Healthy dietary habits, starting early in life, are the foundation for good nutrition, health and development during childhood and beyond. School food programmes or school feeding programmes (SFP) are receiving increasing attention as important drivers of healthy eating and academic performance. Therefore, multiple policies have been adopted in different places to offer food and meals to students.

There is intense debate between policymakers and government SFP that should be universal v. targeted for those who need it(Reference Morelli and Seaman1–Reference Cohen, Verguet and Giyose3). In different countries, such as England and the USA, the debate intensified during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic(Reference Bean, Adams and Buscemi4,Reference Taylor5) . Although most studies reached their conclusions based on assessments of more than one dimension of the SFP, such as academic performance, equity, acceptability and food supply, this was still not enough to convince policymakers of the importance of free meals for all students(Reference Cohen, Verguet and Giyose3,6) .

Many countries provide free school meals in disadvantaged regions or for students from low-income families, while charging for meals for other students. These SFP are generally more focused on primary and public schools and offer meals, and more than 90 % aim to meet nutritional and/or health targets. In school meals, prepared at school is the most common modality of food delivery (80 % of countries)(7).

The school food environment is known to present a strategic opportunity to improve children’s dietary intake on a large scale by offering free meals that are accessible to all students(Reference de Oliveira Cardozo, Crisp and Fernandes8). This can be part of the educational process and drive important changes in the food system, in addition to what SFP reach children and adolescents at a population scale across socio-economic classes and for over a decade of their lives(Reference Oostindjer, Aschemann-Witzel and Wang9). From this perspective, we present evidence of the benefits of a universal SFP and ways to regulate these programmes.

The view from the global south

A small number of countries offer SFP with free meals for all students, usually developed countries with small populations or limited territorial extensions. For this reason, we decided to analyse Brazil and India’s programmes, as they are the seventh and first countries in the world in terms of population, respectively, and have the two of the most comprehensive-free SFP for all students, based on federal legislation that establishes criteria for the provision of school meals(Reference Cohen, Verguet and Giyose3,7) .

The case of Brazil

Brazil has one of the largest SFP in the world, the Brazilian School Food Programme (Programa Nacional de Alimentação Escolar, PNAE), with universal access and offers at least one free meal during students’ stay at school. Originating in the 1950s, the PNAE provided meals with strong and time-to-time updated nutrition guidelines that prioritise the offer of fresh or minimally processed foods and meals based on them and limits ultra-processed foods to guarantee healthy meals for students(Reference Canella, Bandeira and de Oliveira10). The programme provided at least 20 % of the nutritional needs of part-time students(Reference Canella, Bandeira and de Oliveira10).

The PNAE is the only programme that guarantees free meals for all levels of education, from kindergarten to high school (basic education), in Brazilian public schools (corresponding to 80 % of the students enrolled). In addition, at least 30 % of the federal budget is used to purchase food from family farms. In 2015, PNAE purchases from family farming contributed nearly 457 million USD(Reference Berchin, Nunes and de Amorim11).

Recent evidence suggests a positive impact on students’ diets. PNAE positively affects the overall quality of diet, increases the consumption of food indicators of healthy eating habits and decreases the consumption of unhealthy food indicators(Reference Locatelli, Canella and Bandoni12).

A study that compared the diet of adolescents who attended schools without food offered by the PNAE (private school) with those who provided meals by the PNAE (public schools) showed that Brazilian adolescents in schools without PNAE were more likely to consume regular (≥5 times/week) ultra-processed salty foods and soft drink(Reference Noll, Noll and de Abreu13). Furthermore, children who consumed two or three school meals daily showed a higher consumption of fresh and minimally processed food and a significant decrease in ultra-processed food compared with students who did not consume school meals(Reference Bento, Moreira and Carmo14).

Two studies with representative samples of Brazilian children and adolescents demonstrated that eating meals offered by public schools improved the nutritional status of Brazilian children(Reference Bandoni and Canella15,Reference Boklis-Berer, Rauber and Azeredo16) . Adolescents with high adherence to school meals (5 times/week) had a 0·10 lower BMI Z-score, 11 % lower prevalence of overweight and 24 % lower prevalence of obesity than those with lower adherence(Reference Boklis-Berer, Rauber and Azeredo16).

