Much has been written about the physical characteristics of Byzantine portraits, but relatively little about the philosophical background to their style and presentation. The following pages attempt to fill that gap by exploring the concepts of similarity and difference in Byzantine imperial and hagiographical portraiture in relation to Aristotelian theories of physiognomy and logic. The concluding section of the paper attempts to characterize the relationship between Byzantine art and Aristotelian philosophy with the help of a comparison between Byzantine art and the High Gothic art of the West, which has been related to Aristotelian ideas through the impact of scholasticism.

Physiognomic theory and imperial portraiture

A particularly interesting text in regard to Byzantine concepts of imperial portraiture is a late twelfth-century panegyric composed by Michael Choniates in praise of Isaak Komnenos, where the orator specifically discusses the emperor's appearance in relation to icons, in particular those of David, the model to whom Byzantine rulers were most frequently compared.Footnote 1 He says:

The emperor [that is, Isaak Komneneos] resembles David in almost all characteristics that adorn not only the soul but also the body. It is not possible to set them side by side at the present time, except insofar as one can put forward an icon of David, and by means of the icon briefly demonstrate the identity of the characteristics of the prototypes.Footnote 2

At this point Michael Choniates paraphrases the first axiom from Euclid's Elements, which states: ‘Things which are equal to the same thing are also equal to one another’.Footnote 3 But Choniates gives a different version: ‘For it is said that things which are the same as the same thing are also the same as one another’.Footnote 4 Thus the Byzantine panegyrist goes beyond the notion of equality to suggest sameness. Choniates goes on to conclude: ‘If, then, the emperor may be shown to resemble the icon of David, it is plain that the emperor must be much like David himself in every way.’Footnote 5

In the ensuing discussion, Choniates explores at some length the idea that the sameness of the physical characteristics of Isaak and David also indicates a sameness of spiritual qualities, using biblical quotations to support his postulates:

But what is the icon of David and where is it set up? It is inscribed upon the sacred tablets of the spirit. For these know how to obtain an impression of the characteristics of both the souls and the bodies of blessed men. But we should consider, how do they outline the bodily beauty of David? For it is said: ‘… David was ruddy in complexion, with beautiful eyes and good in the sight of the Lord.’ (I Samuel 16:12) And again, with the bodily they also show the spiritual [saying]: ‘And behold … the man was prudent, and warlike, and wise in speech, and a man of good appearance, and the Lord was with him.”’(I Samuel 16:18)Footnote 6

Thus Choniates claims that the common physical characteristics of David and the emperor reveal their common spiritual virtues.

The idea expressed by Choniates, that the inner character of the soul is revealed by the external characteristics of the body, had an ancient pedigree in physiognomy, going back to Aristotle himself.Footnote 7 In the Prior Analytics Aristotle had proposed that: ‘It is possible to judge men's character from their physical appearance, if one grants that body and soul change together in all natural affections.’Footnote 8 He went on to posit, by way of example, that if the sign of bravery in the class of lions is large extremities, then a brave man would also exhibit this sign.Footnote 9 Aristotle's scattered observations on physiognomy were expanded and systematized in pseudo-Aristotle, the name given to two treatises attributed to him.Footnote 10

These treatises, as well as later ones such as the second-century Physiognomy by Polemon and the fourth-century Physiognomy by Adamantius the Sophist were known and cited by the Byzantines. Thus, when Choniates refers to the ‘beautiful eyes’ of David, he may be echoing Polemon and Adamantius, who both say that ‘shining eyes’ reveal a good character.Footnote 11 There are also very close parallels between the earlier physiognomic works and an anonymous ekphrasis of the jousts of Manuel I Komnenos, which was composed in 1159, and probably described a painting of the event.Footnote 12 The author of the ekphrasis carefully describes the emperor's body from head to feet, explaining how each physical feature expresses inner virtues, which he associates specifically with David.Footnote 13 For example, he says that the imperial eyebrows are ‘not set diametrically apart from each other’, because this feature is ‘completely alien to manliness and nobility’.Footnote 14 Here he echoes Adamantius, who states that the eyebrows of a manly man are not stretched.Footnote 15 When the author of the ekphrasis claims that the emperor's chest is ‘strong, and truly the chest of a man’,Footnote 16 he echoes ps.-Aristotle, where we read that ‘a large well-articulated chest signifies strength of character, as in males’.Footnote 17 Manuel's shoulders are ‘broadly constructed, and, while heroic in form, they retain symmetry’,Footnote 18 while for ps.-Aristotle shoulder blades that are ‘broad and set apart, neither too closely nor too loosely knit’ indicate a ‘courageous man’.Footnote 19 Finally, Manuel's arms are ‘of good length … rejecting in equal measure lack of flesh and excessive fleshiness, the one as weak, the other as heavy and sluggish’.Footnote 20 This description echoes Adamantius, who says that if the arms are long, this ‘is a sign of good conduct and strength’, and that ‘those that are attenuated are unmanly, and those which are very fleshy are ignorant and insensible.’Footnote 21

