Introduction

Diminutive personal names, tribal names, place names and plant terms are ubiquitous in most areas of the Arabian Peninsula. This study seeks first to elucidate some of the semantic and pragmatic peculiarities of morphologically diminutive names and, secondly, to investigate their geographical distribution and relative frequency across dialects. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of an extensive onomastic and lexical database indicates that the diminutive pattern CiCēC (cf. Classical CuCayC) has meanings and functions in Arabic onomastics that are distinct from its meanings and functions in common nouns. This extension of use also pertains to terms for flora and certain kinds of fauna. The use of diminutive patterns in Peninsular Arabic names sometimes has a meaning related to size, but is often more readily interpretable as an onymic or transonymic pattern. The diminutive may also serve to disambiguate two similar names. Within onomastics, derivational morphology often serves the pragmatic purpose of lexical expansion, over semantic considerations. The diminutive is, therefore, polyfunctional in Arabian names. Although diminutivization of names is generally motivated from the pragmatic domain, its form and meaning are also constrained by the semantic category of the name being used. In addition, a quantitative analysis of toponyms indicates that diminutivization is more common in areas where Bedouin-type dialects are spoken.

Most of the names examined here are taken from the following sources:

• Lorimer (Reference Lorimer1908): Place names and tribal names, Khuzestan, Iraqi, Gulf, Baḥārna, Najdi, Omani and other varieties of Arabic

• Littmann (Reference Littmann1920): Personal names, Najdi Arabic and Druze Arabic

• Mandaville (Reference Mandaville2011): Plant names, Najdi Arabic

• Qafisheh (Reference Qafisheh1996, Reference Qafisheh1997): Miscellaneous, Gulf Arabic

• Holes (Reference Holes2001): Miscellaneous, Gulf Arabic and Baḥārna Arabic.

The data sources are mainly reference works such as dictionaries and glossaries. In all these works, apart from hypocoristic personal names, lexically diminutive names are frequently given as the sole citation form, in which the diminutive pattern is obligatory (see below). Diminutive frequency estimates were also obtained for Yemeni names (al-Maqḥafī Reference al-Maqḥafī2002). Hejaz and Dhofar are underrepresented in this data, but estimates covering the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula allow us to assert that the diminutive CiCēC is the most common vocalic pattern for Arabian names.

Defining “proper names”

Though proper names have special morphosyntactic properties in many languages, defining the set “proper names” is not an easy task. For Coates (Reference Coates2006: 356, 371), proper names “refer nonintensionally” and are “senseless”. Proper names may not be defined by their distinctive features – they refer, but do not denote. This article adopts the semantic-pragmatic framework given by van Langendonck (Reference van Langendonck2020), which is a refinement from the “pragmatic theory of properhood” promoted by Coates (Reference Coates2006). Van Langendonck (Reference van Langendonck2020) characterizes Coates’ approach as “reductionist”. Van Langendonck and van de Velde (Reference van Langendonck, van de Velde, Hough and Izdebska2016) offer morphosyntactic evidence that proper names may have both denotation (semantic meaning) and reference (pragmatic meaning). Indeed, the empirical data presented here do not justify a discrete boundary between semantic and pragmatic meaning. Semantics and pragmatics both play a part in the evolution of Arabian names.

Regardless of how we approach “proper names” as a linguistic category, diminutive names are very frequent in Arabic. Van Langendonck (Reference van Langendonck2020) writes that proper names cannot be treated as a determinate set. Some names are prototypically proper names and others are not; there are also language-specific differences in how names are construed. The larger part of this study, including the quantitative portion, deals with family names and place names, which are prototypically proper names (van Langendonck Reference van Langendonck2020: 117). Examples of diminutive toponyms and anthroponyms range from the earliest eras of Arabian epigraphy, through to pre-Islamic poetry and up to the present day. Names of plants (phytonyms) and wildlife (zoonyms) are also included in this study, following the typology of proper names given by van Langendonck and van de Velde (Reference van Langendonck, van de Velde, Hough and Izdebska2016: 29–39); this should not be regarded as a claim that all such terms function as proper names. Rather, terms for species, much like brand names and names of diseases, are less prototypically proper names, but many of these may function as proper names. Consider the examples:

1) ṯmām is an important grazing plant.

2) The camels discovered some ṯmām.

In example (1), ṯmām (i.e. Panicum turgidum) is a proper noun, which cannot be restricted by a relative clause; in (2) the same word is a common noun (cf. van Langendonck Reference van Langendonck2020: 118). Indeed, in their morphosemantic properties, Arabic terms for plants and wildlife are unique, sharing characteristics with both common nouns and proper nouns. They are a marginal category, but nevertheless constitute a useful and underexplored point of comparison in the study of Arabic nouns.

Many other semantic fields may include proper names, some of them diminutive, but data were too scanty to allow for a thorough analysis. For example, names of diseases may be diminutivized, e.g. šnētir “chicken pox” (Kuwaiti). Names of traditional games and dances may be diminutive – and not only when pertaining to children, e.g. mǧēlsi “men's folk singing”. Names of stars may be diminutive in Arabic, such as shēl “Canopus” and ḥaymir (< ʾuḥaymir) “Arcturus”. Names for points in time may also be diminutivized in Arabian dialects, e.g. ġbēša “early morning”.Footnote 1

Defining “diminutive” morphology in Peninsular Arabic

In my dataset for Peninsular Arabic, the most common diminutive forms fall into four groups of patterns (following Hoffiz Reference Hoffiz1995: 166; Holes Reference Holes2016: 127–8; cf. Socin Reference Socin1898).

