Article contents

‘The Map of Hajji Ahmed’ and its Makers

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

Extract

This study owes its inception to Sir Percival David, who possesses among the treasures in his private collection one of the few surviving copies of a large engraved map of the world, known to students of cartography as the Map of Hajji Ahmed. Invited by its owner to translate for him the legends in the map and especially the lengthy text accompanying it, which are written in Turkish, I became aware that a close analysis of this text yielded more information than has so far been obtained about the origin of the map.

- Type

- Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1958

References

page 291 note 1 Sir Percival was good enough to place at my disposal a set of full-size photographs of another copy of the map (preserved in Venice), to lend me his copy of d'Avezac' article (see below), the only thorough published description, and to permit me to check doubtful readings in the photographs with his own very clear copy of the map. For this and for the fruitful discussions I have had with him I offer him my sincere thanks.

page 291 note 2 Older guide-books describe the blocks as being exhibited in the Sala dello Scudo in the Ducal Palace, for they were exhibited there as part of the collection of the Archaeological Museum from 1847 to 1924. They are now in a small room in the Libreria Vecchia, hanging beside the famous map of Fra Mauro.

page 291 note 3 The map itself in fact occupies only four blocks (see below, p. 293, n. 4).

page 291 note 4 While in Venice recently I saw one (catalogued Rari V 38) of the two copies of Pinelli' impression preserved at St. Mark' Library. On the back is written :

‘Impressione Comandata dall’ Ecelso Consiglio di Xcl di No. 7 (‘No.’ is crossed out and the ‘7’ altered to ‘6’) Tavole di Legno rappresentanti la superficie del Globo ritrovate nell’ Archivio Trib.le sudd0.

‘Copia di Articolo nella Scrittura de Soprintendente agl’ Archivi de' di 12. 7mbre 1795 : Prestatosi all' opera con lodevole disinteressatezza questo Pubblico Stampator Pinelli stimandosi abbastanza premiato per l’onor della Commissione, venne a risaltarne dall' union di qne' Fogli una completa Mappa rapptante la superficie intiere del nostro globo Terraqueo, e si è potuto con sorpresa riconoscere che i caratteri di essa Mappa erano tutti in lingua Turchesca.

‘Copia di Articolo di Decreto dell' Eccelso Consiglio di Xcl de' di 18. 7mbre 1795 : omissis Si rileva con compiacenza, che sia anche riuscito di rinvenire fra queste Carte la descritta Mappa in Lingua Turchesca incisa sopra varie tavolette, rappresentante la superficie del Globo, di cui si lauda, che ne abbia procurata la stampa e quindi l'ilhistrazione col mezzo del riputato Professore di Lingue Orientali Abbate Assemani, Predelibera, che abbia ad essere passato, e custodito l'originale autografo di detta Mappa nella Pub.ca Biblioteca, si assente, a seconda del suggerimento del N. H. Sopraint.e, che con una Medaglia del valore di Zecchini dodici abbia ad esserne gratificato il dotto Professore suddetto. omissis Domenico Calliari Fantinelli sego.’

I take this opportunity of thanking the authorities of the Library for the kind assistance they gave me.

page 292 note 1 The first in his GOR, VIII, 594, the second in Bibliotheca Italiana, LXII, 1831,Google Scholar 308 f.

page 292 note 2 Paris, 1866, published as Extrait du Bulletin de la Société de Géographie (décembre 1865).

page 292 note 3 Jomard, B.F., Introduction à l'atlas des monuments de la géographie, Paris, 1879, 54.Google Scholar

page 292 note 4 Nordenskiöld, A.E., Facsimile atlas, Stockholm, 1889, 89.Google Scholar

page 292 note 5 Fiorini, M., ‘Le projezioni cordiformi nella cartografia’, Boll. R. Soc. Geog. It., Ser. III, II, 1889, 554–78Google Scholar and 676.

page 292 note 6 Gelcich, E., ‘Der tunesische Geograph Hadji Ahmed’, Das Ausland, LXV, 1892, 750.Google Scholar

page 292 note 7 Taeschner, F., ‘Die geographische Literatur der Osmanen’, ZDMG, LXXXVII, 1923, p. 71,Google Scholar n. 3 = joghrāfyā', Turkiyyāt Mejmū‘asi II, 1928, p. 306, n. 4.

