Around four o’clock in the afternoon on Sunday 26 October 1623, Londoners were startled by the sound of a garret at the French ambassador’s residence collapsing, and the ensuing cries of the injured who were trapped amongst the fallen debris and rubble. This tragic accident, which sent shockwaves across the capital, killed almost 100 of the around 300 men, women and children of various social classes who were gathered at Blackfriars to hear a Catholic sermon by the acclaimed Jesuit preacher, Robert Drury. Not only did this illegal congregation include many Catholics who had confessed and received the sacraments prior to the sermon, but it also attracted ‘lukewarm’ Protestants and even a ‘wavering’ minister of the Church of England.Footnote 1 Occurring shortly after the failure of the unpopular Spanish Match negotiations, when anti-Spanish sentiment was at fever pitch, the tragedy unleashed a religious riot at the scene of the accident and a barrage of hostile anti-Catholic polemic in the weeks and months that followed.

In an insightful article, Alexandra Walsham demonstrated how the violence and invective unleashed by this tragedy were underpinned by shared and flexible ideas of providentialism about God’s interference in the world.Footnote 2 Walsham argued that Protestants not only interpreted this tragic event as divine judgement on Catholics, but also that the many responses to it show how providentialism was fused ‘with anti-popery to form a potent if volatile compound’.Footnote 3 Drawing on Peter Lake’s thesis that, in times of crisis, godly Protestants mobilised ‘large bodies of opinion’ by fusing anti-popery with popular anti-Catholicism to exacerbate divisions between church and state, Walsham suggested that ‘providentialism might be seen in a similar light’.Footnote 4 She therefore concluded that the terrible religious riot and polemic can be read as an implicit criticism and protest about James I’s pursuit of alliance with Spain and relaxation of the penal laws which accompanied the negotiations.

While Walsham’s essay provides valuable insight on providentialism and anti-popery, this article aims to read many of the same sources between the lines and against the grain, with a different aim. It will explore what they can tell us about tolerance of Catholics and embassy chapels in late Jacobean London. It demonstrates that the polemicists not only interpreted the Blackfriars disaster as a divine warning for Catholics, but also for the Protestants who tolerated them, which implicitly included the king. Although God’s judgment on everyday coexistence ultimately served as another tool to critique James’s pro-Spanish policies, the behaviours the polemicists attack shine much important light on religious tolerance and Catholicism in the English capital. Similarly, it is the authors’ anxieties about the popularity and visibility of communal devotions in embassy chapels which reveal the complex dynamics that allowed these spaces to simultaneously function as points of protection for Catholics, and sites of tension for Protestants.

Intriguingly, it is the polemicists’ condemnations of the Protestants who tolerated the adherents of the Church of Rome which suggest that coexistence in the English capital may have been much more common than historians have hitherto realised. While scholars have seriously challenged the whiggish paradigm that tolerance was a heritage of the Enlightenment by pointing to the many pragmatic accommodations ordinary people made to tolerate their ‘heretic’ neighbours, the historiography tends to portray London as an essentially intolerant society for Catholics.Footnote 5 For example, although Bill Sheils acknowledged that ‘London is poorly chronicled in comparison to the countryside’, he described the city’s Catholics as mistrusted, suspicious, and ‘shadowy figures to contemporaries’ who ‘survived under the cover of a constantly changing population’.Footnote 6 While this seems to imply that ‘neighbourliness’ and ‘everyday ecumenicity’ were in short supply in the capital, ironically it is vicious anti-Catholic polemic attacking tolerance and coexistence which suggests that intolerance is only part of London’s story.

Along the same lines, it is the polemicists’ reactions to how tolerance sustained a popular, vibrant, and outward form of Tridentine piety in embassy chapels which suggest that the Catholic religious experience in the capital was not as inconspicuous as we have assumed. Echoing wider assumptions that the proscription of the faith meant discreet worship in the home was the reality for most Catholics in England, historians often describe the religious observance of their compatriots in London as secretive and underground.Footnote 7 Carrying these themes forwards, Benjamin Kaplan argued in an insightful article that London’s embassy chapels can be compared to the clandestine churches in the Dutch Republic: disguised as domestic residences, their public presence was limited through ‘fictions of privacy’.Footnote 8 Although these are persuasive interpretations, evidence gleaned from the polemic published after the Blackfriars disaster suggests that ambassadors’ chapels in the English capital pushed, and sometimes broke, these boundaries in surprising ways. There may therefore be other ways of thinking about the principles which enabled these spaces to function as sanctuaries from persecution and why they could be so controversial.

Clearly, as a window to the tensions and contradictions surrounding coexistence and the visibility of Catholicism in late Jacobean London, the polemic published in the wake of the Blackfriars disaster is of considerable interest and importance to historians. This article will firstly demonstrate how the tracts reveal that tolerance was certainly not lacking in the English capital. It will then examine how the publications can be read as a reaction to the way ambassador’s chapels blurred, and sometimes broke, the boundaries between private and public religious practice through a vibrant, popular, and often quite visible form of Counter-Reformation Catholicism. Finally, the article outlines the relationship of these issues to the execution of the royal prerogative, and tensions surrounding what is known as the ‘king’s two bodies’. Ultimately, however, the polemic underscores how the circular relationship between tolerance and intolerance is crucial to understanding the complex dynamics which allowed embassy chapels to sustain a vibrant and communal form of Catholicism in the very heart of England’s Protestant kingdom, and why these spaces were so contested.

Before exploring these issues, it is important to consider the common characteristics and conventions of the publications the essay draws on. While all the tracts had similar messages, they differ in whether they provided warnings about the tolerance and visibility of Catholicism through a framework which interpreted the accident as God’s judgment on Catholic error and superstition, or if this was a divine intervention against Catholicism as an outright anti-religion, and therefore part of a cosmic battle between Christ and Antichrist.Footnote 9 It was no coincidence that the former stance taken by the licensed publications reflected the more internationally discreet, and less clearly defined, opposition to Catholicism favoured by a regime seeking alliances with Catholic powers, and which therefore could not condone polemic that portrayed the pope as Antichrist.Footnote 10 On the other hand, the latter apocalyptic narrative seen in the unlicensed publications echoed the tradition of ‘rabid anti-popery’ favoured by Puritan evangelical divines since the reign of Elizabeth I, which could only enter circulation through an illegal printer.Footnote 11 Thus, while the key messages about tolerance and Catholicism were essentially the same, the controversy was between two competing visions of anti-Catholicism that were current in Jacobean England at the time of the accident at Blackfriars. However, no matter which framework the authors chose, the pamphlets shed helpful light on interconfessional relations and Catholicism’s presence in the capital.

