Concurrent to the ageing population, the prevalence of dementia and cognitive decline is increasing rapidly. In 2012, the WHO called dementia a public health priority, and in 2019, the WHO published its guidelines on risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia, with emphasis on lifestyle-related factors(1,2) .

Studying dietary patterns rather than single nutrients has become pivotal in research on dementia prevention(Reference Scarmeas, Anastasiou and Yannakoulia3). Both the Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) have been associated with reduced risks of dementia and cognitive decline(Reference van den Brink, Brouwer-Brolsma and Berendsen4). The Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet, which integrates elements from both patterns, is specifically designed to enhance cognitive health and has shown promising results in the field of dementia prevention(Reference van Soest, Beers and van de Rest5).

The MIND diet, originally developed in the USA, identifies fifteen food groups recognized for their beneficial or adverse effects on cognitive function. It encourages the consumption of ten food groups (fish; poultry; olive oil; green leafy vegetables; other vegetables; berries; legumes; whole grains; nuts and wine), while advising to limit intake from five food groups (fast and fried foods; pastries, and sweets; butter and stick margarine; red and processed meat; cheese)(Reference Morris, Tangney and Wang6). Together, these food groups should provide macro- and micronutrients and bioactive compounds that have been linked to cognitive health(Reference Barnes, Tian and Edens7–Reference Morris and Tangney9).

Whilst studying the impact of the MIND diet on various health outcomes, including cognitive health, it is important to evaluate dietary adherence. However, inconsistencies and unclarities in the MIND diet scoring process have hindered comparisons across studies(Reference Arnoldy, Gauci and Lassemillante10). When comparing studies across different countries and cultures, it should be taken into account that food groups may consist of different food products due to country-specific dietary habits. Hence, indicating that when the MIND diet, and associated scoring system, is introduced to a new population, the applicability of original food products should be evaluated, adapted if needed, and consequently be reported.

Moreover, in previous studies, scoring has relied on serving sizes, but information is lacking on weight and volume equivalents corresponding to these servings. Given that serving sizes can differ significantly among countries, the absence of reporting weights or volumes of serving sizes further complicates accurate cross-study comparisons(Reference Van der Horst, Bucher and Duncanson11). Thus, an alternative approach, to enhance consistency and comparability, involves using metric quantities in grams and millilitres for reporting of servings in the scoring system.

Measuring adherence to any diet can be done with different dietary assessment methods(Reference Brouwer-Brolsma, Lucassen and de Rijk12). Current literature shows that adherence to the MIND diet is predominantly measured with FFQs(Reference van Soest, Beers and van de Rest5). Existing FFQ are not specifically designed to assess MIND diet adherence and often do not capture all food groups of the MIND diet, resulting in reduced maximum MIND diet adherence scores(Reference van Soest, Beers and van de Rest5). Moreover, if the sole interest is to assess adherence to a specific dietary pattern, comprehensive FFQ can be relatively time-consuming and burdensome compared with a short FFQ. Reducing participant burden, in terms of length of the questionnaire, is especially important for assessment of dietary adherence in older adults, who are known to complete FFQ less often(Reference Maynard and Blane13,Reference Volkert and Schrader14) . In the Netherlands, the Eetscore-FFQ, a brief FFQ, was developed to assess adherence to the Dutch food-based dietary guidelines of 2015, as calculated by the Dutch Healthy Diet 2015 index(Reference de Rijk, Slotegraaf and Brouwer-Brolsma15–Reference Kromhout, Spaaij and de Goede17). Since the Dutch food-based dietary guidelines and the MIND diet share similarities in many food groups (e.g. vegetables, whole grain products, legumes and nuts), an adjusted Eetscore-FFQ has the potential to also assess adherence to the MIND diet.

To facilitate a comparative, reproducible and culturally tailored approach for evaluating adherence to the MIND diet, this study first aimed to translate the MIND diet into a Dutch version (MIND-NL) based on Dutch commonly eaten foods. Thereafter, it was aimed to devise an accompanying scoring system based on consumed quantities in weight or volume amounts rather than in standard serving sizes. The third aim was to adapt the existing Eetscore-FFQ to assess adherence to the MIND-NL diet.

