Article contents

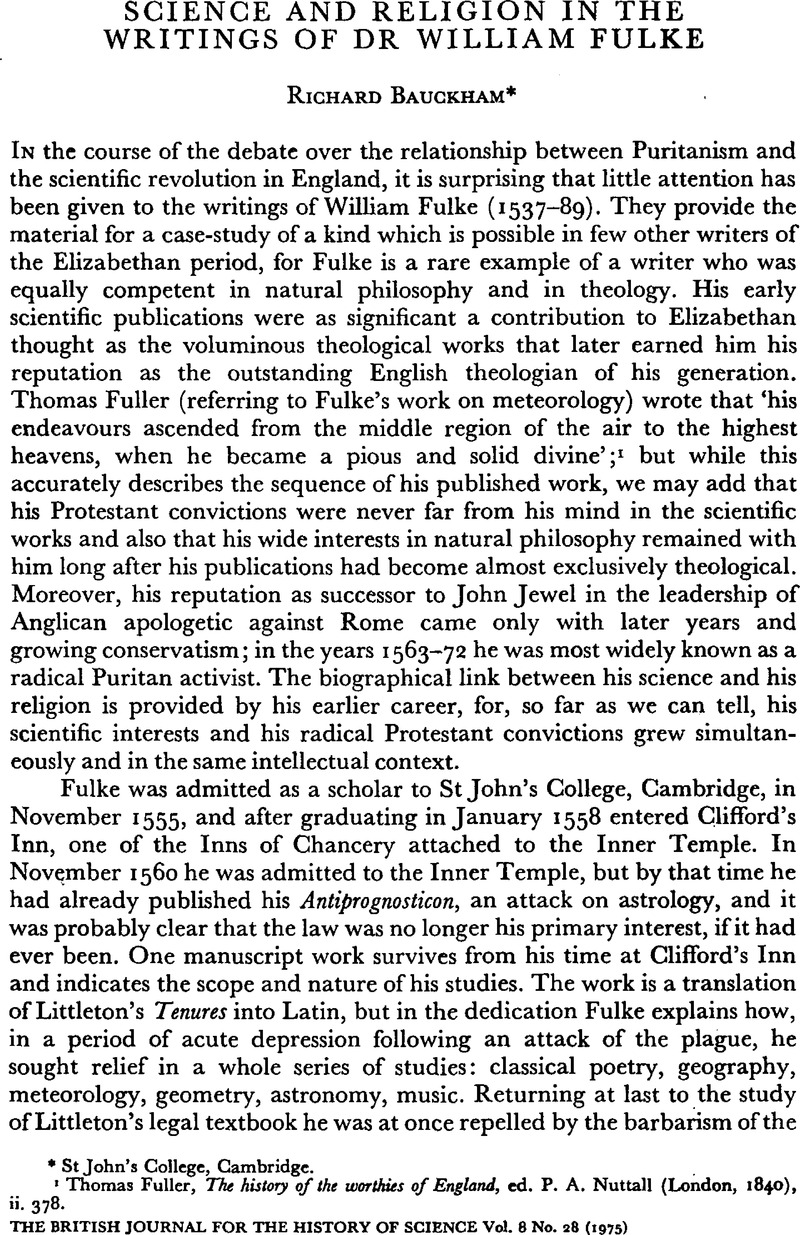

Science and Religion in the Writings of Dr William Fulke

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 January 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Presidential Address

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © British Society for the History of Science 1975

References

1 Fuller, Thomas, The hiitory of the worthies of England, ed. Nuttall, P. A. (London, 1840), ii. 378.Google Scholar

2 Bodleian Library, MS. Rawlinson C. 673, dedication (unpaginated).

3 See Starkey, Thomas, A dialogue between Reginald Pole and Thomas Lupset, ed. Burton, K. M. (London, 1948), p. 174Google Scholar; Elton, G. R., ‘Reform by statute’ (Raleigh lecture, 1968), Proceedings of the British Academy, liv (1968), 177, 179.Google Scholar

4 Further biographical detail will be found in Bauckham, R., ‘The career and thought of Dr William Fulke (1537–1589)’ (Cambridge University Ph.D. thesis, 1973).Google Scholar

5 Remaining Fellows included Bartholomew Dodington (later Regius Professer of Greek) and Miles Buckley (whose inventory, 1559, included an impressive list of Hebrew books).

