Introduction

The number of students enrolling on Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) Secondary (aged 11–18) Music courses in England and Wales has fallen substantially in recent years (e.g. UK Government, 2019). This is part of wider decline, with regular media stories in recent years about unfilled training places (Adams, Reference ADAMS2019; Bloom, Reference BLOOM2017; Mason, Reference MASON2016; Richardson, Reference RICHARDSON2017). While some secondary PGCE subjects can see their numbers drop because graduates can enter a related, and perhaps highly paid, industry (e.g. design and technology, mathematics and science), it is less immediately obvious for a drop in music applications. There are factors complicating comparison between the constituent countries of the UK, such as differing GCSE requirements for entrants to secondary teacher training programmes between England and Wales – with England having slightly lower entry requirements (GCSE grade C in English language and mathematics, as opposed to grade B in Wales) – and higher financial incentives for students in England than Wales (Department for Education, 2017; Welsh Government, 2016). There is, however, limited evidence to date of the views of students about what influences their decision to apply for a secondary music PGCE programme. This article outlines an attempt to gather the thoughts and opinions of undergraduate music students at higher education institutions across England and Wales, with the aim of exploring why student applications have dropped for secondary music PGCE courses.

Context

There are many parties interested in exploring motivation to train as a teacher. Internationally, there is a large corpus of work by governments and related agencies, but this can be a pragmatic exercise to assess the impact of their policies and incentives (Low et al., Reference LOW, LIM, CH’NG and GOH2011). Kyriacou and Coulthard (Reference KYRIACOU and COULTHARD2000) and Moran et al. (Reference MORAN, KILPATRICK, ABBOTT, DALLAT and McCLUNE2001) both reflect a wide range of academic literature which proposes the division of persuading factors into the altruistic, the intrinsic and the extrinsic. Barmby (Reference BARMBY2006) further proposes a ‘children-orientated’ factor, which correlates closely with the altruistic and intrinsic factors, and a ‘flexibility’ factor which relates to the practicalities of the job.

All of these factors can serve as both positive and negative influences. Altruism, in the form of a desire to work with children, is a common positive factor in many international studies (e.g. Fokkens-Bruinsma & Canrinus, Reference FOKKENS-BRUINSMA and CANRINUS2014; Manuel & Hughes, Reference MANUEL and HUGHES2006; Taylor, Reference TAYLOR2006; Watt et al., Reference WATT, RICHARDSON, KLUSMANN, KUNTER, BEYER, TRAUTWEIN and BAUMERT2012). Jones and Parkes (Reference JONES and PARKES2010) conclude that ‘altruistic’ and ‘intrinsic’ factors rank highly in importance amongst the undergraduate students but, supporting older work by Jarvis and Woodrow (Reference JARVIS and WOODROW2005), they also point to the need for a stable career to be an important factor, which may affect music more given the lack of possible stable career paths. Sometimes, however, the positive factors are much more intrinsic and apparently simple, such as a study of Australian students by Manuel and Hughes (Reference MANUEL and HUGHES2006), where attaining personal fulfilment such as a ‘dream’ job, are significant. A small-scale Belgian study by Rots, Kelchtermans and Aelterman (Reference ROTS, KELCHTERMANS and AELTERMAN2012) suggested that even within groups of students who embark on a teacher training programme, there will still be a mix of altruistic, intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, including those who do not intend to teach – although they note that such attitudes can be changed during the programme. However, Rots et al. (Reference ROTS, AELTERMAN, DEVOS and VLERICK2010) conclude that most students enter teacher education with a motivation to become teachers. Overall, however, studies into the motivation of teachers generally conclude that the altruistic and intrinsic factors outweigh the extrinsic ones (Moran et al., Reference MORAN, KILPATRICK, ABBOTT, DALLAT and McCLUNE2001; Thornton, Bricheno & Reid, Reference THORNTON, BRICHENO and REID2002).

In contrast, other generic factors can negatively impact on a student’s decision to undertake teacher training, whatever the subject. For instance, Braun (Reference BRAUN2014) highlights external factors, such as a lack of esteem for the teaching profession as a whole, echoed by Hargreaves (Reference HARGREAVES2009), as well as the potential impact of class and gender. Additional negative factors include workload (Smithers & Robinson, Reference SMITHERS and ROBINSON2003) and financial issues (Barmby, Reference BARMBY2006).