A very abbreviated version of the description of Manuel I appears in the Alexiad of Anna Komnene, where, in a verbal portrait of her father, she describes ‘the breadth of his shoulders, the strength of his arms, and the development of his chest’ as features belonging to a hero.Footnote 22 Here again same physical traits as are referenced in the physiognomic texts are mustered in praise of the ideal emperor. The idea that an individual's portrayed characteristics reflect inner virtues is expressed in a fourteenth-century panegyric of Andronikos II by Nikephoros Xanthopoulos. Here too an icon of the prototype is invoked, but the model in this case is Constantine rather than David. Xanthopoulos claims that Andronikos is an exact icon of Constantine, a veritable mirror bringing to light the outward appearances of the prototype's soul.Footnote 23

In sum, ancient physiognomy provided support for the proposition that the physical characteristics that were shared by the emperors and by David and other revered models of imperial rule such as Constantine, indicated shared spiritual virtues. Choniates says that the emperor resembles David in all respects, there being no differences between them. This means that, logically, it would be impossible for imperial portraits to show individual characteristics – they all had to resemble the ideal portrait types of David or Constantine, whatever the emperor actually looked like. If we use the Aristotelian terminology of logical definitions, to which we shall turn later, the portraits of the emperors expressed their essence, that is, their Davidic or Constantinian virtues, but not the accidents of their individuality.

This ideology of sameness is reflected in the normative characteristics of imperial portraiture in Byzantine art, particularly in the effigies appearing on coins and seals, which provide the most complete and widely circulated series of ruler portraits that survives from Byzantium.Footnote 24 Several scholars have observed that the imperial portraits on medieval coins and seals are highly stylized.Footnote 25 Not only are individual emperors similar in their imperial costume, as would be expected, but in addition their facial features tend to show little differentiation, corresponding instead to standardized types. Between the eighth and the twelfth centuries two basic types of imperial portrait predominate (with some exceptions, such as the rare ‘portrait’ coins and seals from the Macedonian dynasty).Footnote 26 The earlier type is exemplified by the two copper coins in Figs 1 and 2. Fig. 1 shows a follis of Leo IV beside his son Constantine VI, which was minted between 776 and 778.Footnote 27 His son would have been aged between five and seven at the time. Fig. 2 illustrates a follis portraying Michael II and his son Theophilos, struck between 821 and 829.Footnote 28 The portraits on the two coins are extremely similar. The faces are triangular in shape; the older emperor, on the left in each case, has a short beard, the younger one, on the right, has no beard. The hair is worn above the shoulders, and bunches out at the sides. The schematic character of the portraits on the two coins is not due to the lowly material, copper, for the same phenomenon is found in gold. Fig. 3 shows Constantine VII and his son Romanos II, on a coin minted between 945 and 959.Footnote 29 The portrait types are virtually the same as those on the eighth and ninth century copper coins.

Fig. 1. Copper coin of Leo IV and Constantine VI, obverse.

Credit: author

Fig. 2. Copper coin of Michael II and Theophilos, obverse.

Credit: author

Fig. 3. Gold coin of Constantine VII and Romanos II, reverse.