page 292 note 8 Bagrow, L., A. Ortelii catalog-its cartographorum. (Erster Teil A-L) (Ergänzungsheft Nr. 199 zu Petermanns Mitteilungen), Gotha, 1928,Google Scholar 67 f., and Die Geschichte der Kartographie, Berlin, 1951, 345.Google Scholar

page 292 note 9 J. H. Kramers, art. ‘Djughrāfiyā’ EI Suppl., 71b.

page 292 note 10 Kenning, J., ‘The history of geographical map projections until 1600’, Imago Mundi, XII, 1955, 12.Google Scholar Keuning is in error in stating that H. A.' map is reproduced as PI. XII of Jomard's, Monuments de la géographie (Paris, 1854);Google Scholar this is a map by Muḥammad b. ‘Alī b. Aḥmad al-Sharfī of Sfax, of A.H. 1009/A.D. 1600–1.

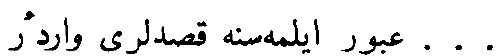

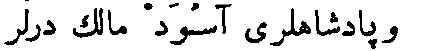

page 293 note 1 Adivar, Adnan, La science chez les Turcs ottomans, Paris, 1939, 70–2,Google Scholar reproduced with slight modifications in ![]() Tūrklerinde ilim, Istanbul, 1943, 73–4.Google Scholar He gives a few lines of the text in French translation in the former and in transcription in the latter.

Tūrklerinde ilim, Istanbul, 1943, 73–4.Google Scholar He gives a few lines of the text in French translation in the former and in transcription in the latter.

page 293 note 2 D'Avezac, p. 65. The last is the copy that had been given to Hammer in 1831 (cf. GOB, VIII, 594). Boni, M. (in Notizia di una casettina geografica …, Venice, 1800,Google Scholar quoted by d'Avezac, p. 20) spoke of a copy in the Museo Naniano, but according to Fiorini (op. cit., p. 570) part of this collection, including the map, had later been dispersed.

page 293 note 3 The Museo Correr had also one of the four sheets making up the map itself, apparently a proof-sheet. Bagrow (Catalogus, 67) records four copies, two in the Marciana and two in Vienna, the latter in the libraries of Metternich and of Hauslab ; but this statement seems to depend on the information given to d'Avezac by Valentinelli, then librarian of the Marciana, which d'Avezac (p. 65, note) corrects: Hauslab' map was not a copy of the 1795 impression of H. A.'s map, but a very similar map by Cimerlinus (see below, p. 298).

As to Assemani' Dichiarazione, it was generally assumed that it too was printed in only 24 copies, one to accompany each copy of the map, but Fiorini shows that there is no justification for thinking that so few were printed. Nevertheless he knew of only four copies, one in the Museo Correr, two in the possession of the Cav. Tessier, and a fourth in the Marciana, the copy which Valentinelli had copied for d'Avezac. On comparing the Marciana copy with the text given by d'Avezac I found that in the latter some misprints have been tacitly corrected ; some mistakes have been made as well, but none that seriously affect the meaning.

page 293 note 4 The Société de Géographie of Paris have kindly permitted me to reproduce the diagram that accompanied d'Avezac' article in their Bulletin. The letters A-F show how the six sheets taken from the blocks had to be assembled : sheets A-D fitted together without adjustment, E was cut in two and the two pieces arranged end to end, F was cut into four strips to form the upper and lower borders.

page 293 note 5 Such ‘cordiform’ projections are described and illustrated in the article by Keuning cited at p. 292, n. 10 above.

page 294 note 1 I and II denote the right- and left-hand columns respectively, arable numerals the lines in each column. Apart from Assemani' rather inaccurate summary of the whole of the companion-text, two lengthy passages from it are known in the translations which Barbier de Meynard made for d'Avezac, deciphering with difficulty—and, understandably, not without mistakes—the small photograph available to him.

page 294 note 2 Text:![]() It was Hammer who first recognized that by ‘Abu'l-Fatḥ’ the author meant the historian and geographer Isma‘ĩl b. ‘All Abu’l-Fidā.