Government policy in any country can act as both a barrier and an enabler, as incentives and entry requirements are introduced, amended or abolished. In the UK, the policy situation is further complicated with the advent of devolved powers in education to Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland, with England’s increasingly being seen as an ‘outlier’ (Beauchamp et al., Reference BEAUCHAMP, Clarke, Hulme and Murray2015). This does, however, present challenges given its large numerical dominance in terms of teacher training places and the close geographical proximity of many providers, particularly between Wales and England. This means, for instance, that if a student decides to train as a teacher in Wales, they may receive lower financial incentives for shortage subjects and good degree results (DfE, 2017; Welsh Government, 2016) and be subject to higher exceptions at GCSE. Although this can be advantageous for students, it does present challenges to meeting target numbers. Nevertheless, an international study by Watt et al. (Reference WATT, RICHARDSON, KLUSMANN, KUNTER, BEYER, TRAUTWEIN and BAUMERT2012) concluded that government policy is more likely to affect perceptions of teaching, rather than motivations for teaching.

Finally, the impact of the media cannot be ignored. In the UK, for instance, the media provide many reasons behind the lack of trainees entering the teaching profession including low pay (National Union of Teachers, 2016), government interference (New Statesman, 2016) and issues around the violent behaviour of students (Richardson, Reference RICHARDSON2016).

Identity: musician or teacher?

Nevertheless, besides generic perceptions of teaching, there may be other factors which impact (positively or negatively) on student motivation, such as the identity of teachers as scientist, mathematician, or, in this case, musician. A number of articles from the USA attempt to define the self-perceptions which lead undergraduates to identify as either a musician or a teacher before they have completed their undergraduate studies. In England, Garnett (Reference GARNETT2014) found similar issues, but suggests they could be avoided if pedagogy was an integral part of musicianship from the earliest stages. In this context, Jones and Parkes (Reference JONES and PARKES2010) define three ‘domains’ of identity: music educator, performer and general musician and state that a positive sense of identity as a music educator is the only predictor of choosing a career in music teaching, with no correlation with identity as a performer or with any self-perception of performing talent. They conclude the only way to increase the number of students opting for a career in music teaching is to increase their sense of identity as educators via their experience in university, due to the strong influence of the undergraduate years (Isbell, Reference ISBELL2008 p.176).

Meanwhile, Pellegrino (Reference PELLEGRINO2009) points to tension between the two identities of performer and teacher and summarises a discussion between Bernard (Reference BERNARD2005), Roberts (Reference ROBERTS2007), Bouij (Reference BOUIJ2007), Dolloff (Reference DOLLOFF2007) and Stephens (Reference STEPHENS2007) in which the issue of musician identity versus teacher identity is debated at length. In the UK, the idea of the music teacher as a musician in the classroom, and hence a symbiosis of the two supposedly conflicting identities, was proposed significantly earlier by Swanwick (Reference SWANWICK1988) and provides an effective counter-argument which is a more ‘altruistic’ (Stephens, Reference STEPHENS2007 p.8) solution to the problem (as well as making for more effective teachers of music) than Bernard (Reference BERNARD2005) proposes. In response to Bernard’s (Reference BERNARD2005) suggestion that it is necessary for music teachers to find some way of reconciling the two warring identities within them, Stephens prefers to recognise ‘the importance of a creative, artistic or musical identity in effective teaching’ (Reference STEPHENS2007, p.17).

One of the few more recent UK-based studies into the reasons for choosing to train as a teacher, by Jarvis and Woodrow (Reference JARVIS and WOODROW2005), does not examine the issue of ‘identity’ when categorising the findings from its survey of students, possibly because it is not a music-specific study, and perhaps this identity issue is not such a major factor for teachers of some other subjects. The closest definition is ‘always wanted to teach’. Furthermore, results for music students (the study surveyed 12 PGCE subjects) were surprising in a number of ways, with music students reporting a very low response to ‘vocational’ reasons for wishing to teach music, and a zero response for wishing to continue their involvement with their subject. These surprising results, possibly related to the low number of music trainees surveyed, as well as the significant changes in the education landscape in the UK since 2005, make a strong case for a need to investigate these issues again, with a focus on the subject of music.

