The ideological differences between political parties – what is commonly understood as party polarization (Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Sartori Reference Sartori, La Palombara and Weiner1966) – clarify the supply side of elections and signal to citizens that their vote matters (Downs Reference Downs1957; Ezrow and Xezonakis Reference Ezrow and Xezonakis2011; Hobolt and Hoerner Reference Hobolt and Hoerner2020). Party polarization has a formative and galvanizing effect on voters, increasing the likelihood that they develop coherent ideological attitudes and partisan attachments (Adams, De Vries, and Leiter Reference Adams, De Vries and Leiter2012a; Dassonneville, Fournier, and Somer-Topcu Reference Dassonneville, Fournier and Somer-Topcu2022; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010; Lupu Reference Lupu2015). However, too much polarization can deepen political division and impede democratic compromise and stability (for example, Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Gidron, Adams, and Horne Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Hobolt, Leeper, and Tilley Reference Hobolt, Leeper and Tilley2021; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; McCoy, Rahman, and Somer Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; Wagner Reference Wagner2021).

To date, much of the literature conceives of ideological polarization as a one-dimensional phenomenon with policy differences between parties neatly aligning along a general left-right axis. We believe, however, that one-dimensional polarization is unsuited to characterize European politics, as the scholarly consensus now postulates (at least) two dimensions to adequately capture political conflict among parties (Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012; Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). In addition to an economic dimension, a cultural divide has materialized that, in the broadest sense, pits those who are set to gain from a transnational world against those who resist a weakening of national culture and traditional values (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Inglehart Reference Inglehart1990). While the two dimensions may be correlated, it is not a foregone conclusion that they collapse into one.

If one takes the multidimensional nature of political conflict in Europe seriously – as we believe one should – this has important theoretical, methodological, and empirical implications for the study of party polarization. Theoretically, the multiplicity of ideological oppositions raises the question of whether the dimensions reinforce or crosscut each other, which ties discussions of polarization to age-old discussions around pluralism. Limiting the discussion of polarization to a single dimension is tantamount to embracing dualism, or the juxtaposition of two ideological poles (Sartori Reference Sartori, La Palombara and Weiner1966), which inadequately describes current European party systems.

Methodologically, multidimensionality requires a different measurement strategy for polarization. The dominant approach in the literature is to measure polarization through the variance in party positions (Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Sigelman and Yough Reference Sigelman and Yough1978; Taylor and Herman Reference Taylor and Herman1971). Defining the variance in terms of a single dimension presupposes that various ideological conflict lines are perfectly correlated or, one could also say, mutually reinforcing. As a general rule, this is not true in contemporary European politics. Yet, simply adding the economic and cultural variances is not the answer either, since that presumes dimensional orthogonality – the lack of any correlation along conflict lines – or perfect ‘cross-cuttingness.’ We require a more flexible measurement strategy, which we develop here.

Finally, from an empirical perspective, polarization along multiple dimensions may carry very different consequences. If conflicts along different divides are cross-cutting, a one-dimensional measure will, by definition, be unable to capture the ideological differences between parties. This may lead us to misreport polarization and its consequences for key democratic outcomes, such as representation and voter engagement (including turnout, satisfaction with democracy, and partisanship). Thus, we need to consider the variance as well as the correlation of ideological conflict to evaluate its full ramifications.

In this study, we explore polarization in a multidimensional political space, covering both Eastern and Western Europe between 1999 and 2019. We propose an approach that takes into account the effective dimensionality of ideological conflict, ranging from fully mutually reinforcing to fully cross-cutting divides, and any situation in between. Here, our analyses are based on two-dimensional party position estimates derived from the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES; Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022), which includes convenient and validated (Steenbergen and Marks Reference Steenbergen and Marks2007) measures of different ideological dimensions that have been shown to correlate highly with voter perceptions of parties (Dalton and McAllister Reference Dalton and McAllister2015). Our approach is general, however, and can be applied to any source of party placement data (for example, party manifestos) and, crucially, to more than two dimensions.

We make four important contributions. First, we advance a theoretical understanding of polarization and its consequences that is more appropriate for the multidimensional nature of party conflict in Europe. Our argument centres on the relationship between different ideological divides and applies to any setting with two or more dimensions. In these settings, we build a bridge between two hitherto distinctive approaches to understanding polarization: constraint v. variation (Baldassari and Gelman Reference Baldassari and Gelman2008; Dalton Reference Dalton2008). Second, as a conceptual contribution, we introduce the effective number of dimensions, which is distinct from potential dimensionality. Third, we develop a measure that captures party polarization along multiple ideological divides. Finally, we show empirically how this measure better accounts for one of the democratic outcomes reliably associated with party polarization, to wit mass partisanship (for example, Adams, Ezrow, and Leiter Reference Adams, Ezrow and Leiter2012b; Baldassari and Gelman Reference Baldassari and Gelman2008; Dassonneville and Çakır Reference Dassonneville and Çakır2021; Lupu Reference Lupu2015).

Our paper is organized as follows. Using case studies from Portugal and the Netherlands, the next section argues why it is important to take observed multidimensionality seriously in the study of party polarization. We follow this by introducing the concept of effective dimensionality. The key point here is to distinguish between potential and effective dimensions to identify situations where a one-dimensional representation fits and those where it does not. We then develop a new measure of party polarization that combines effective dimensionality and party positional variance, and provide a validation of its conceptualization and measurement. Finally, we demonstrate how the reliance on multidimensional polarization is better capable of predicting mass partisanship than customary one-dimensional approaches. We conclude by discussing the normative implications of our work and its possible extensions for various subfields of political science.

Why Multidimensionality Matters for Polarization

Sartori (Reference Sartori, La Palombara and Weiner1966, 138) uses the term ‘polarized’ as an indicator of distance. We follow suit and argue that a party system is more polarized when parties take more distinctive positions, that is when there is greater variance. This spatially motivated idea of polarization is very broad, as distance may pertain to any political issue. It is well-known, however, that both political parties and voters stand to gain from bundling issues into political ideologies (canonical citations include Downs Reference Downs1957; Hinich and Munger Reference Hinich and Munger1994). A typical assumption in the literature is that a single left-right dimension suffices to understand how parties behave. This dimension is general, in that it encompasses most if not all of the positional differences across parties.

As a starting point, a one-dimensional characterization of party polarization is certainly reasonable, if only to pay heed to Occam’s razor. It certainly has yielded important insights about the United States, where it is commonplace to assume a single ideological axis (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964; Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal1997). The European context, too, contains examples where a one-dimensional approach at times may seem appropriate. In general, however, the situation in Europe is more complex and to insist on a one-dimensional characterization of party polarization may mask the true nature of the phenomenon and its consequences.

What is different about Europe? It is commonly understood that, since the 1970s, party conflict has generally played out multidimensionally (Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010). The first dimension concerns economic matters and may be viewed as a reflection of the class-capital cleavage (Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). This dimension encompasses issues such as taxes v. spending, the structure of the welfare state, redistribution, deregulation, privatization, and risk protection. Yet, under the influence of new social movements, initially, and radical right parties, later, a second dimension of contestation has emerged. This one is cultural, encompassing party differences in lifestyle choices, sexual mores, the nature and role of the traditional family, and immigration. At the heart of these differences lies one fundamental question: how open should society be to social changes, especially those that stem from processes of secularization and globalization? Observers of European politics now by and large agree that both economic and cultural differences shape party competition and support (Binding et al., Reference Binding, Koedam and Steenbergen2024; Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010; Dassonneville, Fournier, and Somer-Topcu Reference Dassonneville, Fournier and Somer-Topcu2022; Gidron Reference Gidron2022; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006).

We build on this theoretical and empirical work to take the most parsimonious and generalizable form of multidimensionality as our starting point: two-dimensionality (see also Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2012).Footnote 1 Analytically, these potential dimensions should be distinguished. As an empirical matter – and for reasons we shall discuss below – they may be effectively highly correlated, however.

The potential-effective distinction for the dimensionality of the political space plays a crucial role in our multidimensional conception of party polarization (see below). We illustrate the distinction here using the examples of Portugal and the Netherlands. The latter example shows very clearly why it is essential to take multidimensionality seriously when analyzing party polarization.

