Introduction

Ivory is a special raw material, with a long history going back to at least the Upper Palaeolithic (c. 43,000–9700 bc, according to Walker et al. Reference Walker, Johnsen and Rasmussen2009) when it was used to make elaborate ornaments as well as remarkable zoomorphic and anthropomorphic (mostly female) figurines (e.g. Schwab & Vercoutère Reference Schwab and Vercoutère2018; Wolf & Heckel Reference Wolf and Heckel2018). Historically, it has been used to manufacture a wide range of mostly sumptuous objects, ranging from personal ornaments (bracelets, necklaces, combs), to art (sculpture, furniture) and a plethora of other artefacts, such as parts of musical instruments. Combined with its aesthetic and cultural appeal, its physical properties, which render it fairly resistant to diagenetic processes, make ivory a unique indicator in the study of ancient crafts, arts, exchange and socio-cultural organization.

But what exactly is ivory? This term is often used to designate different types of large teeth in large mammals (as in the case of the hippopotamus: Ilan Reference Ilan, Finkelstein, Robin and Römer2013; Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska1984; Tournavitou Reference Tournavitou1995), but in the vast majority of the literature, it is more specifically understood as synonymous with the dentine of the incisors evolved as tusks of the proboscideans and their evolutionary relatives, such as Elephas (Palaeoloxodon) antiquus, Mammuthus, etc., and not the rest of their teeth. In this paper, we will use the term in this sense. In the case of elephants, ivory is obtained from the second upper incisors in continuous growth (Virág Reference Virág2012, 1406), called ‘tusks’. The dental formula is 1/0, 0/0, 3/3, 3/3. The upper incisor that remains on each side is the second (I2), which is replaced by the permanent tooth between 6 and 12 months of age when it is only about 5 cm long (Feldhamer et al. Reference Feldhamer, Drickamer, Vessey, Merritt and Krajewski1999, 314).

Ivory lies at the core of research on exotic resources in Iberian prehistory. Since the end of the nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth, ivory has been recovered from Late Neolithic, Copper Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age contexts, raising a great deal of interest among scholars (e.g. Camps Reference Camps1960; Götze Reference Götze and Ebert1925; Harrison & Gilman Reference Harrison, Gilman and Markotic1977; Jodin Reference Jodin1957; Leisner & Leisner Reference Leisner and Leisner1943; Poyato Holgado & Hernando Grande Reference Poyato Holgado, Hernando Grande and Ripoll Perelló1988; Reference Serra-Rafols and EbertSerra Ràfols 1925; Siret Reference Siret1913). This interest has increased in the last two decades, as reflected by a very substantial body of literature (for the third and second millennia bce, see e.g. Barciela González Reference Barciela González, Ramos Sainz, González Urquijo and Baena2007; Reference Barciela González, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012; Reference Barciela González2015; Cardoso & Schuhmacher Reference Cardoso, Schuhmacher, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012; García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño, Schuhmacher, Wheatley and Banerjee2013; Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b; Liesau Von Lettow-Vorbeck & Moreno Reference Liesau Von Lettow-Vorbeck, Moreno, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012; Liesau Von Lettow-Vorbeck & Schuhmacher Reference Liesau Von Lettow-Vorbeck, Schuhmacher, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012; Liesau Von Lettow-Vorbeck et al. Reference Liesau Von Lettow-Vorbeck, Banerjee, Schwarz, Blasco Bosqued, Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck and Ríos Mendoza2011; López Padilla Reference López Padilla, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012; López Padilla & Hernández Pérez Reference López Padilla, Hernández Pérez, Banerjee and Eckmann2011; Luciañez-Triviño Reference Luciañez-Triviño2018; Luciañez-Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016; Luciañez-Triviño et al. Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán and Schuhmacher2014; Morillo León et al. Reference Morillo León, Pau and Guilaine2018; Nocete Calvo et al. Reference Nocete Calvo, Vargas Jiménez, Schuhmacher, Banerjee and Dindorf2013; Pascual Benito Reference Pascual Benito, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012; Pau et al. Reference Pau, Morillo León, Cámara Serrano and Molina González2018; Schuhmacher Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012a,Reference Schuhmacherb; Reference Schuhmacher and Valera2013; Reference Schuhmacher2016; Reference Schuhmacher, Bartelheim, Bueno Ramirez and Kunst2017; Schuhmacher & Banerjee Reference Schuhmacher and Banerjee2012; Schuhmacher et al. Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, Dindorf, Nocete Calvo, Vargas Jiménez, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013a,Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, Dindorf, Sastri and Sauvageb; Valera Reference Valera2010; Reference Valera, Vilaça and Simas de Aguiar2020; Valera et al. Reference Valera, Schuhmacher and Banerjee2015; Vargas Jiménez et al. Reference Vargas Jiménez, Nocete Calvo, Schuhmacher, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012). The literature on Iberian late prehistoric ivory is so vast that it greatly exceeds the scope of this paper—for a recent synthesis, see Luciañez-Triviño (Reference Luciañez-Triviño2018). Our aim here is not to review the existing literature but to present a discussion of the roles played by ivory in the crafting of social and cultural idiosyncrasies (understood here as cultural practices or patterns peculiar to an individual or group of individuals, who used them to differentiate themselves from others, thus creating a sense of identity) during the Copper Age. In this period, the use of this raw material witnessed a true ‘explosion’, undoubtedly in connection with wider social and cultural phenomena. This discussion is based on a completely new analysis of the evidence obtained at Valencina de la Concepción (Seville, southern Spain), a site that lies at the forefront of current debates on Chalcolithic Iberia and which, as recent analyses have shown, offers not only the largest bulk of ivory for that period in Europe, but also a unique assemblage of artefacts, including finely crafted objects and unworked tusks (e.g. García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño, Schuhmacher, Wheatley and Banerjee2013; Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b; Luciañez-Triviño Reference Luciañez-Triviño2018; Luciañez-Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016; Luciañez-Triviño et al. Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán and Schuhmacher2014; Nocete Calvo et al. Reference Nocete Calvo, Vargas Jiménez, Schuhmacher, Banerjee and Dindorf2013; Schuhmacher et al. Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, Dindorf, Nocete Calvo, Vargas Jiménez, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013a; Vargas Jiménez et al. Reference Vargas Jiménez, Nocete Calvo, Schuhmacher, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012). The Valencina material provides an excellent basis to examine the social and cultural roles played by ivory among early complex societies, including types of objects, manufacturing processes, consumption, social significance, as well as conservation. As will be described below, our approach is based on a multi-disciplinary methodology that combines archaeology, experimentation and conservation-restoration (Luciañez-Triviño Reference Luciañez-Triviño2018).

The evidence

The Copper Age mega-site of Valencina de la Concepción-Castilleja de Guzmán (herein Valencina) is located about 6 km away from the historic centre of the modern city of Seville, in the north Aljarafe (Fig. 1). Activity at the site began c. 3200 cal. bce and ended c. 2300 cal. bce (García Sanjuan et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez and Cáceres Puro2018a). During the Chalcolithic, Valencina occupied a prominent place in an area of high strategic value for its proximity to several biotic and abiotic resources of great importance (García Sanjuán Reference García Sanjuán, Bartelheim, Bueno Ramírez and Kunst2017; Vargas Jimenez et al. Reference Vargas Jiménez, Nocete Calvo and Ortega Gordillo2010).

Figure 1. Location of Valencina de la Concepción and other late prehistoric sites of the Guadalquivir basin showing the approximate coastline in the third millennium bc. (Source: García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez and Cáceres Puro2018a: fig. 1. David Wheatley design from data courtesy of NASA EOSDIS LandProcesses Distributed Active Archive Center (LP DAAC), USGS/Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Center, Sioux Falls, South Dakota.)

Research at Valencina has made significant advances over the last decade. This has led to a more qualified assessment of processes associated with early social complexity, such as economic intensification, metallurgical production, craft specialization and social inequality (contributions to these debates in English include Costa Caramé et al. Reference Costa Caramé, Díaz-Zorita Bonilla, García Sanjuán and Wheatley2010; Inacio et al. Reference Inacio, Nocete Calvo, Nieto Liñán, Rodríguez Bayona, Abril López and Scarcella2011; García Sanjuán & Murillo-Barroso Reference García Sanjuán, Murillo-Barroso, Cruz Berrocal, García Sanjuán and Gilman2013; Garcia Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez and Cáceres Puro2018a; Nocete Calvo et al. Reference Nocete Calvo, Queipo De Llano and Sáenz2008; Rogerio-Candelera et al. Reference Rogerio-Candelera, Karen Herrera and Millar2013; Wheatley et al. Reference Wheatley, Strutt, García Sanjuán, Peinado Cucarella and Mora Molina2012), based both on a stronger chronometric basis (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez and Cáceres Puro2018a) and a more precise understanding of exogenous raw materials, such as ivory, cinnabar, amber, gold, rock crystal and other lithic resources (e.g. García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Lozano Rodríguez, Sánchez Lirazo, Gibaja Bao, Aranda Sánchez, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016b; Hunt Ortiz & Hurtado Pérez Reference Ortiz, & V, Pérez, Sainz Carrasco, López Romero, Cano Díaz-Tendero and Calvo Carcía2010; Hunt Ortiz et al. Reference Hunt Ortiz, Consuegra Rodríguez, Díaz Del Río Español, Hurtado-Pérez, Montero-Ruiz, Ortiz, Puche, Rábano and Mazadiego2011; Luciañez-Triviño Reference Luciañez-Triviño2018; Luciañez-Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016; Luciañez-Triviño et al. Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán and Schuhmacher2014; Morgado Rodríguez et al. Reference Morgado Rodríguez, Lozano, García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño, Odriozola, Lamarca Irisarri and Fernández Flores2016; Murillo-Barroso Reference Murillo-Barroso, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016a,Reference Murillo-Barroso, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonillab; Odriozola Lloret & García Sanjuán Reference Odriozola Lloret, García Sanjuán, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013; Rogerio-Candelera et al. Reference Rogerio-Candelera, Karen Herrera and Millar2013; Schuhmacher et al. Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, Dindorf, Nocete Calvo, Vargas Jiménez, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013a). For a synthesis of the history of the research at the site, see García Sanjuán (Reference García Sanjuán, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013) and García Sanjuán et al. (Reference García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez and Cáceres Puro2018a).

Our study includes all the ivory known to date from the site, that is, 384 artefacts, with an estimated total weight of 8.8 kg, from 12 different features belonging to 8 of its sectors (Fig. 2). Of course, the state of preservation is a major issue for the identification of the raw material and its technological analysis. Significant differences of preservation have been found between different sectors, or even between objects from the same structure or assemblage. In general terms, the evidence is highly fragmentary, with few complete artefacts. The high degree of fragmentation has made it very difficult to obtain a ‘Minimum Artefact Number’. For that reason, sometimes it has been necessary to count groups of fragments as a single item.

Figure 2. Sectors of Valencina with ivory.

Tables 1 and 2 provide a synthesis of the contextual data of the features studied in this paper. Here we provide a short description of the sectors of the site to which they belong.

Table 1. Summary of Valencina sectors under study.

Table 2. Summary of the contextual data of the structures with ivory.