The case of India

India is the second most populous country in the world, and the mid-day meal (MDM) programme is the largest SFP in the world, covering over 100 million children. MDM provides a free cooked meal with a minimum energy content of 450 kcal and 12 g of protein to children in government and government-assisted primary schools and 700 energy content and 20 g of protein/d per student for upper primary schools. The programme aims to improve school attendance and retention and the nutritional status of primary school children(Reference Ramachandran17). In addition, MDM recommends the provision of adequate amounts of micronutrients such as Fe, folic acid and Zn to complement school health and other health programmes(Reference Ali and Akbar18).

MDM exposure for nearly 5 years in primary school increased test scores by 18 % for reading and 9 % for math, relative to children with less than a year of exposure, showing a positive effect on learning achievement(Reference Chakraborty and Jayaraman19). The programme had a large effect on net enrolment, which increased by 16–19 %, and the effect was larger for socially disadvantaged groups(Reference Chakraborty and Jayaraman19).

There are few papers on the impact of MDM on the nutritional status and food consumption of primary school students. A study that investigated the intergenerational nutritional benefits of the programme found that investments made in school meals in previous decades were associated with improvements in future child linear growth, and the MDM was associated with 13–32 % of the eight-for-age Z-score improvement in India from 2006 to 2016(Reference Chakrabarti, Scott and Alderman20).

