Swine dysentery (SD) is a contagious mucohaemorrhagic diarrhoeal disease that mainly occurs in pigs in the grower/finisher phase. The essential causative agent of SD is the anaerobic intestinal spirochaete Brachyspira hyodysenteriae, and this pathogen acts in association with other anaerobic members of the large-intestinal microbiota to induce extensive inflammation and necrosis of the epithelial surface of the caecum and colon(Reference Hampson, Fellström, Thomson, Straw, Zimmerman, D'Allaire and Taylor1). It is known that the pigs' diet can have a strong influence on colonisation by B. hyodysenteriae and on the occurrence of clinical signs of SD. Several studies have been undertaken to elucidate the effects of different types of carbohydrates on colonisation with B. hyodysenteriae and on the incidence of SD, but the results have been contradictory(Reference Kirkwood, Huang and McFall2–Reference Siba, Pethick and Hampson5). Recently, a diet containing chicory root and sweet lupin was shown to offer protection against SD(Reference Thomsen, Bach Knudsen and Jensen6), and subsequently we demonstrated that feeding pigs 80 g/kg inulin but not lupin prevented SD following experimental challenge with B. hyodysenteriae (Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7). Inulin is a mildly sweet, white polysaccharide that is normally extracted from chicory root.

Physiologically, fructo-oligosaccharides such as inulin are classified as dietary fibre and are resistant to complete enzymatic degradation in the small intestine. Undigested fibre entering the caecum and colon functions as a substrate for fermentative processes and generates a higher luminal concentration of volatile fatty acids (VFA), which in turn can cause lower luminal pH values(Reference Jensen and Jørgensen8). Inulin is mainly fermented in the large intestine to VFA, lactate and gas by Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli species(Reference Roberfroid, Van Loo and Gibson9). In addition, dietary inulin supplementation may regulate metabolic activity, decreasing the protein:carbohydrate ratio in the hindgut. As a result, carbohydrate fermentation may suppress the formation of branched-chain fatty acids (BCFA) and NH3 produced from protein fermentation(Reference Macfarlane and Macfarlane10).

Dietary supplementation with inulin is expensive, and currently no information is available concerning the level of dietary inulin inclusion that is necessary to reduce the occurrence of SD and cause changes in the microbiota in the large intestine of pigs. Accordingly, the present study was designed to determine whether dietary inclusion of less than 80 g/kg inulin could prevent pigs that were experimentally challenged with B. hyodysenteriae from developing the disease. The hypothesis tested was that a diet supplemented with 80 g/kg inulin would decrease the risk of pigs developing SD and reduce protein fermentation in the hindgut.

Materials and methods

The present study was conducted with the approval of the Murdoch University Animal Ethics Committee (R2186-08). Animals were cared for according to the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes(11).

Animals and housing

A total of sixty surgically castrated commercial pigs (Large White × Landrace) were obtained at weaning from a commercial specific-pathogen-free piggery known to be free of SD. At weaning, the pigs were housed in a group at Murdoch University and were offered the same commercially formulated diets without any feed additives or antimicrobial compounds until they reached a body weight of 31·2 (sd 4·28) kg. At this time, the pigs were allocated to one of the four experimental diets based on their body weight. The pigs were housed in a temperature-controlled animal house in three identical rooms. Each room had four pens in a square arrangement so that each pen was adjacent to two other pens. The pens were raised above the ground and had fully slatted plastic floors and wire mesh sides that allowed contact between the animals and passage of manure between the pens. In each room, there was one pen of five pigs per experimental diet (i.e. there were fifteen pigs per experimental diet). Each pen was equipped with a dry-feed single space feeder without water and two drinking bowls. Throughout the study, the pigs had ad libitum access to feed and water. Group housing was chosen to facilitate transmission of the pathogenic bacteria within and between groups(Reference Pluske, Durmic and Pethick4, Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7, Reference Pluske, Siba and Pethick12). The pigs were allowed to adapt to the diets for 2 weeks before being challenged with B. hyodysenteriae.