The Instituto de Enseñanza Secundaria (IES sector) is located roughly at the centre of the site. It was excavated in 2005–06, revealing over 150 negative features (sub-circular, circular, oval or polylobulated pits and shallow basins), mostly of prehistoric date (Vargas Jiménez et al. Reference Vargas Jiménez, Nocete Calvo and Ortega Gordillo2010). They seem to have served a variety of purposes, including metallurgical production, dwelling and burial (Nocete Calvo et al. Reference Nocete Calvo, Vargas Jiménez, Schuhmacher, Banerjee and Dindorf2013; Vargas Jiménez et al. Reference Vargas Jiménez, Nocete Calvo and Ortega Gordillo2010). Only one of those structures provided ivory items: Structure 402, an oval pit containing a single episode of filling.

The DIA Sector is located barely 50 m to the west of the IES, neighbouring the Matarrubilla Partial Plan Sector (hereafter PP-Matarrubilla) to the south. Excavations carried out in 2014 revealed multiple negative Copper Age structures (Ortega Gordillo Reference Ortega Gordillo2015). The finds from this excavation are still under study, so the results are provisional. According to our study, however, two features contained ivory: Structures UC5 and UC63, neither of which has been radiocarbon dated, unfortunately.

The PP-Matarrubilla sector, located to the south of the DIA sector, was excavated in 2001, 2003 and 2004, revealing a total of 198 prehistoric features (Nocete Calvo et al. Reference Nocete Calvo, Queipo De Llano and Sáenz2008, 718). From this sector, we had access to only one artefact, the lower part of an anthropomorphic male figurine (4.8 cm in length), about which unfortunately not much contextual information is available (Hurtado Pérez Reference Hurtado Pérez, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013, 313–14). The artefact is associated with the fill of structure #50, which according to its excavators is defined by the presence of a living space (max. 3.70 m long and 2.40 m wide) and an attached well (max. 2.90×2.70 m). It has not been possible to confirm in which of the structures excavated in this intervention the piece appeared (Manuel Vargas Jiménez pers. comm., 2018).

The Montelirio tholos is located in the southeastern corner of the site, in the town of Castilleja de Guzmán. A major monograph (Fernández Flores et al. Reference Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016) provides a detailed description of the architecture, finds and bio-archaeological record of this remarkable monument, dated to the twenty-ninth/twenty-eighth centuries bce. A second monograph is currently in preparation (Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Rodríguez-Rellán and Luciañez-TriviñoGarcía Sanjuán et al. forthcoming). Montelirio is closely related both chronologically and socially to the neighbouring PP4-Montelirio sector, and particularly to tomb Structure 10.042–10.049, located barely 200 m to the north, where the so-called ‘Ivory Merchant’ was found (García Sanjuán et al. Reference Rogerio-Candelera, Karen Herrera and Millar2013; Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b): see description below. Montelirio is one of the largest Copper Age monuments in Iberia and has provided a suite of evidence that has allowed debate on the site to broaden—for a discussion, see García Sanjuán et al. (Reference García Sanjuán, Scarre and Wheatley2017; Reference García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez and Cáceres Puro2018a,Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Rischb,Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño and Cintas-Peñac).

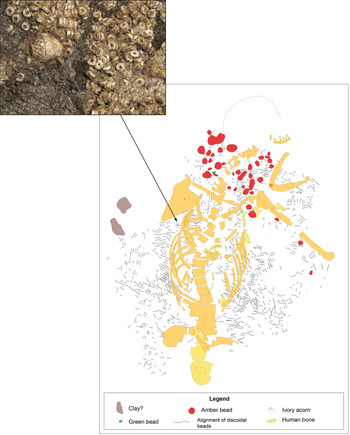

The PP4-Montelirio sector is located in the southeastern part of the site, barely 100 m to the north of the Montelirio tholos. Excavations undertaken between 2007 and 2008 revealed 134 Copper Age features, both megalithic and non-megalithic, of which 61 contained human remains (Mora Molina et al. Reference Mora Molina, García Sanjuán, Peinado Cucarella, Wheatley, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013). Still unpublished radiocarbon dates reveal that this sector was used over a relatively short period of time between 3000 and 2800 bce. Despite the large number of structures, osseous artefacts are few in number (n = 46) and almost the whole assemblage comes from Structure 10.042–10.049. The architecture, material culture and skeletal remains found in this tomb have already been described in detail elsewhere (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Díaz-Guardamino Uribe, Escudero Carrillo, Luciañez-Triviño, Mora Molina, Robles Carrasco, Muller and Hinz2019). However, it is important to note that the single primary inhumation found in the lower level (UE664) of Structure 10.049 (a probable young male: Robles Carrasco & Díaz-Zorita Bonilla Reference Robles Carrasco, Díaz-Zorita Bonilla, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013, 377) presented a remarkable set of grave goods (Fig. 3). Above this young man (UE535), another major assemblage of artefacts was laid, in this case without connection to human remains. This individual, nicknamed the ‘Ivory Merchant’, has been interpreted as a ‘Big Man’ or leader in the social history of Valencina (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b,Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño and Cintas-Peñac).

Figure 3. Human remains and grave goods of the buried adult individual found at the lower level (UE664) of the chamber of Structure 10.049. (Source: García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Díaz-Guardamino Uribe, Escudero Carrillo, Luciañez-Triviño, Mora Molina, Robles Carrasco, Muller and Hinz2019.)

The Matarrubilla tholos is also located in the southern part of the site, approximately 1 km west of Montelirio and the PP4-Montelirio sector and 700 m west of Sector Urbanización Señorío de Guzmán/Divina Pastora, described below. This major monument was discovered in 1917 and first excavated in 1918 (Obermaier Reference Obermaier1919). A second excavation was carried out in 1955 (Collantes de Terán Reference Collantes de Terán1969). Unfortunately, not a single radiocarbon date has yet been obtained for it. The excavations undertaken in 1918 and 1955 yielded very few human remains, but an important suite of high-end material culture made of exotic raw materials.

The Depósito de Agua tholos was located in the area of Castilleja de Guzmán, just next to the Montelirio tholos. A rescue excavation was carried out in June 1989, but the structure was wantonly destroyed (Santana Falcón Reference Santana Falcón1991). No radiocarbon dates are available. The limited evidence available suggests this would have been a two-chambered tholos similar to Montelirio, with earthen domes and painted slate slabs (Santana Falcón Reference Santana Falcón1991, 448–9). Very limited material culture was collected.

The Urbanización Señorío de Guzmán-Divina Pastora sector is located 300–400 m to the south of the Depósito de Agua tholos, in the Castilleja de Guzmán municipality. Here, a rescue excavation undertaken in 1996 led to the discovery of 20 prehistoric features, mostly poorly preserved, of which only six were excavated. Two main types of prehistoric tombs were identified: those made from slate slabs and those from masonry (Arteaga Matute & Cruz-Auñón Reference Arteaga Matute and Cruz-Auñón Briones2001, 644). Of the six excavated structures, three, namely Tomb 2, Tomb 3 and Tomb 5, contained ivory. No radiocarbon dating is available for any of them.

Methodology

Methodologically, our approach to the analysis of the Valencina ivory collections is based on the following steps: (I) identification of the raw material (proboscidean ivory versus other dentines and osseous materials); (II) conservation and restoration of the items in poor state of preservation in order to achieve a correct morphological identification; (III) classification of each artefact in a category of analysis; (IV) technological study under the microscope supported by a small experimental programme; and (V) contextual analysis.

The first fundamental step in the methodology was to discriminate the raw materials. For this purpose, a stereo microscope Nikon SMZ800 with two lenses (0.5× and 2×) with magnifications up to 126×, and a digital microscope (ShuttlePix P-400R) with a 20× optical lens, and magnification up to 400×, both located at the Department of Prehistory and Archaeology of the University of Seville, were used. Observations under the microscope were then compared with the structural characteristics of different hard animal tissues according to the available bibliography (e.g. Abelová Reference Ábelová2008; Choyke & O'Connor Reference Choyke and O'Connor2013; Christensen Reference Christensen1999; Deschler-Erb Reference Deschler-Erb1998; Espinoza & Mann Reference Espinoza and Mann1991; Reference Espinoza and Mann1993; Reference Espinoza and Mann1999; Feldhamer et al. Reference Feldhamer, Drickamer, Vessey, Merritt and Krajewski1999; Haynes Reference Haynes1991; Kardong Reference Kardong1999; Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska1990; Locke Reference Locke2008; MacGregor Reference MacGregor1985; Rijkelijkhuizen Reference Rijkelijkhuizen2008; Tolksdorf et al. Reference Tolksdorf, Veil, Kuzu, Ligouis, Staesche and Breest2015; Virág Reference Virág2012) and with our own reference collection. In some cases, a fundamental part of the research was the conservation treatment and restoration of the remains, a laborious and time-consuming task which was, nevertheless, utterly necessary in order to reconstruct and identify some of the most sophisticated artefacts (Luciañez-Triviño et al. Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán and Schuhmacher2014).

Rather than focusing exclusively on the end products, that is, the finished objects, our research sought to understand all aspects involved in the ivory chaîne opératoire, from the supply of the raw material and the manufacturing processes to end use, re-use and discard of the artefacts (i.e. their biography). Therefore, technical products such as raw material blocks, blanks, pre-forms (or roughouts) and debris (or production waste) were very much taken into account. In this way, the elements or categories of analysis used to classify the items in this collection include all these categories, according to general definitions set by Averbouh (Reference Averbouh, Choyke and Bartosiewicz2001). However, the specific categories for ivory technology were defined by us. Finished objects are the ultimate goal of the chaîne opératoire and are generally the best-known products, mainly due to abundant typological studies. Finished objects have been categorized by integrating traditional terms into one of the two forms of tusk exploitation identified by us. To determine the forms of exploitation of the tusks, information has been collected on the debris, the shape of the finished objects and the characteristics of the raw material observable in them (which indicate the relative position of the object within the tusk).

The specifics of our research on ivory technology (including experimentation) go well beyond the scope of this paper and will be published separately. Briefly explained, to date, according to two modes of action on the raw material in relation to the longitudinal axis of the block (we understand the longitudinal axis as the distance that separates the tip of the tusk from the base), we have identified the transversal exploitation (perpendicular action to the longitudinal axis) and the longitudinal exploitation (parallel action to the longitudinal axis). Through transversal exploitation, blanks were obtained to manufacture the following types of objects: (T.I) Recipients and related artefacts: rectangular boxes, cylindrical mouths, curved/oval base vessels, cornucopia-like objects and ‘others’ (such as ferrules or handle tops); (T.II) Perforated objects: rings and bracelets; and (T.III) Undetermined: dowel-like objects. Among the types of objects obtained through longitudinal exploitation are: (L.I) Recipients and related artefacts: handles and hilts; (L.II) Perforated objects: discs with central perforation, acorns, barrel-vault beads and double-perforated square beads; (L.III) Objects on longitudinal plaques: decorated or plain and perforated plaques, and lids; (L.IV) Barbed/Toothed elements: combs and ornamental combs; and (L.V) Figurines: human, animal, vegetal figurines or other shapes. A significant number of zoomorphic figurines were documented in the Montelirio tholos (Luciañez-Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016, 257, fig. 9) that we believe were part of the decoration of other objects, such as combs. Today, they are free-standing due to fragmentation, but their technical characteristics indicate that they were obtained by longitudinal exploitation.

Valencina's ivory objects feature abundant and diverse decorations, which can be divided into decorations in low relief and openwork. The remains of painted decorations are neither evident nor abundant, and only one possible case of colour application was documented.