CiCēCFootnote 2

This includes the quadrilateral forms C1iC2ēC3iC4 and C1C2ēC3īC4. These are frequently plain, e.g. qurayn “a place name” (attested 7x) < qarn “hill”, but may be inflected with the feminine suffix -a, e.g. burayda “a city” (Najd), or the nisbah suffix -ī.

Gemination of the second or third consonant occurs in plant terms and rarely elsewhere. The variant C1iC2C2ēC3 is attested in 27 names, e.g. fuṭṭaym “a family name” (Gulf); 25 such forms are plant names.Footnote 3 Mandaville (Reference Mandaville2011) also includes two plant names of the pattern C1(i)C2ēC3C3: ḥwērra “Leptaleum filifolium” (Kuwait) < ḥārr “hot” and ḥuwēḏḏān “Cornulaca monacantha” (Āl Murra) < ḥāḏ “two species of Cornulaca”.

CaCCūC

This includes C1aC2C2ūC3 (mainly in hypocoristics of given names; see Davis and Zawaydeh Reference Davis and Zawaydeh2001), C1aC2C3ūC3, quadriliteral C1aC2C3ūC4 and occasionally variants in which ū > ī, e.g. siḥtīt “extremely small pearls” (Holes Reference Holes2001) < suḥtūt.

The pattern ʾaC1C2ūC3 is a form found exclusively in Yemen. Littmann (Reference Littmann1920) also reports the form C1ayC2ūC3. In a few items, two or more diminutive forms alternate, as in banu al-ḥuḏayfī ~ ʾaḥḏūf “a tribe” (Yemen), šuwwēḫ ~ šēyyūḫ (< šayyūḫ) “globe thistle” (Najd).

Suffix -ō

The suffix -ō is much more limited in usage than the first two patterns. It is primarily attested in hypocoristics of given names (cf. Procházka Reference Procházka, Lucas and Manfredi2020: 95).Footnote 4 It also appears in nouns of “local reference”, but is no longer productive in Gulf Arabic (Holes Reference Holes and Versteegh2007: 616). It is attested in four ichthonyms (see Table 3). In northern Oman, this affix is attached to common nouns to indicate “immediacy in space” (Morano Reference Morano2019: 47), which is one of the accepted meanings of the diminutive. The suffix -ō is also a definite noun marker in Southwest Iranian languages, such as Kumzari, but none of the Arabic names ending in -ō appears to be of Iranian origin.

Suffix -ūn

Another diminutive suffix -ūn is occasionally attested in the study area. Holes (Reference Holes2005: 250) lists five examples of diminutive -ūn in common nouns and two in names, opining that it is “probably of Aramaic origin”; in data gathered for this study, diminutive -ūn was attested in one toponym, abu al-ḥanaynūn “a pearlbank” (Lorimer Reference Lorimer1908: 366).

While other patterns are sometimes considered diminutive in Arabic, e.g. CiCCaC, none of them figured prominently in the data considered here and thus they are not included.Footnote 5

“Diminutive” is taken as the typical, not exhaustive, meaning of the above patterns. I argue that in Peninsular Arabic names, diminutives have three functions in addition to existing categories of meaning: 1) marking names (onymic), 2) deriving new names (transonymic), and 3) differentiating existing names (disambiguator).

Summary of frequency data

Lorimer's Gazetteer

For the purposes of analysing the morphosemantics of Arabic proper nouns, 9,207 proper names were gathered from J.G. Lorimer's Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf (Reference Lorimer1908). Of these, 1,320 names from non-Arabic-speaking provinces of Persia were excluded. This leaves a sample of 7,887 proper names: 5,451 toponyms and 2,436 anthroponyms.

These data represent a vast area where a number of Arabic varieties are spoken, in addition to Modern South Arabian languages and Indo-Iranian languages, which are not examined here. Arabic dialects represented in the study area are primarily those categorized as North Arabian by Johnstone (Reference Johnstone1967), comprising a total of 4,847 names. Omani Arabic, Baḥārna Arabic and, to a lesser extent, Dhofari Arabic and Šiḥḥi Arabic are also represented.

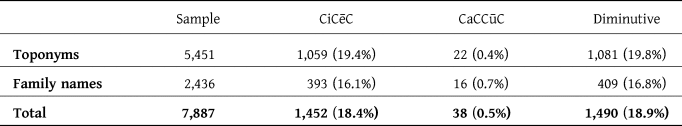

Overall frequency of diminutive morphology among these names is given in Table 1. The pattern CiCēC is quite frequent in Arabian toponyms and family names, and CaCCūC occurs occasionally; other types of diminutives are rare or unattested in data from Lorimer.Footnote 6

Table 1. Frequency of diminutive morphology in proper names

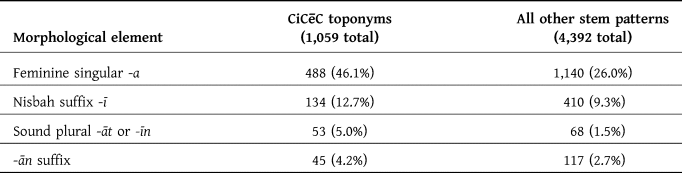

As shown in Table 2, diminutive toponyms often receive two or more suffixes (cf. Mandaville Reference Mandaville2011: 237).