It was Hammer who first recognized that by ‘Abu'l-Fatḥ’ the author meant the historian and geographer Isma‘ĩl b. ‘All Abu’l-Fidā.

page 294 note 3 Text: ![]() Hammer saw that the words

Hammer saw that the words ![]() (rendered by Assemani ‘un opera … intitolata … Delizioso Prato’) meant ‘Book of Mathematics’ and no doubt referred to Abu'l-Fidā' famous Taqwīm al-buldān. The implication of the ambiguous

(rendered by Assemani ‘un opera … intitolata … Delizioso Prato’) meant ‘Book of Mathematics’ and no doubt referred to Abu'l-Fidā' famous Taqwīm al-buldān. The implication of the ambiguous ![]() will be considered below (p. 309, n. 1).

will be considered below (p. 309, n. 1).

page 294 note 4 Text: ![]() There seems to be some confusion here. Perhaps the writer originally intended to say ‘70 years ago’, i.e. in A.H. 897 = A.D. 1491–2, which is indeed the year of Columbus's first voyage. A legend written in the body of the map along the east coast of the Americas says that ‘these lands’ were discovered in 898.

There seems to be some confusion here. Perhaps the writer originally intended to say ‘70 years ago’, i.e. in A.H. 897 = A.D. 1491–2, which is indeed the year of Columbus's first voyage. A legend written in the body of the map along the east coast of the Americas says that ‘these lands’ were discovered in 898.

page 294 note 5 The expression used is generally ![]() (sic, presumably for benzetildi), i.e. this ruler or country ‘has been likened to’ this Planet or House. The belief that a land or city should be under the influence of a certain Planet or House is of great antiquity, but the theory expounded in this text is more elaborate : the author seems to regard geographical entities—lands and cities—as equivalent to constellations and fixed stars, while the political entities—states and rulers—play the part of the Houses of the Zodiac and the Planets; as the states and rulers expand and contract their power they ‘illumine’ different areas of the world just as the Planets (and the Houses ?) ‘illumine’ different constellations in the sky. A system which embraces Temistitan and Peru must be a late (and European) invention; the fact that the Ottoman Sultan is the Sun shows that the arrangement here presented was made expressly for the map. In some cases reasons for the identifications can be guessed: it is natural that Portugal, the great maritime power, should equal Pisces and Turkestan, famous for its archers, Sagittarius; the Leo of Italy may represent the Lion of St. Mark.

(sic, presumably for benzetildi), i.e. this ruler or country ‘has been likened to’ this Planet or House. The belief that a land or city should be under the influence of a certain Planet or House is of great antiquity, but the theory expounded in this text is more elaborate : the author seems to regard geographical entities—lands and cities—as equivalent to constellations and fixed stars, while the political entities—states and rulers—play the part of the Houses of the Zodiac and the Planets; as the states and rulers expand and contract their power they ‘illumine’ different areas of the world just as the Planets (and the Houses ?) ‘illumine’ different constellations in the sky. A system which embraces Temistitan and Peru must be a late (and European) invention; the fact that the Ottoman Sultan is the Sun shows that the arrangement here presented was made expressly for the map. In some cases reasons for the identifications can be guessed: it is natural that Portugal, the great maritime power, should equal Pisces and Turkestan, famous for its archers, Sagittarius; the Leo of Italy may represent the Lion of St. Mark.

page 295 note 1 i.e. the Sudan or ‘Negritia’ of European maps. It is defined as the area bounded to east and west by Abyssinia and the Ocean and to north and south by the Sahara and the land of the Monomotapa.

page 295 note 2 By Temistitan H. A. means New Spain, the province of Mexico. The old Aztec name of the city of Mexico was Tenochtitlán, which appears in various distorted forms in European accounts. H. A.'s spelling seems to derive from that used by Ramusio, who included in the third volume of his Navigationi et viaggi (Venice, 1553)Google Scholar a ‘Relatione d'Alcune Cose della Nuova Spagna, & della gran Città di Temistitan Messicò’.

page 295 note 3 The Monomotapa was the ruler of a negro kingdom in the hinterland of Mozambique (cf. Enc. Brit., eleventh ed., s.v.). This title appears in the map and in the companion-text as a quasi-Moslem patronymic spelt ![]() and

and ![]() and even as the name of a tribe

and even as the name of a tribe ![]() but the position of the name in the map and the description given in the text put the identification beyond doubt. In the first volume of Ramusio'a Viaggi this potentate is called the Benomotapa ; in the map of Africa added to the second edition (1554) his realm is marked as REG. DB BBNOMOTAXA. The latter spelling must lie behind H. A.'s rendering.

