In humans, DNA is methylated by the addition of a methyl group to the 5′ position on cytosine (C) residues where the C is followed by a guanine (G) residue – that is, a CpG dinucleotide. This methylation is catalysed by DNA methyl transferase using S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) as the methyl donor. DNA methylation is a component of a suite of epigenetic marks and molecules, which also includes post-translational modification of histones and small non-coding RNA. These epigenetic mechanisms are functionally important because they are key players in the regulation of gene expression( Reference Mathers, Strathdee and Relton 1 ).

Patterns of DNA methylation change during development and ageing, differ between cell types and are altered in multiple diseases including cardiovascular and neoplastic diseases and neurological disorders( Reference Kandi and Vadakedath 2 ). Altered DNA methylation is an early and consistent event in the development of cancer, including colorectal cancer (CRC)( Reference Sakai, Nakajima and Kaneda 3 ), where it plays a causal role through silencing of tumour suppressor genes and activation of oncogenes. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns result in reduced DNA integrity and stability, development of mutations, changes in gene expression and chromosomal modifications( Reference Kim, Golub and Park 4 ). DNA methylation, measured in target or surrogate tissues, has been developed as a diagnostic, prognostic or predictive biomarker for several diseases( Reference Chen, Gaudino and Pass 5 – Reference Levenson 7 ). However, DNA methylation patterns differ between cell and tissue types and may respond differently to interventions( Reference McKay, Xie and Harris 8 ) so that DNA methylation assayed in a surrogate tissue may not be reflective of the target tissue.

Patterns of DNA methylation respond to many environmental exposures and lifestyle factors including diet( Reference Mathers, Strathdee and Relton 1 , Reference Patai, Molnár and Kalmár 9 ). Nutritional factors can affect DNA methylation by modifying the activity of enzymes involved in DNA methylation such as DNA methyltransferase or by changing the availability of methyl donors for SAM synthesis( Reference McKay and Mathers 10 ). Experimental studies using tissue culture and animal models have demonstrated effects of multiple dietary factors including polyphenols, flavonoids and phyto-oestrogens on DNA methylation( Reference Vanden Berghe 11 ), some of which have also been reported in observational studies in humans. However, folic acid supplementation remains the most widely studied nutritional factor affecting DNA methylation( Reference Lim and Song 12 , Reference Lamprecht and Lipkin 13 ). Most of the evidence of effects of dietary factors on DNA methylation in humans comes from cross-sectional observational studies and there appear to be few relevant intervention studies( Reference Lim and Song 12 ).

The aim of this study was to undertake a systematic review of intervention studies in adult humans that involved diet or dietary factors and which reported DNA methylation as an outcome to (i) synthesise the evidence for causal links between specific dietary factors and corresponding changes in DNA methylation and (ii) ascertain the utility of easier-to-collect surrogate samples for investigating effects of dietary factors on DNA methylation in target tissues. To our knowledge, no prior systematic review has addressed these questions.

Methods

The systematic review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist and flow chart( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 14 ) and was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42017072315).

Search strategy and screening

A total of three databases were searched (Embase, Scopus and Medline) from inception until April 2017 by using the following search terms: ((methylation [Mesh] OR dna methylation [Mesh] OR methylat*) AND ((Supplement OR supplement* OR dietary supplements [Mesh]) OR (trial* OR clinical trial [Mesh]) OR (Intervention OR intervention*))).

Articles were screened against the following pre-specified inclusion criteria – (1) study design: any intervention study, randomised or non-randomised; (2) participants: adult human beings (≥16 years old); (3) intervention: dietary interventions (single, multiple or combined with other modalities – e.g. physical activity) and (4) outcome: DNA methylation measured using any methodology as an outcome (primary or secondary) assessed before and after the intervention. Where DNA methylation was assessed after the intervention only, randomised controlled trials (RCT) only were included in the review. Where DNA methylation was assessed before intervention only, studies were excluded.

Studies that recruited patients undergoing active treatment of cancer including chemotherapy or/and radiotherapy were excluded because of the likelihood that such therapies would confound the dietary effects. In studies involving pregnant women, the study was included if the outcome was assessed in tissue samples from the pregnant woman, but not if the measurements were made in the offspring or products of conception – for example, cord blood or placenta.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two independent investigators (K. E. and F. C. M.). This was followed by accessing full texts to ensure meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancy regarding the decision to include a study was resolved by a third reviewer (J. C. M.).

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following data were collected using a pre-tested standard form: year of publication, study design, health or disease status of participants, number of participants, nature of dietary intervention, intervention duration, sample site, DNA methylation assessment method (including genomic loci, where appropriate), DNA methylation levels of participants before and after intervention with measures of variance and level of significance. These data were uploaded into Microsoft® Excel 2013 and used to compile a narrative synthesis of the results that is reported below using descriptive statistics (e.g. percentages) and summary tables.

Meta-analysis and meta-regression

Eligible studies were included in a meta-analysis conducted using the Review Manager software (version 5.3, the Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) and intervention effects were quantified using a random-effects model (owing to heterogeneity) and standardised mean difference (owing to different methods used to quantify DNA methylation). In addition, risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using χ 2 statistic (expressed as P value) and I 2 statistics (expressed as percentage) using Review Manager version 5.3.