Table 2. Frequency of suffixes in Arabic toponyms in Lorimer (Reference Lorimer1908)

Modern sources

In addition, zoonyms and phytonyms were gathered for comparison. Plant names were gathered from Mandaville (Reference Mandaville2011). Most names for marine fauna came from Eagderi et al. (Reference Eagderi, Fricke, Esmaeili and Jalili2019). Other wildlife names were collated into a lexical database on Gulf Arabic gathered by the author.Footnote 7 Diminutive frequencies are given from this database in Table 3.

Table 3. Frequency of diminutive morphology in Gulf Arabic names

The pattern CiCēC prevails in most onomastic categories. One exception is notable: names of land animals are generally not lexically diminutive; rather, the diminutive of size is reserved for young animals, e.g. rwēl “young ostrich” (Al-Rawi Reference Al-Rawi1990: 223).

Supplemental sources

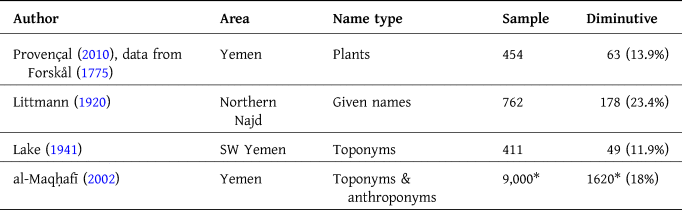

To test the above observations concerning North Arabian dialects, frequency counts were obtained from other sources (shown in Table 4). There is subregional variation, but the frequency of diminutive names is relatively consistent in the Arabian Peninsula.Footnote 9

Table 4. Frequency of diminutive morphology in other sources

Meanings of diminutive common nouns

The semantics of diminutive common nouns in Arabic varieties is relatively well-investigated. Typically, the diminutive in common nouns carries meanings listed by Jurafsky (Reference Jurafsky1996: 536): small, child/offspring, female gender, small-type, imitation, intensity/exactness, approximation and individuation/partitive. Diminutivization is frequently an optional inflection, used for politeness and endearment:

ḥilw ~ ḥlēw “nice”

ṭayrī ~ ṭwayrī “my falcon”

The pragmatic meanings of the diminutive in Arabic common nouns fall within the range of cross-linguistically well-attested expressive functions of diminutive nouns, which include endearment, contempt, “non-seriousness”, approximation and intensification.Footnote 10 In these functions, the diminutive is almost always optional.

Diminutivization may also be used in the derivation of new (common or proper) nouns. In such cases, it is not optional, e.g. ligēmāt “a type of sweet” < ligma “morsel” (Bahrain; Holes Reference Holes2001: 482).

Superficially, the optional usage of the affective diminutive in common nouns bears some resemblance to the optional usage of the hypocoristic diminutive in given names, but this relation is misleading with regard to all other types of Arabic onomastics. In a few cases, diminutivization was optional in a tribal name found in Lorimer (Reference Lorimer1908), e.g. ruwāḥī ~ ruwayḥī “a tribe”.Footnote 11 Thirteen such cases were documented among 1,490 diminutive names. The diminutive is typically optional in common nouns, but it is typically obligatory in names (Borg and Kressel Reference Borg and Kressel2001: 49; Ritt-Benmimoun Reference Ritt-Benmimoun2018). Borg and Kressel (Reference Borg and Kressel2001: 49) further point out that lexically diminutive names differ morphologically from hypocoristics which are formed by the pattern CaCCūC and suffixes -ō and -ūn, but lexically diminutive names are more commonly formed with CiCēC.

Previous accounts of diminutive names

The semantics of diminutive names is a poorly explored topic. The morphology of names is rarely treated in grammatical descriptions, and semantic studies are almost totally confined to common nouns and adjectives. Some linguists have noted the high frequency of diminutive names in Arabic, but few provide any rationale for its productivity.

Socin (Reference Socin1898: 483) dedicates about half of his study on Algerian names to the discussion of various diminutive forms, but he demurs on the question of how they came to be so productive. Palacios (Reference Palacios1942: 25) notes that the diminutive is the predominant form for Arabic place names in Spain. Johnstone (Reference Johnstone1967: 82) notes that in Gulf Arabic, the pattern fʿēlīl is found “mainly [in] proper names”. Taine-Cheikh (Reference Taine-Cheikh2018: 22–23), while noting the relative rarity of CiCēC nouns in the Middle East, notes that certain diminutives are mainly found among proper nouns. None of these studies seeks to explore diminutive names as distinct from diminutive common nouns.

In a study of Iraqi diminutives, Masliyah (Reference Masliyah1997: 77, 78) advances the conversation by trying to supply an expressive meaning in diminutive names. He points out the diminutive in terms for “wild animals…harmful plants” and “courageous tribes”. He makes a case that here the diminutive serves “to soothe the fear they may cause to people”. This is a helpful suggestion, but one that alone is not sufficient to explain the sheer abundance of diminutive tribe names and place names, as well as terms for birds, fish and plants.Footnote 12 A broader explanation is needed.

