1. Introduction

The Yasna constitutes the core ritual of the Zoroastrian religion. Composed in an old Iranian language called Avestan, the Yasna attests to different stages of the language known as Old and Young Avestan and probably also Middle Avestan.Footnote 1 While the Old Avestan texts were presumably composed in the second millennium bce, the composition of the Younger Avesta belongs to a later stage of the language, starting from the late second or early first millennium bce onwards. These texts were in all likelihood transmitted in an oral setting until the Sasanian period (224–651 ce) when they were written down in a consciously invented and extremely precise phonetic script reflecting the exact pronunciation of the words. During the Sasanian and early Islamic periods, Zoroastrian priests translated and commented on the Yasna in Pahlavi, the Middle Iranian language of the province of Pars, used by the Zoroastrians well into Islamic times.Footnote 2 Traditionally, manuscripts that provide the Avestan recitation text of a ritual and the ritual instructions which may be in Pahlavi, New Persian or Gujarati are called sāde “simple”, while manuscripts in which the Avestan text of the Yasna is accompanied by its corresponding Pahlavi translation and commentary are referred to as the Pahlavi Yasna. The codices are also categorized into two groups according to their origin: Indian and Iranian. While the former were produced in India, the latter are manuscripts either produced in Iran or copied in India from a manuscript of Iranian origin.Footnote 3

The oldest Pahlavi Yasna manuscripts at our disposal, J2 and K5, belong to the Indian branch and were written in 1323 ce.Footnote 4 The extant manuscripts of the Iranian Pahlavi Yasna (henceforth YIrP) date from around 1780 ce. Their chief representatives are Pt4 and Mf4, but there are also other manuscripts that belong to this group, in particular the hitherto largely neglected manuscripts T54, G14 and T6.Footnote 5

The YIrPs of the type Pt4 and Mf4 are marked by two features. One is that they include not only the Pahlavi translation but also the ritual directions typical for the liturgical or sāde manuscripts. This feature was also familiar to the scribes of these manuscripts themselves, since they refer to them as abestāg ī yašt abāg zand nērang “the Avestan Yašt with explanation (= Pahlavi version) [and] ritual directions”.Footnote 6 The other special feature of YIrPs of the type Pt4 and Mf4 is a long Introduction in Pahlavi which includes the text of the two colophons under investigation in the present article.Footnote 7 While the first, younger colophon belongs to the ancestor manuscript of these copies, the second colophon recounts the story of how the Avestan recitation text was combined with its Pahlavi translation-cum-interpretation in a single manuscript.

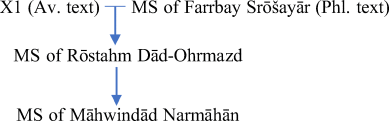

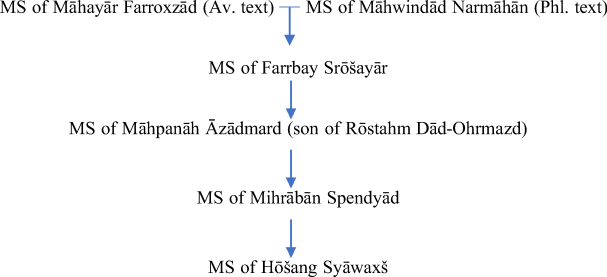

In this article, I first explain the position of the colophons in the context of the Introduction (section 2) and discuss the dates of the manuscripts of the YIrP (section 3). Section 4 presents the text of the colophons as attested in Pt4 in transcription and collated for the first time with the four other manuscripts Mf4, T54, G14 and T6. This is followed in section 5 by a summary of scholarly interpretations of the colophons and an overview of suggestions put forward in the present article. The main arguments of this article are developed in section 6 in which I discuss the text of the second colophon and propose a new reconstruction of the genesis of the Pahlavi Yasna. I suggest that Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd produced the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript for himself and Māhayār Farroxzād. This codex was then copied by Māhwindād Narmāhān. I also suggest that the name of the scribe of the Avestan source of Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd's manuscript is not mentioned while that of his Pahlavi source was Farrbay Srōšayār. Section 7 discusses the name of the province of bīšapuhr “Bīšāpuhr”, from which Māhayār Farroxzād came, and the attribute anōšag “immortal”, which precedes the name of Māhwindād Narmāhān. In section 8, I make a critical study of Kāyūs's texts in the manuscripts T54, G14 and T6 because: 1) according to their colophons, they were either written by a scribe called Kāyūs (T54) or copied from his manuscript (G14, T6); and 2) the first colophon of T54 offers a different filiation from all other collated manuscripts of YIrP. In section 9, I examine the variant readings of geographical locations, personal names, the first-person pronoun preceding Māhwindād Narmāhān, and az ham paččēn paččēn-ē in G14 and T6.

2. Position of the two colophons in the context of the Introduction in the manuscripts of the Iranian Pahlavi Yasna

The long Introduction which precedes the beginning of the text of the Yasna proper extends over several folios (henceforth fol., singular, and fols, plural) in the YIrPs. The first part of the Introduction starts with praises of Ohrmazd, the Amahraspands, the Mazdean religion, the Frawahr of the righteous and of the sacred beings, or Yazds.Footnote 8 These are followed by curses of Ahriman and his creatures such as demons, demonesses and sorcerers. The text continues with a short reference to the story of creation according to which the Amahraspands, Yazds and the Mazdean religion were created by Ohrmazd to annihilate Ahriman, the demons, the power of evil and of violence, and also to bring about the resurrection and future body. According to the text, the religion was revealed to Zardušt and was passed down from him to other priests. The first part of the Introduction ends with advice that everyone should talk and even write extensively about the religion.Footnote 9

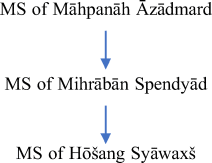

At precisely this point, which is marked by the injunction to disseminate the religious teachings, the two colophons are placed in the manuscripts.Footnote 10 With the exception of T54, the first colophon belongs to a manuscript that was written by Hōšang Syāwaxš.

The text of the first colophon is different in T54 in so far as it includes an insertion at the beginning of the first colophon, stating that Kāyūs Suhrāb copied the manuscript of Hōšang. Kāyūs's text is also present in G14 (fol. 21r lines 6–12) and T6 (fol. 8v lines 3–9) with two major differences: 1) the name of Kāwūs (= Kāyūs in T54)Footnote 11 appears as the third-person singular in G14 and T6; and 2) unlike T54, Kāwūs's text is placed in a third colophon at the very end of part 2 of the Introduction in G14 and T6, thus forming a separate colophon. In other words, the text of the first colophon in G14 and T6 agrees with that of Pt4 and Mf4. In all five YIrP manuscripts discussed here, the first colophon is immediately followed by the second one, which, as noted above, recounts the story of how the first known bilingual Pahlavi Yasna manuscript was created.Footnote 12

The second part of the Introduction which follows these colophons again starts with prayers and advice. The last lines are a reminder that whoever owns the manuscript should only share it with people who are knowledgeable about religion.Footnote 13

3. Dates of the manuscripts of the Iranian Pahlavi Yasna

Neither of the two colophons provides a date, but the manuscript Pt4 is dated around 1780 ce, according to the family tradition of its previous owner, Dastur Pešotanji Behramji Sanjana (Hintze Reference Hintze2012: 253). The manuscript Mf4, by contrast, attests a date in its third colophon which is unique to this manuscript. This colophon forms no part of the Introduction but is inserted at the end of Yasna 61 on pp. 599–600 of Mf4. Stating that Hōšang Syāwaxš completed his manuscript in ay 864 (1495 ce), it provides the completion date of the ancestor manuscript of the Iranian Pahlavi Yasna, but not that of Mf4 itself.Footnote 14 According to the estimation of Geldner (Reference Geldner1896: Prolegomena xxv), Mf4 “appears to be somewhat younger than Pt4, but the difference in age cannot be much” because:

Mf4 omits some more words than does Pt4, e.g. in the Pahlavi to Yasna 68,7.21; 71,8.12. The injury to the Hôshâng Ms.Footnote 15 which already existed in the year 1780 had therefore advanced still further by the time that Mf4 was copied.

T54 likewise bears no date (Hintze Reference Hintze2012: 255) but G14 gives a date in its colophon following part 2 of the Introduction. It states that Kāwūs completed his manuscript in ay 1149 (1780 ce). While the colophon of Kāwūs in G14 is copied in T6, the latter differs from all other manuscripts in that it has two more colophons, one in New Persian and one in Gujarati. According to the Gujarati colophon, T6 was completed by Sorābji Frāmji Meherji Rāna from the copy of Kāvasji (=Kāwūs) in ay 1211 (1842 ce).Footnote 16 It should be noted that the New Persian colophon in T6 (fol. 295v lines 5–7) is peculiar as the completion date, written both in numbers (1211) and in words (one thousand and eleven), shows a discrepancy of 200 years. That the completion date ay 1211 written in numerals in the New Persian colophon is the correct one emerges not only from the fact that it agrees with that of the Gujarati colophon, but also because the date of one thousand and eleven predates the completion date of its stated source, the manuscript of Kāvasji (= Kāwūs).