6 See French, P. J., John Dee: the world of an Elizabethan magus (London, 1972), pp. 23–4Google Scholar; Hudson, W. S., John Ponet (1516?–1556): advocate of limited monarchy (Chicago, 1942), pp. 12–13.Google Scholar

7 Fletcher, R. J., ‘The Reformation and the Inns of Court’, Transactions of the St Paul's Ecclesiological Society, v (1905), 154.Google Scholar

8 Fulke, W., Antiprognosticon that is to saye, an invective agaynst the vayne and unprofitable predictions of the astrologians, trans. Painter, W. (London, 1560)Google Scholar, sigs.Biiiir, Bviiv, Bviiiv, Cviv. In this article William Painter's English translation of Fulke's Antiprognosticon will be cited as Antiprognosticon; Fulke's original Latin version as Antiprognosticon contra praedictiones.

9 References to John Lucas junior at the Inner Temple in 1560 and 1563 are in Inderwick, F. A., A calendar ofthe Inner Temple records (London, 1896), i. 160, 213.Google Scholar The index wrongly confuses him with John Lucas senior.

10 It has been stated (DNB article on Painter, followed by Dick, H. G., ‘The authorship of Four Great Lyers (1585)’, The library, 4th ser. xix [1939], 311–14)Google Scholar that Painter added material of his own to the translation; this is incorrect. The appended ‘short treatise’ is an additional, more popular work by Fulke himself.

11 Bennet, H., A famous and godly history (London, 1561).Google Scholar

12 See note 40, below.

13 Fulke, W. and Lever, R., The most noble auncient, and learned playe, called the philosophers game (London, 1563)Google Scholar. On the joint authorship and their subsequent dispute, see Rosenberg, E., Leicester, patron of letters (New York, 1955), pp. 40 ff.Google Scholar

14 Murray, H. J. R., A history of board-games other than chess (Oxford, 1952), p. 84.Google Scholar

15 OYPANOMAXIA, hoc est, astrologorum ludus (London, 1571)Google Scholar; some copies are dated 1572. METPOMAXIA sive ludus geometricus (London, 1578).Google Scholar

16 Μετρομαχία, sigs. Aiiir–Aiiiir.

17 Euclid, , The elements of geometrie, trans. Billingsley, H. (London, 1571)Google Scholar, sigs. Aiiiir, biiv–biiir.

18 A goodly gallerye with a most pleasaunt prospect, into the garden of naturall contemplation, to behold the naturall causes of all kynde of meteors. This was the title of the first edition (London, 1563). My references are all to the 1602 edition, which was entitled A most pleasant prospect (etc.). Bibliographical details of editions up to 1670 will be found in Bauckham, , op. cit. (4), p. 414.Google Scholar

19 E.g. Seneca on comets: ‘when God, the greatest part of the universe, is an unknown God, we are surprised, are we, that there are some specks of fire we do not understand?’, in Quaestiones naturales, VII. xxxi; trans. Clarke, J. (London, 1910), p. 305.Google Scholar

20 ‘The scientists… postulate causes for lightning, winds, eclipses, and other inexplicable things never hesitating for a moment, as if they had exclusive knowledge about the secrets of nature’, in The praise of folly, in Dolan, J. P. (ed.), The essential Erasmus (New York, 1964), p. 142.Google Scholar

21 E.g. Jewel, John, Works (Cambridge: Parker Society edition, 1845–1850), iv. 1183.Google Scholar Cf. Kocher, Paul, Science and religion in Elizabethan England (San Marino, California, 1953), pp. 72 ff.Google Scholar

22 Harleian MS. 422, fol. 166v; Nowell, A. and Daye, W., A true report of the disputation had in the Tower (London, 1584), sig. Nivr.Google Scholar

23 Allen, D. C., The star-crossed Renaissance (New York, 1941), chapter 1, and pp. 101–2Google Scholar; Dick, H. G., in Tomkis, Thomas, Albumazar, ed. Dick, H. G. (Berkeley, 1944), pp. 21–2.Google Scholar

24 Thomas, K., Religion and the decline of magic. Studies in popular beliefs in sixteenth and seventeenth century England (London, 1971), pp. 291–2, 324–32Google Scholar; Kocher, , op. cit. (21), pp. 202–3.Google Scholar

25 Thomas, , op. cit. (24), p. 288.Google Scholar

26 Antiprognosticon, sig. Aiiiir.

27 Ibid., sig. Diir. A strong attack on Fulke's work appeared in Latin verses by Edward Dering prefaced to Palingenius, M., The firste syxe bokes of the zodiake of life, trans. Googe, B. (London, 1561).Google Scholar