The decorations in low relief mainly represent motifs created through the combination of lines or geometric forms and they often appear in bands (Fig. 4). The following patterns have been identified:

-

(I)Diamond: made by deep straight grooves, generally with an open V section, which, when crossed, generate square or almost square relief spaces in the form of four-sided pyramids, or truncated pyramids (flattened cusps). They generally make up an all-covering decoration, which affects all or a large part of the surface. Thus, it can be found on the entire outer face of objects such as vessels or in bands in composite decorations.

-

(II)Mesh: motif with appearance of a relief-like mesh, leaving the intermediate spaces slightly bulky. They generally make up an extensive and covering decoration.

-

(III)Opposed zigzag: made by continuous zigzag lines in relief, which adjacently face their vertices. They generally cover the whole surface of the object.

-

(IV)Rhomboid motif: made from grooves of generally V-shaped section of little depth that intersect with each other leaving rhomboidal spaces in relief. It is used as a covering decoration and for the elaboration of the acorn's cupule.

-

(V)Inverted triangles: several parallel lines that change their orientation with regular frequency, thus creating triangles.

-

(VI)Herringbone pattern: two bands of parallel lines in reverse direction that form a pattern similar to a cereal ear.

-

(VII)Straight parallel lines: in relief made with incisions or grooves.

-

(VIII)Convex protrusions (‘mamelones’).

-

(IX)Cord: relief pattern with a concave profile that protrudes from the surface up to c. 3 mm, and can be rectilinear or curved, adapting to the contour of the piece.

-

(X)Adjacent barrel vaults: motif giving appearance to the surface of attached tubes (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Schematic representation of low-relief patterns: (A) diamond;(B) mesh;(C) opposite zigzag;(D) rhomboid;(E) combination of decorations (from top to bottom) straight parallel lines, inverted triangles and herringbone pattern.

Figure 5. Schematic representation of a barrel-vault bead and adjacent barrel vaults decoration.

The openwork decoration has only been identified in the Montelirio combs and the motifs represented are exclusively zoomorphic and ‘opposing canes’. The identified zoomorphic motifs appear to represent quadrupeds, possibly suids (pigs or wild boars), but not all are easily recognizable (Luciañez-Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016). Only one case represents a bird. The so-called ‘opposing canes’ are a main motif in the openwork decoration of the Montelirio combs. It is based on a series of elongated ‘bodies’ that curve towards the centre of the piece and are topped by spheres. They appear opposite to each other, in variable numbers (odd or even) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Montelirio combs with openwork decoration.

Results

Scales of consumption

With a recorded 8.8 kg, Valencina has yielded what to date is by far the largest ivory collection in Chalcolithic Iberia (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b; Luciañez-Triviño Reference Luciañez-Triviño2018) and one of the largest (if not the largest) for western Europe. With few exceptions, the main assemblages of this raw material are associated with major megalithic monuments such as Montelirio, Matarrubilla and Structure 10.042–10.049. In the structures in which ivory has been found, ivory is the most widely used osseous raw material, representing 65 per cent of the worked osseous industry, followed by animal bone (21 per cent) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Osseous raw materials by structure.

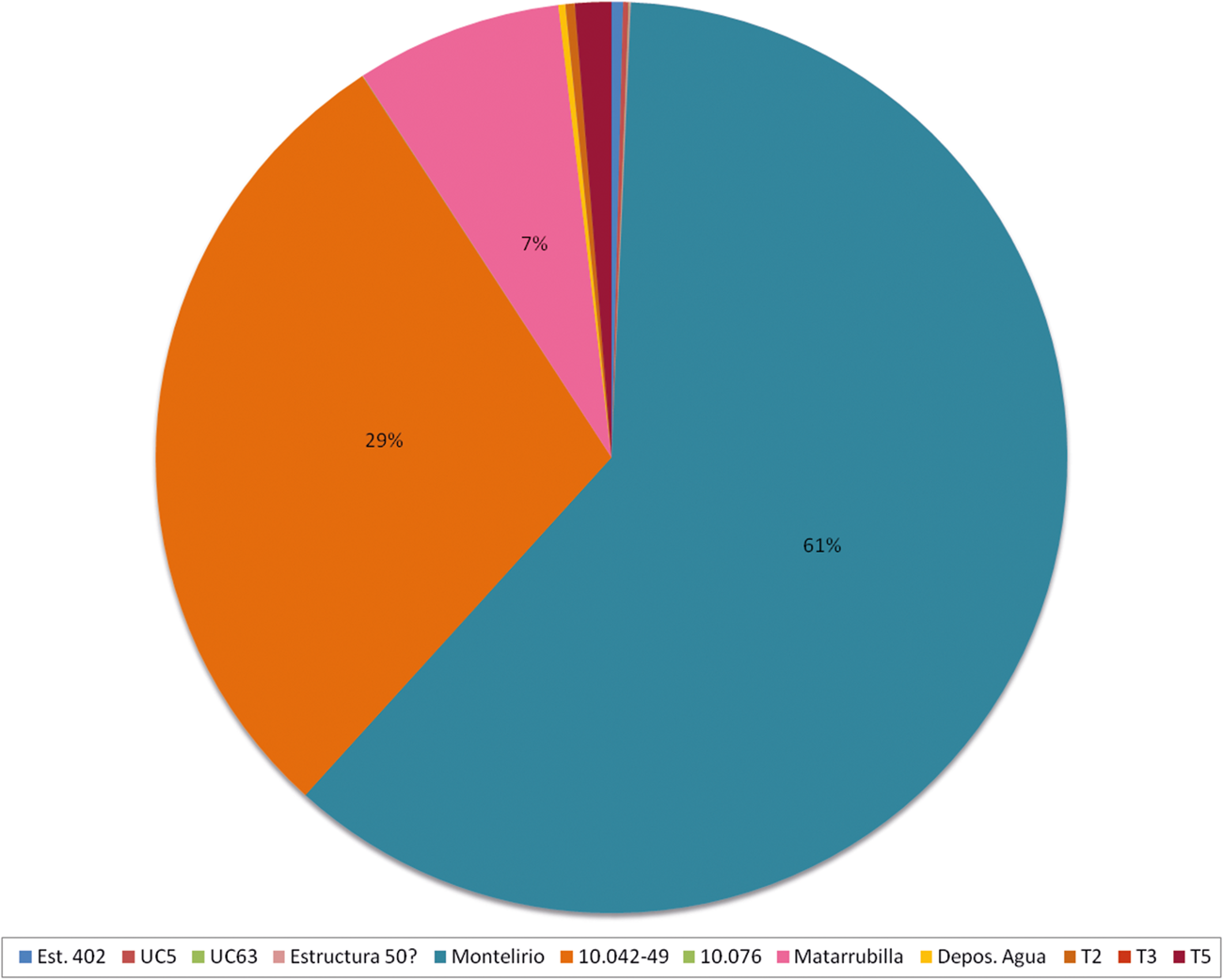

The tomb with the greatest total number of objects (complete artefacts, fragments and groups of fragments) is Montelirio with 105 items, followed by Matarrubilla with 81 and Structure 10.042–10.049 with 21 (Table 2; Fig. 8). Considering the total weight instead of counting artefacts changes the picture slightly, but Montelirio continues to have the largest collection with 5.387 kg (Small Chamber = 4.607 kg; Large Chamber = 0.7 kg), followed by Structure 10.042–10.049 with 2.565 kg in total (10.049, base level = 1.883 kg; 10.049, upper level = 0.649 kg; 10.042 = 0.032 kg), and by Matarrubilla with 0.646 kg (Luciañez-Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016). We have discussed an interpretation of these numerical data elsewhere (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b). The disparity between the object count and the total weight responds to the presence of heavy segments of elephant tusks. When these are excluded, the weight results read like this: Montelirio = 0.536 kg; Structure 10.042–10.049 = 1394 kg; Matarrubilla = 0.320 kg. This is consistent with the size of the objects deposited in each grave. The sizes of the artefacts from Structure 10.042–10.049 are much larger: e.g. the plaque/sheath is c. 30 cm long in its current state, and the carved tusk measures about 40 cm. At Montelirio, the largest items are the possible container lids (maximum length between 11.7 and 12 cm) and a comb measuring c. 12 cm. At Matarrubilla, the assemblage contains basically a high number of beads (the largest is only 2.6 cm long), and the largest item (a plaque with perforations) measures only 6 cm in its current state. Considering the weight of the artefacts (excluding blocks), Structure 10.042–10.049 contains the largest amount, precisely due to the large size of the objects (Fig. 9). But in terms of total weight, Montelirio has twice as much ivory as 10.042–10.049, with 60 per cent of the total ivory of the site (Fig. 10). Therefore, 90 per cent of the ivory from Valencina is concentrated in two large monuments, especially in Montelirio.

Figure 8. Density map based on the total weight of the finds.

Figure 9. Distribution of ivory in Valencina according to the weight (g) of objects in each context.

Figure 10. Distribution of ivory in Valencina according to the total weight in each structure.

In general, the raw data on the total weight and number of ivory objects are scarce and difficult to obtain due to fragmentary publication. This limits the quantitative assessment and comparison of the Valencina collection at an Iberian and international level. Only in a partial and indicative way can we compare the Valencina data with the site of Perdigões in Portugal, where 1886 ivory items were recorded (3.4 kg). Tomb 2 stands out with 1.8 kg, while Fossa 40 yielded 1 kg of ivory (Valera Reference Valera, Vilaça and Simas de Aguiar2020, 139 and table 3). At a Mediterranean level, both in Greece and the Levant, ivory was abundant from the Bronze Age to the Hellenistic period (Fitton Reference Fitton1992). Unfortunately, apart from some exceptions, no quantitative estimates like those handled here are available. We can cite a context interpreted as a workshop in Knossos in which over 1 kg of small chips were recovered (Krzyszkowska Reference Krzyszkowska and Fitton1992, 31, n. 15). By comparison, in Valencina only 15 fragments of debris (totalling only 50 g) have been found. The differences between the amount of chips and debris at both sites suggests that interpretations concerning the existence of workshops and the probable scales of production in Iberia must be made carefully, especially regarding the interpretation of the local production of objects, as no straightforward or simple correlations exist between the former and the latter.

Morphologies and designs

As we have already mentioned, the degree of fragmentation across all of the assemblages is very high, so that the number of objects is probably over-represented. Nevertheless, through meticulous study under the microscope, a full inventory of end products was made.

At IES, Structure 402, most of the recorded items are debris (n = 12) of prismatic shapes or fragments of thin slices. Evidence of finished objects (n = 4) is scarce and difficult to interpret: an undetermined ‘recipient/receiver’ (T.I, perhaps part of a handle, like a ferrule or top), a plaque with two perforations (L.III), and two bolt-like T-shaped objects (T.III). There is no evidence of decoration on any of the pieces. Structure 50 of PP-Matarrubilla delivered the only anthropomorphic figurine of ivory found to date in Valencina. As already explained, it is the lower part of a male body (L.V) (Hurtado Pérez Reference Hurtado Pérez, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013, 313–14, figs 2–3 & 3).

