The demand for organic products is increasing rapidly in industrialised countries. In Europe, organic farmland has almost doubled since 2004, reaching 5·7 % of the total agricultural area in the EU-28 in 2013( Reference Willer and Lernoud 1 ). In France in particular, the market has doubled in the past 5 years, and >33 % of the French population consume organic products every week( 2 ).

The non-use of synthetic fertilisers and chemical pesticides assumes that organic production may enhance the nutritional quality of food and in turn health status( Reference Johansson, Hussain and Kuktaite 3 ). Consequently, with environmental and ethical motives, health remains one of the predominant reasons for purchasing organic food (OF)( 2 , Reference Oates, Cohen and Braun 4 – Reference Wier, O’Doherty Jensen and Andersen 7 ). The content of phenolic compounds, vitamin C and Mg seems to be higher in most organic crops, as well as n-3 fatty acids in dairy products( Reference Wunderlich, Feldman and Kane 8 – Reference Barański, Średnicka-Tober and Volakakis 11 ); however, the superiority of the overall nutritional quality of organically grown crops has not been definitively established( Reference Dangour, Dodhia and Hayter 12 ). Some animal and in vitro studies( Reference Johansson, Hussain and Kuktaite 3 , Reference Finamore, Britti and Roselli 13 , Reference Chhabra, Kolli and Bauer 14 ) have been conducted, but very few intervention studies or observational studies addressing the potential benefits of OF in human health have been performed( Reference Huber, Rembiałkowska and Średnicka 15 – Reference Kummeling, Thijs and Huber 19 ). Observational study design is complex and inference of causality is tricky because of residual confounding. Hence, the importance of identifying and understanding the overall profiles of OF consumers is necessary before investigating the potential association with health.

However, detailed descriptions of OF profiles are scant or limited to population subgroups( 2 , Reference Hassan, Monier-Dilhan and Nichele 20 – Reference Eisinger-Watzl, Wittig and Heuer 24 ). In particular, studies reporting diet-related behavioural patterns and health characteristics of OF consumers are scarce. Nevertheless, some characteristics of the organic consumers have emerged from previous studies. For example, frequent OF consumers have been depicted as more educated( Reference Dimitri and Dettmann 21 ), with healthier dietary habits and lower BMI( Reference Oates, Cohen and Braun 4 , Reference Eisinger-Watzl, Wittig and Heuer 24 , Reference Kesse-Guyot, Péneau and Méjean 25 ). Among pregnant women in the Danish Cohort Study, frequent OF consumption was also associated with a healthier lifestyle, older age, higher socio-professional category, vegetarianism, as well as being non-smokers and living in urbanised cities( Reference Petersen, Rasmussen and Strøm 23 ).

In the NutriNet-Santé study, regular organic food consumers (ROFC) have exhibited higher level of education, were more physically active than other groups and had a higher diet quality( Reference Kesse-Guyot, Péneau and Méjean 25 ). However, dietary traits and the health status of this population have not yet been comprehensively described. In particular, food choices are determined by a multitude of factors, including socio-demographic factors but also nutritional knowledge and perceptions.

The aim of the study was to depict, according to OF consumption, using data from the NutriNet-Santé study: (1) dietary traits, (2) disease history, (3) knowledge of the French nutritional guidelines and to test for a modulating effect of OF consumption in the association between nutritional knowledge and dietary consumption.

Methods

Study population

The NutriNet-Santé study is an ongoing web-based prospective observational cohort that aims to investigate the relationship between nutrition and health, as well as the determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status. It was launched in May 2009 in France with a scheduled follow-up of at least 10 years. The design and the methodology of the NutriNet-Santé study have been described in details elsewhere( Reference Hercberg, Castetbon and Czernichow 26 ). Volunteers were recruited via vast multimedia campaigns and through both traditional and online strategies. Individuals older than 18 years, with internet access and residency in France, were eligible for recruitment.

The present study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. The NutriNet-Santé study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the French Institute for Health and Medical Research (IRB Inserm no. 0000388FWA00005831) and the ‘Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés’ (CNIL no. 908450 and no. 909216). All subjects signed an electronic informed consent.