Methods

Modifying food groups and food products to fit the MIND-NL diet

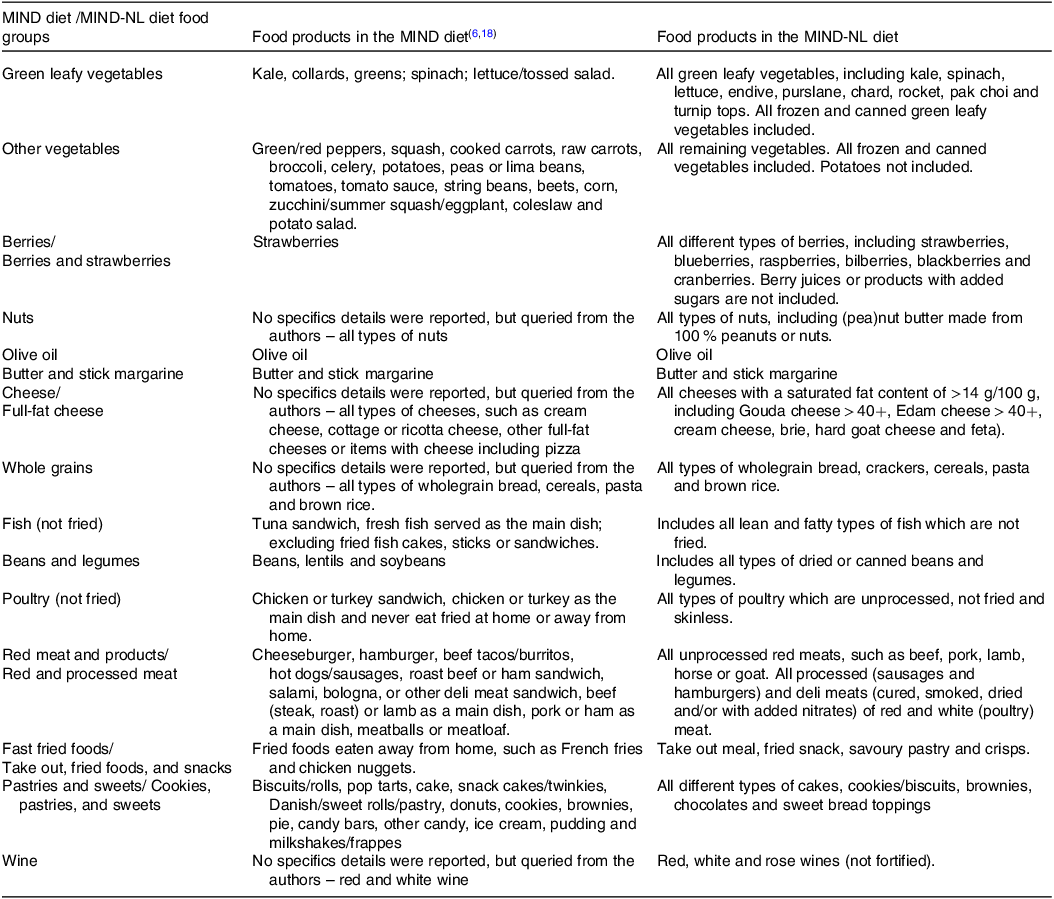

In this article, food groups are defined as the components of the dietary pattern, which are for the MIND diet: fish, poultry, olive oil, green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, berries, legumes, whole grains, nuts, wine, fast and fried foods, pastries and sweets, butter and stick margarine, red and processed meat and cheese. Food products refer to the products that make up each food group (Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of food groups and food products included in the MIND diet and MIND-NL diet

MIND, Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay.

We initially assessed whether the food groups and food products in the original American MIND diet, hereafter referred to as the MIND diet, aligned with those typically found in the Dutch dietary pattern. To accomplish this, we compared the food groups of the Dutch Dietary Guidelines with those of the MIND diet(Reference de Rijk, Slotegraaf and Brouwer-Brolsma15). The Dutch National Food Consumption Survey, a periodic cross-sectional food consumption survey in a nationally representative cohort of the Dutch population, was further used to identify food products commonly consumed in the Netherlands(Reference Van Rossum, Buurma-Rethans and Dinnissen19).