Results of meta-analysis of different techniques for quantification of global DNA methylation (direct v. indirect measurement and different direction of effects) were examined using comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA) software (version 2; Biostat) using a random-effects model (owing to heterogeneity) and standardised mean difference. The CMA software was also used to carry out meta-regression analysis using a mixed-effect model, and publication bias was examined via funnel plots and Egger’s regression test (expressed as P value).

Results

The PRISMA flow chart (online Supplementary Fig. S1) summarises the outcomes of the search strategy. Out of 22 149 titles, sixty intervention studies were included, of which thirty-nine studies (65%) were RCT and seven (12%) were cross-over RCT. The number of participants recruited per study ranged from 7 to 388, with a median value of 34.

Across sixty trials, twenty-two different dietary interventions were applied. The most common intervention agent was folic acid, which was tested in one-third of the studies (n 20, 33%) followed by a low-energy diet (n 5, 8%) and multi-vitamin supplements (n 5, 8%) (online Supplementary Fig. S2). One-third of the studies (twenty trials) recruited healthy individuals, whereas participants with sixteen disease conditions or risk factors were studied in the remaining forty papers. Studies on patients with colorectal disease (n 13) represented 22% of the total, whereas seven studies (11%) recruited obese and/or overweight patients (online Supplementary Fig. S3).

A wide range of DNA methylation assessment methods (thirty in total; see online Supplementary Table S2) were used, and only ten studies (17%) reported outcomes from a combination of types of DNA methylation assessment (online Supplementary Table S1). Global DNA methylation was investigated in more than half of the trials (n 31, 52%) and was the sole DNA methylation measurement in twenty-six studies (43%). The most common techniques were the [3H]-methyl acceptance assay (n 9, 15%) for estimation of global DNA methylation and Sequenom’s MassARRAY EpiTyper (n 7, 12%) for methylation at specific genomic loci. Bisulphite sequencing, using ten different techniques, was applied in more than one-third of the trials (n 21, 35%) (online Supplementary Table S3).

Methylation in DNA extracted from six different tissues was studied (online Supplementary Fig. S4). Blood samples were used in more than half of the trials (n 32, 53%), with leucocytes being the most common cell fraction studied (n 12, 20%). Methylation in DNA from colorectal mucosal biopsies was reported in sixteen studies (27%). Other tissues included adipose tissue, muscle, semen and mammary tissue. In the text below, the results of the intervention studies have been categorised according to the tissue/sample site and dietary intervention.

Effects of dietary intervention on DNA methylation in blood

Of the thirty-two trials that reported data from blood samples, seventeen were RCT with one cross-over RCT. In all, eight studies used folic acid as the intervention agent (Table 1)( Reference Jacob, Gretz and Taylor 15 – Reference Martín-Núñez, Cabrera-Mulero and Rubio-Martín 22 ), whereas seven trials involved weight-loss interventions (Table 2)( Reference Milagro, Campión and Cordero 23 – Reference Duggan, Xiao and Terry 29 ). Other studies are summarised in Table 3 ( Reference Kok, Dhonukshe-Rutten and Lute 30 – Reference Pusceddu, Herrmann and Kirsch 46 ).

Table 1 Effects of folic acid supplementation on DNA methylation in different blood samples

RCT, randomised controlled trial; ↓, decrease; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; ↑, increase; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase.

Table 2 Effects of weight-loss nutritional interventions on DNA methylation in different blood products*

RCT, randomised controlled trial; NA, not available; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; ↑, increase; CpG, cytosine-phosphate-guanosine; ↓, decrease; RESMENA, MEtabolic Syndrome REduction in Navarra; LUMA, luminometric methylation assay.

* For full names of each of the genes listed in this table by their ID, please see Supplementary Table S4.

Table 3 Effects of different dietary interventions (other than folic acid and weight-loss interventions) on DNA methylation in different blood products*

RCT, randomised controlled trial; ↑, increase; TDS, ter die sumendum (three times per d); ↓, decrease; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; HTN, hypertension; F/V, fruits/vegetables; MedDiet, Mediterranean diet; EVOO, extra-virgin olive oil; PBC, peripheral blood cells; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; LCPUFA, long-chain PUFA; DM, diabetes mellitus; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; NA, not available.

* For full names of each of the genes listed in this table by their ID, please see Supplementary Table S4.

Folic acid supplementation

Jacob et al. ( Reference Jacob, Gretz and Taylor 15 ) and Rampersaud et al. ( Reference Rampersaud, Kauwell and Hutson 16 ) quantified global DNA methylation in postmenopausal females, and reported decreased methylation in response to folate depletion. Following folic acid supplementation, that change was revered in the study by Jacob et al. ( Reference Jacob, Gretz and Taylor 15 ), but not in the study by Rampersaud et al. ( Reference Rampersaud, Kauwell and Hutson 16 ), who found no significant change after repletion in a study with greater power.