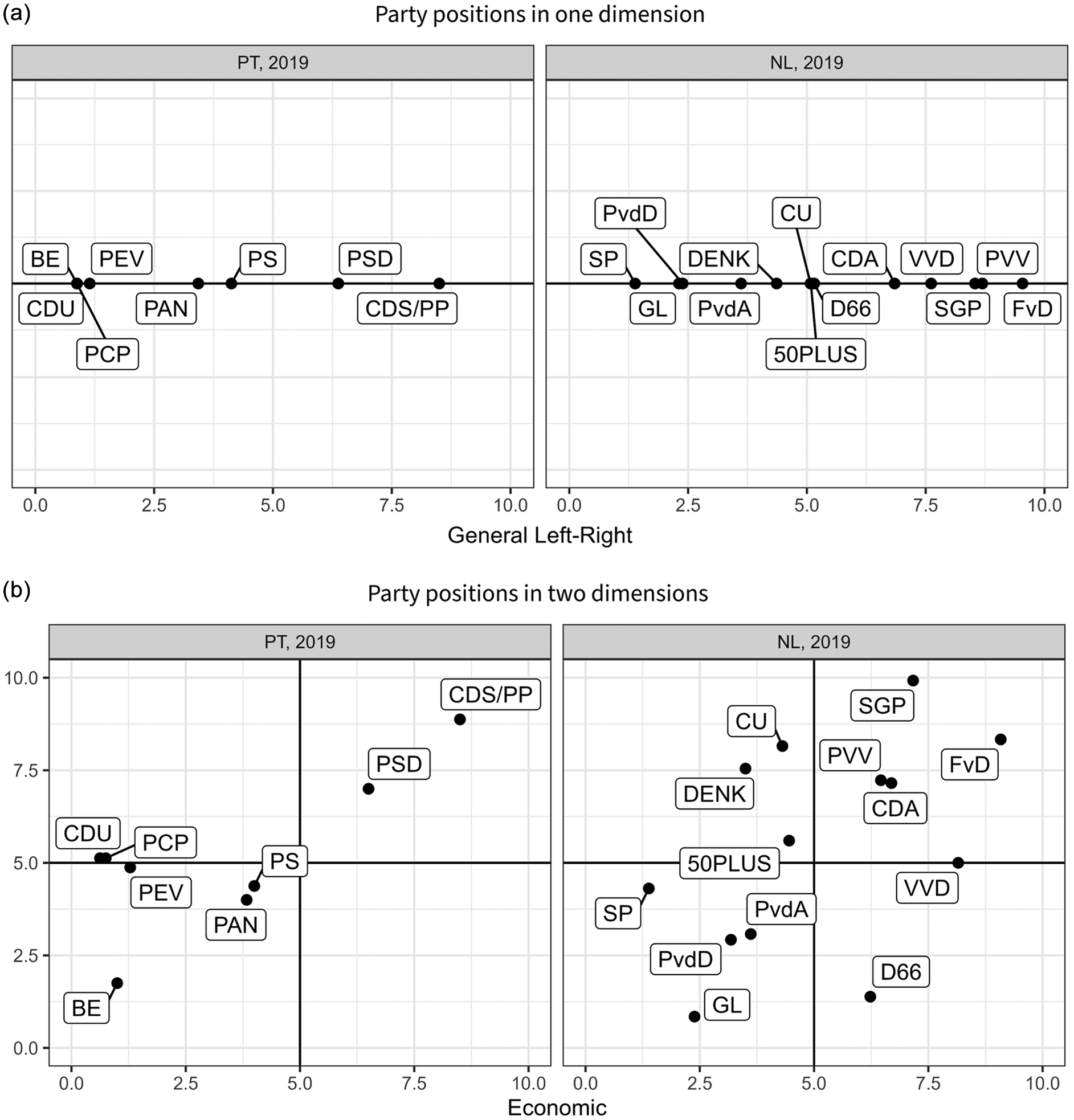

Figure 1 shows the positions of Portuguese and Dutch political parties in 2019. In panel (a) this is done for a single left-right dimension; in panel (b), a two-dimensional ideological space is drawn with economic and cultural axes.Footnote 2 Higher values represent more economically right-wing and culturally conservative positions, respectively.

Figure 1. Mutually reinforcing (Portugal) v. cross-cutting (the Netherlands) party polarization.

Note: Party positions in one (general left-right) v. two (economic and cultural) dimensions by country. Party position estimates derived from CHES (2019).

The left side of the Figure pertains to Portugal. We can see that, in panel (b), party positions in the two-dimensional space form a nearly perfect line, running from BE, on the one hand, to CDS/PP, on the other. Although CDU, PCP, and PEV – the green and communist parties – break this pattern, the departure from one-dimensionality appears mild. The notion that a single dimension can describe the Portuguese party system is consistent with Freire (Reference Freire, Niedermayer, Stöss and Haas2006). Indeed, if we project the party positions on the diagonal axis spanned by BE and CDS/PP, we pretty much obtain the placement of the Portuguese parties on the general left-right axis, as shown in panel (a). Here, then, is a case where conceiving party polarization in terms of a single dimension would not distort our picture of Portuguese party politics too much.

We can contrast this with the Dutch case, depicted on the right-hand side of Fig. 1. Panel (b) clearly reveals that party positions diverge on both economic and cultural matters, a situation that has characterized Dutch politics for the past thirty years (Middendorp, Luyten, and Dooms Reference Middendorp, Luyten and Dooms1993). Any attempt to condense the whole of the Dutch party conflict into a single dimension would thus seem to be ill-fated.

If we were to try anyway, for example, by using a general left-right dimension, we would immediately run into problems. We can illustrate this with the examples of CU and D66, a confessional and a social-liberal party, respectively. In panel (a), these parties end up in nearly identical positions on the left-right axis. This masks the vast ideological differences between the two parties that exist on the cultural dimension and that are clearly shown in panel (b).

This nuance is important for our understanding of polarization. For example, the Rutte III coalition, which governed in 2019, was made up of VVD, CDA, D66, and CU. Looking at panel (a), one would conclude that there was little intra-coalition polarization. Panel (b) warrants an entirely different conclusion, however. On cultural matters, in particular, there was a great deal of potential conflict. This explains why the coalition agreement took numerous cultural issues off the agenda, such as euthanasia.Footnote 3 This decision would not have made sense if we were to focus on panel (a) instead of panel (b).

The Dutch and Portuguese examples offer important lessons. A single ideological dimension does not always do justice to the political divisions between parties. In fact, one-dimensional polarization measures may mask a great deal of politically relevant conflict if the ideological space is effectively two-dimensional. The bottom line is that we need a multidimensional polarization measure that accounts for the effective (distinct from the potential) number of dimensions in which parties compete.

Herein also lies our theoretical contribution. By considering the effective number of dimensions, we build a bridge between two distinctive views of polarization. In the literature, the dominant view has been to view polarization in variational terms; ideological dispersion is what matters for polarization (Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Sartori Reference Sartori, La Palombara and Weiner1966).Footnote 4 There is a smaller literature, however, that views polarization in terms of constraint; the connection of cognitions and attitudes that might hitherto have been disconnected (Baldassari and Gelman Reference Baldassari and Gelman2008). Our theoretical position is that one needs both elements to fully capture polarization. Constraint without variance does not generate polarization; variance is a necessary condition for polarization. However, constraint fundamentally alters the nature of polarization. When there is a high level of constraint, that is, when dimensions of contestation effectively collapse onto each other and the effective number of dimensions is reduced, then divisions are mutually reinforcing. When there is a lower level of constraint, that is, dimensions are more or less independent, then divisions become cross-cutting. These are qualitatively different forms of polarization with different consequences, as we shall see.

The Effective Number of Dimensions in a Political Space

Much of the literature, including the oft-cited work by Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1984), concerns itself with potential dimensionality. That work identifies the issue bundles on which some disagreement exists in the public sphere. From a theoretical perspective, for instance, any party disagreement over economic, cultural, and perhaps other issues could produce a two- or higher-dimensional space.

Whether this space materializes is a different matter altogether. Sani and Sartori (Reference Sani, Sartori, Daalder and Mair1983) draw a distinction between dimensions of identification and the space of competition (see also Freire Reference Freire, Niedermayer, Stöss and Haas2006). The latter is the empirically identifiable space in which political parties operate. This space determines the supply side of electoral democracy.