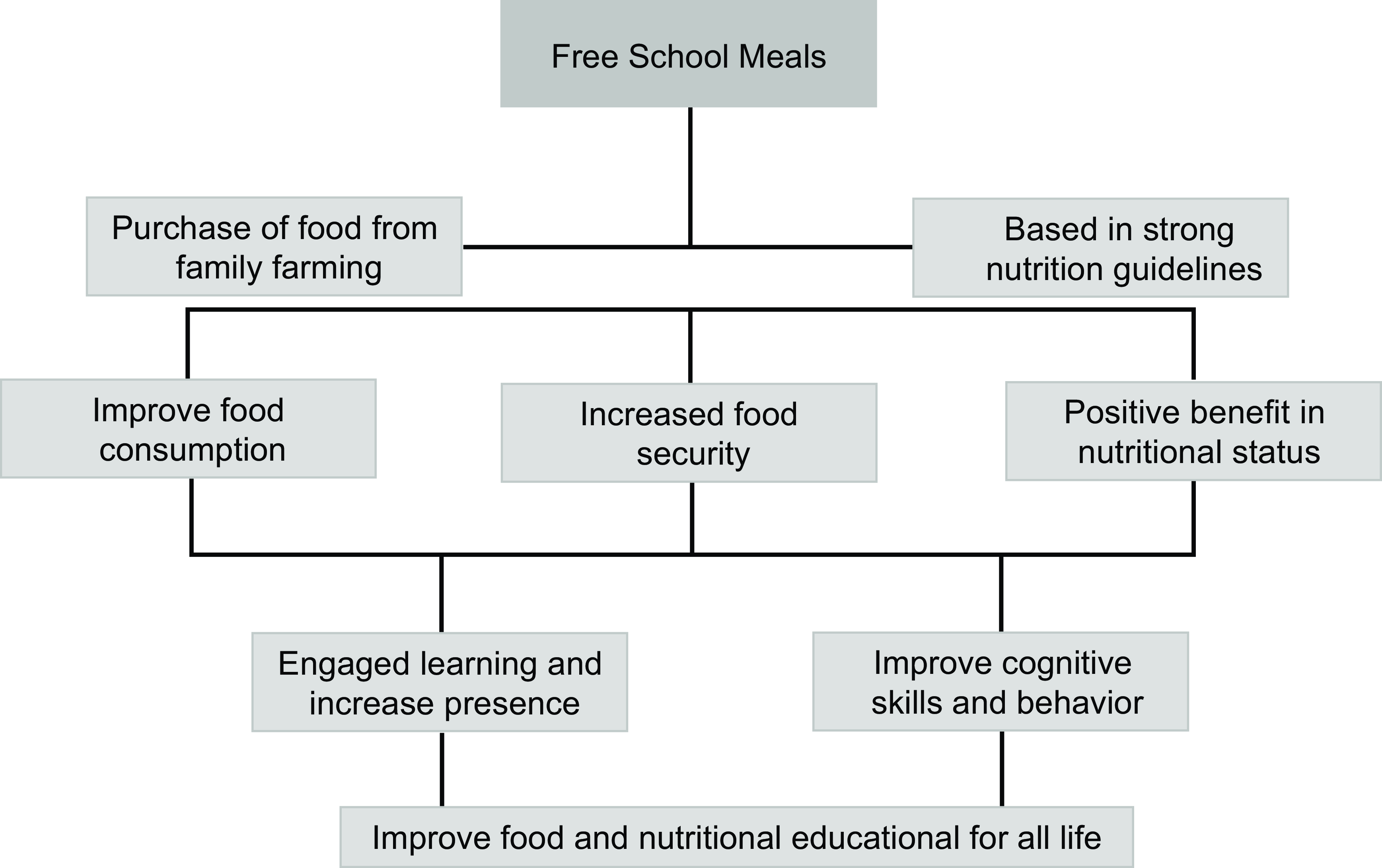

In this context, a theoretical framework was developed to summarise the evidence for the benefits of free school meals (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Conceptual framework of the benefits of free school meals.

School feeding programme promotes sustainable feeding and food and nutrition education

Among other food and nutrition policies, the SFP is noteworthy for its sustainable potential and for promoting food and nutrition education. Climate change has placed the sustainability of the global food system and its contributions to feeding the world’s population at the centre of debate(Reference Rosenzweig, Mbow and Barioni21). SFP have emerged as important contributors to the development of sustainable food systems, which can change the relationship between future generations and food and the environment(Reference Oostindjer, Aschemann-Witzel and Wang9) if they reach all students.

In this context, the following aspects stand out: SFP to be state led gives it reach, legitimacy and implementation capacity, and its reach populations are at risk of food insecurity and malnutrition in all forms (undernutrition and obesity), which is why it is important to implement a universal policy. Lastly, SFP is a systemic (instead of segmental) food supply chain that allows structural changes throughout the entirety of the food system, which contributes to the food security of both the producer and the consumer, who is the student(Reference Ashe and Sonnino22).

SFP designed to consider the food source, with the addition of a local supply component, have the potential to benefit entire communities by stimulating local markets and family farmers, facilitating agricultural changes and enabling households to invest in productive assets(7,Reference Berchin, Nunes and de Amorim11) .

Thus, sustainable SFP development is possible, regardless of the size of the state or country. The mandatory purchase of family farming or a popular and solidarity economy through laws is a strategy that not only supports family farming by connecting farmers with a secured market with pre-negotiated prices but also increases the amount of local and fresh products available in school menus(Reference Batistela dos Santos, da Costa Maynard and Zandonadi23). Different Latin American countries, such as Ecuador, Guatemala and Honduras, have included the obligation to buy food locally in their SFP, encouraging family farmers and the poor and vulnerable sectors of the population(24).

A systematic review verified the recommendations on sustainability in school feeding policies and practices adopted in schools and found that recommendations for purchasing sustainable food (organic, local and seasonal), nutrition education focused on sustainability and food waste reduction were frequent(Reference Batistela dos Santos, da Costa Maynard and Zandonadi23). The relationship between sustainability and the SFP also occurs at the decision level at all stages of meal production, including menus.

Although the SFP predisposes to sustainability, it is essential to have regulations that guide and encourage sustainable and interdisciplinary practices.

Food practices are influenced by many biological, social, psychological and environmental factors(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino25,Reference Cruwys, Bevelander and Hermans26) . Knowledge about food is only part of the reason for eating choices(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino25), and experiences with food play an important role as humans come to like food through associative conditioning, both physiologically and socially(Reference Monterrosa, Frongillo and Drewnowski27). Repeated exposure to healthy foods leads to increased familiarity and acceptance(Reference Scaglioni, Arrizza and Vecchi28). Food choice is also subject to availability, affordability and accessibility, as one can only choose between what is available, financial and physically accessible(Reference Contento29). Thus, school meals are an inherent part of food and nutrition education as they promote exposure to and access to healthy food, providing opportunities to practice and experience what is learned in the classroom.

The efficacy of nutritional education interventions also depends on environmental factors. Longer interventions with focused goals, involving teachers and offering environmental opportunities to practice content leant in theoretical classes were found to be more effective(Reference Murimi, Kanyi and Mupfudze30,Reference Cotton, Dudley and Peralta31) . As food choice is heavily determined by food availability, offering healthy free school meals along with educational and theoretical approaches in the classroom can lead to changes in eating practices(6).

