1. Introduction

This article addresses the alleged difference between diachronic and synchronic palatalization by examining the palatalizing effect of the suffix *-i̯a(ka)- in Khotanese action nouns, gerundives, and verbal adjectives.Footnote 2 It shows that diachronic palatalization conforms to the model proposed by Doug Hitch (Reference Hitch1990) for synchronic palatalization (§2). Since the Old Khotanese noun jsīna- “killing” appears to be the only word to violate this model, the widely accepted etymology proposed by Ronald E. Emmerick (Reference Emmerick1969, < * Ir. *ǰan-i̯a-) is rejected in favour of a derivation from the PIE reduplicated stem *gwhé-gwhn-, so far only attested in YAv. jaɣn-, Gk. πεφνε/ο-, and possibly in Ved. jíghnate (§3). Section 3 also features other nominal and verbal derivatives belonging to the word family of the Khotanese verb jsan-: ppp. jsata- “to kill, slay”.

2. Palatalization in the Khotanese action nouns and verbal adjectives in *-i̯a-

In a recent article, Mauro Maggi and I dealt with the Khotanese masculine substantive saña- “artifice, expedient, means, method” (Del Tomba and Maggi Reference Del Tomba and Maggi2021), rehabilitating an old etymology proposed by Ernst Leumann (Reference Leumann1933–36: 510), who reconstructed an action noun in *-i̯a- derived from the Indo-Iranian root *sćand- “to appear, seem (good)” (cf. Av. ¹saṇd-, OP θand-, Skt. chand-).Footnote 3 This type of action noun was no longer productive in Khotanese and is found in a comparatively small number of substantives, typically derived from the full grade of the root (rarely on a lengthened grade).Footnote 4 Examples are kīra- “action, deed” < Ir. *kar-i̯a- and allegedly jsīna- “killing” < Ir. *ǰan-i̯a- (KS 297–9 with references). However, if we compare these two nouns with saña- < Ir. *sćand-i̯a-, the problem of the divergent treatment of palatalization comes to light, because the palatalizing effect of the suffix *-i̯a- apparently caused the umlaut of the root-vowel in e.g. kīra- and jsīna-, while it surfaced as palatalization of the consonant group *-nd- > *-n- preceding the suffix in saña-. In our article, we mentioned this problem without attempting an explanation: “[n]otice that *-i̯a- palatalizes the preceding *-n- < Ir. *-nd- in saña-, but the previous *-a- in jsīna-” (Del Tomba and Maggi Reference Del Tomba and Maggi2021: 213, n. 86).

A thorough account of synchronic palatalization in Old Khotanese has been provided by Hitch (Reference Hitch1990). To put it concisely, when a palatalization-triggering suffix is attached to a lexical morpheme, four mutually exclusive effects of potential palatalization moving backwards towards the stressed vowel may occur:

1. if the final sound of the lexical morpheme is a palatalizable consonant (or consonant cluster), it takes palatalization (e.g. 2sg.prs.act. pulśä from puls- “to ask” + -iä [SGS 192]);

2. if the final sound of the lexical morpheme is already palatal, it absorbs palatalization (e.g. 2sg.prs.act. sājä from sāj- “to learn” + -iä);

3. if the final sound of the lexical morpheme is a consonant or a consonant cluster that cannot be palatalized, it transmits palatalization and causes the umlaut of the vowel (e.g. 3sg.opt.act. kṣīma from kṣam- “to endure” + - ia [SGS 207]);

4. if the final sound of the lexical morpheme can transmit palatalization but the vowel is already palatal, the vowel absorbs the umlaut potential (e.g. 2sg.prs.act. bremä from brem- “to weep” + -iä).

Since Hitch's primary focus was on describing synchronic palatalization, he deliberately excluded sections of Khotanese inflection and derivation that are no longer productive as early as the Old Khotanese period. These include (1) abstract nouns in *-i̯a(ka)-, and (2) deverbal adjectives and (old) gerundives in *-i̯a(ka)-. It is therefore worthwhile to closely examine these derivational suffixes to determine whether additional diachronic rules can be identified.

