Endometrial cancer represents the 6th most commonly diagnosed malignancy among women, with over 417 000 new cases and 97 000 deaths in 2020(Reference Sung, Ferlay and Siegel1).

Endometrial cancer primarily affects post-menopausal women(Reference Lortet-Tieulent, Ferlay and Bray2). The use of oestrogenic hormone replacement therapy (HRT)(Reference Tempfer, Hilal and Kern3), obesity(Reference Hopkins, Goncalves and Cantley4–Reference Lauby-Secretan, Scoccianti and Loomis6) and physical inactivity(Reference Kerr, Anderson and Lippman5,Reference Friedenreich, Cust and Lahmann7,Reference Shen, Mao and Liu8) represent the main modifiable risk factors for the disease. With the ageing of the population and the rising prevalence of obesity and sedentary lifestyle, the burden of endometrial cancer is expected to increase globally(Reference Lacey, Chia and Rush9); primary prevention of this neoplasm is therefore of paramount importance.

Dietary habits may influence endometrial cancer. High glycaemic load diet(Reference Hatami Marbini, Amiri and Sajadi Hezaveh10,Reference Turati, Galeone and Augustin11) and high consumption of red and processed meat(Reference Rosato, Negri and Parazzini12–Reference Dunneram, Greenwood and Cade14) have been associated with the disease, while high consumption of coffee(Reference Lukic, Guha and Licaj15–Reference Bravi, Scotti and Bosetti17), fibres(Reference Chen, Zhao and Li18,Reference Li, Mao and Yu19) , fruit(Reference Bandera, Kushi and Moore20) and vegetables(Reference Bandera, Kushi and Moore20–Reference Turati, Rossi and Pelucchi22) may reduce the risk. However, evidence on dietary factors is still controversial(Reference Biel, Csizmadi and Cook23).

In 2007, the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) published the following evidence-based recommendations aimed at cancer prevention: (1) be as lean as possible within the normal range of body weight, (2) be physically active as part of everyday life, (3) limit consumption of energy-dense foods, (4) eat mostly foods of plant origin, (5) limit intake of red meat and avoid processed meat, (6) limit consumption of alcoholic drinks, (7) limit consumption of salt and avoid mouldy cereals or pulses, (8) avoid dietary supplements for cancer prevention, and (9) breastfeed(Reference Wiseman24). In 2018, recommendations were updated with minor changes, including the avoidance of any alcohol and the avoidance of sugar-sweetened drinks as a separate recommendation(Reference Clinton, Giovannucci and Hursting25). The 2007 recommendations on limiting salt consumption and avoiding mouldy cereals or pulses were removed in the 2018 version, as these are specific for selected populations.

In several cohort, case–control and cross-sectional studies, adherence to the WCRF/AICR recommendations was associated with reduced total and cardiovascular mortality(Reference Vergnaud, Romaguera and Peeters26), and reduced risks of overall(Reference Vergnaud, Romaguera and Peeters26–Reference Korn, Reedy and Brockton28) and selected cancers, including those of the breast(Reference Turati, Dalmartello and Bravi29–Reference Barrios-Rodriguez, Toledo and Martinez-Gonzalez32), colorectum(Reference Petimar, Smith-Warner and Rosner33–Reference Kenkhuis, van der Linden and Breedveld-Peters39), pancreas(Reference Zhang, Li and Hao40,Reference Lucas, Bravi and Boffetta41) , prostate(Reference Olmedo-Requena, Lozano-Lorca and Salcedo-Bellido42), and upper aerodigestive tract(Reference Bravi, Polesel and Garavello43). However, to our knowledge, no previous investigation has analysed the association of adherence to these recommendations with the occurrence of endometrial cancer.

In the current study, we evaluated whether adherence to the WCRF/AICR cancer prevention recommendations may affect endometrial cancer risk using data from a multicentric case–control study conducted in Italy.

