Over the last decade, there has been substantial growth in research into the role of nutraceutical and dietary interventions in psychiatry(Reference Berk and Jacka1). Observational studies in both adults and children have identified a broad range of nutrient-dense dietary patterns that are inversely associated with several psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and particularly depression(Reference Gianfredi, Dinu and Nucci2–Reference O’Neil, Quirk and Housden5). The converse has also been demonstrated for Western dietary patterns(Reference Gianfredi, Dinu and Nucci2,Reference Lane, Gamage and Travica6) . Furthermore, crucial to informing our understanding of the efficacy of nutraceutical and dietary interventions are a growing number of published randomised controlled trials in Nutritional Psychiatry. Meta-analytic studies of clinical trials provide varying levels of support for nutraceutical interventions across a broad range of psychiatric conditions(Reference Firth, Teasdale and Allott7–Reference Johnstone, Hughes and Goldenberg9). For example, a meta-review of thirty-three meta-analyses (n 10 951 individuals) found highly variable evidence for specific individual nutraceuticals in a given disorder and high variability in evidence for specific nutraceutical compounds across a range of psychiatric conditions(Reference Firth, Teasdale and Allott7). There are also an increasing number of randomised controlled trials that provide evidence for the use of dietary interventions in psychiatry for both adults and children(Reference Campisi, Zasowski and Shah10,Reference Firth, Marx and Dash11) . These include the Mediterranean diet for people with depression(Reference Firth, Marx and Dash11–Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt15), or elimination diets for people with ADHD(Reference Pelsser, Frankena and Toorman16). Emerging trials have also investigated dietary interventions in other psychiatric disorders such as autism(Reference Quan, Xu and Cui17) and bipolar disorder(Reference Saunders, Mukherjee and Myers18). In response to this developing evidence, recent clinical guidelines have been published by the International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research and the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry(Reference Marx, Manger and Blencowe19–Reference Sarris, Ravindran and Yatham21), which aim to improve translation of this evidence into practice.

However, recent guidelines have also cited methodological limitations such as small sample sizes, issues with fidelity or transparency of the composition of intervention, limitations with control conditions and blinding, and inconsistent reporting of key trial details as being common within the current literature(Reference Sarris, Ravindran and Yatham21). For example, a recent systematic review and network meta-analysis of nutraceuticals in schizophrenia reported an average sample size of n 47 across the fifty studies included(Reference Fornaro, Caiazza and Billeci22). Similarly small sample sizes have also been reported in dietary interventions(Reference Bizzozero-Peroni, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Fernández-Rodríguez23). Such limitations can affect the reliability, validity, reproducibility, and generalisability of the trial results and their translation into real-world settings. There are also various areas of research that are currently understudied. For example, while there are several dietary intervention trials conducted in people with depression and in people with ADHD, evidence for other psychiatric conditions is sparse(Reference Campisi, Zasowski and Shah10,Reference Firth, Marx and Dash11,Reference Aucoin, LaChance and Cooley24,Reference Aucoin, LaChance and Naidoo25) . In schizophrenia, for example, most research on diet has focused on addressing metabolic syndrome rather than core psychiatric symptoms of the disorder(Reference Aucoin, LaChance and Cooley24). This selective focus has led to a gap in our understanding and overlooks the potential benefits or risks of dietary interventions in less explored conditions. Furthermore, for psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder, several dietary interventions have focused on the Mediterranean diet whereas other diets (e.g. a low carbohydrate diet) have not been evaluated in controlled trials(Reference Bizzozero-Peroni, Martínez-Vizcaíno and Fernández-Rodríguez23,Reference Dietch, Kerr-Gaffney and Hockey26) . Studying other dietary approaches might unveil further effective strategies for psychiatric conditions. These gaps must be addressed in future clinical trials. Hence, the aim of these guidelines from the International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research is to provide guidance to clinical trial investigators for improving the quality and uniformity of clinical trial methodology, conduct, and reporting in Nutritional Psychiatry. These guidelines are designed to complement and be used in conjunction with other established nutrition-specific(Reference Lichtenstein, Petersen and Barger27), general reporting (e.g. CONSORT), ethical, and trial conduct guidelines (e.g.(Reference Schulz, Altman and Moher28–Reference Mirzayi, Renson and Zohra31)).

Methods

Definitions

For these guidelines, we define whole diet interventions as any dietary intervention that aims to modify the intake of multiple food groups (e.g. Mediterranean diet, high fibre diet, and ketogenic diet). In contrast, food supplementation interventions focus on modifying the intake of a specific food item (e.g. consuming a fermented dairy product). We also use the term ‘nutraceutical’ to refer to interventions that consist of nutrients, compounds or microorganisms that are typically present in food and are delivered as a capsule or powder formulation.

Scope and target audience

The recommendations included in these guidelines are designed to inform both nutraceutical and dietary (e.g. whole diet, food supplementation) clinical trial interventions in Nutritional Psychiatry. The recommendations are broad, aiming to improve quality across a diverse range of mental health conditions and methods. As the Nutritional Psychiatry evidence-base advances, more specific guidelines tailored to particular conditions, interventions or methods may provide targeted recommendations. While some included recommendations are applicable to many types of intervention studies (rather than Nutritional Psychiatry specifically), they are included due to the inconsistent application of these recommendations within the current Nutritional Psychiatry clinical trial literature. For example, the inclusion of people with lived experience in the design of trials is recommended by several peak bodies (e.g.(Reference Fisher, Fones and Arivalagan32,33) ); however, we were unable to find any prior studies included in a relevant systematic review that described inclusion of this expertise in the trial development(Reference Firth, Marx and Dash11). We acknowledge that not all recommendations will be appropriate for all trial designs and settings. Instead, rather than being a prescriptive set of guidelines, it is ultimately the purview of the investigator team to determine the suitability of the following recommendations in addressing the aims and research question of the individual trial. Similarly, most recommendations included in these guidelines are aimed at trials using efficacy study designs rather than effectiveness designs as this is how most of Nutritional Psychiatry research is currently being conducted, as indicated by recent systematic and scoping reviews in the field(Reference Aucoin, LaChance and Cooley24,Reference Aucoin, LaChance and Naidoo25) . These guidelines are also aimed at informing investigator-initiated trials in Nutritional Psychiatry but may also be informative for industry sponsored trials. Finally, in recognition of the rapidly evolving research in the field of Nutritional Psychiatry, these guidelines should not be considered static; they are intended to be subject to regular reviews and updates as the field develops.