Data collection

Participants filled in self-administrated questionnaires using a dedicated website at baseline and at different months of follow-up. The baseline questionnaires were pilot-tested and then compared against traditional assessment methods( Reference Touvier, Méjean and Kesse-Guyot 27 ).

Organic food consumption data

After 2 months of inclusion in the cohort, participants were asked via an optional questionnaire to provide information about the following eighteen organic products: fruit, vegetables, soya, dairy products, meat and fish, eggs, grains and legumes, bread and cereals, flour, vegetable oils and condiments, ready-to-eat meals, coffee/tea/herbal tea, wine, biscuits/chocolate/sugar/marmalade, other foods, dietary supplements (DS), textiles and cosmetics. The frequency of consumption or else reasons for non-use was assessed for all eighteen products using eight possibilities of response: (1) most of the time; (2) occasionally; (3) never (too expensive); (4) never (product not available); (5) never (‘I’m not interested in organic products’); (6) never (‘I avoid such products’); (7) never (for no specific reason); and (8) ‘I don’t know’.

Individual characteristics

At baseline, self-administered questionnaires were used to collect data on socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics. This included factors such as age, sex, smoking status, physical activity (as measured by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire( Reference Hagströmer, Oja and Sjöström 28 )), place of residence, education, occupation, income and household size. Questions were also asked concerning current dietary practices: weight-loss diet, vegan diet, vegetarian diet and diet to stay fit (type and reason, history).

At baseline, participants also self-reported medical history including personal history of food allergies, asthma, cancer, CVD (such as myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, angioplasty, myocardial revascularisation, stroke and transient ischaemic attack), hypertension, as well as diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia. If the participant answered yes, he/she completed the information by self-reporting the year of diagnosis and current use of medication.

Dietary data

At baseline, participants were asked to provide three non-consecutive self-administrated web-based 24-h dietary records via a dedicated online platform specifically developed for self-administration. Days were randomly assigned during a 2-week period including 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day. Participants reported all foods and beverages consumed at breakfast, lunch, dinner and any other occasion for 24 h from midnight to midnight. First, participants had to enter the name of every food item consumed through either a food browser or a dedicated search engine. They then had to estimate portion sizes of foods and beverages using photographs derived from a validated picture booklet( Reference Le Moullec, Deheeger and Preziosi 29 ) representing more than 250 generic foods served in seven portion sizes. Another possibility for the participants was to directly fill in the exact quantity of foods and beverages consumed. Subjects had the option of indicating whether their consumption was typical of their usual diet. Daily dietary intakes of alcohol and nutrients were calculated using the NutriNet-Santé food composition table that includes more than 2100 foods( 30 ). A validation study, comparing this method with objective biomarkers, has been conducted showing an acceptable validity of this method( Reference Lassale, Castetbon and Laporte 31 ).

Adequate intakes of five food groups (fruit and vegetables/dairy products/meat, poultry, seafood and eggs/starchy food and seafood), as defined in the ‘French National Nutrition and Health Program’ (Programme National Nutrition Santé – PNNS), were calculated( Reference Hercberg, Chat-Yung and Chauliac 32 ).

After 2 months of inclusion, an optional questionnaire was administered regarding DS use. Participants were asked whether they had been taking any DS in the past 12 months.

Nutritional knowledge

Knowledge of the official nutritional recommendations as defined by the PNNS was assessed via an optional questionnaire 1 month after inclusion (online Supplementary Table S1). It included recommendations regarding five food groups (fruit and vegetables, dairy products, meat, seafood and starchy food).

Statistical analysis

In the present analysis, subjects who were included before December 2011 (N 104 252) and among them those who completed the OF questionnaire were selected (N 70 069). Among them, we selected those who had three dietary records (N 61 867), who were not under-reporting (N 54 322) and who had no missing covariates, leaving 54 283 subjects.