28 Antiprognosticon, sig. Aiiiiv.

29 Dacquet, P., Almanack novum et perpetuum (London, 1556).Google Scholar

30 Antiprognosticon, sig. Div.

31 For Coverdale, see Thomas, , op. cit. (24), p. 367 n.Google Scholar See also Hutchinson, Roger, The image of God(1550), in Works (Cambridge: Parker Society edition, 1842), pp. 77–8Google Scholar; Hooper, John, A declaration of the ten holy commandementes (1548?), in Writings (Cambridge: Parker Society edition, 1843), i. 308–9, 328–33.Google Scholar

32 According to Allen, , op. cit. (23), p. 111Google Scholar, Fulke's work contains ‘no arguments that cannot be read in some continental polemic’.

33 Coxe, F., A short treatise declaringe the detestable wickednesse of magicall sciences (London, 1561), sigs. Aivv–Avr.Google Scholar

34 Antiprognosticon, sig. Bir.

35 Ibid., sig. Cviv. The work was probably an appendix or preface to a prognostication. Cuningham was distinguished by Fulke as ‘vir alioqui doctus et probus, sed huius artis non vulgaris professor’ (Antiprognosticon contra praedictiones, sig. B4r).

36 Larkey, S. V., ‘Astrology and politics in the first years of Elizabeth's reign’, Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine, iii (1935), 171–86.Google Scholar

37 Allen, , op. cit. (23), pp. 108–12.Google Scholar

38 Antiprognosticon, sigs. Aiiiiv, Diiiir, Dviiv. Among the standard works to which Fulke referred were Joannes Sacro Bosco, Spherae tractatus; Bernard Sylvestris, De mundi universitate; John Indagine (Jean de Hayn), Introductions apotelesmaticae.

39 Antiprognosticon, sigs. Aiiiiv–Avr.

40 Entered in the Stationers' Register for 1560–1 and 1562–3. See Arber, E. (ed.), A transcript of the registers of the Company of Stationers (London, 1875), i. 153, 205Google Scholar; cf. Bosanquet, E., English printed almanacks (London, 1917), pp. 194–5.Google ScholarLarkey, , op. cit. (36), p. 174Google Scholar, regarded these entries as references to the Antiprognosticon (for which otherwise no entry occurs); but on this suggestion it is difficult to explain the second entry, which has a different publisher. No second edition of the Antiprognosticon is known.

41 For example, Francis Coxe's Prognostication for 1566 confines its astrological material to weather-forecasting and medical advice: these, though repudiated by Fulke, were widely accepted by theologians as legitimate uses of astrology, and so this work of Coxe's ought not to be seen as so complete a reversal of his attack on astrology in A short treatise as has been supposed: see DNB article on Coxe, and Bosanquet, , op. cit. (40), p. 39.Google Scholar For a summary of the contents of the average Elizabethan almanac, see Kocher, , op. cit. (21), pp. 208–9.Google Scholar

42 Chamber, John, A treatise against judicial astrologie (London, 1601), p. 2.Google Scholar

43 Trinity College, Dublin, MS. 235.

44 Ούρανομαχία sig. Aivv.

45 Ibid., sig. Bir.

46 Trinity College, Dublin, MS. 165, fol. 230r-v. This manuscript is a seventeenth-century edition of a sixteenth-century work which in all probability is by Fulke; for the date of the original 1570–9 and the complex problem of authorship, see the discussion in Bauckham, op. cit. (4), bibliographical note 2.

47 Trinity College, Dublin, MS. 165, fol. 148v.

48 Harvey, R., An astrological discourse (London, 1583), sig.¶ iiiir.Google Scholar

49 Allen's opinion was that Fulke's ‘seeming incongruity of attitude and performance is … removed by noticing that Fulke, like many of the opponents of astrology, was against only the judicial phases of the science’; see Allen, , op. cit. (23), p. 106.Google Scholar But this explanation fails to take account of the full force of the argument in the Antiprognosticon, and moreover Allen ignored the Ούρανομαχία and did not know of Trinity College, Dublin, MS. 165. The astrological signs and properties which feature prominently in the Ούρανομαχίαare ridiculed as entirely spurious in the Antiprognosticon.

50 The reference to Trismegistus is in one of the Catholic manuscript accounts (Harleian MS. 422, fol. 166v) but omitted in the Protestant account of the dispute which John Field prepared and Fulke approved; see Nowell, and Daye, , loc. cit. (22).Google Scholar

51 Antiprognosticon, sig. Aviv: ‘the difference of these artes, I thynke is manifestly knowen to all men’.

52 Calvin spoke of astronomy as true astrology. Coxe, , op. cit. (33)Google Scholar, sig. Aviv, opposed ‘the simple knowledge of Astrologie’ to ‘the curious parts of Astrologie’. Hooper, , op. cit. (31), i. 331Google Scholar, used ‘astrologer’ and ‘astronomer’ in precisely the opposite senses to those in Fulke's (and the normal) usage.