Coexistence, curiosity, and Christian charity in London

On the morning after the accident at Blackfriars, the coroner and jury returned a verdict that the calamity was caused by the excessive weight of the crowd on the defective main load-bearing beam supporting the attic. However, as Walsham remarks, ‘to pamphleteers, preachers, and at least a segment of the wider population, this was no “accident” or “natural” disaster’, but nothing other than a ‘foreordained act of God’.Footnote 12 While all the polemicists agreed it was a work of divine providence, there was much debate about what God’s message actually meant.Footnote 13 Although they came to different conclusions, the authors were united in the belief that it reflected divine displeasure with the Catholic faith and its community of believers.Footnote 14 Yet in addition to divine judgment on Catholicism as Walsham demonstrated, the authors believed that God had delivered several important warnings for Protestants about the dangers of tolerating Catholics.Footnote 15 While the varying responses to the Blackfriars calamity reveal anxieties about how tolerance of dissent threatened the ideal of a unified Protestant kingdom, the behaviours the authors attack expose many of the pragmatic concessions ordinary Londoners made to ‘get along’ with the Catholic ‘heretics’ in their midst.

Among many admonitions about tolerance, the polemicists deciphered God’s intervention at the French embassy as a clear warning for ‘lukewarm’ Protestants, including some who were so lacking in zeal that they had attended the fateful Catholic sermon on the day of the tragedy. Not only does this imply a concern about the existence of a section of the populace who were still ‘bewildered’, ‘confused’ or unconcerned by the numerous religious changes that had taken place after the Reformation, but it also perhaps points to Londoners who were indifferent to the presence of the city’s Catholics.Footnote 16 In his aptly named Digitus dei, for example, the evangelical preacher Thomas Scott linked the accident at Blackfriars with these inconstant waverers and wanderers. As he explained, those who might ‘cloake’ their ‘luke-warmnesse’ under the ‘pretence of modestie, patience, discretion, moderation, prudence, or temperance’ shall not ‘escape the Hand of God, [because] he will find out, and punish their falsehood and faintnesse in his cause.’Footnote 17 Similarly, in the Doleful even-song, the archbishop of Canterbury’s chaplain, Thomas Goad, asked those Protestants who survived the accident if this was not the ‘voice of God’ calling them ‘home from wandring after forraine Teachers, that lead the ignorant people captive … into the snares of danger, corporall, civill and spiritual.’Footnote 18 Just as the ‘lukewarm’ Protestants in the assembly at Blackfriars had fatefully learned, indifference to Catholicism was not only downright dangerous, it was soul destroying.

Applying similar assumptions, the polemicists additionally deciphered the Blackfriars tragedy as a heavenly warning for the Protestant Londoners who enjoyed amicable and sociable relations with Catholics. Nevertheless, in their detailed reporting of the tragedy, the authors provide helpful glimpses of the cross-confessional networks they go on to condemn. As the writer of The fatall vesper reported, sorrow spread across London after the downfall of the auditory because ‘here some men lost their Wives, women their Husbands, Parents their Children, Children their Parents, Masters their Servants, and one friend lamented the losse of another’.Footnote 19 Surely some of these relations must have crossed confessional boundaries given that both Protestants and Catholics were in the congregation? We might also draw similar conclusions about the breadth of everyday coexistence in the capital from the way Drury’s sermon was promoted on London’s grapevine to both Protestants and Catholics. As the evangelical minister of St Ann Blackfriars, William Gouge, pointed out, on the day of the accident ‘a common report went up and downe, farre and neare’ that Drury would preach, which attracted ‘many, Protestants as well as Papists, Schollers as well as others’.Footnote 20

However, in forging such relationships, Protestants were clearly playing with fire. As the author of Something written thundered, the Blackfriars disaster was divine judgment on Catholics because they were ‘antagonists, and inficious adversaries’ of the Almighty.Footnote 21 Therefore, in ‘plaine tearmes’ Protestants should ‘take God’s enemies for ours, and be no companions with the workers of iniquity’.Footnote 22 Taking a similar line, in his Foot out of the snare, John Gee, discredited Protestants’ sociable and amicable encounters with Catholics as risky and dangerous ‘snares’ that might ‘yeeld’ unsuspecting Protestants ‘unto the Popish perswasion’.Footnote 23 Gee admitted that he too was in the auditory of the doomed Catholic sermon after being led astray when ‘lighting upon some Popish company at dinner’ the previous evening, where his companions were ‘magnifying the said Drury’.Footnote 24 Such interactions were dangerous because of the ‘juggling knavery’ of priests, particularly ‘when they are drunke in good company’, which he had witnessed as their ‘companion’ on a number of ‘cheerful’ occasions.Footnote 25

Gee additionally undermined sociability with priests in London by associating this behaviour with disorderly women and an inversion of the patriarchal order, which Frances Dolan explained were common seventeenth-century tropes to taint the faith as different and inferior.Footnote 26 In particular, he salaciously claimed that priests secretly ‘creep into houses, leading captive simple women loaden with sinnes, and led away with diverse lusts.’Footnote 27 He also knew ‘many a poore Gentleman, that cannot rule his wife’ who go hungry because priests ‘must be fed with the daintiest cheere, the best wine, the best beer, the chiefest fruits that can bee got.’Footnote 28 While historians may be sceptical that men went hungry because of greedy priests invited into their homes by their dominant wives, both this claim and Gee’s own lucky escape from the disaster highlight how sociability with Catholics was tainted as risky and dangerous behaviour.