but the position of the name in the map and the description given in the text put the identification beyond doubt. In the first volume of Ramusio'a Viaggi this potentate is called the Benomotapa ; in the map of Africa added to the second edition (1554) his realm is marked as REG. DB BBNOMOTAXA. The latter spelling must lie behind H. A.'s rendering.

page 295 note 4 According to H. A. ‘Alaman’ is divided into three parts, the northern part consisting of England, Scotland, Denmark, and Sweden.

page 295 note 5 ‘Sarmatia’ comprises the region from ‘Alaman’ in the west to the Don in the east, the southern boundary being the Danube and the Black Sea.

page 295 note 6 i.e. the Safevid Shah.

page 296 note 1 The whole section was translated by Barbier de Meynard, and parts have been quoted in transcription by Adnan Adivar; nevertheless it is not superfluous to give here the text of the more important passages, not least as a specimen of the language and style. The text is quoted exactly as it is written, with no attempt to emend the numerous errors in spelling and syntax.

page 297 note 1 ![]() does not mean, as Barbier de Meynard understood it : ‘sons la direction d'un professeur’.

does not mean, as Barbier de Meynard understood it : ‘sons la direction d'un professeur’.

page 297 note 2 Firengistān, ‘the land of the Franks’.

page 297 note 3 The passages bracketed thus { | are rendered by Barbier de Meynard (d'Avezac, 44 f., note) : ‘Dans les temps anciens, des savants tels que Platon, Socrate, Aboulfeda, et le grand Locman, philosophes, ont composé dans ces pays des ouvrages ou ils ont dessiné et expliqué la figure du Monde … Moi à mon tour, après avoir vu ces ouvrages rédigés avec perfection …’. But ![]() (in spite of the ḍamma) is to be read qavlinje and

(in spite of the ḍamma) is to be read qavlinje and ![]() stands for

stands for ![]() is to be taken as a singular. H. A. means that this map is (admittedly) the work of the Franks, but it derives from sources acceptable to Moslems.

is to be taken as a singular. H. A. means that this map is (admittedly) the work of the Franks, but it derives from sources acceptable to Moslems.

page 298 note 1 Moreover both were under the impression that Hajji Ahmed had made his map in a Moslem country after being liberated from captivity. Thanks to Barbier de Meynard's translation, d'Avezac demonstrated that the map was made in Europe (in fact in Venice, as will be shown below). D'Avezac also disproved a legend which had grown up in the nineteenth century to the effect that the blocks had been found in a Turkish galley captured by Morosini in 1664; this story is, however, still repeated in the 1913 edition of Baedeker's Northern Italy (p. 365).

page 298 note 2 See above, p. 297, n. 3.

page 298 note 3 Bagrow, Catalogus, 67. One copy is in Nuremberg, one in Paris ; the latter is reproduced as Pl. I in Gallois, L., De Orontio Finaeo Gallico geographo, Paris, 1890.Google Scholar According to Wieder, F.C. (Nederlandsche historiseh-geographische documenten in Spanje, Leiden, 1915, 128)Google Scholar there is in Madrid a copy of Cimerlinus's map dated 1556, i.e. three years before the date of H. A.'s work, but according to Tooley, R.V. (‘Maps in Italian atlases of the sixteenth century’, Imago Mundi, III, 1939, p. 17, No. 19)Google Scholar Almagia has stated that this is an error. Cimerlinus's map is reproduced in the Facsimile atlas, p. 89, and in Bagrow's G. der Kartographie, p. 131.

page 299 note 1 Bagrow (Catalogus, 67 f.) records only one copy, in Nuremberg, but to judge from his description of it a map in private hands, of which the British Museum published a photographic reproduction in 1929 (catalogued ‘Maps 920 [348]’), is a second copy. Mr. R. A. Skelton the superintendent of the Map Room, has been good enough to confirm that this identification is probably correct: he reads the signature on the B.M. photocopy as ‘Jacob[us] Franchus fee. Raph. Faitel(?) form.’. To Mr. Skelton I am also indebted for the identification of ‘Franchus’ as Jacopo Francia ; he adds ‘Another possible identification for Jacobus Franchus is Giacomo Franco (1550–1620), who was active at Venice as an engraver and printseller (also of maps) from 1579, but I find it hard to believe that Finé's map could have been copied after 1580’. The maps of Franchus and Cimerlinus are independent engravings but are practically identical in outline and content.

page 299 note 2 Here are a few examples, with the meaning as revealed by the context:

I, 9 … ![]()

So we begin by saying that …

I, 26 … ![]()

For they mean (intend to convey) that …

I, 85 … ![]()

… apart from the countries of these emperors and the countries subject to the Ottoman House …

I, 117 …

… they intend to cross …

II, 1

Their Emperor is called the Black King (or King of the Blacks ?).