4. Text of the colophons in Pt4 and the variant readings in Mf4, T54, G14 and T6

All previous studies of the colophons of the Iranian Pahlavi Yasna have been based exclusively on the manuscripts Pt4 and Mf4. West (Reference West1896–1904: 84–5) provides a transcription in Roman letters of the colophon text of Pt4 accompanied by an English translation and a short commentary. Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923) reproduces the Pahlavi text of the Introduction of Mf4 (pp. 90–3) in Pahlavi script and also translates it into English (pp. 114–18). Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 321–32) gives a detailed study of the colophons, accompanied by a German translation, but omits the original Pahlavi text.Footnote 17 The only complete edition of the entire Introduction currently available is Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 73–83), who transcribes the Pahlavi text based on the edition of Dhabhar and translates it into New Persian. Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 31–42) edit the colophon texts using the manuscripts Pt4 and Mf4 and translate them into English.

In what follows, the text of the colophon in Pt4 is compared for the first time not only with that in Mf4 but also with the text in T54, G14 and T6, whose variant readings are recorded in the footnotes:Footnote 18

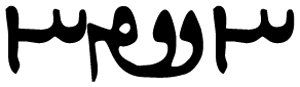

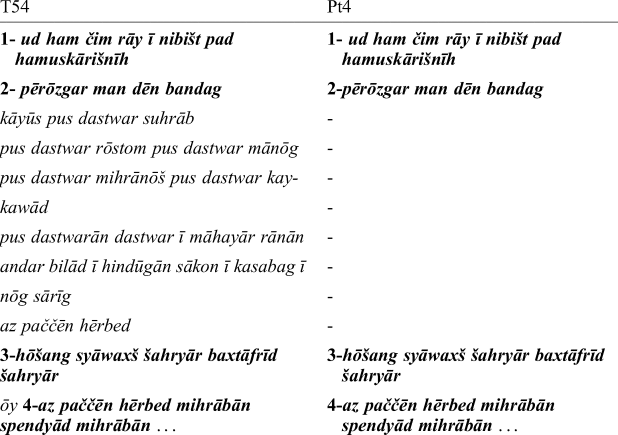

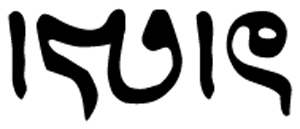

Colophon 1

Pt4 (3r line 21) … ud ham čim rāy ī Footnote 19 nibišt (3v 1) pad hamuskārišnīh

pērōzgar man dēn bandag Footnote 20 hōšang (2) syāwaxš šahryār baxtāfrīd šahryār Footnote 21

az Footnote 22(3) paččēn hērbed mihrābān spendyād mihrābān Footnote 23

(4) ōy az paččēn hērbed Footnote 24 māhpanāh Footnote 25 ī Footnote 26 āzādmard

ī Footnote 27 (5) panāh ī az kāzerōn rōstāg

čiyōn Footnote 28 mard Footnote 29 nēk (6) abarmāndīg Footnote 30

pad dēn ud ruwān abēgumān

u-š kāmag (7) frārōn ō Footnote 31 yazdān wehān

“(3r line 21) … and for this reason, (I) wrote [this copy] (3v 1) with the inspiration of

the victorious [Yazds],Footnote 32 I, the servant of the religion, Hōšang (2) Syāwaxš Šahryār Baxtāfrīd Šahryār,

from (3) the copy of Hērbed Mihrābān Spendyād Mihrābān [and]

(4) that from the copy of Hērbed Māhpanāh son of Āzādmard,

the (5) protector, from the region of Kāzerōn

like a good (6–7) heir (?),

without doubt concerning the religion and the soul,

and with an honest desire for the good Yazds.”

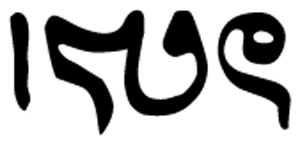

Colophon 2

rōstahm ī Footnote 33 dād-ohrmazd (8) nōgdraxt

ī az farrox būm ī spāhān az rōddašt Footnote 34 (9) rōstāg az Footnote 35 warzanag deh

abestāg az paččēn-ē Footnote 36 (10) ud zand az paččēn-ī Footnote 37

anōšag farrbay srōšayār xwēš (11) rāy nibišt ēstād

jādag Footnote 38 anōšag ruwān māh- (12) ayār ī Footnote 39 farroxzād

ī Footnote 40 az ham bīšāpuhr Footnote 41 awestān Footnote 42 (13) az kāzerōn Footnote 43 rōstāg Footnote 44

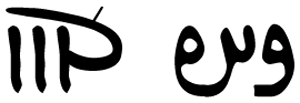

anōšag ī man Footnote 45 māhwindād ī Footnote 46 (14) narmāhān Footnote 47 ī Footnote 48 wahrām mihr

az ham Footnote 49 paččēn paččēn-ē Footnote 50

az (15) xwāyišn ī pērōzgar abunasr Footnote 51 mardšād ī šāpuhr Footnote 52

(16) az farrox būm ī Footnote 53 šīrāz

“Rōstahm, son of Dād-Ohrmazd (8) NōgdraxtFootnote 54

from the blessed land of Spāhān, from the Rōd-Dašt (9–11) region, from the town of Warzanag,Footnote 55

had written [a copy], the Avesta from a copy, and the Zand from the copy of

the immortal Farrbay Srōšayār, for himself [and]

for the immortal souled Māh- (12) ayār son of Farroxzād

from the same Bīšāpuhr province, (13) from the region of Kāzerōn.

I, the immortal Māhwindād son of (14) Narmāhān son of Wahrām Mihr, [wrote]

from the same copy, a copy

at (15) the request of the victorious Abunasr Mardšād son of Šāpuhr

(16) from the blessed land of Šīrāz.”

5. Interpretations of the colophons

EightFootnote 56 personal names occur in the colophon text according to the following sequence:

1) Hōšang Syāwaxš Šahryār Baxtāfrīd Šahryār;

2) Mihrābān Spendyād Mihrābān;

3) Māhpanāh Āzādmard;

4) Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd;

5) Farrbay Srōšayār;

6) Māhayār Farroxzād;

7) Māhwindād Narmāhān Wahrām Mihr; and

8) Abunasr Mardšād.

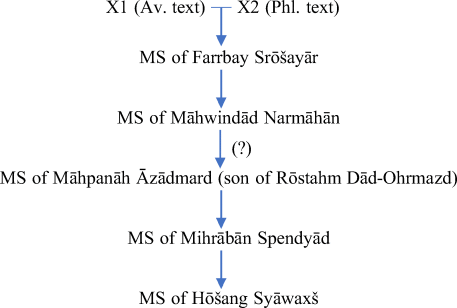

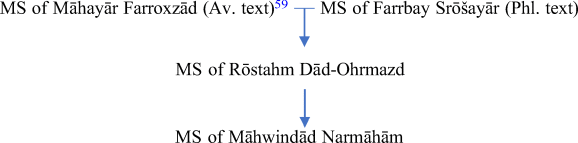

The main scholarly disagreements on the interpretations of the colophons concern 1) the scribe(s) of the colophon text; 2) the name of the creator of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript and the point of transition between the first and the second colophon; and 3) the scribes of the Avestan and Pahlavi sources of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript. These three questions are discussed in detail below. However, before discussing them, it may be useful to survey the filiations proposed by different scholars summarized as follows:

(i) The model of West (Reference West1896–1904: 84–5)Footnote 57

(ii) The model of Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115–16)Footnote 58

In Dhabhar's view, the names of the scribes of the Avestan and Pahlavi manuscripts that were combined in the first Pahlavi Yasna codex are unknown. Furthermore, it is unclear from his translation whether or not the manuscript of Māhpanāh Āzādmard was directly copied from the first copies written by Farrbay Srōšayār and Māhwindād Narmāhān.

(iii) The model of Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 332)

Colophon 1 (written by Hōšang Syāwaxš)

Colophon 2 (written by Hōšang Syāwaxš)

(iv) The model of Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 80–1)

Mazdapour does not draw a diagram. She cautiously translates the text and states in her introduction that “because of the ambiguity that exists in the writing, borders between the sentences cannot be distinguished clearly, and as a result, one can reach a different semantic conclusion with revisions in these transitional points” (Mazdapour Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 72).Footnote 60 Therefore, she places asterisks above her suggested transitional points in sections that contain the personal names, hoping that her suggestion may contribute to future research on this subject. Furthermore, Mazdapour, who considers the whole Introduction to be a work of Hōšang, does not discuss the number of colophons in the text. As a result, I have drawn the diagram according to the asterisks that she placed between the sentences.

Following Mf4, Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 74–5) edits line 2 az as ōy az:

nibišt … man, dēn bandag, hērbad hošang siyāwaxš šahryār baxt-āfrīd šahryār* ōy az pačēn hērbad mihr-ābān spendyād mihr-ābān, …

She also translates the phrase as follows:

“I, the servant of the religion, Hošang son of Siyāwaxš son of Šahryār son of Baxt-āfrīd son of Šahryār wrote <from the manuscript of the one> who from the manuscript of Hērbad Mihr-ābān son of Esfendyār son of Mihr-ābān <and> …” (Mazdapour: Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 80).Footnote 61

It emerges from the translation that Mazdapour assumes that a manuscript by an unknown scribe intervenes between the copy of Mihrābān and that of Hōšang. In the present article, I have followed the straightforward reading of Pt4 in translation.

Māhwindād Narmāhām is also considered by Mazdapour as a figure whose name was written on a manuscript (see section 5.1). Moreover, it is unclear from Mazdapour's translation whether or not the manuscript of Māhpanāh Āzādmard was directly copied from that of Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd.