In condemning Protestants who were ‘supping with Satan’s disciples’, Gee very helpfully provides historians with glimpses of the way in which some Londoners stretched, or even broke, the boundaries reflected in contemporary casuistry which ‘differentiated between “necessary” and “voluntary” society with the wicked’.Footnote 29 As Walsham explained, this allowed ‘common’ and ‘cold’ forms of engagement with heretics like buying, selling and eating which ‘charity’ and ‘necessity’ required, but ‘prohibited “special” or “deare” kinds of interaction on the grounds they placed the soul in jeopardy.’Footnote 30 Clearly Gee had this in mind when he warned those ‘who have occasion to live neer the wals of these Adversaries, and it may bee, sometimes, of necessity, must converse and have some commerce with them, take heed you be not corrupted by them.’Footnote 31 As his own lucky escape from eternal damnation demonstrated, Protestants should have ‘no fellowship with the unfruitfull works of darkness.’Footnote 32

While calling for a Catholic medical practitioner may have been deemed necessary society, the polemicists’ censure of these interactions suggests that some Protestant Londoners had no qualms in crossing the confessional divide when they were ill. Gee, for example, undermined Catholic medical professionals by revealing the names and addresses of twenty-seven Catholic physicians, five apothecaries and three surgeons working in the capital in a later edition of Foot out of the snare.Footnote 33 Pointing to the popularity of Catholic doctors, the author of Something written bemoaned, ‘such is the corruption of time, and fantasticality of manners, that a Popish Phisitian is a man of rare quality’.Footnote 34 Underscoring how such engagement was risky for Protestants, Gee pointed to the sick Londoners who were supposedly tricked into spending large sums of money on masses after death, or hoodwinked to nominate priests as the beneficiaries of their wills after disinheriting their families.Footnote 35 This gives credence to Walsham’s suggestion that fear of death could be one explanation for why steadfast Protestants called for Catholic priests who were ‘renowned for effecting cures by means of relics, sacramentals and liturgical rituals’ with supernatural qualities which were popular with the laity.Footnote 36 But in calling this practice into question, and implicitly linking it to the Blackfriars disaster, the polemicists inadvertently reveal that the capital’s ‘medical marketplace’ was not necessarily divided along strictly confessional lines.

In a similar vein, the authors’ critique of everyday commercial interactions with Catholics indicates that some Protestant Londoners were unperturbed by crossing religious boundaries for commercial gain. This might be suspected from the author of Something written who sneered that some ‘penurious’ Protestant apothecaries actively sought out the ‘custome of Romish Phisitians’ to sell remedies to their Catholic patients by posing as Catholics.Footnote 37 To make this ‘matter more sure’ he scoffed that they even brought in the ‘whole family, wife, children, and servants to professe as much’.Footnote 38 In Hold fast, Gee pointed his finger at the booksellers who are ‘content to make Merchandise of Religions on both hands.’Footnote 39 However, for the author of Something written, who implicitly linked the Blackfriars tragedy to the ‘many papisticall pictures, medailes, & crucifies that have beene publikely sold’, such commerce was as good as wheeling and dealing with the devil.Footnote 40 Keith Luria’s study of early modern France revealed patterns of coexistence that were most likely when Catholic and Protestant neighbours subordinated religious allegiances to concerns for family alliances, business dealings, and civic affairs. In condemning such interactions, the polemicists perhaps expose a similar dynamic in London.Footnote 41

Although God had much to teach wayward Protestants about the dangers of tolerance, the polemicists also observed that the Almighty sent a warning to those who were curious to experience Catholic rites and practices. As Goad explained, some of those in the assembly at Blackfriars were not ‘Romanists, nor came thither out of affection to the Popish partie, but rather out of curiositie to observe their rites and manner of Preaching’.Footnote 42 Despite the deep-rooted anti-Jesuit mythology of the time, even the evangelically minded authors revealed that Protestants were drawn to the sermon at the French embassy because of Robert Drury’s positive reputation.Footnote 43 As Goad acknowledged, the ‘greatest lights of the Protestant Ministerie are but Glowormes’ in comparison to this ‘rare’ and ‘admirable Jesuit’.Footnote 44 However, Drury’s many positive qualities notwithstanding, Goad reminded Protestants that Pliny the Elder ‘paid deare for the satisfaction of his curiositie’ when he went to inspect the eruption of Vesuvius in AD79.Footnote 45 In a similar fashion, the author of Something written thundered that there was a ‘corruption of nature … in seeking after novelty’ and asked, ‘what had any Protestant to do with curiosity, when they knew how the men were slaine that looked into the Ark’ of the Covenant?’.Footnote 46

Clearly, contrary to the term’s modern positive overtones, in linking ‘curiosity’ with divine displeasure, the polemicists impute it with wholly negative attributes. Although Neil Kenny explained that inquisitive behaviour could be portrayed positively in secular discourse in the seventeenth century, it was often weaponised by the churches to denote defective behaviour of which they disapproved and which they wished to regulate.Footnote 47 As a result, it was the ambiguity of this term which made it ‘an arena within which some of the period’s basic anxieties and aspirations about knowledge and behaviour were thrashed out’.Footnote 48 Along the same lines, Adam Morton argued that ‘curiosity and condemnation were two sides of the same coin’ and reflected competing tensions around English experiences of foreign cultural exchange.Footnote 49 These same contradictions and ambiguities are laid bare in the condemnations of those who were inquisitive about Catholic rites and practices in London’s foreign embassy chapels. In this regard, the polemicists’ anxieties about curious ‘confessional tourists’ simultaneously points to the presence of a section of the populace who were genuinely intrigued by London’s religious diversity, and those who felt threatened by it.

Perhaps we might even dare to imagine that crossing the religious divide in this way may have been more common than we might assume, for at least some who lived in a cosmopolitan city which included the Catholic embassy chapels and the long-established and officially sanctioned French and Dutch ‘stranger’ churches.Footnote 50 Once again, it is the polemic published after the Blackfriars disaster that provides glimpses of these behaviours. In the Foot out of the snare, for example, John Gee remarked that on the morning of the tragedy he heard a Protestant sermon at ‘Pauls-Crosse’ before going to the fateful Catholic service in the afternoon.Footnote 51 Similarly, when the author of Something written compared Catholic religious practice at Blackfriars with the ‘fantasticall motions’ he ‘can witnesse in the Mercers Chappell’, he revealed that he had visited the London meeting place of the Italian Protestant community.Footnote 52 Implicit in these passing remarks is that crossing the religious divide in this way was both commonplace and unremarkable.