Guideline development process

Using a similar approach to prior ISNPR guidelines(Reference Guu, Mischoulon and Sarris34), recommendations were developed using a Delphi process (Fig. 1). In August 2023, the two lead authors (WM and HMS) established a working group of eighteen researchers with considerable clinical trial expertise and experience in either nutraceutical or dietary interventions in psychiatry. Investigators were primarily identified via reviewing members of relevant working groups and committees within the ISNPR and by reviewing previously published papers in Nutritional Psychiatry.

Figure 1. Guidelines development process.

To generate an initial series of recommendations, two authors (WM and HMS) developed a questionnaire that asked the working group to provide recommendations pertaining to the following five categories: trial design considerations, participants, intervention, comparator, outcome, as well as any additional miscellaneous recommendations that did not fit these categories (online Supplementary Material). This questionnaire was designed to be open ended to capture a broad range of possible recommendations based on the individual researchers’ previous experience with clinical trials.

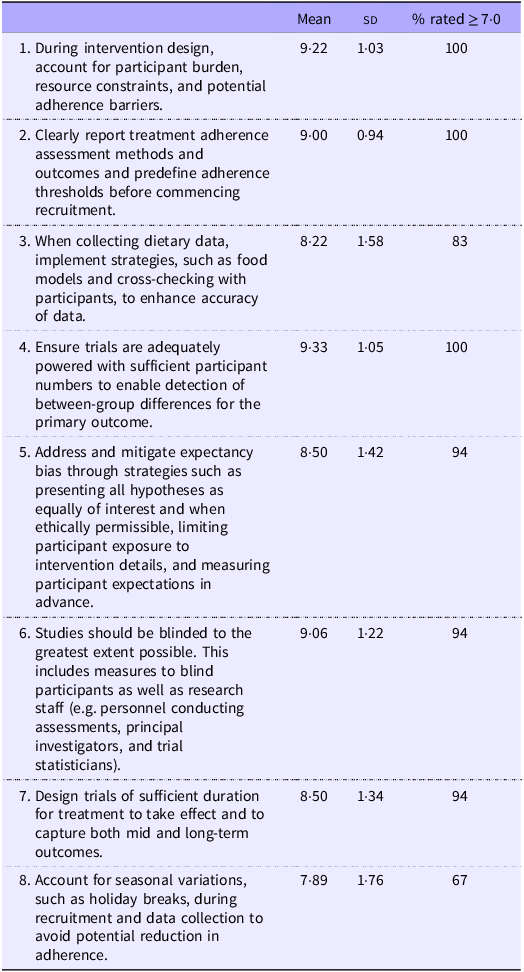

These submissions were then collated and refined by the lead authors to remove duplicate recommendations and to ensure consistent phrasing. From this, a ten-point Likert questionnaire was developed using REDcap(Reference Harris, Taylor and Minor35,Reference Harris, Taylor and Thielke36) , whereby investigators were then asked to rate each recommendation from the refined list based on their level of agreement (0 – strongly disagree, 10 – strongly agree) or select ‘No answer’ if the specific recommendation was outside of their expertise. Recommendations that received an average of equal to or greater than 7 were included in the final manuscript, where the phrasing was further refined to improve clarity and uniformity. All excluded recommendations are available in the online Supplementary Material.

While this approach was designed to ensure a wide range of recommendations and to avoid potential bias caused by leading questions, we do acknowledge that such bias may still persist. Furthermore, consolidating similar responses into a single statement by the two lead authors (WM and HMS) may have introduced bias and possible misinterpretation of original statements.

Clinical trial recommendations

Following the described process, we established forty-nine recommendations related to clinical trial design and outcomes (i.e. trial team, trial design, participants, intervention, comparator and outcome), five recommendations related to trial reporting and seven related to future research priorities. Here, we present all recommendations grouped by a specific methodological aspect and provide a discussion and summary of the background literature for the identified major themes.

Trial team-related recommendations

Team composition

Ensuring relevant expertise and stakeholders are involved in trial design and conduct is likely to improve the rigor, feasibility, and clinical relevance of trial outcomes (Table 1). Dietitians accredited/registered with national governing bodies are particularly important to treatment delivery of whole diet interventions. Preliminary sub-group analyses of trials in psychiatric populations suggest dietitian-delivered interventions may provide a greater effect sizes in both depressive symptoms and metabolic outcomes(Reference Firth, Marx and Dash11,Reference Rocks, Teasdale and Fehily37) . This is understandable given the specialised skills needed to assess and provide dietary counselling to individuals, e.g. for addressing barriers and ambivalence to change, supporting optimal dietary adherence, and managing common co-morbid conditions such as disordered eating. This is particularly likely when the dietitian has experience and training within the mental healthcare setting. They are also best placed to collect and verify dietary data, as supported by a recent study demonstrating that 93 % of participant-completed diet records contained errors prior to dietitian verification(Reference Barnett, Mayr and Keating38).