The aim of this study is to explore factors which impact on undergraduate music students’ attitudes towards teaching as a career, and the following research questions were developed:

-

1. What enabling factors attract undergraduate music students towards a career in secondary music teaching?

-

2. What demotivating factors, or barriers, do undergraduate music students perceive in choosing a career in secondary music teaching?

-

3. What is the impact, if any, of gender on differences in barriers and enablers which attract undergraduate music students towards a career in secondary music teaching?

Research design

In choosing a research instrument to gather data from students in a range of institutions around the UK, three core characteristics of the target population (students who may choose to undertake a music postgraduate teacher training programme) were considered: the large number of potential respondents; their geographic distribution; and the ethical and practical difficulty in gaining access to the contact details of individual students. The paper questionnaire is a useful starting point as it allows a large number of respondents to be approached without the researcher being physically present, and the data, if correctly formatted, can be analysed relatively quickly and easily (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, Reference COHEN, Manion and Morrison2013, p.377). However, a traditional paper-based survey would be both impractical and unwieldy. In this context, an online survey, which is becoming an essential research tool (Vehovar & Manfreda, Reference VEHOVAR, MANFREDA, Fielding, Lee and Blank2016), was selected.

Online surveys have many benefits over other survey methods, including the potential of high response rates (Glover & Bush, Reference GLOVER and BUSH2005), being easier to administer and less work than paper-based surveys (Harlow, Reference HARLOW2010). There are also limitations, however, including the potential for self-selection bias (those who reply, e.g., have an interest in teaching music as a career) (Wright, Reference WRIGHT2005) and the potential non-representative nature of the internet population as a whole (Eysenbach & Wyatt, Reference EYSENBACH and WYATT2002). The latter could, however, be avoided by the use of appropriate focused networks, such as university music departments. Overall, the potential advantages of an online survey outweighed any disadvantages, so an online survey was constructed for distribution through appropriate networks.

The questions asked were divided into four categories:

-

1. Simple multiple-choice questions relating to the identities of the students: age and gender (both optional), type of degree, HE institution, year of study.

-

2. More complex multiple-choice questions (based on the literature review) gave the opportunity to identify factors currently persuading them, factors currently dissuading them and hypothetical factors which, if present, might increase the likelihood of them choosing to enrol on a PGCE secondary music course.

-

3. Multiple-choice questions in which students outlined their educational and musical background. This was intended to provide an insight into any possible effect of the recent fracturing of the English school system into many different types of schools, and also to try and glean some information about whether a broad range of types of musicians are currently studying in what have traditionally been ‘feeder’ courses into PGCE music programmes.

-

4. A Likert scale attitudinal question (six-point, 0–5 scale) in which students expressed the likelihood of them applying for a PGCE secondary music programme at any point in the future, followed by an opportunity to predict how long between completing their degree and enrolling on the PGCE they would envisage waiting.

The survey was intended to gauge the perceptions of a large number of students of the likelihood of them applying for a PGCE secondary music course at some point after graduating. Linked to this fundamental area of enquiry was an opportunity for students to pick the factors (enablers) that attracted them towards a career in secondary music teaching and, conversely, to identify factors which put them off (barriers). Further questions in the survey were intended to ‘paint a picture’ of the students’ musical backgrounds, as well as their own educational experience, reflecting the diverse range of types of school which now exist in England in particular, to allow for possible correlation between factors.

The questions were drawn from empirical evidence of potential factors affecting reasons for choosing to undertake a music teacher training programme. The process of constructing the survey items aligned with the following research base:

-

Categorisations of motivators and demotivators outlined in Jarvis and Woodrow (Reference JARVIS and WOODROW2005), Barmby (Reference BARMBY2006) and Jones and Parkes (Reference JONES and PARKES2010).

-

The inclusion of identity issues, as explored by Isbell (Reference ISBELL2008) and others.

-

The inclusion of recent changes in the requirements for entry to Initial Teacher Education courses in Wales in relation to literacy and numeracy (Welsh Government, 2012).