For the Small Chamber of Montelirio, the morphology of 14 objects was established with certainty: one elongated handle with circular section and insertion in the axis through a blind hole (L.I); one or two objects decorated with zoomorphic figurines (combs or another type of object with openwork decoration, L.IV); decoration in the shape of a bird of a possible pin (L.V); a small decorated plaque (L.III); six acorns (L.II); and three possible combs (L.IV).These last combs show different decorations: one of them shows the same decoration on both sides (herringbone pattern), while the other specimen has different decoration on each side (mesh patterning on one side and opposite zigzag motif on the other). To this we must add the thousands of fragments catalogued as raw material, which indicate the deposition of one or two tusks. In the Large Chamber of Montelirio, 23 objects were identified: two acorns with perforations (L.II); one spiral-shaped object (L.V); two semi-circular lids (L.III); 10 perforated discs (L.II); one or two small D-section rings (T.II); one mouth of a composite object (cylindrical form with external decoration of straight parallel lines) (T.I); another possible container's mouth without decoration (T.I); two combs with zoomorphic and ‘opposing canes’ decoration (L.IV); a racquet-like plaque with a set of perforations in a circle (undeterminedobject, without parallels, L.III); and a possible small handle (L.I).

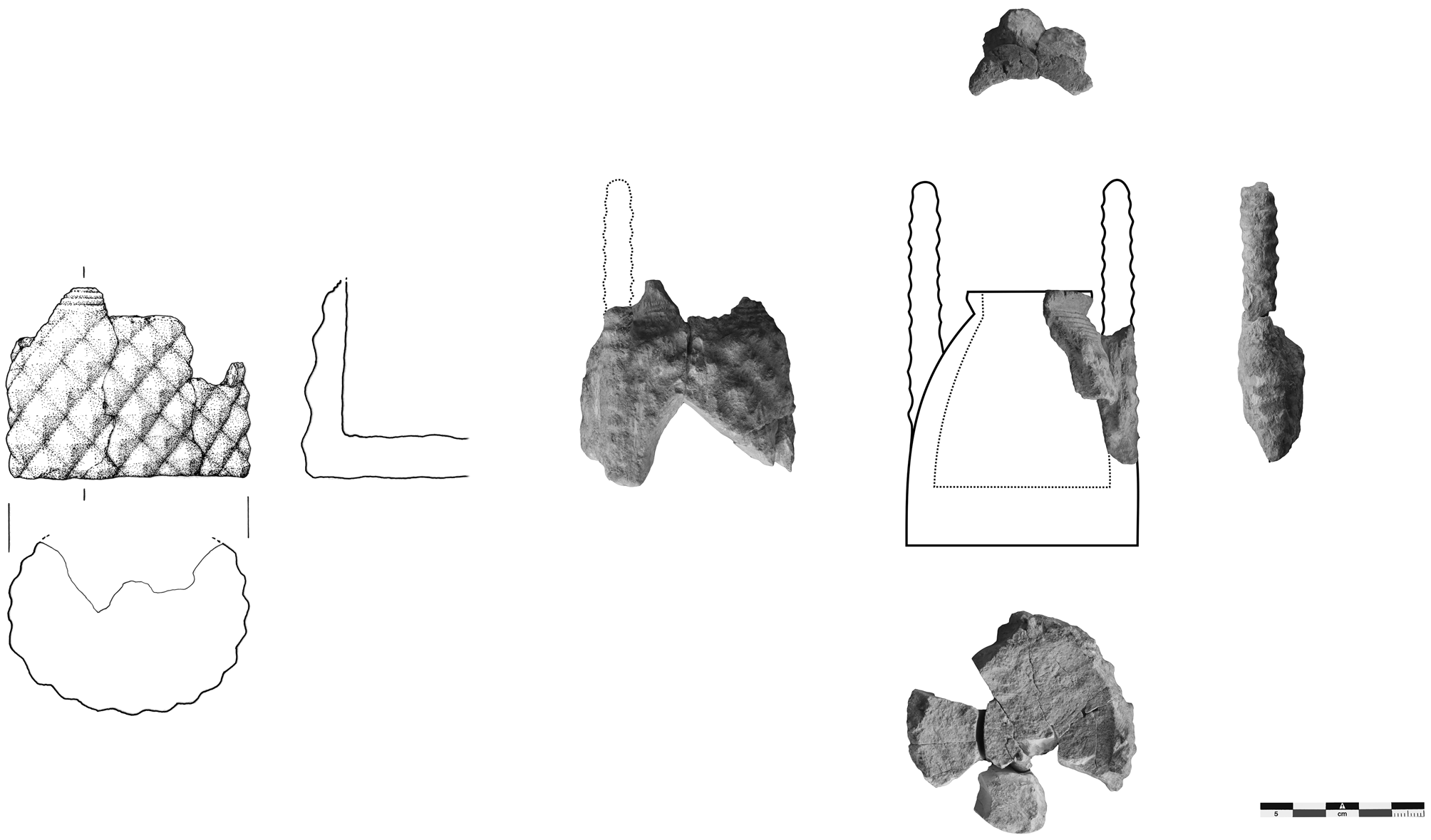

In Structure 10.049 of the PP4-Montelirio sector, six objects were securely identified for the upper depositional level: a diamond-decorated elephant tusk (T.I); one or two small D-section rings (T.II); a composite dagger hilt with mesh decoration (L.I); a decorated plaque with mesh pattern on the obverse and V perforations on the reverse (possible sheath) (L.III); and a small plaque with diamond decoration (L.III). In the lower level of Structure 10.049, in direct association with the ‘Ivory Merchant’, six objects were identified: one oval-based vessel with diamond pattern decoration (T.I); an oval-based vessel with diamond pattern decoration and two appendages (Fig. 11) (T.I); fragments of a cylindrical object (T.I); one rectangular box with diamond-pattern decoration (T.I); and two decorated combs (L.IV). One of these combs has herringbone pattern on one side (the other is poorly preserved), while the other comb has mesh pattern decoration on both sides. In addition, as mentioned above, one unworked tusk divided into three segments was deposited. In Structure 10.042 only one small rectangular box with diamond-pattern decoration (T.I) was identified (Fig. 12).

Figure 11. (Left) Oval-based vessel with diamond decoration and (right) oval-based vessel with diamond decoration and two appendages (PP4 Sector, Structure 10.049, UE664).

Figure 12. Small rectangular box (PP4 Sector, Structure 10.042).

For the Matarrubilla tholos we have identified 65 objects: 53 adjacent-barrel-vaults beads (L.II); seven double-perforated square beads (L.II); one small handle (T.I); a bracelet with herringbone pattern decoration (T.II); a fragment of a plaque with perforations in a circle (L.III); a possible pendant (L.III); and a small appliqué with a perforated tongue for its fastening (indet.). In addition, a segment of tusk (secondary block) was found.

For Urbanización Señorío de Guzmán/Divina Pastora, we have recognized a cylindrical object (T.I) for Tomb 2 and another possible cylindrical object (T.I) for Tomb 5. Some materials from Señorío de Guzmán/Divina Pastora are missing and are known only from bibliographic references. According to these, T3 yielded ivory plaques and T5 a bracelet (Arteaga Matute & Cruz-Auñón Reference Arteaga Matute and Cruz-Auñón Briones2001). The form and some technological marks observed on the surface of the material of Depósito de Agua tholos point to the deposition of objects, but unfortunately no specific morphologies have been recognized.

These data reveal six important points:

(I) 75 per cent (n = 178) of the ivories studied here are finished objects or fragments of them;

(II) in the site there are to date only 15 items of production waste;

(III) in the pits interpreted in connection with production contexts, no blanks or blocks were found, which, however, did appear in some of the tombs: one or two in the Small Chamber of Montelirio, one in Structure 10.049 (lower level) and a segment in Matarrubilla (corridor);

(IV) there is a pervasive technical uniformity across the entire Valencina assemblage, with 72 per cent of the objects obtained by longitudinal exploitation;

(V) most objects are unique;

(VI) each tomb has a singular assemblage.

Contexts of deposition

As mentioned above, the vast majority of Valencina's ivory was found inside megalithic tombs, either large or medium-sized. These are Montelirio, structures 10.042–10.049 and 10.076 in the PP4-Montelirio sector, Matarrubilla, Depósito de Agua and tombs T2, T3 and T5 in the Divina Pastora/Señorío de Guzmán sector. It is important to note that all of them are tholos-type megaliths. Four other structures where ivory was found, basically simple pits, appear to have been related to activities other than burial, possibly linked to craft and production tasks: these are UC402 from IES, UC5 and UC63 from DIA and Structure 50 from PP-Matarrubilla. However, the amount of ivory found in these non-burial features is tiny: 59.5 g. Altogether, Valencina hoards 8.8 kg of ivory.

It is therefore verified that in Valencina ivory was, in fact, almost exclusively deposited in funerary contexts, specifically in tholos-type monuments. In structures related to activities other than ritual and/or burial (such as production, storage, dwelling), ivory artefacts do not show any specific pattern of deposition. By contrast, in those tholoi, ivory always was found in the chambers, with two exceptions: Matarrubilla and Depósito de Agua. In the case of Depósito de Agua, the discovery of the ivory fragments in the corridor may be due to the destruction of the structure, as occurs with the few remains found in the corridor between the chambers of the Montelirio tholos. However, in Matarrubilla the deposition of the ivory material in the corridor is clear. No ivories were found in the Matarrubilla chamber. This unusual location suggests that the Matarrubilla ivories were deposited at a later stage in the biography of the monument. The fact that ivory is found primarily in the chambers of these great monuments may have to do with their specific relationship with the people buried in them (Montelirio and Structure 10.049)Footnote 1 or with the role played by the chambers within the rituals staged inside the monuments—see, for example, the key role played by the stela in the Large Chamber of Montelirio.

