on the Asian exchanges must continue to participate in fresh share issuances in order to retain majority-voting control while holding the minimum level of equity. Such a requirement can be consequential for high-growth tech-companies where acquisitions financed through the issuance of shares (either to the sellers as consideration or to the market to generate cash) can be essential for growth. Although a founder wishing to create an extreme divergence between voting and cash-flow rights may be attracted to the US, where no minimum equity retention requirements are regulatorily imposed, in practice, it seems that founders do not regularly seek to extravagantly depress their equity interests. Table 2 summarises hand-collected founder equity ownership information for the 10 largest (by market capitalisation) founder-led dual-class corporations that listed in the US after 2000, as at IPO and as of 2020. Most of those corporations listed with the founders holding at least 15 per cent of the equity, and, in many cases, far more. Although, post IPO, many of those founders have reduced their equity ownership percentages, those figures include dilution from post-IPO equity issuances, which would not be taken into account when applying a divestment sunset (as opposed to a maximum voting ratio). Further research in this area would be welcome, but, based upon more recent large US dual-class IPOs, a default level of around 15 per cent, which under the proposals in this article could, in any case, be relaxed in the discretion of the FCA, would appear to satisfy the balance between attracting issuers and protecting public shareholders. Taking the two most enduring corporations in Table 2 (Facebook and Alphabet) as of 2020, those corporations had been listed for eight and 16 years, respectively, and the founders owned approximately 13 and 11.5 per cent of the equity, respectively. Both corporations, though, have issued substantial levels of shares post IPO for financing and acquisition purposes, and, therefore, in the context of a divestment sunset (a limited form of which has been implemented by AlphabetFootnote 175), the founders would still hold well above 15 per cent of the IPO-date outstanding shares.Footnote 176

Table 2: Founder(s) equity ownership for the top 10 (by way of market capitalisation) US dual-class corporations with post-2000 IPO dates (data hand-collected from the Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC's) “Edgar website” – 2020 equity ownership was derived from the most recent public filings as of 17 September 2020; market capitalisation rankings determined as of 17 September 2020 from the constituents of the MSCI USA Index, available at https://www.msci.com/constituents)

A handful of dual-class founders shown in Table 2 have clearly substantially reduced their equity holdings in a much shorter period than Facebook and Alphabet through divesting of shares rather than dilution – however, they are in the minority, and the premium tier should not be so welcoming to companies that intend to implement such excessive divergences between voting and cash-flow rights. An appropriate level of skin-in-the-game is potentially the most crucial form of public shareholder protection for dual-class companies. For example, a founder whose interest has waned will be more open to stepping-down from management and handing the reigns to a fresh management team that will increase shareholder-value if that founder has more than a negligible level of wealth still tied up in the company.Footnote 177 Equally, the founder may even be willing to collapse the dual-class structure voluntarily if it will create an uplift in share value at a time when the need for dual-class shares has eroded.Footnote 178 A divestment sunset will mitigate insidious behaviour ab initio, and, since the divestment of equity post IPO is in the hands of the founder, will be more attractive to founders than the cliff-edge of an arbitrary time-dependent sunset.

VIII. Transfer-linked and Director-linked Sunset Clauses

Two common conditions attached to dual-class shares structures, and also proposed by the Review for the premium tier,Footnote 179 are restrictions on the capacity to hold and transfer enhanced-voting shares. Essentially, these are event-driven, more specifically, “transfer-driven” and “director-linked”, sunset clauses, since enhanced-voting shares automatically convert into one share, one vote upon a restricted transfer, or upon the holder ceasing to be a director. Hong Kong,Footnote 180 Singapore,Footnote 181 Tokyo,Footnote 182 IndiaFootnote 183 and ShanghaiFootnote 184 have all mandated transfer-driven sunset clauses, and, even in the US, it is not uncommon for transfer-driven sunsets to be voluntarily adopted.Footnote 185 Director-linked sunset clauses are also mandated in Hong Kong,Footnote 186 SingaporeFootnote 187 and Shanghai,Footnote 188 and, in the US, the voluntary uptake of related death or incapacity sunsets has become more common in recent years.Footnote 189