Ultimately, though, it is perhaps the polemicist’s attacks on fundamental Christian values of charity towards others which highlight the important role that these principles may have played in Londoners’ capacity to reconcile their everyday interactions with Catholics. As many historians have highlighted, universal medieval values of Christian charity and unity survived the Reformation and had a contingent relationship with contemporary concepts of ‘love thy neighbour’.Footnote 53 The importance and persistence of these beliefs was certainly reflected in the more moderate publications like Goad’s Doleful even-song, which argued that it was a duty for Protestants to show compassion to those who perished ‘out of natural humanitie’, ‘moral civilitie’ and ‘Christian charitie’ because they were ‘fellow-borne Countrymen’ who ‘professe the name of Christ, and devotion in his worship, howsoever tainted with many errors and superstitions’.Footnote 54 Similarly, the author of The fatall vesper advocated pity and compassion towards the Catholics who died and were injured.Footnote 55

In response, however, the author of Something written thundered that charity did not apply to Catholics because they were ‘Gods enemies’ who ‘not only speake blasphemies against the God of heaven, but practise horrible cruelties and iniquity against the saints on earth’.Footnote 56 As Catholicism was an ‘anti-religion’, the Blackfriars tragedy was nothing other than divine judgment on Catholic idolatry and part of a divine ‘controversie’ between ‘Christ and Antichrist’.Footnote 57 Likewise, although Thomas Scott acknowledged the Christian tenet that one should have ‘peace with all men’, he argued that it was impossible to ‘reconcile Light and Darkenesse, Hell and Heaven, God and Mammon, Christ and Antichrist.’Footnote 58 The Blackfriars disaster was therefore not only an apocalyptic warning for Catholics, but for those who ‘winke and shew our consent in their Sacriledge, by silence, like blind and dumbe dogges’.Footnote 59

Despite the inhumanity modern readers will instinctively detect in these statements, paradoxically it is the polemicists’ attacks on charitable values which perhaps expose their very presence in London society. Lending credence to this supposition, the authors of The fatall Vesper and The doleful even-song pointed out that at least some Londoners rushed to the scene of the accident at Blackfriars ‘out of charitie’ to help the injured.Footnote 60 Moreover, some degree of charity might likewise be guessed from those involved in the burial of some of the dead in the vaults and graveyards of Protestant churches, presumably with the acquiescence of ministers or church officials.Footnote 61 Similarly, the burial register of St Andrew’s Holborn recorded the names of twenty-three parishioners who perished ‘when hearing of a Sermon’ at Blackfriars and noting they were ‘of the parish but not buryed heere’.Footnote 62 Although Peter Marshall persuasively explained that Catholic burials in Protestant churchyards may not necessarily be an ‘assertion of membership in the “community”’, this particular example does seem to imply that some of those frequenting embassy chapels were known to their local parish church and were treated charitably in death despite attending a Catholic sermon.Footnote 63 While further research in parish records is clearly required, there is much to suggest that Londoners might also be compared to their compatriots in rural and regional areas who made similar accommodations, and behaved charitably towards their Catholic neighbours.Footnote 64

From this we might conclude that it is ultimately anti-Catholic polemic disapproving of tolerance and coexistence which suggests that London society was not as intolerant and hostile as we have imagined. As Anthony Milton argued, the ‘polarised view of Catholicism, which presented a simple black-and-white world in which the lines of confessional demarcation were strong, clear and not to be breached, existed within a society in which the same lines were constantly criss-crossed, redrawn, reconceived and tacitly ignored.’Footnote 65 Although much research of religious tolerance has investigated these trends in towns and villages in the regions, the polemic published after the Blackfriars tragedy indicates that they might also be applied to complex societies like London. Thus, even though the capital’s population grew exponentially through immigration in the seventeenth century, we should not automatically assume that this growth inhibited such behaviours. Certainly, Julia Merritt and Jeremy Boulton have found strong evidence of communal bonds in Westminster and Southwark, and there is no reason to believe that Catholic Londoners could not be accommodated in urban areas through the principle of ‘love thy neighbour’, a principle that gave rise to religious tolerance in other parts of the country.Footnote 66 This can certainly be assumed from the polemicists who not only fused providentialism with anti-popery as Walsham demonstrated, but also with religious tolerance to attack the many pragmatic concessions and compromises many Londoners made to get along with Catholics.Footnote 67 However, as will now be explored, the authors of the anti-Catholic tracts were at pains to point out that tolerance created room for the Church of Rome’s visible advance on the English capital.

The visibility of London Catholicism

As part of their warnings about tolerance, the publications uncover Protestants’ anxieties about the way London’s embassy chapels were important sites of community for many of the city’s Catholics at a time when the hearing or saying of mass was proscribed. Contrary to generalisations that London Catholicism was secretive and underground, I now want to explore how the polemicists’ hostility to illegal corporate devotions in these spaces reveals how they sustained and grew a popular and vibrant form of Counter-Reformation piety that would have been unimaginable in the regions. Not only does this lack of self-effacement have important implications for our understanding of the nature and character of London Catholicism, but it also complicates comparisons of these spaces with the clandestine churches in the Dutch Republic which limited their public presence through principles of privacy and discretion.Footnote 68

First and foremost, both the Blackfriars accident and the polemic published afterwards dramatically put the everyday appeal of communal worship in embassy chapels under the spotlight. This was certainly underlined when two of the pamphlets published the names, addresses and occupations of those who tragically plunged to their deaths on the day of the tragedy.Footnote 69 For example, listed among a handful of the elite were scores of ordinary Londoners, including ‘John Galloway, Vintener, in Clerkenwell Close’, ‘Abigail the maid’, ‘John Netlan a Taylor’, ‘Michael Butler the grocer’, and ‘Mistris Tompson, at Saint Martins within Aldersgate, Haberdasher’.Footnote 70 Confirming suspicions about the quasi-parochial character of the congregation, astute contemporary readers may have also observed that many of those who tragically died came from multi-occupancy households, including whole families with children and servants, from many parishes across the capital. Moreover, contrary to claims that the city’s Catholics were not a recognisable community at this time, the pamphlets brought to light that, although dispersed, scores of ordinary Londoners forged communal bonds when they participated in the unifying ritual of the mass.Footnote 71 This spotlight on those who attended the illegal Catholic sermon can only have fuelled contemporary concerns about the growth of ‘popery’ in the kingdom. However, as was now obvious, it was not just an issue for the Court; ‘popery’ was spreading like a disease in ordinary homes, streets, and neighbourhoods outside palace walls.