Credit: Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC

Beginning in the tenth century, a second imperial portrait type emerges, as stereotyped as the first. It is seen in Fig. 4, illustrating an eleventh-century gold coin of Constantine IX Monomachos dating between 1042 and 1055,Footnote 30 and in Fig. 5, on a twelfth-century billon coin of John II Komnenos dating between 1122 and 1143.Footnote 31 In this portrait type the emperor does not have a triangular face, with a pointed chin: the chin is rounded. He has a short striated beard, and his hair is short and not bunched out at the sides. The same two imperial portrait types appear on Byzantine seals. On a seal of Basil I and his son Constantine,Footnote 32 the features are similar to those on the coin of Michael II (Figs 2 and 6). On the other hand, the portrait on a seal of Basil II conforms to the second type (Fig. 7).Footnote 33 The face is no longer triangular in outline, the chin is rounded, and the hair is short without the bunched-up locks on either side.

Fig. 4. Gold coin of Constantine IX, reverse.

Credit: author

Fig. 5. Billon coin of John II, reverse.

Credit: author

Fig. 6. Seal of Basil I and Constantine, reverse.

Credit: Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC

Fig. 7. Seal of Basil II, reverse.

Credit: Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC

The standardization of imperial portraits on coins and seals accords with the postulates of physiognomic theory, namely that unvarying physical characteristics were the expression of perennially desired traits of character exhibited by revered models such as David or Constantine; the stereotyped effigies were in a sense icons of perfection that supplanted the physical particularities of individual emperors. It may be noted that the two common imperial portrait types that we have described do indeed exhibit features resembling two of the standard portrait types of David in his maturity appearing in post-iconoclastic art. For example, in the depiction of David enthroned as king on the opening folio of the ninth-century Chludov Psalter, he has a triangular face, a short beard, and hair that bunches out at the sides,Footnote 34 while in the eleventh-century mosaic of the Anastasis at Hosios Loukas David displays the rounded chin and short striated beard characteristic of the second type of imperial effigy (Fig. 8; compare Figs 4 and 5).Footnote 35

Fig. 8. Hosios Loukas, Katholikon, mosaic, Anastasis. Detail of David and Solomon.

Credit: Photo by Josephine Powell, photograph courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University.