(v) The model of Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 40)

Colophon 1 (written by Hōšang Syāwaxš)

Colophon 2 (written by Māhwindād Narmāhān)

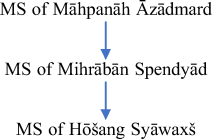

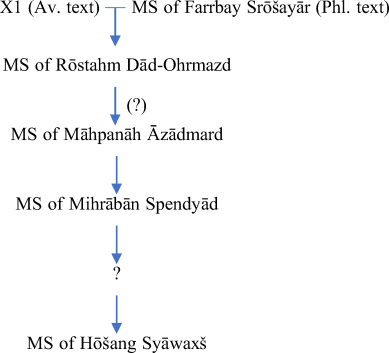

(vi) My proposed model

I propose the following filiation and present the justification of it in sections 5.1, 5.2, 5.3 and 6:

Colophon 1 (written by Hōšang Syāwaxš)

Colophon 2 (written by Māhwindād Narmāhān)

5.1 Scribe(s) of the colophon texts

While there is no question that Hōšang appears as the first person, man dēn bandag hōšang “I, the servant of the religion, Hōšang”, at the beginning of the first colophon, West (Reference West1896–1904: 84) cautiously takes the whole Introduction as a production of Hōšang and “as a specimen of fifteenth-century Pahlavi as written in Iran”. Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: v) and Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 72) make the same suggestion. Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 323–4) ascribes both colophons to Hōšang too, but considers them to have been inserted into the Introduction, which he attributes to the ninth–tenth century at its latest on the basis of the form of its Pahlavi language.Footnote 62 Geldner (Reference Geldner1896: Prolegomena xxv) had already noted that the text bears more than one colophon although he considered the connection between the colophons to be unclear. Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 332) was the first to posit two colophons in his diagram. More recently, Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 37), who also recognize two colophons, have convincingly argued that the second colophon belongs to a different scribe.

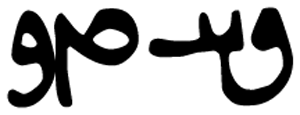

While it is obvious that the first colophon is by Hōšang, the attribution of both colophons to Hōšang by West, Dhabhar, Tavadia and Mazdapour rests on their interpretations of the first-person pronoun man “I” which precedes Māhwindād:

Pt4 (3v13) anōšag ī man (written heterographically as  ) māhwindād ī (14) narmāhān ī wahrām mihr

) māhwindād ī (14) narmāhān ī wahrām mihr

West (Reference West1896–1904: 85) translates man as “(of) me” and suggests that the Pahlavi source of the first Pahlavi manuscript was the production “(of) me, the immortal Māhwindād, son of Narmāhān, son of Wahrām, son of Mihr(-ābān)”.Footnote 63 However, his translation is problematic because it is based on the hypothetical insertion of “of” in round brackets and the erroneous translation of jādag as “production” as discussed in section 6.4.

Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 325) leaves man untranslated. Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 116, fn. 1) takes the Pahlavi sign as a corrupt form or an abbreviation of ruwān.Footnote 64 It is obvious that Dhabhar's suggestion is entirely hypothetical since he adduces no justification for, nor parallels of, such an abbreviation or corrupt form.

Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 81) adds the hypothetical <from-a manuscript-that-name>Footnote 65 and <on itself-held>Footnote 66 before and after anōšag ī man māhwindād ī narmāhān ī wahrām mihr, respectively, as follows:

“*<from a manuscript that held the name of> the immortal <souled>: (of) me, Māhwindād son of Narmāhān son of Bahrām son of Mihrābān <on itself>, from the same manuscript*”Footnote 67

Therefore, in Mazdapour's interpretation, as in West's, while Māhwindād son of Narmāhān appears as the first person, he is not considered to be the scribe of the colophon. Moreover, Mazdapour has kindly informed me that she considers man to be a scribal mistake. Mazdapour's interpretation therefore requires several assumptions. It should be noted that Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 75–7, 81–2) includes more sentences from the Introduction into the (second) colophon and associates the verb nibišt, which occurs twice in her suggested concluding text, with Hōšang:

“anōšag ī man māhwindād ī nar-māhān wahrām mihr az ham pačēn, pačēn-ē az xwāhišn ī pērōzgar abū-nasr mard-šād ī šāhpuhr ī az farrox būm ī šīrāz; … hāt hāt u kardag kardag, pad abestāg, … nibišt … pad daxšag u ayād dāštan ī rōz ī frajām u xwārīh u āsānīh u nēkīh

pad wahišt rāy, čand hu-wizārīhātar dānist, nibišt”

“<from a manuscript that held the name of> the immortal <souled>: (of) me, Māhwindād son of Narmāhān son of Bahrām son of Mihrābān <on itself>, from the same manuscript* a copy at the request <and at the order> of the victorious, Abū-nasr son of Mard-šād son of Šāhpuhr who <was> from the blessed land of Šīrāz … IFootnote 68 wrote in Avestan with details, sections by sections and chapters by chapters, as it seemingly appears better, <more precise> and superior … <and> I wrote with as many <explanations> and commentaries as I could for recalling and remembering the last day and (for) happiness and ease <and pleasure> and the goodness of heaven.”Footnote 69

In Mazdapour's interpretation, Māhwindād Narmāhān was a figure whose name was attested in a manuscript. Mazdapour's inclusion of more texts from the Introduction into the (second) colophon is an important suggestion, although the detailed discussion of her proposal is beyond the scope of the present article as noted before.Footnote 70 But this much can be said, that her suggestion makes it even more likely that the occurrences of nibišt in the above text are to be taken as verbs governing the subject “I, Māhwindād Narmāhān”. As stated above, Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 323–4) showed that the Pahlavi language of the third colophon in Mf4, which was also written by Hōšang, is late. This evidence casts doubt on the suggestions that the entire Introduction including the above section, which according to Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 323–4), represents the ninth–tenth century Pahlavi at its latest, had also been written by Hōšang.

As a result, following Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 37), I regard the second colophon (and the Introduction) to be a work of Māhwindād Narmāhān, the scribe of the second colophon, while the first one belongs to Hōšang. I should also add that it is certain from Māhwindād's other (long) colophon in the manuscript B of the Dēnkard, that he lived in the early eleventh century ce,Footnote 71 a date that agrees with Tavadia's approximate dating of the Introduction.

5.2 Name of the creator of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript and the point of transition between the first and second colophon

West (Reference West1896–1904: 85) and Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115) consider Farrbay Srōšayār to be the scribe of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript. By contrast, Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 325) and Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 81) take Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd as the producer of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript. Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36–7) suggest that the first Pahlavi Yasna was a production of Māhayār Farroxzād. It should also be noted that the studies of Tavadia and Mazdapour have regrettably not been taken into consideration in the analysis of Cantera and de Vaan. While it is obvious from the text itself that Hōšang, either directly or indirectly, copied Mihrābān's manuscript which itself was a copy of Māhpanāh's codex, the relationship between Māhpanāh Āzādmard and Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd is disputed. The name of māhpanāh ī āzādmard is followed in lines 4–7 by ī panāh ī az kāzerōn rōstāg … rōstahm ī dād-ohrmazd “the protector from the region of Kāzerōn … Rōstahm son of Dād-Ohrmaz”. The phrase panāh ī az kāzerōn rōstāg … is associated with Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd by West and also by Dhabhar, through the insertion of “son of” after Māhpanāh Āzādmard:

Pt4 (3v4) … māhpanāh ī āzādmard

ī (5) panāh ī az kāzerōn rōstāg

čiyōn mard nēk (6) abarmāndīg

pad dēn ud ruwān abēgumān

u-š kāmag (7) frārōn ō yazdān wehān

rōstahm ī dād-ohrmazd (8) nōgdraxt

ī az farrox būm ī spāhān az rōddašt (9) rōstāg az warzanag deh

“(4) … Māh-panāh, son of Āzhāt̰.mart̰,

son of (5) the protector of so manyFootnote 72 from the district of Kāzherūn,

a beneficent man (6–7) superintending

in the religion, without doubt of the soul,

and his virtuous desire was for the sacred beings and the good,

(who was), Rūstakhm, son of Dāt̰- Aūharmazd, (8–9) a new plant

from the happy land of Ispāhān, from the town of VardshūkFootnote 73 of the Rūt̰-dasht district.” (West Reference West1896–1904: 85)Footnote 74

“(4) … Mahpanah Azadmard,

(son) of (5–7) the protector of so many (chandîn) from the district of kazherun-

a virtuous and distinguished man,

without doubt of the religion and the soul,

and of a virtuous desire for the Yazads and the good

viz., Rustom, Dâd-Auharmazd, (8–9) NaodarakhtFootnote 75

of the happy land of Ispahan, and of the town of Varjuk of the Rut-dasht district.” (Dhabhar Reference Dhabhar1923: 115)

Slightly different and with the addition of “(son) of” before Rōstahm son of Dād-Ohrmazd, Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36) also suggest that Rōstahm was the grandfather of Māhpanāh Āzādmard:

“(4) … Māhpanāh, son of Āzādmard,

(5) protector of the region of Kāzerōn

like a good (6–7) heir (?),

without doubt about religion and soul

and with honest desire for the good gods

(son of) Rōstahm, son of Dād-Ohrmazd, (8–9) Nōgdraxt

from the blessed land of Spāhān, from the town of Waržuk (?) in the Rūd-Dašt region.”