I initially verified whether the fate of these suffixes was regulated by a Khotanese version of Sievers’ law, according to which a distinct outcome of the same suffix would be mirrored by a different realization of the palatalization: *-i̯a- after a light syllable and *-ii̯a- after a heavy syllable, including those syllables ending with a consonant cluster. Accordingly, Khot. jsīna- “killing” < *dzani̯a- < Ir. *ǰan-i̯a- would show umlaut of the vowel because *-i̯a- was attached to a light syllable (cf. also Khot. āysīra- “armour” < *azari̯a- < Ir. *ā-ȷ́ar-i̯a- or Khot. kīra- “action, deed” < Ir. *kar-i̯a-), while Khot. saña- “artifice” < *tsann-ii̯a- < Ir. *sćand-(i)i̯a- would show palatalization of the consonant because *-(i)i̯a- was attached to a heavy syllable (cf. also Khot. auśa-, ośa- “evil, bad” < *āuzii̯a- < Ir. *ā-uaȷ́-(i)i̯a-, Khot. rrāśa- “rule; domain” < *rāzii̯a < Ir. *rāȷ́-(i)i̯a-). However, Sievers’ law cannot account for several counterexamples in deverbal adjectives and old gerundives in *-i̯a-.

Only a few gerundives formed with -i̯a- are found in Khotanese. Most of them are based on verbal roots ending in -r- and having -ā- as the root vowel (SGS 216–218; KS 299b–300a). Since the -r- cannot be palatalized, it allows palatalization to go back to the previous vowel segment (e.g. tcera- “to be done” < *čār-i̯a- not *čār-ii̯a from *kar- “to do”).Footnote 5 This indicates that -i̯a- palatalizes any stressed vowels when the consonant cannot be palatalized but can transmit palatalization. Another relevant form is the old gerundive hvaña- “to be spoken” < *hu̯ani̯a- ← *hu̯an- “to call” (cf. YAv. xvan- “to sound”, MMP xwʾn- “to call”, MSogd. xwʾn-, BSogd. xwn-, CSogd. xwn- “to call, cry”).Footnote 6 Khotanese hvaña- “to be spoken” demonstrates that *-i̯a- regularly palatalizes a preceding consonant and does not cause umlaut of the root vowel (i.e. **hvīna-), contrary to what one would have expected if the different development of saña- and jsīna- were conditioned by Sievers’ law. Similar cases can be found in the passive forms of verbs, e.g. kañ- “to be thrown” < Ir. *kan-i̯a- (SGS 22; EDIV 229–31), jsañ- “to be slain” < Ir. *ǰan-i̯a- (SGS 37; EDIV 224–5), and in the causatives, e.g. vahīys- “to descend”: vahīś- “to make descend” (SGS 122), ysah- “to cease” (SGS 112): yseh- “to give up” (SGS 114).

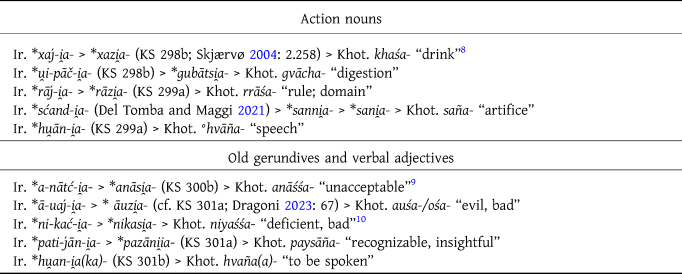

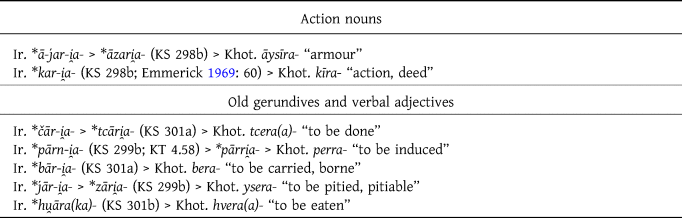

Hence, it appears that diachronic palatalization aligns with the model proposed by Hitch (Reference Hitch1990) for synchronic palatalization, as shown in Tables 1 and 2.Footnote 7

Table 1. Palatalizable morpheme-final consonant segment → palatalization of the consonant segment

Table 2. Non-palatalizable morpheme-final consonant segment → palatalization of the stressed root vowel

In light of the above, it is clear that the word requiring explanation is not saña- “expedient” but rather jsīna- “killing”, as it is the sole action noun that deviates from the palatalization rules.