II, 93 … ![]()

… because they are not satisfied with just their native land …

page 300 note 1 The engraver (certainly a European) worked with astonishing care and skill. In one place he must be held responsible for a lacuna : at I, 113, in the description of Peru, several words have been dropped, perhaps one line of the draft from which he was working, and in some words ‘tooth’ is missing.

page 300 note 2 For ![]()

page 301 note 1 The first at I,13 and I,33 (and ma’lūmunuz ola ki at the beginning of the passage quoted on p. 296 above), the second at I, 4 (of. p. 294, n. 3 above), the third at II, 150 (the -siz being written with a typical dīvānī flourish).

page 301 note 2 cf. Wittek, P., ‘Notes sur la Tughra ottomane’, Byzantion, XVIII, 1948,Google Scholar 321 f.

page 301 note 3 II, 142 :![]() ‘No doubt at all remains (that the world is round)’.

‘No doubt at all remains (that the world is round)’.

page 302 note 1 The first at I,109 : ‘In these lands there are few ![]() most of the people living in villages’

most of the people living in villages’

The word ![]() appears twice in the text (I, 104 and I, 109) among the products of the

appears twice in the text (I, 104 and I, 109) among the products of the ![]() and of the Land of the Blacks. Assemani translated ‘carne’ (d'Avezac, p. 34), apparently reading the word as T kavurma; this is unconvincing : the word stands first in each list, and it would be strange if the products of the

and of the Land of the Blacks. Assemani translated ‘carne’ (d'Avezac, p. 34), apparently reading the word as T kavurma; this is unconvincing : the word stands first in each list, and it would be strange if the products of the ![]() did not include dates.

did not include dates.

page 302 note 2 This hypothesis may also explain the strange rendering of ‘Lokman’ in 1. 10 of the passage quoted on p. 296 above. One is tempted to emend the impossible ![]() of the text to

of the text to ![]() That a copyist's eye should jump the word

That a copyist's eye should jump the word ![]() in Arabic script unlikely, but in Latin script it could easily happen with some spelling such as ‘muazzam alhucama Lucmã’. However, it is so strange to find this pre-Islamic sage cited as an authority that it may be that the writer intended somebody quite different.

in Arabic script unlikely, but in Latin script it could easily happen with some spelling such as ‘muazzam alhucama Lucmã’. However, it is so strange to find this pre-Islamic sage cited as an authority that it may be that the writer intended somebody quite different.

page 302 note 3 The name of Jesus, appears three times, as ![]() and

and ![]() Does this last strange spelling reflect an Italian ’Gesù’ ? ‘Christian’, rendered three times correctly by

Does this last strange spelling reflect an Italian ’Gesù’ ? ‘Christian’, rendered three times correctly by ![]() appears three times also as

appears three times also as ![]() instead of the normal spelling

instead of the normal spelling ![]() Another odd feature is that dates (expressed three times in different locutions employing the word

Another odd feature is that dates (expressed three times in different locutions employing the word ![]() appear three times as

appear three times as ![]() surely an unnatural expression for a Moslem to use.

surely an unnatural expression for a Moslem to use.

page 303 note 1 Reproduced at p. 136 of Bagrow's G. der Kartographie.

page 303 note 2 St. Kilda, a tiny island lying to the west of the Outer Hebrides, is shown by Lily, with the name Hirtha, as a large island situated north of Scotland, which is where H. A. shows ![]() The inclusion by H. A. of this remote islet suggests that he was influenced, directly or indirectly, by Lily's map, which marks it with such undue prominence and in the same position.