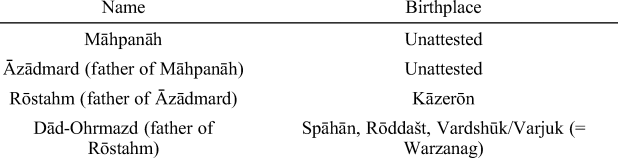

While “(son) of” in the ad hoc translation of Cantera and de Vaan has no corresponding word in the same position of its Pahlavi original, West and Dhabhar probably interpreted that the second ī (line 4) in māhpanāh ī āzādmard ī panāh expresses the possessive relationship between Māhpanāh Āzādmard and Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd. Their suggestions regarding the relationships between and birthplaces of Māpanāh, Āzādmard, Rōstahm and Dād-Ohrmazd are summarized as follows:

(i) The model of West and Dhabhar

(ii) The model of Cantera and de Vaan

The theories of West, Dhabhar, and Cantera and de Vaan rely on the assumption that a certain father and son came from two different unrelated places, that is, Kāzerōn (in the province of Bīšāpuhr in Pars) and the town of Warzanag, the region of Rōddašt in Spāhān, respectively. Furthermore, their theories fail to explain why it was important to provide the details of the birthplace(s) of figures who had no role in the production of the manuscripts. A more likely interpretation, however, is that the second ī is the relative pronoun and connects Māhpanāh Āzādmard with its descriptors panāh ī az kāzerōn rōstāg….Footnote 76 Therefore, it seems that there is no relationship between Māhpanāh Āzādmard and Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd. Rather, the latter belongs to the second colophon and is the subject of the verb nibišt ēstād “had written” in line 11 as discussed below in section 6. Therefore, the present article provides further support for the view put forward by Tavadia and Mazdapour about the producer of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript.

5.3 Producer of the Avestan and Pahlavi sources of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript

The second colophon also informs us that the Avestan and Pahlavi texts of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript were put together from two different manuscripts. According to West (Reference West1896–1904: 85), Māhayār Farroxzād and Māhwindād Narmāhan are the respective scribes of the Avestan and Pahlavi manuscripts. In Tavadia's (Reference Tavadia1944: 325) translation, the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript was produced by combining an Avestan manuscript and a copy of its Pahlavi version written by Māhayār Farroxzād and Farrbay Srōšayār, respectively. Likewise, Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 81) takes Farrbay Srōšayār to be the scribe of the Pahlavi manuscript; but unlike Tavadia, she suggests that the name of the scribe of the Avestan manuscript is absent from the colophon. In contrast, Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115) and Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36) suggest that the name(s) of the scribe(s) is(are) not attested. The investigation of the present study confirms the suggestions of Mazdapour.

6. Text of the second colophon

In this section, the translation of the verb nibišt ēstād, the role of the Pahlavi sign  in abestāg az paččēn-

in abestāg az paččēn-  ud zand az paččēn-

ud zand az paččēn-  and the meanings of xwēš rāy and jādag are investigated.

and the meanings of xwēš rāy and jādag are investigated.

6.1 Active or passive translation of the verb nibišt ēstād

Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36), translate the verb nibišt ēstād as passive:

“The Abestāg has been written from one copy and the Zand from one (other) copy for the possession of the immortal Farnbay,Footnote 77 son of Srōšayār, as a production (?) of the immortal Māhayār, son of Farroxzād, from the same salubrious district from the region of Kāzerōn.”

This interpretation is problematic because it fails to take into account that it was common in both Pahlavi and New Persian to omit the direct object, in the present context presumably ēn paččēn/nibēg “this copy”, in active sentences governed by the verb nibištan “to write”. According to the interpretation presented here, and also according to Cantera and de Vaan, Māhwindād Narmāhān was the scribe of the second colophon. He has another colophon attested in the manuscript B of the Dēnkard in which he uses a comparable active sentence with the verb nibišt ēstād, and here the form is to be interpreted in the active sense, with ellipsis of the direct object:

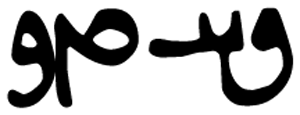

DkMFootnote 78 (946 line 18) … nibišt ēstād man māhwindād ī (19) narmāhān ī wahrām mihrābān

rōz ī dēn māh tīr pērōzgar ī (20) sāl 369

ī pas az sāl man ī ōy bay (21) yazdgird šāhān šāh ī šahryārān

stūrmānāg? xwēšīh ī xwēšīh (22) rāy …

“(18–19) … I, Māhwindād son of Narmāhān son of Wahrām Mihrābān, had written [this copy] on the day of Dēn, the month of the victorious Tīr of (20) the year 369 after the year of his majesty (21–22) Yazdgird, King of Kings, son of Šahryār,

like a guardian?, for my own possession ….”Footnote 79

Other examples include the beginning of the first colophon of YIrPs nibišt pad hamuskārišnīh pērōzgar man dēn bandag hōšang syāwaxš šahryār baxtāfrīd šahryār and the third Pahlavi colophon of Hōšang, which appears in Mf4:

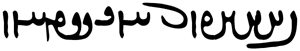

Mf4 (599 line 9) … man dēn bandag

hōšang syāwaxš šahryār ī (10) baxtāfrīd šahryār

ī wahrām ī husraw šāhag (11) anōšagruwān

nibišt ud frāz hišt xwēš ī (12) xwēš rāy

ud frazandān xwēš rāy …

“(9) … I, the servant of the religion,

Hōšang Syāwaxš Šahryār son of (10) Baxtāfrīd Šahryār,

son of Wahrām son of Husraw-Šāhag (11) Anōšagruwān

wroteFootnote 80 and published [this copy] for my (12) own possession,

and for (that) of my offspring ….”Footnote 81

This feature is also found in the colophon of J2 written down in ay 692 (1323 ce):

J2 (383v line 3) wahman māh frawrdīn rōz sāl ī 692 (4) yazdgirdīg

man dēn bandag hērbed zāt mihrābān (5) ī kayhusraw mihrābān

ī spendyār mihrābān marzb(ān) (6) hērbed nibišt

pad yazdān kāmag bād

(7) wahīzag kē man dēn bandag be būm hindūgān mad ham

andar (8) sāl 692 yazdgirdīg

man dēn bandag hērbed zād (9) mihrābān ī kayhusraw ī mihrābān

ī spendyād ī mihrābān ī (10) marzbān hērbed nibišt

az bahr čāhilag sangan

ud čāhil ī wahm(an) (11) bahrām kambaytīg nibišt …

“(3) On the day Wahman, month Frawardīn, year 692 (4) of Yazdgird,

I, the servant of the religion, Hērbed-born Mihrābān (5) son of Kayhusraw Mihrābān

son of Spendyār Mihrābān Marzb(ān) (6) Hērbed wrote [this copy].

May it be according to the will of Yazds.

(7) It was in the movable month that, I, the servant of the religion, came to the land of Indians.

In (8) the year 692 of Yazdgird,

I, the servant of the religion Hērbed-born (9) Mihrābān son of Kayhusraw son of Mihrābān

son of Spendyād son of Mihrābān son of (10) Marzbān Hērbed wrote [this manuscript],

for the sake of Čāhil Sangan

and Čāhil son of Wahm(an) (11) Bahrām of Cambay. I wrote….”Footnote 82

As for the New Persian colophons, in the following text from the Dārāb Hormazyār Rivāyat (Unvala Reference Unvala1922), written by Hōšang Syāwaxš Šhahryār, the verb neveštam (نوشتم)Footnote 83 “I wrote” occurs four times in lines 7, 8, 12 and 15, and governs the direct object, in (= Pahlavi ēn) “this”, only once in line 12:

DHR,Footnote 84 II (p. 368 line 7) نوشتم من دین بنده هوشنگ سیاوخش و شهریار بخت آفرید بهرام خسرو شاه

(8) انوشیروان نوشتم اندر فرخان بوم شرف آباد …

(12) … این نوشتم فه روز مانثرسفند ماه

(13) مهر سال هفت صد و چهل و هفت پارسی

(14) پس از یزدجرد شاهان شاه

(15) نوشتم

DHR, II (p. 368 line 7) neveštam man din bande hušang i syāwaxš o šharyār i baxt-āfrid i bahrām i xosraw šāh i

(8) anušerovān neveštam andar farroxān bum i šarafābād ….

(12) … in neveštam fe ruz i mānsarasfand māh i

(13) mehr sāl i haft-sad o čehel o haft i pārsi

(14) pas az yazdjerd i šāhān šāh

(15) neveštam

“(7–8) I, the servant of the religion Hušang Syāvaxš and? Šahryār Baxt-āfrīd Bahrām Xosrawšāh Anušerovān wrote. I wrote in the blessed land of Šarafābād …

(12) …. I wrote this on the day of Mānsarasfand, the month

(13) Mehr, the year seven hundred and forty-seven Pārsi,

(14) after Yazdjerd, King of Kings.

(15) I wrote.”Footnote 85

As in this last example, the active neveštam “I wrote” without a direct object also occurs in the Dārāb Hormazyār Rivāyat, p. 371, lines 3, 4 and 5:

DHR, II (p. 371 line 3) … باوستا نوشتم من دین بنده هوشنگ سیاوخش شهریار وهرام خسروشاه نوشوربان

(4) نوشتم پراج هشت اج پچین جاماسپ شهریار بختافرید … از خویشیم

(5) پیروزگرتران هیربدان دین پرورتاران دین آگاهان نوشتم …

DHR, II (p. 371 line 3) … be-avestā neveštam man din bande hušang i syāvaxš i šahryār i vahrām i xosraw šāh i nušorobān

(4) neveštam parāj hešt aj paččin i jāmāsp i šahryār i baxtāfrid … az xiš-yam

(5) piruzgartarān hirbedān din-parvartārān din-āgāhān neveštam …

“(3) … I, the servant of the religion, Hušang Syāvaxš Šahryār Vahrām Xosrawšāh Nōšerobān wrote in Avestan.