Mandaville (Reference Mandaville2011: 207) perceived that diminutives occur in plant names, place names and personal names at a “much higher frequency than in common speech over all”. Through his thorough study of plant names, he judged that the meaning of the pattern CiCēC in these names was attributive or onymic. “Diminutive forms in the plant names … appear to have the primary function not of indicating small physical size but rather of attributing the characteristics of a root noun to its referent and probably, to some extent, of marking it as a plant name.” Attribution was once a meaning of the English diminutive suffix -ling, e.g. earthling “ploughman”, darkling “dark-dwelling”. Masliyah (Reference Masliyah1997) and Mandaville (Reference Mandaville2011) are both right in suggesting that CiCēC has various senses and functions driven by both semantics and pragmatics.

Semantic meanings of diminutive names

Size-related meanings

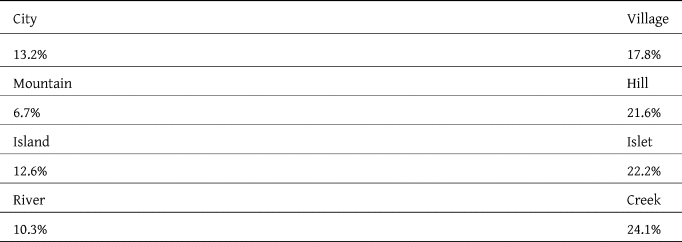

If we organize types of toponyms according to size, as in Table 5, we see that the diminutive is more frequent in microtoponyms, but it is still relatively frequent in names referring to places of all sizes. The conventional size-related meaning of CiCēC may account for many diminutive geonyms, for instance, but it does not explain the diminutive as a preferred form in every semantic category.

Table 5. Frequency of diminutive morphology in toponyms, by size

Expressive meanings: affection and contempt

Affective meaning has explanatory power in its optional, expressive use of the diminutive in given names, which follow the pattern CaCCūC (e.g. il-yāziyeh ~ yazzūy “female given name”, UAE), and in common nouns, which follow CiCēC (e.g. ṣḥēn ~ ṣaḥan “plate”), but this expressive use of the diminutive is rarely attested in any other type of name in Peninsular varieties of Arabic. Affective interpretations are particularly unsatisfying with regard to lexically diminutive names of tribes, clans, families, settlements, flora and fauna.

In a study of personal names, Borg and Kressel (Reference Borg and Kressel2001: 49) reject the contention that lexically diminutive personal names are used for endearment. Rather, diminutive names are used among Bedouin tribes to avert the attention of the evil eye and prevent death by making the child appear lowly. Borg and Kressel support this with an anecdote of a Bedouin man who gave his children contemptuous names after his first children died young. Death prevention names are a well-known practice in West Africa but have not been studied in Arabic.

The following names are listed in Littmann (Reference Littmann1920), which mainly treats northern Najdi Arabic:

il-ʿaryān “Naked”

miġḍib “Annoyance”

ḥimār “Donkey”

duwēč “Rooster (dim.)”

sakrān “Drunk”

skēkīr “Drunk (dim.)”

This apotropaic function of (lexically) diminutive names is quite distinct from the diminutive's (usually optional) hypocoristic usage and should be explored in more detail in anthropological investigations of Arabic personal names. If it is correct, the diminutive in this context signifies contempt, not affection. The pattern CiCēC may denote endearment in common nouns, but contempt in given names; the pattern CaCCūC denotes endearment in given names, but has no clear function in common nouns.

It is unclear what influence, if any, apotropaic naming practices have in Arabic proper names other than personal names. It is conceivable that the diminutive could serve an apotropaic function in Peninsular Arabic place names. Thus far, evidence only points to this usage for death prevention after the birth of a child.