Nevertheless, it was not just the membership of the congregation, but also the scale of religious devotions in ambassadors’ houses which sustained perceptions about the overt and communal character of London Catholicism. Firstly, when two of the pamphlets reported that up to 400 people had assembled in Blackfriars for mass and vespers, they not only pointed to popular appetite for the cult of the Eucharist that defined Baroque piety on the Continent, but also to one of Catholicism’s most visible aspects in the English capital.Footnote 72 By their very nature, even if acting with caution, sizeable groups of people regularly coming to and from ambassadors’ residences must have had some degree of visibility in a large and densely populated city like London. Reflecting anxieties about this, Thomas Scott complained that ‘the Ambassadors houses were so many hives to which the drones resorted, who … fed upon the hony of the Bees’.Footnote 73 In part, it was the public character of corporate worship in the chapels of the foreign envoys which led him to conclude that Catholicism ‘had ‘all the outward glory of a vissible Church’.Footnote 74 While Scott’s criticism points to tensions surrounding the crowds of ordinary people who freely flocked to foreign embassies for their religious exercises, it also reveals one of the criteria contemporaries used to distinguish private from public religious practice.Footnote 75

Although it might be tempting to dismiss Scott’s remarks as a polemical exaggeration, commentators from across the confessional divide made similar analogies about the public character of London’s ambassadors’ chapels. For example, we can compare Scott’s complaints that Catholics ‘boasted of publicke assemblies’ with those of the Spanish representative, Deigo Sarmiento de Acuña, later the count of Gondomar, who claimed in a dispatch to Spain in 1613 that more people attended his chapel than a parish in Madrid.Footnote 76 Remarkably, one Catholic letter writer in 1622 even estimated that up to 1,600 people a day were going to mass at the Spanish embassy.Footnote 77 This did not escape the attention of the commentator and gossip John Chamberlain, who claimed in 1621 that there were almost as many attending mass in the Spanish embassy as were going to the Protestant church of St Andrews Holborn.Footnote 78 Moreover, when MPs attempted to petition James I about the causes of ‘popery’ in the kingdom in 1621, they, in part, blamed it on ‘the open and usuall resort to the houses’ and chapels of the foreign ambassadors.Footnote 79 The author of The fatall vesper even stated that the presence of Protestants in the congregation at Blackfriars meant that the Catholic sermon at the French embassy was a public meeting.Footnote 80 Once again, it is the points of tension around numbers and who was in the congregation which reveal the criteria contemporaries used to differentiate public from private worship.Footnote 81 But regardless of the actual numbers, or who flocked to embassy chapels, the perception that worship in embassy chapels had public characteristics is important.

These beliefs can only have been reinforced in the meticulous reporting on the type of corporate religious services that ambassadors and missionary priests offered local Catholics in the chapels of the foreign representatives. For example, both the Fatall vesper and the Doleful even-song revealed that Catholics had ‘daily’ access to the sacraments and all the ‘rites and ceremonies of the Romish Church’.Footnote 82 Crucially, the authors distinguished between the ambassador’s own ‘private’ chapel ‘reserved for the use of himselfe and familie’, and the ‘priests chambers’, a room ‘reserved for the sick’, and a dedicated ‘massing roome’ below the garret ‘whereunto Papists much resorted, to make confession, and heare Masse’.Footnote 83 Catholics had also gathered at Blackfriars for their ‘accustomed devotions’ where they confessed and received the sacraments in the morning, and were expecting to celebrate Evensong afterwards.Footnote 84 By all accounts, this was a sophisticated and established complex of considerable size in which Londoners enjoyed religious devotions that perhaps had more in common with Baroque piety on the Continent than the domestic and discreet religious practices which characterised worship in the regions.Footnote 85 It is against this backdrop that comparisons of embassy chapels with ordinary parish churches in London or on the Continent must be placed.

Yet it was also the way embassies functioned as important proselytising centres for growing the faith that sustained opinions about the presence of assertive Counter-Reformation practices in the capital. As the pamphlets disclosed, the French ambassador’s house was a dedicated preaching space of thirty to forty foot long and approximately twenty feet wide, and clearly large enough to hold the around 300 people of both confessions who came to Blackfriars on the day of the accident.Footnote 86 The author of Something written stated that there was daily preaching at the embassy, and that notice had been given the previous Sunday that Drury would be the guest preacher the following week.Footnote 87 Moreover, the theme of Drury’s sermon was the soteriological benefits of the Catholic sacraments as the only route to salvation, a topic which was presumably intended to influence the ‘wavering’ and curious Protestants who were in the auditory.Footnote 88 The author also complained that the Jesuits had specifically chosen the French ambassador’s residence to compete with, and supposedly attract parishioners away from, the neighbouring Protestant Blackfriars church where Gouge was the minister.Footnote 89 Once again, it is contemporaries’ feelings of competition with neighbouring parish churches and Protestants falling away which are important.

Along the same lines, the polemicists’ fears about the way missionary priests appealed to popular interest in the supernatural to convert Protestants by promoting ‘Catholicism’s superior thaumaturgic capacities’ reflect concerns about missionary efforts in the capital.Footnote 90 Among several examples, in his Foot out of the snare, Gee ridiculed two women who confessed in an examination that they had benefited from an exorcism with priests in the Gatehouse at Westminster which cast them into ‘extaticall raptures, and were possessed’ by the Virgin Mary, John the Baptist, the Archangel Michael and two Tyburn martyrs.Footnote 91 In response, Gee wanted to ‘premonish the ignorant, and feebler sort especially, who are like weak and silly flies, that they take heed how they be caught in such cobwebs’.Footnote 92 He also exposed anxieties about the way these ‘impostures’ were used to convince ‘weake wavering Protestants’ to join convents, monasteries and seminaries on the Continent.Footnote 93 So too does Thomas Scott, who portrayed the Blackfriars tragedy as divine punishment on those who ‘stand upon Miracles, for the confirmation of their falsehoods.’Footnote 94 This alarm about Catholic proselytising was particularly acute with prominent conversions of the Protestant elite, which, Arthur Marotti explained, could not be kept secret and were often publicly exploited for polemical purposes.Footnote 95 Nevertheless, as the tracts published after the Blackfriars disaster highlight, this does not mean we should underestimate very real concerns about Catholic missionary efforts in the ordinary streets and neighbourhoods across the English capital.

