Introduction

Emerging from the civil war that ended in 2002, private sector development was an explicit strategy to reduce fragility and accelerate human development in Sierra Leone. The government, for example, touted “mining for peace”; the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) argued that reforms enacted to attract foreign investors helped make “progress towards achieving peace and stability”; and the African Development Bank claimed to “spread the peace dividend” by “supporting private sector development and business enabling environment.”

Some successes may be claimed. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced at the end of 2016 that “The government's economic reform program supported by the Extended Credit Facility has achieved its key objectives despite the exogenous shocks of the Ebola epidemic and the collapse of iron ore prices”; it implied that the country was on the path to “stronger and more inclusive growth.”Footnote 1 Much was made of the pre-Ebola boom in the extractives sector in which the country marked 22–25 percent GDP growth, making Sierra Leone the fastest growing economy in the world.

Yet Sierra Leone remained in a profoundly fragile state. After the end of the armed conflict enabled an initial improvement in most indicators, the country again experienced rises in prices of basic consumer goods, deterioration in student performance in public exams, and below-average indicators of health, housing, and access to electricity compared to the rest of the continent. The Auditor General more or less continuously questioned the public accounts; the Ibrahim Index of African Governance “accountability” measure of 33/100 showed “warning signs” of deterioration, including a 23/100 score for “diversion of public funds.”

The Ebola epidemic in 2014 put into stark relief the lack of progress in state legitimacy and institutional capacity from the period leading up to the war. The health system failed; decentralized services, internal communications, and border controls evidenced critical weaknesses; and the population demonstrated their distrust in officials with sometimes violent opposition to government responses.Footnote 2 Only considerable foreign financial and technical aid prevented state collapse.

Private-sector led economic growth from 2002 to 2014 did little to break Sierra Leone's cycle of fragility. Indeed,

political, economic and social conditions prevalent in the country show increasing similarities with the past, including widespread under-employment, a sluggish economy, high dependence on the extractives for foreign exchange, rapid fall of the local currency's value against major currencies, and increasing public pressure for accountability.Footnote 3

Additionally, business investment and operations became implicated in other dynamics of the country's persistent fragility, through the perversion of international private sector promotion efforts, the state's implication in citizen insecurity, growing frustration of civil society, and the reinforcement of regional and ethnic tensions. Contrary to the rhetoric of peace dividends and stability, the private sector remained one of the vectors for persistent poverty, increasing inequality, and growing instability.

Despite such realities, international policy and practice increasingly premise exits from fragility on robust private sector development. This was exemplified by the creation by the International Development Association (IDA)—the World Bank's fund for the world's 75 poorest countries—of a U.S. $2.5 billion “Private Sector Window,” implemented in conjunction with the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), “to catalyze private sector investment … with a focus on fragile and conflict-affected states” such as Sierra Leone. It is premised on “the need to help mitigate the uncertainties and risks, real or perceived, to high impact private sector investment” that enables “growth, resilience and opportunity.”Footnote 4

Such policies are premised on a benign view of the private sector potential in fragile and conflict affected states (FCAS) prevalent in the literature. Collier and others have found that the risk of reversion to conflict rises inversely to income; similarly, a reversion to violence becomes more likely the slower the economic recovery.Footnote 5 Private sector development initiatives, therefore, intend to change individual firm behavior in ways that accelerate economic growth, increasing employment and reducing poverty.Footnote 6 Under this line of reasoning, the mere presence and operation of ethical businesses is peace and development positive—identified as a preeminent thrust of the business and peace literature.Footnote 7

Without any apparent irony, the World Bank chose Freetown, in May 2017, as one stage to promote its new Private Sector Window. Yet cases like Sierra Leone, in which private sector development is strongly implicated in endemic fragility, stand as a warning to the limitations of such theory as translated into practice. This is consistent with qualitative analysis from any number of fragile states that show that business operations can contribute to prolongation or exacerbation of conflict,Footnote 8 notwithstanding explicit ambitions to bring a “development dividend” to local populations.Footnote 9 Business resources can intensify competition between groups,Footnote 10 meaning that private sector promotion may as easily undermine peaceful development as support it.Footnote 11 The Sierra Leone case, thus, calls into question the ideas, institutions, and practices underlying the role of private sector development (PSD) in global development and transitions from fragility to peaceful and inclusive development.

As international initiatives to address fragility through PSD accelerate, this gap between policy intention and impact remains of critical importance for both Sierra Leone and other fragile and conflict affected states (FCAS). In the period since 2000, the average growth per capita for FCAS of 1.19 percent per annum remains below that of low- and middle-income countries (LICs) as a whole; their level of volatility is more than three times as high as that of the world average for LICs.Footnote 12 About two-thirds of FCAS did not achieve the Millennium Development Goal of cutting poverty by half.Footnote 13 FCAS economic and social vulnerability therefore remain pronounced.

If the emerging forms of state-business relations represented by ever greater private sector promotion are to play a meaningful role in transitions from fragility to peaceful development in Sierra Leone and other FCAS, it is, therefore, imperative to better understand shortfalls of policy interventions and programmatic implementation related to PSD in such contexts. From a theoretical standpoint, it will be useful to better describe and model the ways in which PSD becomes entangled with socio-political conflict and other dynamics of fragility, so that the trajectories of PSD in Sierra Leone and other FCAS can be better assessed, compared, and understood. This is the intent of this study.

Methodology

The study draws on four data sources to inform its analysis. It began with a comprehensive literature review to plot the trajectory of private sector development from Sierra Leone's founding through the civil war. Desk research illuminated developments in the contemporary period, with a focus on the end of the civil war in 2002 through the Ebola crisis of 2014.

This research was deepened with semi-structured interviews. These included local government officials, community advocates, and private sector actors with direct experience of the impacts of private sector development on conflict and fragility in their communities, as well as country experts, policymakers, and researchers at the country level. Interviews were anonymous following standard practice on conflict sensitive research.