In male patients with hyperhomocysteinaemia, Ingrosso et al. ( Reference Ingrosso, Cimmino and Perna 17 ) conducted a non-randomised folic acid supplementation study and observed significantly increased global DNA methylation, whereas Pizzolo et al. ( Reference Pizzolo, Blom and Choi 18 ) reported no significant change after folic acid supplements in a non-RCT. Similarly, in an RCT involving 216 patients with hyperhomocysteinaemia, Jung et al. ( Reference Jung, Smulders and Verhoef 22 ) found no effect of folic acid supplementation over 3 years on global DNA methylation in leucocytes. This lack of effect of folic acid supplementation on global DNA methylation was also observed in RCT involving healthy volunteers( Reference Basten, Duthie and Pirie 20 ) and women of reproductive age( Reference Crider, Yang and Berry 21 ).

The combination of folic acid with other nutrients involved in one-carbon metabolism including methionine( Reference van der Kooi, de Greef and Wohlgemuth 31 ), choline and betaine( Reference Abratte, Wang and Li 39 ) and vitamin B12 ( Reference Stopper, Treutlein and Bahner 44 ) did not modify methylation at specific genomic loci (Table 3). An exception was Kok et al. ( Reference Kok, Dhonukshe-Rutten and Lute 30 ) who investigated effects of folic acid (0·4 mg/d) and vitamin B12 (0·5 mg/d) and demonstrated significant changes in DNA methylation at many CpG sites in or close to DIRAS3, ARMC8 and NODAL genes. (For full names of each of the genes listed in this paper by their ID, please see Supplementary Table S4.)

Weight-loss nutritional intervention

Nicoletti et al. ( Reference Nicoletti, Cortes-Oliveira and Pinhel 25 ) compared the effects of reduced dietary energy intake and bariatric surgery on DNA methylation in buffy coat samples from obese patients in a non-randomised study. Compared with baseline, methylation of IL-6 increased in those exposed to dietary energy restriction and decreased in the bariatric surgery group. However, there was no effect of either intervention on global DNA methylation (assessed as methylation of the repeated element LINE1). Duggan et al. ( Reference Duggan, Xiao and Terry 29 ) did not detect any significant changes in LINE1 methylation in leucocytes from 298 postmenopausal obese females after 1 year of exposure to an energy-restricted diet, exercise or both. Delgado-Cruzata et al. ( Reference Delgado-Cruzata, Zhang and McDonald 28 ) reported that LINE1 methylation increased after 6 months of a weight-loss programme involving both diet and exercise in twenty-four breast cancer survivors, whereas, in contrast, Martín-Núñez et al.( Reference Martín-Núñez, Cabrera-Mulero and Rubio-Martín 26 ) found significantly lower LINE1 methylation in 310 participants after 9 months of intervention with a combination of Mediterranean diet, physical activity and education aiming at weight loss.

Effects of dietary intervention on DNA methylation in the colorectal mucosa

Methylation of DNA extracted from colorectal mucosal biopsies was investigated in sixteen studies, most of which (n 14) were RCT. The large majority (n 11) involved patients with colorectal adenomas, whereas only three studies recruited healthy participants. Other disease conditions included familial adenomatous polyposis and ulcerative colitis (one trial each). Folic acid was the intervention agent in ten trials (Table 4), whereas other intervention studies investigated effects of black raspberries, vegetables, non-digestible carbohydrates, Bifidobacterium lactis, high-amylose maize starch and combined folic acid and vitamin B12 (Table 5).

Table 4 Effects of folic acid supplementation on DNA methylation in colorectal mucosa*

RCT, randomised controlled trial; FA, folic acid; ↑, increase; UC, ulcerative colitis; ERa, oestrogen receptor α.

* For full names of each of the genes listed in this table by their ID, please see Supplementary Table S4.

Table 5 Effects of different dietary supplementation (other than folic acid) on DNA methylation in colorectal mucosa*

RCT, randomised controlled trial; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; ↑, increase; NA, not available; UVI, UV imager; CRC, colorectal cancer; ↓, decrease; FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis; MDBC-seq, methyl-CpG binding domain-based capture and sequencing; RS, resistant starch.

* For full names of each of the genes listed in this table by their ID, please see Supplementary Table S4.

Effects of folic acid on DNA methylation status in colorectal biopsies differed between studies. In all, eight trials studied effects on global methylation. Figueiredo et al. ( Reference Figueiredo, Grau and Wallace 52 ) randomised 388 patients with adenoma to a folic acid supplement or a placebo and reported no effect on global DNA methylation. That finding was supported by results from another RCT( Reference Cravo, Glória and Salazar de Sousa 48 ) and from a non-RCT( Reference Protiva, Mason and Liu 53 ). However, five RCT found increased global DNA methylation in adenoma patients following folic acid supplementation. Wallace et al. ( Reference Wallace, Grau and Levine 54 ) and Al-Ghnaniem Abbadi et al. ( Reference Al-Ghnaniem Abbadi, Emery and Pufulete 55 ) found no effect of folic acid on DNA methylation of SFRP1, ESR1 or MLH1 in patients with adenoma. Findings from meta-analysis and meta-regression of the available evidence for the effects of folic acid supplementation on global DNA methylation are presented later in this article.