Similar conclusions about Catholicism’s active presence might be drawn from the polemicists’ fears about Catholics’ vigorous interventions in London’s public sphere, and the popularity of Catholic books, which were sometimes printed in, or distributed from, embassies.Footnote 96 In particular, John Gee devoted significant ink in The foot out of the snare to debunking miracle stories in Catholic publications freely available across London. Gee’s goal was to expose the ‘tricks and devices’ priests deployed to ‘hock-in the people’ in the ‘swarmes’ of Catholic books sent from the Continent, or published and sold locally through ‘Printing-presses and Book-sellers in every corner’ of the city.Footnote 97 For the likes of Thomas Scott, Catholic interventions in the public sphere were particularly galling and offensive.Footnote 98 Scott contrasted this active engagement with the regime’s censorship of anti-Catholic publications and sermons to restrict criticism of the Spanish Match in the early 1620s. As he pointed out, ‘no man should speake, write, preach, or practise any thing against [Catholic] designes, insomuch that divers have been imprisoned for discovering the Spaniards pride and hypocrisie, and many put out of countenance for invectives against the Kings friends, as the terme went.’Footnote 99 For many Protestants therefore, Catholics had greater freedoms to engage in London’s public sphere than the most steadfast adherents of the established Church in England.

Fears about Catholicism’s visibility can also be detected in the polemicists’ contempt for the way Catholics elaborated the sacred power of the city’s medieval landscape. As one of the surviving buildings of the ancient Dominican friary founded in 1278, the French ambassador’s residence had particular relevance for priests and the laity because, as the author of Something written reported, Catholics remembered that it was ‘once consecrated to pios usus, a publique Monasterie and sanctified religious house of Blackfriars in those days.’Footnote 100 Commenting on those who were interred in an unmarked grave at the scene of the accident, he was incredulous that ‘some have magnified the place of their burial, as being once a consecrated religious house!’Footnote 101 In this sense, the French embassy, like Holywell in Wales, can perhaps be considered another example of the way priests imported and adapted Continental Counter-Reformation practices to ‘harness and revitalise the ‘late medieval geography of the sacred’ by appealing to popular interest in the supernatural.Footnote 102 At the very least, the accident shone a light on one of the ways Catholics conceived and reimagined domestic spaces as sites of the holy. But, as Frances Dolan argued, this type of ‘floating and adaptive Catholicism was far more tenacious and disturbing than one rooted in property that could be defeated by displacement’.Footnote 103

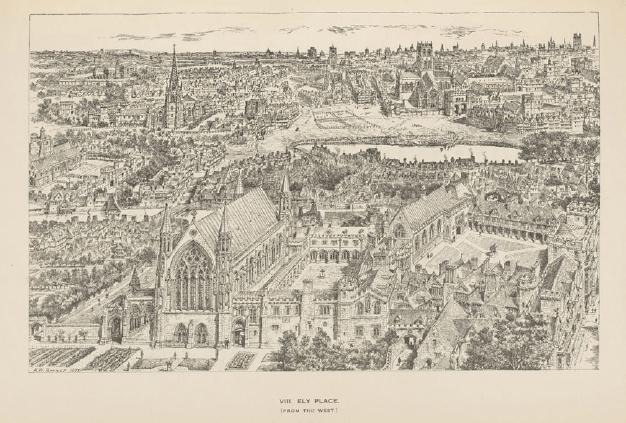

Anxieties about Catholicism’s appropriation of public spaces and buildings can only have been heightened when Catholic ambassadors even audaciously reclaimed ancient churches that were converted to Protestant places of worship after the Reformation. For example, when he was currying favour with Gondomar during the height of the Spanish Match negotiations, James I allowed the ambassador to occupy Ely House in Holborn, the former palatial residence and church of the Bishop of Ely which stood in the public domain (figure 1).Footnote 104 After the Protestant king of England defrayed the cost of reinstating this ecclesiastical building for Catholic worship, large numbers of his subjects predictably flocked to what, unofficially must have been, the first free-standing Catholic church in England since the Reformation. The irony of this was not lost on John Chamberlain, who said that ‘it cannot be some discountenance to religion to have masse as yt were publikely and ordinarilie said in a bishops chappell.’Footnote 105 Similarly, by at least 1626, the French ambassador had relocated to palatial Durham House, the historic residence of the Bishop of Durham, which had a medieval chapel facing the entrance to the Strand, and which was also a magnet for English Catholics.Footnote 106

Figure 1. Depiction of Ely House in the sixteenth century (now St Etheldreda’s Roman Catholic Church, Ely Place). Herbert A. Cox, Old London illustrated: A series of drawings by the late H.W. Brewer, illustrating London in the XVIth century, with descriptive notes by Herbert A. Cox. (London: The Builder, 1922), 43. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

At a time when the realities of persecution meant religious observance in the home was the norm for most Catholics in England, it is especially salient that large numbers of their compatriots in London heard mass in ecclesiastical buildings standing in the public domain. Undoubtedly, disquiet about Catholicism’s visibility reflected in the polemic published after the Blackfriars catastrophe might be read as reflection of the resentment and animosity this blatant and brazen usurpation of Protestant religious space must have provoked in many Londoners. What is more, even if they are exceptions, these examples nevertheless show that principles of privacy and discretion were not necessarily primary concerns for ambassadors.