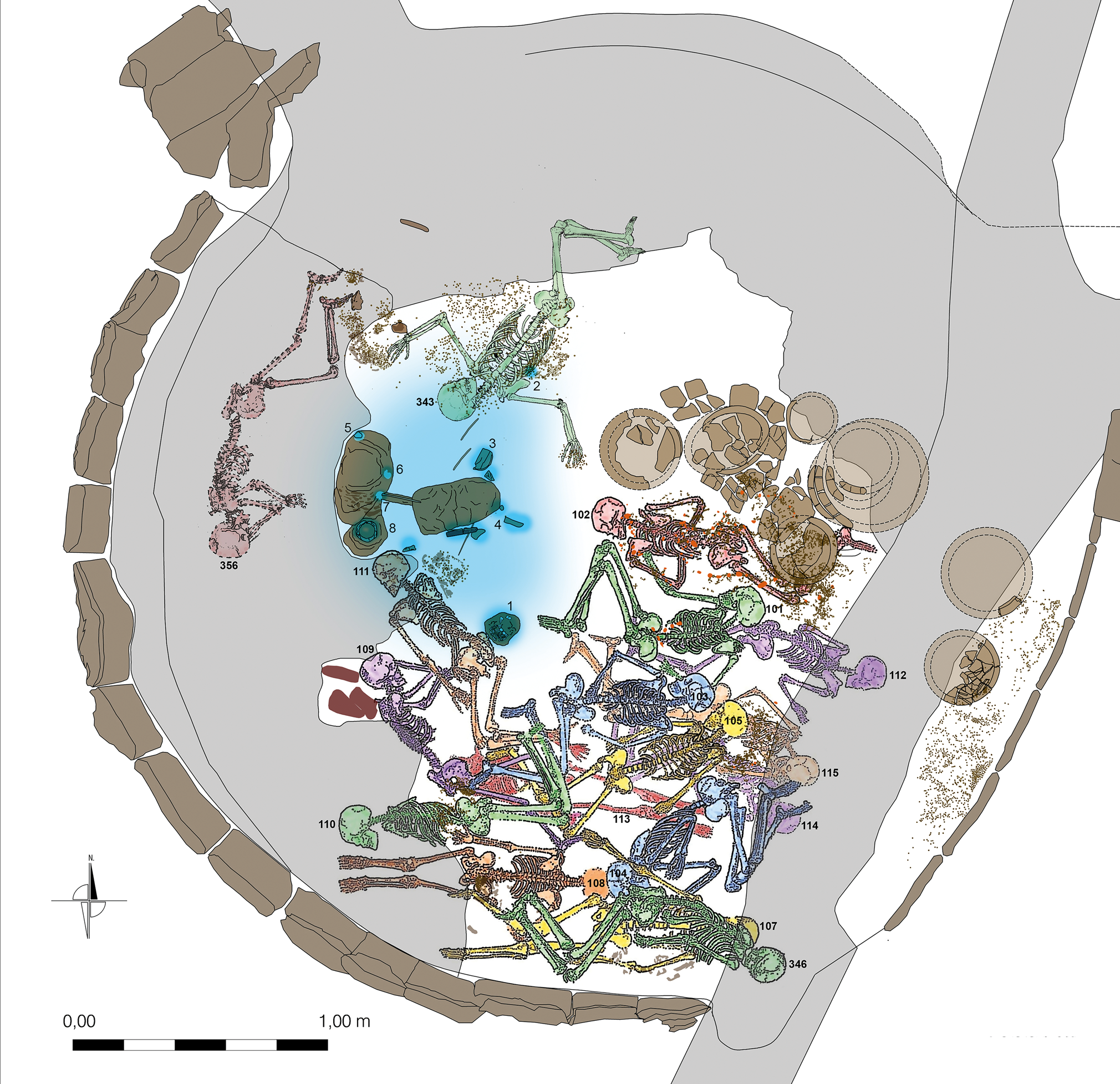

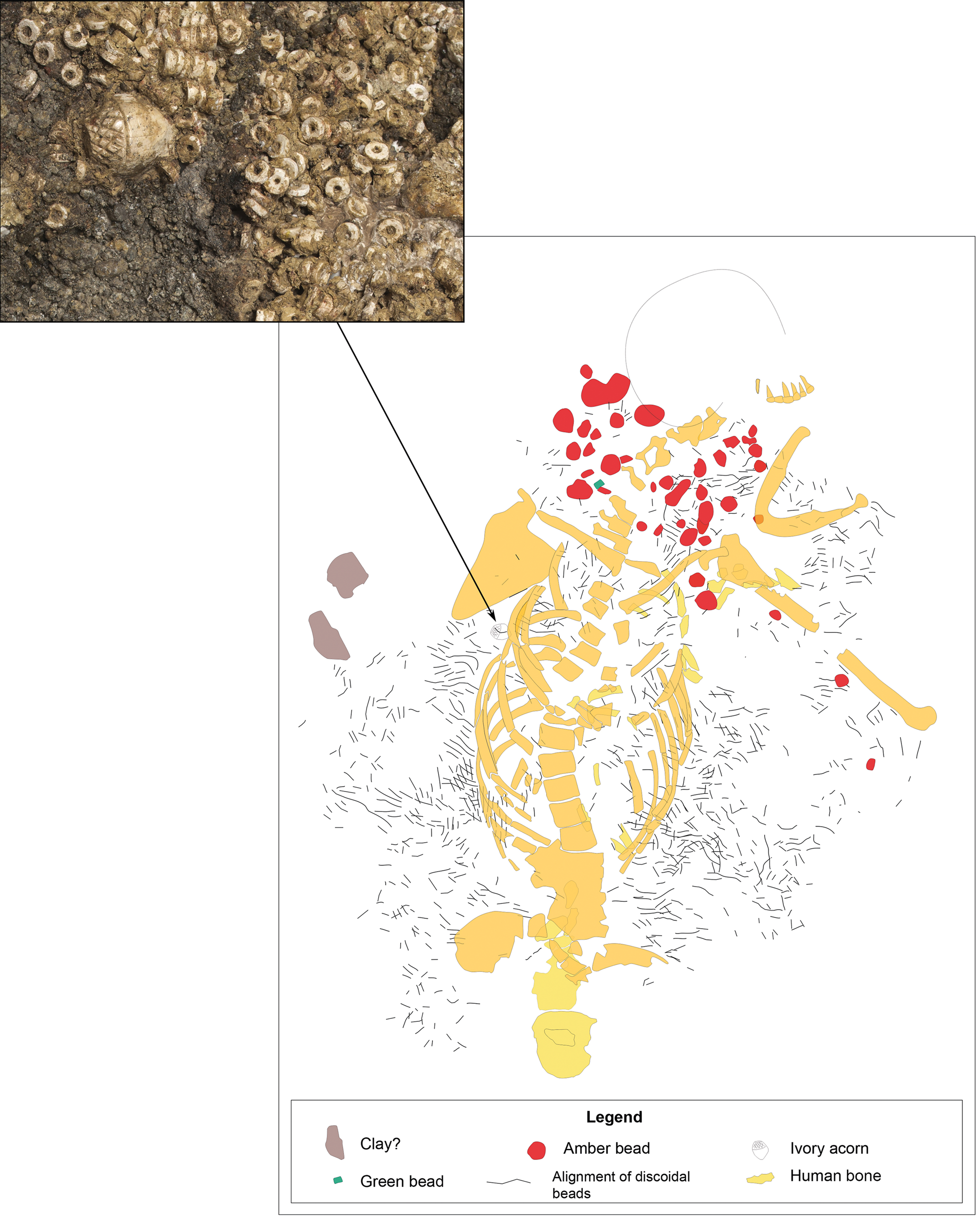

The ivories generally appear in connection with collective burials (Table 2), with two exceptions: the lower level in Structure 10.049, where the ‘Ivory Merchant’ was found, and the upper level of this very same tomb, where no human remains were found. Thus, only in the case of this young male could we speak of an individualized set of grave goods, given that all the ivory objects appeared accumulated in front of his arms, and the tusk was placed ‘framing’ his head (see Figure 3). Although badly disturbed by later activity, the bones of at least two individuals were identified in the SC of Montelirio, a chamber that shows a subtle connection with the ‘Ivory Merchant’ buried in Structure 10.049: as mentioned above, one or two elephant tusks and several comb fragments with geometric decoration were deposited in the SC (the latter with herringbone, mesh and opposite zigzag patterns of decoration), as is the case with the grave goods of the ‘Ivory Merchant’. Conversely, all the ivory artefacts of the Large Chamber appeared around the clay stela (Fig. 13) and only a single piece was related beyond doubt to one of the 20 individuals buried there: an acorn-shaped pendant found under the left shoulder-blade of individual UE343 (female, aged 24–32 years) (Fig. 14) (Díaz-Guardamino Uribe et al. Reference Díaz-Guardamino Uribe, Wheatley, Williams, Garrido Cordero, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016; Luciañez-Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016, 255). It is not possible to rule out that this acorn was a pendant used as part of an elaborate costume worn by this woman, and that it fell down with the decomposition of the body, being later located behind her back.

Figure 13. Location of the ivories in the Large Chamber of Montelirio. In blue, the area with the highest concentration. (1) comb with six zoomorphs; (2) acorn; (3) semicircular lid; (4) unrecognizable remains; (5, 6, 7) discs with central perforation; (8) mouth of container. (Source: modified from a drawing by Juan Manuel Guijo Mauri.)

Figure 14. Acorn embedded in the costume (UE344) of a female individual (UE343) in the Large Chamber of Montelirio. (Source: modified from photograph by David Wheatley and design by Marta Díaz-Guardamino Uribe and David Wheatley, in Díaz-Guardamino Uribe et al. Reference Díaz-Guardamino Uribe, Wheatley, Williams, Garrido Cordero, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016, 355–6, figs 8 & 11).

Therefore, in the LC of Montelirio it seems that the ivories form rather an offering to the stela, or a collective set of grave goods, since they were not arranged in such a way that they could be associated with specific individuals. In addition, in Montelirio some ivory artefacts are pieces or parts of other elements. Two large containers were placed behind the stela (Bueno Ramírez et al. Reference Bueno Ramírez, Balbín Behrmann, Barroso Bermejo, Carrera Ramírez, Hunt Ortiz, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016; Fernández Flores & García Sanjuán Reference Flores, L, Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016; Luciañez-Triviño& García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016). One of them was decorated with ivory discs and the other had an ivory mouth (Fig. 15). Various other objects were placed in front of the stela, including a possible semicircular box (similar to a kitchen salt-shaker) with an ivory lid (Fig. 16). Thus, the Montelirio ivories seem to constitute a collective offering, as would be the case with the ‘treasure’ or the furniture of a temple, rather than the expression of individual wealth. In fact, the human contingent found inside the Large Chamber of Montelirio was interpreted as a group of religious specialists (‘priestesses’) connected with a temple, sanctuary or oracle (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, Díaz-Zorita Bonilla, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016a, 544–5).

Figure 15. Montelirio tholos, Large Chamber. Location of ivory elements around the stele: (a) ivory mouth or top for container; (b, c, d) ivory discs decorating a container; (e) semicircular lid. (Source: modified from a photograph by Alvaro Fernández Flores.)

Figure 16. (Right) ivory semicircular lid, with (left) a hypothetical interpretation.

Discussion

We can summarize the results of the analysis presented above as a series of short points:

1. Since c. 3000–2900 bce, elephant tusks were making their way into Valencina from Africa and the Near East.

2. Together with this foreign material, fossil ivory also was being used. The origin of this fossil material is under study, and could have been equally imported or extracted from local sources: several remains of Elephas (Palaeoloxodon) antiquus and other mega-herbivores are documented in the Las Jarillas terrace, c. 17 km from Valencina (Baena-Escudero et al. Reference Baena Escudero, Fernández Caro, Guerrero Amador and Posada Simeón2014).

3. Tusks were worked by highly skilled craftspeople who applied unrivalled expertise to produce artefacts unknown both in Iberia and western Europe.

4. While transformation debris has been identified in various simple pits (IES and DIA sectors), finished objects (and especially the most sophisticated ones) are only found in major megalithic tombs such as Montelirio, Matarrubilla and Structure 10.049.

5. Ivory was a high-end commodity, on account both of the intrinsic value of the raw material and the specialized and highly skilled labour invested into it. Thus, it was used by the local elites to sustain and reinforce their social position. This is particularly clear in the case of the ‘Ivory Merchant’, the first of what appears to be a string of powerful local leaders using ivory (in conjunction with other exotica) in large-sized, lavishly furnished megalithic tombs.