Hagiographical portraiture and Aristotelian logic

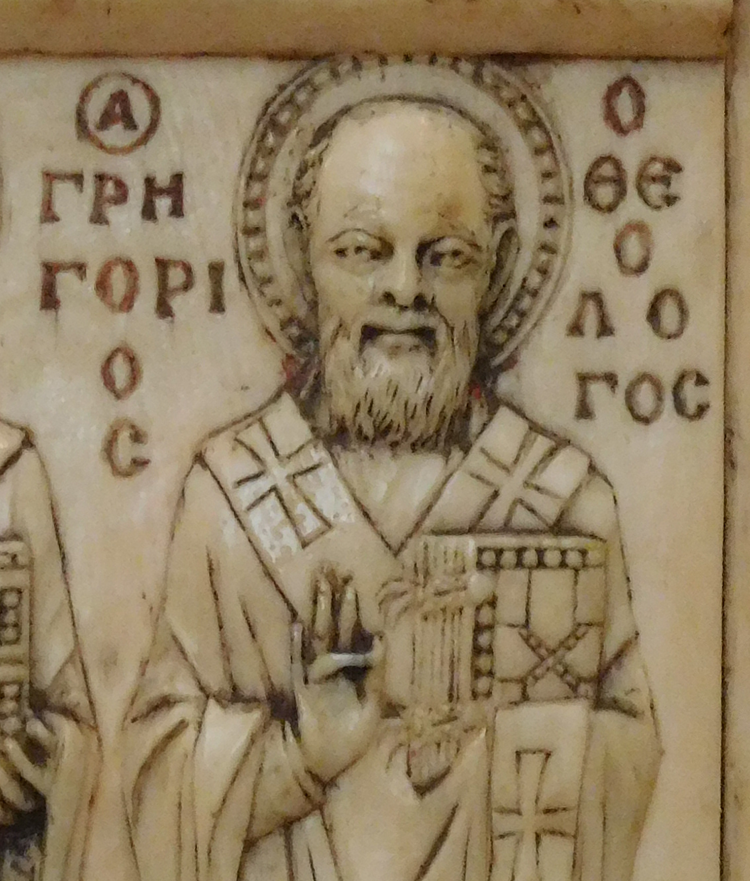

Descriptions of the physical appearances of saints in Byzantine literature express an ideology different from that found in verbal portrayals of emperors. Here we find a tension between particularity, for the purpose of identification of an individual saint, and similarity, for the purpose of encomium. Since saints, unlike most emperors, were venerated in their own right as individuals with special supernatural powers, and thus needed to be recognizable by their supplicants, their differentiation was important, a point to which we shall return in the conclusion.Footnote 36 Instances of tension between the two contradictory aims, sameness and distinctness, can be found in the genre of Eikonismos, which provided a thumbnail delineation of an individual resembling the brief bodily descriptions that a modern novelist will typically make upon introducing new characters into the narration.Footnote 37 A well-known example of eikonismos is the group of short descriptions in the ninth or tenth-century history attributed to Oulpios the Roman.Footnote 38 Oulpios described Adam and the Old Testament prophets, Peter and Paul, various church fathers, and two iconophile patriarchs of Constantinople. The purpose of his descriptions is unclear. It has been said that they did not serve as practical guides for artists,Footnote 39 but some of them are remarkably close to the portrait types appearing in art, especially in the case of the church Fathers. For an example, one can compare his account of Gregory of Nazianzos with the portrait of the saint in the Harbaville Triptych, a tenth-century ivory now in the Louvre (Fig. 17).Footnote 40 Oulpios says, in part, that the saint had a ‘gentle and kindly appearance, although one of his eyes, namely the right one, was rather sullen in appearance, since a scar had contracted it in the corner; beard not long, but fairly thick, bald, white-haired, the tip of his beard having a smoky appearance’.Footnote 41 Apart from the colouring, these features, the baldness, the full medium-length beard, and even the contraction of the right eye all can be seen in the ivory.

When he comes to describe the two patriarchs, Oulpios says that they resemble in their appearance older and more venerated church Fathers, but he is at the same time careful to point out the differences. Thus, of Tarasios he says: ‘Our father Saint Tarasios was in bodily character similar to Gregory Theologos [of Nazianzos], apart from the latter's grey hair and injured eye, for he was not completely grey’.Footnote 42 In the case of these portraits of more recent saints, one can detect a conflict between two different demands: to depict the physical accidents of the individual, and to show the essential qualities of his nature. In order to demonstrate that he shared the spiritual virtues of Gregory of Nazianzos, Tarasios was portrayed as similar to him, but at the same time distinguished as an individual from his model. As noted above, in Byzantium images of saints were, in theory, required to be individually recognizable by those who supplicated them, unlike the portraits of emperors, who were only rarely the objects of cult.

In artistic practice, portraiture of the major saints tended to emphasize particularity rather than similarity. If the portraits of the emperors on Byzantine seals can often be seen as abstract and stereotyped, this was not true of the saints, whose sigillographic portraits were highly individualized. An example is provided by a tenth-century seal bearing a fine image of John the Baptist (Fig. 9).Footnote 43 The saint has a long face, a long pointed beard, and long locks of hair that flow down his shoulders. There is also a little curled wisp of hair at the center of his forehead. All these features characterized the standard portrait of John the Baptist known in Byzantine art since the sixth century. The same portrait type can be seen, for example, in the representation of the saint in the Harbaville Triptych (Fig. 18).Footnote 44 Even the wisp of hair on the forehead is there.

Fig. 9. Seal of Theodotos protospatharios, obverse. St. John the Baptist.

Credit: Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC

For a contrast with John the Baptist we can turn to George, whose well preserved portrait is displayed on a seal of the eleventh century (Fig. 10).Footnote 45 In this case the saint has no beard, and his hair is full and curly. His facial type too can be traced back to the period before iconoclasm, when we find it among the seventh-century mosaics of St Demetrios in Thessaloniki.Footnote 46 In the earlier work the saint wears a military cloak, while on the seal his inclusion among the warrior saints is shown by his spear, his shield, and his cuirass. Another military saint who is depicted on seals is Theodore. In the ninth-century specimen illustrated in Fig. 11 one can still recognize the saint's distinctive thick and pointed beard, even though the impression is worn.Footnote 47 This portrait type too had precedents in pre-iconoclastic art, as shown by a sixth or seventh century icon of Theodore at Mount Sinai.Footnote 48

Fig. 10. Seal of John Komnenos, obverse. St. George.

Credit: Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC

Fig. 11. Seal of Archbishop Euphemianos, obverse. St. Theodore.

