Article contents

The Gadabuursi Somali Script

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

Extract

At the moment, both in the British Protectorate and in Somalia, the adoption of a standard orthography for the Somali language is fiercely debated. In discussion of the merits of the various scripts proposed, technical problems of orthography have to some extent been lost sight of. Nationalistic arguments have favoured ‘Somali writing’ (‘Ismaaniya) while religious or Pan-Islamic arguments have supported an Arabic script. This article discusses an orthography invented some 20 years ago by a well-known Gadabuursi sheikh, Sheikh ‘Abduramaan Sh. Nuur, the present Government Qā1E0D;ī of Borama District in the west of the British Protectorate. The script has not, as far as I am aware, been previously described in the literature on Somaliland. I publish it here with no intention of attempting to contribute to the already abundant confusion in the choice of a standard orthography for Somali.

- Type

- Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 1958

References

page 134 note 1 The dispute over the adoption of an orthography may be studied from the numerous articles on the subject which have appeared over the past few years in British Somaliland in the periodical War Somali Sidihi, and in Somalia in I1 Corriere della Somalia and more recently in Somalia d'Oggi. A brave, if unwise, attempt to solve the problem was made in March 1957 by the Government of Somalia which launched Wargeyska Somaliyed, a newspaper printed entirely in a phonetically accurate but simple transcription of Somali in roman characters. The publication of this journal, using roman characters as a medium for Somali, raised such a storm of popular protest— especially from the advocates of ‘Ismaaniya—that it had to be withdrawn from publication after a few numbers had appeared.

page 134 note 2 I spent a little under two years, during 1955–7, mainly in the British Protectorate, as Fellow in Social Anthropology of the Colonial Social Science Research Council, London, to whose generosity I am greatly indebted for financing my research.

page 134 note 3 Place-names in this article are normally spelt according to general Administrative usage in the Protectorate. In writing other Somali words Andrzejewski's transcription as used in Bell, 1953, and Andrzejewski and Galaal, 1956, is followed. Proper names of persons although of Arabic origin in many cases are represented in this orthography with their Somali pronunciation. The Somali pronunciation of other Arabic expressions used is also indicated.

page 134 note 4 The expression ‘Somaliland’ is used here to denote all the Somali countries, and not simply the British Protectorate.

page 134 note 5 Several attempts appear to have been made by Somalis, with in many cases European encouragement—governmental or missionary—to write Somali in roman characters. Such scripts—other than the conventional systems used by officials for writing personal and placenames in roman characters—have acquired little or no general currency. Adaptations of roman characters to represent Somali sounds are, of course, not inventions in the sense that the Gadabuursi and 'Ismaaniya scripts are.

page 135 note 1 The Sharif's tomb which is the scene of an annual pilgrimage (siyaaro-da) mainly for the clans of the Ishaaq clan-family is situated some 20 miles to the north-east of Hargeisa. See Webber, 1956. For an indication of the Sharif's role in Somali tradition, see Lewis, 1956, 153. I hope to discuss the Sharif more fully elsewhere.

page 135 note 2 Lit. ‘alif (which) is surmounted’.

page 135 note 3 Lit. ‘ alif (which) is undercut’.

page 135 note 4 Lit. ‘alif (which) is hollowed-out’.

page 135 note 5 Wadaad is a Somali synonym for the Ar. sheikh, but in Somaliland the word sheikh often denotes a slightly higher status in religion than does wadaad.

page 135 note 6 Literally, ‘begging, or beseeching, God’. Other expressions are also used, as e.g. Allaahbari, and in Hawiye dialect the probably pre-Islamic compounds Waaq da'il and Waaq da'in, from Waaq, one of the pre-Islamic Cushitic names of God.

page 136 note 1 The most commonly studied religious works are standard authorities on the ![]() . mainly of the Shyāfi‘ite school to which the majority of Somali adhere, with, of course, the Qur’ān and various compilations of ḥadīths. The Ṣūfi Dervish Orders (Qaadiriya, Ahmadiya-Rahmaaniya, Ahmadiya-Saalihiya, and Ahmadiya-Dandaraawiya, to name the principal ṭarāqas) provide in their literature, hagiologies (manaaqibs), poetry (qasiidas), etc., a rich source of reading material for the student of religion. Outside the ṭarīqas, strictly, but associated with them are the hagiologies and poems composed in honour of Somali clan and lineage ancestors, transmuted in Somali Islam into Ṣūufīsaints. For Somali Sufism see Cerulli, 1923, and Lewis, 1956. It is hoped shortly to publish a more up-to-date appraisal of Sufism in Somaliland.

