Introduction

In recent years, we have seen far-right insurrectionists trying to storm parliament buildings, intending to subvert the government after their supported politicians lost an election. Examples of such coup attempts include the US January 6th Capitol insurrection and the 2023 Brazilian Congress attack.Footnote 1 What holds these far-right coup attempts together is their anti-democratic behaviour as they deny the legitimacy of the electoral game and attempt to perpetuate the power of their losing president. Given the salience of these autocratization events, their impacts were hardly restricted to the domestic level. An exemplar of such a spillover is the US Capitol insurrection. After the coup attempt occurred, there was uproar worldwide, with reporters framing this event as an assault on democratic institutions (Boone, Taylor, and Gallant Reference Boone, Taylor and Gallant2022). Besides, politicians in various countries expressed concerns about this autocratization event. For instance, former German chancellor Angela Merkel condemned the insurrectionists’ behaviour and expressed her anger (Gehrke Reference Gehrke2021). Similarly, after the Brazilian Congress attack, we noticed another uproar. In this case, US President Joe Biden condemned the Congress attack saying it was an ‘assault on democracy’ (Reuters 2023). Given that the impacts of these far-right coup attempts are not confined to state boundaries, they are highly expected to change citizens’ public opinion in other countries. However, the current literature does not shed much light on this topic.

To fill this gap, this article studies the spillover effect of the US January 6th Capitol insurrection – the modern prototype of far-right coup attempts. I consider this insurrection an autocratization event for it denies the election as the ‘only game in town’ and aims to use violent measures to subvert a free and fair election. I argue that a far-right insurrection abroad can trigger a transnational learning process in other liberal democracies. Specifically, as mainstream actors in these countries frame these events as assaults on democracies, the associations between the far-right and the threat to democracy should increase. Such attribute associations can render the domestic far-right party’s anti-democratic potential more salient, which in turn reduces the expressed support of this party family for two reasons. The first is shaming: when domestic mainstream politicians and media condemn far-right insurrection abroad, citizens will notice the reputational costs of supporting the domestic far-right party abruptly surge. The second is a change in voting calculus: when far-right insurrectionists abroad engage in election subversion, citizens may consider the far-right party is now beyond the range of acceptability.