Partitive and individuative meanings

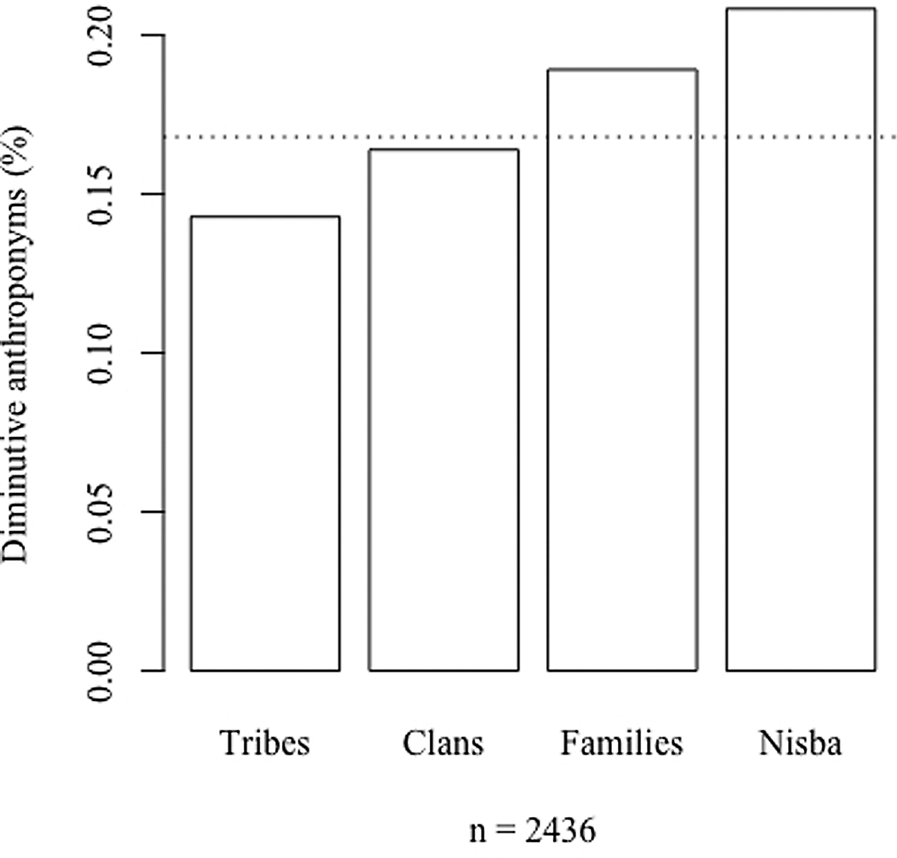

In data from Lorimer (Reference Lorimer1908), diminutive names are common for tribes (14.3 per cent), although they are more common in names of sub-tribal groups (17.1 per cent; see Figure 1). In a few names, the diminutive may have a partitive meaning, e.g. ʾāl ʿaǧayma “section of Ajmān tribe” < ʿaǧmān “a tribe”.

Figure 1. Frequency of diminutive morphology in anthroponyms, by relative size

Diminutives are even more frequent in singular (nisbah) forms (20.8 per cent), indicating a possible individuative or attributive meaning. A diminutive nisbah is often derived from a group name that is not diminutive, e.g. salaiṭī “member of the Sulaiti tribe” (< suluṭa), suwaydī “a member of the Suwaidi tribe” (< sūdān), muḥayribī “member of the Maḥāriba clan” (< maḥāriba).

Here we are only noting tendencies, though, and we have not arrived at a comprehensive account of diminutive names. Moreover, in two cases, the plural or collective form is diminutive and the nisbah form is not, e.g. ġāfilī “member of the Ghafailāt” < ġafaylāt “tribe name”.Footnote 13

Attributive meanings

Sībawayh (Reference ʿUthmān1988) wrote that use of the diminutive form can denote something “similar to the thing you are uttering while you mean something else” (Fayez Reference Fayez1990: 201). In Mandaville's (Reference Mandaville2011) account of Najdi plant names, diminutivization frequently denotes some similarity, whether visual or sensory, e.g. gnēfiḏa “Anastatica hierochuntica” < ginfiḏ “hedgehog”, khiyyēs “stinkweed” < khāyis, “stinking”, ʿuwēḏirān “little ʿāḏir-like bush” (Artemisia scoparia) < ʿāḏir “Artemisia monosperma”. Attributive meanings are also possible in other types of names, e.g. hadhūd “a tribal name” (attested twice) < hudhud “hoopoe”, fahayd “a tribal name” (attested 4x) < fahad “lynx”. In spite of these semantic interpretations of the diminutive, pragmatic meanings are able to account for a wider array of data.

Pragmatic meanings of diminutive names

Diminutive as onymic

Aside from Arabic, several languages abound in diminutive names in which the diminutive affix may be semantically vacuous. Morris (Reference Morris2002: 49) indicates the diminutive in Soqoṭri plant names may have semantic meaning, denoting smallness, or pragmatic meaning, merely deriving a new form. Alexandre (Reference Alexandre2015: 51) writes that in Kimbundu, diminutive and augmentative suffixes are common in toponyms, but lack their conventional meanings. Similar examples may be adduced in Persian (Imani and Kassaei Reference Imani and Kassaei2016). Nash (Reference Nash, Clark, Hercus and Kostanski2014: 45) writes that, in Yuwaalayaay and Yuwaalaraay toponyms, the diminutive suffix -dool acts as a “definitiser or individuator, related to its hypocoristic function and the formation of proper names”. In existing onomastic terminology, the diminutive in these languages acts as an onymic, a name marker.

A point of evidence for CiCēC as an Arabic onymic pattern is the adaptation of borrowed names: the Persian toponym ḫargū “an island” is Arabized as a diminutive, ḫwēriǧ. From pre-Islamic times, there is a tendency to diminutivize names during borrowing, including prophets’ names, e.g. ʿuzayr “Ezra” and sulaymān “Solomon”. Even the title firʿawn “pharaoh” is attested as a diminutive, furayʿ.

Diminutive as transonymic

Mandaville (Reference Mandaville2011: 237) writes that diminutivization often occurs in deriving toponyms from plant names. In onomastics, the derivation of one name from a name of another type is known as transonymization. In eastern Arabia, the four major categories form a cline of derivation, zoonym > phytonym > toponym > anthroponym, with transonymization frequently inducing diminutivization.

Zoonym > phytonym

ḫanzīr “pig” > ḫinēzīr “Peganum harmala”

Phytonym > toponym

ḥanẓal “the colocynth gourd” (Citrullus colocynthis) > ḥanayẓil “a village”

Zoonym > toponym

ẓabb “spiny-tailed lizard” > ẓabayba “a well”

Phytonym > anthroponym

rimṯ “a saltbush” (Haloxylon salicornicum) > rumaiṯī “a tribe”

Zoonym > anthroponym

ḥanaš “poisonous snake” > ʾāl ḥanayš “a tribal section”

In many such examples, it is unclear whether the diminutive is primarily attributive (semantic) or transonymic (pragmatic). It is also possible that the diminutive derives new (secondary) names within the same semantic field, as suggested in Galician toponyms by Pérez Capelo (Reference Pérez Capelo2017). However, this is not clear from the data.