In a spatial understanding of polarization, the role of agency should not be underestimated (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960). The dimensionality of the political space in which parties position themselves is very much a part of the political contestation between those parties, as has been amply demonstrated in the European case (De Vries and Marks Reference De Vries and Marks2012; Rovny and Edwards Reference Rovny and Edwards2012). While it is in the interest of established parties to subsume new issues into the existing dimension(s) of party competition (Elias, Szöcsik, and Zuber Reference Elias, Szöcsik and Zuber2015), challenger parties have a strategic incentive to introduce new dimensions by politicizing a set of ignored issues that divide the base of established parties (De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020; Meguid Reference Meguid2005).

To reflect this, we speak of the potential and the effective dimensionality of the space of competition, respectively. The effective dimensionality of a political space is frequently smaller than its potential dimensionality, as a reflection of the power balance between different partisan agents. The lower effective dimensionality reflects the re-framing and incorporation of certain dimensions into others. The result is that potential dimensions become highly correlated. That correlation can be interpreted from a variety of theoretical perspectives. Cleavage theorists might label effective dimensionality as the degree of cross-cuttingness (for example, Simmel Reference Simmel1908), formal modellers as the degree of separability (for example, Enelow and Hinich Reference Enelow and Hinich1984), and scholars of ideology as the degree of constraint (for example, Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964).

The advantage of the term effective dimensionality is its very precise meaning and operationalization in information theory (Del Giudice Reference Del Giudice2020; Roy and Vetterli Reference Roy and Vetterli2007). In that literature, effective dimensionality (henceforth, ED) is the number of uncorrelated dimensions needed to capture the correlational structure among a set of variables. As before, our starting point is two potential dimensions, and those variables are the economic and cultural ideological stances of political parties.Footnote

5

In this two-dimensional setting, ED captures the extent to which two potential dimensions effectively reduce to one. Specifically, ED is a number between 1 and 2. If

![]() $ED = 2$

, then the potential dimensions are fully realized empirically, meaning that the party stances on the economic and cultural dimensions are orthogonal. If

$ED = 2$

, then the potential dimensions are fully realized empirically, meaning that the party stances on the economic and cultural dimensions are orthogonal. If

![]() $ED = 1$

, then the potential dimensions collapse into one. Theoretically, one can distinguish between economic and cultural ideological stances, but, empirically, party positions on those dimensions correlate perfectly in this scenario. We can also say that the ideological conflicts are mutually reinforcing, that positions are non-separable, or that there is perfect constraint. In practice, ED lies between 1 and 2, with values closer to 1 indicating a more one-dimensional party system and values closer to 2 suggesting a more two-dimensional setting.

$ED = 1$

, then the potential dimensions collapse into one. Theoretically, one can distinguish between economic and cultural ideological stances, but, empirically, party positions on those dimensions correlate perfectly in this scenario. We can also say that the ideological conflicts are mutually reinforcing, that positions are non-separable, or that there is perfect constraint. In practice, ED lies between 1 and 2, with values closer to 1 indicating a more one-dimensional party system and values closer to 2 suggesting a more two-dimensional setting.

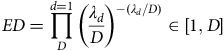

Computationally, ED uses the eigenvalues of the correlation matrix over the potential dimensions. Specifically,

$$ED = \prod\limits_D^{d = 1} {{{\left( {{{{\lambda _d}} \over D}} \right)}^{ - ({\lambda _d}/D)}}} \in [1,{\mkern 1mu} D]$$

$$ED = \prod\limits_D^{d = 1} {{{\left( {{{{\lambda _d}} \over D}} \right)}^{ - ({\lambda _d}/D)}}} \in [1,{\mkern 1mu} D]$$

(Del Giudice Reference Del Giudice2020; Roy and Vetterli Reference Roy and Vetterli2007, for a derivation, see Appendix B). Here, the

![]() $\lambda $

s are the eigenvalues and

$\lambda $

s are the eigenvalues and

![]() $D$

is the number of potential dimensions, in our case 2, but more generally any number greater than one. Del Giudice (Reference Del Giudice2020) argues that ED is an excellent all-around measure of the effective number of dimensions.

$D$

is the number of potential dimensions, in our case 2, but more generally any number greater than one. Del Giudice (Reference Del Giudice2020) argues that ED is an excellent all-around measure of the effective number of dimensions.

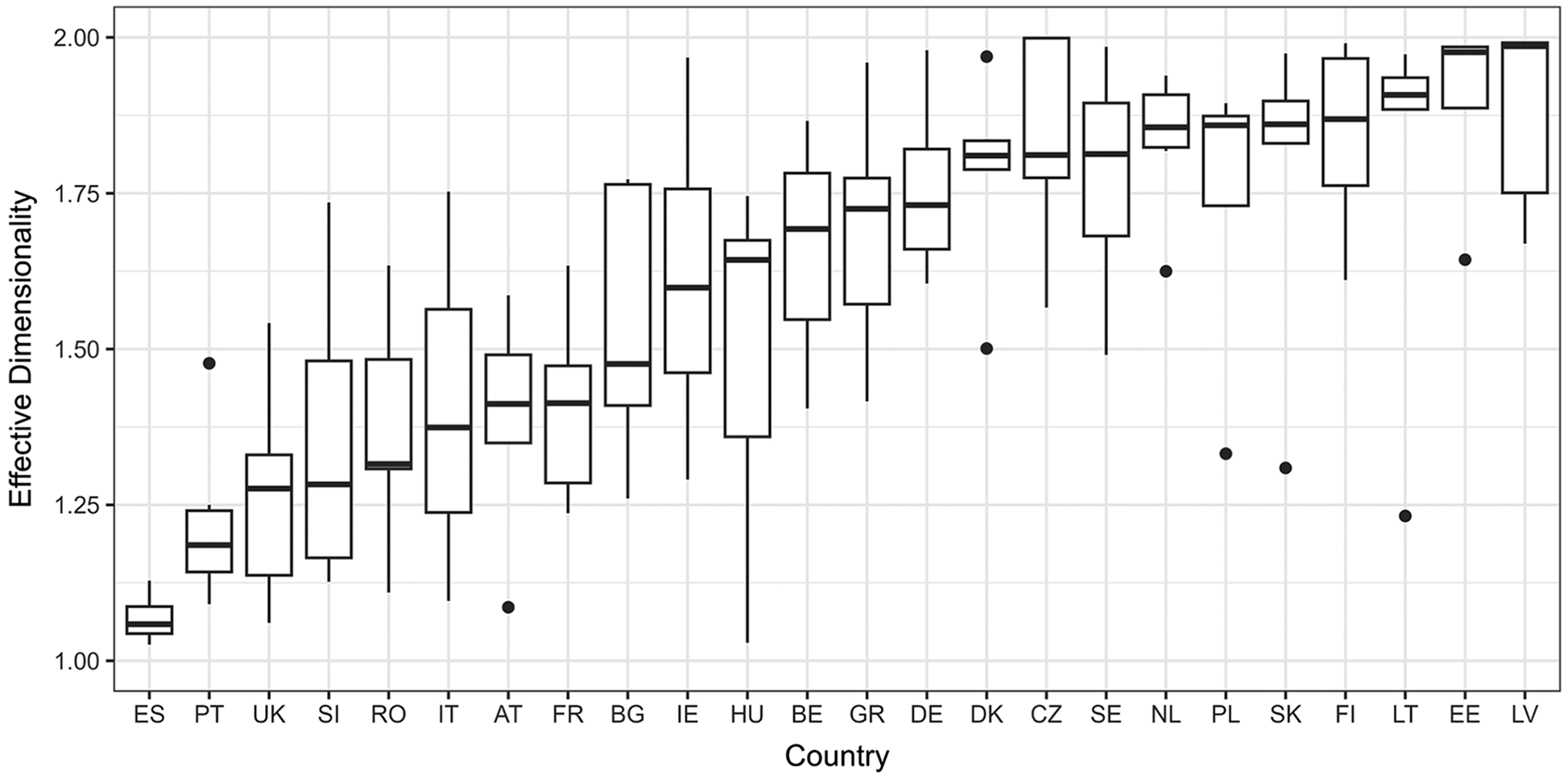

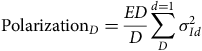

What does ED look like in Europe between 1999 and 2019? Figure 2 shows ED by country, with the boxes and whiskers reflecting the over-time variation in the effective number of dimensions in each country. Here and in the following, parties are always weighted by vote share to account for differences in party size when calculating the correlation matrix that lies at the origin of ED. The countries with the smallest effective number of dimensions include Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom.Footnote 6 Three countries with high median effective dimensionality include Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania. The former two consistently show a high score, while the effective number of dimensions has occasionally been closer to one in Lithuania. The Netherlands and Portugal, the two countries used to motivate the consideration of whether ideological divides are cross-cutting or reinforcing, stand at opposite ends of the scale.