(4) I wrote, published [it] from the copy of Jāmāsp Šahryār Baxtāfrīd …. From my own expenses,

(5) I wrote for the more victorious Hirbeds, the religion-propagators [and] the religion-wise [men] ….”Footnote 86

On this basis, it is justified to take nibišt ēstād in the second colophon of the Introduction to the Iranian Pahlavi Yasna as a verb implying an object rather than expressing it explicitly.

6.2 Pahlavi sign  in (lines 9–10) abestāg az paččēn-ē ud zand az paččēn-ī “the Avesta from a copy and the Zand from the copy of”

in (lines 9–10) abestāg az paččēn-ē ud zand az paččēn-ī “the Avesta from a copy and the Zand from the copy of”

Regarding the Pahlavi signs  after abestāg az paččēn and zand az paččēn, each can be taken as either the ezāfa ī “of” or the indefinite article -ē. West (Reference West1986–1904: 84–5), Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115) and Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36) opt for the latter possibility and translate the phrase as “Avesta from one copy and the Zand from another copy”.Footnote 87 With the interpretation of the Pahlavi sign as indefinite, Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115) and Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36) assume that the respective names of the scribes of the two separate Avestan and Pahlavi manuscripts are not mentioned. In contrast, West (Reference West1896–1904: 85) suggests that abestāg az paččēn-ē “the Avesta from one copy” and zand az paččēn-ē “the Zand from another copy” were the productions of Māhayār Farroxzād and of Māhwindād Narmāhān Wahrām Mihr(ābān), respectively:

after abestāg az paččēn and zand az paččēn, each can be taken as either the ezāfa ī “of” or the indefinite article -ē. West (Reference West1986–1904: 84–5), Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115) and Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36) opt for the latter possibility and translate the phrase as “Avesta from one copy and the Zand from another copy”.Footnote 87 With the interpretation of the Pahlavi sign as indefinite, Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115) and Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36) assume that the respective names of the scribes of the two separate Avestan and Pahlavi manuscripts are not mentioned. In contrast, West (Reference West1896–1904: 85) suggests that abestāg az paččēn-ē “the Avesta from one copy” and zand az paččēn-ē “the Zand from another copy” were the productions of Māhayār Farroxzād and of Māhwindād Narmāhān Wahrām Mihr(ābān), respectively:

“the Awesta from one copy, and the Zand from another copy, (which were) the production of the glorified Māhyār, son of Farukhzāt̰, from the same salubrious place of the district of Kāzherūn, (and of) me, the immortal Māh-vindāt̰ son of Naremāhān, son of Vāhrām, son of Mitrō(-āpān).”Footnote 88

Although West translates the Pahlavi sign  as the indefinite article rather than the ezāfa ī “of”, he hypothetically associates the manuscripts with their suggested scribes by adding “which were” in round brackets. Later, Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1949: 7) sides with West by stating in the Introduction to his Pahlavi Yasna and Visperad that “Farnbag wrote his MS from two separate copies: 1) the Avesta text from the MS of Mahyar Farrukhzad; and 2) the Pahlavi text from the MS of Mahvindad Naremahãn Behram Meheravan”.

as the indefinite article rather than the ezāfa ī “of”, he hypothetically associates the manuscripts with their suggested scribes by adding “which were” in round brackets. Later, Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1949: 7) sides with West by stating in the Introduction to his Pahlavi Yasna and Visperad that “Farnbag wrote his MS from two separate copies: 1) the Avesta text from the MS of Mahyar Farrukhzad; and 2) the Pahlavi text from the MS of Mahvindad Naremahãn Behram Meheravan”.

A different interpretation is put forward by Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 325), who reads the Pahlavi sign  as the ezāfa ī “of”:

as the ezāfa ī “of”:

“Rōstaxm ī Dātōhrmazd had written the Apastāk from the copy of the [blessed Dātak [ī] Māhayār ī Farroxvzāt …] and the Zand from the copy of the blessed Farnbaγ ī Srōšayār for himself.”Footnote 89

Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 330) suggests that a scribe might have forgotten to write dādag Footnote 90 anōšag ruwān māhayār farroxzād after abestāg az paččēn ī. Therefore, he added the name of the scribe in the margin. Later, according to Tavadia, the second scribe misplaced it after nibišt ēstād.

However, from the syntactic point of view, the reading of the Pahlavi sign  as the ezāfa ī after abestāg az paččēn is problematic because in a nominal construction, the ezāfa ī must be directly followed by the noun or adjective which it connects to the preceding noun.Footnote 91 In our text, the name of Māhayār Farroxzād, in whom Tavadia (with West) sees the scribe of the Avestan manuscript, appears several words after abestāg az paččēn. Tavadia therefore tries to explain the irregular position of Māhayār Farroxzād with the entirely hypothetical and unlikely suggestion summarized above.

as the ezāfa ī after abestāg az paččēn is problematic because in a nominal construction, the ezāfa ī must be directly followed by the noun or adjective which it connects to the preceding noun.Footnote 91 In our text, the name of Māhayār Farroxzād, in whom Tavadia (with West) sees the scribe of the Avestan manuscript, appears several words after abestāg az paččēn. Tavadia therefore tries to explain the irregular position of Māhayār Farroxzād with the entirely hypothetical and unlikely suggestion summarized above.

In contrast, Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 75) takes the sign  after abestāg az paččēn as the indefinite article -ē and the second one after zand az paččēn as the ezāfa -ī. Her proposal is convincing because the word order of the Pahlavi text is then correct, straightforward and requires no insertion of hypothetical words in brackets to make the translation meaningful. Moreover, it is supported by the discussion set out in section 6.3. Therefore, associating the second

after abestāg az paččēn as the indefinite article -ē and the second one after zand az paččēn as the ezāfa -ī. Her proposal is convincing because the word order of the Pahlavi text is then correct, straightforward and requires no insertion of hypothetical words in brackets to make the translation meaningful. Moreover, it is supported by the discussion set out in section 6.3. Therefore, associating the second  with Farrbay Srōšayār, I read the phrase as abestāg az paččēn-ē ud zand az paččēn-ī anōšag farrbay srōšayār “the Avesta from a copy and the Zand from the copy of the immortal Farrbay Srōšayār”.

with Farrbay Srōšayār, I read the phrase as abestāg az paččēn-ē ud zand az paččēn-ī anōšag farrbay srōšayār “the Avesta from a copy and the Zand from the copy of the immortal Farrbay Srōšayār”.

6.3 Meaning of xwēš rāy (lines 10–11)

Both West (Reference West1896–1904: 85) and Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115) considered Farrbay son of Srōšayār to be the scribe of the first bilingual Pahlavi Yasna manuscript. This is indicated by the way they translate lines 9–11:

abestāg az paččēn-  ud zand az paččēn-

ud zand az paččēn-  Footnote 92 anōšag farrbay srōšayār xwēš rāy nibišt ēstād

Footnote 92 anōšag farrbay srōšayār xwēš rāy nibišt ēstād

“The immortal Farnbag, son of Srōshyār, had written a copy for himself- the Awesta from one copy, and the Zand from another copy,” (West Reference West1896–1904: 85).

“The immortal Farnbag Sroshyar had himself written a copy- the Avesta from one copy and the Zand from another copy-” (Dhabhar Reference Dhabhar1923: 115).

While West renders xwēš rāy as “for himself”, Dhabhar translates it as “himself”, thus leaving rāy untranslated. Like West, Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 325) and Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 81) translate xwēš rāy as “für sich” (for himself) and “برای خویش” (for himself), respectively. But unlike West (and Dhabhar), they associate the expression with Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd (line 7) whom they regard as the creator of the first known bilingual Avestan-Pahlavi manuscript. Their respective translations run as follows:

“Rōstaxm ī Dātōhrmazd … had written the Apastāk from the copy of … and the Zand from the copy of … for himself.”Footnote 93

“Rostahm <son> of Dād-Ohrmazd … had written the Avesta from a copy … and the Zand from the copy of … for himself.”Footnote 94

A possible objection to the translation of xwēš rāy as “for himself” could arise from the view put forward by Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 38), according to whom “the expression xwēš rāy usually serves to indicate the addressee or patron of the copy” in the texts. They accordingly translate anōšag farrbay srōšayār xwēš rāy as “for the possession of the immortal Farrbay son of Srōšayār”. Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 38) further support this interpretation with reference to the formula xwēšīh ī xwēš rāy “for his own possession” which is common in the colophons. They provide three examples:

MS K1 colophon 2: u-m ēn paččēn nibišt xwēšīh ī xwēš rāy abestāg ud zand …

“and I have written this copy for my own possession, Avesta and Zand”

MS M 51a nibišt xwēš <īh> ī xwēš rāy

“I have written for my own possession”

DkM 950.2 xwēšīh ī xwēš rāy ud frazandān ī xwēš rāy

“for his own possession and for the possession of his offspring.”

In translating xwēš as “possession”, Cantera and de Vaan confuse the meaning of the reflexive pronoun xwēš “self” with that of xwēšīh “possession” in their first and second examples.Footnote 95 With regard to the third example, quoted above, they claim that “one also finds the formula with a noun (here: frazandān) preceding xwēš”. As a result, they postulate the new meaning “for the possession of” for xwēš rāy. However, rather than postulating such a new meaning, it is more likely that xwēšīh ī has been omitted after ud owing to the ellipsis in their third example:

DkM 950.2 xwēšīh ī xwēš rāy ud frazandān ī xwēš rāy

“for his own possession and for (the possession of) his offspring.”