Food and nutrition education is the key strategy to promote food security, work to overcome inequalities and advocate for the Human Right to Adequate Food, recognising that good nutrition is the foundation for human health, well-being and physical and cognitive development(32). Since food and nutrition security is central to individual dignity and human rights, Brazil has included in its constitution the Human Right to Adequate Food and the right to school meals for all students in basic education. This is important to create the necessary foundation for the development of public policies for sustainable food systems(Reference Ayala and Meier33,Reference Ottoni, De Oliveira and Bandoni34) .

Why free meals at school?

Children spend a considerable part of their day at school, and offering free meals for everyone can be a great tool for learning about food, eating and achieving food and nutrition security(Reference de Amorim, Dalio dos Santos and Ribeiro Junior35).

Eating habits develop at an early age, and healthy eating habits formed during childhood are more likely to persist throughout life(Reference Scaglioni, Arrizza and Vecchi28). The SFP can offer not only healthy meals but also opportunities for food and nutrition education that represents a huge opportunity for children and adolescents to learn about healthy and sustainable food practices(Reference Oostindjer, Aschemann-Witzel and Wang9).

Evidence from the two largest SFP in the world that offer free meals for all students shows that policies can improve targeted dietary intake(Reference Locatelli, Canella and Bandoni12), nutritional status(Reference Bandoni and Canella15,Reference Boklis-Berer, Rauber and Azeredo16) , learning achievement(Reference Ramachandran17) and school permanence(Reference Ramachandran17,Reference Kaur36) . These findings highlight the positive impact of universal free meals on schools.

The Brazilian PNAE is an important case because it changes the concept that SFP in middle- and low-income countries only aim to alleviate food insecurity and implement nutritional guidelines to develop healthier eating habits to establish positive dietary habits for the future(Reference Canella, Bandeira and de Oliveira10,Reference Aliyar, Gelli and Hamdani37) .

A systematic review that examined universal free school meals found that offering at least one lunch per day to students was positively associated with diet quality, food and nutrition security and academic performance; however, when the offer was restricted to free breakfast, the effect was uncertain(Reference Cohen, Hecht and McLoughlin2). Furthermore, no studies have considered the cost of maintaining large databases, usually based on family income, updated regularly to determine which students are eligible to receive free school meals and the social implications of creating paying and non-paying groups of students(Reference Cohen, Hecht and McLoughlin2).

The major challenge in implementing free school meals is creating SFP guidelines to meet each country’s nutritional needs, food culture and ensure the provision of healthy foods in schools.

The COVID-19 pandemic has generated a new food insecurity crisis(Reference Pryor and Dietz38), increasing global hunger by 120 million, and it is estimated that between 690 and 783 million people worldwide have faced hunger(39). During the pandemic in most countries, schools were closed, but SFP responded actively and often with great agility to a crisis, temporarily changing their modality of providing food to students and helping to ensure food security for families and communities(7). Therefore, we argue that the SFP can make a significant contribution to the definition of a resilient food system that enables, promotes and enhances well-being. Now is the ideal moment for international organisations, such as the FAO and WHO, to recommend the adoption of a universal SFP.

Conclusion

Schools are levers for social change, and students must eat while in school. Thus, a positive meal experience can be created in this environment.

The world faces severe public health consequences from our current food system, facing different kinds of malnutrition and ecological destruction, so it is important for all students to receive food and nutrition education (such as food gardening and cooking at school) and receive healthy and socially referenced meals in school (e.g. using foods from family farmers, which considers the local cultural aspects). As students get older, they will understand the consequences of food supply. The implementation of free SFP can greatly enhance and improve the quality of life of millions of children and adolescents worldwide.

These are extraordinary times, the world facing major global challenges, the search for political consensus cannot keep us from proposing solutions that can effectively support major changes in our food system. Currently, it is time to offer healthy and free meals in schools for everyone to contribute to the dietary quality and health of children and adolescents, sustainable healthy food systems and the planet.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Veridiana Vera de Rosso for their helpful suggestions, which contributed to this work.

This research received no specific grants from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

The contribution made by D. H. B. was that of the lead researcher and conceptualised the paper responsible for the final version of the manuscript. I. C. O. and A. L. B.A. wrote and edited the manuscript. D. S. C. wrote and reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.