Perspectives from earlier interviews were summarized and related forward to subsequent interviewees for their reflection. This process allowed different perspectives to be brought into contact through an open and emergent process,Footnote 14 largely mimicking the criteria for a focus group.Footnote 15 Insights from such a process cannot be taken at face value. But they should have a high level of content validity—that is, capture the problem framing and perceived levers for action—from the perspective of an expert and experienced cohort.Footnote 16

As the exercise involved both theory generation and provisional testing of theory, a constant comparative method of analysis was used,Footnote 17 based on interview notes. Additionally, a working paper captured preliminary insights from the background research and interview series. Preliminary findings were analyzed and further insights were developed through a consultation session in Freetown that brought together expert academics, economic actors, civil society representatives, and government officials with direct and substantial experience in Sierra Leone. The consultation was conducted under the Chatham House rule.

The study links insights so derived with peacebuilding and statebuilding frameworks to present a model with empirical and theoretical referents for the negative interactions of private sector investment with key factors of fragility. In doing so, it builds toward a more robust explanatory typology.Footnote 18 Here, applied to the policy arena, such typologies have proven important to management research, as they allow research to “represent organizational forms that might exist rather than existing organizations” and to explore combinations of multiple organizational dimensions to arrive at ideal types.Footnote 19 Given the lack of extent theory and models in this domain, this allows the meeting of theory and practice in the development of a parsimonious framework to help describe complex systems and better explain outcomes.Footnote 20

For the practice and policy communities, the strength of such modelling may be, as with soft systems approaches, “its ability to bring to the surface different perceptions of the problem and structure these in a way that all involved find fruitful.”Footnote 21 For the researcher, it presents a novel perspective on the mechanisms of action of the private sector on fragility so that further theoretical propositions can be developed and tested.

The political economy of fragility

By war's end, the horrific and predatory nature of Sierra Leone's private sector had become undeniable. The war in Sierra Leone was described as “a struggle between two rival groups supported by businessmen intent on gaining control of mineral wealth.”Footnote 22 On the one side, De Beers and Lazare Kaplan International bought cheap diamonds from Charles Taylor in Liberia; on the other, security interests and economic ones were closely linked under agreements with President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah.Footnote 23 This was “a violent conflict among multinational corporations in which one company would win handsomely, but the country itself would lose.”Footnote 24

The peace process that ended the armed conflict treated these dynamics as aberrations of war. Only two articles in the Lomé peace agreement signed in 1999 looked beyond the cessation of hostilities to a new socio-political order: Article VII addressed strategic minerals, gold, and diamonds; Article XXVIII, in two paragraphs, spoke to the reconstruction and rehabilitation of the economy. The framework was one of a “return to normalcy” by “rebuilding” the country.

Yet the outbreak of the civil war had simply served to accelerate dynamics already in motion. “The state” in fact had been a veneer hiding the absence of legitimate or effective government,Footnote 25 unable to stop the spread of conflict to the whole of the territory.Footnote 26 Citizens, as well as state and private assets, were left utterly unprotected.Footnote 27

Indeed, analyses of the events of the civil warFootnote 28 and the peace processFootnote 29 underline the degree to which the war represented continuity rather than discontinuity: first, from the roots of fragility into the nature of the war, and second, in the developments during and after the war that laid the groundwork for the dynamics of fragility in contemporary Sierra Leone. Failure to take deliberate measures to “forge a new relationship between the new Sierra Leone and its citizens” from independence to the present “pre-empted the development of a legitimate state with a social contract that bound rulers to the citizenry.”Footnote 30

Continuity was, therefore, the defining feature in the private sector as well. As explored below, from Sierra's independence to the contemporary period, the private sector remained centrally implicated in poverty, increasing inequality, and growing instability.

The economy for the few

Voluminous studies,Footnote 31 including the comprehensive report of the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC),Footnote 32 document how continuity in the extractive economy from the colonial into the post-colonial period maintained a private sector that would increase rather than decrease fragility. High government officials entered into “public-private partnerships” to plunder state assets. As just one example, President Stevens enabled smuggling by making a business associate a shareholder in the national diamond company, leading to a drop in diamond exports reported in government accounts from above 500,000 carats in 1980 to below 50,000 carats in 1988.Footnote 33 As a result of such dynamics, honest indigenous businesses were crowded out, and the only foreign operators were those with high risk appetites, predominantly in the minerals sector.

Against this background, the post-war period similarly experienced obvious and growing income inequalities generated by minerals-led growth. The mineral sector (iron ore, rutile, bauxite, and non-ASM diamonds) was highly capital intensive and returned rents to a disproportionate few, including state officials managing the sector. Much was made of the boom in the extractives sector, which pushed year-on-year GDP growth as high as 25 percent and gave the country the fastest growing economy in the world. In fact, this could be attributed largely to the investment and operations of two iron ore mines.

These mines collapsed in the Ebola epidemic, along with ADDAX, the large sugar plantation. It was established that these companies had wasted productive resources on benefits ranging from private plane travel and free fuel to excessive salaries for politically-connected members of the country's elite, leaving the enterprises no operational buffer when international prices fell.Footnote 34 Many local companies, as well as local subsidiaries of foreign companies, that were tied to these industries also failed. During the same period, international businesses engaged in wholesale corruption. This often took the form of contracts at inflated prices that allowed those in power to capture illicit rents.Footnote 35

Additionally, the land- and resource-hungry enterprises that tend to be promoted by those most focused on personal enrichment, for example, in mining or commercial agriculture, brought them into direct conflict with farming and pastoral communities whose livelihoods were disrupted. Conflict over practices related to large-scale investments in Sierra Leone—from land allocation to lack of prioritization of local employment to deployment of military and paramilitary forces to suppress protest—increasingly evidenced grievances and fault lines that echo the run-up to the civil war.