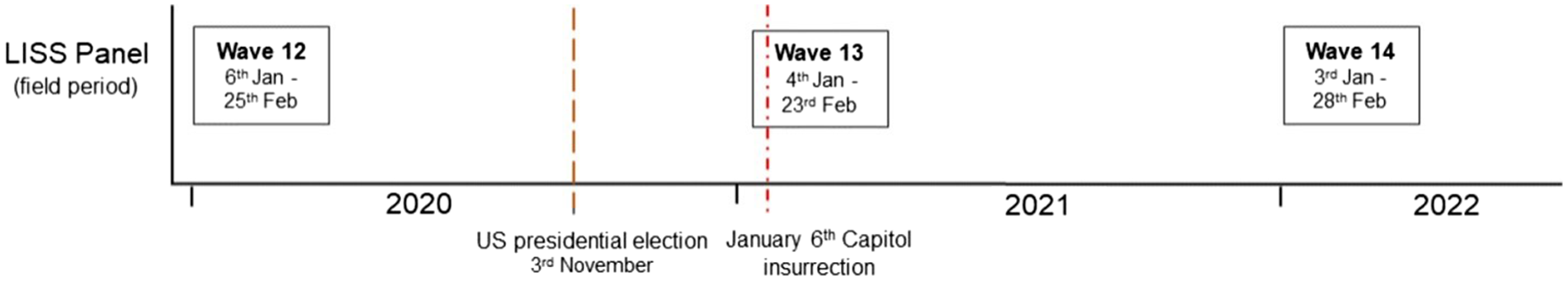

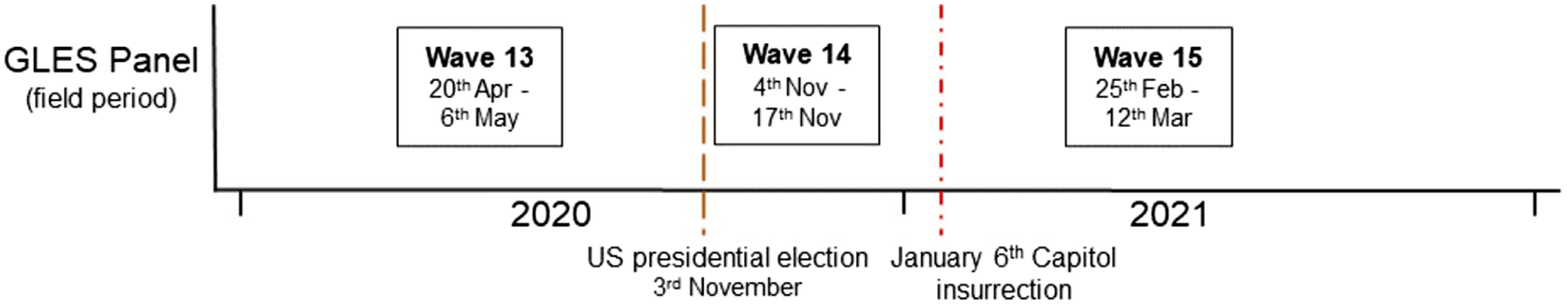

To test whether a far-right insurrection abroad reduces the expressed support for domestic far-right parties, this research analyzes two panel datasets that were fielded amid the Capitol insurrection. In Study 1, I used the LISS (Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences) panel in the Netherlands (N = 2,698), in which one wave was fielded from 4 January to 23 February 2021. Using the unexpected event during survey design (UESD) (Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno, and Hernández Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020), I compare the change in expressed far-right support before the coup attempt and thereafter. In this between-subjects design, the expressed support for a domestic far-right party decreases by around 4.2 percentage points (pp) after the Capitol insurrection. Next, to extend the scope condition, Study 2 uses a within-subjects design and analyzes the GLES (German Longitudinal Election Study) panel (N = 5,653). In this three-wave dataset, one wave was fielded before the US election and one wave thereafter, while the third wave was fielded one-and-a-half months after the Capitol insurrection. Due to this panel data structure, I can identify the spillover effect of a foreign far-right insurrection within the same individual, which is a harder test for my analysis. Additionally, I can disentangle the effect caused by the Capitol insurrection from the titanic effect caused by Trump’s loss, as his defeat could reduce the electoral viability of the far-right party family (Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama Reference Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama2022). Using an individual fixed-effect regression, I similarly find that the expressed support for the domestic far-right party decreases by around 0.68–0.94 pp.

This research speaks to three strands of literature. First, it joins the autocratization literature by studying the spillover effects of a modern prototype of far-right coup attempts, namely, the January 6th Capitol insurrection. Recent studies demonstrate that this far-right coup attempt caused citizens to dissociate from the far-right party family domestically. The consequences of this autocratization event include a substantive decrease in Republican Party identity expression and a reduction in corporate contributions to Republican legislators (Eady, Hjorth, and Dinsen Reference Eady, Hjorth and Dinsen2022; Li and Disalvo Reference Li and Disalvo2023; Loving and Smith Reference Loving and Smith2022). My article echoes these findings and highlights that the effect of a far-right insurrection can occur on a transnational scale. More importantly, I provide a theoretical foundation on why a far-right insurrection abroad can reduce expressed support for the domestic far-right parties.

Second, this article expands on studies of far-right politics. Previous research found that the expressed support for a far-right party depends upon context. To name a few, these contextual factors include social networks (Ammassari Reference Ammassari2022), media coverage (van Spanje and Azrout Reference van Spanje and Azrout2018), mainstream parties’ strategies (Van Spanje and Van Der Brug Reference Van Spanje and Van Der Brug2007), legal prosecutions (Van Spanje and De Vreese Reference Van Spanje and De Vreese2015), and parliamentary representation (Valentim Reference Valentim2021). What is noticeable is that all these factors are at the domestic level. Thus, my article adds to these works by analyzing how a far-right insurrection abroad can change the expressed support for domestic far-right parties.

Third, this article complements the burgeoning research on transnational learning. On the one hand, studies on transnational learning demonstrate that domestic political elites take references from parties abroad (Martini and Walter Reference Martini and Walter2023). Specifically, scholars find that domestic parties emulate the position of incumbent parties abroad (Böhmelt et al. Reference Böhmelt2016) and foreign parties that belong to the same party family (Roumanias, Rori, and Georgiadou Reference Roumanias, Rori and Georgiadou2022; Schleiter et al. Reference Schleiter2021), and there can be a policy backlash effect when populist parties abroad were in government (Adams et al. Reference Adams2022). On the other hand, scholars show that partisans also engage in transnational learning: partisans use their party family’s electoral success/failure abroad to update their vote preferences (Roumanias, Rori, and Georgiadou Reference Roumanias, Rori and Georgiadou2022; Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama Reference Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama2022). My research joins this literature by highlighting that a far-right coup attempt abroad triggers transnational learning among citizens, which in turn changes their expressed support for the domestic far-right parties.

This article is structured as follows. First, I explain why a far-right coup attempt can reduce the expressed support for domestic far-right parties. Next, I use qualitative evidence (i.e. Google Trends and news reports) to substantiate the key assumptions of my theoretical framework. Afterwards, I describe why the cases of the Netherlands and Germany were chosen to study this spillover effect, which is followed by the empirical findings of the two studies. Lastly, I discuss how this article can enrich studies of autocratization, far-right politics, and transnational learning, and point out future research avenues.

Impacts of a Foreign Far-Right Insurrection

It is well documented that far-right parties can pose threats to democracy, especially when these parties are affiliated with social organizations that are prone to extremist violent aggressions.Footnote 2 While far-right parties participate in electoral competitions, they are seldom fully loyal to the basic rules of democracy (Bos and Van der Brug Reference Bos and Van der Brug2010; Carter Reference Carter2013). Using the words of Juan Linz, most far-right parties are ‘semi-loyal’ to democratic systems: they are willing ‘to encourage, tolerate, cover up, treat leniently, excuse, or justify’ political violence and insurrections when these tactics can sustain power and achieve policy goals (Linz Reference Linz1978, 32). Nevertheless, far-right parties are constrained by electoral logic, since a significant proportion of supporters do not intend to overthrow the democratic system (Bos and Van der Brug Reference Bos and Van der Brug2010; van Spanje and Azrout Reference van Spanje and Azrout2018). So, to succeed electorally, most far-right parties need to distance themselves from their anti-democratic extremist flank.

However, when a far-right coup attempt occurs, it can signal that the far-right is unwilling to play by the majoritarian democratic rules and disrespect reciprocity, for it uses violent tactics to subvert a free and fair election. Consequently, this autocratization event can increase the salience of the party family’s anti-democratic potential, whether at the domestic level or a transnational level. Regarding the domestic effect of a far-right insurrection, recent studies show that the US Capitol insurrection reduces the expression of Republican Party identity and decreases corporate contributions to Republican legislators (Eady, Hjorth, and Dinsen Reference Eady, Hjorth and Dinsen2022; Li and Disalvo Reference Li and Disalvo2023; Loving and Smith Reference Loving and Smith2022). In other words, domestically, citizens are less prone to express support for the far-right party once its anti-democratic potential becomes more salient.