The inclusion by H. A. of this remote islet suggests that he was influenced, directly or indirectly, by Lily's map, which marks it with such undue prominence and in the same position.

page 303 note 3 As Assemani pointed out, with examples. D'Avezac comments very little on the placenames, as they were mostly illegible on bis small photograph of the map.

page 303 note 4 But ![]() in the companion-text.

in the companion-text.

page 304 note 1 Sofala in Portuguese East Africa (in the Arab geographers, including Abu'1-Fidā, ![]() appears as

appears as ![]() ; the Portuguese spelling Çofala or its Italian rendering Cefala may be responsible for H. A.'s kāf.

; the Portuguese spelling Çofala or its Italian rendering Cefala may be responsible for H. A.'s kāf.

page 304 note 2 cf. also ‘Fez’ and ‘Morocco’ in the companion-text (p. 301 above).

page 304 note 3 Such influence in the description of countries outside the Moslem world is of course only to be expected : thus there are clear echoes of the accounts of European travellers in the statements that the inhabitants of Patagonia are giants, that the people of Brazil wear feathers, that the Niger probably rises in the same region as the Nile, that the people of Bengal worship cows and snakes, etc.

page 305 note 1 The writer must mean ![]()

page 305 note 2 The last word is perhaps ‘Sarmatia’.

page 305 note 3 Vol. II of the Viaggi was the last of the three volumes to appear. The preface is dated July 1553, but publication was delayed by a fire in the Giunti printing-works, so that the titlepage of the first edition bears the date 1559 (two years after Ramusio's death). However, as the last page bears the date 1558 and the compiler of the map was working after October 1559 (when the Hijra year 967 began) there is no doubt that this volume was available to him.

page 306 note 1 The new French translation of Leo, (Description de l'Afrique, tr. Epaulard, A., Paris, 1956),Google Scholar which has been made from early MSS of the Italian text, reads here ‘24’, a very reasonable date. The ‘400’ in Ramusio' text is clearly a slip: either the copyist of the MS which Ramusio used or the compositor of the printed text has been influenced by the ‘400’ appearing a few lines further on.

page 306 note 2 Other items of Moslem history mentioned in the text (for which I cannot suggest the source) are :

I, 52 if. ‘In the year 580 of the Hijra [Africa] was ruled over by a mighty Moslem emperor who lived in the city of Morocco and conquered Syria, Arabia, Egypt, all Africa, Spain and Sicily.’

I, 127 f. ‘In the year 337 of the Hijra the Caliph of Baghdad and the Caliph of Egypt fell into enmity with each other, and the Caliph of Baghdad called in [the Turks] to assist him …’

I, 134 ff. ‘About 800 years ago some of the tribesfolk left Arabia … massed together in a great army … and conquered Syria and Egypt …’

II, 65 ff. ‘In the year 125 of the Hijra a Moslem prince from the ![]() named

named  conquered Spain.’

conquered Spain.’

page 307 note 1 A ‘ruttier’ or ‘rutter’ was a manual of sailing directions for a particular coast (cf. for example ‘A ruttier for Brazil’ in Hakluyt' Voyages, XI). From the ruttiers geographical handbooks were compiled: a famous sixteenth century example was the Spanish Suma de geographia of 1519 by Enciso, which was translated, with modifications, into English by Roger Barlow in about 1541. Barlow's MS has been published by the Hakluyt Society (A brief summe of geographie, ed. Taylor, E.G.R., 1931Google Scholar [Ser. II, LXIX]). It contains very similar information to that given by H. A. and the descriptions of the countries are on the same pattern—limits, characteristics, products. Such a book probably served as a model for the compiler of the text and could have provided a mass of detail to add to an already existing map.

page 307 note 2 And rightly : Abu'l-Fidā' Taqwīm begins with a number of astronomical proofs that the earth is spherical.

page 308 note 1 In making him a graduate of Fez the compiler was perhaps influenced by the fact that Leo Africanus had studied there.

page 308 note 2 Valentinelli, the librarian of the Marciana, informed d'Avezac of the existence of these records, which had been discovered by his assistant Lorenzi. His communication (quoted by d'Avezac, p. 64) suggests that the documents were actually in Lorenzi's possession, but Barozzi (in the course of a notice of d'Avezac's article in Raccolta Veneta, I, 2, 1866,Google Scholar 130 f.) makes it clear that Lorenzi had transcribed documents preserved in the State Archives at the Frari.

page 308 note 3 The Riformatori dello Studio were a board of three patricians set up by Venice in 1517 as supervisors of the University of Padua. To this board the Council of Ten had in 1544 entrusted the censoring of all works submitted for publication. (The text of the decree is given in the little pamphlet Porte dell' illustrissima signoria di Venetia in materia delle stampe, Venice, 1565, of which there is a copy in the British Museum.)

page 308 note 4 The word ‘ osservate’ does not appear in the Italian text as quoted by d'Avezac, but as he translated ‘observées par’ and the word appears in the second text I assume that it has been accidentally omitted.

page 308 note 5 On a visit to the Frari I found the grant of the monopoly recorded in Vol. 47 (1568–9) of the series ‘Senato Terra’. The entry begins (f. 31r) : ‘Di xiii Detto (sc. Maggio 1568) :

Che al diletto nobil nostro Marc’ Antonio Giustignan sia concesso, sicome egli hà humilmente supplicate, che altro, che esso, ò chi haverà da lui causa, ò licentia, non possa in questa, ne in altra città, ö luogo del Dominio nostro stampar, far stampar, ne da altri stampato vender il Mapamondo in Arabo con le graduationi …’ etc. Then follow a provision that every infringement of the monopoly was to be punished by a fine of 300 ducats, the statement how the fine was to be spent, and the record of the voting, with a note that G.'s relatives abstained. That the description of the map given in this minute is that supplied by G. himself in his application is shown by comparison with the application of Antonio Pigafetta of 5 August 1524 (reproduced as Pl. 16 in the catalogue Navigatori Veneti del quattrocento e del cinquecento, Venice, 1957Google Scholar), which includes not only a description of the work in question but also a proposal for the amount of the fine and how it should be apportioned.

In the short time at my disposal I could not trace the two other references. The bundle Riformatori dello Studio di Padova 284 contains original applications to the censors (each accompanied by the nihil obstat granted) for the years 1550–78, but I could not find G.'s application among them.

page 309 note 1 The Italian wording can hardly imply that the map was drawn up ‘according to the data’ of Abu'l-Fidā's observations, though this seems to be the force of ![]() in the companion-text (see above, p. 294, n. 3), evidently meant to impress the Moslem reader. If such an implication was intended, either in the Italian or the Turkish, it has no justification. Figures of latitude and longitude given in the companion-text for the extreme limits of countries agree with the representation (after Orontius) of the countries in the map. As for the towns marked in the map, a few examples of the positions of Moslem towns show that the compilers did not, as they might well have done, rely on Abu'1-Fidā: whereas for the latitude of Tiflis Abu'1-Fidā reports two figures, 43° and 42°, for Hasankeyf 37° 35́, for Kayseri 40°, for Mosul 33° 35́, for Samarcand 40° and 37° 30́, for Vostan 37° 50́, and for Sultania 39°, H. A.'s map shows

in the companion-text (see above, p. 294, n. 3), evidently meant to impress the Moslem reader. If such an implication was intended, either in the Italian or the Turkish, it has no justification. Figures of latitude and longitude given in the companion-text for the extreme limits of countries agree with the representation (after Orontius) of the countries in the map. As for the towns marked in the map, a few examples of the positions of Moslem towns show that the compilers did not, as they might well have done, rely on Abu'1-Fidā: whereas for the latitude of Tiflis Abu'1-Fidā reports two figures, 43° and 42°, for Hasankeyf 37° 35́, for Kayseri 40°, for Mosul 33° 35́, for Samarcand 40° and 37° 30́, for Vostan 37° 50́, and for Sultania 39°, H. A.'s map shows ![]() in 45°,

in 45°, ![]() in 39°,

in 39°, ![]() in 41°,

in 41°, ![]() in 36°,

in 36°, ![]() in 48+,

in 48+, ![]() in 40°, and

in 40°, and ![]() in 40°. In no case do the figures of A. F. and H. A. agree—and in all cases except one (Mosul) A. F.' are more accurate.

in 40°. In no case do the figures of A. F. and H. A. agree—and in all cases except one (Mosul) A. F.' are more accurate.

page 309 note 2 D'Avezac' interpretation is that H. A. drew up the whole work in Arabic, and that ‘ses legendes arabes avaient été mises en turk à tout le moins avec l'aide de Membrè et Cambi’. Adnan Adivar (La science, p. 72) rejects this explanation because of H. A.' positive statement that he wrote the Turkish text himself; he suggests that H. A. dictated the text in bad Turkish, and that the ‘translation’ was made into Italian, in connexion with the application for permission to publish.