Policy incoherence and manipulation

In the pre-war period, and, in particular, in the 1980s, the World Bank and IMF insisted on the typical packages of structural reforms. But since the government had no real intent to see agreed upon reforms through, indigenous businesses saw few benefits, and they failed to grow, add jobs, or otherwise demonstrate benefit to the population at large. Monetary policies that restricted credit and foreign exchange, along with increased taxes, put honest private sector actors under continuous stress, while access to goods and services that the government had promised to citizens never materialized. Such incoherent policy implementation, driven by deeply-rooted patronage politics and corruption,Footnote 36 underlay the inequality and inter-group resentment that rendered Sierra Leone more prone to external shocks as well as to internal friction.

In the post-war period, incoherent and sometimes even contradictory policies similarly limited the expansion and productivity of those formal businesses that had been established.Footnote 37 Foreign investors and those who promote them became a key constituency of the government, engendering a dynamic similar to that of the pre-war era. The government accommodated (or attempted to hoodwink) the IMF and World Bank, and did what it needed to in order to attract FDI. It rarely balanced and, more rarely still, prioritized the needs and interests of the informal sector and the real domestic economy. As one example, FEWS NET (the Famine Early Warning Systems Network) in 2015 rated Sierra Leone as in crisis (Phase 3), with the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations reporting that 45 percent of the population did not have sufficient access to food during some period of the year. Yet the government's attention remained focused on international initiatives, such as the New Alliance for Food Security, that are widely criticized by experts (including the UN Special Representative on the Right to Food) for their prioritization of export agriculture into global value chains over local food security.

Such policy initiatives—despite any intended developmental impact—are, therefore, best understood as important catalysts for FDI that became a renewed source of plunder by government officials at elite and lower levels alike. Additionally, the government hid behind international mandates to pursue its partisan political interests. When the IMF, as part of its structural reform package, required the government to reduce its workforce, for example, it targeted perceived opposition members and those from opposition-controlled areas of the country; privatization carried out under IMF and World Bank supervision similarly benefited government supporters.Footnote 38 These actions bred “national divide and animosity, particularly on the part of those regions of Sierra Leone that may feel left out of national development.”Footnote 39

The state's implication in citizen insecurity

As the economy declined in the pre-war period, the executive became increasingly intolerant of dissent and dictatorial.Footnote 40 It controlled all other organs of government, including a police force and a judiciary that were seen to be complicit in politically motivated prosecutions.Footnote 41 These developments contributed to the state's inefficiency and ineffectiveness in delivering public goods and services.Footnote 42 They also led to what has been characterized as a state of institutionalized violence and corruption.Footnote 43

These failures in the rule of law found disturbing equivalents in the post-war period. Media pointed to the arrest and detention of political opponents; civil society noted that the recommendations of Commissions of enquiry set up to investigate government excesses or malpractices were largely ignored. The Human Rights Commission and others documented the use of excessive force on protesting civilians, harassment of opposition politicians, and denial of rights and abuse of discretionary power by the justice system.Footnote 44

Such dynamics played out more specifically in the economic realm, with the legal system and security structures manipulated to support the economic interests of ruling elites. In one case, the high court ruled against a host community, finding that a particular mining company was exempt from the payment of all taxes according to the terms of the mining agreement between the state and the company—although this outcome violated legitimate local expectations, espoused national policy, and international norms and standards. Around Bo Town, in the southern region, government representatives from the opposition party held little sway in national decision-making. There, NGOs report that complaints of abuses against foreign companies engaged in road construction went unheeded, and that the army had been deployed on behalf of government-aligned companies to secure “voluntary” agreements from local communities for resettlement and related compensation. Informants described a potential “powder keg”Footnote 45 where militant structures were being reactivated in response to perceived injustices.

Reinforcement of regional and ethnic tensions

At independence, the British Crown Colony and the Protectorate merged uneasily and incompletely to create Sierra Leone. Colonial mindsets and structures continued under new masters to constitute the formal state.Footnote 46 But these relied on informal state structures based on traditional governance models to ensure local support for actors on the national stage.Footnote 47 This left the local seats of power, the chieftaincies, largely intact.Footnote 48

Even into the contemporary period, the actual allocation of resources controlled by the formal state—including the terms and conditions of government contracts and concession agreements—resulted from an interplay of powerful informal networks based largely on political connections and ethnicity reliant on the informal states. There was the semblance of a formal budgetary process open to the world; yet every year there were wide variations between what was budgeted and what was actually allocated. This reflected the government's role of securing resources through formal means (aid, taxes, and foreign investment) to be distributed by informal means (the decisions of networks controlled by traditional authorities), reinforcing regional and ethnic tensions.

Perversely, the re-introduction of multi-party democracy within the formal state reinforced this system and exacerbated tensions. Under one-party rule, corruption in public contracting spread rents across the country. As the political parties became increasingly regionally—and, thus, ethnically—identified, benefits once shared across traditional authorities were increasingly limited to those aligned with the ruling party. When Libya provided tractors to support food security policy reform, for example, the equipment was sent to strongholds of the ruling party in the northern part of Sierra Leone.Footnote 49 Leaders from the South felt excluded, with some expressing that, when they came to power, it would be “their turn to eat.” The national government and its private sector allies, thus, increasingly became not only a source of tension between the formal and informal states, but between the informal states themselves.

Mounting social frustration

Leading up to the civil war, the vast majority of the population had not experienced the anticipated benefits from the struggle for independence. There was a growing sense that endemic and, indeed, growing inequality was driven by the rent-seeking of both elites and bureaucrats at all levels,Footnote 50 disinterested in any broader exercise in social or economic development. Violence characterized almost every general election.

The formal state was largely absent from the daily lives and informal economy of those living in the former Protectorate; and when it did intervene, the reaction was hostile. The sentiments behind the numerous strikes, riots, and even revolts of the Protectorate period became support for, or at least acquiescence in, the five coup d’états and attempted coups in the post-independence period between 1966 and 1992. The civil war broke out in the isolated border regions with Liberia, where formal state presence was particularly weak and unwelcome.