It is the polemicists’ affront at Catholic processions to the execution site of Tyburn, reimagined as a sacred site of Catholic martyrdom, which suggests that such lack of self-effacement may have been far from unusual. As an illustration of this, in the The foot out of the snare, John Gee complained that on Good Friday in 1623 and 1624 groups of Catholics processed to Tyburn ‘in penitential manner’ with flagellants, and asked, ‘must this be done before hundreds of spectatours?’Footnote 107 Although Peter Lake and Michael Questier have demonstrated how executions at Tyburn could be exploited for polemical purposes, Gee reveals how Catholics may have publicly appropriated the site as sacred space on important dates in the religious calendar.Footnote 108 These claims appear less farfetched when we consider that Queen Henrietta Maria allegedly publicly processed ‘barefoot’ to Tyburn with her ladies in 1626 and prayed before the gallows with a rosary in her hands.Footnote 109 Reflecting the potential for such events to provoke strong reactions, the examination reports of a dozen Catholics arrested in 1614 divulge that hundreds of ‘pilgremes’ carrying hallowed boughs of box and yew participated in an elaborate Palm Sunday procession in, or possibly outside, the Spanish embassy in the Barbican.Footnote 110 While the controversy surrounding these extraordinary events points to a distrust of ‘a theatricality that turned public spaces into performance arenas’, these examples underscore how fears about Catholicism’s presence and visibility in public places were not simply situated in the abstract.Footnote 111

Benjamin Kaplan has demonstrated that clandestine churches in the Dutch Republic avoided insult by adhering to principles which limited their public presence through ‘fictions of privacy’.Footnote 112 The evidence for London’s embassy chapels suggests that they diverged from Kaplan’s paradigm in surprising ways. As contemporaries from across the confessional divide recognised, no matter where they took place, by their very nature, largescale corporate religious devotions in the city’s Catholic chapels had an inherently public character. Furthermore, both active proselytising in embassy chapels and Catholics’ adaptive appropriation of London’s landscape for their own religious purposes sustained perceptions of Catholicism’s assertive presence. In this regard, contemporary distinctions of what constituted private and public religious practice in a large and complex city like London were much more ambiguous and fluid than any simple dichotomy allows.Footnote 113 In the context of contemporary beliefs about religious orthodoxy and uniformity, it was therefore both the perceived and actual incursions in the public domain that made embassy chapels a source of tension reflected in the polemic.

Perhaps more importantly, the pamphlets reveal that devotional life in London’s chapels bore similarities to the ‘aspects of public and communal religiosity’ which Marc Forster argued defined Baroque Catholicism in southwest Germany.Footnote 114 That ambassadors, priests, and local Catholics could publicly challenge the ideal of religious orthodoxy in this way suggests that there was some degree of tolerance at official levels. In the context of the Thirty Years’ War and contemporary concerns about an international Catholic plot to extirpate Protestantism, the polemic might therefore be read as a reaction to what the authors believed was a tolerance of Counter-Reformation Catholicism’s visible advance on the English capital. But what gave rise to this extraordinary situation, and how was it possible for hundreds, and possibly thousands, of people to freely and openly frequent London’s embassy chapels at time when the public worship of Catholicism was proscribed?

Exterritoriality, the Spanish Match, and the king’s ‘two bodies’

As a seedbed of Catholic ‘heresy’ and ‘idolatry’, it was no coincidence for the polemicists that God had struck at the illegal congregation in the French embassy to deliver a heavenly warning about the dangers of tolerance. As only one of several embassies in London, the tragedy shone a spotlight on the way ambassadors’ chapels regularly attracted hundreds of Catholics for communal religious exercises, even though they were technically restricted for the personal use of the foreign agent and his entourage.Footnote 115 While the authors recognised that ambassadors’ residences were privileged places, ultimately, they interpreted the Blackfriars disaster as a divine warning for all those who tacitly permitted English Catholics to flock to these spaces, which implicitly included the king for not fulfilling his duties as a godly magistrate in enforcing religious orthodoxy. Not only does this have important implications for our understanding of how these spaces functioned as points of protection for Catholics, but also for the role both everyday Catholicism and its tolerance had on early Stuart religio-political tensions.

Although historians might be tempted to simply argue that embassy buildings were exempt from local laws through the concept of exterritoriality, this was an unknown construct in the early seventeenth century and therefore does not adequately explain the principles which protected the English subjects who worshipped in ambassadors’ chapels in late Jacobean London. As the legal historian Edward Adair demonstrated, exterritoriality was gradually built up over time through a combination of hard-won cases between ambassadors and the host regime, which eventually coalesced into a body of precedent that ‘told in the ambassador’s favour.’Footnote 116 It was therefore a personal immunity and did not include the house or building in which the foreign envoy resided. Only later in the eighteenth century was this extended to an ambassador’s house where one was to assume or pretend that it stood on the soil of the foreign agent’s homeland.Footnote 117

More recently historians of diplomacy have argued that the sociocultural practices and the personal relationships that constituted early modern political relationships were not just outcomes of foreign policy but were their very basis.Footnote 118 While they have not considered exterritoriality, their approach which treats ambassadors and monarchs as individual agents interacting with each other through strict social and courtesy codes is perhaps a more useful model for understanding the complex cultural dynamics underpinning the principles which shielded Catholics from persecution. This certainly appears to be very close to how the authors of the tracts understood why embassies functioned as protected spaces where a vibrant and communal form of Catholicism flourished.

For the authors of the anti-Catholic tracts, the French ambassador’s house was a privileged building because of the principles of honour ambassadors were afforded as high-status individuals representing foreign princes who had very personal relations with the English king. As the author of The fatall vesper explained, the residence of the French ambassador was protected from the mob by the City’s authorities after the accident so that he or ‘his servants should not suffer any detriment in their goods or persons, being jealous in this point of the Kings his own & the cities honour.’Footnote 119 Similarly, the author of Something written pointed out that Drury’s sermon took place in the French embassy because Catholics knew the service would be undisturbed ‘considering the reverence and respect, which all Ambassadors challenge in all nations, and upon all occasions.’Footnote 120 He also explained that Catholics worshipped securely in the French ambassador’s residence because the English were ‘better affected’ to him than ‘other Strangers’.Footnote 121 Thomas Scott likewise remarked that Catholics used the French embassy as ‘a cloake’ and ‘sanctuary’ from ‘the force and rage of the people’ because the English were ‘lesse suspecting that Nation for all our antient enmities then the Spanish.’Footnote 122

The role of honour and respect underpinning ambassadors’ immunities was additionally underscored by the English king in 1624, while implicitly pointing to the importance of the royal prerogative in upholding such privileges. James I responded to insults made to the Spanish ambassador in 1624 with a proclamation forbidding ‘insolencie, misbehaviour, incivilitie, disgrace or affront unto any ambassador’ because it ‘toucheth not only those Princes and States by whom they are imployed’ … [but] … the universall weale and tranquillite of all Kingdomes and States.’Footnote 123 As the king’s edict implies, ambassadors’ special rights and privileges, and the honour they deserved, derived from their status as representatives of the foreign princes with whom the English king chose to pursue amicable relations. Thus, it was the rank of the person who lived in the building, who they were representing, and what they were doing which was important. Yet even though the polemicists recognised some of the cultural codes protecting embassy chapels, they ultimately linked the liberties Catholics were enjoying with the king’s execution of the royal prerogative in the pursuit of an Anglo-Spanish dynastic alliance through the marriage of his son Charles to the Spanish Infanta. Before we consider some specific examples of this, we must firstly consider the political and religious context in which the Blackfriars tragedy occurred.