After gaining ethical consent under the university ethics protocol, the questionnaire link was emailed to programme directors in 35 HE providers across the UK, who were asked to forward the contents to their UG students. The mailing list was based on information gathered from undergraduate music programmes on UCAS and available contact details on university or conservatoire web sites. No software was required to complete the survey, only an internet connection, and the survey could be completed on both mobile devices (including phones) and fixed PCs. Informed ethical consent was built into the completion of the survey.

Sample

In total, 46 students completed the compulsory questions in the survey and these students represented eight institutions in England and Wales: seven universities and one conservatoire. One additional conservatoire response was only partially completed and is not included in the results below. Just over half (54%) of the responses were from students at one university, near to where this study was undertaken as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Institutions in sample

In this purposive random sample, the majority (76%) of respondents were female, compared to 44% of female students who study music at UG level (HESA, 2020). Such responses are not unusual in online survey as respondents self-select whether to participate (Bethlehem, Reference BETHLEHEM2010). This does skew the sample in favour of female responses, but there are sufficient male responses to enable a valid comparison to be made. In addition, just over half of responses were received from the nearest university UG music provider. As no attempt was being made to compare providers, all individual responses were considered equally, as, most importantly, all respondents were able to offer ‘richly-textured information’ (Vasileiou et al., Reference VASILEIOU, BARNETT, THORPE and YOUNG2018, p.2), relevant to the main aim of the study to explore undergraduate music students’ attitudes towards teaching as a career. The great majority of students (over 87%) were studying music as a single subject, as opposed to a joint honours degree or some other subject including music.

Results

Musical background

When asked for their principal, second and third studies (if applicable), almost every study reported by students was an ‘orchestral’ or brass band instrument, voice or occasionally the saxophone, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. What type of musical ensemble do you participate in on a regular basis? Please select all that apply. Ranked by popularity

This table shows the dominance of musical experiences that belong to the ‘Western classical’ tradition, potentially reflecting a body of literature suggesting a mismatch between the ‘habitus’ of music teachers and the musical interests and identities of the pupils in schools (e.g. Dwyer, Reference DWYER2019; Wright, Reference WRIGHT2008).

The results will now be considered in two broad categorisations before summarising the data in a conceptual model. These categorisations are intended to represent attitudinal perceptions of enabling, or motivating factors (enablers) or demotivating factors (barriers). The results will hence be structured around the first two research questions, with the third (gender) being interwoven into each section.

What enabling factors attract undergraduate music students towards a career in secondary music teaching?

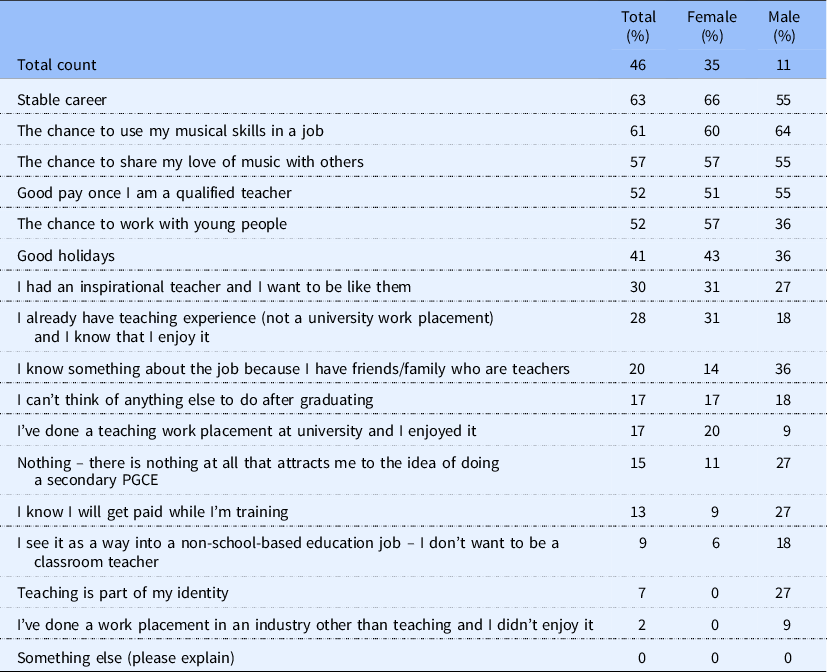

To assess current factors which would motivate students, they were asked: ‘What factors attract you to the idea of doing a PGCE secondary music course?’ Choices reflected the literature discussed above, and in this question respondents were allowed multiple responses so as to gain a full picture. Responses in this and subsequent tables are shown in total, but also shown by gender. The total responses are divided into three categories: significant if responses are above 60%, moderate if 50%–59% and low if 40%–49%.