Table 1. Trial team-related recommendation statements

A further important consideration is the inclusion of stakeholder and consumer input in all phases of the trial, from conception and design through to dissemination. For intervention studies, this may involve people with lived experience of the investigated mental disorder whereas prevention studies may also include individuals from the general community. The inclusion of such expertise, via co-design or working groups, improves the feasibility and value of the intervention to participants and people with mental disorders. Because of these improvements, inclusion of lived experience is also increasingly expected from the general community, as well as the scientific community (e.g. major funding bodies, journals). Recently developed frameworks such as The Involvement Matrix(Reference Smits, van Meeteren and Klem39) aim to support participant involvement in research projects and can be used both prospectively to discuss the possible roles of stakeholders in different phases of projects and retrospectively to reflect on whether those roles were carried out satisfactorily.

Trial design-related recommendations

Participant burden

Prior literature and consumer feedback notes the negative effects of substantial participant burden on recruitment and participant adherence(Reference Ulrich, Ratcliffe and Zhou40). Hence, the investigator team should carefully consider the quantity of and methods by which data are collected from participants in relation to the level of burden this poses to them (Table 2). This can be achieved through consultation with people with lived experience, qualitative workshops and feedback from prior participants, avoiding recruitment during periods where adherence is more difficult (e.g. major holidays; recommendation #8), careful consideration of instruments and the order in which they are administered to assess eligibility or to capture participant data, and thorough pilot testing and subsequent refinement of the trial protocol. Moreover, chosen outcome measures should take into consideration symptom presentations and cognitive impairments prevalent in specific psychiatric populations (e.g. cognitive dysfunction, anhedonia) that may affect a participant’s ability and willingness to reliably complete the outcome measures.

Table 2. Trial design-related recommendation statements

Participant adherence

All trials should define intervention adherence a priori and then use that definition to measure adherence to the intervention to enable reporting and analysis of outcomes in the context of participant adherence. For example, previous trials have demonstrated a greater treatment response in participants who had a larger level of adherence compared with those with a lower level of adherence(Reference Jacka, O’Neil and Opie12,Reference Bot, Brouwer and Roca41) . Tracking adherence trajectories throughout the duration of the trial may also be useful, particularly for refining processes that may be contributing to low adherence. There are several methods to assess adherence, and all have limitations that need to be considered by the trial investigators. Biological methods (e.g. blood levels of a nutrient in a nutrient supplementation trial) may offer an objective marker of intervention adherence but are more invasive than other methods. Self-reported methods (e.g. diet records) are inexpensive but are inherently prone to error and require additional dietetic time for participant training and record verification. Furthermore, researcher-reported endpoints (e.g. group session attendance) can be consistently measured by research staff but may be limited in precision, particularly in dietary interventions. For example, recording attendance to intervention sessions as a marker of adherence may not capture data related to participants leaving early or low levels of engagement.

Blinding and expectancy bias

An important issue raised in previous publications is the challenge of participant expectancy – where the expectations or beliefs of the participants contribute to their treatment response. This may be particularly pertinent to nutrition interventions compared with pharmaceutical interventions as individuals may hold strong beliefs about food and diet(Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Drewnowski42). Whole diet interventions are also exceedingly difficult to blind, increasing the risk of unequal expectancy across groups. Broadly, expectancy can have implications for retention, as participants wanting to be assigned to the treatment group may drop out if they believe they have been assigned to the control group. Trial findings may also be affected as participants knowingly assigned to the control group may experience poorer mental health outcomes and/or participants knowingly assigned to the treatment may experience amplified mental health outcomes, both leading to overestimation of true treatment effects. Where ethically possible, designing advertising and participant information and consent materials to conceal the primary research hypothesis may help mitigate expectancy bias. Other trial design methods such as placebo run-in phases have also been proposed to reduce the number of placebo responders and enhance the chance of detecting a treatment effect; however, large meta-analyses of these study designs in the antidepressant literature have not been supportive(Reference Scott, Sharpe and Quinn43). Whilst methodologically challenging and resource-intensive, whole diet interventions should ideally be conducted with a placebo diet control. This is addressed further in section 3·5.

Follow-up duration

There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend a specific minimum duration for nutraceutical or dietary trials in Nutritional Psychiatry. Many recent dietary intervention trials have reported clinical effects in depression over a 12-week timeframe(Reference Jacka, O’Neil and Opie12,Reference Parletta, Zarnowiecki and Cho13,Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt15) ; however, improvements have also been reported in as little as 3 weeks(Reference Francis, Stevenson and Chambers14). Nutraceutical intervention trials generally vary from 4 to 12 weeks. Prevention studies over one to 5-year periods have also been conducted in both dietary and nutraceutical interventions although have not reported improvements in onset or reoccurrence of depressive symptoms(Reference Bot, Brouwer and Roca41,Reference Cabrera-Suárez, Hernández-Fleta and Molero44,Reference Okereke, Vyas and Mischoulon45) . Determining trial duration should be guided by prior trials, mechanistic, and pharmacokinetic understanding of the bioactive components (particularly in the case of nutraceutical interventions) and feasibility considerations. A further consideration is that there are few intervention trials monitoring treatment effect beyond 6 months, which limits understanding of long-term feasibility, efficacy, and safety of interventions. This is important especially in the context of other fields of behavioural science (e.g. dietary interventions targeting weight loss for obesity) that show reduced adherence in longer intervention programs compared with dietary interventions of < 3 months.