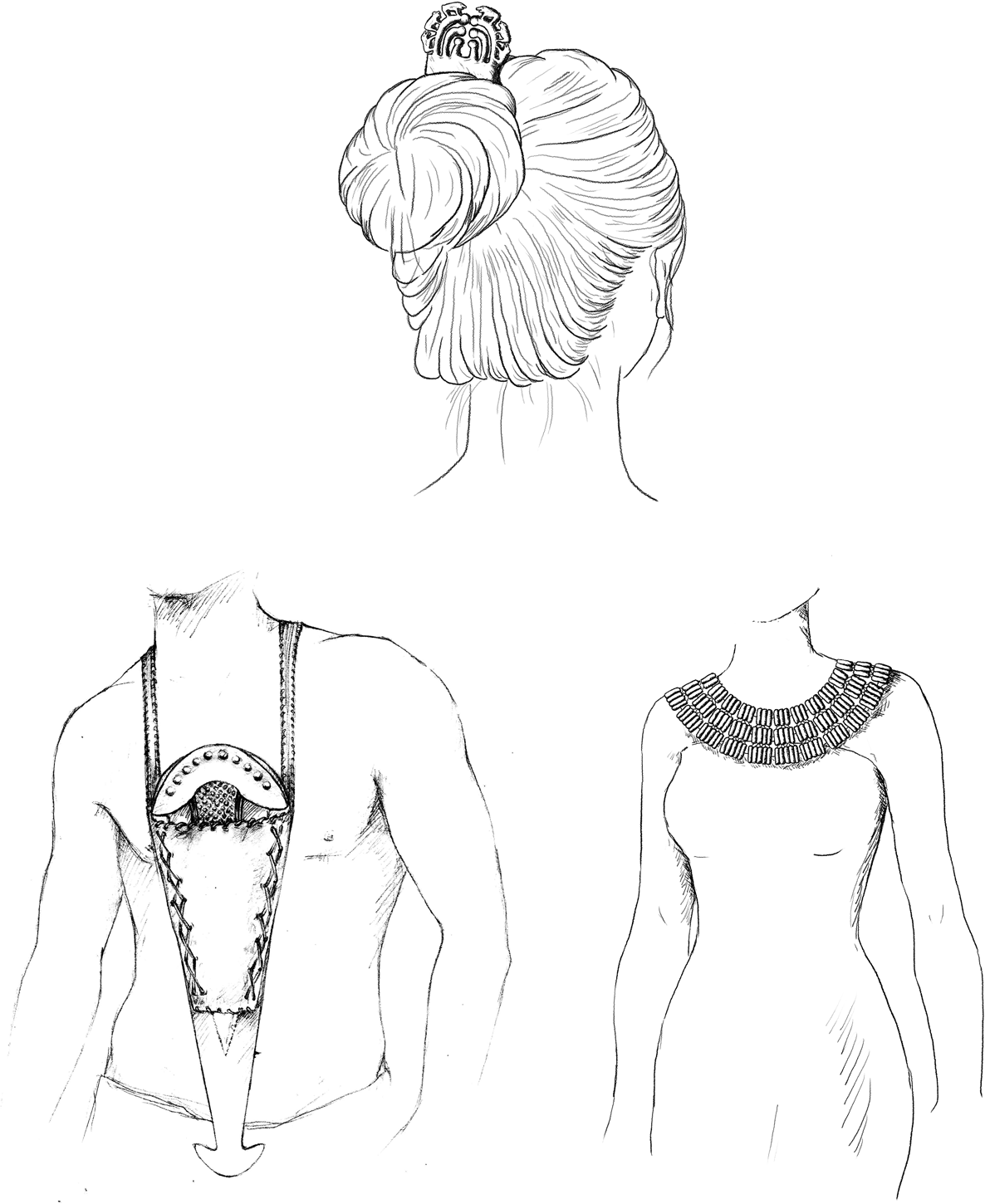

6. Ivory was not used to make utilitarian objects, but showy personal objects for display, usually attached to someone's body (combs, bracelets, pectorals, pendants and daggers).

7. Ivory was used to make distinct, unique and highly idiosyncratic artefacts which, apparently, were made only once, and for specific kinship units or corporate groups.

8. Tusk segments and whole tusks were seen as highly valuable elements per se, as demonstrated by the fact that they never appear in the simple pits that contain only production debris, but, on the contrary, feature prominently among the grave goods of high-ranking individuals, including, especially, the ‘Ivory Merchant’ and the two people buried in the Small Chamber of Montelirio.

Indeed, a striking characteristic of the Valencina ivory collection is that the exception appears to have been the rule. First, objects are unique; second, assemblages are singular and unrepeatable. Many of the objects found in Valencina are unique for this chronology, not only in the Iberian Peninsula, but, as far as we know, also in Europe and the western Mediterranean. The combs with zoomorphic decoration from Montelirio have no parallels in Valencina or in Iberia (Luciañez-Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016), nor do the container lids and mouths or the perforated discs; the possible pectoral found at Matarrubilla is also unique (Schuhmacher Reference Virág2012a; Schuhmacher et al. Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, Dindorf, Nocete Calvo, Vargas Jiménez, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013a), as are the ivory dagger hilt and sheath and the decorated tusk from Structure 10.049 (García Sanjuán et al. Reference Rogerio-Candelera, Karen Herrera and Millar2013) or the small rectangular boxes.

In Structure 10.042–10.049, objects are larger and they are covered by profusely applied decoration, always using geometric and linear motifs (such as herringbone, opposite zigzags, or mesh, diamond and rhomboid patterns). By contrast, three generations later, the size of the objects in the Montelirio tholos decreases and those decorations become anecdotal, as they appear only in some small comb fragments in the Small Chamber (Luciañez-Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez-Triviño, García Sanjuán, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016, 254, fig. 5). In Montelirio the main motifs are plants and animals (possible suids, a bird and acorns), which did not feature in the earlier assemblage of Structure 10.049. Later on, the size of the Matarrubilla objects is even smaller and none of those decorative motifs appear. Here the artefacts are smooth and the only decoration motif is barrel-vaults. Only two fragments of a bracelet in Matarrubilla have a herringbone-like decoration pattern, but their composition and execution have nothing to do with earlier items bearing these decorations.

Therefore, we observe that in the oldest burials, more ‘traditional’ decorations (geometric, diamonds, etc.) were present, but as time went on, they ended up disappearing. In this sense, Montelirio started a new and different decorative tradition inspired by natural elements, although other, more general cultural features were still present. The ivory objects from Matarrubilla, however, do not appear to display continuity with either 10.049 or Montelirio; decorations disappear and items become smaller (almost exclusively beads), which is in line with the general evolution observed in ivory objects from the middle of the third millennium bce onwards.

The clearly unique character of those three assemblages reveals the intention to create idiosyncrasies through the production and exhibition of original and unrepeatable sophisticated paraphernalia (Fig. 17). However, subtle coincidences point to a close relationship of the groups represented in each tholos with previous lineages, or individuals/groups buried in other structures. This relationship has already been suggested for Structure 10.042–10.049 and the Montelirio tholos (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b), in particular between two of the chambers of both these structures. In the Small Chamber of Montelirio and Structure 10.049, unworked tusks, objects with geometrical decoration and only one or two individuals were buried (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b, 44; Fig. 17). Another grave also located in the province of Seville presents important parallels with Structure 10.042–10.049: La Molina (Lora de Estepa). La Molina is an artificial cave, or ‘hypogeum’, where 10 individuals were buried. Among them, a young woman called ‘E1’, who probably was the last burial in the structure, had the only personalized set of grave goods, laid around her head (Juarez Martín et al. Reference Juárez Martín2010, 66). Two ivory objects of La Molina's woman E1 connect her with the material culture found in the upper level of Structure 10.049: a hollowed-out and carved, cornucopia-like elephant tusk and one ivory hilt for a flint blade (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b,Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño and Cintas-Peñac). The cornucopia-like object of La Molina is smaller (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b, 53, fig. 25) and is not completely decorated (only few lines in the open end) and the handle is completely different to the one from structure 10.049, but the similarities between these objects, both in shape or functionality, suggests some degree of temporal, cultural and social proximity between the tombs and a possible connection between the two individuals (the woman E1 of La Molina and the ‘Ivory Merchant’), which has been interpreted in terms of kinship or social bonds (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b, 52).

Figure 17. Idealized drawing of the possible use of some of the ivory objects. (Above) Ornamental comb with zoomorphic decoration from Large Chamber of Montelirio. (Left) Rock crystal dagger with ivory hilt carried inside its ivory and leather cloth sheath (based on some depictions in Bronze Age stelae) from the upper level of structure 10.049. (Right) Pectoral of adjacent-barrel-vaults beads from the corridor of Matarrubilla. (Source: García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño and Cintas-Peña2018c. Drawings by Miriam Luciañez-Triviño.)

Naturally, Valencina did not exist in isolation. In the early centuries of the third millennium bce, ivory was being consumed at other sites of southern Iberia, notably in Los Millares (southeast Spain) or Perdigões (south Portugal), with which the Valencina ivories display very few but significant connections. Despite the striking innovations, Valencina was part of a common Late Neolithic/Early Chalcolithic tradition that is noticeable in some specific features of the ivories. In general, diamond and rhomboid decorations are found throughout southern Iberia. We see them in many different raw materials, such as bone, ivory, ceramics or stone (Leisner & Leisner Reference Leisner and Leisner1943), and particularly in vessels or cylinders made from bone and ivory, which are also abundant in Portugal, for example in Pai Mogo (Laurinha) (Gallay et al. Reference Gallay, Sindler, Trindade and Da Veiga Ferreira1973) or in Perdigões (Valera et al. Reference Valera, Schuhmacher and Banerjee2015). Although abundant acorn-shaped pendants are found only in Montelirio (plus a possible one in the Depósito de Agua tholos), there are other specimens in southern Spain, such as those from Cueva Antoniana (Gilena, Seville) (Cruz-Auñón Briones & Rivero Galán Reference Cruz-Auñón Briones and Rivero Galán1987), La Pijotilla (Badajoz), Los Algarbes (Tarifa, Cádiz) (Posac Mon Reference Posac Mon1975, 113) and El Toro cave (Antequera, Málaga) (Bueno Ramírez et al. Reference Bueno Ramírez, Balbín Behrmann, Barroso Bermejo, Carrera Ramírez, Hunt Ortiz, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016, 384; Camalich Massieu et al. Reference Camalich Massieu, Gonzalez Quintero and Martín Socas1987). There is also a possible example in Monte Abrão (Portugal) (Schuhmacher Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012a, 141, fig. 42.2, pl. 2.15).

One of Valencina's most important connections with other sites is one decorated ivory comb found in Structure 10.049 (upper level, UE535, no human remains), which is almost identical to an ivory comb from Los Millares Tomb 12 (collective burial, 12 individuals: Leisner & Leisner Reference Leisner and Leisner1943, 25, and pl. 11, no. 26; Maicas Ramos Reference Maicas Ramos2007, 122) (Fig. 18) and in which, in addition, an ivory plaque with V-perforations on the back was also found. This draws an interesting connection with the ‘Ivory Merchant’. A number of tombs at Los Millares stand out for the quantity and diversity of objects (Chapman Reference Chapman1990), including all those with ivory (#5, #7, #8, #9, #12, #16, #40 and #63, except for grave #71 of doubtful attribution: Schuhmacher Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012a, 47). Ivory must have played a significant role in the definition and exhibition of power at Los Millares and other sites too.

Figure 18. (Left) Comb from Tomb 12 of Los Millares. (Right) Fragments after restoration of the comb from Structure 10.049(UE535).

Despite the meagre published contextual data, the anthropomorphic figurine of PP-Matarrubilla has special relevance for being the only human figure carved in ivory to date in Valencina. Other anthropomorphic figurines of the same style have been found in other sectors of Valencina, such as the two from Shaft 1 of Cerro de la Cabeza (Fernández Gómez & Oliva Alonso Reference Fernández Gómez and Oliva Alonso1980, fig. 4; Reference Fernández Gómez and Oliva Alonso1986, 28; Hurtado Pérez Reference Hurtado Pérez, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013) but they are made of bone or antler. In Iberia, this type of human representation, with hieratic pose and arms crossed on the belly, is made of various raw materials. Of ivory they are abundant in cremation contexts of Perdigões (Reference Valera, Schuhmacher and BanerjeeValera et al.2015). Other examples have been documented in Marroquíes Altos and Torre del Campo (Jaén), and in La Pijotilla (Badajoz) (Schumacher Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012a, 52).