. mainly of the Shyāfi‘ite school to which the majority of Somali adhere, with, of course, the Qur’ān and various compilations of ḥadīths. The Ṣūfi Dervish Orders (Qaadiriya, Ahmadiya-Rahmaaniya, Ahmadiya-Saalihiya, and Ahmadiya-Dandaraawiya, to name the principal ṭarāqas) provide in their literature, hagiologies (manaaqibs), poetry (qasiidas), etc., a rich source of reading material for the student of religion. Outside the ṭarīqas, strictly, but associated with them are the hagiologies and poems composed in honour of Somali clan and lineage ancestors, transmuted in Somali Islam into Ṣūufīsaints. For Somali Sufism see Cerulli, 1923, and Lewis, 1956. It is hoped shortly to publish a more up-to-date appraisal of Sufism in Somaliland.

page 136 note 2 Men are traditionally divided by profession into those who are warriors (waranleh) and those who devote their lives primarily, whatever subsidiary occupation they may pursue, to religion (toadaad).

page 136 note 3 Text I, below, p. 144, is a good example of a Somali qasiida.

page 136 note 4 Few works by Somali writers have been published but there are many original manuscripts, some of which one hopes may some day be printed in Mogadishu. Sayyid Mahammad ˛Abdilleh Hassan (b. 1864, d. 1920, the celebrated ‘Mad Mullah’), for example, has left a considerable number of MSS. Some of the better known published works are the majmū˛at al-mubāraka of Sh. ˛Abdallah ibn Yuusuf al-Qalanqooli (of the Qaadiriya), Cairo, 1918–19 (see Cerulli, 1923, 22–5); the majmū˛at al-qasā˛id collected by the same author, Cairo, 1949, very popular amongst members of the Qaadariya Order in Somaliland; and Sh. ˛Abdurahmaan az-Zeila˛i's Arabic grammar, fatb al-latīf, Cairo, 1938. An interesting secular work is mentioned below.

page 136 note 5 This group comprises, of course, the majority of the population since everyone knows the Muslim prayers in Arabic (the daily prayers) and a few Arabic words.

page 136 note 6 Broken English is also frequently used in petition writing. Both it and obscure wadaad's writing have the great merit, where the writer wishes (and no doubt frequently involuntarily) of enabling the petition to be couched in legal ambiguity so that the meaning of finer points of detail is seldom clear. This provides the writer with talking points should dispute arise concerning the meaning of the petition.

page 137 note 1 The glottal stop.

page 137 note 2 The Arabic ![]() .

.

page 137 note 3 The voiced post-alveolar plosive.

page 137 note 4 The voiced dental plosive, corresponding to the Arabic د. Moreno, 1955, 8, includes also d Somalization of the Arabic ذ. But this sound seems very rare in northern Somali.

page 137 note 5 Correctly the Arabic ![]() .

.

page 137 note 6 Andrzejewski introduces an additional consonant ![]() , which he describes as ‘acoustically similar to y but less tense and darker’, Andrzejewski and Galaal, 1956, 2.

, which he describes as ‘acoustically similar to y but less tense and darker’, Andrzejewski and Galaal, 1956, 2.

page 137 note 7 The q is sometimes in eastern Somaliland pronounced as the Arabic غ.

page 137 note 8 There are slight dialectal differences in the speech of the ˛Iise clan in the west, the central Ishaaq, and the Daarood in the east, and again between the Daarood and the Hawiye (all of whom are collectively ‘Samaale’, see Lewis, 1955, 15) but these are slight compared with the differences between these as a whole and the Banaadir and Rahanweyn dialects of southern Somalia; cf. Andrzejewski and Galaal, loc. cit., 1. See also Moreno, loc. cit., passim.

page 137 note 9 Both Armstrong, 1934, and Andrzejewski, 1955, 568, distinguish two values for each of the ten vowels according as the vowel is articulated with or without ‘fronting’.

page 137 note 10 The original, written in pencil, could not be reproduced and the block has accordingly been made from a carefully traced copy.

page 138 note 1 ˛Ainabo, a small town in the east of the Protectorate.

page 138note 2 Bura˛o, a large town in the east of the Protectorate.

page 138 note 3 Habar Ja˛lo, a large Ishaaq clan in the east and centre of the Protectorate.

page 138 note 4 Somali fariira-ta ‘message’.

page 138 note 5 English ‘rations’, Somalized to raashin-ka.

page 138 note 6 Somali reer-ka ‘nomadic family, household, family, people’.

page 138 note 7 Somali ‘aas-ka ‘family’.