Participant-related recommendations

Recruitment practises and generalisability of trial population

Efficacy trials have historically been conducted in populations that are highly selected and seldom generalisable to the real-world clinical environment(Reference Rothwell46). Key drivers of this are recruitment methods and intervention content that fail to reach or appeal to a broader population. To address this, efficacy trials should implement inclusive recruitment practices and strategies that promote diversity in relevant demographic factors (e.g. age, gender, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and rurality; Table 3). This may involve leveraging community organisations and digital platforms to reach underrepresented groups. Incorporating flexible scheduling, teleconference visits, and/or participant travel reimbursement may improve accessibility and convenience of participating in trials and enhance participant diversity and representation. Furthermore, detailed reporting of demographic characteristics and post hoc analyses examining intervention effects across various subgroups can provide context to the generalisability of the findings to the wider target population.

Table 3. Participant-related recommendation statements

Consideration of comorbid conditions

There is a high prevalence of both physical and psychiatric comorbidity in people with mental disorders(Reference Berk, Köhler-Forsberg and Turner47). For example, one-third of total nonfatal burden in people with depression is estimated to be due to comorbid physical diseases and other studies report that people with depression have a substantially increased risk of eating disorders, as well as other psychiatric comorbidities, compared to the general population(Reference Berk, Köhler-Forsberg and Turner47,Reference Garcia, Mikhail and Keel48) . This high prevalence of comorbidity may affect treatment outcomes by introducing safety risks via increased drug–nutrient interactions, altering implicated mechanisms of action (e.g. Crohn’s disease altering the gut microbiota), and increasing risk of safety concerns (e.g. lipid profiles in people with comorbid coronary heart disease). Investigators should consider how to identify, manage, and examine treatment efficacy and safety in participants with a potential vulnerability to having an existing condition triggered by their participation such as eating disorders and disordered eating. Identification during the screening process is important for dietary interventions, and particularly those that involve any type of dietary restriction or food elimination, as these may trigger or exacerbate disordered eating behaviours. It is common practice in efficacy trials to exclude participants with common comorbidities to improve the homogeneity of the participant sample; however, this has also been criticised for reducing external validity and generalisability of the trials results(Reference He, Morales and Guthrie49). Another approach is to employ an effectiveness design including ‘all-comers’ with an aim to reflect ‘real world’ clinical presentations. However, some comorbid conditions should still be considered for exclusion based on safety reasons (e.g. participants with eating disorders should not be eligible for whole diet trials requiring dietary restriction).

Consideration of ceiling and floor effects

Investigators should consider both potential floor and ceiling effects when selecting trial participant eligibility criteria. The floor effect, whereby participants exhibit low baseline scores in the variable of interest (e.g. baseline depressive symptoms), and therefore, only small improvements are possible, reduces the likelihood of separation between the intervention and control condition. For example, investigating an intervention in a participant sample in which baseline depressive symptoms are already low may impair the likelihood of seeing a treatment effect, particularly without a large sample size. Low baseline levels of depressive symptoms were cited as a possible explanation for the fewer than expected number of transitions to Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) in the large MoodFOOD prevention trial (10 % after 12 months v. an expected 33 % based on previous studies)(Reference Berk and Jacka1,Reference Bot, Brouwer and Roca41) . Similarly, consideration of a possible ceiling effect should be applied when selecting the eligibility criteria for a trial. For example, high baseline diet quality of participants could lead to a ceiling effect in trials evaluating the effect of a high diet quality whole diet intervention on depressive symptoms. Several prior dietary intervention trials in this field have included diet quality screening tools as part of their eligibility criteria to mitigate this issue(Reference Jacka, O’Neil and Opie12–Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt15).

Intervention-Related Recommendations

Research question-informed trial design

Investigators should ensure that the selected study design is best suited to address the intended research question (Table 4). This is particularly relevant to dietary intervention trials where there are a variety of possible delivery options (e.g. dietary counselling, controlled feeding trials, or their combination) and where there are potentially other aspects of the intervention that may influence treatment outcomes. For example, motivational interviewing and other commonly used behavioural components may independently influence mental health outcomes by improving feelings of mastery, behavioural activation, improved locus of control, and self-efficacy. Therefore, if the trial is intended to investigate the therapeutic value and/or biological mechanisms of a whole diet intervention, a controlled feeding trial may be preferable. In these trials, most/all food is provided and dietary counselling is not necessary. Although costly and intensive, these trials also have the added benefit of being amenable to double blinding and facilitating strict adherence. Collinearity is another complexity that should be considered in interpretation of whole diet and food supplementation trials. This is the phenomenon in which increasing or decreasing intake of foods or food groups can influence background dietary intake that in itself could influence outcomes. Similarly, the choice of delivering the intervention as a stand-alone intervention, adjunct to psycho- or pharmaco- therapy, or multicomponent should be guided by the intended research question, the qualifications, and credentials of the lead investigator and should consider how results of the trial could feasibly be integrated into clinical practice. Formal tools such as the PRECIS-2 tool may be used to ensure the trial design and decisions are in line with the intended purpose of the trial(Reference Loudon, Treweek and Sullivan50).