A transfer-driven sunset can be easily espoused. Institutional investors readily, albeit perhaps reluctantly, invest in dual-class shares structures.Footnote 190 However, heavily factored into any investment decision is their faith in the enhanced-voting shareholder. This is particularly pertinent where the exercise of enhanced-voting rights is unrestricted and the founder is entrenched as CEO. Institutional investors will be overtly backing the founder's talent and vision for the company,Footnote 191 and pricing the securities accordingly. As the Review states: “Their vision and their ability to execute that vision is often part of the company's selling point.”Footnote 192 If a fundamental motive for dual-class shares is to give founders a transition period during which they can pursue their visions insulated from the public shareholders, its justification falls away upon transfers of voting control to other persons. Exceptions to the transfer-driven sunset could be permitted, so long as they do not run a cart and horses through the protective measure. Exceptions for transfers for estate planning or charitable purposes, provided that the transferor continues to have control over voting decisions of the transferee, would be acceptable.Footnote 193 In contrast, wide exceptions to allow unencumbered transfers to family members, as preserved by Deliveroo for example,Footnote 194 are less easily justifiable.Footnote 195 Although a founder may believe that a family member can continue his/her legacy, research has shown that company performance deteriorates when family members assume management from founders.Footnote 196

A director-linked sunset ensures that the enhanced-voting shareholder is engaged in the running of the company,Footnote 197 and further reflects the contention above that investors are buying shares based upon their faith in the founder's vision. If the founder is no longer driving the strategy of the company, the validation for retaining disproportionate control crumbles. From a UK perspective, a director-linked sunset also has another positive consequential effect by subjecting any founder holding enhanced-voting shares to the directors’ duties regime.Footnote 198 Although practical and legal impediments can moderate the capacity of those duties to deter misconduct or mismanagement,Footnote 199 at least a baseline level of accountability will exist against which the founder's actions can be gauged.

Of course, the founder being a director is not a surety that the founder will play an integral role in guiding the company's strategy. If the founder is not also intrinsically involved in day-to-day management, his/her non-executive directorship could represent no more than a bauble on a Christmas tree, as was once infamously remarked.Footnote 200 Tokyo and India have tacitly accepted this subtlety by taking a stricter approach which requires, in most circumstances, that the enhanced-voting shareholder remains as an executive manager.Footnote 201 However, from a practical perspective, it is challenging (to say the least) to draft regulatory rules which adequately define an executive employment role of sufficient seniority and genuine in substance as well as form. A founder with control over the composition of the board could easily “game” the system. Such a “manager-linked” (as opposed to director-linked) sunset could create unintended consequences, and result in a founder CEO “hanging-on” too long past his/her expiry date. If a management-linked sunset clause had been in operation at Alphabet, where the founders remain on the board but have stepped away from their CEO and President roles,Footnote 202 they might not have been so enthusiastic to usher in a fresh CEO as they would have also lost control of their company. Although in an ideal world manager-linked sunsets are commended, from a practical perspective, mandated director-linked sunsets would be more effective on the premium tier.

The adoption of transfer-driven and director-linked sunset clauses would be a cogent approach for the premium tier to take. They respect the balance between ensuring that investors get what they have bargained for and ensuring that a founder can pursue his/her personal vision for the business. They strike at the heart of events that could occur which undermine the legitimacy of dual-class shares structures,Footnote 203 and collapse the structure into one share, one vote with surgical precision, making the blunt trauma of a time-dependent sunset clause all the more jarring.