I argue this tendency to dissociate from far-right parties can be extended to the transnational level. It is because when a far-right coup attempt occurs abroad, it becomes difficult for domestic citizens to ignore the threats to democracy posed by the far-right parties, as citizens should be more concerned about democracy. Recall what happened after the January 6th Capitol insurrection and after the 2023 Brazilian Congress attack: both domestic mainstream politicians and the media swiftly associated the far-right coup attempt as threatening democratic institutions. At times, the mainstream actors even mentioned that the far-right insurrectionists were affiliated with or sympathetic to fascists and Nazi groupings (Mulraney and Zilber Reference Mulraney and Zilber2021). Certainly, these framings can be seen as an extension of what Moffitt called pariahing, which denotes that the far-right is beyond the pale in democratic systems (Reference Moffitt2022). In my case, the pariahing is a reaction to the far-right coup attempt abroad and occurs on a transnational level. By such attribute associations, the far-right as a whole is portrayed as violence-prone and incompatible with democratic systems.

These attribute associations between far-right and threats to democracy are crucial because they can trigger a transnational learning process. As the far-right abroad engages in a coup attempt, domestic citizens may learn that the domestic far-right parties can be similarly prone to such violent anti-democratic behaviour. Of course, the domestic far-right parties need not remain fully silent, and may even condemn the insurrection abroad to retain their supporters who adhere to the majoritarian institutions of democracy. For instance, after the Capitol insurrection, Nigel Farage (former leader of the UK Independence Party), Matteo Salvini (leader of the Lega Nord), and Marine Le Pen (leader of National Rally) all denounced the insurrection and even expressed the importance of majoritarian democratic institutions in their social media accounts (Al Jazeera, Reference Jazeera2021).Footnote 3 However, because mainstream media hardly reported these messages from far-right politicians, I expect the dissociation messages to barely reach the general population. Hence, the attribute associations between far-right and threats to democracy after the far-right coup attempt abroad should still be a dominant phenomenon. Taken together, I expect that, after a far-right insurrection occurs abroad, citizens are less likely to express support for their domestic far-right parties, as this autocratization event increases the salience of the far-right’s anti-democratic potential.Footnote 4

According to the current literature, two complementary mechanisms underpin this spillover effect from a far-right insurrection: shaming and change in voting calculus. First, the shaming mechanism concerns the social costs of disclosing support for far-right parties after a foreign far-right coup attempt occurs. As demonstrated by the Capitol insurrection, condemnation by domestic mainstream politicians and media swiftly ensued. When domestic actors delegitimize the foreign far-right coup attempt, it can send cues to domestic citizens that far-right parties are associated with election subversion, which threatens democratic institutions. As such, domestic citizens would consider expressing support for domestic far-right parties as less legitimate. This idea of delegitimization is supported by a recent study which shows that democratic behaviour is an important cue for citizens to perceive a party’s legitimacy status (Kölln Reference Kölln2023). As expressing support for far-right parties is more likely to be labelled as anti-democratic and illegitimate, the reputational costs of expressing support for far-right parties should abruptly increase (Harteveld et al. Reference Harteveld2019). Thus, to avoid negative social evaluations, citizens hide their support for these socially undesirable parties in public, despite their support in private (Blinder, Ford, and Ivarsflaten Reference Blinder, Ford and Ivarsflaten2013).

The second mechanism is the change in voting calculus after citizens are exposed to a far-right coup attempt abroad. This mechanism concerns the conflict of considerations when citizens express support for the domestic far-right parties. Previous studies noted that far-right supporters are pulled between two considerations. While they are attracted by the party’s nativist programme, most of them also subscribe to democratic systems, particularly the idea of a majority government and peaceful transfer of power (Bos and Van der Brug Reference Bos and Van der Brug2010; van Spanje and Azrout Reference van Spanje and Azrout2018). At ordinary times, when these voters express support for far-right parties, they put nativist considerations at the forefront, as the far-right parties’ anti-democratic potential is not salient. However, when a far-right insurrection occurs abroad, the anti-democratic potential of their domestic far-right parties should come into consideration because of the attribute associations by mainstream actors. Since the act of insurrection signals a disrespect for free and fair elections, some far-right supporters may be less willing to accept this party family. This mechanism can draw support from the literature on tolerance and political violence, which suggests citizens consider a political group less acceptable when this group engages in violent behaviour (Petersen et al. Reference Petersen2011; Pickard, Efthyvoulou, and Bove Reference Pickard, Efthyvoulou and Bove2023; Simpson, Willer, and Feinberg Reference Simpson, Willer and Feinberg2018). That means the change in acceptability is grounded on the far-right’s unwillingness to play by the majoritarian democratic rules and disrespect for reciprocity. So, if citizens perceive the domestic far-right parties as beyond the zone of acceptability due to the far-right insurrection abroad, the expressed support for far-right parties should decrease.

Key Assumptions of the Theoretical Framework

The above theoretical framework suggests a far-right coup attempt abroad can trigger a transnational learning process: as the far-right’s anti-democratic potential becomes more salient, citizens are less prone to express support for the domestic far-right parties. Accordingly, two mechanisms may drive this effect: shaming and change in voting calculus. Yet, it is necessary to point out that this framework rests on three main assumptions. First, citizens in other liberal democracies should be more concerned about democracy after a far-right insurrection. Second, due to the framings by mainstream actors, there should be an association between the concern for democracy and the far-right. Third, there should not be any confounding domestic events that can change the expressed support for the domestic far-right parties. This section uses qualitative evidence to substantiate these assumptions.