Materials and methods

Study population and data collection

We analysed data from a hospital-based case–control study on endometrial cancer conducted between 1992 and 2006 in three Italian areas, that is, the greater Milan area, the provinces of Udine and Pordenone in northern Italy and the urban area of Naples in southern Italy(Reference Bravi, Bertuccio and Turati44,Reference Rossi, Edefonti and Parpinel45) . Cases were 454 women (median age 60 years, range 18–79) diagnosed with incident histologically confirmed endometrial cancer according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM, code 182·0), admitted to major teaching and general hospitals of the study areas. Women diagnosed with endometrial cancer up to a year earlier and with no prior diagnosis of cancer were eligible. Controls were 908 women (median age 61 years, range 19–79) admitted to the same hospital network as cases for acute, non-neoplastic conditions, unrelated to long-term dietary modifications, that is, traumas (36 %), orthopaedic disorders (32 %), acute surgical conditions (9 %) and miscellaneous illnesses including eye, nose, ear, or skin disorders (23 %). Women with a history of hysterectomy or admitted for gynaecological or hormone-related conditions were excluded from the control group. Cases and controls were frequency matched by 5-year age group and study centre; we used a case to control ratio of 1:2 to increase the statistical power of the study. Comprising over 450 cases and 900 controls, our study has ∼90 % power to detect as statistically significant (at α = 0·05) an odds ratio (OR) equal or greater than 1·5 for an exposure with a prevalence of 25 % in controls. Matching was achieved by sampling as controls twice the number of cases in each 5-years age group. This was done by periodically checking the age distribution of cases within each participating centre. More than 95 % of eligible cases and a similar proportion of controls agreed to participate in the study and completed the questionnaire. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Board of Ethics of each participating centre. Informed consent was obtained from all enrolled women.

Patients were interviewed by centrally trained personnel during their hospital stay using a standard structured questionnaire collecting information on socio-demographic characteristics and anthropometric measures (including self-reported weight before diagnosis/hospital admission), selected lifestyle habits (i.e., tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, and physical activity), personal medical history of selected diseases, family history of cancer in first-degree relatives, menstrual and reproductive factors, and use of oral contraceptive and HRT. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height2 (kg/m2). Occupational and leisure time physical activities at ages 12, 15–19, 30–39, and 50–59 were self-reported. Occupational physical activity was classified, based on the type of job, as sedentary (e.g., office worker, student), standing (e.g., shop assistant, teacher, laboratory worker), intermediate (e.g., waiter, cook, kindergarten teacher, housewife doing housework), heavy (e.g. farmer, heavy industry worker), and very heavy (e.g., construction bricklayer, athlete). As for leisure time physical activity, we asked subjects to report their usual number of hours of physical activities (including sport, cycling, etc.) per week (i.e., > 7, 5–7, 2–4, and < 2).

Information regarding the usual diet in the 2 years before cancer diagnosis (for cases) or hospital admission (for controls) was retrieved using a reproducible(Reference Franceschi, Barbone and Negri46,Reference Franceschi, Negri and Salvini47) and valid(Reference Decarli, Franceschi and Ferraroni48) food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) including seventy-eight food items or food groups and, for about half of them, their usual portion size. Subjects were asked to indicate their average weekly consumption of each item in the past 2 years. Intake of non-alcohol energy and selected nutrients was determined using an Italian food composition database(Reference Gnagnarella, Parpinel and Salvini49).

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research score

We calculated a score measuring adherence to the 2018 version of the WCRF/AICR recommendations according to standard criteria proposed by Shams-White et al. (Reference Shams-White, Brockton and Mitrou50,Reference Shams-White, Romaguera and Mitrou51) . We included seven of eight recommendations, that is, (1) be at a healthy weight, (2) be physically active, (3) eat a diet rich in vegetables, fruits and wholegrains, (4) limit consumption of fast foods and other processed foods high in fat, starches or sugars, (5) limit consumption of red and processed meat, (6) limit consumption of sugar sweetened, and (7) avoid consumption of alcohol. The recommendation number 3 was split into two sub-recommendations (as also suggested by the standard scoring system(Reference Shams-White, Brockton and Mitrou50,Reference Shams-White, Romaguera and Mitrou51) ): one on vegetables and fruits (3a) and one on wholegrains (3b). The optional recommendation on breast feeding was not included. For each recommendation, participants were assigned 1 point for complete adherence, 0·5 for partial adherence, and 0 for non-adherence. For the two sub-recommendations (i.e., 3a and 3b), participants were assigned 0·5 points for complete adherence, 0·25 for partial adherence, and 0 for non-adherence; points on the two sub-recommendations were, then, summed up. Complete, partial, and non-adherence to the recommendations were defined, respectively, as follows: (1) BMI: 18·5–24·9, 25–29·9, < 18·5, or ≥ 30 kg/m2 (data on waist circumference were not considered since the information was available only for a subset of women); (2) physical activity: very heavy/heavy job or ≥ 5 h/week of leisure time physical activity, medium job and ≤ 4 h/week of leisure time physical activity or standing/sedentary job and 2–4 h/week of leisure time physical activity, sedentary job and < 2 h/week of leisure time physical activity; (3a) consumption of vegetables and fruits: ≥ 400, 200–< 400, < 200 g/diet; (3b) consumption of wholegrains: ≥ 30, 15–< 30, < 15 g/diet; (4) consumption of energy-dense foods (as a proxy for the consumption of fast foods and other processed foods high in fat, starches or sugars): ≤ 523·0, 523·0–< 732·2, ≥ 732·2kJ/100 g/diet; (5) consumption of red and processed meat: red and processed meat < 500 and processed meat < 21 g/week, red and processed meat < 500 and processed meat 21–< 100 g/week, red and processed meat ≥ 500 or processed meat ≥ 100 g/week; (6) consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks: 0, > 0–≤ 250, > 250 g/week and (7) consumption of alcohol: 0, > 0–≤ 7, > 7 drinks/week (see details in online Supplementary Table S1). The overall WCRF/AICR score was obtained as the sum of the points assigned to each recommendation; its theoretical range is from 0 to 7, with higher values indicating greater adherence to the WCRF/AICR recommendations. We also derived a dietary WCRF/AICR score summing up only the five recommendations regarding dietary habits (i.e., eat a diet rich in vegetables, fruits and wholegrains; limit consumption of fast foods and other processed foods high in fat, starches or sugars; limit consumption of red and processed meat; limit consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages; and avoid consumption of alcohol); its theoretical range is from 0 to 5.

