No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

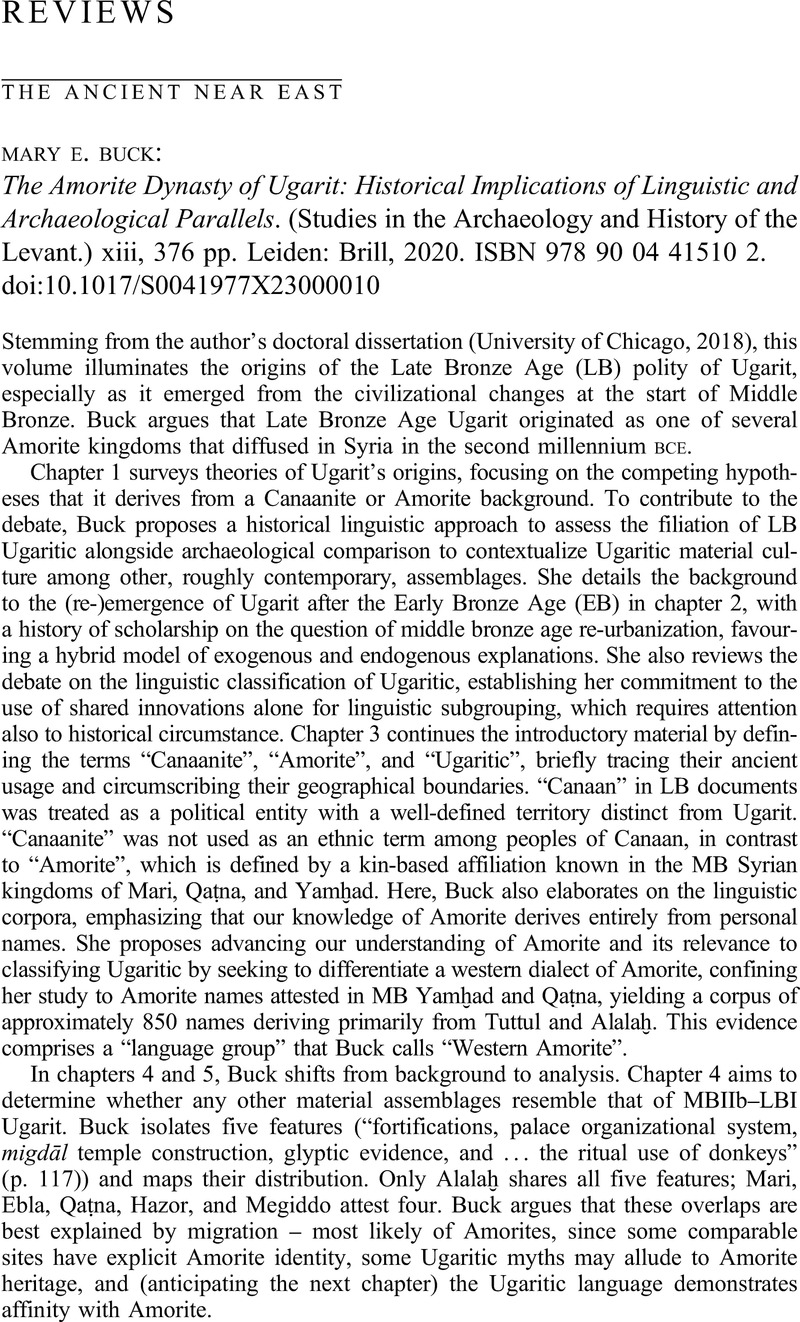

Mary E. Buck: The Amorite Dynasty of Ugarit: Historical Implications of Linguistic and Archaeological Parallels. (Studies in the Archaeology and History of the Levant.) xiii, 376 pp. Leiden: Brill, 2020. ISBN 978 90 04 41510 2.

Review products

Mary E. Buck: The Amorite Dynasty of Ugarit: Historical Implications of Linguistic and Archaeological Parallels. (Studies in the Archaeology and History of the Levant.) xiii, 376 pp. Leiden: Brill, 2020. ISBN 978 90 04 41510 2.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 March 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Reviews: The ancient Near East

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of SOAS University of London