Figure 2. Effective dimensionality by country.

Note: Box plot of effective dimensionality by country. The size of the boxes represents within-country variation over time. Party position estimates derived from CHES (1999–2019).

The effective number of dimensions can be of interest in its own right for the study of party systems. However, we believe it to be particularly important for our understanding of polarization. While a one-dimensional view of polarization may work well for countries with EDs closer to 1, it will not for party systems with an ED closer to 2. We now turn to present a multidimensional conception of polarization that integrates both ED and positional variation.

Measuring Multidimensional Polarization

What is the nature of multidimensional polarization in Europe from 1999 to 2019? We answer this question by developing a novel measurement approach that builds on the ideas of effective dimensionality and variance. Focusing on general left-right ideology, the brunt of the literature has measured polarization by considering variance in party positions (for example, Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Gidron, Adams, and Horne Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Hobolt and Hoerner Reference Hobolt and Hoerner2020). We extend this one-dimensional approach to the multidimensional setting by combining variances along the different dimensions with the novel concept of effective dimensionality, introduced in the previous section. Building on examples in two dimensions, we show that the resulting measures of multidimensional polarization follow a similar intuition to those for one-dimensional polarization.

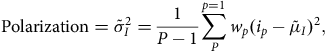

One-Dimensional Polarization

Variance-based measures of one-dimensional polarization generally combine information on parties’ positions and sizes (that is, vote shares) to calculate the weighted variance of party positions (for example, Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Sigelman and Yough Reference Sigelman and Yough1978; Taylor and Herman Reference Taylor and Herman1971). More formally, for

![]() $P$

parties, their positions in a single dimension can be represented by a vector

$P$

parties, their positions in a single dimension can be represented by a vector

![]() $I$

of length

$I$

of length

![]() $P$

:

$P$

:

![]() $I = [{i_{p = 1}}, \ldots, {i_{p = P}}]$

, where

$I = [{i_{p = 1}}, \ldots, {i_{p = P}}]$

, where

![]() ${i_p}$

is a party’s position, and its size can be represented by a vector

${i_p}$

is a party’s position, and its size can be represented by a vector

![]() $W = [{w_{p = 1}}, \ldots, {w_{p = P}}]$

of equal length, where

$W = [{w_{p = 1}}, \ldots, {w_{p = P}}]$

of equal length, where

![]() ${w_p}$

is a party’s size. Combining these pieces of information, the weighted variance of parties’ positions can be calculated as:

${w_p}$

is a party’s size. Combining these pieces of information, the weighted variance of parties’ positions can be calculated as:

$${\rm{Polarization}} = \tilde \sigma _I^2 = {1 \over {P - 1}}\sum\limits_P^{p = 1} {{w_p}} {({i_p} - {\tilde \mu _I})^2},$$

$${\rm{Polarization}} = \tilde \sigma _I^2 = {1 \over {P - 1}}\sum\limits_P^{p = 1} {{w_p}} {({i_p} - {\tilde \mu _I})^2},$$

where

![]() ${\tilde \mu _I}$

is the vector’s weighted mean.

${\tilde \mu _I}$

is the vector’s weighted mean.

In addition to being the most widely used, the attractiveness of a variance-based approach is that it incorporates information from all parties (rather than focusing on the most extreme parties in a range-based approach) and that it builds on a known and intuitive statistic (rather than calculating the sum of pairwise distances). These considerations motivate our use of a variance-based approach to measure multidimensional polarization.

Multidimensional Polarization

A naive approach to multidimensional polarization would be to simply generate variance-based polarization metrics per dimension and then add them. However, this approach would fail to distinguish between party systems where the dimensions are uncorrelated and effective dimensionality is high v. those where they are strongly correlated and effective dimensionality is low. As a result, the measure might exaggerate the level of party polarization.

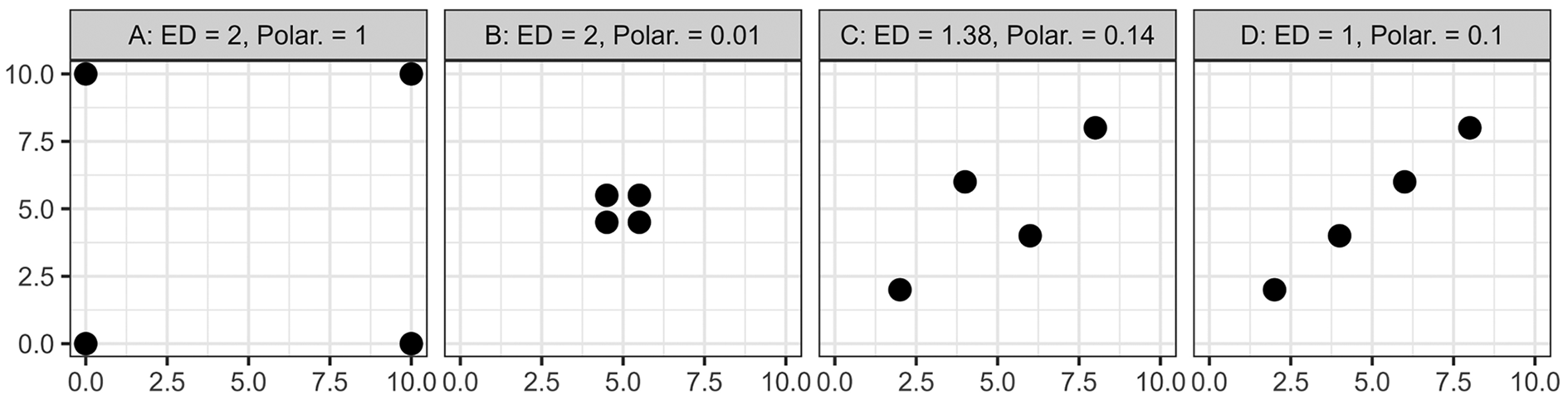

We follow a different approach by taking the effective number of dimensions into account. To understand the rationale of our approach, consider the four hypothetical party systems shown in Fig. 3, each with four equally-sized parties positioned differently along two dimensions. Three parameters are being varied: (1) the variance along the first dimension; (2) the variance along the second dimension; and (3) the correlation between the positions on the two dimensions.

Figure 3. Examples of two-dimensional party polarization.

Note: Hypothetical examples of party polarization in two dimensions, each consisting of four equally-sized parties. The effective dimensionality and two-dimensional party polarization values are shown at the top of each space.

The argument for the inclusion of the variances along each dimension in a measure of multidimensional polarization is straightforward given the comparison between examples A and B in Fig. 3. If parties are equally distributed at the dimensional extremes (example A), thereby maximizing the variance along each dimension, then a measure of multidimensional polarization should distinguish this from a scenario in which parties are located around the centre of the two-dimensional space (example B), where variances along the dimensions are smaller.

However, equal variances along dimensions need not imply equal polarization. Consider the examples C and D. In these two cases, the variances along the individual dimensions are equal across the two examples, as identical positions are taken by different parties on each dimension. Yet, party positions are perfectly correlated in D, while they are not in C. Simply summing the variances across dimensions would neglect this difference, as C and D would result in identical measures. A measure of multidimensional polarization should be able to distinguish the more polarized scenario C from the less polarized scenario D. In the latter case, political conflict essentially plays out along a single empirical dimension that represents a mixture of the two potential dimensions, so that the effective space of political conflict is reduced to a one-dimensional setting.