Responses in Table 3 show a mixture of altruistic and pragmatic factors is largely common for both genders. The only factors considered significant are pragmatic issues: a stable career (although more important for female respondents) and a chance to use musical skills. Moderate factors include not only pragmatic issues of good pay but also more altruistic factors of sharing a love of music and a chance to work with young people. There is, however, a significant gender divide on the latter with 57% of female and only 36% of male respondents. The only factor classified as low is good holidays.

Table 3. What factors attract you to the idea of doing a PGCE secondary music course? Tick all that apply. Ranked by overall popularity and broken down by gender

When asked what additional factors would motivate them to do a PGCE, data in Table 4 again show that pragmatic concerns emerged as significant, with ‘a training wage or grant while doing a PGCE’ clearly the most important motivator (65%). There is, however, a clear gender divide in this, with 71% of females, compared to 45% of males. Money was again the next most important motivator with ‘a better starting salary’ emerging as a motivator for 52% of respondents, with no significant gender difference. Although most responses contained no significant gender differences, it is worth considering those that differ. For instance, 54% of female respondents identified ‘Being able to combine teaching with being a professional musician’ as a motivator, compared to only 27% of the males. In addition, and perhaps correlated, 27% of the male respondents suggested: ‘Nothing – I’m definitely not going to do a PGCE secondary music course and I can’t be persuaded!’, compared to only 9% of females. Another significant difference was the fact 14% of the females were motivated by ‘More support with numeracy’, compared to 0% of the males.

Table 4. Which of these would make you more likely to do a PGCE secondary music course? Please tick all that apply

What demotivating factors, or barriers, do undergraduate music students perceive in choosing a career in secondary music teaching?

It is important to also consider demotivating factors and consider how they may influence decisions to undertake a PGCE, summarised in Table 5. Interestingly, no factor identified in the literature was rated as significant. Nevertheless, some of the key areas presented in press coverage of schools, such as ‘poor behaviour’ (59%, with more males than females) and ‘workload’’ (50%, again more males than females) as the only factors identified by over 50% of the respondents. Perhaps slightly contradictory to the 54% of females who identified ‘Being able to combine teaching with being a professional musician’ as a motivator, 40% of females considered they would have ‘failed as a performer/composer if I become a classroom teacher’. There is also a key gender difference here, with only 18% of males noting this. Another key gender difference in barriers, although inversely perhaps a positive for the teaching profession as a whole, is that 40% of females wanted to ‘be a classroom teacher, but not a secondary teacher (perhaps primary, further education or higher education)’ – compared to only 9% of males. Another key difference was that 20% females felt they were ‘bad at speaking to a large group’ compared to only 9% of males.

Table 5. What factors put you off the idea of doing a PGCE secondary music course (even if you think you might do the course)? Please tick all that apply. Ranked by overall popularity and broken down by gender

Both genders (33% overall) identified that ‘I want to have a shot at a professional career in performing/composing’ – with slightly more males (36%), compared to females (31%) – perhaps indicating a key dilemma for those who have spent many years honing their relevant musical skills.

Of the students who gave ‘other’ reasons, there was no obvious pattern as shown below:

-

I wouldn’t want to be limited to just teaching music.

-

The unstability (sic) in the profession at the moment.

-

Young people not taking music seriously would really upset me.

-

Don’t want to teach students who don’t want to learn.

-

it’s a career suffering huge government cuts and no support from anyone.

-

I’m too old!

-

I am worried about the workload of a qualified music teacher and lack of funding/support.

Discussion

In discussing the findings, we are mindful of the difficulty in understanding the detailed motivations of respondents due to the nature of the survey responses, and the dominance of female respondents. Indeed, we suggest below that a more detailed exploration through in-depth interviews would help to add further nuance to the findings. Despite these notes of caution, however, the data reveal interesting, and potentially useful, areas for discussion.