Development of the MIND-NL diet scoring system

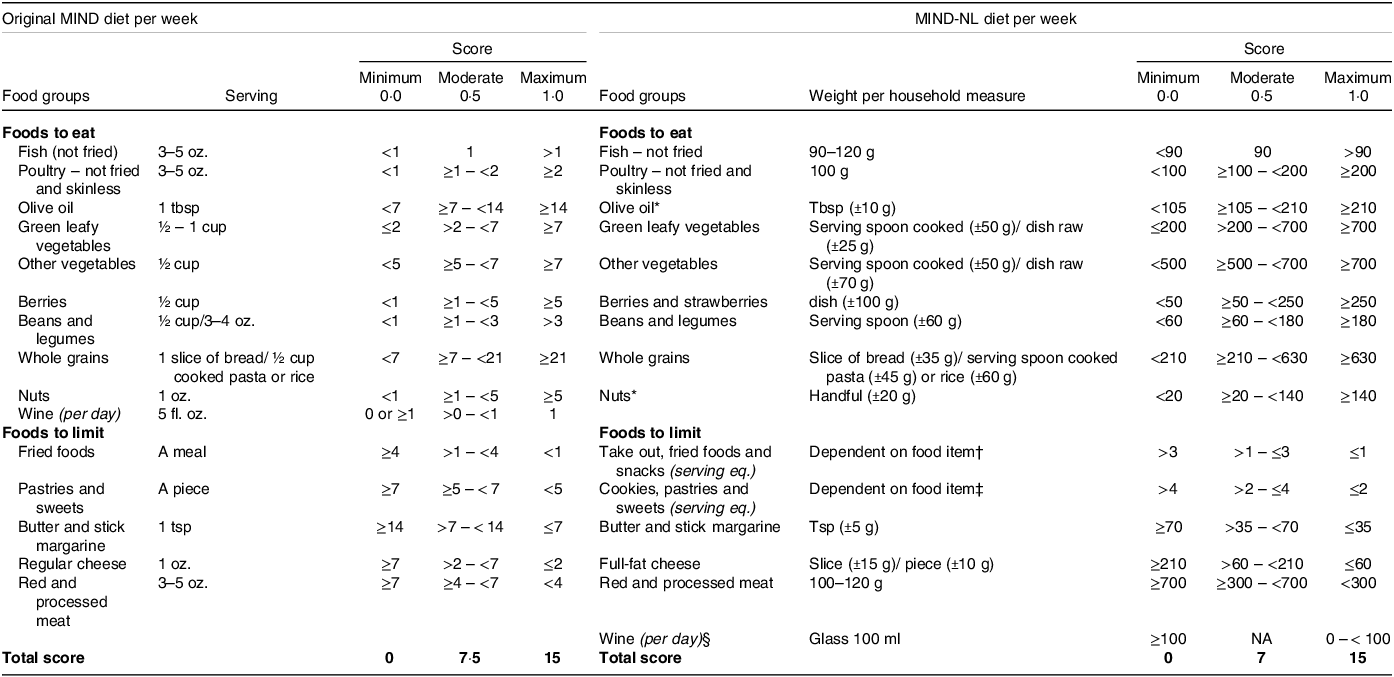

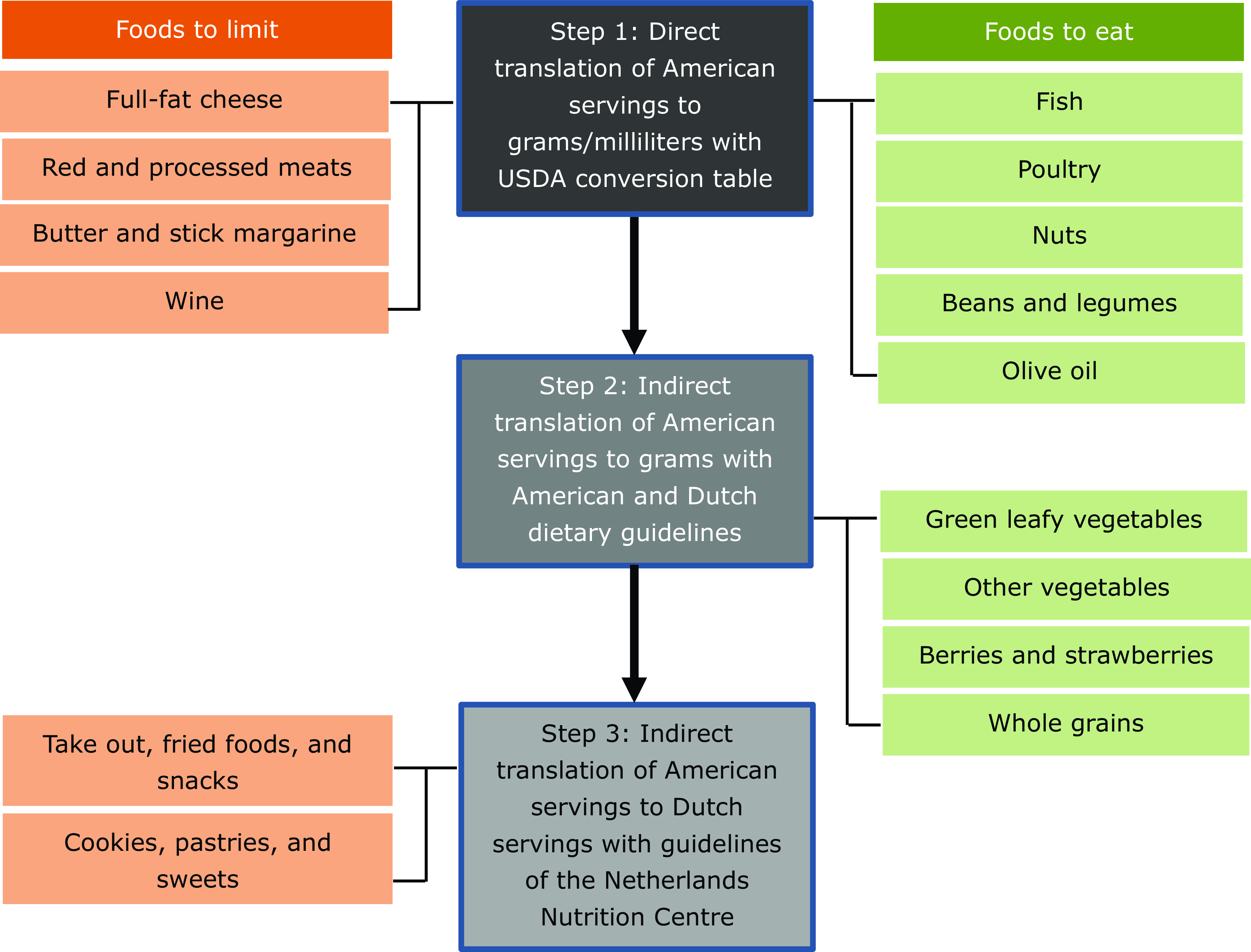

The MIND diet employs a discrete scoring system with high (1·0), moderate (0·5) and low (0·0) adherence scores per food group, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 15 points(Reference Morris, Tangney and Wang6). In the MIND-NL scoring system, we kept the scoring range from 0 to 15 points. However, quantities in weight or volume amounts rather than serving sizes were used to assess high, moderate and low adherence to the MIND-NL food groups (Table 2). This scoring in weight and volumes are in line with the Dutch Healthy Diet 2015 (DHD2015) index. The conversion from American serving sizes to weight and volumes was performed in three steps; one direct and two indirect conversion steps. The conversion steps are outlined in Fig. 1.

Table 2. Overview of the cut-off and threshold values of the MIND diet scoring v. the MIND-NL diet scoring

d, day; eq., equivalents; fl. oz., fluid ounces; g, grams; ml, millilitres; oz., ounces; tbsp, tablespoons; Tsp, teaspoons.

* Olive oil and nuts are energy-dense foods; therefore, we advise not to take excessive intakes (far beyond the cut-off values).

† Take out, fried foods and snacks serving eq. are 1 take out meal; 1 snack (fried snack or savoury pastry); four hands of crisps.

‡ Cookies, pastries and sweets serving eq. are 1 piece of cake; 1 large cookie; 4 small cookies; four pieces of chocolate; four sweet bread toppings.

§ Wine and other alcoholic beverages are both not recommended, but if consuming alcohol, then it is preferable to consume a small glass of wine (100 ml).

Note. Table left side ‘original MIND diet per week’ adapted from(Reference Liu, Morris and Dhana18).

Fig. 1. Flow chart conversion of MIND diet servings to MIND-NL diet gram equivalents corresponding to these servings.

In step 1, a direct conversion of American servings to weight or volume amounts was carried out using conversion factors. Utilizing data on serving sizes from United States Department of Agriculture and the MIND trial FFQ, we employed the United States Department of Agriculture measurement conversion to convert serving sizes (in ounces, fluid ounces, tablespoons and teaspoons) into grams (g) or millilitres (ml)(20). Serving sizes obtained from the United States Department of Agriculture FoodData Central database and the MIND trial FFQ are provided in online Supplementary Table S1. The resulting amounts in g or ml for each food group were then rounded to approximate the nearest common Dutch portion sizes. If Dutch portion sizes were given as a range, we used the minimum value. The Dutch portion sizes are presented in online Supplementary Table S1.