Table 4. Intervention recommendation statements

Standardising dietary and nutraceutical interventions

Dietary interventions are complex interventions, and their design requires consideration of several factors to ensure effectiveness and replicability. First, in contrast to drug or nutraceutical interventions where there is generally a higher level of uniformity in how the intervention is administered, dietary interventions require additional procedures to ensure intervention fidelity, reproducibility, scalability and, ideally, nutritional adequacy for participants. These include processes such as manualising the intervention delivery procedure, additional and ongoing training of the trial staff that are delivering the intervention to ensure standardisation, and conducting fidelity testing and audits of intervention delivery. The degree of standardisation may also differ by trial design. Efficacy trials may seek a higher level of standardisation to ensure a highly precise and ‘optimal’ delivery of the intervention, whereas an effectiveness trial may deliver the intervention on a personalised basis depending on client characteristics and other clinical considerations and staff resources, to reflect real world delivery. Standardisation is also an important consideration of nutraceutical interventions, particularly for herbal or plant-based formulations, in which the nature and dose(s) of the bioactive component(s) may vary considerably(Reference Harkey, Henderson and Gershwin51,Reference Marx, Isenring and Lohning52) . This can be facilitated by independent testing for bioactive constituents as well as using formulations that standardise to a specific bioactive content.

Individualised and culturally applicable dietary interventions

Designing dietary interventions tailored to the circumstances of the target population is likely to result in greater appeal and participant adherence. This includes consideration for individual taste and cultural preferences. Demographic considerations such as age and gender should also be considered. For example, in relation to a recent Mediterranean diet Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) in young men with depression, Bayes et al. (Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt53) highlighted the need to consider pervasive gendered associations with specific foods (e.g. meat perceived as ‘masculine’, vegetables perceived as ‘feminine’) and how this may influence diet adherence in differing trial populations. Other relevant considerations include the cost and availability of the investigated dietary intervention, food preparation skills, available time, geographical access to foods, and treatment duration. Socio-cultural factors such as economic circumstances and health literacy are also important. Previous qualitative studies of participants undergoing a Mediterranean dietary intervention highlighted the perceived increase in costs associated with adherence to the diet as well as barriers related to increased food preparation time and availability of some food items within their region(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt54,Reference Middleton, Keegan and Smith55) . To mitigate this, prior trials have provided the costliest components of the diet (e.g. extra virgin olive oil, nuts) to participants as part of a food hamper(Reference Jacka, O’Neil and Opie12,Reference Parletta, Zarnowiecki and Cho13) . Similarly, we recommend education regarding food safety, hygiene, storage, and preparation in populations that may be unfamiliar with the intervention food items and practices. While also relevant to nutraceuticals, whole diet counselling interventions especially need to accommodate for common psychological symptoms associated with disease pathogenesis and/or medication side effects like changes in appetite, reduced cognition motivation, fatigue, and attention, which may substantially impair the ability to strictly adhere to intervention recommendations. The use of research dietitians proficient in counselling techniques is recommended to mitigate many of these potential barriers.

Weight-neutral dietary interventions

While weight loss may improve psychiatric outcomes such as depressive symptoms in people with obesity(Reference Applewhite, Penninx and Young56), prior dietary interventions suggest that weight loss is not a requirement in Nutritional Psychiatry trials for a beneficial mental health outcome(Reference Jacka, O’Neil and Opie12). This evidence is largely based on trials conducted in MDD and requires further investigation in populations where metabolic dysfunction and overweight are prominent features (e.g. schizophrenia). However, based on the currently available evidence, for dietary intervention trials in which mental health is a primary outcome, a weight-neutral approach that avoids weight-centred language or motivations should be used. This approach has additional benefits. First, such strategies help to avoid potential safety issues including reduced body dissatisfaction, disordered eating patterns, and stigma that are counterproductive to participant health. Second, preliminary evidence from other lifestyle interventions in mental disorders suggests emphasising mental health benefits, rather than physical health benefits, of an intervention may improve adherence(Reference Gellert, Ziegelmann and Schwarzer57–Reference Steinberg, Rosen and Ganz59). Finally, ensuring bodyweight stability avoids the challenge of dissecting whether improvement in outcomes has occurred in response to the intervention or from the contemporaneous weight loss. This is particularly important in efficacy trials.

Consideration for combination or individual nutraceutical formulations

The choice to investigate a nutraceutical intervention as an individual compound or a multi-compound formulation should be guided by the primary research question. Single nutrient interventions offer greater insight into the specific clinical effect and mechanisms of a specific nutrient; however, a multi-nutrient formulation may be more representative of dietary consumption, their actions in vivo, and possibly offers synergistic effect(Reference Popper, Kaplan and Rucklidge60,Reference Sarris, Logan and Akbaraly61) .

Comparator recommendations

Comparator selection

The gold standard trial design for assessing treatment efficacy in pharmaceutical trials is the placebo-controlled randomised controlled trial. The design of placebos in pharmaceutical trials is relatively straightforward; a pill can be designed to exactly match the treatment in appearance, taste, and even texture, whilst being ‘inert’ (i.e. inactive) and free of the drug under investigation, meaning participants can be blinded to their treatment allocation. In most cases, nutraceutical trials can also be tested in a blinded placebo-controlled fashion relatively easily as they usually investigate a treatment delivered as a pill or powder. Plant-derived nutraceutical interventions with distinct smells (e.g. ginger supplementation) are an exception to this and where the smell of the placebo condition requires consideration. Diet interventions, however, are exceedingly difficult to investigate in a placebo-controlled fashion as no foods or diets are ‘inert’ and cannot be easily blinded. In the case of food supplementation trials, in which an alternative food with the same energy content is provided in the control arm, the intent of the trial can be masked to mitigate the risk of unequal expectation bias across groups (Table 5). In the case of whole diet trials, placebo diets can be implemented but are challenging to design and deliver; however, as above, these should be considered the gold standard where resources allow(Reference Staudacher, Irving and Lomer62). Feeding trials, in which all food and fluid is provided to participants, can facilitate blinding and placebo control. Whole diet counselling trials are more difficult to placebo control, and as such, there has been no placebo-controlled trial of a whole diet counselling intervention to date. Instead, common control conditions that have been previously used in superiority trials include befriending protocols(Reference Jacka, O’Neil and Opie12). These are non-dietary approaches that can control for the level of engagement and support provided by being involved in a research study, although do not exactly match the motivational counselling that is often provided in dietary counselling trials. Recommendations for the design of placebo diets, such that engagement and blinding and all aspects of diet (e.g. shopping, cooking to follow a specific diet) other than the active component are equivalent to the intervention group, have been reviewed elsewhere(Reference Staudacher, Irving and Lomer62). Non-inferiority trial designs in which treatments are compared with currently accepted interventions (e.g. antidepressant medications, psychotherapy) are important once initial efficacy has been established(Reference Young, Moylan and John63).