Experimental design and diets

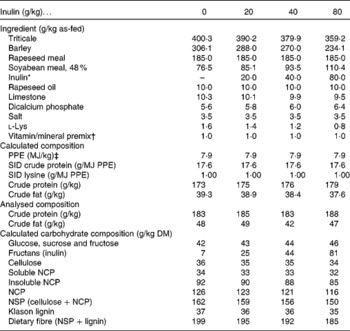

The experimental design was a completely randomised block arrangement, with four dietary treatments differing in the amount of added dietary inulin (0, 20, 40 and 80 g/kg). The four diets were formulated, as shown in Table 1, to meet or exceed the nutrient requirements for pigs of this genotype, and all diets contained the same energy and protein (amino acids) contents. Inulin (Orafti®ST; Orafti, Tienen, Belgium) was added to the diets at the expense of triticale and barley. The diets were produced in mash form using the same batch of raw materials and did not contain any antimicrobials.

Table 1 Diet ingredients and chemical composition of the experimental diets

PPE, potential physiological energy; SID, standardised ileal digestible; NCP, non-cellulosic polysaccharides.

* Orafti®ST, Orafti, Tienen, Belgium.

† Supplied/kg of diet: Fe (FeSO4), 60·0 mg; Cu (CuSO4), 10·0 mg; Mn (MnO), 40·0 mg; Zn (ZnO), 100·0 mg; Se (Na2SeO3), 0·30 mg; I (KI), 0·50 mg; Co (CoSO4), 0·20 mg; vitamin A, 7000 IU (2100 μg); vitamin D3, 1400 IU (35 μg); vitamin E, 20·0 mg; vitamin K3, 1·0 mg; thiamin, 1·0 mg; riboflavin, 3·0 mg; pyridoxine, 1·5 mg; vitamin B12, 0·015 mg; pantothenic acid, 10·0 mg; folic acid, 0·2 mg; niacin, 12·0 mg; biotin, 0·03 mg.

‡ Potential physiological energy(Reference Boisen35).

Challenge with Brachyspira hyodysenteriae and assessment of swine dysentery

Australian B. hyodysenteriae strains WA1 and B/Q02 were obtained as frozen stocks from the culture collection at the Reference Centre for Intestinal Spirochaetes, Murdoch University. They were thawed and grown in Kunkle's pre-reduced anaerobic broth containing 2 % (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1 % (v/v) ethanolic cholesterol solution(Reference Kunkle, Harris and Kinyon13), and were incubated at 37°C on a rocking platform until early log-phase growth was achieved.

Each morning for four consecutive days, all pigs were challenged via a stomach tube with 100 ml broth culture containing approximately 109 colony-forming units/ml of B. hyodysenteriae, made up of equal numbers of each of the two spirochaete strains. At this time, the pigs had an average body weight of 41·1 (sd 4·47) kg.

The pigs were weighed weekly, and rectal swabs were taken from all pigs twice a week for spirochaete culture. Visual faecal consistency scoring (1, firm, well formed; 2, soft; 3, loose; 4, watery; 5, watery with mucus/blood) was conducted daily. Watery diarrhoea with mucus/blood was considered as indicating SD, and pigs showing these signs were removed for post-mortem examination within 48 h. All other pigs were removed for necropsy 42 d after the first day of challenge.

Post-mortem

Euthanasia was by captive bolt stunning followed by exsanguination. The gastrointestinal tract was removed immediately and divided into seven segments by ligatures: stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, caecum, upper colon and lower colon. The presence, distribution and nature of gross lesions in the large intestine were recorded(Reference La, Phillips and Reichel14), and bacteriological swabs were taken from the wall of the caecum and proximal colon for spirochaetal culture. The luminal contents were then removed by gently squeezing the material from the gut segment. The empty segments and collected material were weighed, and representative samples were collected in sterile plastic tubes that were snap-frozen in liquid N2 within 10 min of euthanasia. Samples for DM and VFA examination were stored at − 20°C until analysis.