Identification of under-reporting participants was based on the validated published (current gold standard) method proposed by Black( Reference Black 33 ) using Schofield equations( Reference Schofield 34 ) for estimating metabolic rates. Briefly, BMR was estimated by Schofield equations( Reference Schofield 34 ) according to sex, age, weight and height collected at enrolment in the study. BMR was compared with energy intake by taking into account the physical activity level. A physical activity level of 0·88 was used to identify extremely under-reporting subjects, and a physical activity level of 1·55 was used to identify other under-reporting participants( Reference Black 33 ).

To identify profiles of OF consumers, a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) was performed based on the eight answer possibilities to the eighteen questions regarding the use of organic products including textiles and cosmetics, which were taken into account to better identify behaviours as regards organic products. MCA allows one to analyse the pattern of relationships of several categorical dependent variables, and therefore it enables to extract information from correlations between responses. The first three dimensions were retained based on the eigenvalue>1, scree test criteria and interpretability of the score. In a second step, a cluster analysis, based on the three dimensions in the MCA procedure, was used in order to perform hierarchical ascendant classification using Ward’s method. Five different profiles of OF consumers were thus identified: three clusters of non-organic food consumers (NOFC) whose reasons differed, a cluster of occasional organic food consumers (OOFC) and a cluster of ROFC. Among the NOFC, the reasons were as follows: ‘I avoid organic products’, ‘I am not interested in organic products’ and ‘Organic products are too expensive’. For clarity, we gathered those three clusters into one group.

With regard to socio-demographic characteristics of the sample, P values referred to χ 2 or Kruskal–Wallis tests. All analyses were done separately for men and women. OOFC and ROFC were compared with NOFC (reference category) via a sex-stratified logistic regression analysis regarding dietary behaviours, medical history and nutritional knowledge. Crude and adjusted OR and 95 % CI were provided. Adjustments were made for age, education, income and occupation. In addition, we tested the interaction effect of OF consumption in the relationship between nutritional knowledge and compliance with nutritional guidelines.

To explore bias in selection of the sample, we compared excluded participants because of missing data and those included in the analysis. Compared with those excluded (N 49 969), the volunteers included in our analysis were older (43·7 v. 42·1 years old), were more often never smokers (49·8 v. 47·8 %), were more often post-secondary graduate (64·5 v. 59·6 %) and were more often physically active (34·1 v. 33·8 %) (P value<0·0001).

Analyses were performed with the SAS software (Release 9.3; SAS Institute). Tests of statistical significance were two-sided, and the type I error was set at 5 %.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

Descriptive data on characteristics of the study population across OF consumption are given in Table 1. Among women, 14·9 % were ROFC, 51·5 % were OOFC and 33·6 % reported never eating OF. Among men, 11·0 % were ROFC, 47·8 % were OOFC and 41·2 % were NOFC. Among men, ROFC were younger than other groups, whereas in women ROFC were older than the other groups. In both sexes, the percentage of individuals with a high level of education, as well as a high income, was higher in the ROFC than in NOFC. The percentages of executive and intellectual professions and farmers were higher in ROFC compared with NOFC. The association between living area and OF consumption was not clear-cut. Descriptive data of the overall population are given in online Supplementary Table S2.

Table 1 Characteristics of the sample (Numbers and percentages or mean values and standard deviations; n 54 283)

* P value is based on non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test or χ 2 test.

† By consumption unit in the household: official weighting system by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economics Studies.

‡ As the question was optional, for 5709 participants these data were not available.

Diet-related behaviour

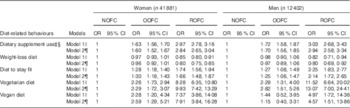

Among both sexes, OOFC and ROFC were more likely to take DS than NOFC. ROFC were more likely to follow a diet to stay fit, or to pursue a vegetarian or a vegan diet, whereas they were less likely to follow a weight-loss diet (Table 2).

Table 2 Association between diet-related behaviours and organic food consumption in the NutriNet-Santé study (Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals; n 54 283)Footnote * Footnote †

NOFC, non-organic food consumers; OOFC, occasional organic food consumers; ROFC, regular organic food consumers.

* Wald’s test of the global effect between clusters (P=0.0001).