IX. The “Policy Minefield”

In this article, in the context of the UK's premium tier finally entertaining the possibility of dual-class shares, the most common varieties of investor protections have been canvassed. A common thread is the importance of providing credible comfort for public shareholders that their interests will not be egregiously expropriated, without undermining the very reasons that a founder may seek the succour of dual-class shares structure in the first place. The dual-class shares path that the UK takes over the coming years will characterise the trajectory of the LSE for decades to come, and it is vital that the regulators appropriately weigh the competing tensions. However, that regulatory path is mired in peril. UK regulators must contend with highly influential UK institutional investors who are traditionally opposed to any initiatives that dilute shareholder rights,Footnote 204 and have, in the past, denounced dual-class shares. UK institutional investors focus on the costs of dual-class shares structures created by an attenuation of their powers to influence the management of companies and discipline self-serving managers. Although the ability of such managers to exploit their control by siphoning assets from the company or engaging in conflicted transactions should be substantively restrained by strong UK anti-fraud rules, audit requirements, financial press, and, on the premium tier, related-party transaction regulations,Footnote 205 institutional investors will still be concerned that founder control could manifest itself in the company taking actions primarily in the interests of the founder rather than shareholder wealth-maximisation,Footnote 206 or the entrenchment of a management team unsuited to leading the company.Footnote 207 Those concerns will reverberate with the UK regulators, since, historically, the UK regulators have been heavily influenced by the views of UK (particularly “long-only”) institutional investors, who have often engaged in extensive collaborative lobbying and have regularly played a significant role in the development of market regulations.Footnote 208 That direct influence harks back to an era when UK pension funds and insurance companies were the dominant players on the UK equity markets.Footnote 209 The views of UK institutional investors on dual-class shares and the influence they can exert will have led to the Review taking a half-hearted premium tier approach to dual-class shares and adopting a suite of constraints which, as discussed in this article, are likely to deter the very founders the Review is seeking to attract.

One may query, though, why institutional investors should take such a conservative position on shareholder rights in the context of dual-class shares when the empirical evidence does not show that dual-class companies perform worse, from the perspective of operating performance and buy-and-hold returns, than one share, one vote companies,Footnote 210 and where concerns that they could be lumbered with a self-serving dual-class shares controller or an underperforming management team can be mitigated through the judicious use of transfer-driven sunset clauses and ensuring that the controller has sufficient skin-in-the-game. Their position, though, betrays underlying tenets, with UK institutional investor views on dual-class shares being a microcosm of their resistance to reform of the equity markets generally. The importance UK institutional investors attach to maintaining shareholder rights will partly stem from them coveting their perceived dominion over company boards that coerces those boards into continuously heeding share price, and, relatedly, a desire to preserve their position as the dominant influence on UK corporate governance policy. They will fear that the influence over the regulators that they have enjoyed for decades will diminish if their power to exert influence over corporate actions in the listed markets is also moderated. By way of comparison, institutional investors have not enjoyed quite such a historic dominance over corporate managers in the US, and when the NYSE was considering the relaxation of its erstwhile prohibition of dual-class shares structures in the late 1980s and early 1990s, institutional investors did not dominate the market to the same extent as the UK during that period,Footnote 211 leading to the broadly permissive dual-class shares rules now apparent on the NYSE. Additionally, UK institutional investors are becoming more global themselves,Footnote 212 and reforms designed to attract contemporary, high-growth, new economy IPOs on the LSE will not be a priority for those investors when they can maintain exposure to such companies through investments on foreign exchanges and even, in some cases, in private equity funds.

Similarly, one may also query why the UK regulators kowtow to the views of UK institutional investors when the traditionally influential cabal of UK pension funds and insurance companies that once dominated the market now only form a very small part of the equity markets in the UK.Footnote 213 The market is currently dominated by foreign institutions which, despite their public opposition, have, in practice, been open to investing in dual-class shares structures.Footnote 214 There are three main reasons for the outsized influence of UK institutional investors on UK capital markets policy. First, since the Cadbury Report of 1992,Footnote 215 shareholders have been given a central role in policing the corporate governance of listed companies. The UK CGC operates by prompting corporate disclosure so that informed shareholders can instigate changes in those companies if necessary, and recent regulatory measures have emphasised a desire for greater stewardship engagement by (especially UK) institutional investors with the management of companies in which they invest.Footnote 216 Giving founders greater scope to insulate themselves from public shareholders through the adoption of dual-class shares will hamper those regulatory efforts, and, equally, institutional investors will be concerned as to how they will be able to satisfy regulatory fiat for them to engage with investee companies more effectively if they do not possess the tools to ensure that their voices are heard.Footnote 217 Second, preserving regulatory and governance exceptionalism has contributed to the LSE achieving disproportionately lofty prominence and scale.Footnote 218 Developing a reputation for the highest standards of corporate governance and preservation of investor rights created a burgeoning market to which investors were attracted. The natural tendency is to continue with such an approach on the assumption that it will continue to reap similar rewards. Third, the very nature of the LSE's regulator, the FCA (which has, in one guise or another, had responsibility for the Listing Rules since 2000), can foster a conservative approach to reform. As an independent public body with a statutory foundation and a mission to protect consumers, prevent anti-competitive behaviour and protect the integrity of the UK's financial system,Footnote 219 the FCA is more likely to prioritise protecting against downside risk to public shareholders,Footnote 220 which will exacerbate its inclination to support the views of UK institutional investors, rather than support companies seeking to innovate, risk-take and disrupt.