For determination of NH3 nitrogen (N-NH3), digesta samples were diluted 1:1 (w/v) with TCA (10 %), mixed, snap-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at − 80°C until analysis. The pH values of the digesta were measured by inserting the electrode of a calibrated portable pH meter (Schindengen pH Boy-2; Schindengen Electric MFG, Tokyo, Japan) into the collected sample. The DM content of samples was measured using the AOAC method (930.15)(15).

Histological measurements

A ring-like cross-section of the ileum was collected and immediately fixed in 10 % neutral-buffered formalin. Measurements of villous height and crypt depth were conducted as described by Hansen et al. (Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7).

Bacteriological analysis

Bacteriological swabs taken from faeces, caecum and colon were streaked onto selective agar plates designed for isolation of Brachyspira species(Reference Jenkinson and Wingar16), consisting of Trypticase Soya agar (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, MD, USA) containing 5 % (v/v) defibrinated sheep blood, spectinomycin (400 μg/ml), and colistin and vancomycin (each 25 μg/ml) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The plates were incubated for 5–7 d at 37°C in a jar with an anaerobic environment generated using a GasPak Plus disposable H2+CO2 generator envelope with a Pd catalyst (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The presence of low, flat, spreading growth of spirochaetes on the plate and any haemolysis around the growth were recorded. Spirochaetes were confirmed by selecting areas of suspected growth, resuspending in PBS and examining the suspension under a phase-contrast microscope at 400 × magnification. Spirochaetes were identified as B. hyodysenteriae on the basis of strong β-haemolysis, microscopic morphology and PCR results of an NADH oxidase gene for cell growth on the plates. The PCR primers and conditions have been described previously(Reference La, Phillips and Hampson17).

Analysis of feed, organic acids and ammonia nitrogen

The N content of the feed was determined with a N analyser (LECO FP-428; LECO Corporation, St Joseph, MI, USA) by a combustion method (American Organization of Analytical Chemists 990.03)(15). Crude protein was calculated by multiplying the N content by 6·25. Crude fat was measured using the AOAC Soxhlet method (960.39)(15).

The concentrations of organic acids (formic acid, VFA, lactic acid and succinic acid) in the ileal contents were analysed by the method described by Jensen et al. (Reference Jensen, Cox and Jensen18). The VFA concentrations in caecal and colon contents were determined as described by Heo et al. (Reference Heo, Kim and Hansen19).

Concentrations of N-NH3 were measured according to the method by Weatherburn(Reference Weatherburn20). Briefly, the supernatant was deproteinised using 10 % TCA. NH3 and phenol were oxidised by sodium hypochlorite in the presence of sodium nitroprusside to form a blue complex. The intensity was measured colorimetrically at a wavelength of 623 nm. Intensity of the blue colour is proportional to the concentration of NH3 present in the sample.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA), with each pig regarded as the experimental unit, given that each pig was challenged. A binary response was recorded for each pig with respect to colonisation with B. hyodysenteriae. Data were analysed with a logistic regression model using the GENMOD procedure in SAS, with the effect of inulin and room as fixed effects. The Pearson χ2 correction (pscale) was applied to correct for overdispersion.

The effect of inulin inclusion on the various quantitative variables measured was analysed univariately by the generalised linear model (GLM) procedure of SAS, with room and dietary inulin level included in the model. Polynomial regression was used to determine the presence of linear or quadratic treatment effects as inulin levels were increased. Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) between digesta pH and concentrations of VFA were calculated using the CORR procedure. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0·05, and P < 0·10 was considered a trend.

Results

Overall, there was a good general correspondence between the expected and analysed contents of nutrients in the experimental diets (Table 1).

Incidence of swine dysentery and re-isolation of Brachyspira hyodysenteriae

The incidence of SD and isolation of B. hyodysenteriae from faeces and colonic digesta are shown in Table 2. Pigs fed 0, 20 and 40 g/kg inulin generally had a greater risk (P = 0·002) of developing SD and were more likely (P < 0·001) to have colonic contents that were culture positive for B. hyodysenteriae at kill compared with pigs receiving 80 g/kg inulin. Although pigs fed 80 g/kg inulin were less likely to have faecal samples that were culture positive for B. hyodysenteriae during the experimental period, eight out of fifteen did develop the disease.