The post-conflict period evidenced hopeful developments, including freedom of the press and greater knowledge of citizens of their rights. Reports by the Auditor General, the Human Rights Commission, and civil society groups alleging widespread corruption, for example, suggested a more peaceful path for civic frustrations to be expressed. Citizens appeared more willing and more able to demand accountability from the government.

Yet the impact of civil society activism on conflict and fragility was not unambiguous; paradoxically, a free press and greater freedom of association exacerbated tensions, given a government that did not believe it must be responsive. Citizens heard that foreign firms were exploiting natural resources without adequate compensation; it was widely reported, for example, that land in Sierra Leone was valued at only a third of that in Brazil. The lack of medicines in the clinics and teachers in the classrooms despite the enormous financial flows from abroad did not go unnoticed, reinforcing well-grounded historical narratives about the fundamentally corrupt nature of the State. As faster information flows underlined the absence of transparent and credible corrective measures by government to address such widely perceived problems, citizens were left feeling cheated.

As a result of these and other factors, socio-political conflict in Sierra Leone continued to boil over. Seven major strikes and riots in and around mining concessions—some resulting in loss of life—took place in the period 2009 to 2014. The ability of the younger generation to mobilize was particularly evident, as demonstrated by campus protests that could not be suppressed by government as had been in the past, as social media allowed the protests to spread from campus to campus nearly instantaneously. Attempts to suppress student activism through demonstrations of state force became rampant. Violence, which brought Freetown to a standstill in February 2018, was again a defining feature of elections.

The reconstruction of the past

Particularly since 2007, those in power have promised that PSD would transform the lives of citizens. At the state opening of Parliament on 5 October 2007, the former president, who hailed from the private sector, announced sweeping reforms:

Introducing financial sector reform to enhance access to capital … Strengthening the Judiciary to enable quick access to redress … Initiating power sector reform and energy policy management … Conducting a close examination with a view to improving transport and communications in and out of Sierra Leone … Increasing and enhancing skilled labour and improving labour productivity …

This focus was consistent with the push by a range of bilateral and multilateral donor agencies and institutions to reform the business environment to develop the private sector,Footnote 51 premised, as stated by the World Bank, “on the recognition that the private sector is central to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).”Footnote 52 Implementing this international playbook for pro-private sector reform, the president intimated, would allow business—and, thus, the country and its citizens—to prosper.

This hopeful rhetoric is not so dissimilar from the intent for private sector expressed at Sierra Leone's independence. That period saw the continuation of commodity exporters and trading houses from the colonial period. FDI flowed into the mining sector. The state supported light manufacturing under an import substitution strategy, while some indigenous manufacturers and retailers emerged.

However, neither the Lomé peace agreement, nor post-war government policy, nor international development aid recognized, or attempted to resolve, the structural economic contradictions and private sector pathologies that had doomed these hopeful starts and contributed to the outbreak of violent conflict. Indeed, there often seemed to be an obstinate insistence to repeat the past. The IMF and World Bank open-market and austerity measures that had greatly contributed to Sierra Leone's severe lack of distributional justice and extreme poverty in the pre-war period,Footnote 53 for example, were largely recycled in the post-conflict period. These have been found to contribute, inter alia, to the elimination of access to health care for the most vulnerable through the implementation of user fees subsequent to IMF conditionalities imposed on Sierra Leone.Footnote 54

This apparent inability to confront the past allowed private sector drivers of fragility to be re-cemented into the post-war economic order. Business did not change significantly. Middle class business operators continued to function through informal channels, creating high-cost products sold only through collusion with public officials. Legitimate bidders lost out because of patronage, exacerbating feelings of exclusion. Large enterprises in the natural resources sector, meanwhile, made illicit payments in increasingly innovative forms, used partly to cement the positions of recipients who were the custodians of the state's resources. Echoes of past entanglements of armed actors with economic interests were heard in the allegations that government security forces were being used to suppress citizen protests against mining and plantation company excesses.

This contributed to a context in which the political, economic, and social conditions prevalent in the contemporary period showed increasing similarities with the past. The effects on the broad majority of the population were apparent in the dismal and often declining socio-economic indicators of infant and child mortality, hunger index, rankings in access to education, persistent failure to reach minimum thresholds for qualification to the U.S. Millennium Challenge Account (MCC), and poverty levels.Footnote 55 Widespread under-employment, a sluggish economy, high dependence on the extractives for foreign exchange, rapid fall of the local currency's value against major currencies, and increasing public opposition to government policy and practice underlined the country's endemic fragility.

From a linear to a dynamic model of private sector development and fragility

The above findings contradict the narrative—shared by the Sierra Leone government, bilateral donors who are rapidly disengaging, and international institutions promoting private sector investment as the primary solution to the country's underdevelopment—that Sierra Leone has emerged from fragility and, although set back by the shocks of the global financial crisis and Ebola crisis, is on a path towards stable development. It further suggests flaws in the thinking—more formally, the theories of changeFootnote 56—driving much of the policy and practice relating to economic growth and private sector development, particularly as it is advocated for by role players on the outside looking in to conflict-prone environments like Sierra Leone. That model can be captured briefly as follows:

The model posits that policy and aid interventions shape economic growth opportunities and private sector development in ways that ameliorate key factors of conflict and fragility in a linear fashion.Footnote 57 This is captured in the shorthand of the World Bank, as one leading example, as private sector contributions to “security, justice and jobs.”Footnote 58 At the economic policy level, austerity measures are posited to create conditions of macro-economic stability in which more companies invest, in turn creating tax revenues that can be spent on public needs to build state legitimacy. At the level of the business and investment climate, infrastructure investments are said to break down barriers to private sector opportunity; at the enterprise level, project finance for mining projects, or export-oriented plantations supposedly create jobs that increase resilience. Such efforts to promote the private sector are increasingly key development strategies of FCAS in pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals.Footnote 59

This linear model of the impact of PSD on fragility also underpins prevailing models underlying FCAS policy, such as the OECD “dimensions of fragility.”Footnote 60 These tend to measure risks across a variety of dimensions—in the case of the OECD model, economic, environmental, political, security, and societal—and then assume that corresponding packages of interventions that address these presenting conditions reduce fragility itself. They take for granted, as asserted the Freedom of Investment process—an intergovernmental forum on investment policy hosted since 2006 by the OECD Investment Committee—that “international investment spurs prosperity and economic development,”Footnote 61 and thereby contributes to peace.