However, it is surely time for a change in approach. It is natural for a national regulator to consider seriously the stances of domestic financial institutions, but when investors are becoming increasingly more global, regulators should also consider whether prioritising the views of investors forming a minority of the market is in the best long-term interests of the exchange or the wider economy. Taking stewardship first – although with dual-class shares the effectiveness of stewardship engagement by institutional investors with company management will be tempered, even with one share, one vote companies, several structural, legal and commercial pressures exist that discourage institutional investors (especially passive investors that are increasingly forming a larger part of the marketFootnote 221) from engaging with corporate management on a company-by-company basis.Footnote 222 There has been significant scepticism that UK institutional investors do in fact engage effectively with one share, one vote companies,Footnote 223 and the regulators have begun to embrace a wider notion of stewardship moving beyond individual company engagement to stewarding systemic market-wide risks.Footnote 224 Given that there is sparse evidence that effective and widespread issuer-specific engagement is taking place even in one share, one vote companies, the ideal of stewardship should not be a decisive reason to overly constrain the use of dual-class shares structures. In relation to the desire to preserve the exceptionalism of the premium tier, it should be acknowledged that the shareholder rights governance mechanics that have been ingrained into the premium tier are reminiscent of an exchange built upon retail, manufacturing, financial and natural resource issuers. In an era where new economy companies, the businesses of which are not as simple to assess or observe as the previous “old economy” companies, are becoming more pervasive, an ideological focus on public shareholder rights could hinder rather than support the continued success of the LSE. Furthermore, the LSE is arguably facing greater competition from foreign exchanges than at any other time in its history. Whereas prior to leaving the EU, the UK could exert influence over EU regulations to drag the regulatory approaches of the exchanges of other Member States closer and closer to those of the premium tier, now the LSE is in more open competition with those exchanges. Although a “race-to-the-bottom” in terms of corporate governance would not be in the long-term interests of any economy, there needs to be a greater acknowledgement that the LSE is falling behind other exchanges when it comes to attracting new economy companies to IPO. Therefore, although investors should be protected from egregious exploitation, it may be time to appreciate that a compromise is necessary that sacrifices ideologically optimal shareholder rights in favour of a pragmatic regime that balances investor protection against encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship. Deliveroo and Wise are cases in point. The companies listed on the standard tier after the Review's publication, and implemented “genuine” dual-class shares structures that gave them more flexibility than the Review's proposals for the premium tier, notwithstanding, in the case of Deliveroo, the company's possible intention to upgrade to the premium tier in the future. It would appear that the concerns in this article that the Review's proposals on dual-class shares do not cater for the needs of founders have a real-world basis. Exceptionalism may preserve the prestige of the premium tier, but “at what cost”? As the Review itself points out, “it makes no sense to have a theoretically perfect listing regime if in practice users increasingly choose other venues”.Footnote 225