3. Khotanese jsīna- “killing” and related words

The etymology of the hapax legomenon jsīna- “killing” < *ǰan-i̯a- has been proposed by Emmerick (Reference Emmerick1969: 60; Studies 1.47–8) in order to elucidate a difficult passage from the Book of Zambasta:Footnote 11

Z 13.124

hori pracaino cu ro jsīnä—na hamaraṣṭo pathīyä

rre mahādevä mahāsama—tä tteri dāru jutāndä

“It is because of liberality and also because he has always refrained from taking life that King Mahādeva (and King) Mahāsaṃmata lived so long.”

This passage exemplifies two of the five reasons for a long life in saṃsāra. The five reasons, listed in the preceding two verses (Z 13.122–3), are: (1) abundant food donation; (2) avoidance of killing; (3) meditation on the ārūpyasamāpatti (formless states of meditation); (4) practice of the four r̥ddhipādas (bases of psychic power); (5) obtainment of the dharmakāya (body of the dharma). They are explained and exemplified in the following verses (Z 13.124–7), starting with (1) abundant food donation and (2) avoidance of killing, which are condensed in v. 124.

Emmerick's exegesis of the passage is undoubtedly correct and represents a significant advance compared to Leumann's and Bailey's interpretations of jsīnäna as an instr.abl.sg. masculine of the otherwise feminine noun jsīnā- “life” (< Ir. ǰai̯anā-, cf. Tum. tsenā-),Footnote 12 whose instr.abl.sg. is expected to be jsīñe jsa: cf. Leumann's interpretive translation of cu ro jsīnäna hamaraṣṭo pathīyä as “und auch (der andere) was [weil] von dem (ihm beschiedenen) Lebensquantum rechtschaffen [edelmütig] (zu Gunsten eines Andern einst) er abgestanden ist [auf die Fortdauer des eigenen Lebens verzichtet hat]”Footnote 13 and Bailey's translation of jsīnäna … pathīyä as “withdrawn from life”.Footnote 14

Although the context demands the interpretation of the masculine noun jsīna- as “killing”, the morphophonological problems highlighted in the preceding paragraph rule out a derivation from *ǰan-i̯a-.Footnote 15 Other possibilities must be explored.

There is no doubt that we are dealing with a nominal form belonging to the word family of the verb jsan-: ppp. jsata- “to kill, slay” (SGS 37). The following are attested:

1. Adjectival compound member with -aa- < -aka-, °jsanaa- “killer” (KS 20b):

IOL Khot 160/1 v3 (KT 5.106, p. 41; Cat. 358) caṇḍāla hvąʾnda-jsanā ttāʾte “murderers, man-killers, thieves”.

2. Agent noun with -āka-, jsanāka- “killer” (KS 46b):

Sudh 94 ms. P mahaidrrasaina rre vā jsanāka paśāvai (= ms. A mahaidrasai rre vų̄-vā jsinākä paśāve; ms. C mahadrrasaina rai vā-vā jsanāka paśāvai) “King Mahendrasena has sent hither a killer against me”.Footnote 16

JS 93 (21 v3) āta ttā tvī va asidūna jsanāka “Evil killers came then against you”.Footnote 17

3. Action noun with -kyā-, jsaṃgyā- “killing” (KS 203b):Footnote 18

Suv 2.9 jsaṃgye jsa pathaṃka “Refraining from killing”.Footnote 19

Suv 2.10 jsaṃgye jsa . pathīyä “refrained from killing”. Suv 2.59 [pa]thīyä jsaṃgye jsa “id.”.

4. Derived adjective in -ia-, jsīñaa- “condemned to death” (KS 303a), on which see the main text below.

5. Gerundive in °āña-, jsanāña- “to be slayed” (KS 59b):

Sudh 314 ms. C kāḍara jse vara ṣṭau raysga vīra jsanauña (= ms. B kāḍara birre raysaga vīra jsanauña) “Then she must be slayed swiftly with his knife”.Footnote 20

Sudh 319 ms. A kāḍąrinai vara ṣṭāṃ raysgi vī jsaną̄ñä “There he must swiftly slay her with his sword”.Footnote 21

IOL Khot 147/1 r3 (KT 5.180, p. 87; Cat. 330) jsanāñä ṣi ājaviṣi “that snake must be killed”.