We propose that, while altruistic motivations and practical job-related features (pay, holidays, stable career) are strongly attractive to both genders, overall, they are both slightly more attractive to females, than males, in this sample. We also suggest that, in this sample at least, the male respondents appear to have come to a clearer conclusion that teaching is for them or not, as not only were males more likely to report teaching as being part of their identity, they were also more likely to report that nothing attracted them to teaching, or that they had already decided they would make a bad teacher.

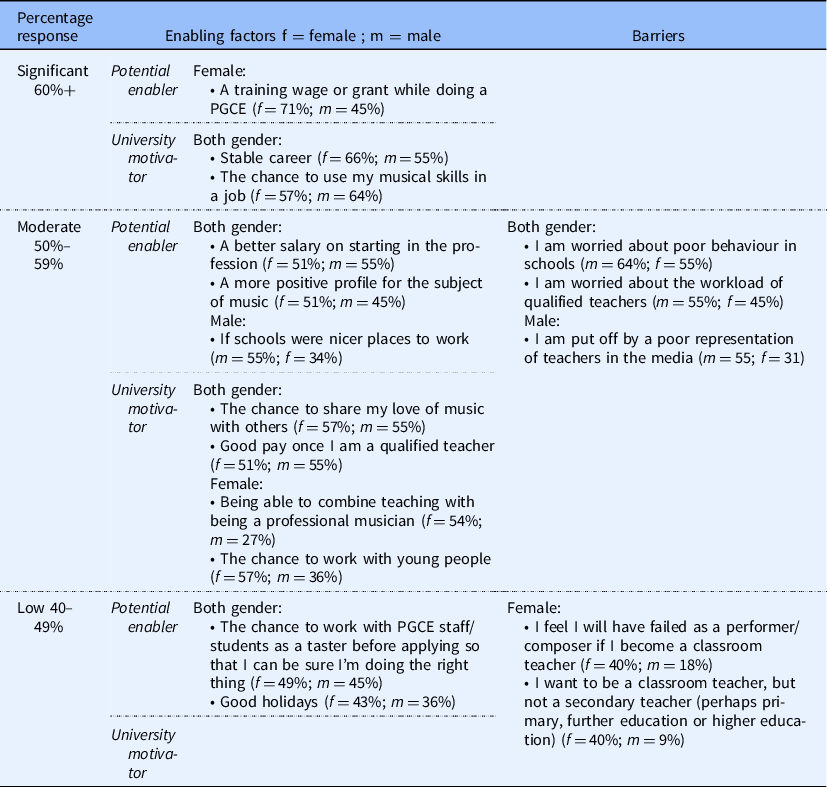

Table 6 provides a summary of the perceived potential enabling factors and barriers to secondary music PGCE, and hence secondary music teaching, for undergraduate musicians. Most items are reported as applying to both genders. However, a more nuanced analysis shows that some apply more to a single gender. If there was a gap of more than 20% between the genders, these items are reported as applying more to one gender only. As in other tables, responses are considered: significant if responses are above 60%, moderate if 50%–59% and low if 40%–49%. No responses below 39% are considered in this table, but can be found in Tables 3–5. The table also importantly splits each level of response into ‘potential enabler’, those outside the control of universities and ‘university motivator’, potentially within their control to promote.

Table 6. Summary of enabling factors and barriers to secondary music PGCE for undergraduate musicians

Conclusions

This study suggests that undergraduate music students do not perceive any significant (more than 60%) barriers to undertaking a PGCE in secondary music. In addition, while the perennial issues of teacher workload and pupil behaviour are not within the control of university music departments, this study suggests that there are generic areas which can be promoted by universities which may appeal to potential applicants. Furthermore, there are also distinctive issues that could be addressed with male and female students to inform and encourage them to consider a PGCE programme as the next steps in their career.

Having said this, this research is just the first step in probing these issues in more detail in future in-depth qualitative research. This is situated in a downward trend in numbers applying to study a PGCE in Secondary Music, despite this research suggesting that there are more enablers than barriers to encourage undergraduate music students to undertake a PGCE. For instance, the data suggest that there are differences in perceptions based on gender, which would benefit from in-depth analysis.

Overall, we conclude, optimistically, that this study suggests that there are more enablers than barriers to encourage undergraduate music students to undertake a PGCE.