Statistical analysis

We derived the OR of endometrial cancer and the corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CI) according to each WCRF/AICR recommendation (in three categories for complete, partial, and non-adherence), to the overall WCRF/AICR score (in approximate quartiles calculated among controls, i.e., < 3·25, 3·25–3·99, 4·00–4·49, ≥ 4·50, as well as for one-point increment) and to the dietary WCRF/AICR score (in approximate tertiles among controls: < 2·25, 2·25–2·99, ≥ 3·00, as well as for one-point increment). We used multiple (adjusted) logistic regression models, conditioned on 5-year age group and centre, and including terms for years of education, year of interview, smoking, history of diabetes, total energy intake, age at menarche, parity, menopausal status, use of oral contraceptive and HRT. When assessing the association of single recommendations and the dietary WCRF/AICR score, we included in the model as adjustment factors terms for BMI (in categories: < 21·00, 21·00–25·99, 26·00–29·99, ≥ 30 kg/m2, except for the analysis on the recommendation on body fatness) and occupational and leisure time physical activity (in categories defined as the recommendation on physical activity included in WCRF score, except for the analysis on the corresponding recommendation). A few missing data on adjustment factors were replaced by the median value (continuous variables) or mode category (categorical variables) according to case/control status. In sensitivity analyses, we excluded alternately each recommendation at a time from the overall WCRF/AICR score in order to evaluate the relative impact of the single recommendations included in the score, and we re-ran the main analysis with a complete case approach.

Additionally, we estimated the OR for one-point increment in the WCRF/AICR score across strata of age, BMI, menopausal status, parity, oral contraceptive and HRT use. Heterogeneity across strata was tested by a likelihood ratio test comparing the models with and without the interaction term between the subgroup factor and the WCRF/AICR score variable. For the likelihood ratio test, we considered as significant a P-value < 0·10.

All the analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Results

Table 1 shows the distribution of selected characteristics of endometrial cancer cases and controls. By design, cases and controls had a similar age and were hospitalised in the same centres. Compared with controls, cases had a higher BMI, reported more frequently a history of diabetes and had lower parity; they also tended to report more frequently HRT use and less frequently oral contraceptive use. No differences emerged according to the other factors considered. In our database, the WCRF/AICR score ranged from 0·5 to 6·5.

Table 1. Distribution of endometrial cancer cases and controls according to selected covariates, Italy, 1992–2006

(Numbers and percentages; mean values and standard deviations)

WCRF, World Cancer Research Fund.

* 4 (0·4 %) missing values among controls.

† 11 (2·4 %) missing values among cases and 8 (0·8 %) among controls.

Table 2 provides the OR of endometrial cancer for each recommendation included in WCRF/AICR score. Complete adherence (i.e., 1 point) to the recommendation on body fatness reduced the risk of endometrial cancer by 72 % (OR = 0·28, 95 % CI 0·20, 0·39 v. non-adherence, P-value for trend < 0·001). There was an inverse association with adherence to the recommendation on red and processed meat (OR for complete v. non-adherence = 0·50, 95 % CI 0·24, 1·03, P for trend = 0·013). No significant association was found for adherence to the other recommendations.