Wang et al. ( Reference Wang, Arnold and Huang 60 ) found a significant lower methylation of SFRP2 and SFRP5 after consumption of black raspberries by patients at high risk of CRC, but there were no effects of this food on LINE1, WIF1 or SPRP2 methylation( Reference Wang, Burke and Hasson 61 ). van den Donk et al. ( Reference van den Donk, Pellis and Crott 57 ) reported significantly higher global DNA methylation and increased methylation of specific genes (O6-MGMT, hMLH1, p14ARF, p16INK4A and RASSF1A) but decreased APC methylation after use of folic acid and vitamin B12 supplements. Increased consumption of vegetables( Reference van Breda, van Delft and Engels 58 ), non-digestible carbohydrates( Reference Malcomson, Willis and McCallum 62 ) or maize starch/B. lactis ( Reference Worthley, Le Leu and Whitehall 59 ) did not affect methylation of the specific genes studied in each of those trials (Table 5).

Effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation in adipose tissue

Adipose tissue samples were obtained from subcutaneous tissues of the abdomen in four out of five intervention studies that investigated the effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation (Table 6) (Cordero et al. ( Reference Cordero, Campion and Milagro 64 ) did not report the site of biopsy). In all, two non-RCT investigated the effect of energy restriction in obese women. Bouchard et al. ( Reference Bouchard, Rabasa-Lhoret and Faraj 63 ) reported that energy restriction for 6 months altered methylation at three specific loci (1p36, 4q21 and 5q13), whereas 8 weeks of restricted energy intake had no effect on methylation of LEP and TNFα in females of reproductive age( Reference Cordero, Campion and Milagro 64 ).

Table 6 Effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation in adipose cells*

RCT, randomised controlled trial; CpG, cytosine-phosphate-guanosine; LBW, low birth weight; NBW, normal birth weight; ↑, increase; LEP, leptin; ADIPOQ, adiponectin, C1Q and collagen domain containing; CHO, carbohydrates.

* For full names of each of the genes listed in this table by their ID, please see Supplementary Table S4.

Hjort et al. ( Reference Hjort, Jørgensen and Gillberg 66 ) found that 36 h fasting after 2 d of a standard diet increased methylation of LEP and ADIPOQ significantly in normal-birth-weight (NBW) adults but not in those with low birth weight (LBW). In contrast, Gillberg et al. ( Reference Gillberg, Jacobsen and Rönn 65 ) reported that overfeeding with fat increased methylation of PPARGC1A in adults with LBW but not those of NBW. Overfeeding with a diet rich in saturated and unsaturated fatty acids increased mean genome-wide methylation (assayed using a BeadChip Array; Illumina) in healthy adults( Reference Perfilyev, Dahlman and Gillberg 68 ).

Effects of dietary interventions DNA methylation in other tissues

Table 7 summarises findings from studies that reported effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation in muscle biopsies, mammary cells and semen. In all, three cross-over RCT studied effects of high-fat overfeeding on DNA methylation on muscle cells of vastus lateralis in healthy adults, and one study( Reference Brøns, Jacobsen and Nilsson 69 ) reported that this intervention increased PPARGC1A methylation in NBW adults.

Table 7 Effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation in specialised tissues (mammary tissue, muscle cells and semen)*

RCT, randomised controlled trial; NBW, normal birth weight; LBW, low-birth-weight; ↑, increase; ER, oestrogen receptor; NA, not available; ↓, decrease; RRBS, reduced representation bisulfite sequencing; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; RLGS, restriction landmark genomic scanning; MCIp, methyl-CpG immunoprecipitation.

* For full names of each of the genes listed in this table by their ID, please see Supplementary Table S4.

DNA methylation in mammary cells was investigated in two RCT( Reference Zhu, Qin and Zhang 67 , Reference Qin, Zhu and Shi 72 ), with no significant change observed after interventions with soya isoflavones or with trans-resveratrol. However, Zhu et al. ( Reference Zhu, Qin and Zhang 67 ) found a significant inverse correlation between methylation of RASSF1A and serum trans-resveratrol concentration in healthy women at increased risk of breast cancer.

Methylation of DNA in semen after folic acid supplementations was assessed in two intervention studies( Reference Aarabi, San Gabriel and Chan 73 , Reference Chan, McGraw and Klein 74 ). Folic acid supplements resulted in reduced global DNA methylation in men with idiopathic infertility( Reference Aarabi, San Gabriel and Chan 73 ) but had no effect on global DNA methylation in healthy fertile men( Reference Chan, McGraw and Klein 74 ).

Meta-analysis and meta-regression of effects of folic acid supplementation on global DNA methylation