Indirect conversion steps were employed when the direct conversion was not feasible. Step 2 comprised an indirect translation of American servings to weight equivalents using recommendations from both the American and Dutch dietary guidelines(21,22) . In step 3, an indirect translation of American servings to Dutch servings was made using the guidelines of the Netherlands Nutrition Centre(Reference Brink, Postma-Smeets and Stafleu23).

Adaptation of the Eetscore-FFQ to assess adherence to the MIND-NL diet

We modified the Eetscore-FFQ to assess adherence to the MIND-NL diet. The Eetscore-FFQ, a short web-based FFQ designed to evaluate adherence to the Dutch dietary guidelines, encompasses fifty-five food items presented in forty questions and thirty-four corresponding sub-questions. Previous studies have demonstrated its validity in reflecting to what extent the average daily food intake adheres to the Dutch food-based Dietary Guidelines (in comparison to a full-length FFQ) and to rank participants according to their adherence levels(Reference de Rijk, Slotegraaf and Brouwer-Brolsma15). Food products were selected based on the Dutch dietary guidelines, after which these food products were aggregated into food items, based on their serving size and eating time during the day. Food items are not by definition the same as food groups. For example, the food group ‘fruit’ was also considered as one food item, but the food group ‘alcohol’ was divided into the food items ‘alcohol during the week’ and ‘alcohol during the weekend’. The order of the questions in the Eetscore-FFQ is arranged chronologically, based on foods consumed from breakfast to late evening. Typically, each question inquires about the frequency of consumption of a food group or food item, followed by the amounts consumed, specified in household measures, and, if needed the weight of the household measure. For alcohol consumption, the questionnaire distinguishes between weekdays and weekends, asking about the number of glasses consumed separately for each period, to account for potential binge drinking, as intakes can significantly differ between weekdays and weekend.

To modify the Eetscore-FFQ, we evaluated the food items and questions for completeness in assessing the MIND-NL diet adherence. We evaluated whether all MIND specific food products were examined, whether existing food items differentiated the specific MIND diet food groups in enough detail (e.g. vegetables and cooking oils), and whether the correct frequency of intake was questioned.

The MIND-NL scores (0, 0·5 and 1) per food group and the total MIND-NL diet score are automatically computed, with a maximum score of fifteen points utilising an R-script (RStudio Version 1.4.1717), which underlies the web-based Eetscore tool. This R-script calculates the daily consumed amounts in weights or volumes by combining the questions about frequency of consumption and amounts consumed of a food item. Food items are grouped based on the criteria of the MIND-NL food groups (Table 1). The scoring, as presented in Table 2, is incorporated within the R-script to calculate the MIND-NL score.

Results

Modifying food groups and food products to fit the MIND-NL diet

We found a significant overlap between the MIND diet food groups and food groups outlined in the Dutch dietary guidelines(Reference Morris, Tangney and Wang6,Reference de Rijk, Slotegraaf and Brouwer-Brolsma15,Reference Kromhout, Spaaij and de Goede17) . The food groups that showed direct overlap were whole grain products, legumes, nuts, fish, red and processed meat. A total of nine MIND diet food groups were included in larger food groups of the Dutch dietary guidelines: green leafy vegetables and other vegetables were included in the food group ‘vegetables’, berries in the food group ‘fruit’, olive oil and butter and margarines in the food group ‘fats and oils’, cheese in the food group ‘dairy products’, fast fried foods and pastries and sweets in the group ‘unhealthy choices’ and wine in the food group ‘alcohol’. Only poultry was not represented by one of the food groups of the Dutch dietary guidelines, but was identified in the Dutch National Food Consumption Survey as a frequently consumed food group(Reference Van Rossum, Buurma-Rethans and Dinnissen19).

We adjusted the names of the MIND food groups ‘fast fried foods’, ‘pastries and sweets’, ‘red meats and products’, ‘cheese’ and ‘berries’ to improve alignment with the terminology used in the Dutch dietary guidelines and language (see Table 1). Furthermore, we reclassified wine from a recommended to a non-recommended food group. According to the Dutch dietary guidelines, it is advised to not consume alcohol or limit alcohol consumption to 10 g/d to reduce the risk of cancer and other diseases. Although this advice does not specifically apply to dementia, the MIND-NL score is designed for use in both observational and intervention studies. Therefore, it is not ethical to advise non-alcoholic drinkers to start drinking wine.

Food products, based on the MIND food groups, were selected based on their consumption in the Netherlands, as determined by the Dutch National Food Consumption Survey, and are listed in Table 1.