Credit: Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC

As with the soldiers, bishops are distinguished from other classes of saints on the seals by their costumes, in their case by the wearing of stoles. In addition, each individual bishop is differentiated form the others by his facial features. St Nicholas, for example, is from the tenth century consistently characterized by short hair and a short, rounded beard,Footnote 49 while John Chrysostom has a narrow chin, narrow cheeks and a pointed beard.Footnote 50 On the seals, therefore, as in works in other media, the saints are distinguished from each other by their costumes, which divide them into classes such as soldiers with their armour, or bishops with their stoles, and also by their facial portraits, which identify them as individuals such as George or Theodore or Nicholas.Footnote 51 On the other hand, as seen above, the emperors appearing on seals are identified as belonging to the class of rulers by their regalia, but, unlike the saints, their facial portraits generally are not individualized.

In coinage, we can observe the same contrast on a rare nomisma of the Emperor Alexander, dated 912 to 913 (Fig. 12).Footnote 52 The reverse shows Alexander being crowned by John the Baptist, thus making a visual association between the baptism of Christ in the Jordan and the anointing of the emperor. It is noteworthy that in the coin the emperor has the usual schematic features of a triangular face and hair that bunches out at the sides, while John appears with his individual portrait type. The saint has a long face, a long beard, long hair that flows over his shoulder, and a wisp of hair at the top of his forehead. There is no inscription naming John the Baptist, but it is easy to recognize him from his portrait. In the case of the emperor, however, we would have no means of identifying him as an individual were it not for the legend ‘Alexander’ beside him.

Fig. 12. Gold coin of Alexander, reverse. St. John the Baptist crowning the emperor.

Credit: Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC

One further aspect of portraiture in Byzantine art should be mentioned, and that is the role played by bodily characteristics such as emaciation or bulkiness. Certain classes of saints, such as monks, and bishops tended to be shown as ascetics, thin and deprived of flesh. Other classes were shown with greater corporality. Apostles and Evangelists, the witnesses to the incarnation, were swathed in bulky antique garments, while soldiers appeared as robust, or in some cases even corpulent, the better to fight.Footnote 53

In sum, in Byzantine hagiographic portraiture, each class of individuals, soldier saints, bishops, and so forth, was distinguished in the first place by the costume, and secondly by the bodily type that was an essential feature of the class. Thus, soldiers wear military attire, may carry armour, and are robust, while bishops wear stoles and are attenuated. In addition, from the sixth century, and increasingly thereafter, the major saints within each class were differentiated by their distinct facial features and hairstyles.

The structure of Byzantine portraiture that has been outlined here with the help of coins and seals can also be described in the terminology of Aristotelian logic. In his Categories and his On Interpretation, Aristotle states that if we take the species of man, we can say that the species of man belongs to the genus of animal. Thus it is correct, for example, to say that ‘rational animal’ is an essential predication of man. Therefore, if we take an individual man such as Socrates, we can make the essential predication ‘rational animal’ of him also. But, in addition, we can make a non-essential, accidental predication of Socrates, such as that ‘Socrates is pale’. This accident, of pallor, may be predicated of other individuals, but it is not common to all men, and thus it is not part of the human essence of Socrates.Footnote 54

Later followers and commentators on Aristotle elaborated upon these basic concepts. Porphyry, in his Isagoge, lists five terms, namely genus, species, difference, property, and accident, giving several definitions for each.Footnote 55 Genus, for instance, can mean a plurality of several species. An example of a genus would be ‘animal’. Species is defined by Porphyry as a subdivision under genus, so that man, for example, is a species of animal. Differences, he says, create the division of genera into species, but any given difference is not necessarily unique to a species. Thus rationality in man is an essential property that makes him a separate species of animal, but gods also are rational. Man is separated from the gods by being mortal. A property, according to Porphyry, is an accident of a species. Some properties he describes as being ‘alone, and all, and always’,Footnote 56 giving as an example neighing for a horse. Apart from horses, no other species neighs. Finally, in his discussion of accidents, Porphyry says that they can be divided into two: separable accidents, such as sleeping, and inseparable accidents, such as blackness for ravens. Inseparable accidents of individuals include being hook-nosed or snub-nosed, having blue eyes, or having a scar from a wound.