Therefore, with West, Tavadia and Mazdapour, it is preferable to translate xwēš rāy “for himself” in abestāg az paččēn-ē ud zand az paččēn-  anōšag farrbay srōšayār xwēš rāy nibišt ēstād.

anōšag farrbay srōšayār xwēš rāy nibišt ēstād.

Two candidates can be considered for the subject of the verb nibišt ēstād, and for the person to whom the reflexive pronoun xwēš refers. One possibility is Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd, the other is Farrbay Srōšayār in the sentence:

Pt4 (3v7) … rōstahm ī dād-ohrmazd (8) nōgdraxt

ī az farrox būm ī spāhān az rōddašt (9) rōstāg az warzanag deh

abestāg az paččēn-ē (10) ud zand az paččēn-

anōšag farrbay srōšayār xwēš (11) rāy nibišt ēstād

The following arguments speak in favour of the interpretation that Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd is the subject of the verb:

1) As argued in section 5.2, the suggestion of West, Dhabhar, and Cantera and de Vaan that Rōstahm was the grandfather of Māhpanāh is unlikely. Unless Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd is the subject of the verb, he has no function in the sentence.

2) The sentence starting with Rōstahm Dad-Ohrmazd follows the correct SOVFootnote 96 syntax of Pahlavi. It means that Rōstahm Dad-Ohrmazd had written [a copy] for himself, the Avesta from one copy (abestāg az paččēn-ē) and (ud) the Zand from the copy of the immortal Farrbay Srōšayār (zand az paččēn-ī anōšag farrbay srōšayār). The translation should therefore be as follows:

“Rōstahm, son of Dād-Ohrmazd Nōgdraxt from the blessed land of Spāhān, from the Rōd-Dašt region, from the town of Warzanag, had written [a copy] for himself, the Avesta from a copy and the Zand from the copy of the immortal Farrbay Srōšayār.”

6.4 Meaning of jādag (line 11)

After zand az paččēn-ī anōšag farrbay srōšayār xwēš rāy nibišt ēstād, the text continues as follows:

Pt4 (3v11–13)jādag anōšag ruwān māhayār ī farroxzād ī az ham bīšāpuhr awestān az kāzerōn rōstāg.

The reading and translation of  (jādag) is debated among scholars. West (Reference West1896–1904: 84–5) reads it as dʾtk and interprets the word as meaning “production”. Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 329–30) also eventually resolves to read the word as dādag, but interprets it as the personal name “Dātak [ī] Māhayār ī Farroxvzāt”. The possibly related Pahlavi word dādagīh (or jādagīh) occurs in IrBd. 35A.8Footnote 97 ud man farrbay ī xwānēnd dādagīh ī ašawahišt “and I Farrbay whom they call Dādagīh son of Ašawahišt”; but its interpretation as a personal name has been refuted by Mackenzie (1989: 548), who prefers the reading jādagīh and sees in it an honorary epithet meaning “apportionment”.

(jādag) is debated among scholars. West (Reference West1896–1904: 84–5) reads it as dʾtk and interprets the word as meaning “production”. Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 329–30) also eventually resolves to read the word as dādag, but interprets it as the personal name “Dātak [ī] Māhayār ī Farroxvzāt”. The possibly related Pahlavi word dādagīh (or jādagīh) occurs in IrBd. 35A.8Footnote 97 ud man farrbay ī xwānēnd dādagīh ī ašawahišt “and I Farrbay whom they call Dādagīh son of Ašawahišt”; but its interpretation as a personal name has been refuted by Mackenzie (1989: 548), who prefers the reading jādagīh and sees in it an honorary epithet meaning “apportionment”.

As rightly noted by Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 38), dādag is an otherwise unknown word. The interpretation jʾtk /jādag/ is therefore to be preferred. The reading jādag is also supported by T54 (fol. 3v line 2), G14 (fol. 19v line 11) and T6 (fol. 7r line 5), which place a dot beneath the Pahlavi sign  in

in  .Footnote 98 This interpretation was already adopted by Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115, fn. 6) and Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 75, 82) who posit the meaning “for the sake of, for the preserving of the memory of”.Footnote 99 Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 38) also transliterate jʾtk but translate it as “production”. Although West, and Cantera and de Vaan both translate the Pahlavi word as “production”, their respective contextual interpretations differ. While West considers the Avestan source of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript to have been produced by Māhayār Farroxzād, according to Cantera and de Vaan, Māhayār Farroxzād produced the first combined Avestan-Pahlavi Yasna manuscript.

.Footnote 98 This interpretation was already adopted by Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115, fn. 6) and Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 75, 82) who posit the meaning “for the sake of, for the preserving of the memory of”.Footnote 99 Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 38) also transliterate jʾtk but translate it as “production”. Although West, and Cantera and de Vaan both translate the Pahlavi word as “production”, their respective contextual interpretations differ. While West considers the Avestan source of the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript to have been produced by Māhayār Farroxzād, according to Cantera and de Vaan, Māhayār Farroxzād produced the first combined Avestan-Pahlavi Yasna manuscript.

While West, Dhabhar, Mazdapour, and Cantera and de Vaan do not examine the word in greater detail, Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 329–30), who first considers but then rejects the reading jādag, Footnote 100 provides a detailed study of it. He notes that the corresponding Pahlavi jādagīh ī man and the Zoroastrian New Persian man jāda rā and jāda i man rā mean “for me, for my share”, and this especially in association with the prayers of penitence after death. For example, the variant jādagīh occurs in the third colophon of Mf4, written by Hōšang:

Mf4 (p. 599 line 12) har kē (13) xwānād

ayāb hammōzād ayāb paččēn az-iš (14) kunād

jādagīh ī man nibištār pad patet bawēd

“(12) Everyone who reads [it],

or teaches [it] or makes a copy of it,

(14) for me, the writer, will be in repentance.”Footnote 101

By translating jādag as “for, the share of”, the sequence of jādag anōšag ruwān māhayār ī farroxzād makes sense. The reason is that anōšag ruwān, the descriptor of māhayār ī farroxzād, could entail that the scribe wrote the manuscript “for (the penitence of) the immortal souled (= deceased)” Māhayār Farroxzād.Footnote 102 Therefore, the first Pahlavi Yasna manuscript was written for its creator, Rōstahm Dād-Ohrrmazd, and Māhayār Farroxzād. It should be noted that a particular manuscript could have been written for more than one person, for example, the Indian Pahlavi manuscripts J2 and K5 written by Mihrābān Kayhusraw.Footnote 103

7. The reading of  as bīšāpuhr and the honorary title anōšag preceding man māhwindād ī narmāhān ī wahrām mihr

as bīšāpuhr and the honorary title anōšag preceding man māhwindād ī narmāhān ī wahrām mihr

7.1 az ham bīšāpuhr awestān az kāzerōn rōstāg “from the same Bīšāpuhr province, from the region of Kāzērōn” (lines 12–13)

Reading bīšāpuhr awestān ( )Footnote 104 as bēšāžvārānistān, West (Reference West1896–1904: 84–5) translates the expression as “the salubrious place”, later followed by Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115–16). While Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 37, fn. 23) indicate that the form byšʾcwʾl is unknown elsewhere, they accept West's suggestion and follow his reading of

)Footnote 104 as bēšāžvārānistān, West (Reference West1896–1904: 84–5) translates the expression as “the salubrious place”, later followed by Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1923: 115–16). While Cantera and de Vaan (Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 37, fn. 23) indicate that the form byšʾcwʾl is unknown elsewhere, they accept West's suggestion and follow his reading of  with a slight emendation as bēšāzwār awestām “the salubrious district” (Cantera and de Vaan Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36–7). It should be noted that in contrast to what West suggests,

with a slight emendation as bēšāzwār awestām “the salubrious district” (Cantera and de Vaan Reference Cantera and de Vaan2005: 36–7). It should be noted that in contrast to what West suggests,  is separated from

is separated from  in the manuscripts.

in the manuscripts.

Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 325) translates  as Gau Vēhšāpuhr (the district of Vēhšāpuhr) and considers the Pahlavi spelling

as Gau Vēhšāpuhr (the district of Vēhšāpuhr) and considers the Pahlavi spelling  to be a late or corrupt form of Vēhšāpuhr (Tavadia Reference Tavadia1944: 338). This form actually occurs in the Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšahr,Footnote 105 although it seems to be incorrect (Sundermann Reference Sundermann1986: 294). While the corresponding (correct) spelling byš(ʾ)pwhr occurs on bullae, a seal and an inscription in Pahlavi, the variant byšʾpwhr agrees with the Pahlavi spelling of the colophon.Footnote 106 Therefore, Tavadia's reading is well supported. Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 81) also renders

to be a late or corrupt form of Vēhšāpuhr (Tavadia Reference Tavadia1944: 338). This form actually occurs in the Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšahr,Footnote 105 although it seems to be incorrect (Sundermann Reference Sundermann1986: 294). While the corresponding (correct) spelling byš(ʾ)pwhr occurs on bullae, a seal and an inscription in Pahlavi, the variant byšʾpwhr agrees with the Pahlavi spelling of the colophon.Footnote 106 Therefore, Tavadia's reading is well supported. Mazdapour (Reference Mazdapour1375/1996: 81) also renders  as “the province of Bīšābur”.

as “the province of Bīšābur”.

With Tavadia and Mazdapour, I am inclined to suggest that bīšāpuhr awestān is the correct reading. This suggestion is corroborated by three recently discovered Sasanian clay bullae of (a) Zoroastrian priest(s) from (the province of) Bīšāpuhr (byšpwhly), (the region of) Kāzerōn, which shows that Kāzerōn was a region in the administrative division of Bīšāpuhr (Ghasemi et al. Reference Ghasemi, Gyselen, Noruzi and Rezaei1396/2017: 94, 99). It should be noted that writers of the early Islamic period also state that Kāzerōn belonged to the administration of Bīšāpuhr (Ghasemi et al. Reference Ghasemi, Gyselen, Noruzi and Rezaei1396/2017: 101).