Development of the MIND-NL diet scoring system

For nine out of fifteen MIND food groups the United States Department of Agriculture measurement serving sizes could be employed for a direct translation of serving sizes to weight or volume equivalents (fish; poultry; nuts; butter and stick margarine; full-fat cheese; red and processed meat; beans and legumes; wine and olive oil). For four out of fifteen MIND food groups both American and Dutch dietary guidelines were used for an indirect translation (green leafy vegetables; other vegetables; berries and whole grains). For two out of fifteen MIND food groups no translation to weight or volume equivalents could be made, but rather serving equivalents were implemented (take out, fried foods, and snacks; cookies, pastries and sweets).

Due to the considerable variety of food products within the MIND food groups for green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, berries and whole grains, it was not feasible to directly translate cups into grams. Instead, these food groups were indirectly translated with use of the Dutch and the American food-based dietary guidelines(21,22) . Regarding total vegetable intake, the original MIND diet suggests consuming green leafy vegetables and other vegetables in a 1:1 ratio (cooked). Applying this ratio, in combination with the Dutch food-based dietary guidelines of vegetables, resulted in a recommended daily intake of 100 g for both green leafy vegetables and other vegetables. As no specific guidelines exist for the intake of berries, guidelines for total fruit intake were considered for the conversion of servings to grams. American guidelines recommend a daily fruit intake of two cups, while the Dutch dietary guidelines recommend 200 g of fruit per day. On the assumption that one cup of berries equals on average 100 g, we translated a serving of berries of 0·5 cup, into 50 g. The Dutch food-based dietary guideline for whole grains is 90 g/d. The MIND diet recommends an intake of three servings per day, which corresponds to three slices of wholegrain bread, 1·5 cup of wholegrain pasta/brown rice, or 2·25 cups of whole grain cereals(Reference Liu, Morris and Dhana18). This advice aligns with the Dutch advise of 90 g/d, which is approximately equal to three slices of bread, two serving spoons of wholegrain pasta or 1·5 serving spoon of brown rice (Table 2, online Supplementary Table S1)(24).

The MIND food groups ‘fast and fried foods’ and ‘pastries and sweets’ were aligned to the recommendations of the Netherlands Nutrition Centre for ‘unhealthy choices’(Reference Brink, Postma-Smeets and Stafleu23). The Netherlands Nutrition Centre recommends limiting consumption of unhealthy choices to a maximum of three serving equivalents per week. For the MIND-NL scoring system, we divided the three serving equivalents of unhealthy choices into a maximum of one serving equivalent of ‘take-out, fried foods or savoury snacks’ and two serving equivalents of ‘cookies, pastries and sweets’. A serving equivalent of ‘take-out, fried foods and snacks’ includes 1 take-out meal; 1 fried snack; 1 savoury pastry; or four handfuls of crisps. A serving equivalent of ‘cookies, pastries and sweets’ includes one piece of cake; one large cookie; four small cookies; four chocolates or four sweet bread toppings (Table 2, online Supplementary Table S1)(Reference de Rijk, Slotegraaf and Brouwer-Brolsma15).

Table 2 shows an overview of the cut-off and threshold values of the MIND diet scoring, determined based on the described steps. Online Supplementary Table S1 provides a detailed tabular representation of data used for the three conversions steps, including the used conversion factors, Dutch and American guidelines and standardised Dutch serving sizes in grams and millilitres.

Adaptation of the Eetscore-FFQ to assess adherence to the MIND-NL diet

During the modification of the Eetscore-FFQ to the MIND-NL-Eetscore-FFQ, seventeen additional food items and one question regarding the frequency of consuming fried or take-out meal were included. This resulted in the MIND-NL-Eetscore-FFQ, consisting of seventy-two food items, forty-one questions, and forty-five sub-questions. The newly added food items were specific to the MIND diet and differentiated the types of cheese (low- and high-fat cheese), (pea)nut butter as a bread topping, green leafy vegetables, cooking fats (stick margarine and olive oil), berries and strawberries, wine, and take-out and fried foods. Additionally, the intake of beans and legumes was specified in terms of frequency per week rather than per month. The MIND-NL-Eetscore-FFQ captures the results of both the original Eetscore and the MIND-NL diet score. However, for calculating the MIND-NL score, only forty-six food items and twenty-seven questions are relevant.