In later centuries Byzantine writers echoed the definitions provided by Porphyry. For instance, in his Dialectica John of Damascus provides a definition of definition itself. He begins by saying that ‘a sound definition has neither a deficiency nor a superfluity of words’. As an example, he proposes that the perfect definition of man would be ‘a living being that is mortal and has reason’. He goes on to argue that if one were to add the phrase ‘and is a grammarian’ to this definition, it would exclude too many realities (that is, categories of men), because not all men are grammarians. On the other hand, if one were to omit the words ‘that is mortal’, then the definition would include too many categories, for among the beings that have reason one can include the angels as well as men.Footnote 57 Thus John of Damascus repeats Aristotle's and Porphyry's arguments, simply substituting angels for gods.

Aristotelian logic continued to be important in the Byzantine educational curriculum, becoming an important weapon in the arsenal of the defenders of images during Iconoclasm.Footnote 58 Its survival is exemplified by a handbook dating between the mid-eight and the late ninth century, which is preserved in a manuscript in the Vatopedi monastery on Mount Athos.Footnote 59 This text is deeply indebted to Porphyry's Isagoge, both in its concepts and in its vocabulary. The author repeats the five terms defined by Porphyry. Like Porphyry, he gives three meanings for genus, and in his discussion of species, he has this to say: ‘Species is predicated of Peter, and Paul, and John.… for they share in their species. Species is what is immediately ranked under genus, for individuals also are ranked under genus, but through the intermediary of the species’.Footnote 60 Concerning difference, the medieval handbook borrows from Porphyry's definitions, saying for example: ‘Difference is such as rational … for man’.Footnote 61 The handbook quotes Porphyry again in its fourth definition of property, which is that: ‘this is all, and alone, and always … such as … neighing for a horse’,Footnote 62 meaning again that only horses will neigh. Finally, in its definition of accident the handbook repeats Porphyry almost word for word, giving as examples of inseparable accidents ‘snub-nosed, hook-nosed, and blue eyed’.Footnote 63

Putting all the texts together, we could use a similar system of logical definitions to describe the structure of Byzantine portraiture.Footnote 64 Thus, in analysing portraits in Byzantine art, we could describe saints in general as a genus, divided into different species, such as soldiers or bishops. In the artistic portraits we could distinguish differences such as the non-unique essential properties of being bulky in the case of soldiers, or emaciated in the case of bishops. These differences would not be unique to any one species, as Porphyry explains, because monks as well as bishops are emaciated, while apostles as well as soldiers are bulky. Furthermore, we could propose that some essential properties are unique to particular classes of saint, or, in the words of Porphyry and the medieval handbook: ‘all, alone, and always … as in the neighing of a horse’. An example would be stoles, which are unique to bishops. Finally, under accidents, we could include non-essential particularities of individual saints, including the scars and nose shapes referred to in the logical texts, as well as the hairstyles and shapes of beards found in portraits in art. In the case of emperors, we could say that their facial portraits tend to exhibit an essential feature of their class, that is, a sameness with revered models, rather than their non-essential differences.

The relationship of art to philosophy in Byzantium and the medieval West

It can be proposed, therefore, that the logic of the presentation of saints’ portraits in Byzantine art was similar to the logic of definitions in philosophy. But how far did the relationship between philosophy and art extend? Was it only a case of two parallel structures, one controlling a sequence of logical definitions, and the other the presentation of images, or were the very forms of the images themselves intertwined with philosophical thought? One way to approach this difficult question is to examine the social contexts of the viewing of portraits, both in Byzantium and in the medieval West, where historians have likewise attempted to relate artistic production to Aristotelian logic. In Byzantium the demands made upon images in daily life played an important role in creating the distinction between icons of saints, which showed individual particularities, and portraits of the emperor, which did not. The portraits of the saints were venerated, and consequently needed to be recognizable in order to establish their identity with their prototypes, but this was not usually the case with emperors.

Through their knowledge of the saints’ portraits on their icons, the Byzantines were able to identify individual saints in the painted decorations of churches and panels – visual recognition was particularly important if they could not read the legends written beside the images. One of the many stories that illustrate this expectation is found in a sermon on the Annunciation by Leo, a mid-ninth-century archbishop of Thessaloniki. According to Leo, the Virgin and St Demetrios appeared to a young Jewish woman by night. Since she was not a Christian, she did not recognize the two saints. Afterwards, she went into a baptistery where there were several images, and was able to single out the icons of the two saints she had seen owing, as Leo says, to their ‘distinct characteristics’.Footnote 65 Unlike the saints, however, most emperors were not the objects of cult. They were not generally expected to work miracles; they were not conceived of as saints.Footnote 66 Hence there was no need to represent them on coins and seals as recognizable individuals to whom prayers might be addressed. Rather, the images of emperors expressed their essential qualities through their relationship of similarity with revered prototypes.