Fragmentation and biographies

The striking contrast between the great morphological variability and the technological uniformity in Valencina's ivory assemblage suggests that the marked differences in the morphology of the objects were a deliberate choice. In this context, when the exception is the rule, then coincidences have a special significance.

The treatment, manipulation and alteration of the primary deposits of human skeletal remains is a proven practice in Valencina, and in other Copper Age contexts. This entailed the opening of burials for the disposal of new bodies, the relocation of existing ones and the selection of some parts (like skulls or long bones). If this was done with human bodies, why not think that a similar practice (of selection and transfer) may have occurred with objects? The subtle coincidences between the material culture recovered from some of the tholoi point out in this direction. The long-barbed arrowheads, white discoidal beads and fragments of small D-section rings found in structure 10.042, in the upper level of 10.049 and in Montelirio suggest a re-opening of the grave of the ‘Ivory Merchant’ when Montelirio was built (or used); likewise, the fragment with perforations of the corridor of Matarrubilla, which refers particularly to the racquet-likepiece found in the Large Chamber of Montelirio, and the deposition of blocks in Matarrubilla, Montelirio and Structure 10.042–10.049 suggest an awareness and even a relationship between the builders and users of these monuments, and perhaps other structures in the site. Ivory objects played an important role in these dynamics. Is it possible that the fragment of Matarrubilla is in fact a part of Montelirio's racquet-like piece? Could the small ring fragments be part of the same object, fragmented and then distributed between Structure 10.042–10.049 and Montelirio? Or could the fragmented blocks come in some cases from the same tusk? At this time, these are just hypotheses. It has not been possible to reconstruct the rings, since they are very uniform, which makes it difficult to reassemble the pieces in their original form. The rings from Montelirio and Structure 10.042–10.049 are morphologically so similar that they cannot be distinguished from one another (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño and Cintas-Peña2018c, 45, see fig. 18).

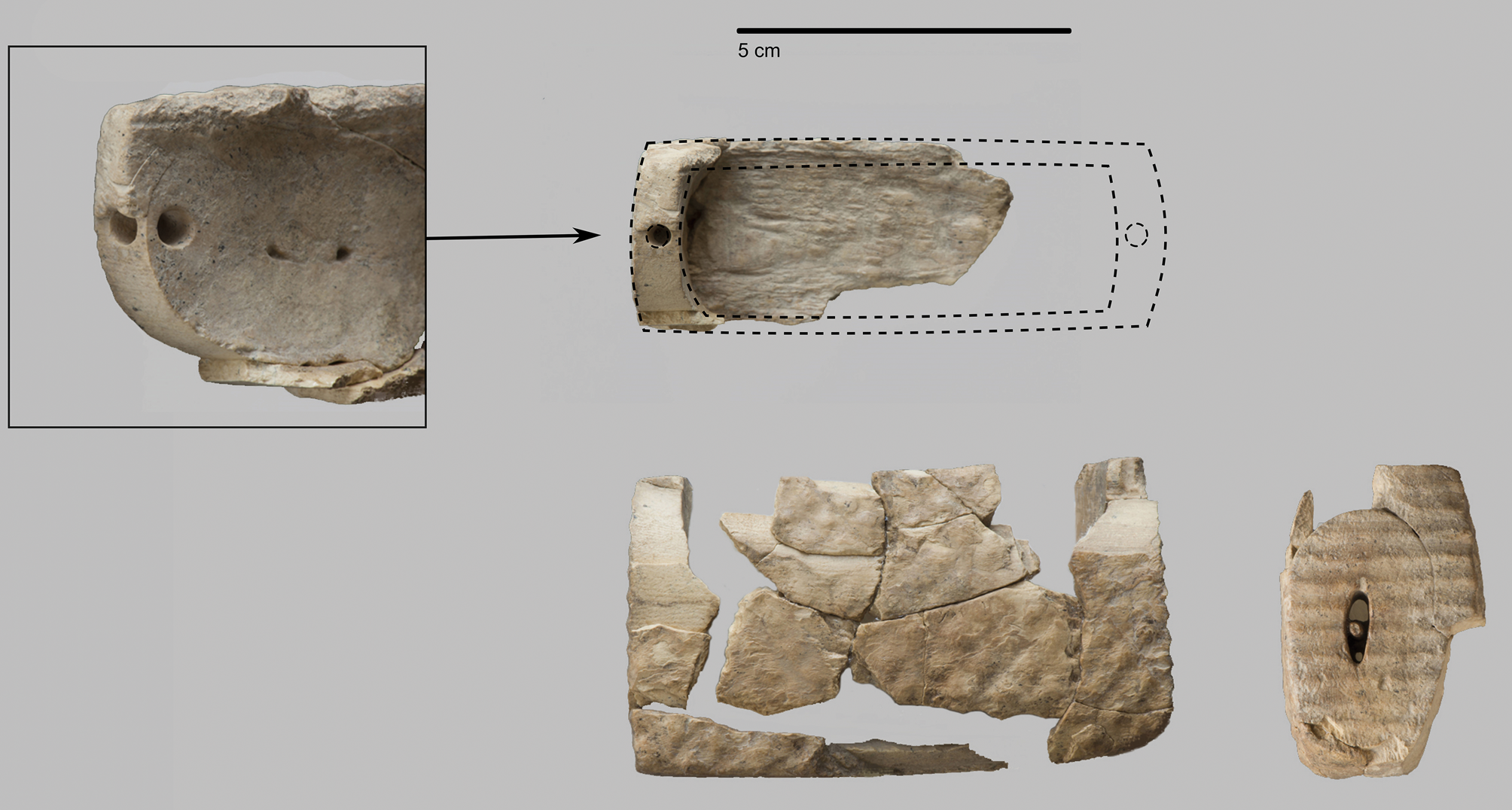

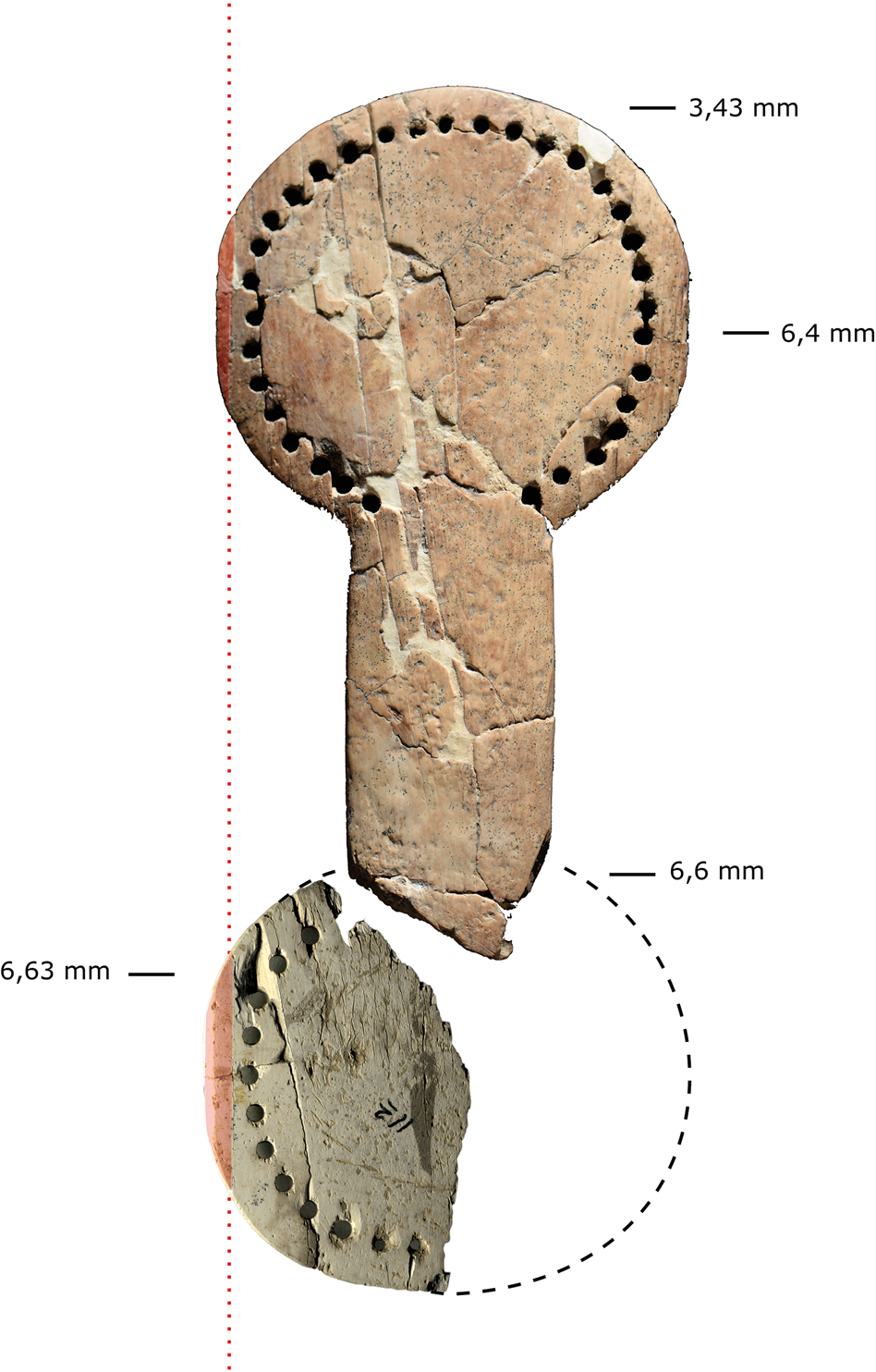

In particular, the perforated plaque fragments found in Matarrubilla and Montelirio reveal evidence to support this theory (Fig. 19):

-

(I)Their shape and the arrangement of the perforations are coincident;

-

(II)Both are made on longitudinal plates;

-

(III)Both preserve part of the cementum of the tusk in the same area;

-

(IV)The Montelirio piece increases in thickness from the perforated part to the more distal end: the thickness of the section increases from 3.13 mm to 6.6 mm, while the Matarrubilla fragment is 6.63 mm thick. Although we have not been able to refit one piece completely with the other, these clues point to the possibility that both pieces are fragments of the same object that would have been symmetrical, with two ends in the form of a circle joined by a straight shaft, which would be in this case thicker at one end (max. 6.63 mm) and thinner at the other (min. 3.13 mm).

Figure 19. Racquet-like artefact from the Large Chamber of Montelirio (upper) and from the corridor of Matarrubilla (lower). With a line and in millimetres is the thickness of the piece at the indicated height. The cementum identified in the fragments is indicated in red.

All of this echoes the words of Bollong (Reference Bollong1994) when discussing ‘category 2’ fragmentation of ceramics, whereby no physical re-fit but similarity of morphological characteristics indicates ‘sherds’ from the same area of a common vessel. In fact, the Matarrubilla plaque fragment (referred to in the bibliography as a ‘sandal-shaped idol’) has already been claimed to be older than the context in which it was found (Schuhmacher et al. Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, Dindorf, Nocete Calvo, Vargas Jiménez, García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez, Hurtado Pérez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñón Briones2013a, 498) and as we have mentioned, its unusual deposition in the corridor, and therefore outside the ‘traditional’ deposition zone (the chambers), could point in the same direction.