Discussion

This article describes a reproducible workflow comprising three steps to modify the MIND diet scoring system, converting consumed amounts from serving sizes to weights or volume amounts, while considering cultural dietary habits. By incorporating commonly consumed Dutch food products, guidelines and household measures, the conversion resulted in a Dutch version of the MIND adherence score (MIND-NL). Furthermore, this paper describes the adaptation of the existing Eetscore-FFQ into an MIND-NL-Eetscore-FFQ, thus designing a tailored assessment method for evaluating adherence to the MIND-NL diet.

The MIND diet and scoring system have been tailored to the Dutch context, with the aim to remain closely aligned to the original MIND diet score. However, some adjustments were necessary to maintain consistency with Dutch dietary habits and Dutch food-based dietary guidelines(Reference Kromhout, Spaaij and de Goede17,Reference Van Rossum, Buurma-Rethans and Dinnissen19) . A specific aspect of Dutch dietary habits is the frequent consumption of bread with various toppings, such as cheese, deli meats and peanut butter. In line with Dutch dietary guidelines, recommending reduced saturated fat intake, the MIND-NL advice includes the substitution of high-fat cheese with low-fat alternatives. Additionally, in the Netherlands all deli meats are classified as processed meats(25). Therefore, we transferred all deli meats, including roast cooked chicken or turkey deli meats, to the MIND-NL group of processed meats. Take-out foods, fried foods, snacks, cookies, pastries and sweets are classified as unhealthy choices, with their scoring based on serving equivalents (maximum 3 per week), which is in line with the Netherlands Nutrition Centre recommendations. Wine was adjusted to no glass or a maximum of one glass of 100 ml/d, in accordance with Dutch dietary guidelines recommending a maximum alcohol intake of 10 g/d, to reduce the risk of cancer(Reference Kromhout, Spaaij and de Goede17).

Reclassifying wine to a non-recommended food group and subsequently changing the cut-off values of the wine component might influence the scoring. Within the original MIND diet not drinking wine scores the minimum score of 0 points, whereas in the MIND-NL diet these non-drinkers receive the maximum score of 1 point. However, it is important to note that the scoring of the wine component already differs across studies, complicating comparison of this specific component. Some studies excluded the wine component completely(Reference Huang, Tao and Chen26–Reference Barnes, Dhana and Liu30), while other studies changed the cut-off values(Reference Shakersain, Rizzuto and Larsson31–Reference Zhang, Cao and Li34). Strikingly, RUSH University, the university that developed the MIND diet, excluded the wine component in their MIND diet trial(Reference Barnes, Dhana and Liu30). Taking into account dose–response meta-analyses, which showed that an increased risk of dementia and mild cognitive performance was associated with alcohol intake of more than one glass per day, we suggest an adaptation to the MIND diet food group of wine, as already implemented in the MIND-NL diet(Reference Lao, Hou and Li35,Reference Xu, Wang and Wan36) .

As aforementioned, we changed the original name of the food group ‘cheese’ to ‘high-fat cheese’. We expect that this adjustment does not deviate from the intended concept of the MIND diet to reduce intake of saturated fatty acids. The MIND diet trial, conducted by the developers of the MIND diet, also referred to ‘whole fat cheese’ in their protocol(Reference Barnes, Dhana and Liu30). Given the high availability of low-fat cheese in the Netherlands, we chose to specify this cheese group in more detail for the Dutch context. Since it is often unclear which specific food products are included in MIND diet studies, due to lack of mentioning, we cannot elucidate the impact of this change in comparison with other studies.

Throughout the process it became evident that not all food groups could be directly quantified to weights or volumes, for which indirect methods had to be used. For the indirect translation of food groups (green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, berries and strawberries, whole grains, take-out foods, fried foods and snacks, cookies, pastries and sweets), the Dutch food-based dietary guidelines were used as a basis, resulting in slight differences in weights as compared with the original MIND diet, which was developed in the USA. Employing MIND scores based on quantities in weight or volume amounts could reveal discrepancies in evaluating MIND diet exposure. These discrepancies in MIND diet scores may explain the inconsistent findings observed in articles studying the MIND diet in relation to brain health outcomes(Reference van Soest, Beers and van de Rest5). Moreover, utilizing a quantity-based scoring system facilitates the implementation of other dietary assessment methods to determine MIND adherence.

As explained above, certain changes had to be made for the development of the MIND-NL diet, rendering it not fully comparable with the MIND diet. Cultural adaptations, beyond metric discrepancies, are inevitable in food-based dietary patterns due to variations in the availability of food products and cooking practices across countries. These differences inherently affect the comparability of dietary patterns between countries. While it is impossible to completely capture these differences, it is recommended to report any known modifications to the considered food products to ensure transparency. By knowing what changes have been made, researchers can assess the impact on comparability.