Table 2 Number of positive pigs and relative risk* of a pig being culture positive for Brachyspira hyodysenteriae or showing clinical signs of swine dysentery (fifteen pigs per dietary treatment)

* The risk of an event in the group of interest compared with the reference group.

DM, pH and ammonia nitrogen

The DM content in the caecum decreased linearly (P = 0·007) with increasing dietary inulin levels (Table 3). The opposite occurred in the lower colon, with the DM content increasing linearly (P = 0·007) with increasing inulin levels. The DM content in the ileum and upper colon were not influenced by diet.

Table 3 DM, pH and NH3 nitrogen (N-NH3) concentration in digesta from different segments of the gastrointestinal tract at the day of euthanasia in pigs fed diets containing inulin and experimentally challenged with Brachyspira hyodysenteriae

(Mean values and pooled standard errors, fifteen pigs per dietary treatment)

a,b Mean values with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0·05).

The pH values in the caecum tended to decrease (P = 0·072) and in the upper colon decreased (P = 0·047) linearly with inulin levels in the diets. In the ileum and lower colon, the pH values were not influenced by diet. N-NH3 concentrations in the caecum, upper colon and lower colon were unaffected by dietary inulin levels (Table 3).

Organic acids in digesta

Diet did not affect the total concentration of organic acids or the molar proportion of the organic acids in the ileum, except for a tendency towards a linear decrease in the proportion of propionic acid (P = 0·060; Table 4). On the other hand, a linear increase in total VFA concentration was observed in the caecum (P = 0·018), upper colon (P = 0·001) and lower colon (P = 0·013). In the caecum, increasing dietary inulin tended to linearly increase the molar proportion of propionic acid (P = 0·067), whereas a linear reduction in the percentage of isobutyric acid (P = 0·015) and isovaleric acid (P = 0·026) was observed. In the upper colon, there was a linear decrease, or there tended to be a decrease, in the percentage of acetic acid (P = 0·065), isobutyric acid (P = 0·011) and isovaleric acid (P = 0·013) with increasing levels of dietary inulin. In contrast, an increase or tendency towards a linear increase was found for propionic acid (P = 0·038), butyric acid (P = 0·070) and valeric acid (P = 0·007). In the upper colon, there was a linear increase in the percentage of butyric acid (P = 0·026), valeric acid (P = 0·005) and caproic acid (P = 0·051), but a tendency towards a linear decrease in the proportion of isobutyric acid (P = 0·056).

Table 4 Total volatile fatty acid (VFA) concentration (mmol/kg of digesta) and molar proportion of the organic acids in digesta from different segments of the gastrointestinal tract at the day of euthanasia in pigs fed diets containing inulin and experimentally challenged with Brachyspira hyodysenteriae

(Mean values and pooled standard errors, fifteen pigs per dietary treatment)

a,b Mean values with unlike superscript letters were significantly different (P < 0·05).

* Sum of butyric, valeric, caproic, isobutyric, isovaleric and succinic acid.

Overall, total VFA concentrations and pH in digesta were negatively correlated in the ileum (Pearson's r = − 0·29; P = 0·039), caecum (Pearson's r = − 0·55; P < 0·001), upper colon (Pearson's r = − 0·69; P < 0·001) and lower colon (Pearson's r = − 0·58; P < 0·001).

Ileal histology and pig performance

Ileal villus height, crypt depth and the villus:crypt ratio were unaffected by the dietary treatments (data not shown). Average daily gain did not differ in the 2-week adaptation period before pigs were challenged with B. hyodysenteriae. The pigs fed diets containing 0, 20, 40 and 80 g/kg inulin grew on average 660 (sem 43·0), 753 (sem 46·8), 752 (sem 45·1) and 661 (sem 43·4) g/d, respectively. Overall, pig performance was unaffected by the dietary inclusion rates of inulin.