6. Infinitive formed from the present stem with -ä, jsanä “killing, to kill” (KS 292a):

Rāma 177a varai āṣṭaṃdāṃdä jsąnä “They were about to slay him there”.

IOL Khot S. 13 70 (KT 2.9, p. 45; Cat. 511) cv-aṃ hvaihura biśä āṣṭaṃdāṃdä jsąnä “because the Uigurs began killing them all”.Footnote 22

7. Infinitive formed from the stem of the past participle with -ie, *jsīte > jsīye “killing, to kill” (SGS 37, 219; KS 287a):

Z 24.442 cīyä rre hvadu . hamatä jsīye parīyi “when the king himself orders to kill a man”.

Z 24.450 cvī ye jsīye parītä “when one orders to kill one”.

The latest form (7) is a good candidate to account for jsīnäna in Z 13.124. Indeed, the expected infinitive from the stem of the past participle of jsan- must have been jsīte; the spelling -y- (cf. jsīye) for -t- is ubiquitous since the Old Khotanese period (cf. parīyi in Z 24.442 and parītä in Z 24.450 above). Therefore, a possible explanation involves a slight emendation of the manuscript reading from jsīnäna to *jsītäna “from killing”, an infinitive formed from the past participle inflected as instr.abl.sg. The proposed emendation does not present significant obstacles, as -n- and -t- are very similar in Khotanese Brāhmī and, in the aforementioned passage from chapter 13 of Z, inflected forms of the noun jsīnā- “life” (and derivatives) occur nine times in the space of eight verses (nom.sg. jsīna 122, 125 [2×], 126 [2×], 127; nom.acc.pl. jsīne 128, jsīnä 128; adjectival compound nom.acc.pl. dāra-jsīniya “long lived”, 129). Although a copying error remains a possibility, it is possible and certainly safer to keep to the manuscript reading jsīnäna.

The origin of jsīna- cannot be clarified without taking into consideration the adjective jsīñaa- (4), which Degener (KS 303) translates as “zum Tode verurteilt” and derives from the noun jsīna- “killing”. As I have demonstrated, however, jsīna- cannot be from *ǰani̯a- and we therefore need to explain its apparent derived adjective accordingly. Khotanese jsīñaa- is attested four times:

1. acc.sg.m. Z 15.43 (OKhot.) maharaṃggu jsīñau hvaṃʾdu ṣṣai hīśśanä khastu ne yīndä “The condemned athletic man even iron cannot wound”.Footnote 23

2. gen.pl.m. KV 2.5 (OKhot.) IOL Khot 175/3 v3+FK 210.21 Do.33 v3 u pūhä ṣä ku jsī#ñānu hvaṃʾdānu bājä hvāñäte “And the fifth is when he pronounces deliverance of men condemned to death” (= Skt. vadhya-prāptānām manuṣya-paśu-sūkara-kukkuṭādīnām parimocanam).Footnote 24

3. nom.pl.m. Suv 3.78 (LKhot.) cu jsīñā rruṃdä parauya “Those who are to be slain at the king's command” (= Skt. ye rāja-caura-śaṭha-vadhya-prāptā).Footnote 25

4. nom.pl.m. Suv 3.78 (LKhot.) cu jsīñā tti haṃphūsīde jīyina “May those who (were) to be slain have a share in life” (= Skt. vadhyāś ca saṃyujyiyu jīvitena).Footnote 26

As can be seen, the inflected forms of jsīñaa- can consistently be translated as “to be slain” in all four occurrences, suggesting their use as the gerundive of jsan- “to slay, kill”. Indeed, Bailey (Prolexis 92) considered this jsīñaa- to be the gerundive form of jsan-, a theory also supported by Skjærvø (Reference Skjærvø2004, 2: 269). As for the apparent palatalization of both the consonant and the vowel, an obvious hypothesis is that the gerundive suffix *-i̯a- could have palatalized not only the stem-final consonant °n- > °ñ- but also the stressed vowel via umlaut.Footnote 27 So-called “double umlaut” might have occurred to prevent homophony with other conjugated forms of the passive verb jsañ- “to be slain”.Footnote 28 Nevertheless, instances of double umlaut are exceedingly rare.Footnote 29

In order to explain the ī-vowel in jsīñaa-, a different, more plausible solution can be proposed based on comparative grounds. Vedic has a reduplicated present jíghnate, whose precise origin is debated: it may either derive from IIr. *ǰi-ghn- < PIE *gwhi-gwhn-, or have acquired the i-vowel analogically after other present formations of the type Cí-CCa-.Footnote 30 If the same form had also been inherited by Khotanese, then the following diachronic path could be established: IIr. *ǰighn- > Ir. *ǰign- > *ǰiɣn- > *dzīn- (loss of *ɣ and compensatory lengthening) → ger. *dzīn-i̯a- > Khot. jsīña(a)-. However, a serious problem with this derivation is that the sequence *ǰi/ī- was expected to yield Khot. ji- (cf. intransitive pasūjs- “to burn” < vs. causative pasūj- “to light”, kaljs- “to be struck” vs. causative kalj- “to strike” or the denominal verb haṃgūj- “to meet” from haṃgūjsa- “meeting”).Footnote 31

In Indo-European languages, an intensive form of PIE *gwhen- “to strike” (LIV2 218–9, Gk. θείνω, Lat. de-fendō, Skt. hánti, YAv. haiṇti, etc.) is attested in the reduplicated form PIE *gwhé-gwhn- “to strike repeatedly” → “to kill” (cf. YAv. jaɣn-, attested twice in Yt. 13.45 ni-jaɣnəṇte [3pl.prs] and Yt. 13.105 auua-jaɣnat̰ [3sg.aor.], Gk. πεφνε/ο-).Footnote 32 Therefore, it is worth considering whether an inferable stem *jsīn- could also be the outcome of IIr. *ǰa-ghn- (cf. YAv. jaɣn-) < PIE *gwhé-gwhn-. In fact, there is evidence suggesting that in the sequence Ir. *-agC- > *-aɣC- the voiced fricative yielded *i̯ in pre-Khotanese, eventually forming a diphthong with the preceding vowel, which later monophthongized, cf. Ir. *sagra- > *saɣra- (MMP sgl, NP sēr) > *sai̯ra- > Khot. sīra- “content, happy, satisfied”.Footnote 33 Moreover, Iranian unvoiced fricatives were voiced before *r even at the beginning of a word (e.g. grūs- “to call” < *xrau̯s-, cf. Av. xraosa-).Footnote 34 In word-internal position, Iranian *-axC- > *-aɣC- merged with the outcome of Iranian *-agC- > *-aɣC-.Footnote 35 Examples include: Khot. ttīra- “bitter” < *tai̯ra- < *taɣra- < *taxra- (MP tʾxl, MMP thr, NP talx; Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2004: 2.272); Khot. sāj-: ppp. *sīta- ~ sīya- “to learn” (SGS 132) < *sai̯da- < *saɣda- < *saxta- (EDIV 323); Khot. thīs-, thīś-: ppp. *thīta- ~ thīya “to pull (at, on)” (SGS 42) < *θai̯da- < *θaɣda- < *θaxta- (EDIV 391–392) (cf. also [+ *apa-] pathaṃj-: pathīya- “to restrain”, [+ *us-] usthaṃj-: usthīya- “to take up, pull out”); dajs-: *dīta- ~ *dīya- “to burn” (SGS 43) (cf. padajs-: padīya-; SGS 68) < *dai̯da- < *daɣda- < *daxta- (EDIV 53–4), etc.

If the development *aɣ > *ai̯ took place also before nasals, as is likely, then the following diachronic path can be established for jsīña(a)- “to be killed”: IIr. *ǰaghn- > Ir. *ǰagn- > *ǰaɣn- > *dzai̯n- (*-ɣ- > *-i̯- [j]) > *dzīn- (monophthongization) → gerundive *dzīn-i̯a- > Khot. jsīña(a)-.Footnote 36 This derivation has the advantage of solving the problem of the missing palatalization because monophthongized *ī is not expected to palatalize a preceding consonant (cf. all the aforementioned examples).

If a new Khotanese verbal stem *jsīn- “to kill” is to be proposed, then the instr.abl.sg. jsīnäna “by killing, from killing” in Z 13.124 may be a derivative of this verb: either we are dealing with a derivative in *-a- (KS 1–13) of the type ārūha- “deportment” (cf. anārūha- “motionless”) ← ārūh- “to move, shake”, or with an inflected infinitive formed from the present stem with -ä (KS 284–94, particularly 285 §§ 46.7.1–2).