† Reference=not having the diet-related behaviour; for example, among women, compared with NOFC, regular consumers were more likely to be dietary supplement users (ORcrude=2·97 and ORadjusted=2·84).

‡ As the questionnaire was optional, for 11 486 participants, these data were not available.

§ Dietary supplement use includes both conventional dietary use and medicinal supplement use.

|| Crude model.

¶ Model adjusted for age, education, occupation and monthly income.

Medical history

In both sexes, ROFC were more likely to report being food allergic (Table 3). The association between asthma and OF consumption was unclear regardless of the sex. In women, OOFC and ROFC were more likely to report a history of cancer. In contrast, in men, no significant results were found for cancer, whereas ROFC were less likely to report CVD. Hypertension, type II diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia were negatively associated with regular food consumption in crude and adjusted models among men and women. Further adjustments were made for smoking status, physical activity and quality of the diet (using modified PNNS Guideline Score (PNNS-GS), a score reflecting the adherence to the recommendations), but findings were not substantially modified (data not shown).

Table 3 Association between medical history and organic food consumption in the NutriNet-Santé study (Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals; n 54 283)Footnote * Footnote †

NOFC, non-organic food consumers; OOFC, occasional organic food consumers; ROFC, regular organic food consumers.

* Wald’s test of the global effect between clusters (P=0·0001).

† Reference=not reporting a disease; for example, among women, compared with NOFC, regular consumers were more likely to be food allergic (ORcrude=2·02 and ORadjusted=1·99).

‡ Crude model.

§ Model adjusted for age, education, occupation and monthly income.

Nutritional knowledge

ROFC were more frequently aware of guidelines for fruit and vegetables and starchy food recommendations, that is plant-based foods, than other consumers (Table 4). In contrast, consumers of OF products were less frequently aware of the recommendations focusing on animal-source foods (dairy products and meat/poultry/seafood/eggs) and tended to underestimate the recommended number of daily portion sizes of such products.

Table 4 Association between knowledge of French nutritional recommendations and organic food consumption in the NutriNet-Santé study (Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals; n 47 410)Footnote * Footnote † Footnote ‡

NOFC, non-organic food consumers; OOFC, occasional organic food consumers; ROFC, regular organic food consumers.

* Wald’s test of the global effect between clusters (P=0·0001).

† As the questionnaire was optional, for 6873 participants data are missing.

‡ Reference=not being aware of the nutritional guideline; for example, among women, compared with NOFC, regular consumers were more likely to know the correct answer about fruit and vegetables recommendations (ORcrude=1·22 and ORadjusted=1·19).

§ Crude model.

|| Model adjusted for age, education, occupation and monthly income.

Nutritional knowledge in relation to adequate intake

Overall, regardless of the level of OF consumption, adherence to recommendations was positively associated with knowledge of the respective nutritional recommendations (OR>1) (Table 5) except for meat/poultry/seafood/eggs recommendation among NOFC and OOFC men and for starchy food recommendation among ROFC men. Recommendations about fruit and vegetables were well known by most of those sampled, as >80 % of each group answered correctly (data not shown). Association between knowledge of the fruit and vegetables guideline and adherence to the related nutritional recommendation was not modulated by OF consumption. However, significant interactions (P<0·10) were found between knowledge of the nutritional guidelines regarding meat, poultry, seafood and eggs and starchy food and OF consumption in the adherence to related nutritional guidelines.

Table 5 Associations between knowledge and adherence to nutritional recommendations stratified by organic food consumption in the NutriNet-Santé study (Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals; n 47 410)Footnote * Footnote †

NOFC, non-organic food consumers; OOFC, occasional organic food consumers; ROFC, regular organic food consumers.

* Wald test of the global effect between clusters (P=0·0001).

† Reference=inadequate intake; for example, in women, among NOFC, individuals who were aware of the recommendation of fruit and vegetables were more likely to have an adequate intake for this food group (ORcrude=1·43 and ORadjusted=1·54).

‡ Model crude.