Discussion

The model of SD used in the present study was effective, as all fifteen pigs fed the control diet developed disease. In this setting, 80 g/kg dietary inulin inhibited the development of SD, confirming our previous findings(Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7). However, lower concentrations of inulin were not protective, demonstrating that a high concentration of dietary inulin is required for protection if it is used as the sole intervention. In the present study, more than half of the pigs (eight out of fifteen pigs) fed 80 g/kg inulin developed the disease, whereas disease occurred only in 15 % of the pigs (three out of twenty pigs) receiving this concentration of inulin in our previous study(Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7). This difference might be explained by the amount and concentration of the broth used to challenge the pigs: in the present study, the pigs were challenged on four consecutive days with 100 ml of a broth containing approximately 109 colony-forming units/ml of B. hyodysenteriae compared with 80 ml of a broth culture with approximately 108 colony-forming units/ml viable cells in the previous study(Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7). With this regard, a higher level of infectious challenge may have overwhelmed the protection afforded by the inulin.

Nonetheless, the present findings are in accordance with other researchers who also found that fermentable dietary carbohydrates reduced the incidence of SD(Reference Thomsen, Bach Knudsen and Jensen6, Reference Bilic and Bilkei21). In a field study, Bilic & Bilkie(Reference Bilic and Bilkei21) observed that a diet with wheat shorts and maize starch reduced the incidence of SD but, as in the present study, total protection against SD was not achieved. In contrast, Thomsen et al. (Reference Thomsen, Bach Knudsen and Jensen6) found that an organic diet based on dried chicory roots and lupins completely protected pigs against SD after experimental challenge with B. hyodysenteriae. In our previous study, we demonstrated that pigs fed 80 g/kg inulin had a reduced risk of developing SD, while the onset of disease was delayed in pigs fed lupins(Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7); however, unlike Thomsen et al. (Reference Thomsen, Bach Knudsen and Jensen6), it was found that a small number of pigs fed the various ‘protective’ diets developed the disease. These discrepancies are most probably due to differences in virulence of the different strains of B. hyodysenteriae employed or differences in the experimental diets used.

In contrast, feeding fermentable carbohydrates from sugarbeet pulp, wheat shorts and potato starch failed to prevent the development of SD(Reference Kirkwood, Huang and McFall2), while feeding diets that contained wheat, barley or oat groats resulted in an almost 100 % incidence of SD(Reference Pluske, Siba and Pethick12). This demonstrates that the amount and properties of the dietary carbohydrates are important considerations when formulating diets to control infections with B. hyodysenteriae.

The present findings seemingly contradict previous findings, where diets supplemented with soluble NSP and resistant starch were associated with the development of SD compared with diets based on cooked white rice and animal proteins(Reference Pluske, Durmic and Pethick4, Reference Siba, Pethick and Hampson5, Reference Pluske, Siba and Pethick12). On the other hand, attempts to reproduce these results by Lindecrona et al. (Reference Lindecrona, Jensen and Jensen3) and Kirkwood et al. (Reference Kirkwood, Huang and McFall2) failed, which again could be due to the difference in the experimental designs such as differences in rice processing or virulence of the strains of B. hyodysenteriae (Reference Pluske, Hampson, Aland and Madec22).

Fermentation of inulin by the indigenous microbiota results in the production of VFA and gases(Reference Roberfroid, Van Loo and Gibson9), so consequently the luminal pH values in the caecum and upper colon decreased with increasing levels of dietary inulin. Similarly, the concentration of VFA in the caecum, upper colon and lower colon increased when pigs were fed higher concentrations of inulin. Generally, dietary inclusion of inulin has shown contradictory results with respect to luminal pH values and VFA concentrations. Hansen et al. (Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7) observed that feeding 80 g/kg inulin to pigs experimentally challenged with B. hyodysenteriae had no influence on large-intestinal pH values and total VFA concentrations, whereas Halas et al. (Reference Halas, Hansen and Hampson23) using weaner pigs and Loh et al. (Reference Loh, Eberhard and Brunner24) using grower pigs observed lower total VFA concentrations in the large intestine when diets were supplemented with inulin. Nonetheless, the negative correlations between digesta VFA concentration and luminal pH observed in the present study support the notion that undigested carbohydrate entering the large intestine functions as a substrate for fermentative processes which generates a higher concentration of VFA to cause a decrease in pH.