Figure 3 highlights the importance of considering the effective number of dimensions in a polarization measure that generalizes to

![]() $D$

-dimensional space. Thus, we propose the following, intuitive measure of multidimensional polarization:

$D$

-dimensional space. Thus, we propose the following, intuitive measure of multidimensional polarization:

$${\rm{Polarizatio}}{{\rm{n}}_D} = {{ED} \over D}\sum\limits_D^{d = 1} {\sigma _{Id}^2} $$

$${\rm{Polarizatio}}{{\rm{n}}_D} = {{ED} \over D}\sum\limits_D^{d = 1} {\sigma _{Id}^2} $$

When we take the ratio of the naive measure and our measure, we obtain the factor

![]() $D/ED$

. This shows that the naive measure tends to exaggerate polarization: unless

$D/ED$

. This shows that the naive measure tends to exaggerate polarization: unless

![]() $ED = D$

, the naive measure exceeds our measure, since it keeps adding the variances of dimensions that are, to a greater or lesser degree, redundant.Footnote

7

Similar to the variance-based measures for one-dimensional polarization, our measure can account for variation in party size by calculating a weighted variance-covariance matrix based on parties’ positions and sizes, and use

$ED = D$

, the naive measure exceeds our measure, since it keeps adding the variances of dimensions that are, to a greater or lesser degree, redundant.Footnote

7

Similar to the variance-based measures for one-dimensional polarization, our measure can account for variation in party size by calculating a weighted variance-covariance matrix based on parties’ positions and sizes, and use

![]() $\tilde \sigma _{Id}^2$

(rather than

$\tilde \sigma _{Id}^2$

(rather than

![]() $\sigma _{Id}^2$

).

$\sigma _{Id}^2$

).

Returning to the four artificial examples of Fig. 3, our approach aptly identifies example A as the most and example B as the least polarized party system in two dimensions, while also highlighting C as more polarized than D. Both the calculated values of effective dimensionality (bound between 1 and 2) and polarization are presented at the top of each space. The polarization values are normalized relative to the maximum extent of polarization possible so that values are constrained between 0 (when all parties are located at the same position) and 1 (when

![]() ${2^D}$

equally-sized parties are positioned at the extremes of the individual dimensions, as in example A). In the next step, we turn to describing the resulting party polarization measures in a one- and a two-dimensional setting.

${2^D}$

equally-sized parties are positioned at the extremes of the individual dimensions, as in example A). In the next step, we turn to describing the resulting party polarization measures in a one- and a two-dimensional setting.

Validation of Measurement Strategy

How does our measurement strategy for multidimensional polarization fare when we turn to the real world? To answer this question, we compare party positions on a general left-right, an economic, and a cultural dimension, as provided by the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES; Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022).Footnote 8 Some have raised concerns that expert estimates might obscure expert disagreement or country differences (for example, Lindstädt, Proksch, and Slapin Reference Lindstädt, Proksch and Slapin2020; McDonald, Mendes, and Kim Reference McDonald, Mendes and Kim2007), but the advantage of these data is that they provide direct, dimensional estimates of party ideology. Moreover, the positions have been shown to correlate strongly with placements derived from alternative sources (for example, Steenbergen and Marks Reference Steenbergen and Marks2007), not least voter perceptions of parties (Dalton and McAllister Reference Dalton and McAllister2015). Importantly, our approach applies to any source of party positional estimates, including election manifestos.

We proceed to validate our approach in three steps (Adcock and Collier Reference Adcock and Collier2001). First, we assess whether the resulting multidimensional measures aptly distinguish between more and less polarized party systems in two dimensions (content validation). Second, we consider the extent to which multidimensional polarization is correlated with one-dimensional polarization (convergent validation). Third, we turn to other known correlates of polarization and estimate whether or not associations with one-dimensional polarization also hold for multidimensional polarization (construct validation).