Since the US Capitol insurrection was a highly unexpected event, the first two assumptions can hardly be verified at the individual level, especially when conventional surveys seldom ask the corresponding questions. To deal with this challenge, I turned to Google Trends data in nine Western European countries from 25 December 2020 to 25 January 2021. Regarding the first assumption, I explore the trend of the topic of ‘coup’ because both experimental and qualitative studies on coups suggest this political label signals a threat to democratic rules (Grewal and Kinney Reference Grewal and Kinney2022; Yukawa, Hidaka, and Kushima Reference Yukawa, Hidaka and Kushima2020). As seen from the red line of Fig. 1, there is a clear spike right after the Capitol insurrection. Complementarily, I look at the trend of the search term ‘democracy’. From the blue line of Fig. 1, one can easily notice a surge after the Capitol insurrection in each country.Footnote 5 Taken together, the trend of ‘coup’ and that of ‘democracy’ indicate citizens in liberal democracies should have been aware of this anti-democratic behaviour, and democracy is a trending concern after the far-right coup attempt.

Figure 1. Google Trends: Search for democracy and far-right politics in Western Europe.

Note: The search period is from 25 December 2020 to 25 January 2021. The Y-axis is the count of the search that is normalized to a 0–100 range. The red solid line is the search for the topic of ‘Coup d’état’. (see Table A.1 for this topic’s related queries).

Talking about the second assumption, I look at the trend related to the search for the topic of ‘far-right politics’ (purple dotted lines). By correlating this trend with the ‘democracy’ trend, I find that the average correlation across these countries is 0.386. The lowest correlation is in Italy at 0.159, while the highest is in Portugal at 0.621. These correlations suggest that the concern for democracy is associated with the far-right. Still, two caveats shall be made in using Google Trends to back up such an association. For one, this piece of evidence is at the aggregate level and indirect. For another, Google Trends cannot distinguish between how mainstream parties/elites framed the Capitol insurrection and the framings adopted by far-right parties/elites. The latter limitation is crucial because some domestic far-right politicians may dissociate themselves from the far-right insurrection abroad in an attempt to assure their supporters that they are not threats to democracy. To handle this limitation, I turn to the mainstream news outlets in the corresponding countries of this research; namely, the Netherlands Public Television (NOS) and the Tagesschau for Germany. In line with the theoretical argument, these mainstream outlets did not report how domestic far-right parties reacted to the Capitol insurrection. Rather, the news reports were dominated by domestic mainstream politicians’ condemnation (see Appendix Section A.2 for details). Therefore, this qualitative evidence from news reports, alongside the Google Trends correlations, should support that the attribute associations framed by mainstream actors were dominant.

Last, regarding the possibility of domestic confounding events, I similarly turn to the mainstream news outlets in the Netherlands and Germany. For the Netherlands, I scraped all news headlines from NOS during the field period of the dataset (from 4 January 2021 to 23 February 2021). Using this qualitative evidence, I cannot find any domestic events that could cause a significant change in expressed support for far-right parties (see Appendix Section A.3 for details). Similarly, for Germany, I scraped all headlines from Tagesschau that were reported from 18 November 2020 to 24 February 2021. Here, I find one domestic event that may affect the expressed support for the far-right party. This event is the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) leadership contest on 15 January 2021. In this intra-party contest, Armin Laschet was elected as party leader with 52.79 per cent of delegate votes. However, theoretically, it is unclear why this leadership contest could cause a drop in expressed support for the far-right party. It is because Armin Laschet was portrayed as the successor of Merkel (Carrel and Käckenhoff Reference Carrel and Käckenhoff2020), whom AfD voters heavily dislike (Chan Reference Chan2022). Thus, this domestic event should speak against the theoretical expectation of the spillover effect.

Case Selection and Empirical Setting

To study whether a foreign far-right insurrection decreases the expressed support for domestic far-right parties, this research focuses on two liberal democracies – the Netherlands and Germany. There are two reasons for analyzing these two liberal democracies. First, I can test whether the spillover effect is generalizable. As these two countries have different electoral systems and their far-right parties are of different electoral strengths,Footnote 6 I can analyze if the spillover effect of the Capitol insurrection is replicable in various political contexts. Second, the effects being estimated in these two countries are likely to represent a lower bound of the spillover effect. It is because the domestic far-right parties tried to dissociate from the Capitol insurrection, which is in line with the theoretical framework.Footnote 7 So, suppose these dissociation strategies are effective in retaining supporters, the decrease in expressed support for far-right parties would have been larger had they not adopted such strategies.

In the following, I describe Study 1 (Netherlands) and Study 2 (Germany), which employ a between-subjects design and a within-subjects design respectively.