The above analysis has an additional advantage, allowing a better understanding of the rare compound jsañaulysa- “killer, murder”, only attested in Z 24.452 pharu narya dāruṇa dukha bīḍä jsañaulysä “many severe woes will the causer of death bear in hell” (Emmerick Reference Emmerick1968a: 409) and in Suv 12.14 (ms. Or) haṃdā[r]ä jsañ[au]lysä dīrāṇu härāṇu pathaṃjākä “whether he is a hired killer (= Skt. caṇḍālo), he is a suppressor of evil things” (Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2004, 1: 239). The first compound member of jsañaulysa- can now be interpreted as Khot. jsaña- “killing, murder”, the actual action noun in *-i̯a- from jsan-, which regularly shows palatalization of the nasal (just like saña- < Ir. *sćand-i̯a-). According to Bailey (Dict. 114), the second member continues an Iranian root u̯arz- “to do, work”.Footnote 37

In conclusion, this article has argued that Khotanese inherited a reduplicated verbal stem IIr. *ǰa-ghn- > Ir. *ǰagn-, which yielded *ǰaɣn- > *jsīn- “to kill, slay” through regular sound change in an earlier stage of the language. Synchronically, this verb survives only in two nominal derivatives: the gerundive jsīña(a)- “to be slain, condemned to death” and the abstract noun jsīna- “killing, slaying”.

Technical abbreviations

- 1/2/3

first, second, third person

- acc.

accusative

- act.

active

- Av.

Avestan

- BSogd.

Buddhist Sogdian

- CSogd.

Christian Sogdian

- f.

feminine

- ger.

gerundive

- Gk.

Greek

- IIr.

(Proto-)Indo-Iranian

- inf.

infinitive

- instr.-abl.

instrumental-ablative

- Ir.

(Proto-)Iranian

- Khot.

Khotanese

- LKhot.

Late Khotanese

- loc.

locative

- m.

masculine

- MMP

Manichaean Middle Persian

- MP

Middle Persian

- MSogd.

Manichaean Sogdian

- nom.

nominative

- NP

New Persian

- OAv.

Old Avestan

- OP

Old Persian

- pass.

passive

- PIE

Proto-Indo-European

- pl.

plural

- ppp.

passive past participle

- prs.

present

- sg.

singular

- Skt.

Sanskrit

- Ved.

Vedic Sanskrit

- YAv.

Young Avestan

Khotanese texts

- JS

Jātakastava, edition and translation by Dresden Reference Dresden1955.

- KV

Karmavibhaṅga, edition and translation by Maggi Reference Maggi1995.

- Rāma

Rāma Story, edition by Bailey (KT 3.65–76) and translation by Bailey Reference Bailey1940.

- Sudh

Sudhanāvadāna, edition and translation by De Chiara Reference De Chiara2013; commentary by De Chiara Reference De Chiara2014.

- Suv

Suvarṇabhāsottamasūtra, edition and translation by Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø2004.

- Z

Book of Zambasta, edition and translation by Emmerick Reference Emmerick1968a.

Bibliographic abbreviations

- Cat.

= Skjærvø Reference Skjærvø and Sims-Williams2002

- Dict.

= Bailey Reference Bailey1979

- EDIV

= Cheung Reference Cheung2007

- EWAia

= Mayrhofer Reference Mayrhofer1992–2001

- KS

= Degener Reference Degener1989

- KT 1–5

= Bailey Reference Bailey1945–1980

- LIV2

= Rix et al. Reference Rix2001

- Prolexis

= Bailey Reference Bailey1967

- SGS

= Emmerick Reference Emmerick1968b

- Studies 1

= Emmerick and Skjærvø Reference Emmerick and Skjærvø1982

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to thank Federico Dragoni, Marco Fattori, and Mauro Maggi for comments on a first draft of this article. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for valuable remarks and suggestions for improvements.

Funding information

This research was supported by the 2022 PRIN project “Non-finite verbal forms in ancient Indo-European languages: diachronic, synchronic and cross-linguistic perspectives” (2022RSTTAZ).