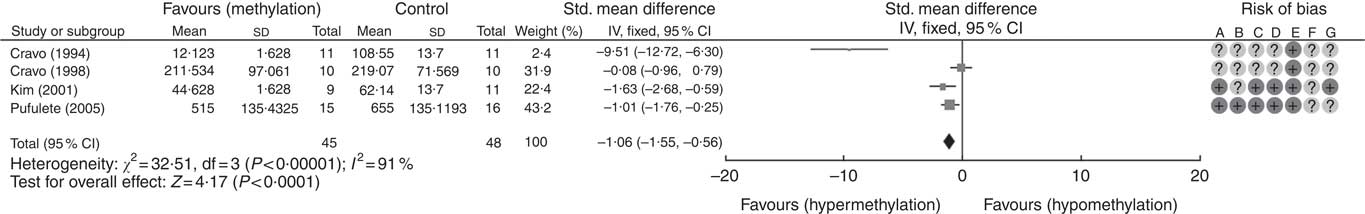

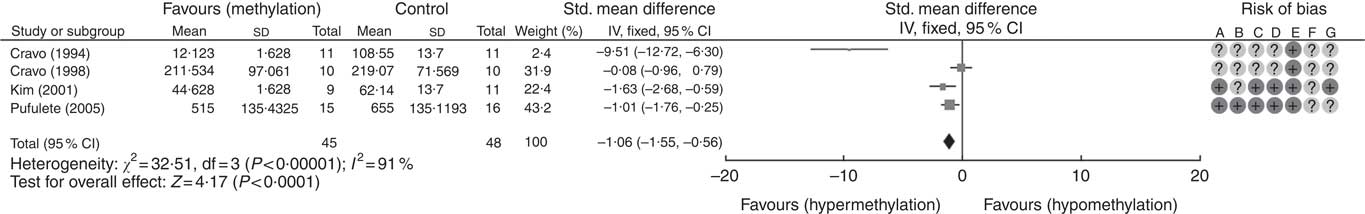

A total of five RCT used the [3H]-methyl acceptance assay for quantification of global DNA methylation in colorectal mucosal samples. In all, one study( Reference Cravo, Glória and Salazar de Sousa 48 ) was excluded as the study reported the significance of results only following folic acid supplementation but did not provide numerical data on DNA methylation. For the remaining four studies, meta-analysis showed that folic acid supplementation increased global DNA methylation significantly (P<0·0001) but there was significant heterogeneity between the included trials (I 2: 91%, P<0·001). Overall, there was low or unclear risk of bias owing to failure of reporting of randomisation and blinding (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Forest plot and risk of bias assessment of randomised controlled trial studying the effects of folic acid supplements on global DNA methylation in colorectal mucosal samples using [3H]-methyl acceptance assay using Review Manager (version 5.3).

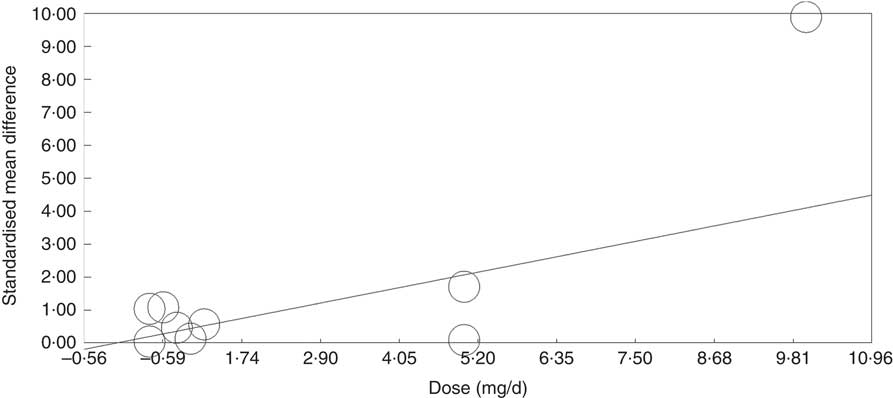

Meta-regression was used to investigate the effects of dose and duration of folic acid supplementation. This revealed that the dose of folic acid had a highly significant (P=0·0046) and positive effect on global DNA methylation (online Supplementary Fig. S5), whereas there was no detectable effect of the duration of intervention (P=0·41).