Ultimately, though, the underlying purpose of the FCA, as the LSE's regulator, may need to be reviewed. As discussed above, in its current form, it is always more likely to prioritise protection against downside risk over promoting upside potential. By way of contrast, the NYSE, although under the oversight of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), has, unlike the LSE, prima facie responsibility for its own listing rules,, which gives it greater scope to consider its commercial interests in attracting further issuers.Footnote 226 This author certainly does not advocate for the UK to take a completely ruthless approach to attracting issuers to the equity markets while throwing public shareholder rights under the bus. However, as iterated throughout, it is all about balance. Interestingly, Hong Kong and Singapore, as described in this article, have developed what could be considered to be fairly pragmatic positions on dual-class shares that venerate public shareholder rights, while recognising the twenty-first century aspirations of tech-company founders. It is no surprise that the Hong Kong and Singapore regulators wear two hats: as listed companies in their own rights (requiring them to consider their own competitive interests) and as regulators of the markets (under statute in the case of Hong Kong).Footnote 227 The reversion of the Main Market to a more self-regulatory approach (as it had in the period before 2000) may be a too drastic and regressive step for the UK to take (and itself creates potential conflicts of interest). However, a more forward-looking system could be developed if the mission of the FCA were re-evaluated to ensure that as well as protecting consumers and the UK financial system, it has more of a stake in the upside of UK companies, by also embracing responsibility for the growth, competitiveness and success of the UK markets and economy.Footnote 228

X. Conclusion

Although a few steps behind other major exchanges, the UK's premium tier has finally commenced climbing the hill towards an acceptance of dual-class shares, with a view to attracting innovative, high-growth companies to the market. Unlike the US though, where dual-class shares structures are subject to very few regulatory constraints, the regulatory environment of the UK and the prominence of UK institutional investors, who are generally hostile to dual-class shares, will inevitably result in the use of dual-class shares structures on the premium tier being conditional upon the adoption of measures that protect public shareholders. Such protective measures are not necessarily undesirable, and, indeed, many exchanges, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, Shanghai and India also mandate investor protections in this regard. However, a balance must be maintained that reduces the risks that the interests of public shareholders will be excessively expropriated, while not blunting the very benefits of dual-class shares that attract founders to adopt the structure and list on the public markets. A premium tier package has been suggested in this article that combines two features. First, focused event-driven sunset clauses that convert enhanced-voting into one share, one vote shares upon the occurrence of events that could increase the risks that the interests of the public shareholders will be impaired: specifically, upon the holder ceasing to be a director, transferring the enhanced-voting shares, or ceasing to own sufficient “skin-in-the-game”. Second, provisions that protect against abuse of dual-class shares ab initio: specifically, ensuring that a separate public shareholder vote is required to effect certain corporate actions that could potentially be used to harm public shareholder interests. The possibility of granting public shareholders more robust independent director appointment rights has also been proposed.Footnote 229

The package that has been proposed in this article deviates though from the Review's curious curate's egg of a package for premium tier dual-class shares structures. The Review's proposals, when factoring in the conditions attached, do not represent “genuine” dual-class shares and amount to little more than, effectively, a five-year, takeover-blocking golden share and a five-year guaranteed founder board seat. Although the premium tier rules on dual-class shares are likely to evolve and shift over many years, the FCA must fundamentally accept the reasons for founders adopting dual-class shares structures, otherwise any initiatives to introduce “dual-class shares-lite” will not spawn the flood of high-growth, innovative, early-stage IPOs envisaged. Such companies have numerous other options, ranging from dual-class shares listings on foreign exchanges and lucrative buy-outs by larger companies, to exploitation of the rich availability of private capital.

Why, though, may the UK risk the worst of both worlds, that is, relaxation of the high corporate governance standards of the premium tier without any meaningful upside in attracting listings? The answer lies in the nature of the FCA as regulator of the LSE. With its mission to protect consumers and the financial markets, the FCA will be primarily focused on ensuring that listed company controversies do not occur, thus protecting against the downside rather than promoting the upside. Such an approach also bolsters the outsized influence that UK institutional shareholders, who have been antagonistic to dual-class shares, have enjoyed for decades. It is not a surprise, therefore, that shareholder rights take priority to attracting high-growth, founder-led companies to the premium tier. However, if the UK continues to disproportionately favour the views of UK institutional investors, it will potentially move in a different direction to the other major global exchanges where dual-class shares structures are being welcomed more openly. A balance needs to be struck, which may require a review of the FCA's raison d’être, with perhaps a shift to the regulator bearing some accountability for the health, competitiveness and success of the UK economy alongside its watchdog role in protecting consumers and the integrity of the financial markets. With respect to dual-class shares, without that right balance, even as the UK climbs the steep hill towards dual-class shares acceptance, it could fall right back down again.