Table 2. Asssociation between adherence to each recommendation included in the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) score and endometrial cancer risk, Italy, 1992–2006

(Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals; numbers and percentages)

* Estimated from logistic regression models conditioned on age and centre and including terms for year of interview, education, BMI, physical activity, smoking, total energy intake, history of diabetes, age at menarche, menopausal status, parity, use of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy, unless the variable was part of the recommendation under evaluation.

† The sum does not add up to the total because of missing data.

‡ Reference category.

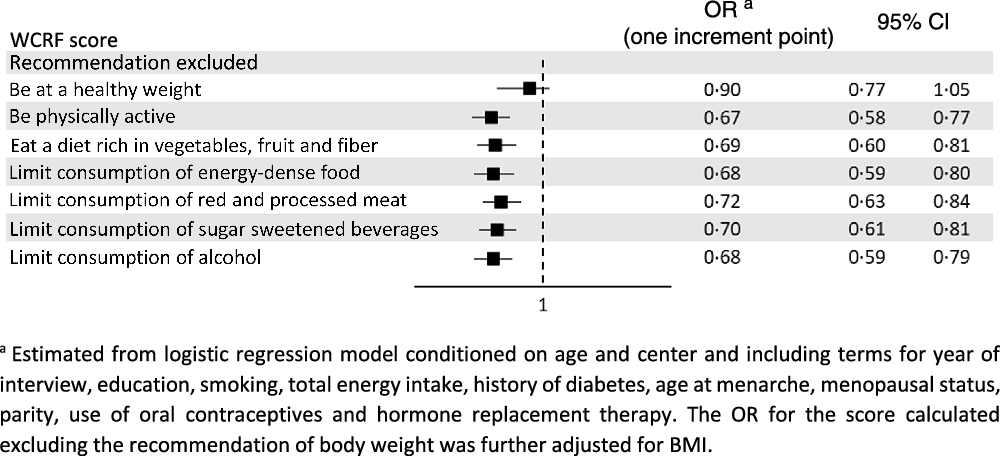

Table 3 shows the OR of endometrial cancer according to the overall WCRF/AICR score and the dietary WCRF/AICR score. After allowing for major confounders, high adherence to the WCRF/AICR recommendations was inversely related to the risk of endometrial cancer, with an OR of 0·42 (95 % CI 0·30, 0·61) for the highest compared with the lowest score quartile (P-value for trend < 0·001). The OR for one-point increment in the WCRF/AICR score was 0·72 (95 % CI 0·63, 0·83). As for the dietary WCRF/AICR score, the OR for the highest compared with the lowest tertile was 0·67 (95 % CI 0·46, 0·96, P-value for trend = 0·017), and that for one-point increment was 0·81 (95 % CI 0·68, 0·96). Results were virtually identical when using a complete case approach (OR = 0·42, 95 % CI 0·29, 0·60 for the highest compared with the lowest overall WCRF/AICR score quartile; OR = 0·66, 95 % CI 0·47, 0·94 for the highest compared with the lowest dietary WCRF/AICR score tertile). The inverse association with the overall WCRF/AICR score was consistent after the exclusion alternately of each recommendation on diet and physical activity at a time (Fig. 1). When the recommendation on body fatness was excluded, the association was reduced (OR for one-point increment = 0·90, 95 % CI 0·77, 1·05).

Table 3. Association of the overall World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) score and the WCRF/AICR diet score with endometrial cancer risk, Italy, 1992–2006

(Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals; numbers and percentages)

* Estimated from logistic regression models conditioned on age and centre and including terms for year of interview, education, smoking, total energy intake, history of diabetes, age at menarche, menopausal status, parity, use of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy. OR according to the WCRF/AIRC diet score were further adjusted for BMI and physical activity.

† Reference category.

Fig. 1. Odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95 % confidence interval (CI) of endometrial cancer for one-point increment in the overall World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) score excluding alternately each recommendation at a time, Italy, 1992–2006.

In subgroup analyses (Table 4), the association was stronger among women with a normal weight, those who were older, and consequently those in post-menopause and those with ≥ 2 children.

Table 4. Association between the overall World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) score and endometrial cancer risk in strata of selected covariates, Italy, 1992–2006

(Odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

* Estimated from logistic regression models conditioned on age and centre and including terms for year of interview, education, smoking, total energy intake, history of diabetes, age at menarche, menopausal status, parity, use of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy, unless the variable was the stratification factor.