Study 1

Data and Research Design

The first study uses the LISS panel, which is a probability sample of households drawn from the population register by Statistics Netherlands. The interviews are self-administered and conducted via the Internet. One key characteristic of this dataset is that Wave 13 was fielded right before and after the Capitol insurrection (that is, 4 January 2021–23 February 2021). Assuming the interview’s day is random with respect to the event, I can identify the spillover effect of the far-right insurrection using UESD (Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno, and Hernández Reference Muñoz, Falcó-Gimeno and Hernández2020). In this setting, those surveyed before the Capitol insurrection are the control group (N = 982), while those surveyed after the event are the treatment group (N = 1,716). Respondents who were surveyed on 6 January were excluded from the analysis. The main analysis uses entropy reweighting to create a balanced sample (Hainmueller and Xu Reference Hainmueller and Xu2013), as the control group and the treatment group are slightly imbalanced in some socio-demographic covariates (see Appendix Table B.1 for survey questions and variable operationalizations).Footnote 8

The outcome is the expressed support for a far-right party. The LISS survey asks respondents the vote preference question: ‘If parliamentary elections were held today, for which party would you vote?’ The dependent variable is coded as 1 if they answer they vote for a far-right party – PVV (Wilders Freedom Party) or Forum voor Democratie (Party for Democracy) (de Jonge Reference de Jonge2021). If respondents support other parties, the variable will be coded as 0. If respondents (i) choose abstention, (ii) say they cast a blank vote, (iii) answer ‘I don’t know’, or (iv) ‘I prefer not to say’, the variable is coded as missing in the main analysis. In the robustness checks, I include (i)–(iv) and code these answers 0. The substantive interpretation remains the same. In short, Study 1 is a between-subjects design: I compare the change in expressed support for a domestic far-right party before the Capitol insurrection and thereafter.

Moreover, because the LISS dataset is a panel, the same respondents are asked to express their vote preference annually in different waves, as shown in Fig. 2. Due to this panel data structure, there are several strengths that most research using UESD cannot find. First, I use its previous wave (Wave 12) to check whether the parallel trend assumption is fulfilled. If the assumption is satisfied, the likelihood of expressing support for a far-right party should be similar between the control group and the treatment group before the Capitol insurrection occurred (Wave 12). Second, I can analyze the subsequent wave (Wave 14), which was collected a year after the Capitol insurrection, as a manipulation check. In this manipulation check, the probability of voting for a far-right party should once again be similar between the control group and the treatment group since the control group in Wave 13 is now exposed to the Capitol insurrection. Third, I can use the subsequent wave (Wave 14) to ascertain the persistence of the effect. If the effect of the far-right insurrection is persistent, the likelihood of supporting a far-right party should not recover to the pre-treatment level among the treatment group in Wave 13. To the best of my knowledge, barely any research that uses UESD has conducted these tests jointly.

Figure 2. Data structure of the LISS (Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences) panel in the Netherlands.

Results

Figure 3 illustrates the expressed support for a far-right party before and after the Capitol insurrection in the Netherlands (For the regression result, see Model 1 in Table B.2). Panel (a) shows the probability of voting for a far-right party among the control group and the treatment group. Panel (b) illustrates the coefficient estimate of the treatment (that is the Capitol insurrection). In line with the theoretical framework, citizens are less likely to express support for a far-right party by around 4.2 pp (p = 0.013) after a foreign far-right insurrection.Footnote 9 Though an expressed preference may not translate into voting behaviour (Valentim Reference Valentim2024), this drop could mean the far-right parties losing around 6–7 representatives within the 150-seat House of Representatives in public polling.

Figure 3. Probability of voting for a far-right party and coefficient estimates.

Note: The dependent variable is a binary outcome, which is coded as 1 if the respondent expresses support for a far-right party (that is Wilders Freedom Party or Party for Democracy) and 0 if he/she expresses support for other parties. In panel (a), the predicted probabilities of voting for a far-right party are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Panel (b) reports the estimates of the Capitol insurrection (see Table B.2); thin and thick bars indicate 90 and 95 per cent confidence intervals respectively. All models are entropy-weighted using age, gender, civil status, education level, income, urban character of the place of residence, and respondent’s origin.

As mentioned, the LISS panel has a data structure that is exceptionally rare in UESD research: it asked the same respondents to express their vote preference annually over different waves. This data structure allows me to conduct several tests to see if the above findings are robust. First, I use Wave 12 which was fielded a year before the Capitol insurrection, to check for the parallel trend assumption. Figure 4 illustrates this assumption is met, since the likelihood of voting for a far-right party is statistically indistinguishable between the two groups in the pre-treatment period (p = 0.656) (For the regression result, see Table B.3). Second, I use the subsequent wave (Wave 14) to conduct a manipulation check, for the control group has already been exposed to the treatment (i.e. Capitol insurrection) in 2022. Figure 4 demonstrates that this manipulation check was passed as well since the predicted probabilities of expressing support for far-right parties are once again similar among the control group and the treatment group (p = 0.310). Third, I ascertain whether the spillover effect is persistent by focusing on the treatment group throughout Wave 13 to Wave 14. The dark purple dotted line indicates that the treatment group’s probability of voting for a far-right party does not recover to the pre-treatment level and remains stable. In other words, the spillover effect of the Capitol insurrection is persistent for at least a year. Overall, these tests consolidate the findings that a far-right insurrection abroad decreases the expressed support for domestic far-right parties.

Figure 4. Comparing the predicted probability of expressing support for a far-right party across waves (Control group vs. Treatment group in Wave 13).

Note: The dependent variable is a binary outcome, which is coded as 1 if the respondent expresses support for a far-right party (that is Wilders Freedom Party or Party for Democracy) and 0 if he/she expresses support for other parties. The predicted probabilities of voting for a far-right party are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals (see Table B.3 for regression table). The model is entropy-weighted using age, gender, civil status, education level, income, urban character of the place of residence, and respondent’s origin. The model is estimated based on respondents who participated in all three waves.