Diminutive as disambiguator

Early theorists referred to proper names as having unique reference; problematically, though, multiple referents may share the same name. Moldovanu (Reference Moldovanu1972: 82) noted a tendency to reuse toponyms across different semantic fields, but to differentiate toponyms when repeated within the same semantic field. Differentiation is usually accomplished by compounding in English, e.g. Upper Wraxall ≠ Wraxall, Little Sodbury ≠ Old Sodbury, Bradford-on-Avon ≠ Bradford. In other languages, the same aim is accomplished by a derivational affix, frequently with a diminutive or attributive meaning, e.g. among Roman cognomina, Crispinillus ≠ Crispinus ≠ Crispus. Efficiently differentiating or disambiguating names appears to be a key function of diminutivization in Arabic names.

In wildlife terms, the diminutive may differentiate two nouns, without a clear small-type/normal-type correspondence, e.g. gabgūb “lobster” ≠ gubgub “small crab”, ḥwēt “oyster” ≠ ḥūt “whale; fish” (generic). Among toponyms, numerous pairings may be found, e.g. dbayy “a city” ≠ diba “a village” (UAE); kuwait “a city” (Kuwait) ≠ kūt “a town” (Iraq). Lorimer's (Reference Lorimer1908) data included at least 63 such pairs (out of 1,081 diminutive toponyms). Other diminutive names have a corresponding non-diminutive name that is not listed by Lorimer, e.g. simaysima “a village” ≠ simsima “well” (Qatar).

In a study of Canarian diminutive toponyms, Trapero (Reference Trapero, Corrales and Corbella2000) writes that the purpose of derivational (i.e. diminutive) morphology in these toponyms is lexical expansion; semantics are not even in consideration.Footnote 14 In Arabian names, I contend that the diminutive frequently serves the same purpose.

Caskel's study of Ibn al-Kalbī's Ǧamharat al-Nasab (Reference Caskel1966, vol. 1: fig. 19) includes a single family with three sets of brothers differentiated by diminutivization: ḫālid ≠ ḫuwaylid, ṭālib ≠ ṭulayb and al-ḥāriṯ ≠ al-ḥuwayriṯ (cf. Borg and Kressel Reference Borg and Kressel2001).

The same process occurs among tribal names. Tribal sections with adjacent lineages are differentiated using the diminutive. In the three examples below, the sections with diminutive names are larger in number than those with non-diminutive names.

ʾāl bū ḥamādi ≠ ʾāl bū ḥumaydi ≠ ʾāl bū ḥamūd

ʾāl bū ḫāṭar ≠ bayt ḫuwayṭar

ṭarārifa ≠ ʾāl ṭarayf

This is similar to Jurafsky's (Reference Jurafsky1996) category “approximation” and Mandaville's (Reference Mandaville2011) function of attribution. However, it is (pragmatic) disambiguation, not (semantic) approximation, that is motivating the use of the diminutive in these names.

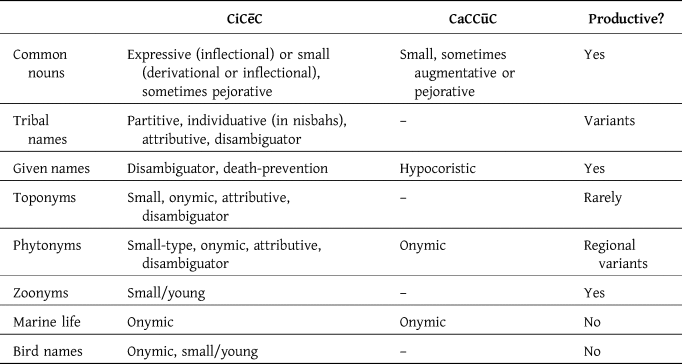

Synthesizing the data, it becomes apparent that the range of meaning of diminutive morphology in Arabic nouns is circumscribed according to the semantic field of the noun (Table 6). If the meaning of a morpheme is limited by semantic domain, even among proper nouns, then proper nouns are able to both refer and denote.

Table 6. Meanings of the Arabic diminutive, by semantic category

Diachronic evidence

Diachronic evidence further bears out the semantic-pragmatic account of diminutivization. According to Johnstone and Wilkinson (Reference Johnstone and Wilkinson1960: 442), the name “Core Hessan” (ḫōr ḥassān, a bay and settlement) was recorded in 1827 in Qatar. In 1908, Lorimer listed ḫōr ḥassān on the west coast, and ḫōr šaqīq on the east coast. Lorimer (Reference Lorimer1908: 681) wrote that one name became diminutivized to disambiguate the two: “[Khor Hassān] is frequently spoken of simply as ‘Khuwair’ in contradistinction to ‘Khor’ [= Khor Shaqīq].” He uses the names ḫōr ḥassān, ḫwayr ḥassān and ḫuwayr interchangeably, but by 1960, the names of both bays were shortened, and today the standard names are al-ḫuwayr and al-ḫawr. It is likely that in such pragmatic re-namings, it would be inadmissible to diminutivize the larger place name; thus, semantics and pragmatics both determine the acceptability of the name.

Several other name variants have been lost to standardization. For example, Lorimer (Reference Lorimer1908: 281) lists a valley known as both bāṭin and baṭayn; today, it is known as bāṭin (NE Saudi), perhaps because buṭayn designates another (smaller) valley in Najd. One diminutive toponym, rās al-ǧunayz “a cape” (Oman), is today falling out of use, in favour of rās al-ǧinz. These show the ongoing influence of pragmatic concerns in name evolution.