page 139 note 1 For the Tunni of southern Somalia, see Lewis, 1955, 32 and passim. For further information concerning the Sheikh see the majmū˛at al-mūbāraka mentioned above and Cerulli, 1923, 12, 22.

page 139 note 2 In northern Somaliland, on the other hand, most of the Qaadiriya follow the teaching of Sh. ˛Abdurahmaan az-Zeila˛i.

page 139 note 3 For the Digil see Lewis, 1955, 31 ff., and for their dialect, Moreno, 1955, 327 ff.

page 139 note 4 See Lewis, op. cit., 42 ff.

page 139 note 5 Moreno, loc. cit., 364–7.

page 139 note 6 Of the Ishaaq, Habar Awal clan.

page 139 note 7 Published in Bombay, A.H. 1345, as ![]() .

.

page 139 note 8 Galaal, 1954. In his original article, Muuse Galaal used ج to represent Somali j, but has since decided, more logically, to use this letter for Somali g.

page 140 note 1 For the Somali Daarood clan-family, see Lewis, 1955, 18 ff.

page 140 note 2 Cerulli, E., ‘Tentativo indigeno di formare un alfabeto somalo’, Oriente Moderno, XII, 4, 1932, 212–13Google Scholar.

page 140 note 3 Maino, 1951,1953.

page 140 note 4 Some emphasis has been given to ˛Ismaaniya, regarded as a national Somali script by the Somali Youth League political party. The script is sometimes used, symbolically, as much as practically, in S.Y.L. proceedings in the Protectorate.

page 140 note 5 See Maino, 1953, 26 ff., and Moreno, 1955, 290 ff.

page 140 note 6 For alphabet see n. 3 on next page.

page 140 note 7 ‘ cf. Maino, loc. cit., 26 ff.

page 140 note 8 See Bell, 1953, 7 ff.

page 141 note 1 SeeBelUoc.eit.,12.

page 141 note 2 See Bell, loc. cit., 8.

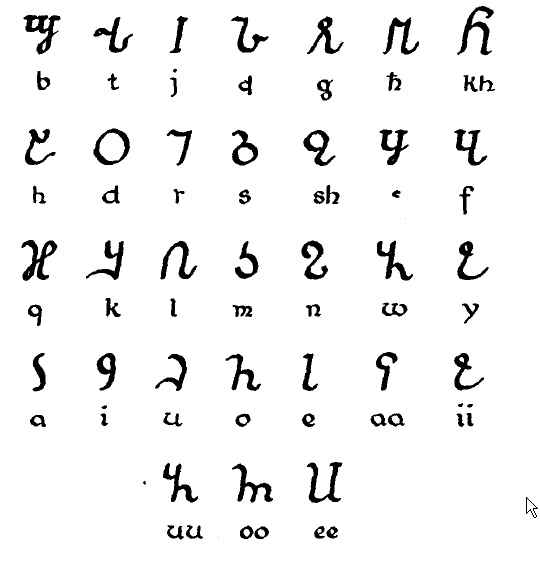

page 141 note 3 The alphabet is:

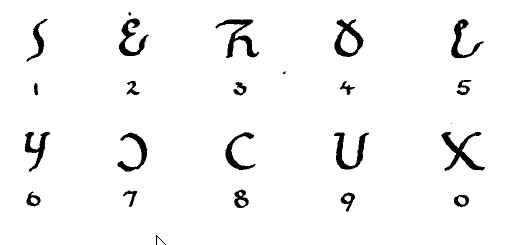

The numerals are:

page 142 note 1 See the examples below.

page 142 note 2 The Gadabuursi clan inhabit the west of the British Protectorate and the northern part of the Harar province of Ethiopia. See Lewis, 1955, 25.

page 142 note 3 He has written in Arabic some MSS on Gadabuursi history.

page 142 note 4 My attention was first drawn to the script by my friend Mr. J. Gethin, H.M. Consul, Mogadishu. I studied the script with its inventor, Sh. ˛Abdurahmaan, while on a visit to the Gadabuursi of Borama District.

page 143 note 1 For the problem of tone in Somali, see Andrzejewski, 1956.

page 143 note 2 Mr. Muuse Galaal and Mr. Yuusuf Maygaag have very kindly advised me in the writing of this article and in the transcription and translation of the texts. I wish to thank also Mr. P. J. Raine of the Education Department, British Somaliland, for his expert help in the preparation of scripts and texts for the printers.