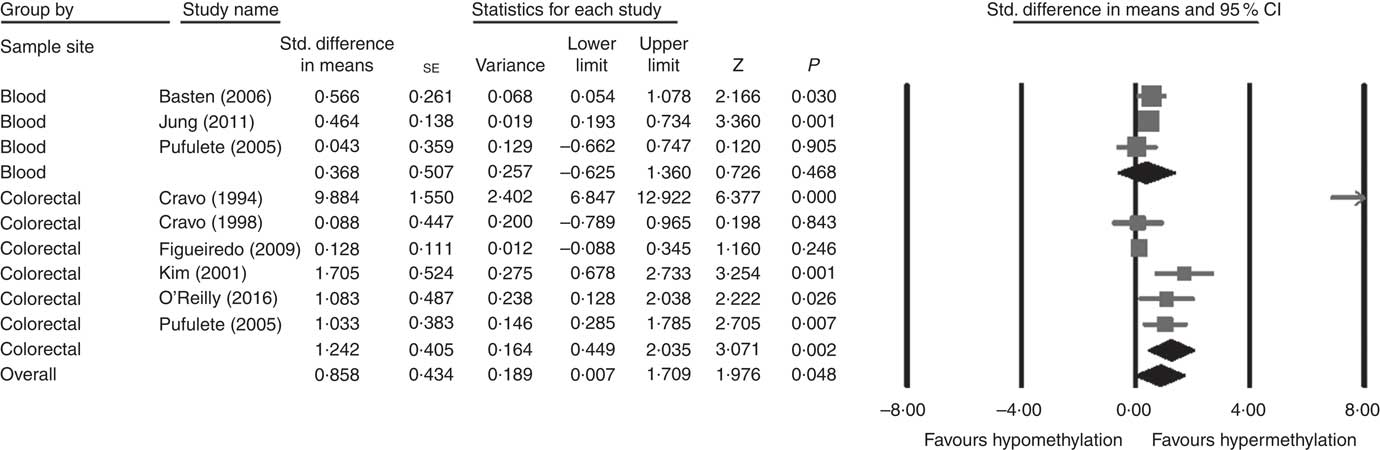

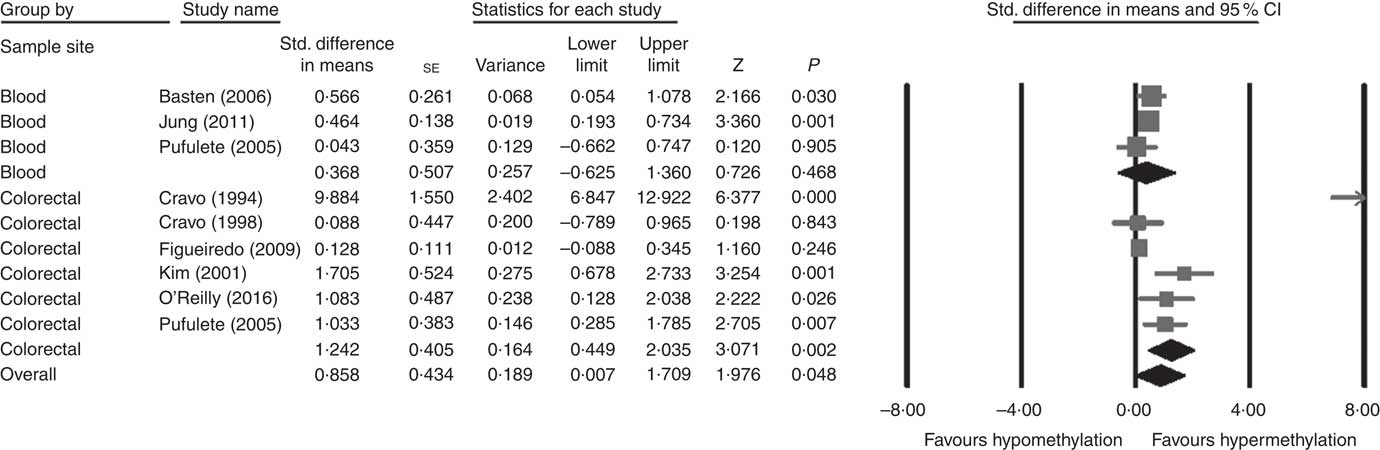

Considering different techniques of quantification of DNA methylation, eight RCT were included for meta-analysis with two subgroups: colorectal (n 6) and blood samples (n 3, as Pufulete et al. ( Reference Pufulete, Al-Ghnaniem and Khushal 51 ) reported data for both colorectal and blood samples). Folic acid increased DNA methylation overall (P=0·048) and in colorectal mucosal samples specifically (P=0·002) (Fig. 2). However, there was no significant effect of folic acid on DNA methylation in blood samples (P=0·468). There was significant heterogeneity in the data for the colorectal subgroup (I 2=91%, P≤0·001), blood subgroup (I 2=84%, P=0·002) and overall (I 2=89%, P<0·001). The test for subgroup differences was also significant (P=0·04, I 2=75·6%) (online Supplementary Fig. S6). No high risk of bias was identified, but information to assess risk of bias was limited owing to incomplete reporting of randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding (online Supplementary Fig. S6).

Fig. 2 Forest plot of randomised controlled trial studying effects of folic acid supplements on global DNA methylation in colorectal and blood samples using different techniques of quantification of DNA methylation using CMA software (version 2).

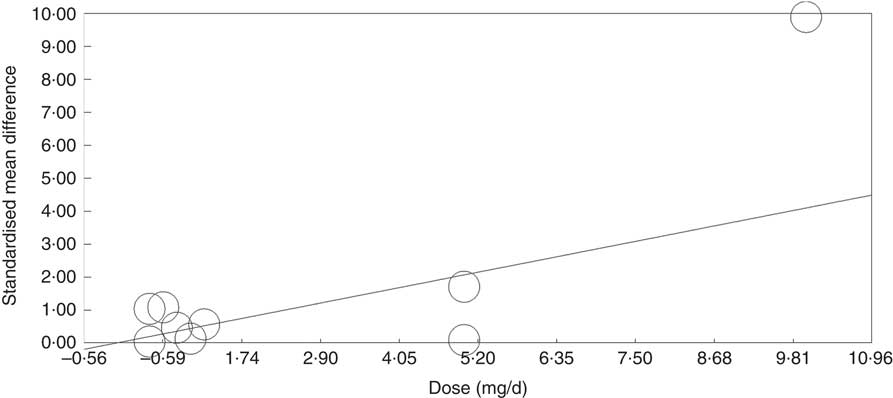

Meta-regression analysis showed that, when investigated across both tissues and all analytical methods, the dose of folic acid used for supplementation had a highly significant and positive effect on global DNA methylation (P=0·0003, Fig. 3). However, it should be noted that this effect is driven by changes in the colorectal mucosa as there was no evidence for an effect on DNA methylation in blood (online Supplementary Fig. S7). Duration of folic acid supplementation (P=0·35) and post-intervention concentration of folate in serum (0·69) had no significant effect.