† OR of endometrial cancer for the WCRF/AICR score excluding BMI: (1) < 25: 0·78 (95 % CI 0·59, 1·02), (2) 25–29: 0·92 (95 % CI 0·72, 1·19) and (3) ≥ 30: 1·13 (95 % CI 0·80, 1·59).

Discussion

In this large, multicentric Italian study, greater adherence to the WCRF/AICR preventive cancer recommendations on body fatness, physical activity, and diet was associated with an approximately 60 % reduced risk of endometrial cancer. As expected(Reference Parazzini, La Vecchia and Bocciolone52), body weight had the strongest influence on the risk; however, a score measuring adherence to the recommendations related to diet was inversely associated with the risk of endometrial cancer after adjusting for BMI. In addition, the inverse relation was stronger in normal weight women, reflecting the key role of overweight and obesity on endometrial cancer risk(Reference Parazzini, La Vecchia and Bocciolone52).

Maintaining a healthy weight throughout life – of specific importance for endometrial cancer risk – being physically active, following a healthy eating pattern and avoiding alcohol use are the key recommendations for the prevention of cancer, also according to the American Cancer Society(Reference Kushi, Doyle and McCullough53,Reference Rock, Thomson and Gansler54) .

Our results on body fatness reflect the well-established and strong association between overweight, obesity and endometrial cancer risk. Obesity (defined as BMI > 30 or < 35 kg/m2) is associated with an over 2-fold increase in the risk of endometrial cancer and severe obesity (defined as BMI > 35 kg/m2) with a 5-fold increase(Reference Shaw, Farris and McNeil55). The relationship involves the hyper-oestrogenic state of obesity(Reference Kitson and Crosbie56), besides other mechanisms. Adipose tissue, functioning as an important endocrine organ, contributes to hormone production (such as oestrogens), maintenance of a pro-inflammatory state, and stimulation of cellular proliferation pathways. Such factors play a key role in carcinogenesis and endometrial proliferation. In addition, adiposity influences the metabolism and is associated with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia, well-recognised risk factors for the endometrial cancer(Reference Orgel and Mittelman57). Intentional weight loss (self-reported or after bariatric surgery) and maintaining a stable weight were related to a significantly lower risk of endometrial cancer (relative risk ranging from 0·61 to 0·96)(Reference Zhang, Rhoades and Caan58). A study conducted in a cohort of severely obese women undergoing a weight loss intervention including diet and physical activity found that levels of cancer-associated biomarkers could be normalised with weight loss(Reference Linkov, Maxwell and Felix59).

As for physical activity, the WHO(Reference Bull, Al-Ansari and Biddle60) and the US Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory committee(61), on the basis of their appraisal of a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, reported a moderate to high-certainty evidence that high physical activity levels are associated with a reduction in endometrial cancer risk. A systematic review and meta-analysis(Reference Schmid, Behrens and Keimling62) reported a significant inverse association between physical activity and endometrial cancer among overweight or obese women only, possibly due to the counterbalance function of physical activity against the unfavourable effects of obesity and the different composition of body mass. Further, since physical activity and BMI are strongly linked, when the benefit from physical activity in preventing endometrial cancer has been explored using a mediation analysis, it appeared that the majority of the protective role was mediated through a reduction in the risk of obesity(Reference Saint-Maurice, Sampson and Michels63). Other mechanisms involved may be the decreasing oestrogens through reducing peripheral adipose tissue where the conversion of androgens to oestrogens occurs(Reference Kaaks, Lukanova and Kurzer64), the improvement of insulin sensitivity(Reference Mann, Beedie and Balducci65), the alteration of the insulin-like growth factor axis(Reference Gatti, De Palo and Antonelli66), and the reduction of pro-inflammatory mediators(Reference Bruunsgaard67). We measured adherence to the recommendation on physical activity combining available questionnaire data on the level of physical activity at work and on the time spent in leisure time physical activity at age 30–39 years and adapted cut points for adherence proposed by the standard scoring system, which were expressed as min/week of moderate-vigorous physical activity, to our physical activity variable. With such an approach, less than 10 % of cases and controls were categorised as ‘non-adherent’, and we did not find any relevant association with endometrial cancer. Whether higher levels of physical activity may favourably affect endometrial cancer risk cannot be excluded.