§ Model adjusted for age, education, occupation and monthly income.

|| P value for an interaction between knowledge of the nutritional guidelines and organic food consumption adequate intake.

In women, when recommendations pertaining to dairy products, meat/poultry/seafood/eggs and seafood were known, the probability of exhibiting adequate intake was higher among ROFC. Among men, similar findings were observed for the recommendations pertaining to meat/poultry/seafood/eggs and seafood.

Discussion

In the NutriNet-Santé study, several socio-demographic and lifestyle factors were specifically associated with OF consumption( Reference Kesse-Guyot, Péneau and Méjean 25 ). The present study extends knowledge of diet- and health-related characteristics of OF consumers in this large cohort and brings a new and original contribution to the understanding of diet-related behaviours and perceptions of OF consumers.

Diet-related behaviours

Among both sexes, it was interesting to observe that ROFC and OOFC were more likely to be DS users and that ROFC were also more likely to follow an intentional diet to stay fit. However, they were less likely to follow a weight-loss diet. These results are consistent with previous works that portray OF consumers to be more health-conscious and more concerned with nutrition and physical activity( Reference Eisinger-Watzl, Wittig and Heuer 24 , Reference Magnusson, Arvola and Hursti 35 , Reference Michaelidou and Hassan 36 ).

OF consumers were also more likely to be vegetarians and vegans than NOFC. This finding supports prior research reporting a strong relationship between vegetarianism and OF consumption( Reference Hughner, McDonagh and Prothero 6 , Reference Torjusen, Brantsæter and Haugen 22 , Reference Petersen, Rasmussen and Strøm 23 , Reference Schifferstein and Oude Ophuis 37 ), which can be mainly attributed to the consideration of ‘animal welfare’ of OF consumers. Indeed, with health, ethical and environmental motives are the main reasons driving OF choice( Reference Bravo, Cordts and Schulze 5 , Reference Pearson, Henryks and Jones 38 ).

Medical history

Given the cross-sectional design of our study, causal inference cannot be made. For instance, it could not be established whether the consumption of OF rather than conventional foods has caused less allergies or whether being allergic has led to a change of dietary behaviour towards an organic-based diet. Nevertheless, a possible interpretation relies on the change of dietary behaviour. People suffering from food allergies may purchase organic rather than conventional food. In accordance with this hypothesis, it has been shown that attitudes towards chemicals are associated with preference for natural food( Reference Dickson-Spillmann, Siegrist and Keller 39 ). This attitude may be a result of perceived risk( Reference Dickson-Spillmann, Siegrist and Keller 39 ) by consumers but also may be related to findings from recent studies( Reference Kummeling, Thijs and Huber 19 ) showing that high level of certain types of pesticides may contribute to the increasing incidence of food allergies in westernised societies( Reference Jerschow, McGinn and de Vos 40 ). Another study has shown that eczema and allergy complaints were 30 % lower in children with an anthroposophic lifestyle that included organic and biodynamic diets( Reference Alfvén, Braun-Fahrländer and Brunekreef 41 ). Furthermore, a consumption of organic dairy products was associated with lower eczema risk( Reference Kummeling, Thijs and Huber 19 ). Consistent with our findings, a previous study showed that families with at least one child suffering from food allergies purchased more organic products( Reference Padel and Foster 42 ). This suggests that the development of food allergies in a household leads to a change of dietary habits that is driven towards an organic, less contaminated and essentially pesticide-free diet( Reference Padel and Foster 42 ).

Similarly, among women, we observed that ROFC were more likely to report a history of cancer. A possible explanation for this observation might be that women diagnosed with cancer change their dietary behaviour towards what they consider to be a healthier diet with less harmful contaminants and pesticide residues. Indeed, it has already been observed that cancer survivors are likely to make dietary changes( Reference Patterson, Neuhouser and Hedderson 43 ).

In a previous work, pesticides in food products have been perceived as a cancerous risk factor( Reference Baghurst, Baghurst and Record 44 ). Furthermore, there is a growing body of evidence that highlights a positive association between certain forms of cancer and exposure to pesticides and contaminants in epidemiological studies( Reference Alavanja, Ross and Bonner 45 – Reference Nasterlack 48 ). In a first and large recent prospective study in women, a decrease in the incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma was associated with consumption of OF but not with other types of cancer( Reference Bradbury, Balkwill and Spencer 49 ).