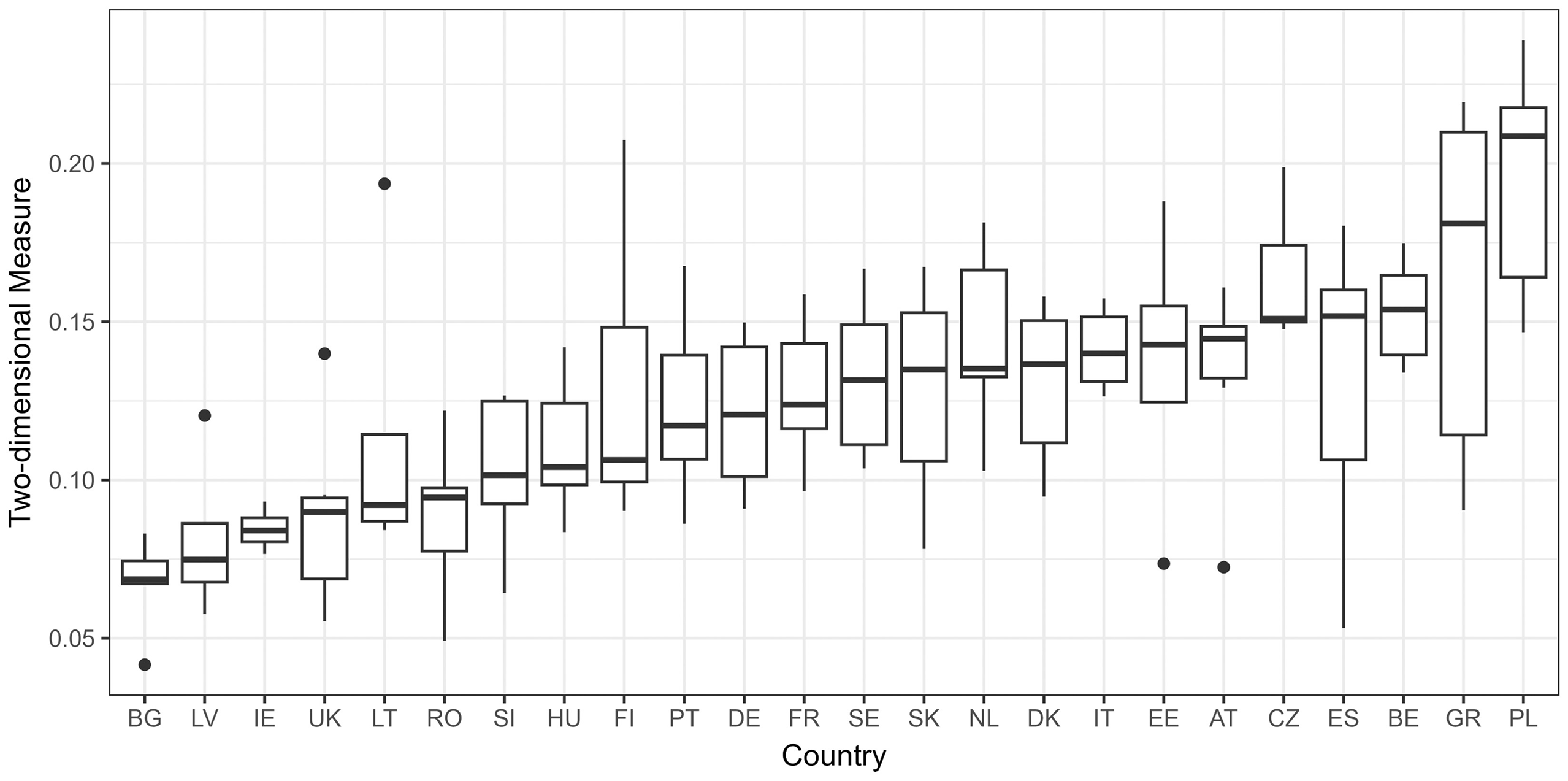

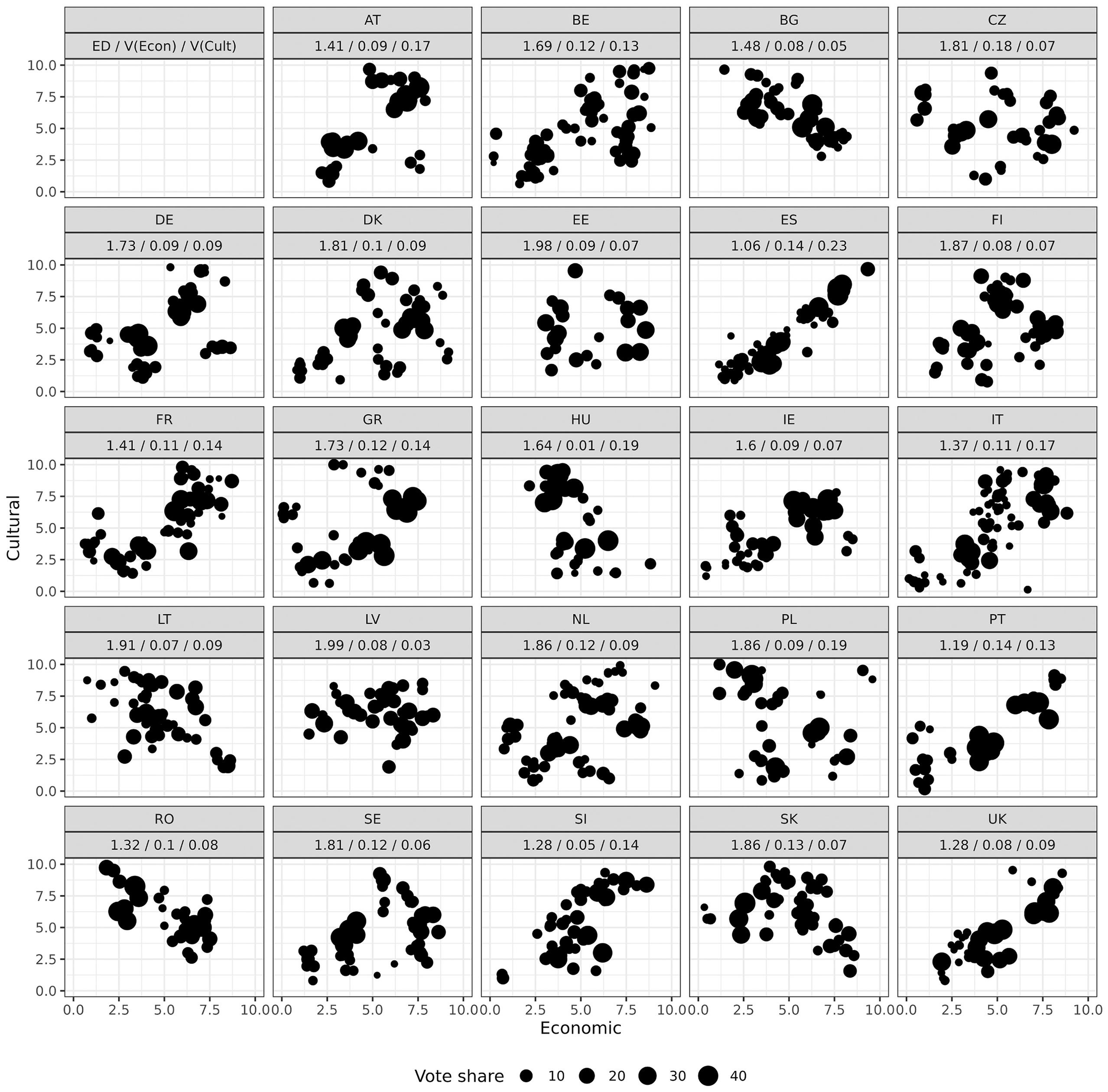

Where are the resulting measures of polarization in two dimensions high or low, and do the resulting values correspond with the actual distribution of party positions? Figure 4 displays the variation in the resulting measures of

![]() ${\rm{Polarizatio}}{{\rm{n}}_D}$

across countries, calculated by country and survey wave. As before, raw values are standardized to fall between 0 and 1. On average, multidimensional polarization is high in Poland, Greece, and Belgium, and low in Bulgaria, Latvia, and Ireland. As this measure is a combination of three moving parts – effective dimensionality and variance along either of the two dimensions – its value depends on variation in any of these components.

${\rm{Polarizatio}}{{\rm{n}}_D}$

across countries, calculated by country and survey wave. As before, raw values are standardized to fall between 0 and 1. On average, multidimensional polarization is high in Poland, Greece, and Belgium, and low in Bulgaria, Latvia, and Ireland. As this measure is a combination of three moving parts – effective dimensionality and variance along either of the two dimensions – its value depends on variation in any of these components.

Figure 4. Two-dimensional party polarization by country.

Note: Box plot of party polarization in two dimensions by country. The size of the boxes represents within-country variation over time. Party position estimates derived from CHES (1999–2019).

To unpack this, we can plot the divergent spatial distributions of parties in two dimensions across Europe. Merging the CHES survey waves, Fig. 5 illustrates that, similar to the hypothetical examples of Fig. 3, the association of party positions across dimensions varies between countries. Some show a clear left-progressive to right-conservative diagonal (for example, the United Kingdom or, as discussed, Portugal), some exhibit a mirror image with a diagonal that runs from left-conservative to right-progressive (for example, Bulgaria or Romania), while others suggest that party positions are uncorrelated across dimensions (for example, Estonia or Finland). In addition, important for our purposes here, Fig. 5 sheds light on why multidimensional polarization may be higher – that is, more spatially dispersed – in some places than in others. Looking at the effective dimensionality and standardized weighted variance along either dimension (see median values below each country label), relatively high multidimensional polarization tends to be found in systems that combine high effective dimensionality with high variances along both dimensions (for example, Belgium or Greece). By contrast, low levels of multidimensional polarization are mainly the product of lower variances, not effective dimensionality (for example, Ireland or Latvia).

Figure 5. Two-dimensional political space by country.

Note: Party positions in two dimensions (economic and cultural) by country, pooling the different survey waves. The size of the circles represents a party’s vote share. The median values for effective dimensionality and party polarization (standardized weighted variance by dimension) are shown at the top of each space. Party position estimates derived from CHES (1999–2019).

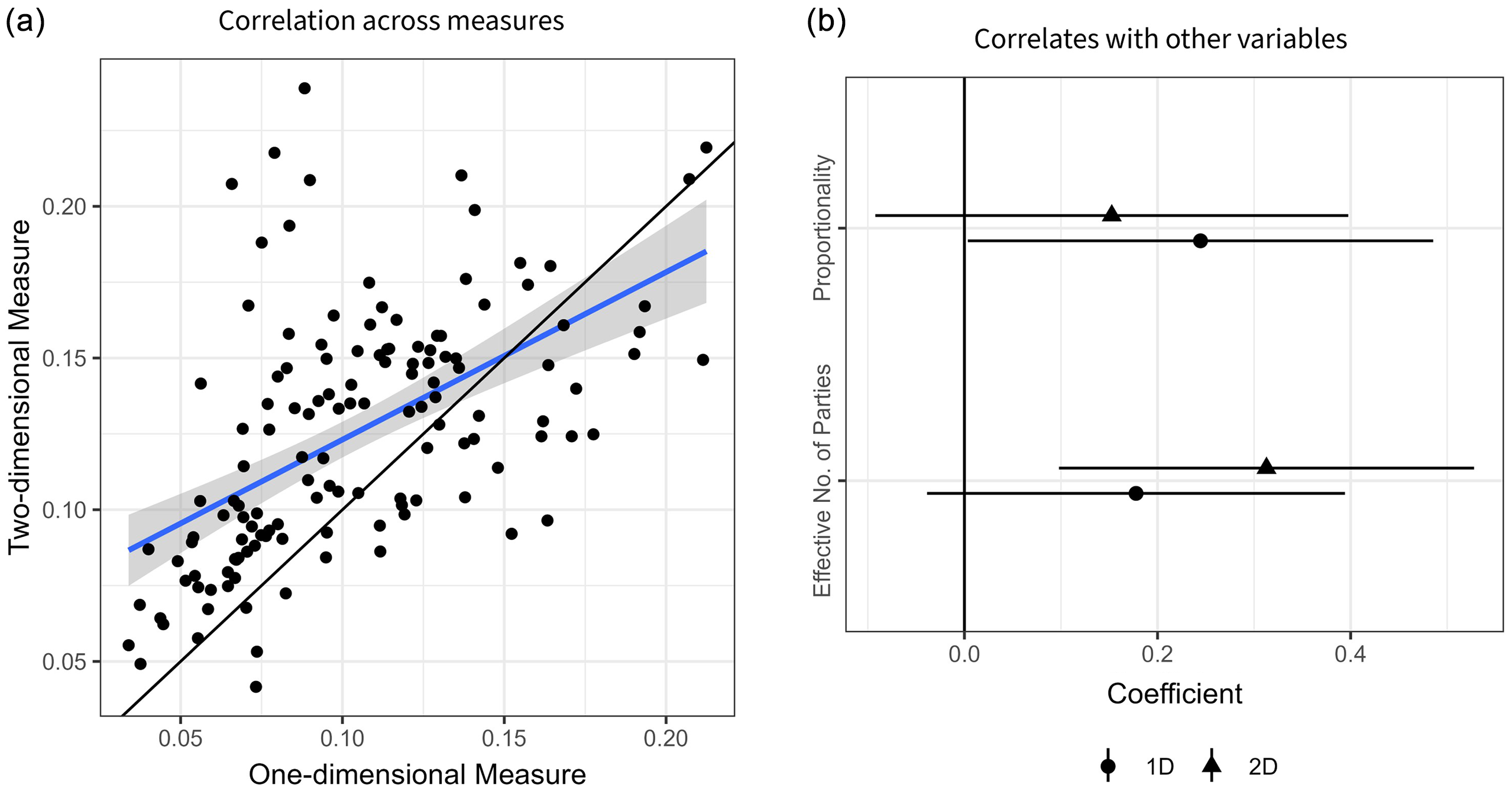

Next, we explore whether the resulting measures of one- and multidimensional polarization are correlated (indicating that they tap into a similar underlying concept of party polarization), and under which conditions they diverge. Figure 6a contrasts the standardized measures by country and survey wave, where one-dimensional polarization is calculated as the weighted variance of party positions on the left-right dimension. The correlation between the two measures is positive and substantial with

![]() $\rho = 0.55$

. This makes sense: we would expect party competition on economic and cultural issues to be reflected in a general left-right dimension more broadly. That is, effective polarization in a multidimensional conceptualization of the political space should be related to polarization in a more general one-dimensional conceptualization. But we would also expect there to be aspects in a left-right dimension that are not reflected in either an economic or cultural dimension (see, for example, Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2012), so it is similarly sensible that the correlation between the two measures is not perfect.

$\rho = 0.55$

. This makes sense: we would expect party competition on economic and cultural issues to be reflected in a general left-right dimension more broadly. That is, effective polarization in a multidimensional conceptualization of the political space should be related to polarization in a more general one-dimensional conceptualization. But we would also expect there to be aspects in a left-right dimension that are not reflected in either an economic or cultural dimension (see, for example, Benoit and Laver Reference Benoit and Laver2012), so it is similarly sensible that the correlation between the two measures is not perfect.

Figure 6. Comparison of one- and two-dimensional party polarization measures.

Note: Panel (a) shows the association between party polarization in one (x-axis) v. two dimensions (y-axis). Each dot represents a country-survey year. The thin line illustrates perfect correlation, and the thick line (with confidence interval) represents the observed correlation between the two measures; Panel (b) plots the coefficient estimates for proportionality and the effective number of parties for both the one- and the two-dimensional party polarization measure (represented by circles and triangles, respectively).

Under which conditions are the one-dimensional and multidimensional polarization measures more similar? This should be the case when the correspondence between parties’ positions on the general left-right and the two potential dimensions – the economic and the cultural dimension – is higher, and polarization conceptualized in one or two dimensions is interrelated. Moreover, the two measures should be more similar if the weighted variance on the left-right dimension is similar to the average weighted variance of the two dimensions. We assess this via a multi-level regression with the difference between the two measures as the dependent variable and as independent variables the effective dimensionality of party positions in two dimensions, as well as the difference between the weighted variance on the left-right dimension and the average weighted variance on the two dimensions (see Table C1 in Appendix C). The results are in line with our expectations: measures of polarization are more similar if the effective dimensionality across the two dimensions is low and if variances on the two dimensions are of similar size as for the general left-right dimension.

Finally, to assess construct validity, we look at the known correlates of the systematized concept of polarization (Adcock and Collier Reference Adcock and Collier2001). The expectation is that the same associations exist for both the conventional one-dimensional and our multidimensional measures. Empirical research highlights the importance of electoral rules, as polarization tends to be higher in more proportional systems and systems with more parties (for example, Dalton, Reference Dalton2021; Dow Reference Dow2010). We assess these associations using both the one- and the multidimensional measure as dependent variables, and proportionality (measured as the difference between parties’ vote and seat shares; Gallagher Reference Gallagher1991) and the effective number of parties (measured via parties’ seat shares; Laakso and Taagepera Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979) as independent variables.

The estimated coefficients of both proportionality and the effective number of parties are shown in Fig. 6b (mean and 95 per cent confidence intervals). The coefficient sizes represent changes in standard deviations, as non-categorical variables are z-transformed prior to estimation throughout. The coefficients of the two variables are equal in their direction and statistically indistinguishable from each other across the two specifications (that is, the differences of the estimated coefficients across polarization measures are not significantly different from 0; for full regression tables, see Table C2 in Appendix C). This shows the construct validity of the proposed measure, as it correlates similarly with other variables otherwise related to the concept.

Party Polarization and Mass Partisanship

To explore the substantive implications of our approach, we analyze the relationship between party polarization and mass partisanship. As discussed, the ideological differentiation between parties can affect voter attitudes and behaviour, including their political engagement (for example, Adams, De Vries, and Leiter Reference Adams, De Vries and Leiter2012a; Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019; Dassonneville, Fournier, and Somer-Topcu Reference Dassonneville, Fournier and Somer-Topcu2022; Hobolt and Hoerner Reference Hobolt and Hoerner2020; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2010). Specifically, party polarization can increase the likelihood that a voter indicates feeling close to a party. Different theories have been proposed to explain this relationship – for example, party polarization clarifies what parties stand for, makes them more salient in elections, or increases the perceived utility of voting for them (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989; Franklin and Jackson Reference Franklin and Jackson1983; Jackson Reference Jackson1975) – but there is consistent evidence for this positive association between party polarization and mass partisanship, both in the US context (for example, Hetherington Reference Hetherington2001) and comparatively (Lupu Reference Lupu2015).

Crucially, these studies rely on a one-dimensional left-right conception of party polarization. We argue that this measure is less suited to pick up the anticipated relationship with partisanship in more multidimensional contexts. Regardless of the exact mechanism(s) at play, a second, cross-cutting dimension should affect party-voter relations. Going back to the Dutch example from Fig. 1, for example, the misrepresentation of the cultural differences between parties from a one-dimensional conception may lead us to underestimate their ideological polarization and how it informs voters seeking to identify the party that best represents them. Indeed, that cultural differences matter is also evident from studies by Adams, Ezrow, and Leiter (Reference Adams, Ezrow and Leiter2012b) and Dassonneville, Fournier, and Somer-Topcu (Reference Dassonneville, Fournier and Somer-Topcu2022), who show that cultural and multidimensional party positions are key for understanding voters’ evolving ideological preferences and partisan attachments. This highlights the importance of employing a measure that is sensitive to this aspect of political conflict.

Below, we empirically analyze the relationship between mass partisanship and party polarization using our novel multidimensional measure as the key independent variable. Building on Lupu (Reference Lupu2015), we rely on the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) to measure our outcome variable, that is, whether a respondent feels close to a party (an indicator widely used to gauge partisanship). We similarly use perceptions of party positions, albeit expert instead of voter evaluations, as we continue to work with CHES. Substantially, however, these differences are negligible.Footnote 9 Combining the five CSES modules with CHES data, we have information on 73 elections across 24 European countries.Footnote 10