Furthermore, the remains of elephant tusks from these three structures could also point to an act of intentional fragmentation. The tusk segment from the Matarrubilla corridor is from Elephas (Palaeloxodon) antiquus (García Sanjuán et al. Reference Rogerio-Candelera, Karen Herrera and Millar2013, 623, table 2; Schuhmacher Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, López Padilla and Schuhmacher2012a,Reference Schuhmacherb) as would also be the case with the tusk/tusks deposited in the Small Chamber of Montelirio (Pajuelo Pando Reference Pajuelo Pando, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016). Could this be taken to mean that at some point the users of Matarrubilla fragmented the Montelirio tusk/tusks and deposited a segment in Matarrubilla?

For the time being, the impossibility of physically refitting the pieces, and the lack of more data on the raw material (such as DNA analysis), render this hypothetical. However, we believe that the aforementioned evidence may be indicative of a practice of fragmentation and redistribution of ivory objects. If we develop the implications of this hypothesis, then we could argue that there was a common practice: when a new tholos was built, a previous one was visited. Or at least, this could have happened between these three monuments for several generations. Intentional fragmentation of material culture has been widely documented in Neolithic and Copper Age Europe (Chapman Reference Chapman2000; Chapman & Gaydarska Reference Chapman and Gaydarska2007), including the specific case of Perdigões in the Iberian Peninsula, for which a practice of deliberate fragmentation of ivory lunulae has been suggested, as virtually no whole pieces (only one) were found (Valera Reference Valera2010).

Thus, the hypothetical sequence could have been as follows: around 3000–2800 bce, Structure 10.042–10.049 was built and used, in which bodies and materials were deposited during an unknown period of time. Some three generations later, Montelirio was built and used between 2800 and 2700 bce. During or/and after its construction, the users of Montelirio visited nearby Structure 10.042–10.049 and deposited some offerings, including a long-barbed arrowhead and white beads, while at the same time taking parts of older artefacts (fragments of combs and small D-section rings) from it. Subsequently, possibly between 2700 and 2600 bce, the builders of Matarrubilla, or perhaps in a later re-use of this monument itself after 2500 bce, reopened Montelirio and fragmented the plaque with perforations of the Large Chamber and one tusk of the Small Chamber to take parts of these objects to the new monument, where the deposition was made in the corridor.Therefore, the value of the ivory stemmed not only from its intrinsic value as a raw material (hardness and durability, showy white colour, and the fact that it enabled production of larger objects): time would also increase the value of some of the objects, as they gradually became relics, or heirlooms, associated to times past.

The communities that lived at and/or frequented Valencina throughout the third millennium bce developed a special relationship with ivory and certain objects made from it: ivory gained a high symbolic value (McGhee Reference McGhee1977). This resulted primarily from its very nature as an inherently exotic commodity (Helms Reference Helms1988) and from the skilled labour invested in its transformation into high-end idiosyncratic artefacts. Ivory came from distant worlds and was associated with large animals, unknown and never seen by most members of Iberian Chalcolithic societies. This simple fact probably invested the material with an aura of mystery, magic and maybe also danger in the eyes of the majority. That was probably also the case of sperm whale teeth, used in the same way as ivory in Chalcolithic Portugal, even if these animals could only be seen near the coast and as beached specimens. Their size, mysterious life in the sea and the ability to see them up close due to beaching probably conferred on them a mythical meaning, as happened in medieval and even modern times (Schuhmacher et al. Reference Schuhmacher, Banerjee, Dindorf, Sastri and Sauvage2013b). This could also explain the exchange of whale bones observed for the Magdalenian in the Pyrenean-Cantabrian region, besides the existence of technical reasons linked to their size (Lefebvre et al. Reference Lefebvre, Marín-Arroyo and Álvarez-Fernández2021). It stands to reason that, because of its exotic provenance, ivory would have endowed the persons who dealt with it, obtained it, controlled its procurement and used it with a special power and prestige (García Sanjuán et al. Reference Rogerio-Candelera, Karen Herrera and Millar2013; Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b,Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño and Cintas-Peñac; Schuhmacher Reference Schuhmacher, Bartelheim, Bueno Ramirez and Kunst2017). It is even possible that individuals or parties from southern Spain travelled to northern Africa and other regions to procure the ivory or even actually participated in expeditions to chase the elephants down. The breadth and depth of exotic material at Valencina and other southern Iberian Copper Age sites leaves little doubt that sailing must have also been an important activity at the time (for a discussion of maritime sailing in third-millennium Iberia, see Guerrero Ayuso Reference Guerrero Ayuso2010; Schubart Reference Schubart1990).Therefore, there may have been an element of agency in how ivory was sought after and procured; people like the ‘Ivory Merchant’ must have increased their prestige or rank through their association with distant lands and, perhaps, dangerous travels—sensu Helms (Reference Helms1988). But the value of ivory objects also came from their histories or biographies. Once they became ‘old’, they evoked times past and genealogical connections, bonding people, monuments, moments and places, through an enchainment relation (Chapman Reference Chapman2000; Chapman & Gaydarska Reference Chapman and Gaydarska2007). In the evolution towards early social complexity, the nature of personhood was profoundly transformed (Gilman Reference Gilman, Price and Feinman1995, 236).

In the Guadalquivir valley, ivory appears to have played a key role in this process, helping to create a new ideology of rank. It seems that in the cases discussed here, the deposition of ‘new’ elements in previous structures and the collection of parts of ‘ancient’ objects to introduce them into more modern structures was a way to legitimize social and political strategies and a means to perpetuate the union with ancestors, or with earlier prominent lineages. As happened with other selected items (Lillios Reference Lillios1999), ivory objects would have been turned into heirlooms through the fragmentation-redistribution process described above: used first to create idiosyncrasies by which would-be and/or established leaders would attempt to construct a ‘hereditary rank’, and later helping to maintain them over generations.

Conclusions

Through a detailed analysis of ivory, one of the most appealing raw materials in our past as a species, we have been able to explore how material culture was used to construct cultural identities and to support political claims to prestige and power in Copper Age Iberia. Identity is constructed but bound by the cultural repertoires to which people have access and the structural context in which they live (Lamont Reference Lamont and Turner2001, 171). The arrival of new raw materials, objects and technologies may therefore be an opportunity for social change. During the first 200 years of activity at Valencina, reflected in burial activity at the La Huera and Calle Dinamarca hypogea (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez and Cáceres Puro2018a), no foreign imports appear to have made their way into the site. Then ivory from Africa and Asia appeared rather suddenly between 3000 and 2900 bce, alongside other foreign imports such as ostrich eggshell or amber, and quickly became a raw material of outstanding social and ideological importance, not available to everyone. Our research reveals how ivory played an important role in the manufacture of social and ritual paraphernalia and in the crafting of idiosyncrasies. Not only are many of the site's most sophisticated personal ornaments made of ivory, but also containers for other substances deposited in the graves. Why choose ivory instead of wood or leather to make a lid or part of a container? It is very possible that not only the exoticism of the material but also its colour had something to do with the choice: together with red and black, white was one of the three most used colours in the symbolism of death in Late Neolithic and Copper Age Iberia (Bueno Ramírez et al. Reference Bueno Ramírez, Balbín Behrmann, Barroso Bermejo, Carrera Ramírez, Hunt Ortiz, Fernández Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016, 397). The white of the ivory would have contrasted with the red and green tones of the objects they complemented.

Ivory was not used to make utilitarian objects. It was used to create showy personal objects intended for display, attached to someone's body, as was the case with combs, bracelets, pectorals, pendants and daggers. The vessels and the ivory elements for decoration (discs with perforation) or parts of composite objects (lids and mouths of containers) may have had a more social or collective character, like ritual furniture, perhaps belonging to a community, corporate group or ceremonial centre/structure, and not to a particular individual. An example of this would be the lids and the container mouths of Montelirio.

The identity and rank of these groups or individuals would be crafted through an incipient process of exclusion (which is intrinsic to the creation of identity: e.g. Butler Reference Butler1990; Hall & Du Gay Reference Hall and Du Gay1996; Laclau & Mouffe Reference Laclau and Mouffe1984; Lamont Reference Lamont1992; Reference Lamont and Turner2001). This would have included defining the ‘I’ or ‘we’ against the ‘others’–reinforcing concepts of ‘Othering’ and ‘Otherness’ which are routinely applied in the construction of identities (e.g. Brons Reference Brons2015; Gonzalez Alvarez & Alonso Gonzalez Reference González Álvarez and Alonso González2014; Halsall Reference Halsall, Lopez Quiroga, Kazanski and Ivanisevic2017; Harland Reference Harland2017; Jensen Reference Jensen2011; Staszak Reference Staszak, Kitchin and Thrift2008).The choice of unique objects in ivory and particular decorative patterns was a means of marking the identity of small specific groups, within a broader Late Neolithic/Early Copper Age tradition that persisted throughout southern Iberia. This general Chalcolithic substrate, mainly characterized by collective burials in which grave goods usually were not related to a particular person, began slowly to disintegrate with the burial of new ‘special’ collectives or individuals, the first of whom appears to have been the ‘Ivory Merchant’. They differed from the rest of society either because of the quantity, variety and sophistication of their grave goods, or because of their unique character (i.e. individual burials with exotic grave goods). This has been interpreted as the emergence in the lower Guadalquivir River valley (between 3000 and 2600 cal. bc) of an‘elite’ for which ivory was precisely the common denominator (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Vargas Jiménez and Cáceres Puro2018b,Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez-Triviño and Cintas-Peñac; Schuhmacher Reference Schuhmacher, Bartelheim, Bueno Ramirez and Kunst2017).

In the specific social dynamics generated in the lower Guadalquivir valley at the start of the third millennium bce (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Cintas-Peña, Bartelheim, Luciañez-Triviño, Meller, Gronenborn and Risch2018b, 319), this incipient search for differentiation was not carried out abruptly. Altering or modifying living conditions always implies a risk, since only by maintaining known cultural systems is there confidence in a successful survival (Aranda Jimenez Reference Aranda Jiménez2015, 127). Accordingly, would-be leaders, as prominent social figures of the early third millennium, needed to legitimize their position through a real or fictitious kinship relationship, in which idiosyncrasies crafted in ivory played a key role. This was made by means of the possession and exhibition of sumptuous objects made of exotic materials and the visiting and worshipping of earlier monuments, especially through the fragmentation and collection of ancient ivory objects. Ivory became a vehicle for the materialization of new ideologies and power strategies—sensu DeMarrais et al. (Reference DeMarrais, Castillo and Earle1996). It can be argued that it was a time of struggle and change, but also of persistence and resistance; in the dialectical tension between differentiation and the resistance to it, ivory played an important, dual and contrasting role: it was a means of destruction of the old order because it was used to craft new identities, but at the same time, it was a vehicle of legitimation of these new roles/identities, since these individuals needed to secure their position by claiming a bond with their ancestors.

Acknowledgements

This research has been carried out thanks to two research grants—grant numbers BFI-2012-261 (Predoc) and POS-2018-1-0074 (Postdoc)—funded by the Basque Government awarded to M. Luciañez-Triviño, and has been developed within the Prehistoric Research Consolidated Group of the Basque Country University UPV/EHU (IT1223-19). We thank the staff of the Museums of Seville and Valencina, as well as all the archaeologists who have provided material and support for the study. Many thanks also to Professor Timothy Earle and Dr Marta Díaz-Guardamino Uribe for their feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.