Fig. 3 Meta-regression of standardised mean difference in relation to the dose of folic acid supplements in the eight randomised controlled trial that were included in meta-analysis involving different techniques of quantification of DNA methylation.

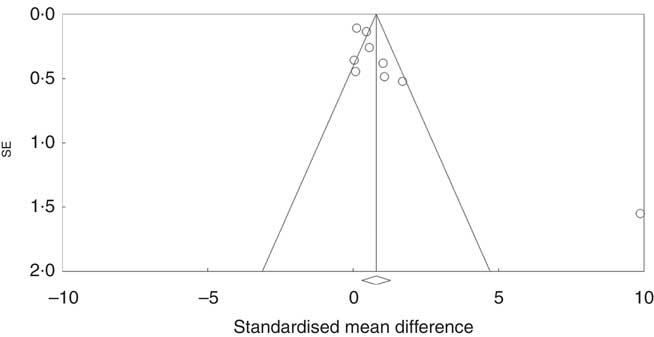

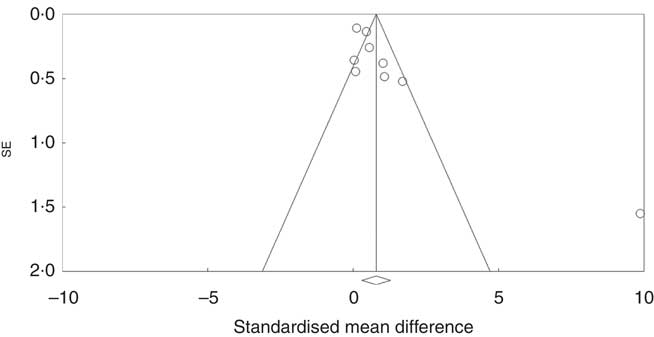

Assessment of publication bias

Investigation of potential publication bias was performed by producing a forest plot (Fig. 4) and statistical analysis using Egger’s test (P=0·03), and this revealed a risk of publication bias for Cravo et al. ( Reference Cravo, Fidalgo and Pereira 47 ). This study recruited patients with a history of either adenoma or carcinoma, whereas other studies recruited participants with a history of adenoma only. As a sensitivity analysis, meta-analysis was performed with inclusion of results of global DNA methylation in colorectal mucosal samples from the adenoma group only( Reference Cravo, Fidalgo and Pereira 47 ). There was no change in risk of publication bias or significance of results (colorectal subgroup: P=0·02, overall effect: P=0·04, and Egger’s test for publication bias: P=0·0025, online Supplementary Fig. S7). Re-analysis of the data after exclusion of Cravo et al. ( Reference Cravo, Fidalgo and Pereira 47 ) (online Supplementary Fig. S8) revealed a positive trend towards global DNA hypermethylation with folic acid supplementation in both the colorectal subgroup (P=0·08) and overall (P=0·22).

Fig. 4 Funnel plot of standard error by standard differences in means of the eight randomised controlled trial included in the meta-analysis.

Stratification according to methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase genotype

A total of eight intervention studies stratified patients according to a polymorphism in the gene coding methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR; 677C→T variant). When stratification according to MTHFR genotype was applied, a significant change in DNA methylation was reported in four studies. Crider et al. ( Reference Crider, Yang and Berry 21 ) reported a significant increase in global DNA methylation of leucocytes in those participants with the TT variant only following folic acid supplementation, whereas depletion of folic acid caused a significant decrease in global DNA methylation in carriers of the CC variant only. On the other hand, Aarabi et al. ( Reference Aarabi, San Gabriel and Chan 73 ) reported that folic acid supplementation decreased DNA methylation in semen in participants with the TT variant. Global DNA methylation in leucocytes decreased following supplementation with choline in carriers of the CC variant( Reference Shin, Yan and Abratte 32 ) and following cocoa supplementation in those with the TT variant( Reference Crescenti, Solà and Valls 35 ).

Discussion

Principal findings

We identified, and analysed data from, sixty dietary intervention studies in adult human participants that reported effects on DNA methylation. Most studies (53%) reported data from blood analyses, whereas 27% studied DNA methylation in colorectal mucosal biopsies. Some studies investigated effects on global DNA methylation, which were assessed using both direct and indirect methods. The methyl acceptance assay was the assay used most frequently for this purpose, but several studies also assessed methylation of the repeat element LINE1, which makes up 17–18% of the human genome and which has been shown to be an acceptable surrogate for global DNA methylation in many cases( Reference Lisanti, Omar and Tomaszewski 75 ). Other studies interrogated specific genomic loci using either targeted – for example, Sequenom’s MassARRAY EpiTyper – or genome-wide – for example, Illumina Bead array – approaches. Folic acid was the most common intervention agent (33%) followed by low-energy diet (8%) and multivitamins (8%). Meta-analysis revealed that folic acid supplementation increased global DNA methylation significantly in colorectal mucosal samples, whereas meta-regression analysis showed that the dose of supplementary folic acid was the only significant factor (P<0·001) causing this positive relationship.