With respect to Western Europe, a key study is Erwin Panofsky's book Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism.Footnote 67 In this famous work Panofsky set out to explain High Gothic art and architecture with reference to scholastic thought, including ‘the assimilation of Aristotelian logic’. Panofsky claimed that such concepts as ‘universals versus particulars naturally were reflected in the representational arts’, and that ‘the High Gothic statues of Reims and Amiens, Strasbourg and Naumburg … proclaim the victory of Aristotelianism’. He argued that Gothic architects would have had some knowledge of scholastic argumentation, and repeatedly termed the relationship between architecture and scholasticism a ‘mental habit’, and a ‘modus operandi’.Footnote 68

One can take as an illustration of Panofsky's thesis the sculptures of the central west portal of Amiens Cathedral, which were created in the second quarter of the thirteenth century (Fig. 13).Footnote 69 Here there is a Last Judgment surrounded by an array of figures divided into classes, or species, which are arranged around the central portrayal of Christ in the tympanum over the door. Thus the saved souls are ordered on the left-hand side of the tympanum and lintel, and the damned souls on the right. Angels in prayer appear in the inner order of voussoirs around the tympanum, then angels holding blessed souls in the second order, martyrs holding palms in the third, confessors in the fourth, Virgins in the fifth, and finally the Elders of the Apocalypse in the outermost order. On the vault over the porch there are two more bands containing figures, the ancestors of Christ filling the inner band, and Old Testament patriarchs occupying the outer one. On the jambs we find statues of the Apostles (Figs 14 and 15), and on the embrasures beneath them personifications of the virtues and the vices. Within some of these classes, the individual members are distinguished by particular details, or accidents. Each of the Elders of the Apocalypse, for example, holds a different musical instrument, while the damned are portrayed according to their sins.

Fig. 13. Amiens Cathedral, central west portal. The Last Judgment.

Credit: author

Fig. 14. Amiens Cathedral, central west portal. Detail of apostles on left side.

Credit: author

Fig. 15. Amiens Cathedral, central west portal. Detail of apostles on right side.

Credit: author

In the case of the statues of the apostles on the jambs, we may note that only three of them are characterized by their portrait types, namely Saints Peter and Paul, who stand closest to the door on each side, and St John, who stands third in the line after Peter on the right. As in Byzantine art, Peter has short curly hair and a curly beard, while Paul is balding and has a somewhat longer beard. St John is shown as a younger man, without a beard. It is not possible to recognize the other apostles by their facial features; for example, there is very similar treatment of the hair and beards of the five apostles behind St. Paul on the left (Fig. 14). On the other hand, we can identify several of the apostles by the attributes that they hold. Thus James, second in the line after Peter on the right jamb of the door, wears a pilgrim's bag under his lowered left hand, which is adorned with shells, the emblem of this saint (Fig. 15). St Andrew, standing to the left of him, holds the cross on which he was crucified. On the other side of the door, James the Less holds a club, the supposed instrument of his martyrdom (Fig. 14).Footnote 70

In spite of their smaller scale and earlier date, the great Byzantine ivory triptychs of the tenth century provide an instructive comparison with the sculptures at Amiens: beneath a surface resemblance, they clearly display the differing attitudes toward sacred portraiture that prevailed in East and West. In the case of the Harbaville Triptych in Paris, for example, the front displays Christ enthroned at the top, surrounded by a gallery of his saints, who appear on the central panel and on each face of the two wings (Fig. 16). The saints on the ivory are divided into classes by their clothing and their attributes. Thus the apostles, wearing the ancient tunic and himation, stand immediately beneath Christ, while on the insides of the wings we find soldiers, either attired in cloaks and holding martyrs’ crosses in the lower register, or wearing armor and bearing weapons in the upper register. The bishops occupy the fronts of the wings, four above and two below, dressed in their vestments and holding books (Fig. 17). At Amiens attributes were used to distinguish individual saints, but on the Byzantine ivory the attributes are essential properties common to all members of a class, such as the stoles, which are worn by all of the bishops. On the triptych, as in other Byzantine works of art, it is the facial features that differentiate the individuals.