page 145 note 1 In these translations I have tried to adhere as closely as possible to the literal meaning within the requirements of reasonably intelligible English. This is probably most difficult in a qasiida although it is difficult also in Somali secular poetry because of the use of imagery and metaphor. This qasiida was written by Sh. Isma˛iil Farah (d. c. 1910) of the Habar Awal clan (Reer Ahmad). For the Habar Awal clan, see Lewis, 1955, 23 ff. The qasiida is well-known in the Protectorate.

page 145 note 2 When the Prophet went with a caravan he caused clouds to shade its journey.

page 145 note 3 Qoyaan, lit.‘wet’ as opposed to qori ‘dry, dead wood’. The phrase refers to the miraculous life-giving power of the Prophet.

page 145 note 4 This sentence means simply that through his miraculous power, the Prophet would be aware of the presence of someone standing behind him.

page 145 note 5 This sentence refers to ḥadīths describing the Prophet's demeanour when he smiled which has set a style of propriety in expressing pleasure or mirth. This religious tradition is probably associated with the common Somali idea that a man who opens his mouth wide when he smiles or laughs is not to be trusted.

The following words have the Arabic correspondences shown: nebi Ar. n-b-y; salaat Ar. s-l-˛-t; salaam Ar. s-I-˛-m; ˛ahyka Ar. ˛-l-y-k; qasiida Ar. q-s-y-d-t; Rabbi Ar. r-b; qiyaasi Ar. q-y-˛-s; qaafilo Ar. q-˛-f-I-t; qamaam Ar. g-m-˛-m; qawl (in the compound qawlun) Ar. q-w-1; qalbigii Ar. q-l-b.

page 147 note 1 The ancient but now deserted town, at various times capital of the Muslim state of Awdal (ninth/tenth-sixteenth centuries), on the north-west coast of the British Protectorate. Wellknown place-names are here spelt as in common administrative usage in the Protectorate.

page 147 note 2 Lit. ‘it is peace’, meaning above all spiritual equilibrium, not simply the absence of war. A rather perfunctory greeting, as here, the writer would be somewhat disturbed by the loss of the camel.

page 147 note 3 Here, the nomadic hamlet, comprising a man's hut, sheep and goats, and possibly some milch camels and cattle, with his wife and children (by her) and probably a few families of close kin with their huts and stock. Each wife normally has one hut. The word reer is also used in other more general senses, as e.g. to mean ‘people’, but this is its basic meaning. For a general introduction to the structure of nomadic Somali society see my The Somali lineage system and the total genealogy (duplicated), Hargeisa, Somaliland Protectorate, 1957.

page 147 note 4 A village in the west of the. Protectorate.

page 147 note 5 The article -kaa indicates that the person spoken of is more directly related to the recipient of the letter than to the sender. This possibly refers to the recipient and sender being of different mothers (Som. kala hooyo).

page 147 note 6 The capital of the British Protectorate, of recent foundation and with no traditions of any considerable antiquity.

page 147 note 7 The administrative centre of Borama District in the west of the Protectorate, home of Sh. ˛Abdurahmaan author of our script.

page 149 note 1 Lit. ‘What Ugaas Nuur said’. Ugaas Nuur Ugaas Roobleh, Sultan (Ugaas) of the Gadabuursi clan, is said to have died about 1898.

page 149 note 2 Eebbe is an ancient and still-used Somali name for God.

page 149 note 3 This rhetorical eontinuative emphasized in the arrangement of the words is continued throughout the gabay. For information on Somali folk-literature and poetry see Kirk, 1905, 170 ff., Maino, 1953, 44 ff., and Laurence, 1954, 5 ff.

page 149 note 4 Lit. ‘in the matter’.

page 149 note 5 Lit. ‘yielded patiently to people (rag)’.

page 149 note 6 Metaphor for any kind, or sweet, action as rendered here by the speaker to his enemy.

page 149 note 7 The speaker sows a scheme of treachery to catch his enemy. From his brooding will come the seeds of the plan which will secure his enemy's downfall. Daadi ‘to scatter’ is used of feeding grain to poultry.

page 149 note 8 A trap for wild animals and game.

page 149 note 9 Degd-ka usually means an old camp-site, deserted, but sometimes returned to; here it has the less common meaning of chest associated with the idea of bringing near. The whole theme of the poem is that the speaker bides his time waiting only until the time is ripe to strike his enemy. The proud nomad does not forget an insult although he may appear to do so.

page 149 note 10 The construction here is involved. The speaker gave his enemy dayaan (lit. ‘the crashing sound of a blow’) with some unstated object implied in the use of kaga. The first three words mean ‘without him taking warning’.

page 152 note 1 In this poem the poet praises his horse. Very many geeraar have such a theme.