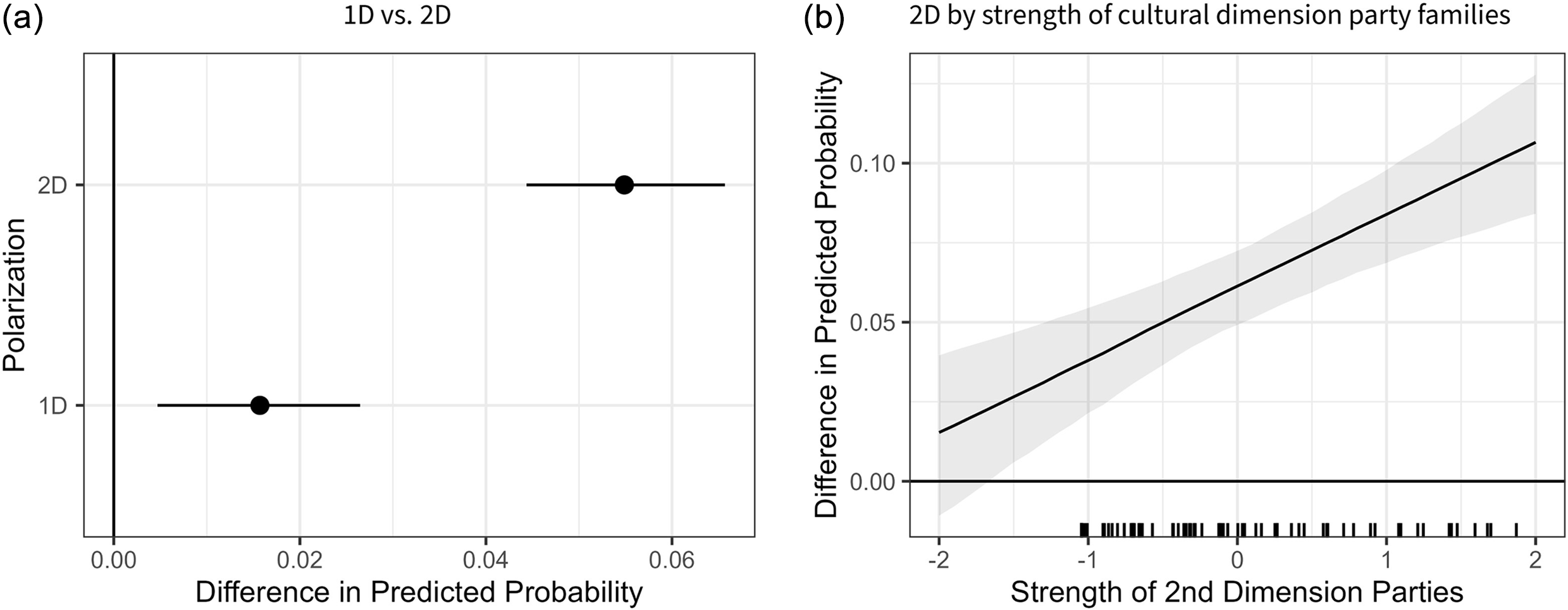

Starting with the generalized effect, we are able to replicate the findings of previous comparative research (Lupu Reference Lupu2015). Our results document a positive relationship between party polarization and mass partisanship, which is visible in Fig. 7a (for the full regression results, see Table E1 in Appendix E).Footnote 11 The figure shows the difference in the predicted probability of a respondent identifying as a partisan when party polarization increases from 0 to 1 standard deviation (holding all other factors constant at their mean or reference category). When using one-dimensional polarization, respondents are about 1.6 per cent more likely to feel close to a party when polarization increases. When focusing on multidimensional (here, two-dimensional) polarization, this difference increases to roughly 5.5 per cent, which constitutes a relative increase by a factor of 3.5. This is a substantial change, given that this is a generalized effect, averaged across all included countries (the difference is likely even greater when looking only at contexts that are effectively two-dimensional). Evidently, polarization matters for mass partisanship, and multidimensional polarization matters more than one-dimensional polarization in the European context.

Figure 7. Party polarization and mass partisanship.

Note: Panel (a) plots the difference in the predicted probability of a respondent identifying as a partisan for a one-standard-deviation increase in one- and two-dimensional party polarization (1D and 2D, respectively); Panel (b) shows the difference in the predicted probability for two-dimensional party polarization, conditional on the electoral strength of cultural dimension party families.

Up to now, our focus has been on a generalized effect, across different national contexts. To unpack this finding further, our interest turns to a conditional relationship between multidimensional party polarization and mass partisanship. In particular, we have so far focused on parties’ ideological polarization (in either one or two dimensions) but ignored the relative weight of dimensional conflict. These two things need not be identical: parties may be ideologically polarized on a dimension, but not engage with this dimension in party competition. To assess the potential of such a conditional effect, we estimate a model in which multidimensional party polarization interacts with the electoral strength of ‘second dimension’ party families – for whom cultural issues are relatively more salient (see Koedam Reference Koedam2022) – as a proxy of the relative importance of this dimensional conflict.Footnote 12

As before, Fig. 7b presents the difference in the predicted probability of a respondent being a partisan for a one-unit increase from 0 to 1 standard deviation in multidimensional polarization. Now, however, this difference varies with the electoral strength of cultural dimension party families. As these parties increase in importance, multidimensional polarization becomes more relevant for how partisan citizens are: if the strength of cultural dimension parties is set to −1 standard deviation, the difference in predicted probabilities is roughly 3.8 per cent. This more than doubles to around 8.4 per cent when their electoral strength is at the value of 1 standard deviation. In other words, the relative weight of conflict on this dimension matters for how multidimensional party polarization is related to mass partisanship.Footnote 13

Discussion

This study offers a novel approach to evaluate party polarization in the context of multidimensional, fragmented politics. We have shown that taking multidimensionality seriously enhances our understanding of polarization and its consequences. This is particularly important for comparative research in Europe, which has to contend with multidimensional conceptions of ideological conflict, and where a one-dimensional left-right representation of party polarization may be inappropriate.

It is important to stress once more that our approach does not impose a dimensionality on the space in which political battles are fought. While our starting point here is two dimensions, it can also be three or more.Footnote 14 The theoretical and methodological intuition would remain the same. Crucially, we allow for the possibility that the dimensions are correlated to a smaller or larger degree. For our measure, then, one-dimensional polarization is simply a special case of multidimensional polarization that comes about when the dimensions are mutually reinforcing.

Likewise, our approach does not prejudge the nature of the dimensions along which party conflict unfolds. In this study, we focus on economic and cultural polarization, because these have received the most attention in the comparative literature. But, depending on the party system, one could bring in other conflict lines that may or may not be cross-cutting. In Spain, for example, it may be appropriate to substitute a centre-periphery divide into our measure, while in other contexts the European issue might constitute a third dimension.

More generally, we should acknowledge that a one-dimensional polarization measure stated in general left-right terms may be unable to detect important nuances in polarization across numerous democracies. As we have demonstrated, such a measure can neither capture the cultural differences between parties nor account for the full effects of party polarization on mass partisanship. Our approach offers the degree of flexibility required to deal with situations where economic and cultural conflicts are to some degree cross-cutting.

Mass partisanship, of course, is only one arena where the effects of multidimensional polarization can be explored. We believe the concept and our measure to be relevant for several key literatures in political science. The comparative study of political behaviour, for example, could use it to better understand outcomes like voter turnout or affective polarization. Students of political parties can use our approach to evaluate the state of political conflict in party systems, including party system fragmentation. As the Dutch example of the Rutte III coalition highlights, comparative studies of political institutions may use it to understand government formation and survival, but also policy agendas. The study of democracy could correlate our measure with democratic stability. Finally, we see potential for conflict studies, because our focus ultimately is on the nature of institutionalized political divisions. In all of these areas, our approach could provide new insights that may remain obscured with a one-dimensional conceptualization and operationalization of polarization (and dimensionality).

While exploring multidimensional polarization in various fields, there is, of course, the potential to refine and unpack our measure. It could be worthwhile, for example, to take into consideration the salience of various dimensions of political conflict. One might expect that parties attach more importance to polarized divides, but this is an empirical question. Importantly, comparative data on the multidimensional attitudes of voters are much needed to explore whether a similar measure can be constructed for the mass public, which would allow for a comparison of party and mass polarization across multiple dimensions.

As a final consideration, our focus has been on party polarization as ideological distinctiveness. Spatial dispersion and conflict intensity are logically connected in a single dimension, but it remains to be seen whether the multidimensional positional divergence of parties exacerbates or attenuates the detrimental impact of political conflict. While mutually reinforcing political conflict can be a fragmenting force that manifests itself in bitter fights among politicians and possibly the masses, cross-cutting divides have been theorized to reduce conflict (Dahl Reference Dahl1956; Lipset Reference Lipset1959; Simmel Reference Simmel1908). We leave this normatively important question, as well as the other extensions, for future research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000474.

Data availability statement

Replication Data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/T3Y1ZQ.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Attewell, André Blais, Diane Bolet, Simon Bornschier, Laurence Brandenberger, Ruth Dassonneville, Noam Gidron, Silja Häusermann, Simon Hix, Sara Hobolt, Liesbet Hooghe, Gerardo Iñiguez, Herbert Kitschelt, Giorgio Malet, Gary Marks, Fabian Neuner, Jonathan Polk, Frank Schweitzer, Jae-Jae Spoon, Cheryl Vaterlaus, and Markus Wagner, as well as the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and support. Previous versions of this paper were presented at the University of Montreal and the University of Zurich, annual conferences of APSA, CES, DVPW, and EPSA, as well as the workshops ‘RETHINK’ at the University of Pittsburgh, ‘Lessons of post-functionalism’ at the European University Institute, and ‘Measuring, modeling, and mitigating opinion polarization and political cleavage’ at ETH Zurich.

Financial support

Jelle Koedam acknowledges funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF Ambizione Grant, No. 216463).

Competing interests

None.