Fig. 16. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Harbaville Triptych with wings open.

Credit: author

Fig. 17. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Harbaville Triptych. Detail of St Gregory of Nazianzios.

Credit: author

Although the Byzantine system of hagiographic portraiture was not yet fully developed at the time that the Harbaville Triptych was carved, many of the individuals, as we have seen, are already recognizable by their particular physiognomies. There is John the Baptist, with his shoulder-length hair, long pointed beard, and the two wisps at the top of his forehead (Fig. 18). Among the bishops, we can pick out John Chrysostom, with his domed bald head and his narrow chin, as well as Gregory of Nazianzos, with his bald pate and thick squared off beard (Fig. 17). St George, with his mop of hair and beardless face, is identifiable among the solders (fig. 16, upper right). We can also see the two Theodores who succeeded the single saint of earlier times, namely Theodore Tyron, or the Recruit, and Theodore Stratelates, or the General, both with copious pointed beards (Fig. 19). These two related characters, in spite of their general similarity, were consistently distinguished from each other in their detailed characteristics.Footnote 71 For example, the coiffure of the general, on the right, was longer, while the recruit's hair was cut shorter, so as to expose his ears. The carver of the ivory has taken particular care to emphasize this particular difference between the two namesakes by enlarging Theodore Tyron's ears, which resemble those of a leprechaun (Fig. 19).

Fig. 18. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Harbaville Triptych. Detail of St. John the Baptist.

Credit: author

Fig. 19. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Harbaville Triptych. Detail of SS. Theodore Tyron and Theodore Stratelates.

Credit: author

We can speak, therefore, of parallel structures that ordered the images both in High Gothic portals and in Byzantine triptychs; in each case we find different species with essential features in common that are subdivided into particulars, that is, into individuals possessing non-essential accidents, namely attributes at Amiens, and facial features in the triptych. Both in Gothic sculpture and in Byzantine ivories, the system may be compared with Aristotelian logic, the relevance of which was kept alive by scholasticism in the West and by the debates over iconoclasm in the East. But even if the underlying structures were the same in the West and in the East, in each place the artistic expression of them took a different form. Some exceptions notwithstanding, in general High Gothic artists did not identify individual members of a class by the accidental features of their faces, preferring to distinguish them through their attributes.Footnote 72 Byzantine artists, on the other hand, preferred to differentiate saintly individuals through their physiognomies, and tended to use attributes to express the shared features of the members of a class. The reasons for this contrast between artistic practice in West and East can be found in differing conceptions of the image. As we have seen, for the Byzantines, more than for worshippers in the West, sacred images were the focus of veneration. The individualization of facial features enabled a more personal relationship between the supplicant and the saint. An attribute was more abstract – it was a metonymical sign of someone rather than a portrait. The attribute of a western saint acted as an identifier of the saint and as a reminder of a story. The defined facial appearance of a Byzantine saint, on the other hand, enabled a more intimate confrontation between the viewer and the individual represented. The worshipper could engage with a real presence. However abstract the logic that underlies the structure of Byzantine art, it was this expression of the individual person that gave it social life.

In both eastern and western portraiture the logic behind the presentation of the classes can be described in Aristotelian terms. This observation suggests that academic schools and artistic workshops alike shared in a common culture characterized by similar habits of thought, even though the one arena of expertise may not have had a direct technical knowledge of the other. However, it was the social rather than the intellectual context, and above all the viewer's engagement with the image, that directed the particular forms taken by the portraits. We might say that portraiture in medieval art was based upon need. Even in Byzantium some classes of holy figure played a larger part in individual devotion than others – saints more than prophets, for example – and therefore they were more closely and more consistently defined through their facial features.Footnote 73 Emperors, for the most part, were not venerated at all, and hence they did not have worshippers who required them to be defined by individual portraits. For them, it mattered more that their portraits displayed the unchanging essence of virtue associated with revered models such as David and Constantine.

Henry Maguire is Emeritus Professor of the History of Art at Johns Hopkins University. He has also taught at Harvard and the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and was sometime Director of Byzantine Studies at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington.