No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

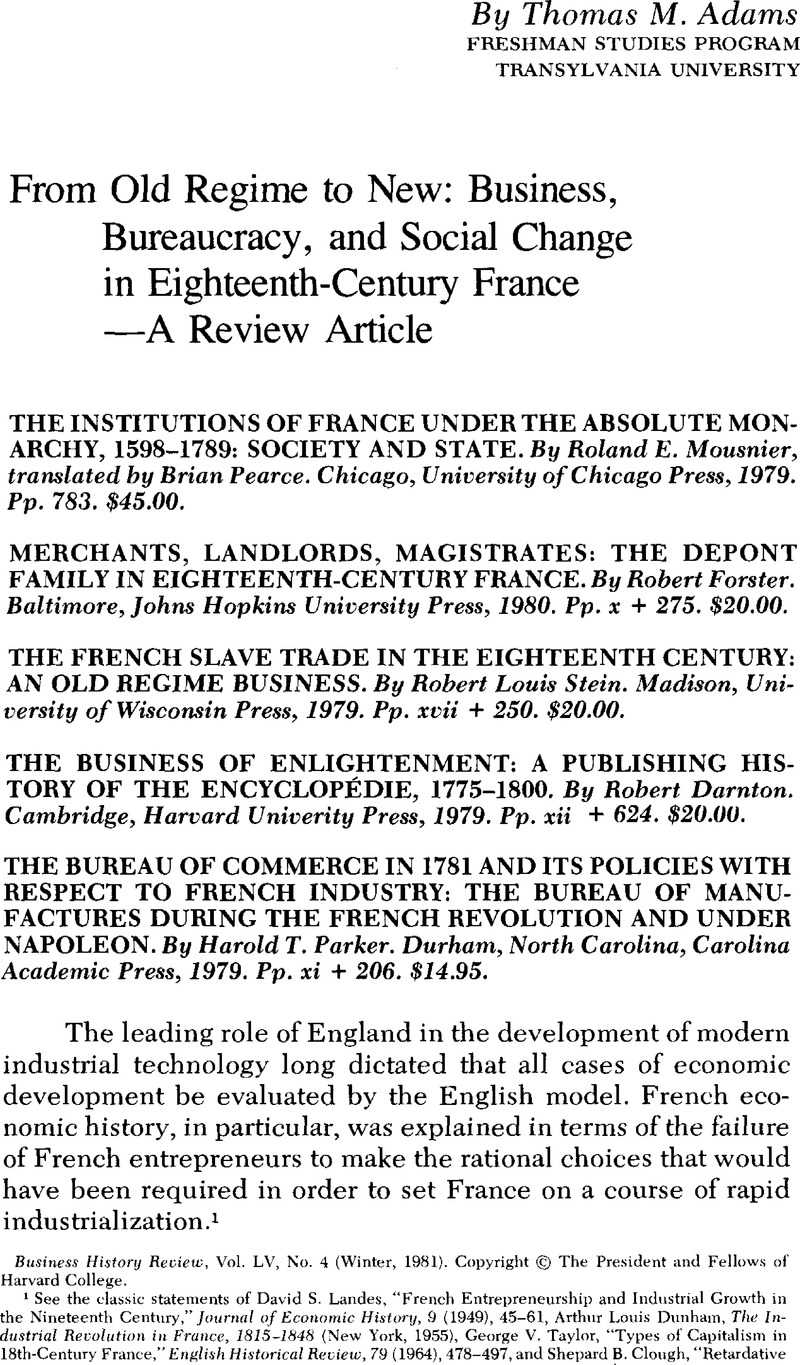

From Old Regime to New: Business, Bureaucracy, and Social Change in Eighteenth-Century France

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 June 2012

Abstract

- Type

- A Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The President and Fellows of Harvard College 1981

References

1 See the classic statements of Landes, David S., “French Entrepreneurship and Industrial Growth in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Economic History, 9 (1949), 45–61CrossRefGoogle Scholar, Dunham, Arthur Louis, The Industrial Revolution in France, 1815–1848 (New York, 1955)Google Scholar, Taylor, George V., “Types of Capitalism in 18th-century France,” English Historical Review, 79 (1964), 478–497CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and Clough, Shepard B., “Retardative Factors in French Economic Growth at the end of the Ancien Régime and during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods,” in Kooy, Marcelle (ed.), Studies in Economics and Economic History: Essays in Honour of Professor H. M. Robertson (Durham, North Carolina, 1972), 187–211.Google Scholar

2 O'Brien, Patrick and Keyder, Caglar, Economic Growth in Britain and France 1780–1914: Two Paths to the Twentieth Century (London, 1978), 68, 75, 90, 169, 196Google Scholar; perhaps the most significant statement of the need to reexamine prevailing assumptions on the subject was that of Crouzet, François, “Angleterre et France au XVIIIe siècle: essai d'analyse comparée de deux croissances économiques,” Annales. E.S.C. 21:2 (March-April 1966), 254–291Google Scholar, based in part on new data on the French economy assembled by J. Marczewski and J. C. Toutain. For a recent polemic occasioned by the writings of Lance E. Davis and Douglass North. see Leet, Don R. and Shaw, John A., “French Economic Stagnation, 1700–1960: Old Economic History Revisited,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 8, No. 3 (Winter 1978), 531–544.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

3 Roehl, Richard, “French Industrialization: A Reconsideration,” Explorations in Economic History, 13 (1976), 233–281CrossRefGoogle Scholar (including an excellent bibliography and comments on the literature); for Alexander Gerschenkron's role in promoting the newer position, see his Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective: A Book of Essays (Cambridge, Mass., 1962), 41, 69, and 353–364. Some writers retain a more or less pejorative view of French economic stagnation, but are unhappy with explanations based upon entrepreneurship or strictly technological factors. See, for example, Kemp, Tom, “Structural Factors in the Retardation of French Economic Growth,” Kyklos 15 (1962), 325–350CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and his Economic Forces in French History (London, 1971). The debate has continued in the pages of the Cambridge Economic History of Europe, as noted by Rimlinger, Gaston V., “Production Factors in Economic Development: a Review Article,” Business History Review, 54, No. 1 (Spring 1980), 109.Google Scholar

4 Sewell's work was published by the Cambridge University Press, 1980. See especially Chapter 7, “Industrial Society.”

5 David Landes sounded an appropriate warning against value judgments that historically “furnished the moral sanction for economic retardation” in the minds of chauvinistic French observers in his “Technological Change and Development in Western Europe, 1750–1914,” Chapter V in The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, Vol. VI, The Industrial Revolution and After, Part I (Cambridge, England, 1965), 598.

6 Betty Behrens adopts Mousnier's concept of the “Société d'Ordres” in her chapter on “Government and Society” in The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, Vol. V, The Economic Organization of Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, England, 1977), 549–620; Albert Soboul argues that the concept of a “society of orders” may be subsumed within a more inclusive theory of class conflict. See his article, “À la Lumière de la Revolution française; problème paysan et révolution bourgeoise,” in Hinrichs, Ernst, Schmitt, Eberhard, and Vierhaus, Rudolf, eds., Vom Ancien Régime zur Französischen Revolution: Forschungen und Perspektiven, Veröffentlichungen des Max-Planck-Instituts für Geschichte; 55 (Göttingen, 1978), 569–587.Google Scholar

7 Mousnier, Institutions of France under the Absolute Monarchy, 238.

8 Ibid., 189.

9 Ibid., 259; O'Brien and Keyder, Economic Growth, 164–165 and 193–194.

10 O'Brien and Keyder, Economic Growth, 119 and 165.

11 Mousnier, Institutions of France under the Absolute Monarchy, 473.

12 See O'Brien and Keyder, Economic Growth, 132–133 on the cohesive character on the French peasant community. The “backwardness” of French rural civilization in the late nineteenth century is carefully specified in Weber, Eugen, Peasants Into Frenchmen: the Modernization of Rural France, 1870–1914 (Stanford, California, 1976).Google Scholar

13 See Jacques Godechot, “Aux origines du régime représentatif en France: des conseil politiques languedociens aux conseils municipaux de l'époque revolutionnarie,” in Hinrichs et al., Vom Ancien Régime, 11–23; Ladurie, Emmanuel Le Roy, “De la crise ultime à la vraie croissance,” in Histoire de la France rurale, Duby, George and Wallon, Armand, general editors, Vol. 2, Vage classique, 1340–1789 (Paris, 1975), 400.Google Scholar

14 Mousnier, Institutions of France under the Absolute Monarchy, 633–636 and 674.

15 David Bien, “The Secrétaires du Roi: Absolutism, Corps, and Privilege under the Ancien Régime,” in Hinrichs et al., Vom Ancien Régime, 153–168; see also Temple, Nora, “The Control and Exploitation of French Towns during the Ancien Régime,” History, 51 (1966), 16–45.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

16 Bordes, Maurice, “La Réforme municipale du contrôleur général Laverdy et son application dans certaines provinces,” Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine, 12 (October-December 1965), 241–270.Google Scholar

17 For an excellent analysis of the realignment of elites and the political context, see Lucas, Colin, “Nobles, bourgeois and the origins of the French Revolution,” Past and Present, 60 (August 1973), 84–126.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

18 Forster, Merchants, Landlords, Magistrates, 63; the term “decapitation,” Forster notes, was first used in this sense by Hauser, Henri, “French Economic History, 1500–1750,” Economic History Review, 4 (1933), 257ff.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

19 Forster, Merchants, Landlords, Magistrates, 94; Forster develops a similar point with other evidence in “Seigneurs and their Agents,” in Hinrichs et al., Vom Ancien Régime, 169–187.

20 Forster, Merchants, Landlords, Magistrates, 74.

21 Ibid., 27, 34, and 133.

22 See the recent study of Wick, Daniel L., “The Court Nobility and the French Revolution: the Example of the Society of Thirty,” Eighteenth-Century Studies, 13, No. 3 (Spring 1980), 263–284.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

23 Forster, Merchants, Landlords, Magistrates, 190; Forster's documentation provides a guide to the scholarly acceptance of Charles-François Depont's identity as the correspondent to whom Burke referred in his Reflections.

24 Ibid., 192; see also, Colin Lucas, “Nobles, bourgeois and the origins of the French Revolution,” 125.

25 Forster, Merchants, Landlords, Magistrates, 205, 222–224, and 228.

26 Ibid., 231.

27 Ibid., 225; this movement might be construed as an instance of the “process of pastoralization” that affected the West, according to David Landes (citing Crouzet), in “Technological Change,” 372.

28 Sartre, Jean-Paul, La Nausée (Paris, 1938), 118–136.Google Scholar

29 Stein, French Slave Trade, 201; this study fills a place between the broader statistical study of Curtin, Philip D., The Atlantic Slave Trade: a Census (Madison, Wisconsin, 1969)Google Scholar and the social and commercial study of Meyer, Jean, L'armement nantais dans la deuxième moitié du XVIIIe siècle (Paris, 1969).Google Scholar

30 Stein, French Slave Trade, 187; Stein also notes that the re-export of tropical products provided France with trade surpluses (p. 197).

31 Ibid., 32.

32 Ibid., 197; Clark, John G., “Marine Insurance in Eighteenth-Century La Rochelle,” French Historical Studies, 10, No. 4 (Fall 1978), 572–598.CrossRefGoogle Scholar Stein (p. 178) cites Jean Meyer's important chapter on book-keeping methods. Meyer places more emphasis on the unwieldiness of the slavers' books and the backwardness of their methods (Armateurs, 129). Stein, who also worked directly with the books, was more impressed by their completeness.

33 Stein, French Slave Trade, 188; Roche, Daniel, Le Siècle des lumières en province: académies et académiciens provinciaux, 1680–1789, 2 Vols. (Paris, 1978), I, 249–253Google Scholar; Stein also discusses the limited ethical perceptions which allowed the traders to view the slaves only as perishable commodities (p. 193 and 196); Forster notes (p. 23) that the slaves who died on Paul Depont's ships did not trouble the conscience of his son, who was anxious however to restore the product of his father's usury.

34 Stein, French Slave Trade, 199.

35 The foregoing details from Panckoucke's early life are drawn from Tucoo-Chala, Suzanne, Charles-Joseph Panckoucke et la librairie française, 1736–1798 (Pau and Paris, 1977), 48, 55, 68–69, 91Google Scholar; I am grateful to Professor Jeremy Popkin of the University of Kentucky for this reference; see his review article, “The French Revolutionary Press: New Findings and New Perspectives,” Eighteenth-Century Life, 5, No. 4 (Summer 1979), 90–104; see also Levy, Darline Gay, The Ideas and Careers of Simon-Nicolas-Henri Linguet:a Study in Eighteenth Century Politics (Urbana, Illinois, 1980), 111Google Scholar, on Panckoucke's promotion of journalism.

36 Darnton, Business of Enlightenment, 53.

37 Ibid., 66.

38 Robert Damton has described this milieu in “The World of the Underground Booksellers in the Old Regime,” Hinrichs et al., Vom Ancien Régime, 439–478.

39 Darnton, Business of Enlightenment, 203–245, vividly reconstructs and interprets the culture of the independent artisans and their relationships with their employers.

40 Ibid., 286; Roche, Académies, I, 280.

41 Darnton, Business of Enlightenment, 453.

42 Ibid., 433, 436, 439, 476; Daniel Roche explores this problem as it applies to members of the academies of the Old Régime in “Personnel culturel et représentation politique de la fin de l'ancien Régime aux premières années de la Révolution,” in Hinrichs et al., Vom Ancien Régime, 502.

43 Parker, 97. Parker first stated a similar position in “French Administrators and French Scientists during the Old Régime and the Early Years of the French Revolution,” in Ideas and History: Essays presented to Louis Gottschalk by his Former Students, ed. by Parker, Harold T. and Herr, Richard (Durham, North Carolina, 1965), 83–109Google Scholar; see also Greenbaum, Louis S., “Scientists and Politicians: Hospital Reform in Paris on the Eve of the French Revolution,” in The Consortium on Revolutionary Europe, 1750–1850. Proceedings 1973 (Gainesville, Florida, 1975), 168–191.Google Scholar

44 Parker, Bureau of Commerce, 26; Darnton, Business of Enlightenment, 432.

45 Parker, Bureau of Commerce, 101–102. A flexible combination of a regulation and liberty was characteristic of royal policy long before 1750, according to Deyon, Pierre and Guignet, Philippe, “The Royal Manufactures and Economic and Technological Progress in France before the Industrial Revolution,” Journal of European Economic History, 9 (Winter 1980), 611–632.Google Scholar I am grateful to Professor Edward Gargan of the University of Wisconsin for this reference.

46 Ibid., 102 and 115; see McCloy, Shelby T., French Inventions of the Eighteenth Century (Lexington, Kentucky, 1952), 95–98Google Scholar; on the role of academicians as “controllers of technology,” see Hahn, Roger, The Anatomy of a Scientific Institution: the Paris Academy of Sciences, 1666–1803 (Berkeley, California, 1971), 68.Google Scholar

47 Parker, Bureau of Commerce, 50, 59, 91 and 98.

48 Ibid., 30–37, 56–57, and 63 and 66.

49 Ibid., 130; Stein, French Slave Trade, 72.

50 Ibid., 163–168.

51 See the excellent review essay based on Bourde, André, Agronomie et agronomes en France au XVIIIe siècle, 3 Vols. (Paris, 1967)Google Scholar, by Rappaport, Rhoda, “Government Patronage of Science in Eighteenth-Century France,” History of Science, 8 (1969), 119–136.CrossRefGoogle Scholar An enormous amount of thought and time was expended in attempting to promote new agricultural techniques. Current problems of international development should inspire an understanding of the difficulties involved.

52 Bosher, John F., French Finances, 1770–1795: from Business to Bureaucracy (Cambridge, 1970)Google Scholar; Gelfand, Toby, Professionalizing Modern Medicine: Paris Surgeons and Medical Science and Institutions in the 18th Century (Westport, Connecticut, 1980)Google Scholar; Foucault, Michel, Surveiller et punir; naissance de la prison (Paris, 1975), especially 227Google Scholar; Mousnier, Roland, Les institutions de la France sous la monarchie absolue, 1598–1798, Vol. 2, Les organes de l'Etat et la Société (Paris, 1980)Google Scholar — this remark is based on the review by Moote, A.Lloyd in the American Historical Review, 86, No. 1, (February 1981), 141–142CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Daniel Roche suggests that the cultural product of the royal academies at the end of the Old Regime is “neither bourgeois, nor aristocratic; it is administrative” (Académies, I, 382–383).

53 See Michel Morineau, “Trois contributions au colloque de Göttingen,” in Hinrichs, et al., Vom Ancien Regima, 415; in the case at Angers, the roles of the entrepreneur and the bureaucrats were mutually supportive. See Chassagne, Serge, La manufacture de toiles imprimées de Tournemine-lès-Angers (1752–1820), publications of the Institut Armoricain de Recherches Historiqes de Rennes, No. 10 (Paris, 1971), 127Google Scholar, 180 and 353–356. The same author is preparing a study of the French cotton industry.

54 Among recent local studies of French business practices and the bourgeoisie, see especially those by Livet, Georges and Agulhon, Maurice in the festschrift, Conjoncture economique, structures sociales: hommage à Ernest Labrousse, (Paris, 1974), 189–405 and 465–475.Google Scholar See also Landes, David, “Religion and Enterprise: the Case of the French Textile Industry,” in Carter, Edward C. II, Forster, Robert, and Moody, Joseph N., eds., Enterprise and Entrepreneurs in Nineteenth and Twentieth-Century France, (Baltimore, 1976), 41–86.Google Scholar

55 See Tudesq, A.-J., “Les structures sociales du Regime censitaire,” in Conjoncture économique, structures sociales, 484Google Scholar. Clive Church speaks of an effective “amalgam” of old and new talent in his article, “The Social Basis of the French Central Bureaucracy under the Directory, 1795–1799,” Past and Present, 36 (April 1967), 59–72.