In the present study, feeding increasing levels of inulin significantly influenced the proportion of VFA in the luminal contents, which concurs with previous findings(Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7, Reference Halas, Hansen and Hampson23, Reference Loh, Eberhard and Brunner24). According to Cummings & Macfarlane(Reference Cummings and Macfarlane25), dietary inulin mainly stimulates lactobacilli that produce lactic and acetic acids. However, no increase in acetic acid concentration was observed in the present study, and hence butyrate and valerate concentration should not be affected. However, Bindelle et al. (Reference Bindelle, Leterme and Buldgen26) reported that in human subjects, butyrate-producing bacteria can be net utilisers of acetate to the extent that the proportion of acetate can be the reciprocal of the concentration of butyrate due to bacterial cross-feeding. Indeed, Mølbak et al. (Reference Mølbak, Thomsen and Jensen27) suggested that feeding inulin can cause an increase in lactate-producing bacteria, which in turn can stimulate lactate-utilising butyrate producers such as Megasphaera elsdenii.

VFA produced by the intestinal microbiota are commonly divided into straight-chain fatty acids and BCFA. Straight-chain fatty acids such as acetic, propionic and butyric acids are produced from carbohydrate fermentation, while BCFA such as isobutyric and isovaleric acids are produced by fermentation of proteins(Reference Bauer, Williams and Voigt28, Reference Macfarlane, Gibson and Beatty29). In addition, fermentation of protein in the large intestine normally becomes more evident as carbohydrate availability becomes a limiting factor for microbial fermentation(Reference Jensen, Piva, Bach Knudsen and Lindberg30). Collectively, this could explain the decline in BCFA in the caecum and colon with increasing levels of dietary inulin, as the preferential metabolism of inulin by carbohydrate-fermenting bacteria may have lessened the activity of the proteolytic bacteria. In agreement, Jensen et al. (Reference Jensen, Cox and Jensen18) showed that the production of protein metabolites from microbial fermentation may be reduced by inclusion of NSP.

In addition to BCFA, protein fermentation may be accompanied by an increased production of NH3, indole, phenols, amines and S-containing compounds(Reference Heo, Kim and Hansen31). In the present study, N-NH3 was measured as a marker of protein fermentation in the large intestine, which nonetheless was unaltered by dietary inulin levels. This lack of increased luminal N-NH3 concentrations in the large intestine could be a result of N assimilation by bacteria and/or growth of the caecal and colonic biomass possibly coupled with acidification of the large-intestinal contents, resulting in the conversion of ammonia to the less diffusible NH4+ ion(Reference Gibson and Roberfroid32).

Collectively, the data from the present study suggest that dietary supplementation with inulin probably influenced bacterial populations in the gut, resulting in the observed changes in VFA levels and proportions. These changes may have affected the pathogenesis of SD, for example by inhibiting colonisation by the spirochaete. Different dietary effects on the expression of SD are most probably linked to diet-related changes in the intestinal microbiota(Reference Leser, Lindecrona and Jensen33). Such changes could either inhibit the colonisation of B. hyodysenteriae directly or inhibit any of the synergistic bacteria that have been reported to facilitate colonisation with B. hyodysenteriae (Reference Whipp, Robinson and Harris34).

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that pigs fed 80 g/kg inulin, but not lower concentrations, have a reduced risk of developing clinical SD after experimental challenge with B. hyodysenteriae. These results confirm previous findings by our group(Reference Hansen, Phillips and La7). In addition, the present study underlines that these relative high and expensive dietary inclusion levels are necessary to induce changes in large-intestinal fermentation characteristics. Diets supplemented with 80 g/kg inulin may protect pigs against developing SD by modifying the microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Australian Cooperative Research Centre for an Internationally Competitive Pork Industry, Roseworthy, South Australia. The authors acknowledge Dr Jan Dahl for his advice concerning the statistical analysis. Each author fully contributed to the design, experiment and interpretation of the results in the manuscript. The authors have no conflict of interest to report.