page 310 note 1 Slight though this acquaintance must have been, since A. F.' Taqwīm al-buldān is referred to not by its title but only as the ‘Book of Mathematics’, statements on the importance of geography attributed to him are not to be found in the text of the Taqwīm, and even the name Abu'l-Fidā, is mis-spelt as Abu'1-Fatḥ.

page 310 note 2 Viaggi, II, Preface, f. 18. With very few exceptions the figures given by Ramusio agree with those in the printed text of the Taqwīm (ed. Reinaud and de Slane, Paris, 1840), except that in all cases where Abu'1-Fidā gives a figure as an exact number of degrees Ramusio adds 8 minutes, e.g. for A. F.'s ‘Tiflis: Long. 73°, Lat. 43°’, R. has ‘Tiphlis: Long. 73° 8̐, Lat. 43° 8̐’ it seems that R.'s translator had read ![]() as the numeral Λ.

as the numeral Λ.

page 310 note 3 Viaggi, II, Preface, f. 14v. Among the Persians Ramusio interrogated with Mambre's help was a merchant named ‘Chaggi Memet’. V. Lazari, in his I viaggi di Marco Polo …, Venice, 1847 (quoted by d'Avezac, p. 59), suggested that this Hajji Mehmet was the author of the map. Dd'Avezac pointed out that this identification was impossible, but it may be the reason why the map is sometimes referred to in modern guide-books as the work of‘Haji Mohammad’.

page 311 note 1 cf. Roth, C., Venice, in the ‘Jewish Communities Series’, Philadelphia, 1930, 254 ff.Google Scholar

page 311 note 2 Bombaci, A., ‘La collezione di documenti turchi dell' Archivio di Stato di Venezia’, Bivista degli Studi Orientali, xxiv, 1949, 95–107Google Scholar. The phrase quoted appears in Bombaci' article in RO referred to in the next note.

page 311 note 3 See Bombaci, A., ‘Una lettera turca in caratteri latini del dragomanno ottomano Ibrāhīm al veneziano Michele Membre (1567)’, Rocznik Oryentalistyczny, xv, 1949, 129–44.Google Scholar A similar flavour of chancery style to that noticed in the companion-text is to be detected in Ibrahim' letter: he too begins with ‘malu(m) olla kym’ (262r 1) and concludes the first part of his letter with ‘sǔile bilesis’ (262v 20); he also includes a ‘ssymdi ky chalde’ (262r 17) and an admonitory ‘tallul ittermeyp’ (262v 28). Ibrāhīm often renders initial Turkish i- by y- (ylcenn, ydesis, etc.); this rendering may lie behind such spellings as ![]() = Istanbul and

= Istanbul and ![]() =

= ![]() in H. A.' map.

in H. A.' map.

page 312 note 1 On Ibrāhīm and his transcription of a letter of Suleyman I see Zajączkowski, A., ‘List turecki Sulejmana I do Zygmunta Augusta’, RO, ii, 1936, 91–118Google Scholar; on Murād see Babinger, F., ‘Der Pfortendolmetsch Murād und seine Schriften’ in Literaturdenkmäler aus Ungarns Türkenzeit ed. by Mittwoch, E. and Mordtmann, J.H.), Berlin and Leipzig, 1927, 33–54.Google Scholar

page 312 note 2 The memory of Giustinian's earlier venture of the Hebrew press may have contributed to his being regarded with suspicion, since it was generally believed that the Sultan' hostile attitude was due to the urging of his powerful Jewish protégé, Joseph Nasi.

page 313 note 1 cf. Nüzhet, Selim, Türk ![]() , Istanbul, 1928, p. 11Google Scholar and appendix, where the firman is reproduced; also Duda, H.W., ‘Das Druckwesen in der Tttrkei’, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, 1935, 228 f.Google Scholar

, Istanbul, 1928, p. 11Google Scholar and appendix, where the firman is reproduced; also Duda, H.W., ‘Das Druckwesen in der Tttrkei’, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, 1935, 228 f.Google Scholar

page 313 note 2 Of the four parts of the book only the third, the History of the Mongols, is given by Ramusio. As he states in his preface (f. 61r), he used a manuscript ‘over 150 years old’, which was, according to the editors of the critical edition, a text in the Latin version.

- 4

- Cited by