Scope

In compound names, the diminutive may apply to either element or both, suggesting that the name is the scope of the diminutive. Lorimer includes two cases of diminutive agreement between a generic element and a proper noun: falayǧ bin qafayyir “a hamlet” (Hatta), and ʿawaynat bin ḥasayn “a group of wells” (Qatar).Footnote 15 Cross-linguistically, diminutive agreement is unusual, but it is obligatory in Maale and Walman (Steriopolo Reference Steriopolo2013: 42).

In several cases, only the generic element of a place name is diminutive, e.g. qarayn aḏ-ḏabbān “well” (Bahrain), ʿawaynat aš-šuyūḫ “camping ground” (Qatar), muwayh ḥakrān “group of wells” (Hejaz). Kharusi and Salman (Reference Kharusi and Salman2015) note diminutive terms used in Omani hydronyms, including some with no clear relation to size, e.g. kudayr “turbid (water)”, mudayfiʿ “lower part of a valley”. Similarly, Qafisheh (Reference Qafisheh1997) lists šʿēb “small valley”, but šiʿb has the same meaning. These diminutive generics and attending diminutive agreement may have arisen through variation in the scope of the diminutive.

Quantitative analysis

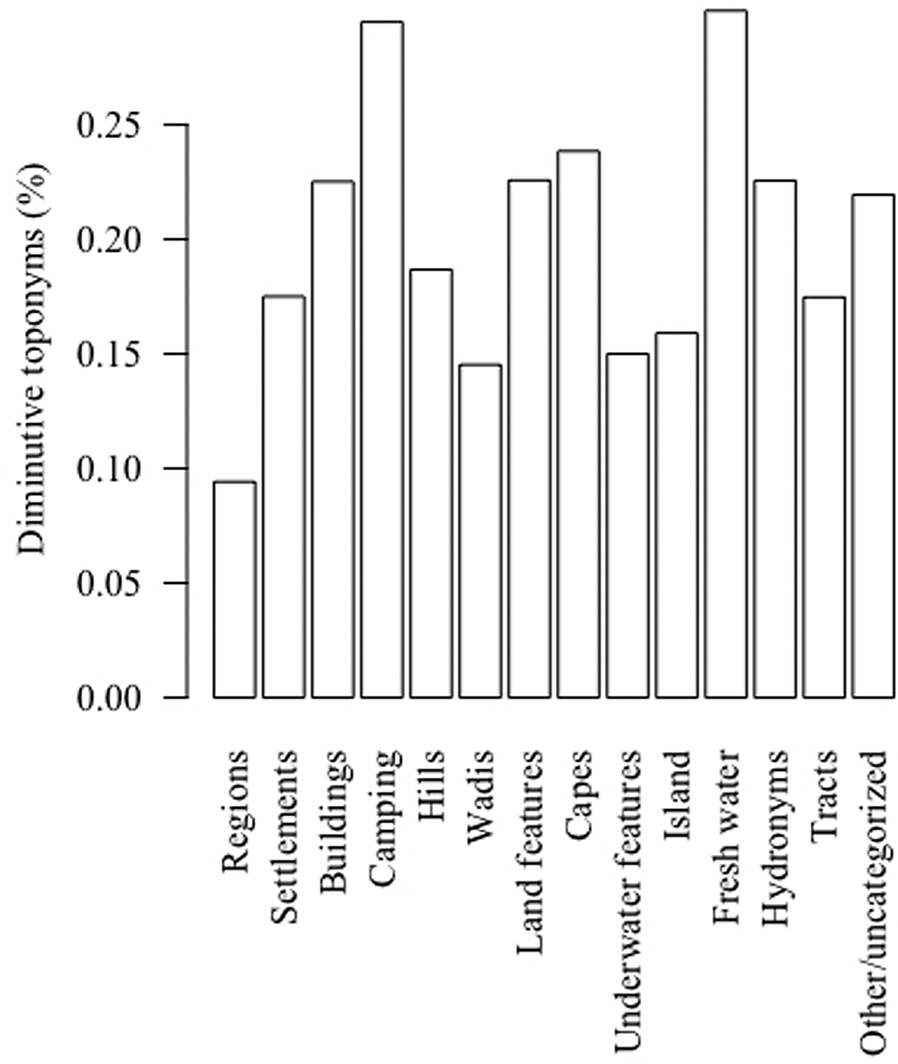

Physiography

CiCēC applies frequently in names of sources of fresh water (Figure 2). Many of the most frequently used roots among toponyms were related to water sources: m-l-ḥ “salt” (18x), š-ʿ-b “rivulet” (15x), b-d-ʿ “spring” (17x), ṣ-f-w “pure” (13x), m-r-r “bitter” (13x), f-l-ǧ “irrigation channel” (10x).

Figure 2. Frequency of diminutive morphology in toponyms, by type

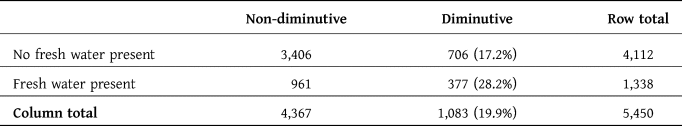

A chi-squared test was performed to test the relation between diminutivization and fresh water sources (Table 7).Footnote 16 The relation is statistically significant, Χ 2 (1, N = 5450) = 76.124, p < .001.