Yet this model fails to explain the often poor and even perverse results from international programming to reduce fragility—as illustrated in the analysis above for Sierra Leone, where austerity measures became an excuse to remove political opponents from public service, infrastructure projects were used both to reward those who vote a certain way and to line the pockets of corrupt officials, and the increasing dominance of export-oriented agriculture reduced food security and local resilience.

These realities do not seem to deter international actors. They continue to posit private sector promotion as a catalyst of “growth, resilience and opportunity”Footnote 62 in their FCAS programming, policy advice, and funding, rendering the private sector “the new donor darling”Footnote 63 in attempts to address the perceived root causes of conflict and fragility.

This leaves prevailing approaches to PSD largely detached from any analysis of Sierra Leone's political economy, past or present. Policy and practice bypass the question of how today's efforts to promote economic growth and private sector profitability mimic those of the darker, yet not so distant, past; this despite the role the private sector played in enabling and sustaining the country's civil war, as unambiguously set out in the Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.Footnote 64 They fail to address how the private sector impacts, and in turn is impacted by, the many other factors of fragility that persist in contemporary Sierra Leone.

It also puts PSD in Sierra Leone and other FCAS strangely at odds with the evidence questioning linkages of private sector promotion efforts to peacebuilding and statebuilding.Footnote 65 Policy appears to ignore the increasingly compelling global evidence that the mere presence of an enabling environment for a profitable private sector cannot be assumed to be peace positive,Footnote 66 and that, indeed, in many cases the presence of operations of business at scale will cause and exacerbate pre-existing tensions in conflict-prone environments.Footnote 67

Modelling policy and investment in fragile contexts

The findings laid out above suggests a more robust—yet, in its own way, no more complex—model of interventions to address conflict and fragility through economic growth and private sector promotions strategies in states like Sierra Leone. This model describes not only what the presenting risks may be, but why sufficient coalitions for positive change have not been able to coalesce or prevail to address these social, economic, and political conditions, despite the ostensibly positive and well-intentioned economic growth and private sector promotion strategies pursued:

The model draws inspiration from advancements in peacebuilding and statebuilding theory. These increasingly question the utility of a package of interventions “aimed at resolving a conflict by addressing its root causes” in favor of systems perspectivesFootnote 68 that also “ask what factors (actors, issues, motives, resources, dynamics, attitudes, behaviors) maintain or reinforce the conflict system, who would resist movement toward peace, and why.”Footnote 69

The model also intersects with studies showing how “large scale investments in post-conflict and other fragile environments too often become an additional source of conflict rather than delivering on the promise of inclusive growth” through the tendency of fragile political economies to subvert benign interventions intended to support statebuilding or build resilience.Footnote 70 It thereby underlines that the very dynamics of the political order that make a context fragile in the first place—in particular, state predation for personal greed and to reward support by the informal states, accompanied by patronage, exclusion, and capacity underutilization—also undermine programs meant to address it.Footnote 71

To take one hypothetical example, all the same rooted in the above analysis, policy support and project funds may enable the establishment of a palm oil plantation meant to create jobs and tax revenues for public services. But the intermediating dynamics of the key factors of conflict and fragility mean that the negotiation table will include perspectives of the formal but not the informal states; key concessions and contracts will enrich those in power rather than the nation as a whole; and state security services may be deployed to displace people from their traditional lands or stifle their protests.

The private enterprise set in motion by these dynamics, in turn, increases frustration among a well-informed but still relatively powerless civil society, increasing its sense of grievance, and undermines resilience as the macro-economic context and business environment increasingly favor large players in the formal economy that are focused on export of primary commodities over smallholders in the informal economy who are focused on food for local consumption. The policy intervention and investment support posited to reduce fragility in fact has the opposite impact.

Analogous real world cases are widespread in the literature.Footnote 72 The model is, thus, consistent with, and helps to explain, other analyses that find that growth-oriented strategies in FCAS may “preserve in the end, rather than reform, neopatrimonialism” and its attendant elite control over resources.Footnote 73

Additionally, the model suggests how only those policy and aid interventions, as well as private sector initiatives that are acceptable to elites—acting as they understand their own interest in light of these key factors of conflict and fragility—have any hope of achieving meaningful commitment and effective implementation. This helps explain, in the Sierra Leone context, the seemingly endless flow of ideas and resources to the government for seemingly straight forward reforms—for example, the Transformation Development Fund that both civil society and the IMF supported, but all the same could not be advanced in Parliament—that all the same end up in the policy dustbin or are perverted in their implementation. The model is, therefore, also consistent with, and helps to explain, studies elsewhere that find that “institutions enabling and protecting rents extraction” are “protected and buttressed” by elites, while “institutions of power and revenue sharing” are “side-lined and impaired,” leading to “monopolization, elite predation, and usurpation.”Footnote 74

Towards more robust metrics for research and policy impact

Acknowledging the ways in which private sector development becomes entangled with socio-political conflict and other dynamics of fragility should help researchers and policy makers better model and measure the impact of reforms and initiatives that shape the private sector. Doing so will help move policy understanding beyond either the seemingly obsessive focus on growth rates and FDI flows—which this study shows were drivers of increased rather than decreased conflict and fragility in Sierra Leone, both before and after the civil war—or even the measurement of progress against “dimensions of fragility,” which appear to be largely blind to the entanglement of even positively-intended initiatives in the key driving factors of the political economy of conflict.