Table 5. Comparator recommendation statements

Outcome-related recommendations

Clinical outcome considerations

To enhance the accuracy and depth of outcome measurement, it is recommended that trials capture both self-report and clinician-rated assessments of the clinical outcome of interest, where possible (Table 6). This is particularly pertinent to trials where participants are unblinded, and self-reported outcomes may be more likely to be influenced by expectancy. As with all behavioural trials, a related important consideration is to avoid confirmation bias by ensuring clinician assessments are blinded and are not conducted by the intervention or unblinded research staff(Reference Hohenschurz-Schmidt, Vase and Scott30). To help inform future research, we also recommend that sub-domains of the primary outcome (where they are validated) are analysed in addition to total scores to investigate the effect of the interventions on individual aspects of mental health. However, investigators should also be mindful that these exploratory analyses may be underpowered when interpreting the results. Further, it is advised to measure symptoms at multiple pre-specified timepoints. This may involve momentary time sampling methods, such as ecological momentary assessment, to track the progression and fluctuation of symptoms over time, providing a more detailed picture of the effect of the intervention by capturing temporal dynamics.

Table 6. Outcome-related recommendation statements

Assessment of both psychiatric and metabolic outcomes

While there are a growing number of individual trials that have investigated the efficacy of dietary and nutraceutical interventions for psychiatric outcomes and metabolic outcomes in psychiatric samples(Reference Firth, Teasdale and Allott7,Reference Swainson, Reeson and Malik64) , many trials, particularly for dietary interventions, have not examined both sets of outcomes within the same trial. Considering the shared mechanistic pathways that are implicated in both psychiatric and physical outcomes(Reference Berk, Köhler-Forsberg and Turner47) and the substantial time, cost, and effort required for running clinical trials, it is both prudent and informative to incorporate measures of both outcome types into Nutritional Psychiatry trials.

Dietary assessment considerations

It is recommended to weigh the pros and cons of various validated dietary assessment methods and select an approach based on the study’s objective and participant burden. For example, in nutraceutical interventions, a comparably brief measure that captures broad changes in diet (e.g. clinician-administered diet history) and/or changes in the specific nutrients under investigation might be preferable whereas for a dietary intervention, a more comprehensive dietary assessment such as a food record may be required. Where evidence is supportive, incorporate validated dietary biomarkers as objective intake and/or adherence measures. For example, a spectrophotometer has been used to evaluate plasma carotenoid levels to verify adherence to a healthy eating-Mediterranean diet intervention in young adults(Reference Francis, Stevenson and Chambers14). This has also been covered within the Participant Adherence section. Furthermore, due to the well-established limitations of self-reported dietary intake, we recommend that dietary assessments are administered and verified by a dietitian (e.g. cross-checking of food records with a participant) to ensure consistent and reliable data collection. This is particularly important in serious mental illness where challenges to recall (e.g. cognitive dysfunction) are common and where most dietary assessment tools have not been validated within this participant population.

Markers of treatment response

Trial investigators are encouraged to align with precision medicine principles(Reference Fernandes, Williams and Steiner65) and consider collecting comprehensive baseline data on biological, clinical, and demographic variables that may influence treatment response. These data can facilitate the identification of specific subgroups that are particularly amenable to treatment response. For example, prior trials have suggested elevated baseline inflammatory markers may influence treatment response to nutraceutical interventions(Reference Rapaport, Nierenberg and Schettler66). Furthermore, a recent umbrella review identified a range of demographic factors that may positively (e.g. higher education status, female gender) or negatively (e.g. previous negative life events) influence treatment response to psychiatric treatments(Reference Solmi, Cortese and Vita67). However, as per the conclusions of a recent systematic review that investigated this in Nutritional Psychiatry(Reference van der Burg, Cribb and Firth68), evidence is currently preliminary, and further trials are required to investigate other unexplored factors that may influence treatment response. An important consideration in implementing these analyses is to ensure that there is adequate statistical power to detect such factors as failure to do so can increase the risk of type 2 statistical error.

Blinding assessment

Trials should assess the efficacy of the implemented blinding processes. Due to the use of subjective assessment tools (e.g. self-reported depressive symptoms), this is particularly important for psychiatric assessment; however, recent evidence suggest that blinding is rarely assessed(Reference Lin, Sahker and Shinohara69). Quantitative data on blinding efficacy provide important context for interpretation of the results. Such assessment should be undertaken for all blinded parties. For example, in a double-blind intervention, blinding assessment for both participants and research staff will be informative. This is relevant to both nutraceutical and dietary interventions alike; however, this is particularly pertinent to dietary interventions due to the complexity of introducing effective blinding procedures and the higher risk of unblinding. There are various methods proposed for implementing blinding assessments. Many trials simply ask participants to guess their allocation (i.e. treatment, control and unknown) at the end of the trial. In these cases, equal responses across groups and/or between treatment and control groups would be indicative of successful blinding. Statistical methods are also available such as the James’ and Bang’s blinding indices(Reference Bang, Flaherty and Kolahi70,Reference James, Bloch and Lee71) . Although a controversial topic, the timing of evaluating blinding success traditionally has been at the end of the trial, but it has been suggested that this may be more accurate if undertaken earlier in the trial before participants have hunches about intervention efficacy or even experience side effects as a result of receiving the intervention(Reference Sackett72). Furthermore, exploring the reasons for why participants believe they are in the intervention or control condition can be informative. For example, a higher number of participants correctly guessing they are in the active intervention may be due to a range of reasons including participants experiencing improvements in outcomes, distinct smell and presentation of the intervention (e.g. nutraceuticals), and adverse effects, all of which can influence the interpretation of blinding success.