In the appendix, I conduct a series of robustness checks to strengthen the findings of the spillover effect. First, I rerun the analysis using other model specifications. They include a model without entropy weight, an entropy-weighted model that only uses imbalanced covariates (Figs B.3–B.4 and Table B.4), and a binary logit model (Figure B.5 and Table B.5). The spillover effect holds across all models. Second, I conduct placebo tests by changing the dependent variable to the expressed support for (a) far-left parties and (b) incumbent parties. For these two placebo outcomes, I cannot find any effects (Figure B.6–B.7 and Table B.6). Third, I code respondents as 0 rather than missing if they (i) choose abstention, (ii) say they cast a blank vote, (iii) answer ‘I don’t know’, or (iv) ‘I prefer not to say’ in the expressed vote preference question. The spillover effect still holds (Figure B.8 and Table B.7); so are the parallel trend assumption, the manipulation check, and the effect persistence (Figure B.9 and Table B.8). Lastly, I rerun the model by using the LISS dataset collected in 2018.Footnote 10 The motivation of this pseudo-threshold model is to eliminate the possibility that far-right supporters are prone to answer surveys earlier than other citizens. I cannot find this possibility (Figure B.10 and Table B.9).Footnote 11

Study 2

Data and Research Design

One may challenge Study 1 by arguing that it relies on the case of the Netherlands, which has high electoral volatility due to its proportional system (de Vries and Hobolt Reference de Vries and Hobolt2020, 245–247). Also, it uses a between-subjects design in which the socio-demographic covariates are slightly imbalanced (see footnote 8). To address these critiques, Study 2 employs a within-subjects design to identify the spillover effect of a far-right insurrection and analyzes whether the spillover extends to another scope condition – Germany, which has lower electoral volatility. The dataset is the GLES Wave 13 to Wave 15 (2021) with its data structure shown in Fig. 5. The respondents were recruited from an opt-in online panel, and the survey mode used in these waves was computer-assisted web interviews. In total, 5,653 respondents participated in Wave 13, with the retention rate in Wave 15 at 85.2 per cent. In terms of the data collection period, Wave 13 was fielded around six months before the 2020 US presidential election while Wave 14 was fielded right after the election (4 November to 17 November 2020), which was two months before the Capitol insurrection.Footnote 12 Wave 15 was fielded one-and-a-half months after the insurrection (25 February to 12 March 2021).

Figure 5. The data structure of the GLES (German Longitudinal Election Study).

To reiterate, using a within-subjects design to identify the spillover effect of a far-right insurrection should be a harder test than Study 1 because it identifies the change in expressed far-right support within the same individual. Here, respondents who are surveyed before the Capitol insurrection are the control group, whereas those who are surveyed afterwards are the treatment group. Importantly, this design allows me to disentangle the titanic effect caused by Trump’s loss (Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama Reference Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama2022) from the spillover effect of the Capitol insurrection. According to Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama (Reference Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama2022), the electoral defeat of a far-right party abroad can reduce expressed support for domestic far-right parties because of a drop in the party family’s electoral viability. Therefore, this dataset can distinguish the effect of these two events (Trump’s electoral loss vs. Capitol insurrection).

I use an individual fixed-effects model to estimate the effect of the far-right insurrection, which controls for unobserved heterogeneity. Since Germany has a mixed-member electoral system, there are two dependent variables: (i) party vote for a far-right party and (ii) candidate vote for a far-right politician. The far-right parties include Alternative for Germany (AfD), Die Rechte, NPD (National Democratic Party), and the REP (Republikaner) (Goerres, Spies, and Kumlin Reference Goerres, Spies and Kumlin2018; Schulte-Cloos Reference Schulte-Cloos2022). The GLES survey asks respondents, ‘You have two votes in the federal election. The first vote is for a candidate in your local constituency, the second vote is for a party. How will you mark your ballot?’ The dependent variable is coded as 1 if respondents answer they vote for a far-right party. If respondents answer supporting other parties, the variable is coded as 0. If respondents (i) claim they do not intend to vote, (ii) answer don’t know, or (iii) provide no answer, the variable is coded as missing in the main analysis (see Appendix Table C.1 for survey questions and coding scheme). Again, in the robustness check, I include (i)–(iii) and code these answers as 0.

Results

Figure 6 panel (a) shows the probability of voting for the far-right in the party vote in three periods: (i) before the US presidential election, (ii) after the election, and (iii) after the Capitol insurrection. Panel (b) illustrates the marginal effect of Trump’s electoral loss and that of the Capitol insurrection when compared to the pre-US presidential election period (For full regression results, see Table C.2). First, I cannot find a statistically significant titanic effect caused by Trump’s loss, although the estimate is in the negative direction (p = 0.188). Contrarily, the effect of the Capitol insurrection is obvious. Citizens are less likely to express support for a far-right party by around 1.11 pp compared to the pre-election wave (that is Wave 13) (p = 0.005). Even when compared to the post-election wave (Wave 14), citizens are still less prone to support a far-right party by around 0.68 pp, and the effect is marginally significant (p = 0.067). Since Study 2 is a within-subjects design, the effect’s magnitude is expected to be smaller than that of Study 1. However, because a within-subject design controls for unobserved heterogeneity, this finding can give us more confidence that the US far-right coup attempt reduces the expressed support for the domestic far-right party. In substantive terms, this effect can mean the far-right losing around five seats (out of 709 seats) in public polling,Footnote 13 even though one cannot be certain whether these supporters switch parties in the ballot box (Valentim Reference Valentim2024).

Figure 6. GLES dataset: Probability of voting for the far-right party or candidate and the coefficient estimates.

Note: The dependent variable is a binary outcome, which is coded as 1 if the respondent expresses support for a far-right party (that is AfD, Die Rechte, NPD, and the REP) and 0 if he/she expresses support for other parties. In panels (a) and (c), the predicted probabilities of voting for a far-right party are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Panels (b) and (d) report the estimates of the Capitol insurrection (see Table C.2); thin and thick bars indicate 90 and 95 per cent confidence intervals respectively.

Next, I look at whether the Capitol insurrection would similarly change the expressed support for the far-right candidate. The candidate vote should be a more stringent test for the spillover effect than the party vote because the constituency seats were dominated by two mainstream parties (that is the Christian Union parties (CDU/CSU) and the Social Democratic Party) before the 2021 federal election.Footnote 14 As such, those who use the candidate vote to support a far-right politician are likely adamant supporters, and it should be difficult for them to withdraw their expressed support. Still, panels (c) and (d) of Fig. 6 show that the result is similar to that of the party vote. Again, there is no titanic effect caused by Trump’s loss (p = 0.485). By contrast, we can clearly observe an effect after the Capitol insurrection: citizens are less likely to express support for a far-right candidate by around 1.18 pp when compared to the pre-election wave (p = 0.001), and 0.94 pp when compared to the post-election wave (p = 0.005).

As robustness checks, I first code respondents as 0 rather than missing if they (i) claim they do not intend to vote, (ii) answer don’t know, or (iii) provide no answer (Figure C.1 and Table C.3). Interestingly, I find a titanic effect in their party vote at a magnitude of 0.58 pp that is marginally significant (p = 0.067). In other words, far-right supporters may be more likely to avoid answering the vote preference question after Trump’s loss rather than switching parties. Nevertheless, the effect of the Capitol insurrection is still present in both the party vote and the candidate vote.

Second, I check whether there is differential attrition among far-right supporters and non-far-right supporters. Specifically, I look at whether the drop-out rates from Wave 14 to Wave 15 are significantly different between far-right supporters and non-far-right supporters. Here, I use their expressed vote preference in Wave 13 (before the US presidential election and the Capitol insurrection) to identify two groups, and cannot find any differential attrition (Table C.4). Thus, the spillover effect is unlikely to be confounded by differential attrition.

Third, as placebo tests, I change the dependent variables to expressed support for the Left Party (that is Linke) and the Green Party and rerun the individual fixed-effects model (Table C.5). According to the theoretical framework, a far-right insurrection abroad should not cause a drop in support for left-wing parties. Assuringly, I cannot find a decrease in the expressed support for these two left-wing parties (Figure C.2 and Figure C.3).Footnote 15

Conclusion

The Capitol insurrection marked a watershed of democratic backsliding not simply in the US, but also worldwide. Since then, scholars have started studying its domestic impacts, which found that the Republican Party’s supporters dissociated from the party after this coup attempt (Eady, Hjorth, and Dinsen Reference Eady, Hjorth and Dinsen2022; Li and Disalvo Reference Li and Disalvo2023; Loving and Smith Reference Loving and Smith2022). But despite the global coverage this autocratization event received, very little is known about whether this far-right insurrection causes spillover. My article fills this gap by studying how citizens in other liberal democracies react to this prototype of the far-right coup attempt. I argue that a far-right insurrection abroad can increase the salience of the party family’s anti-democratic potential as the attribute associations between far-right and threats to democracy become more prominent. Consequently, due to shaming and a change in voting calculus, the domestic far-right parties receive less expressed support. To demonstrate this transnational learning process, I use two datasets collected amid the Capitol insurrection. The results demonstrate that the far-right parties in the Netherlands and Germany both experienced a decrease in expressed support after the Capitol insurrection.

These findings bridge three disconnected strands of literature, namely autocratization, far-right, and transnational learning. First, regarding studies on autocratization, scholars often ignore how one country’s autocratization event causes spillover in other countries. Studies that use macro-level indicators tend to illustrate how different countries experience autocratization contemporaneously instead of their causal interaction (Boese et al. Reference Boese2021; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019). Conversely, for studies that use micro-level survey data to identify why citizens condone authoritarian behaviour, they presume each country is independent (Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen2022; Krishnarajan Reference Krishnarajan2022), thus neglecting a foreign autocratization event’s impact. My research addresses this blind spot by demonstrating how an autocratization event initiated by the far-right causes transnational learning, which in turn changes public opinion in other countries.

Second, this article highlights that the literature on the far-right should consider the transnational learning process of an autocratization event more seriously. Though previous works have documented that the expression of far-right support is contextual-dependent, the factors being considered are often at the domestic level (Ammassari Reference Ammassari2022; Valentim Reference Valentim2021; van Spanje and Azrout Reference van Spanje and Azrout2018; Van Spanje and De Vreese Reference Van Spanje and De Vreese2015). As this article finds that a far-right coup attempt abroad can reduce the expressed support for domestic far-right parties, future works can explore how domestic far-right support is affected by other transnational factors.

Third, this research bears implications for how we think of transnational learning. The burgeoning research on transnational learning demonstrates that political elites and partisans use their party family’s electoral success/failure abroad as information. Through this information, political elites would adjust their positions by taking references from foreign parties (Adams et al. Reference Adams2022; Böhmelt et al. Reference Böhmelt2016; Martini and Walter Reference Martini and Walter2023; Schleiter et al. Reference Schleiter2021) while partisans update their vote preferences (Roumanias, Rori, and Georgiadou Reference Roumanias, Rori and Georgiadou2022; Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama Reference Turnbull-Dugarte and Rama2022). Noticeably, the information of the updating process is the electoral result and incumbency of a foreign party. My research broadens this literature by highlighting that a far-right insurrection abroad can similarly serve as information for transnational learning. Thus, more research should follow up on how political elites and partisans learn from far-right coup attempts abroad.

Nevertheless, there are several limitations that only future studies can address. The first two limitations concern the scope condition. First, this research merely studies the spillover of a modern prototype of far-right insurrections. Thus, one extension is to focus on another recent far-right insurrection – the 2023 Brazilian Congress attack. Will this far-right insurrection in an unconsolidated democracy likewise lead to spillover in other countries? More importantly, the US Capitol insurrection and the Brazilian Congress attack are all affiliated with the far-right camp. Yet, the far-left camp engaged in insurrections as well. One example of such autocratization events is the 1992 Venezuelan coup attempt led by Hugo Chávez. According to the literature on far-left autocratization (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2016; Kronick, Plunkett, and Rodriguez Reference Kronick, Plunkett and Rodriguez2023), the relationship between far-left and threats to democracy is more ambiguous: because the far-left authoritarians challenged the exclusiveness of parliamentary democracy by imposing neoliberal reforms, a far-left coup attempt can be justified in the name of ‘deepening democracy’ by promoting citizens’ participation. As such, the association between the far-left and threats to democracy may be less obvious than those induced by a far-right coup attempt. Nevertheless, whether a far-left coup attempt abroad would likewise cause spillover effects is an exciting topic to explore.

Second, the receiver countries analyzed are Western liberal democracies. This setting raises questions about whether similar spillover effects would arise in non-Western countries. For one, Western European countries generally have a resilient democratic system. Crucially, the mainstream politicians and media in these liberal democracies condemned Trump and expressed concern after the Capitol insurrection (Gehrke Reference Gehrke2021) (see also Appendix Section A.2). These reactions certainly matter in the attribute associations between far-right and threats to democracy. For another, Western European countries have a deep-seated tradition of using left/right. This political communication tradition is important in understanding the spillover effect. It is because the transnational learning process presumes that, after a far-right insurrection abroad occurred, citizens would perceive the far-right as a threat to democratic institutions. Thus, it is a moot point whether the effect can be fully generalizable in countries where the connotations of left/right are less obvious (Tavits and Letki Reference Tavits and Letki2009). In the Appendix, I replicate the Google Trends in Eastern European countries (Figure A.1): the spikes in the topic of coups and the search for democracy are much less salient and the correlation between the trends of democracy and far-right politics is much weaker than that in Western Europe (ρ = 0.051). Therefore, more investigations are needed to test whether and why the effect of a far-right coup attempt is muted in non-Western countries.

In terms of empirical evidence, three questions are unanswered. One empirical question concerns the association between the concern for democracy and the far-right: I establish this using Google Trends and other mainstream news sources. Such aggregate-level evidence cannot directly tap into whether an individual is more likely to consider the domestic far-right party as threatening the democratic system after the Capitol insurrection. Previous research on the far-right has asked respondents to what extent a party respects democratic rules (Bos and Van der Brug Reference Bos and Van der Brug2010; van Spanje and Azrout Reference van Spanje and Azrout2018). This can be one direction that studies whether citizens consider the domestic far-right as posing threats to democracy at the micro-level.

Another empirical question is about the persistence of this spillover effect. In the case of the Netherlands, I find that the drop in expressed support for domestic far-right parties could persist for at least a year. However, from several recent elections in liberal democracies, we see Giorgia Meloni in Italy was elected as the premier, Javier Milei in Argentina obtained the presidency, and PVV in the Netherlands became the largest party in the parliament. These electoral successes suggest the US coup attempt did not seem to bring a lasting shift in the far-right’s vote shares inside and outside Europe. Therefore, one key empirical issue is when and how domestic political competition can attenuate the effect of the far-right insurrection abroad. Relatedly, more works are needed to investigate whether the condemnation of these autocratization events abroad is still effective in reducing citizens’ expressed support for the domestic far-right.

Last, my theoretical framework argues that two mechanisms can explain why a far-right insurrection abroad decreases the expressed support for domestic far-right parties. Yet, this article does not fully disentangle the two. To do so, one needs to use behavioural measures in addition to the expressed vote preference. For instance, the shaming mechanism would expect citizens to still support the domestic far-right parties in private settings such as voting in the ballot box or donating to party organizations. According to the shaming mechanism, these supporters shy away from expressing support only because of a change in the social environment. Put differently, these far-right supporters are falsifying their preferences in public and this drop in expressed support may not fully translate into behaviour (Valentim Reference Valentim2024). Contrarily, the change in the voting calculus mechanism would expect more consistency between the expressed political preferences and such private political behaviour. Therefore, future research can study whether this decrease in expressed support would give rise to a change in political behaviour. Nevertheless, understanding the change in expressed support for the far-right party is important because public polling does affect politicians’ speech (Hager and Hilbig Reference Hager and Hilbig2020) and citizens’ decision-making processes (Roy, Singh, and Fournier Reference Roy, Singh and Fournier2021).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000413.

Data availability statement

Replication Data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/X6AVRZ.

Acknowledgements

I thank Brian Boyle, Tania Gosselin, Allison Harell, Maarja Luhiste, Matt Polacko, Sebastian Popa, Dimitris Skleparis, Joost van Spanje, Laura B. Stephenson and Anthony Zito for their valuable feedback. An earlier version of this research was presented at the 2023 Canadian Methodology Conference (MapleMeth), the 2023 Elections, Public Opinions & Parties (EPOP) Annual Conference at the University of Southampton, the University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM), and Newcastle University. I am grateful to the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments.

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

None.

Declaration

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.