A starting point for a more robust set of policy metrics may be found in the recognition that significant resources injected into a fragile state context will, absent sufficient, intentional interventions to manage their impacts, have a strong tendency to exacerbate existing tensions and create new ones—a principle long established in the humanitarian and development fieldsFootnote 75 and in company-community practice.Footnote 76 In the context of economic growth policy, investment climate reform, and PSD, the Sierra Leone and related analyses suggest that three dynamics appear particularly pronounced:

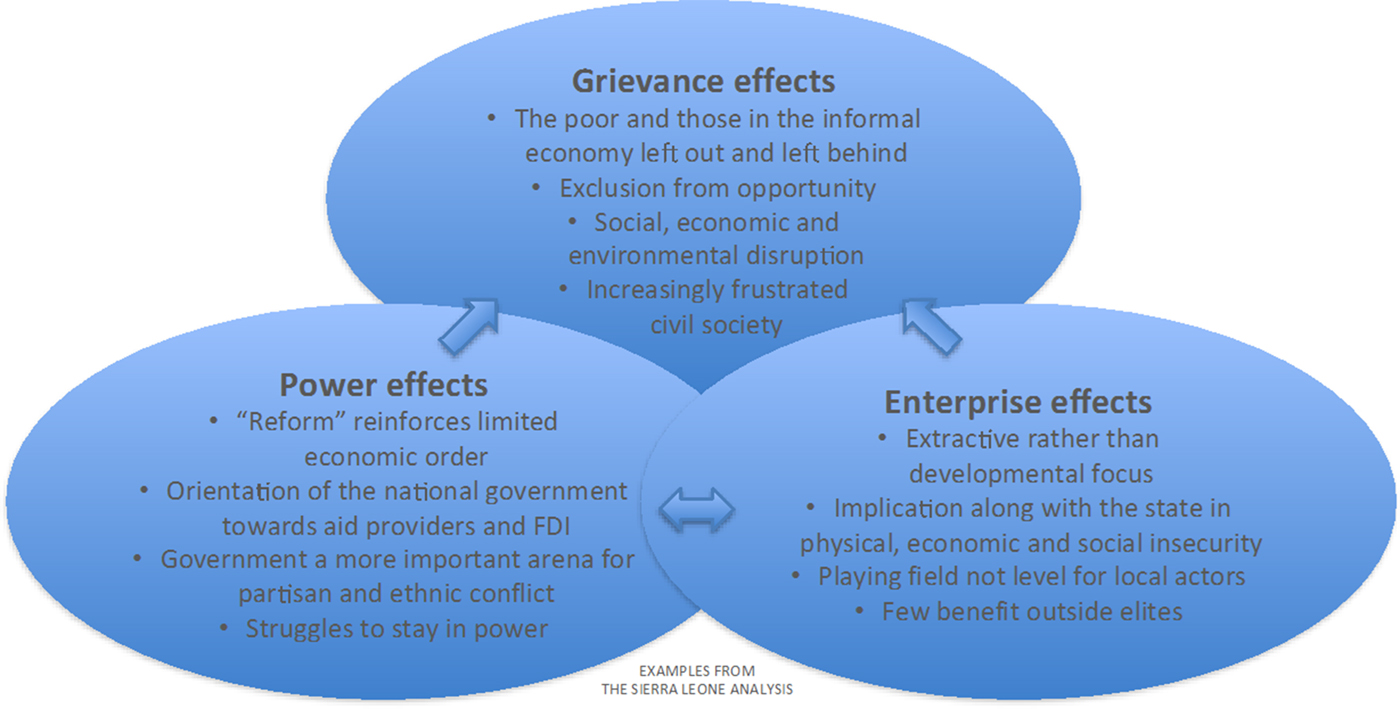

Power effects

Reform efforts and investments will tend to concentrate power and resources with the allies of the government in power, both by making more of the economy subject to the controls of macro-economic policy and national institutions (e.g., through policies that concentrate and depend on large-scale extractive enterprises), and by creating opportunities for those in power to enrich themselves and their allies. Furthermore, in order to secure control over additional resources, government attention is focused away from policies more beneficial for inclusive growth towards those favored by external institutions and investors. The formal government becomes an even greater arena for conflict, as resentments over mal-distribution of national resources grows in the face of allocation of state assets to loyalists and relatives in the form of land, contracts and positions. Incumbents become desperate to stay in power, both so the “plunder” described by the TRC (2004) can continue and impunity for past indiscretions can be assured.

Enterprise effects

The private sector enterprises that emerge from these power dynamics are primed to replicate the extractive practices of the past. Enterprises at any scale are necessarily part and parcel of the closed economic order; they play roles in shaping decisions—from tax policy to government procurement—to their benefit, not that of the people as a whole. They rely on the support of state security and justice institutions to suppress opposition by traditional institutions, communities, or individuals to their presence and operations. There are few incentives to comply with environmental or social standards that reduce enterprise profitability for shareholders and government patrons alike. The prevalence of small players in global markets facing little reputational risk from questionable behavior, together with a capital-intensive mining industry that shares rents more with compromised officials than with the national treasury, yield little to the poorer classes.

Grievance effects

Power and enterprise effects together exacerbate tensions and grievances that are at the heart of conflict and fragility. The population sees economic policy and infrastructure development geared towards local elites allied to large enterprises and their foreign sponsors, while UNDP counts around 80 percent of the population as poor (2016) of whom the vast majority are within the informal sector. The phenomenon of exclusion is pervasive due to the interplay of the ethnically based informal states with multi-party democracy, notwithstanding the token non-ethnic appointments and contracts. The judicial system is considered partisan and biased towards wealthy elites and their private sector interests. An increasingly well-informed civil society grows in frustration as it fails to stop any but perhaps the most egregious cases of abuse across all of the dimensions outlined above.