Inform clinical translation efforts

To advance the clinical translation of trial findings, researchers are encouraged to incorporate outcomes such as cost-effectiveness and safety, acceptability, and tolerability. The latter can be assessed using validated tools and adverse reporting methods, qualitative methods such as structured clinical interviews, or implementation assessments such as through the use of the RE-AIM framework(Reference Glasgow, Vogt and Boles73). Furthermore, in addition to traditional effect size and cut-off metrics, the results should also be reported within the context of treatment costs, treatment burden, treatment-related adverse effects, and clinically meaningful differences to determine if the findings are not only statistically robust but also practically significant in a real-world setting.

Reporting recommendations

Reporting considerations

To improve replication efforts in Nutritional Psychiatry, authors are encouraged to provide detailed descriptions of all details relevant to the delivery of the intervention under investigation (Table 7). Using reporting frameworks such as Tidier and CONSORT (and its relevant extensions) are strongly encouraged throughout design, conduct, and reporting(Reference Schulz, Altman and Moher28,Reference Hoffmann, Glasziou and Boutron29) . Pre-registration of the trial with a national clinical trial registry prior to commencing recruitment is required. Publication of the trial protocol is recommended during recruitment and submission of the full study protocol submitted to the journal upon submission of results. Furthermore, as some journals have word restrictions that may prohibit detailed descriptions of all aspects of methodology and/or interventions, authors are encouraged – and indeed, this is a common requirement of many medical journals – to include these in supplementary information or to publish additional resources that provide further information such as separate publications (e.g.(Reference Opie, O’Neil and Jacka74)) or stored on publicly accessible repositories such as pre-print archives (e.g. Open Science Framework).

Table 7. Reporting recommendation statements

Funding and conflict of interest transparency

Due to the reported risk of bias associated with industry funding in medicine(Reference Lundh, Lexchin and Mintzes75), our guidelines provide strong endorsement for the need to clearly report industry funding and degree of involvement in all aspects of the clinical trial, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript development. Resources such as the recently published Food Research risK (FoRK) toolkit(Reference Cullerton, Adams and Forouhi76) may provide a structured framework to navigate these issues. Furthermore, when declaring conflicts of interests, authors are encouraged to err on the side of full disclosure, thereby allowing readers to assess the potential effect of any disclosed conflicts on the research outcomes.

Recommendations for future research

Participant populations

There are a comparably large number of nutraceutical clinical trials that have been undertaken in participants with mental disorders such as major depressive disorder. In contrast, there are relatively few trials that have investigated these same nutraceutical interventions in other mental disorders. For example, a large meta-review found nine nutraceuticals where there was meta-analytic evidence for their use in major depressive disorder compared to only two in anxiety disorders(Reference Firth, Teasdale and Allott7). This is also evident in the dietary intervention setting where there are a number of trials for mental disorders such as major depressive disorder and ADHD but few interventions for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder(Reference Pelsser, Frankena and Toorman16,Reference Aucoin, LaChance and Cooley24,Reference Aucoin, LaChance and Naidoo25,Reference Swainson, Reeson and Malik64) . Similarly, given the relative lack of prevention studies in Nutritional Psychiatry, further trials are required to investigate both nutraceutical and dietary interventions in primary and secondary prevention of mental disorders (Table 8).

Table 8. Recommendations for future research

Dietary interventions

Whole diet interventions in Nutritional Psychiatry have largely investigated Mediterranean-style diets. However, there are other diets with supporting preclinical or preliminary clinical data to support their use that require further investigation in rigorous, sufficiently powered trials. An example of this is the ketogenic diet, of which there are several case-reports, observational studies, and preclinical data suggesting a therapeutic effect in psychiatric conditions; however, there are currently no published RCT to confirm efficacy(Reference Dietch, Kerr-Gaffney and Hockey26). The same is true of other diet patterns that share principles similar to the Mediterranean diet that could have mental health utility in other cultural settings(Reference George, Kucianski and Mayr77). Other promising dietary approaches include high-polyphenol dietary interventions and dietary interventions that promote reduction in ultra-processed foods(Reference Lane, Gamage and Travica6,Reference Gamage, Orr and Travica78) .

Scalable interventions and implementation research

While the trial evidence for the efficacy of nutraceutical and dietary interventions continues to grow, there is currently limited evidence regarding the effectiveness and implementation feasibility of nutraceutical and dietary interventions. We encourage further research that investigates the implementation of Nutritional Psychiatry into the real-world mental health care settings. These data will be invaluable in informing policy and will provide evidence-based models of how Nutritional Psychiatry can be integrated into clinical settings with the appropriate funding mechanisms to support implementation. Related to this is the need to investigate scalable approaches to dietary interventions. Online/telehealth delivery and group-based interventions are examples of scalable models of delivery that have facilitated the integration of other lifestyle interventions (e.g. exercise) into national clinical guidelines(79) but workforce, education, and funding are issues that require consideration.