page 152 note 2 A small town, formerly more important and prosperous than it is to-day, to the west of Berbera in the Protectorate.

page 152 note 3 A mountain in the west of the Protectorate.

page 152 note 4 The gob (Zizyphous mauritiana) is one of the largest and most noble of the common trees in the Protectorate. Its fruit is relished by man and beast and its shade is much sought after.

page 152 note 5 A place in the Gadabuursi country to the west of the Protectorate.

page 152 note 6 Gudgude-ha is a swiftly moving night rain-clond. The word is related to gud ‘to travel by night’.

page 152 note 7 Gole-ha ‘a place where men (and certainly formerly horses) gather ’; a meeting-place.

page 152 note 8 Aar-ka ‘the male lion’, gool-sha ‘the lioness’.

page 152 note 9 Gabangoobi-da ‘a flat area or plain’, here deserted, and the retreat of the raiders whose presence is implied. Lit. ‘he kneels (tui) the camels’. The horse is here praised for its part in stock-looting. Its prowess and stamina enable the rider to capture many camels and bring them back to camp to unload.

page 152 note 10 Gob means ‘noble, of aristocratic birth or lineage’, as opposed to gun (lit. ‘the bottom’) meaning of common, undistinguished, birth. The word gob is applied to anyone, with the general exception of the despised leather-workers, smiths, etc. (the Midgaans, Turaaals, Yibirs, etc.) whose actions conform to the Somali conception of noble conduct. Reer means here ‘nomadic hamlet’, as in Text II, p. 147, n. 3, above.

page 152 note 11 Hal ‘one (of anything)’, here denotes a single strand of hair.

page 152 note 12 Galool the acacia tree, Acacia bussei, bursts into a cascade of light feathery yellow flowers at the beginning of spring with the coming of the rains. The image here is not only of the colour of the flower but contains also the implication that its blooming heralds the long-awaited spring rains. The galool also flowers again later in the year.

page 153 note 1 This fragment comes from a well-known gabay by Ugaas Nuur, see Text III, p. 149, n. 1.

page 153 note 2 The Somali divide the feathered vertebrates into two main classes. Birds of prey are known collectively as had-ka. Other (non-carnivorous) birds are called shimbir-ta usually translated in English as ‘bird’. This is only partly correct as birds of prey are not shimbir. The ostrich belongs to neither class and is not considered as a bird. It is grouped with all game animals (ugaaɖ-da) and is hunted, less frequently now than formerly, for its excellent fat used for making ghee. The antithesis is here between the great ostrich which shows less ingenuity in the care its young than any small nesting bird.

page 153 note 3 Aroos-ka is the house built for the bridal couple by the parents of the girl in return for the bride-price (yarad-ka) paid by the husband and his kin. It also means bridegroom, or marriage. The aroos is in fact the newly constructed, abundantly equipped, especially adorned, house, built for the bride and her husband before the wedding and which they will probably occupy for the rest of their lives. In the interior it is the collapsible mat and skin-covered hut (aqal), built on a frame of boughs lashed together, of the nomads.

page 153 note 4 ˛aqlays from the Ar. ˛-q-l plus contracted is. Awr, literally ‘male burden camel’, is used metaphorically here as a unit of large size. This is quite a common metaphorical use. These three lines have assumed almost the currency of a proverb to the effect that bulk and brawn are not the same as ingenuity.

page 155 note 1 Waraaqdan, cf. Ar. w-r-q-t.

page 155 note 2 cf. Ar. m-˛-w-z.

page 155 note 3 cf. Ar. k-w-f-y-t.

page 155 note 4 Garbagale-ha ‘shirt’, from gal ‘to enter’ and garbo ‘shoulders’, the garment the shoulders enter.

page 155 note 5 For the meaning of the word reer see Text II, p. 147, n. 3.

page 155 note 6 The sorghum (haaɖuuɖ-ka) is grown in the Protectorate only in significant quantities in Hargeisa and Borama, Districts in the west of the country, and is harvested between September and December according to the year. There is generally only one main crop each year. Much of the crop is brought into the markets of towns like Hargeisa by trade truck and sold if a good price is offered very shortly after it has been cut and thrashed in the fields. The money thus obtained provides ready cash for the purchase of necessities such as clothes and cooking utensils. At this time of year, unless the harvest has been disastrous, people are normally contented and happy, and during and immediately after the harvest the marriage season of the cultivators in the west of the Protectorate is in full swing.

page 155 note 7 Sahan dambe ‘the day after to-morrow’ is Gadabuursi dialect. In the centre and east of the Protectorate the expression is saa dambe.

- 4

- Cited by