In contrast, men who regularly consumed OF were less likely to report CVD. Moreover, type II diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia were herein negatively associated with regular OF consumption among both sexes, as well as overweight and obesity, as shown before( Reference Kesse-Guyot, Péneau and Méjean 25 ).

A possible interpretation lies in the representation of perceived risks for cardiometabolic diseases. Unlike cancer or allergies, it may be generally assumed that pesticide residues are not perceived as risk factors for type II diabetes, hypertension or hypercholesterolaemia, whereas cholesterol and fat are more likely to be perceived by the general public as potential risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases.

Nevertheless, even after accounting for confounding factors and adjustment for the quality of diet using the PNNS-GS, ROFC were less likely to have metabolic disorders and CVD than NOFC. From these data, it appears that these types of chronic medical conditions or diseases do not lead to behavioural changes towards an organic diet. Another possible explanation for the observations made might be a direct negative association between cardiometabolic diseases and the level of OF consumption, but this should be tested in the long-term prospective cohort follow-up as planned in the NutriNet-Santé study to remove inverse causality.

Nutritional knowledge

Our study brings a new and original contribution to the understanding of diet-related behaviour and nutritional knowledge of OF consumers. Thus, although OF consumption has been associated with better adherence to nutritional guidelines in the NutriNet-Santé( Reference Kesse-Guyot, Péneau and Méjean 25 ), knowledge of the official nutritional recommendations as defined by the PNNS was not herein systematically associated with ROFC among both sexes. Indeed, ROFC were less likely to know the official recommendations for animal-source foods and conversely were more likely to know those about plant-based food sources. One of the likely explanations for this observation was the highest prevalence of vegetarian and vegan in the organic consumers’ groups. Nevertheless, after adjusting for all previous confounding factors and for vegetable-based diets, that is, vegetarian or vegan diets, no substantial differences were found (data not shown). Another possible explanation could thus be that the specific population of ROFC, who typically exhibit a concern for animal welfare, may be overall more reluctant to report a high requirement for meat/poultry/seafood/eggs and dairy products.

Nutritional knowledge and intake according to organic food consumption

We observed herein a positive association between knowledge of nutritional recommendations and adherence to the corresponding recommendations. This is in accordance with some previous data showing that diet-related knowledge positively affects the quality of dietary intake( Reference Spronk, Kullen and Burdon 50 ). However, it is noteworthy that NOFC and OOFC males exhibited specific behaviours in terms of knowledge and adherence to meat/poultry/seafood/eggs recommendation. Men are known to be large consumers of meat and poultry produce( Reference Shiferaw, Verrill and Booth 51 ). In our study, we may hypothesise that NOFC and OOFC males have such a strong appetence for meat that even being aware of the guidelines seems to be a low determinant of how much they decide to intake. This is not true anymore for ROFC for whom ethical considerations seem to prevail on the intake. Therefore, for these consumers, the knowledge of the related guideline comes along with a compliance with this guideline.

No prior studies have considered the interaction between nutritional knowledge and OF consumption in affecting adequate food intake. In the present study, for several dietary outcomes, significant interactions were found between knowledge of the nutritional guidelines and OF consumption. With regard to fruit and vegetables, OF consumption did not modulate the association between knowledge of the recommendation and adherence to recommended intake regardless of the sex. This can be explained by the high fruit and vegetable intake of RFOC (among women: 65·1 % of ROFC follow the fruit and vegetables guidelines v. 43·7 % of NOFC; among men: 66·5 v. 50·1 %; online Supplementary Table S3). RFOC are such big consumers of fruit and vegetables that being aware of the recommendation does not seem to have a role in the intake.

In contrast, as regards starchy food and meat/poultry/seafood/eggs food groups, significant interactions were found in both sexes. A similar finding was observed for seafood and dairy products among women. For these food groups, female OF consumers seemed to be more likely to adopt the public health nutritional recommendations when they were aware of them.