The anaphor ham, preceding bīšāpuhr, could hypothetically be interpreted in different ways:

1) Māhayār Farroxzād came from the same province whose name was in the mind of the scribe of the second colophon, Māhwindād Narmāhān, that is, his own unattested province.

2) As suggested by Tavadia (Reference Tavadia1944: 339), Mahayār Farroxzād could have been the brother of the famous Zoroastrian high priest of the ninth-century Adurfarrbay Farroxzādān. Assuming everybody knew Adurfarrbay Farroxzādān, ham bīšāpuhr could mean that Mahayār Farroxzād came from the same province as that of his brother.

3) The anaphor ham could have been a late insertion by Hōšang. According to this interpretation, ham refers back to Kāzerōn, the region of Māhpanāh Āzādmard, which had already been mentioned in the first colophon.

7.2 anōšag ī man māhwindād ī narmāhān ī wahrām mihr “I, the immortal Māhwindād son of Narmāhān son of Wahrām Mihr” (lines 13–14)

The honorary title anōšag “immortal”, occurs before man māhwindād “I, Māhwindād”, the scribe of the second colophon. However, in his colophon in the manuscript B of the Dēnkard, as mentioned in section 6.1, he simply refers to himself as man māhwindād ī narmāhān ī wahrām mihrābān. Therefore, the honorary title might have been inserted later by another scribe. This possibility is supported by the fact that scribes usually described themselves with modest titles such as dēn bandag “the servant of the religion”.

8. Text of the first colophon in T54 and the colophon of Kāyūs

In T54, the beginning of the first colophon runs as follows:

T54 (2v line 12) … ud ham čim rāy ī nibišt pad (13) hamuskārišnīh

pērōzgar man dēn bandag kāyūs (3r 1) pus dastwar suhrāb

pus dastwar rōstam (2) pus dastwar mānōg

pus dastwar mihrānōš pus (3) dastwar kay-kawād

pus dastwarān dastwar ī (4) māhayār rānān

andar bilād ī hindūgān Footnote 107 sākon ī kasabag ī nōg sārīg

(5) az paččēn hērbed hōšang syāwaxš šahryār (6) baxtāfrīd šahryār …

“(2v line 12) and for this reason, (I) wrote [this copy] with (13) the inspiration of

the victorious [Yazds], I, the servant of the religion, Kāyūs (31r line 1) son of the priest Suhrāb,

son of the priest Rōstam, (2) son of the priest Mānōg,

son of the priest Mihrānōš son of (3) the priest Kay-Kawād,

son of the priest of priests (4) Māhayār Rānān

in the lands of Indians, resident of the town of Nōg Sārīg [=Nawsāri]

(5) from the manuscript of the priest Hōšang Syāwaxš Šahryār (6) Baxtāfrīd Šahryār.”

The additional text in T54, which is absent from all other manuscripts, is inserted between man dēn bandag “I the servant of the religion” and (hērbed) hōšang. Footnote 108 The text in T54 continues as in the other manuscripts with the minor variations as collated in section 4. The following table summarizes the difference between the text of the first colophon in T54 and Pt4 (3r21–3v3). Phrases that are identical in T54 and Pt4 are set in bold characters:

In T54, the first-person pronoun man “I” is associated with Kāyūs rather than with Hōšang.Footnote 109 Dhabhar (Reference Dhabhar1949: 6) had stated that Kāyūs “has incorporated his name in the long colophon given at the beginning by the original writer Hoshang Siyavakhsh”. That the additional text in T54 (Kāyūs's text) has been inserted into the original colophon of Hōšang by Kāyūs is indicated by the Arabic loan words bilād “lands”, sākon “resident” and kasabag “town” in Kayūs's text (fol. 3r line 4). Elsewhere in the two colophons, the Pahlavi words rōstāg “region”, deh “town” and būm “land” are used to refer to geographical locations and there is only one Arabic personal name, Abunasr.

In G14, the story of the compilation of Kāyūs's (= Kāwūs in G14 and T6) manuscript is also given with three major differences:

1) Kāwūs's text appears as a separate colophon at the end of the second part of the Introduction, as noted in section 2.

2) The completion date of Kāwūs's manuscript, ay 1149 (1780 ce), is provided in the colophon.

3) Kāwūs appears as the third person:

G14 (21r line 6) ud ēn daftar fradom andar hindūgān

dastwar kāwūs (7) pus dastwar suhrāb

pus dastwar rōstam pus dastwar mānak

(8) pus mihrnōš az pušt ī māhayār rānān

andar kasabak ī nōg sārīg

(9) andar rōz hordād ud māh ī farrox frawardīn

sāl abar 114- (10) 9 yazdgirdīg šāhān šāh ī ohrmazdān nibišt ēstād

az (11) abar ō ōy nibēsēd xub frazām kāmag hanjām bawād

pad (12) yazdān ayārīh

“(6) And this manuscript first [was written] in India.

The priest Kāwūs (7) son of the priest Suhrāb

son of the priest Rōstam son of the priest Mānak

(8–10) son of Mihrnōš a descendant of Māhayār Rānān

had written [it] in the town of Nōg Sārīg

on the day Hordād and the blessed month Frawardīn,

the year 1149 of Yazdgird, King of Kings, a descendant of Ohrmazd.

From [it] (11) [who] writes for him, may he be of good fortune [and] successful

through (12) the assistance of the Yazds.”

Therefore, the completion date in the third colophon of the manuscript G14 must refer to that of the original manuscript of Kāyūs rather than to that of G14. As a result, G14 is an undated copy since it cannot be a production of Kāyūs in 1780 ce. The following pieces of evidence corroborate that T54 is as old as Pt4 and Mf4 and suggest that, completed in 1780 ce by Kāyūs, T54 was probably the direct or indirect source of G14:

1) Although the name and colophon of Kāwūs are absent from Pt4, according to the family tradition of its owner, the manuscript was written by Dastur Kāvasji Sohrābji Mihirji-rānā (Geldner Reference Geldner1896: Prolegomena xiii).

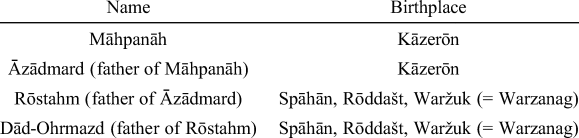

2) According to Dhabhar's (Reference Dhabhar1949: 6) observation, T54 is very close to Pt4. My preliminary comparison of the Pahlavi version of the manuscripts also confirms that in cases of significant variant orders between Pt4-Mf4 on the one hand, and G14-T6 on the other hand, T54 agrees with Pt4-Mf4. For example, the order of the Avestan original xvarənaŋvhastəmō zātanąm huuarə.darəsō maṣ̌iiānąm and the Pahlavi version of huuarə.darəsō maṣ̌iiānąm, occurring in Yasna 9.4, varies between the manuscripts Pt4-Mf4-T54 and G14-T6:

Another example of such different orders between the manuscripts is observed in Y 9.11 (data not shown).

3) The quality of the text of the colophons in T54 exceeds that of its related copies of the Kāyūs family, that is, G14 and T6, as discussed in the following section.

9. Variant readings of the geographical locations, personal names and the first-person pronoun man “I” preceding māhwindād in G14 and T6

As far as the geographical origin of scribes is concerned, according to Pt4, Mf4 and T54 they come from the central and western parts of Iran:

Hērbed Māhpanāh Āzādmard: kāzerōn rōstāg “the region of Kāzerōn”

Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd: būm ī spāhān, rōddašt rōstāg, warzanag deh “the land of Spāhān, the Rōd-Dašt region, the town of Warzanag”

Māhayār Farrōkhzād: bīšāpuhr awestān kāzerōn rōstāg “the province of Bīšāpuhr, the region of Kāzerōn”

Abu-Nasr Mardšād: būm ī šīrāz “the land of Šīrāz”.

In G14 (19v line 12), kʾclwn “Kāzerōn” is spelled as kʾp̄uhl “Kabul?”:

az ham bīšāpuhr awestān az kābul? Rōstāg (Māhayār Farroxzād came) from the same Bīšāpuhr province, from the region of Kābul?

However, while it is obvious that Bīšāpuhr and Kābul are geographically unrelated, the expected spelling of Kabul is kʾp̄wl. With the reading of G14, it might be possible to associate kābul with the following anōšag ī man māhwindād “I the immortal Māwindād”, the scribe of the second colophon. This suggestion is also unlikely because Māhwindād has another colophon in the manuscript B of the Dēnkard in which he states that he copied the Dēnkard from a copy that he had found in Baghdad.Footnote 121 It stands to reason then that he came from somewhere in Mesopotamia or environs west of the Iranian plateau.

In T6, which also provides the interlinear New Persian translation of the colophon text, more cities are identified with those in eastern Iran:

Hērbed Māhpanāh Āzādmard: T6 (fol. 6v line 13)  “Kāzerōn” (in the New Persian version ﻜﺎﺑﻮﻞ “Kabul”).

“Kāzerōn” (in the New Persian version ﻜﺎﺑﻮﻞ “Kabul”).

Māhayār Farrōkhzād: T6 (fol. 7r line 6) ham nēšāpur xujestān Footnote 122 (![]() ). Moreover, T6 (7r line 6) writes

). Moreover, T6 (7r line 6) writes  ? Likewise,

? Likewise, ![]() is translated in the interlinear New Persian version as ham nēšāpur xujestān az kābul (ﻫﻢ ﻨﻴﺸﺎﭙﻮﺭﺨﻮﺠﺴﺘﺎﻦ از کابل) “from Nēšāpur Xujestān from Kābul”, both of which, nēšāpur and xujestān, are located in Khorasan.Footnote 123

is translated in the interlinear New Persian version as ham nēšāpur xujestān az kābul (ﻫﻢ ﻨﻴﺸﺎﭙﻮﺭﺨﻮﺠﺴﺘﺎﻦ از کابل) “from Nēšāpur Xujestān from Kābul”, both of which, nēšāpur and xujestān, are located in Khorasan.Footnote 123

Like G14, the text of T6 seems to be subject to re-interpretation according to the scribe's mindset. The reason for this is that in fol. 6v line 13, the word in the Pahlavi version is spelled apparently as kʾclwn' /kāzerōn/, while in the New Persian version ﻜﺎﺑﻮﻞ “Kabul” is given. Furthermore,  ? “Kābul?” in fol. 7r line 6 is probably the corrected variant of the original

? “Kābul?” in fol. 7r line 6 is probably the corrected variant of the original  . In G14 (fol. 19v lines 5–6), T6 (fol. 6v line 12), the name of the famous scribe mihrābān spendyād mihrābān (= mihrābān spendyār mihrābān in J2) is also replaced by kē ābān spendād kē ābān “who is Ābān Spendāt who is Ābān?”:

. In G14 (fol. 19v lines 5–6), T6 (fol. 6v line 12), the name of the famous scribe mihrābān spendyād mihrābān (= mihrābān spendyār mihrābān in J2) is also replaced by kē ābān spendād kē ābān “who is Ābān Spendāt who is Ābān?”:

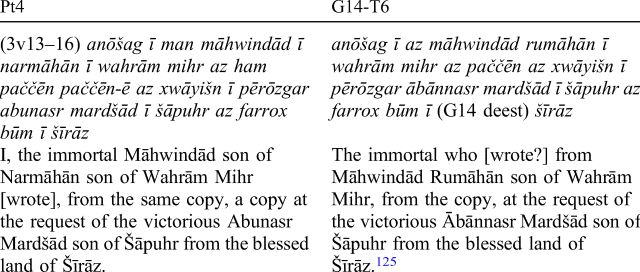

Pt4 (3v 1) … man dēn bandag hōšang (2) syāwaxš šahryār baxtāfrīd šahryār

az (3) paččēn hērbed mihrābān spendyād mihrābān (G14 T6: kē ābān spendād kē ābān)

“(1) I, the servant of the religion, Hōšang (2) Syāwaxš Šahryār Baxtāfrīd Šahryār,

[wrote this copy] from (3) the copy of hērbed Mihrābān Spendyād Mihrāban (G14 T6: who is Ābān Spendād who is Ābān).”

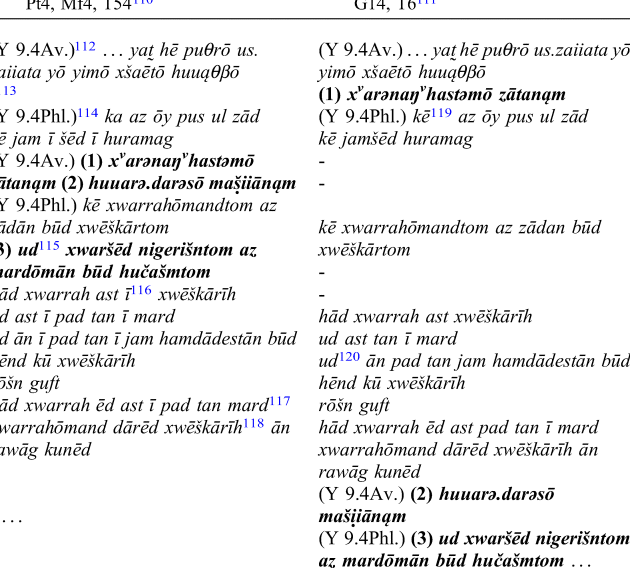

In addition, as collated above, G14-T6 write narmāhān and abunasr as rumāhān? and ābānnasr?Footnote 124, respectively, and tend to omit the relative pronouns.

As regards the Pahlavi sign  (= man), it precedes māhwindād ī narmāhān ī wahrām mihr in Pt4, Mf4 and T54. By contrast, in G14 (fol. 19v line 13) and T6 (fol. 7r line 6), it appears as

(= man), it precedes māhwindād ī narmāhān ī wahrām mihr in Pt4, Mf4 and T54. By contrast, in G14 (fol. 19v line 13) and T6 (fol. 7r line 6), it appears as  which can be transliterated either heterographically as MN (= az “from”) or eteographically as mn (= man “I”). The corresponding interlinear New Persian translation از “from” in T6 agrees with the former reading. Pt4 (3v14) az ham paččēn paččēn-ē az also appears as az paččēn az in G14-T6. The following table compares the concluding words in Pt4 with those in G14-T6:

which can be transliterated either heterographically as MN (= az “from”) or eteographically as mn (= man “I”). The corresponding interlinear New Persian translation از “from” in T6 agrees with the former reading. Pt4 (3v14) az ham paččēn paččēn-ē az also appears as az paččēn az in G14-T6. The following table compares the concluding words in Pt4 with those in G14-T6:

As shown above, the colophons in G14 and T6 have several corrections elsewhere. Furthermore, man … narmāhān … az ham paččēn paččēn-ē az rather than az … rumāhān … az paččēn az is present in their related manuscript T54, whose quality is superior to that of G14 and T6. Therefore, it is possible that the scribes of G14 and T6 corrected the spelling of  to

to  which frequently occurs in the colophons, and omitted (ham) paččēn-ē as it was thought to be erroneously repeated.

which frequently occurs in the colophons, and omitted (ham) paččēn-ē as it was thought to be erroneously repeated.

10. Conclusions

As regards the filiation of the second colophon, I have argued that Māhwindād Narmāhān copied the Pahlavi manuscript of Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd. The latter was the one who had combined a manuscript containing the Avestan text of the Yasna with another manuscript containing the Pahlavi version of the Yasna for himself and for the deceased Māhayār Farroxzād. I have also suggested that Farrbay Srōšayār was the scribe of the manuscript that was the source of the Pahlavi version of Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd's manuscript. Moreover, the second colophon shows that Rōstahm Dād-Ohrmazd, the scribe of the first known Pahlavi Yasna manuscript, was from Spāhān. Reading the debated  as bīšāpuhr awestān, I propose that Māhayār Farroxzād came from “the province of Bīšāpuhr”.

as bīšāpuhr awestān, I propose that Māhayār Farroxzād came from “the province of Bīšāpuhr”.

For the different filiation of the first colophon in T54, I have suggested in the present article that Kāyūs added his late text to the first colophon in which he described himself as the copyist of the manuscript of Hōšang. Moreover, among T54, G14 and T6 associating themselves with Kāyūs, the quality of the first is superior and closer to that of Pt4 and Mf4. Although the completion date of T54 is unattested in the manuscript, I have proposed that this date may be found in G14. The reason for this is that the Pahlavi colophon of G14, which is placed after the Introduction, declares that Kāwūs (= Kāyūs in T54) completed his copy in ay 1149 (1780 ce). However, Kāwūs must be considered as a historical figure in G14, since his name occurs in the third person in the colophon of this manuscript; also the quality of T54, in whose first colophon Kāyūs speaks, is closer to that of Pt4 which is traditionally considered to be written by Kāyūs.

in (lines 9–10) abestāg az paččēn-ē ud zand az paččēn-ī “the Avesta from a copy and the Zand from the copy of”

in (lines 9–10) abestāg az paččēn-ē ud zand az paččēn-ī “the Avesta from a copy and the Zand from the copy of” as bīšāpuhr and the honorary title anōšag preceding man māhwindād ī narmāhān ī wahrām mihr

as bīšāpuhr and the honorary title anōšag preceding man māhwindād ī narmāhān ī wahrām mihr

; G14 T6:

; G14 T6:  . Therefore, it can also be read as čandīn (cndyn') “many”.

. Therefore, it can also be read as čandīn (cndyn') “many”. .

. In the New Persian version, it is rendered as kābul (ﻜﺎﺑﻞ ).

In the New Persian version, it is rendered as kābul (ﻜﺎﺑﻞ ). represents ruwān (lwbʾn') and therefore, he does not discuss whether it is a corrupt form or an abbreviation of ruwān.

represents ruwān (lwbʾn') and therefore, he does not discuss whether it is a corrupt form or an abbreviation of ruwān. after abestāg az paččēn and zand az paččēn see section

after abestāg az paččēn and zand az paččēn see section  .

. ; T6 (7r6):

; T6 (7r6):  . Three diacritical dots are placed above

. Three diacritical dots are placed above  to indicate š.

to indicate š. , which precedes māhwindād, as mn /man/, a translation could be “I, the immortal Māhwindād Rumāhān son of Wahrām Mihr [wrote] from the copy at the request of the victorious Ābānnasr Mardšād son of Šāpuhr from the blessed land of Šīrāz”.

, which precedes māhwindād, as mn /man/, a translation could be “I, the immortal Māhwindād Rumāhān son of Wahrām Mihr [wrote] from the copy at the request of the victorious Ābānnasr Mardšād son of Šāpuhr from the blessed land of Šīrāz”.