53 Antiprognosticon, sig. Biv. Cf. Calvin, , An admonition against astrology, trans. Gylby, G. (London, 1561), sig. Dir.Google Scholar

54 Aristotle, , Meteorologica, I. iiGoogle Scholar; quoted in Antiprognosticon, sig. Bviiiv.

55 This is not too different from Pico's attitude, as described in Walker, D. P., Spiritual and demonic magic from Ficino to Campanella (London, 1958), p. 56Google Scholar: ‘Pico insists that celestial influences are only a universal cause of sublunar phenomena; all specifie differences of quality or motion are due to differences inherent in the receiving matter or soul’. Celestial influences could therefore neither be controlled for specific effects, as in the magical tradition, nor predicted, as in the kind of astrology which Fulke is more directly attacking.

56 Antiprognosticon contra praedictiones, sig. A6r: ‘pulcherrima, et certissimam Astronomiae scientiam’.

57 Antiprognosticon, sig. Avv.

58 Ibid., sigs. Avv, Bviiir.

59 Ibid., sig. Cviir.

60 Ibid., sig. Dviir-v.

61 See Calvin, , op. cit. (53)Google Scholar, sigs. Aviir–Aviiiv, Civ–Ciiv, Dir; Hooper, , op. cit. (31), i. 332Google Scholar; Hutchinson, , op. cit. (31), p. 78Google Scholar; and (for William Perkins) Kocher, , op. cit. (21), p. 216.Google Scholar

62 The theological arguments are well summarized in Kocher, , op. cit. (21), p. 215.Google Scholar Cf. Walker, , op. cit. (55), p. 55.Google Scholar

63 Pilkington, James, Works (Cambridge: Parker Society edition, 1842), p. 17.Google Scholar

64 Calvin, , op. cit. (53), sig. Biiiiv.Google Scholar

65 Hutchinson, , op. cit. (31), p. 78.Google Scholar

66 Antiprognosticon contra praedictiones, sig. D4r. On the popularity of the adage, see Wedel, T. O., The mediaeval attitude toward astrology (Yale Studies in English. vol. lx, reprinted 1968), PP. 68, 135, 137–8.Google Scholar

67 Antiprognosticon, sig. Ciiir. Both these quotations were used by astrologers themselves. but in practice they treated their predictions as very probable and thought most men unlikely to be able to resist the influence of the stars.

68 Antiprognosticon, sig. Ciir.

69 Hooper, , op. cit. (31), i. 331–3, 308Google Scholar; Calvin, , op. cit. (53), sigs. Ciir–CviirGoogle Scholar; Kocher, , op. cit. (21), pp. 217–21.Google Scholar

70 Antiprognosticon, sig. Diiiv.

71 Ibid., sig. Dvv.

72 On sig. Cvir he took over from Chrysostom the argument that miraculous signs ir. the heavens attended the birth of Christ.

73 Kocher, , op. cit. (21), chapter 5, and pp. 215–24.Google Scholar

74 Antiprognosticon, sig. Dir-v.

75 ‘For gevynge to every cause her propre effecte, yet wyll I not graunt effecte to that whiche is no cause: or if it be a cause, I will not graunt that to be the effect which they wyll have’; ibid., sig. Cir.

76 Ibid., sig. Bvir.

77 Ibid., sig. Biir.

78 Ibid., sigs. Cir, Ciiiv–Cvir, Diiiir–Dvr, Cviiir. A parallel with Fulke's methods of theological argument may be drawn, in that in both cases he argues against uncritical acceptance of traditional knowledge—here the astrological System, there the tradition of the Roman church. The methods of testing such claims to knowledge differ, however, in the two contexts: astrology is open to testing by observation, theological traditions by their agreement with Scripture.