These results tend to corroborate the findings of some previous works: OF consumers exhibit particular dietary profiles and seem to consider themselves more responsible for their own health. They might be more likely to undertake preventive health action than the general population( Reference Michaelidou and Hassan 36 , Reference Goetzke, Nitzko and Spiller 52 ). This goes along with health concern of OF consumers, as health is one of the main reasons to consume OF.

Overall, the strengths of our study pertain to a substantially large sample size. However, several limitations to this study should be mentioned. The subjects enrolled in our study were volunteers and were certainly more interested in nutritional issues including sustainable food issues and healthy lifestyle than the general population. This may explain some recruitment biases. Caution is therefore needed when generalising the results. Thus, although the participants of the NutriNet-Santé cohort study exhibited marked socio-demographic diversity, some subgroups are under-represented (unemployed, immigrants, elderly people) and the proportions of women and relatively well-educated individuals are notably larger when compared with French census data( Reference Andreeva, Salanave and Castetbon 53 ). Thus, when compared with the French general population, the participants included in our study were older, more often women (77·2 v. 52·4 %) and more often well educated (64·5 % were post-secondary graduate v. 24·9 %)( 54 ). Besides, when compared with the general population, individuals in our sample tended to be more aware of the nutritional recommendations except for starchy foods. Thus, regarding knowledge of the nutritional guidelines in France, the Health Nutrition Barometer has shown( 55 ) that 61·8 % of the individuals were aware of the recommendation for fruit and vegetables (v. 87·1 in our study), 30·8 % for meat seafood and eggs (v. 75·5 % in our study), 75·0 % for seafood (87·0 % in our study) and 58·6 % for starchy foods (27·9 % in our study). In addition, OF consumers exhibiting a particular interest for the topic were probably more inclined to complete the optional questionnaire than NOFC. Thus, the percentage of ROFC was probably not representative of the percentage observed in the French population. Nevertheless, the behaviours and attitudes towards OF have most likely remained unchanged.

Second, data collection is based on self-reported questionnaires, which are prone to measurement error. Finally, the present study was cross-sectional, and it does not enable to conclude about whether OF consumption has a beneficial impact on health.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first study depicting a wide range of factors including dietary behaviours and health-related profiles according to OF consumption in a very large adult cohort. Our results shed new light on OF consumers’ profiles and raise questions about the perception of OF, the factors driving OF consumption, as well as the actual impact of these food products on health. Further investigations, including observational prospective studies and clinical trials, are needed to fill the gap in current knowledge. Specifically, it could be useful to properly control for potential confounders in future studies on the association between OF and health.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the scientists, dietitians, technicians and assistants who helped carry out the NutriNet-Santé study, and all dedicated and conscientious volunteers. The authors especially would like to thank Gwenaël Monot, Mohand Aït-Oufella, Paul Flanzy, Yasmina Chelghoum, Véronique Gourlet, Nathalie Arnault, Fabien Szabo and Laurent Bourhis. The authors also thank Voluntis (a healthcare software company) and MXS (a software company specialised in dietary assessment tools) for developing the NutriNet-Santé web-based interface according to our guidelines.

The present study was supported by the French National Research Agency (Agence Nationale de la Recherche) in the context of the 2013 Programme de Recherche Systèmes Alimentaires Durables (ANR-13-ALID-0001). The NutriNet-Santé cohort study is funded by the following public institutions: Ministère de la Santé, Institut de Veille Sanitaire, Institut National de la Prévention et de l’Education pour la Santé, Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers and Paris 13 University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Conceived and designed the experiments: S. H., P. G., E. K.-G., S. P. and C. M. Performed the experiments: S. H., P. G., E. K.-G., S. P. and C. M. Analysed the data: J. B. and E. K.-G. Wrote the paper: J. B. and E. K.-G. Involved in interpreting results and editing the manuscript: J. B., C. M., S. P., P. G., S. H., D. L. and E. K.-G. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1017/S0007114515003761