Explore psychosocial outcomes

While much of the existing literature in Nutritional Psychiatry has focused on the potential biological mechanisms of dietary interventions to improve mental health, the possible psychosocial mechanisms have received less attention. Similar to exercise interventions, where the role of exercise in improving self-esteem, self-efficacy, and social support networks has been investigated as a potential psychosocial mechanism of action(Reference Kandola, Ashdown-Franks and Hendrikse80), such investigations can be informative to future study designs and inform barriers and enablers to treatment response. Some studies have assessed factors such as self-efficacy and self-worth as secondary outcomes(Reference Jacka, O’Neil and Opie12,Reference Parletta, Zarnowiecki and Cho13) ; however, further research is required to assess these and additional psychosocial factors as potential drivers underlying clinical efficacy of diet and nutraceutical interventions.

Conclusion

To assist continued research in the field of Nutritional Psychiatry, the ISNPR provides the first set of guidelines on clinical trial, design, conduct, and reporting for future clinical trials in this area. The sixty-one included recommendations cover several aspects of clinical trial design and reporting. The importance of a multidisciplinary research team and patient-centred input is a common theme. Recommendations also emphasise recognising and addressing unique biases in nutrition trials, improving the transparency and replicability of trial reporting, and calls for research into diverse populations and mental disorders. Recommendations included within these guidelines are intended to improve the rigor, impact, and clinical relevance of ongoing and future trials in Nutritional Psychiatry.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114524001946

Acknowledgements

W. M. is currently funded by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (#2008971). W. M. has previously received funding from the Cancer Council Queensland and university grants/fellowships from La Trobe University, Deakin University, University of Queensland and Bond University. W. M. has received funding and/or has attended events funded by Cobram Estate Pty. Ltd and Bega Dairy and Drinks Pty Ltd. W. M. has received travel funding from Nutrition Society of Australia. W. M. has received consultancy funding from Nutrition Research Australia and ParachuteBH. W. M. has received speakers honoraria from The Cancer Council Queensland and the Princess Alexandra Research Foundation.

Conceptualization, W. M. and H. M. S.; Methodology, W. M. and H. M. S.; Formal Analysis, W. M. and H. M. S. Investigation, W. M., M. J., C. W., F. N. J., J. B., H. F., R. O., M. H., S. B. T., A. S. V., A. O., K.-P. S., J. R., M. B., A. L., D. M., J. J., and H. M. S.; Writing – Original Draft, W. M. and H. M. S.; Writing – Review & Editing, W. M. and H. M. S. Investigation, W. M., M. J., C. W., F. N. J., J. B., H. F., R. O., M. H., S. B. T., A. S. V., A. O., K.-P. S., J. R., M. B., A. L., D. M., J. J., and H. M. S.; Visualization, W. M.

M. B. is supported by a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship and Leadership 3 Investigator grant (1156072 and 2017131). A. O. is supported by National Health & Medical Research Council Emerging Leader 2 Fellowship (2009295). S. T. is supported by a National Health & Medical Research Council Emerging Leader 1 Fellowship (2017302). D. M. has received research support from Nordic Naturals and Heckel Medizintechnik GmbH. He has received honoraria for speaking from the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy, Peerpoint Medical Education Institute, LLC and Harvard blog. He also works with the MGH Clinical Trials Network and Institute (CTNI), which has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies and NIMH. K.-P.S. has been a speaker and/or consultant for Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, Lundbeck, Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, Servier, Otsuka, Excelsior Biopharma, Chen Hua Biotech, Nutrarex Biotech and Hoan Pharmaceuticals. H. M. S. is currently funded by a National Health & Meical Research Council Emerging Leader Fellowship (2018118) and has received research funding from DSM Pharmaceuticals and VSL Pharmaceuticals, non-financial support from VSL Pharmaceuticals, consulting fees from Dietitian Connection, Dietitians Australia and Microba. A. L. is the managing director of Clinical Research Australia, a contract research organisation and has completed several industry-sponsored clinical trials on phytoceuticals and nutritional ingredients. He has received either presentation honoraria or clinical trial grants from Arjuna Natural Ltd, Dolcas-Biotech LLC, Blackmores Limited, Pharmactive Biotech Products SL, Ixoreal Biomed, Metagenics Australia, EuroPharma Inc, Bio-gen Extracts Pvt Ltd, Natural Remedies Pty Ltd, Verdure Sciences Inc, Sabinsa Corporation, Bio-Practica and Activ’Inside. F. N. J. is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (#1194982). She has received: (1) competitive Grant/Research support from the Brain and Behaviour Research Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Rotary Health, the Geelong Medical Research Foundation, the Ian Potter Foundation, The University of Melbourne; (2) industry support for research from Meat and Livestock Australia, Woolworths Limited, the A2 Milk Company, Be Fit Foods, Bega Cheese; (3) philanthropic support from the Fernwood Foundation, Wilson Foundation, the JTM Foundation, the Serp Hills Foundation, the Roberts Family Foundation, the Waterloo Foundation and (4) travel support and speakers honoraria from Sanofi-Synthelabo, Janssen Cilag, Servier, Pfizer, Network Nutrition, Angelini Farmaceutica, Eli Lilly, Metagenics and The Beauty Chef. She is on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Dauten Family Centre for Bipolar Treatment Innovation and Zoe Limited. F. N. J. has written two books for commercial publication. J. M. J. is currently funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) K23 AT012068. J. M. J. and J. J. R. have received active and placebo product for clinical trials without cost from Hardy Nutritionals, TrueHope and Renova; however, none of the companies have been involved in the data collection, analysis, write up or publication of resulting data.