In all, four out of eight intervention studies reported significant changes in DNA methylation following folic acid supplementation when participants were stratified according to MTHFR 677C→T genotype. Carriage of the T variant at position 677 in the of MTHFR gene is associated with lower folate status, higher circulating homocysteine concentration, reduced global DNA methylation and with increased risk of many disorders( Reference Christensen, Arbour and Tran 76 , Reference Den Heijer, Lewington and Clarke 77 ), including greater cancer risk( Reference Lu, Xie and Wang 78 , Reference Wang, Sasco and Fu 79 ). This finding highlights the importance of considering subgroup classification according to MTHFR polymorphism in future research in effects of folic acid supplementation.

In all, two( Reference Jacob, Gretz and Taylor 15 , Reference Rampersaud, Kauwell and Hutson 16 ) out of three non-RCT reported a significant effect of folate depletion in decreasing global DNA methylation in blood products, but this effect was not observed in colorectal samples( Reference Protiva, Mason and Liu 53 ). While Jacob et al. ( Reference Jacob, Gretz and Taylor 15 ) observed that folic acid repletion reversed the DNA hypomethylation, no such effect was apparent in the study by Rampersaud et al. ( Reference Rampersaud, Kauwell and Hutson 16 ). The participants in the latter study were older (>63 years) than those studied by Jacob et al. ( Reference Jacob, Gretz and Taylor 15 ) (49–63 years), and it is possible that age blunted the speed of response to nutritional repletion. In this systematic review, there was no detectable effect of folic acid supplementation on DNA methylation in blood, but there was a significant effect on methylation of DNA from colorectal mucosal samples.

Possible mechanisms responsible for these findings

The mechanism responsible for such tissue differences in response to folic acid supplementation is not known. In human intervention studies, folic acid supplementation raises folate concentrations in both blood and the colorectal mucosa( Reference Powers, Hill and Welfare 80 ) so that it seems unlikely that there would be differential availability of methyl groups for synthesis of SAM for DNA methylation within blood cells and colonocytes. However, studies in mice have shown that folate depletion leads to tissue-specific effects on DNA methylation at selected genomic loci( Reference McKay, Xie and Harris 8 ). In addition, reduced circulating concentration of folate in blood was associated with DNA hypomethylation in human diabetic liver( Reference Nilsson, Matte and Perfilyev 81 ). Such observations are consistent with cell-type-specific differences in cellular distribution of available methyl groups and/or differences in policing of the DNA methylome.

Strengths and limitations

Poor diet and diet-related factors are major contributors to the burden of ill health, especially cancer and cardiometabolic diseases( Reference Murray, Richards and Newton 82 ). This review summarises the available evidence for the impact of dietary factors on DNA methylation in both health and disease. Our systematic review shows that, in humans, little is known about the effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation in tissues other blood and colorectal mucosa; only one-fifth of the included intervention studies in this review investigated other tissues. In addition, none of the included RCT correlated DNA methylation levels between target tissues and other surrogate tissues. The availability of validated assays for DNA methylation biomarkers in reliable and accessible surrogate tissues, such as blood, would avoid the need for invasive sample collection procedures, such as colorectal biopsies, which would facilitate larger population-based studies( Reference Rockett, Burczynski and Fornace 83 ).

This systematic review faced many challenges in data summary and synthesising the evidence. The effects of dietary interventions on DNA methylation are gene and site specific, dependent on cell type and target tissue, and dose and duration of the interventions( Reference Kim, Golub and Park 4 ). There was great heterogeneity in the methods used for assessing DNA methylation and in the genomic loci investigated. Samples were collected from both healthy individuals and from people with specific diseases, which contributed to the heterogeneity in the available data. Statistical heterogeneity was observed in the meta-analysis of eight trials, which had all tested effects of the same nutrient (folic acid). Most of the included RCT failed to report randomisation methods, allocation concealment or blinding that could lead to selective bias owing to poor choice of methods( Reference Kahan, Rehal and Cro 84 ) and could affect outcome assessment( Reference Feys, Bekkering and Singh 85 ). Failure to report such important methodological aspect results in the inability to assess the risk of bias, which could compromise the overall strength of evidence.

Conclusion

Folic acid supplementation increases global DNA methylation in the colorectal mucosa in a dose-dependent manner. This observation may provide the basis for future research in prevention of bowel cancer as DNA hypomethylation is a consistent event in colonic carcinogenesis( Reference Sakai, Nakajima and Kaneda 3 ). However, little is known about the effects of other dietary factors on DNA methylation patterns in any human tissue. In addition, multiple assays and different genomic loci have been used in investigations of effect of dietary interventions on DNA methylation, which makes it difficult to compare or combine data across studies. Standardisation of outcome measurements would facilitate future research.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

K. E. contributed to formulating the research question, designing the study, carrying the study out, analysing the data and writing the manuscript. F. C. M. contributed as the second independent screener of the titles, and reviewed the manuscript. J. G. L. assisted in designing the study and reviewed the manuscript. D. M. B. was involved in critical review of the manuscript and final approval. J. C. M. was involved in formulating the research question, designing the study, writing up and critical review of the manuscript, as well as in final approval.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary materials

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711451800243X