Furthermore, culturally adapted MIND diet scores should adequately capture nutrients important for brain health. The original article of Morris et al. (2015) highlights the importance of reducing intakes of saturated and trans fatty acids and increasing intakes of B-vitamins, carotenes, vitamin D and n-3 fatty acids(Reference Morris, Tangney and Wang6). Therefore, construct validation should be performed to confirm that the original diet’s essential nutrients for brain health are maintained.

In light of the international interest in the MIND diet to reduce cognitive decline, the MIND diet has already been adapted in different countries. For instance, in China the cMIND diet was developed. The developers of the cMIND stated that the original MIND diet predominantly features Western foods, thus limiting its application in China. The cMIND diet comprises 12 food groups, based on commonly eaten foods in China. The cMIND diet incorporates additional components such as mushrooms/algae, fresh fruit, garlic, and tea. However, the cMIND diet excludes certain food groups present in the original MIND diet, including green leafy vegetables, berries, poultry, wine, butter and margarine, cheese, red and processed meat, as well as fast and fried foods. The cMIND diet scoring is still based on servings, lacking information about gram equivalents of servings(Reference Huang, Aihemaitijiang and Ye27). In France, the MIND diet was adapted to French dietary habits and guidelines, resulting in changed component thresholds. Due to low berry consumption as shown in the study of Thomas et al. (2022), the berry component was replaced with a polyphenol component. While the scoring system was primarily based on servings, exceptions were made for polyphenols and green leafy vegetables. A disparity was found between green leafy vegetables in the MIND-NL diet and the French-adapted MIND diet. The maximum score for the green leafy vegetable component within the MIND-NL diet was achieved with an intake of ≥100 g/d, whereas for the French-adapted diet, this was >60 g/d(Reference Thomas, Lefevre-Arbogast and Feart32). Some other studies retained all the original MIND components, but changed the scoring of adherence to study population tertiles, making external validity difficult(Reference van Soest, Beers and van de Rest5,Reference Rostami, Parastouei and Samadi37,Reference Salari-Moghaddam, Keshteli and Mousavi38) .

MIND diet scores in previous studies were evaluated using FFQ ranging from ninety-eight to 183 items, whereas the Dutch MIND-NL-Eetscore-FFQ contains seventy-two items only, making it a more time-efficient (+/– 20 min) method to assess the MIND diet(Reference van Soest, Beers and van de Rest5). Moreover, the section relevant to the MIND-NL diet is even more concise and comprises only forty-six items. We think that measuring scores for both adherence to the Dutch dietary guidelines (fifty-five items) and to MIND-NL diet (forty-six items) simultaneously is of added value for future research.

The original food items included in the Eetscore-FFQ showed an acceptable ranking ability and good reproducibility for determining adherence to the Dutch food-based dietary guidelines(Reference de Rijk, Slotegraaf and Brouwer-Brolsma15). The relative validity of the MIND-NL-Eetscore-FFQ ought to be assessed in a forthcoming study, as compared with one of the standard dietary assessment methods, such as a comprehensive FFQ or food records. Similar to the Eetscore-FFQ, the MIND-NL-Eetscore-FFQ evaluates dietary adherence. However, as not all foods are queried, total energy and nutrient intake cannot be established from the questionnaire. Its utility lies in monitoring scores over time or ranking participants accordingly(Reference de Rijk, Slotegraaf and Brouwer-Brolsma15).

In conclusion, we reported a stepwise approach for the adaptation of the MIND diet to a scoring system using quantities in weight or volume amounts, rather than serving sizes and reported the culturally based adjustments made to the scoring. Subsequently, we adapted the existing Eetscore-FFQ into a MIND-NL-Eetscore-FFQ, enabling assessment of MIND-NL diet adherence. The next step is to validate both the MIND-NL score (construct validity), as well as the MIND-NL Eetscore-FFQ (relative validity).

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors’ contributions were as follows – S. B., S. H., L. G., M. S., J. V. and O. R. designed the research; S. B., S. H., H. J. and J. V. translated the MIND diet into the MIND-NL diet, and developed the MIND-NL-Eetscore-FFQ; S. B., S. H. wrote the manuscript and all authors had responsibility for the final content and read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare no relevant conflict of interest to disclose.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114524001892