These observations are captured below, illustrating for Sierra Leone the nexus between private sector promotion and development, on the one hand, and key driving factors of conflict and fragility, on the other:

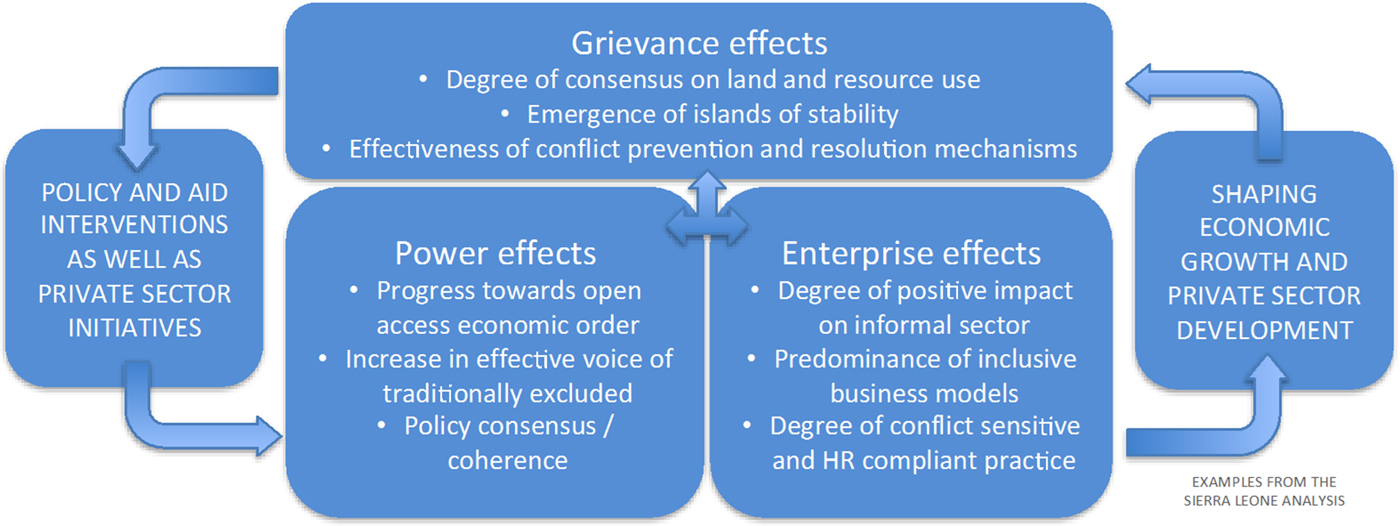

This suggests that a more robust set of metrics—whether for research, for policy and institution actors on the international stage, for constructive national actors, or for an individual enterprise attempting not only to “do no harm” but contribute to peaceful development—may not be so difficult to conceptualize. It requires only recognition that any intervention become part and parcel of the political economy of conflict; and that policy, aid, and PSD interventions will therefore have an impact, positive or negative, on key driving factors of conflict and fragility. Furthermore, interventions will be mediated by the dominant dynamics of the system, shaping the private sector that emerges and its impacts on fragility.

More useful metrics for research and more effective metrics for policy interventions would track aggregate impacts along dominant vectors of the conflict system, any of which could be positive or negative:

Applying such metrics, evaluation of a proposed investment scheme the power effect of which was to further concentrated power, for example, would be understood to reinforce fragility. These same metrics would favor investments that helped to create a more open economic order. In the realm of enterprise effects, policies could be evaluated for their direct enabling impact on the informal sector (as done in Ethiopia to lift tens of millions of smallholder farmers out of povertyFootnote 77), rather than prioritizing national tax revenues that bring little local benefit in fragile contexts. Attentiveness to grievance effects would focus attention on policy coherence and policy consensus much more inclusive of civil society and opposition voices to address problems and forge solutions. In other words, modelling and measuring policy initiatives against such metrics help actors to shape power, enterprise, and grievance dynamics for positive rather than negative impact on fragility.

Application of such metrics to research, understand, and evaluate policy and aid interventions, as well as discrete private sector initiatives, has a number of implications for research and theory development. First, international actors have advocated for some time that private sector actors adopt conflict sensitive business practices.Footnote 78 This analysis supports the notion that such efforts are critical—and, indeed, much more difficult than typically acknowledged, due to the intermediating effects of key dynamics of conflict and fragility on any attempts by companies to act in conflict sensitive ways or for outside actors to influence them.

Second, the analysis underlines that policies and initiatives to promote economic growth, shape the investment and business climate, and promote PSD must themselves be conflict sensitive if they are to not reinforce conflict and fragility rather than promote peaceful development.

Third, all actors must be aware of aggregate impacts on the system. This is true for individual private sector actors—the positive impact of whose good practice or program may be overwhelmed by their own negative impacts on the system elsewhere—and also true for international actors, who must be attentive, for example, to the regional distribution of private sector projects, as well as the aggregate attentiveness or inattentiveness to the interests of domestic actors and the informal sector vis-à-vis those of large and often foreign enterprises.

Implications for Sierra Leone

The analysis finds that conclusions that Sierra Leone is on a path to greater stability or inclusive growthFootnote 79 are overstated, and that the truer story is one of the persistence of historical dynamics that underpinned fragility. Manipulation of the formal structures of government for elite predation and a focus on rent-seeking at all levels of the bureaucracy remain particularly pronounced. Relative calm may prevail because of popular weariness with conflict. But people feel increasingly insecure as they perceive both their economic prospects and their traditional institutions to be under attack.Footnote 80 Conflict risks remain high and may be increasing, with private sector promotion and development found to be specific vectors along which fragility manifests and increases.

In light of these observations, it appears that a model that puts the mediating effects of the key factors of conflict at the heart of analysis should bring us closer to the critical questions for inclusive growth and private sector development strategies that more effectively address conflict risk and fragility: What are the power relationships or institutional arrangements that ameliorate, rather than reinforce, fragility? Given that no society chooses poverty or insecurity, what has inhibited a sufficient coalition for change from forming? In what domains might it be possible for one to emerge? And what kinds of international interventions—particularly in the realm of PSD—might help them do so?