79 Ibid., sig. Dviiiv. He did admit the devilish nature of ancient prognosticators (sig. Bir).

80 Ibid., sig. Ciiiir.

81 Thomas, , op. cit. (24), p. 359.Google Scholar

82 Ibid., p. 368.

83 Fulke, , T. Stapleton and Martiall confuted (London, 1580), p. 75.Google Scholar

84 Fulke, , An apologie ofthe professors of the gospel in Fraunce (Cambridge, 1586), p. 23.Google Scholar

85 For this dichotomy as a problem for Elizabethan theologians, see Kocher, , op. cit. (21)Google Scholar, chapter 5. A less theoretical discussion of the question of providence is in Thomas, , op. cit. (24), chapter 4.Google Scholar

86 Antiprognosticon, sigs. Dvir–Dviir.

87 E.g. Hooper, , op. cit. (31), i. 331, 333, 308.Google Scholar Cf. Thomas, , op. cit. (24), p. 358Google Scholar; Kocher, , op. cit. (21), pp. 161–2.Google Scholar

88 Heninger, S. K., A handbook of Renaissance meteorology (Durham, N. Carolina, 1960).Google Scholar

89 Hill, Thomas, A contemplation of mystcries (London, 1571)Google Scholar, the only other extcnded discussion, was both heavily dependent on Fulke and reverted to much of the superstition and marvel-mongering which Fulke endeavoured to dissipate.

90 Trinity College, Dublin, MS. 165, fol. 117r.

91 For example, on whirlwinds (A goodly gallerye, fols. 32v–33v; cf. Aristotle, Meteorologica, III. i. 3700–371a) and on shooting stars (A goodly gallerye, fols. 7v–8v; cf. Aristotle, , Meteorologica, I. iv. 341b)Google Scholar he differed considerably from Aristotle; on lightning, while his basic theory was Aristotle's, he allowed for reflexion as Aristotle did not (A goodly gallerye, fols. 26v–27v; cf. Aristotle, , Meteorologica, II. ix. 370a)Google Scholar; he rejected Aristotle's theory of the Milky Way in favour of one taken from Plutarch (A goodly gallerye, fols. 38r–40r; cf. Aristotle, Meteorologica, I. viii, and Heninger, , op. cit. [88], p. 102).Google Scholar

92 He drew copiously on the three standard Works of antiquity: Aristotle, Meteorologica; Pliny, Historia naturalis; Seneca, Quaestiones naturales; though he avoided Pliny's addiction to the marvellous and was wary of Seneca's philosophy. He also drew on the opinion of other writers preserved in Plutarch (De placitis philosophorum), and on Theophrastus, Aratus of Soli, Ptolemy (Liber quadripartiti), Virgil, and (without acknowledgement, but see Heninger, , op. cit. [88], pp. 102–3)Google Scholar Macrobius (In somnium Scipionis). Of mediaeval writers, he used Isidore of Seville, Avicenna, and Albertus Magnus; and, of Renaissance writers, Girolamo Cardano (De rerum varietate) and (without acknowledgement) Giovanni Pontano (Meteororum liber). A full bibliography of printed works on meteorology available by 1558 is given in Heninger, , op. cit. (88).Google Scholar

93 A goodly gallerye, fols. 38r–40r.

94 Trinity College, Dublin, MS. 165, fol. 145v.

95 A goodly gallerye, fols. 29r–31r, 51v–53r, 15v–16r.

96 Heninger, S. K., ‘Tudor literature of the physical sciences’, Huntingdon Library quarterly, xxxii (1968–1969), 251, 252.Google Scholar

97 A goodly gallerye, fols. 10v, 9r-v, 25r.

98 Ibid., fols. 2v (that watery vapours are drawn up by the sun may be proved by observing the evaporation of water from a stone), 8v (the huge size of stars is shown to be credible by the example of the apparent size of a fire seen afar off), 49t (that rain in large drops falls from clouds close to the earth may be demonstrated by ‘a playne experiment’ of pouring water from different heights).

99 Ibid., fols. 70v–71r, 69v.

100 State Papers 12/38/11. II.

101 Kocher, , op. cit. (21), pp. 164–5.Google Scholar

102 A goodly gallerye, fols. 44r–45r.

103 Ibid., fols. 44v, 46r-v, 3v 5r.

104 For example, ibid., fol. 19r-v, on winds.

105 Ibid., fol. 11r.

106 Ibid., fols. 53v, 51v.

107 Ibid., fol. 44r.

108 Ibid., fols. 23v, 11v.

109 Kocher, , op. cit. (21), p. 162.Google Scholar

110 A goodly gallerye, fol. 26v.

111 In orthodox thought Satan could work (natural) wonders, but not (supernatural) miracles; see Kocher, , op. cit. (21), pp. 121–2, 124.Google Scholar

112 A goodly gallerye, fol. 12r.

113 Kocher, , op. cit. (21), p. 162.Google Scholar

- 3

- Cited by