As for the WCRF/AICR recommendations on diet, various studies showed a favourable role of dietary fibre(Reference Chen, Zhao and Li18,Reference Li, Mao and Yu19) , fruit(Reference Bandera, Kushi and Moore20), and vegetables(Reference Bandera, Kushi and Moore20–Reference Turati, Rossi and Pelucchi22) on endometrial cancer risk. Vegetables and fruit represent a source of a variety of micronutrients and other bioactive constituents that may protect from cancer through modulation of steroid hormone concentration and metabolism, antioxidant activities, modulation of detoxification enzymes, and stimulation of the immune system(Reference Lampe68). As for dietary fibres, the favourable role may be attributable to the decrease in plasma cholesterol levels and in postprandial glycaemia, and the bacterial fermentation of fibre to short-chain fatty acids(Reference Slavin69). Conversely, the intake of red and processed meat was directly associated with endometrial cancer risk in some(Reference Rosato, Negri and Parazzini12–Reference Dunneram, Greenwood and Cade14), but not all studies(Reference Bravi, Scotti and Bosetti21,Reference Cross, Leitzmann and Gail70) ; alcohol intake was not appreciably associated with the disease(Reference Fedirko, Jenab and Rinaldi71,Reference Turati, Gallus and Tavani72) and the few studies investigating sugar-sweetened beverage consumption(Reference Dunneram, Greenwood and Cade14,Reference Arthur, Kirsh and Mossavar-Rahmani73,Reference Inoue-Choi, Robien and Mariani74) gave inconsistent results. In our study, a score reflecting adherence to a dietary pattern characterised by high consumption of vegetables, fruit and wholegrains and low consumption of energy-dense food, red and processed meat and sugar-sweetened and alcoholic drinks reduced the risk of endometrial cancer. Along this line, previous studies found inverse associations with healthy eating behaviours, including the Mediterranean diet(Reference Filomeno, Bosetti and Bidoli75–Reference Zhang, Li and Tan77) and, more recently, a diet for diabetes prevention(Reference Esposito, Bravi and Serraino78), and direct associations with Western-style dietary patterns(Reference Si, Shu and Zheng79,Reference Alizadeh, Djafarian and Alizadeh80) .

We followed the standardised scoring system for the operationalization of the WCRF/AICR recommendations developed by a collaborative group including, among the others, researchers from the US National Cancer Institute and WCRF/AICR Continuous Update Project Expert Panel in order to improve comparability and consistency across studies(Reference Shams-White, Brockton and Mitrou50,Reference Shams-White, Romaguera and Mitrou51) . We were unable to include information on waist circumference in the body fatness recommendation because the self-reported waist circumference measure was not available for 147 cases and 314 controls; we adapted the recommendation on physical activity according to data availability; we used energy density as a proxy for the consumption of fast foods and other processed foods high in fat, starches or sugars, whose consumption was not specifically collected by the FFQ and we did not consider the optional recommendation on breastfeeding.

Selection bias should be limited in our study, as we excluded from the control group women admitted to hospitals for hormone-related or gynaecologic conditions or any disease leading to long-term modifications in diet. Moreover, a low refusal rate was observed and the recruitment areas were similar for cases and controls. With reference to information bias, it was limited through the direct interview of cases and controls by the same trained interviewers in similar hospital conditions. In addition, we analysed the impact of the adherence to the WCRF/AICR score proposed in 2018 on data collected between 1992 and 2006 in a population unaware of those recommendations. Weight and height were self-reported, and BMI tended, therefore, to be underestimated, but this is unlikely to be differential between cases and controls. Finally, among limitations, information on grade, stage and possible therapy of cancer cases was not available; however, these factors are unlikely to materially influence diet-related associations. The relatively large sample size, the satisfactory reproducibility(Reference Franceschi, Barbone and Negri46,Reference Franceschi, Negri and Salvini47) and validity(Reference Decarli, Franceschi and Ferraroni48) of the FFQ and the allowance for several potential confounding factors represented the strengths of the study.

In conclusion, in this study higher adherence to the WCRF/AICR recommendations was associated with about 60 % reduced risk of endometrial cancer; while body weight had the strongest influence on the risk, a score considering only recommendations related to diet decreased the risk as well. Maintaining a healthy weight throughout life is the key recommendation for the prevention of this neoplasm. Being physically active and follow a healthy diet may also contribute to endometrial cancer prevention.

Acknowledgements

Data collection was supported by Fondazione AIRC (Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro).

Conceptualisation: F. P., E. N., and C. L. V.; methodology: F. T.; formal analysis and data curation: G. E. and F. T.; investigation, D. S., A. C., E. N., and C. L. V.; writing – original draft: G. E.; writing–review and editing: C. L. V., F. P., and F. T.; all authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114522002872