Table 7. Frequency of diminutive names, by presence or absence of water

Bedouin and sedentary dialects

Kaye and Rosenhouse (Reference Kaye, Rosenhouse and Hetzron1997: 284) have claimed that “diminutives are used mainly in Maghrebine and bedouin (and bedouinized) dialects in both nouns and adjectives”. Borg and Kressel (Reference Borg and Kressel2001) likewise note a special use of the diminutive in Bedouin societies. In data from Lorimer (Reference Lorimer1908), the diminutive form bears a geographic relation to Bedouin-type dialect areas.Footnote 17

To test the strength of this relation, regions were coded according to whether the historically prevailing Arabic dialect of the region is a Bedouin-type dialect or a sedentary-type dialect (see Figures 3 and 4). The imprecise coding of whole regions as “Bedouin-type” or “sedentary-type” requires some explanation. I follow Lorimer's geopolitical terminology.Footnote 18 The geopolitical categorization of toponyms here acts only as a proxy for which type of dialect is taken to be the prevailing source language for toponymy in that area based on present and historical realities. With regard to Arabistan (Khuzestan), I consulted Lorimer's notes about population groups, wherein he notes the prevalence of Bedouins in South Arabistan, but not in North Arabistan (Lorimer Reference Lorimer1908: 124). He also notes an abundance of Bedouins in Oman Proper (Lorimer Reference Lorimer1908: 1376). Even though Gulf Arabic (a Bedouin dialect) predominates in Bahrain, it is coded as a sedentary-type area because of the strong historical presence of the Baḥārna. Lorimer (Reference Lorimer1908: 238) writes that the historically agriculturalist Baḥārna are the “largest community” in Bahrain, and Baḥārna Arabic is considered the variety more pertinent for understanding the nation's toponyms relative to other areas of the Gulf (cf. Holes Reference Holes2001: xxv; Holes Reference Holes, Arnold and Bobzin2002).

Figures 3 and 4. Frequency of diminutive toponyms in Bedouin and non-Bedouin areas

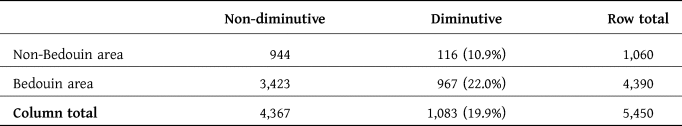

A chi-squared test was performed to test the relation between diminutivization and areas where Bedouin-type dialects are dominant (Table 8). The relation is statistically significant, Χ 2 (1, N = 5450) = 65.184, p < .001.

Table 8. Frequency of diminutive names, by historically prevailing dialect type (Bedouin or sedentary)

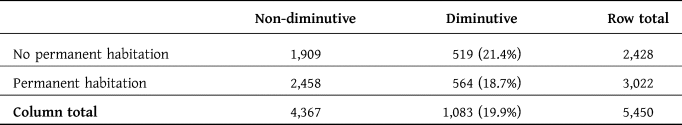

A chi-squared test was performed to test the relation between diminutivization and permanent habitation (Table 9). Permanent habitation was coded based on whether Lorimer (Reference Lorimer1908) notes permanent dwellings in a place; his notes usually include detailed information about the types of dwellings in each locale, whether temporary, seasonal or permanent. The relation is statistically significant, Χ 2 (1, N = 5450) = 6.052, p = .014.

Table 9. Frequency of diminutive names, by presence or absence of permanent habitation

Permanently inhabited locations have a somewhat lower prevalence of diminutive names. Microtoponyms associated with Bedouin practices and roles in Arabian society also have very high frequency of diminutives; this includes wells (31.7 per cent), camping grounds (29.6 per cent) and forts (29.6 per cent). This study provides strong evidence showing that places historically associated with Bedouins have a significantly higher prevalence of diminutive toponyms. The use of the diminutive in onomastics is found throughout the Arabian Peninsula and in many other Arabic-speaking regions, but the extended use of the diminutive in the pragmatic domain of onomastics may be a characteristically Bedouin practice.

Conclusion

A review of a considerable database of secondary data has suggested that the Arabic diminutive, when applied to names, has several possible meanings seldom mentioned in previously published literature, including attribution, partition and individuation. The evidence presented here also demonstrates that, in many cases, the diminutive form functions as an onymic, transonymic or disambiguator, and that these functions are attested most extensively in Bedouin-type varieties of Arabic. The relevant categories of meaning are delineated according to the semantic field at hand, indicating that names indeed have denotation as well as reference (van Langendonck and van de Velde Reference van Langendonck, van de Velde, Hough and Izdebska2016). The evolution of Arabic names, in which the diminutive may be either applied or removed, shows that both semantic and pragmatic considerations remain relevant even after name bestowal.

The use of the diminutive in marking, deriving and differentiating names should be incorporated in refining theoretical explanations of the diminutive. The link between evaluative morphology and onomastics, observed in many languages, merits more investigation on a broader linguistic basis.

Acknowledgements

This article was greatly improved by comments from a panel chaired by Professor Janet C.E. Watson at the Arabic Linguistics Forum in 2020. For other assistance with the draft of this article, I would like to thank Bishoy Habib Rizk, James Bejon of the University of Cambridge and Dr Michael Ewers of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.