Such questions will necessarily move analysis away from a focus on presenting conditions in which it is assumed that conflict risk and fragility are reduced if an enterprise that nudges the youth unemployment rate lower is created, or if better legislation is introduced in the extractives sector. They will usefully move analysis towards assessment of what we might call the political economy of fragility: socio-political dynamics inhibiting the mobilization of coalitions sufficient to confront and change power relationships and institutional arrangements that exacerbate problems rather than provide solutions. As international and domestic actors design and implement policies and programs for inclusive growth and greater economic opportunity, including private sector promotion, they move from a focus on what is not there—for example, jobs or public services—to understanding what is there—powerful dynamics inhibiting positive change.

The model developed above demonstrates that these dynamics are not necessarily difficult to understand. To the extent it helps to explain the persistence of fragility in Sierra Leone, there are warnings for those attempting to use private sector development to deliver peaceful and inclusive development in fragile and conflict-affected contexts. As a regional divide becomes increasingly evident along ethnic lines in Sierra Leone, these findings take on urgency. They can be summarized as follows, in some cases refining and in others challenging prevailing policies towards PSD, conflict, and fragility in Sierra Leone:

Policy premised on a “return to normalcy” or “return to peace” by “rebuilding” the country rests on unstable conceptual and factual foundations. Neither the Lomé peace agreement nor subsequent political developments established a new social contract. Rather, they provided avenues for the root causes of conflict in Sierra Leone to continue into the present period.Footnote 81 Since the fundamental trajectory of conflict related to private sector development has not been altered,Footnote 82 current levels of conflict may not be indicative of actual conflict risk.

Capital intensive growth yields returns to few within the country. High growth in Sierra Leone has only been achieved through the export of minerals, as well as by shifts towards plantation agriculture and cash crops. Whether through symptoms of the Dutch Disease, increased land conflict, or otherwise, these developments have tended to increase inequality, decrease resilience, and expose more people to greater economic insecurity.

Traditional institutions of the informal states, as well as the human security and social stability they have historically provided, are undermined by rapid, poorly managed growth. They become less able, for example, to deliver conflict resolution or justice. Generous (even if unsustainable) assistance by international aid organizations, further reduces their legitimacy.Footnote 83

“Statebuilding” initiatives may have perverse impacts. There are currently no mechanisms or structures through which Sierra Leone's many, largely informal, power centers can reach durable understandings on the proper distribution of the costs, risks, and benefits of private sector development. Thus, attempts to increase the ability of the formal state at a national level to control and allocate resources mostly increase its prominence as a target for inter-group contestation.Footnote 84

Accelerated economic growth without commensurate management of inter-group dynamics—whether inter-ethnic or rural-urban—will predictably exacerbate fragility and enable conflict. Elites—in both the political class and the bureaucratic class—within a limited economy exercise inordinate control over the formal economy. The distribution of benefits and risks from economic growth remain skewed and highly contested; additional resources, particularly at scale, mean additional fuel on the fire.Footnote 85

Conclusions and future research directions

If Sierra Leone is to move away from fragility, national as well as international actors must face the past and see its shadow on the present. Yet former President Koroma at the closing of Parliament in December 2017 laid claim to a highly successful ten-year stint, notwithstanding data showing declining conditions for the bulk of the population;Footnote 86 successive IMF reports still continue to praise the government. Critical voices are rarely acknowledged by policy actors, despite currency devaluations, high interest rates, rising public debt, and the evident weaknesses of the real economy.

The private sector is typically defined as that part of the economy that is not controlled by government. Under this classical formulation, Sierra Leone has little private sector at scale. Any true private sector is constrained by a limited economic order in which rent-seeking behavior dominates all major sectors of the formal economy, including mining, commercial agriculture, infrastructure development, and industry. Major private sector actors appear to be willing partners in economic policies and business practices that reflect aligned elite and foreign interests, rather than sustainable, inclusive, and peaceful development path for the country as a whole.

These dynamics render Sierra Leone vulnerable to the historical dynamics underpinning state failure and civil war. The informal states compete for power over—rather than seeking to strengthen or build the legitimacy of—national institutions. Public distrust driven by a variety of forms of corruption, government unwillingness or inability to enforce regulations, and a general indifference to public imperatives undermine state capacity to address shocks like the Ebola crisis. Security forces and the justice system are abused for private ends, escalating the state-society crisis and rendering individual security impossible. Recent community protests, student manifestations, and election violence—unfolding in a context in which localized riots and strikes historically preceded national conflict—demonstrate how easily chronic popular dissatisfaction with government can result in conflict and violence.

Building on analysis of historical and contemporary dynamics, the model constructed aspires to make these connections between private sector development and Sierra Leone's sustained fragility more explicit and more testable. The model also asserts, however, that they need not remain true. It suggests paths by which private sector policy and investment might contribute to consequential changes in the country's power structures and institutional arrangements—notwithstanding their apparent resilience in the face of crisis and violent conflicts—by applying the lenses of power effects, enterprise effects, and grievance effects within a dynamic systems understanding to promote a positively—rather than negatively—reinforcing political economy.

Built inductively from practical insight into the role of the private sector in Sierra Leone, the model also guides further inquiry. It posits explanatory variables—in particular, the intermediating variables of power, enterprise, and conflict effects—as entry points for research into the effectiveness of private sector promotion and investment policies in fragile contexts with empirical and theoretical referents. As such, the model serves as a constructed type, selecting and accentuating distinctive aspects of the negative (and potentially positive) interactions of private sector policy, investment, and business operations with key drivers of conflict and fragility, allowing future case studies to be described in comparable terms.Footnote 87

The model also posits causal relationships that guide exploration of outcomes and their association with different variables, building toward a more robust explanatory typology.Footnote 88 It is, thus, a modest step towards an empirically rigorous and theoretically sound description of the policies and practices that might make more real the promises—so far unfulfilled—of private sector development in service of inclusive growth, resilience, and peaceful development in fragile contexts.