As Thomas Cogswell explained, the prospect of a future king of England marrying a Catholic princess and an alliance with Spain was anathema in the context of the hispanophobia sustained by memory of the Armada.Footnote 124 These anxieties were heightened in 1618 when the Bohemian Estates deposed James I’s son-in-law, Frederick V, from the throne of Bohemia in favour of the Catholic monarch, Ferdinand II; an event which precipitated the Thirty Years’ War.Footnote 125 To the horror of many Protestants, when the Spanish Army invaded the Palatinate in 1620 and deprived Frederick of his ancestral territories, James I pressed ahead with his pacifist approach to achieving peace in Europe through a dynastic alliance with Catholic Spain.Footnote 126 Incensed at public criticism of his approach, the king dissolved parliament in 1621, and banned the press and preachers from discussing matters of state.Footnote 127 Unable to rely on parliament, James agreed to several Spanish concessions, including a de facto toleration of Catholics in 1621 and a formal suspension of the penal laws in 1622.Footnote 128 It is in this context that the freedoms Catholics were enjoying at embassies must be seen, as well as the king’s reluctance to intervene to stop the practice.

Clearly the authors of the publications who linked Catholic liberties at foreign embassy chapels with the king’s foreign policies were skating on thin ice. The authors avoided severe punishment, however, because, as Walsham points out, they got their timing right.Footnote 129 Since the Blackfriars tragedy occurred when the Spanish Match negotiations collapsed after the Prince of Wales and Duke of Buckingham’s failed journey to Madrid to win over the Spanish bride in 1623, it was at a crucial juncture of Jacobean international relations and domestic religious policy.Footnote 130 As neither James I nor the pro-Spanish party on his Council had given up on alliance with Spain, the tragedy served as a convenient, if not grisly, part of a ‘blessed revolution’ to influence the king and parliament to change course.Footnote 131 One of the ways the polemicists attempted this was to mobilise public opinion through a public sphere religio-political controversy which linked the Blackfriars tragedy with divine displeasure on both the visible growth of Catholicism and its toleration in London, which implicitly included the king.Footnote 132 While on a superficial level the authors delivered warnings for ordinary Protestants who may have been coexisting with Catholics, ultimately, they were attempting to say that God had provided an important message for the English monarch.

In the licensed publications these messages were framed very carefully, albeit unambiguously, within the descriptive accounts of the accident. For instance, in Gods providence, Gouge concluded his account of the Blackfriars tragedy with a pointed reference to Catholics, who, ‘taking advantage at some present connivance, most audaciously and impudently, without feare of God or man did what they did.’Footnote 133 In the unlicensed publications these same messages were delivered much more forcefully within the language of anti-popery. From the safety of his exile in the United Provinces, Thomas Scott thundered that ‘the silence of all men at that time and in that action, provokes God to speake and to doe.’Footnote 134 Scott also made clear that Catholics frequented London’s embassy chapels ‘under the protection of the Prerogative of Kings’.Footnote 135 Referring to the king’s proclamation concerning ambassadors, he pointed out that affronts to foreign representatives were ‘soundly punished’ because it was ‘much against his Majesty, and the will of the State.’Footnote 136 Thus, whether delivered implicitly or explicitly, the authors delivered a rather audacious and very public challenge to the king’s execution of the royal prerogative, and for turning a blind eye to the large numbers of his subjects who resorted to embassy chapels. However, in criticising the policies of the king, the pamphleteers reveal the important role of royal ad hoc and de jure tolerance in allowing embassies to function as sanctuaries from persecution before the construct of exterritoriality was established.

Ultimately this was a debate about what is known as the ‘king’s two bodies’, whereby the monarch was both an individual and the personal embodiment of the Protestant state. In essence, therefore, the public sphere interventions in response to the Blackfriars tragedy reflect evangelical Protestant displeasure with the king for not pursuing foreign policy and his family’s dynastic ambitions along strictly confessional lines. This was because the proposed alliance and Spanish Match reflected the king’s personal wish which was contrasted against a much more impersonal vision of a Protestant regime and Church of which he was the head, and to which it was expected he should sacrifice his personal ambitions.Footnote 137 Or put another way, just as Protestants should not tolerate or coexist with Catholics in the parishes, the same applied to the Protestant king who should neither seek alliances or dynastic ambitions with Catholic powers. Likewise, he should fulfil his sacred duties as a godly magistrate and enforce religious orthodoxy through the execution of the penal laws to prevent people from flocking to London’s embassy chapels. The tensions between the king and his regime therefore reflect the same contradictions and competing impulses of everyday tolerance and intolerance writ large.Footnote 138

Conclusion

While Jacobean evangelical Protestants hoped that the winds of change that led to the abandonment of the Spanish alliance would put Catholics in their place, as long as English kings, and even Oliver Cromwell, pursued foreign relations along non-confessional lines, foreign embassy chapels were a near permanent presence in the English capital. Although the alliance with Spain was eventually shelved, it was replaced with other alliances and relationships with Catholic powers, most notably with France through the marriage of Charles I to Henrietta Maria. Even though monarchs occasionally attempted to prevent large numbers of people going to mass in the queen’s and ambassadors’ chapels when it suited them, often the pattern of turning a blind eye to this practice, as occurred during the Spanish Match negotiations, was to be continually repeated throughout the seventeenth century.Footnote 139 As the polemicists revealed, it was both the principles of ambassadorial status and honour, and the pursuit of diplomacy upheld by the royal prerogative which meant that London’s chapels simultaneously functioned as points of protection for Catholics and sites of tension for Protestants.

In this regard, the authors discussed here have highlighted the important role of the monarch tolerating embassy chapels in the long-term development of the construct of exterritoriality. As Garrett Mattingly explained, ‘probably the largest single factor in preparing men’s minds to this extraordinary fiction was the embassy chapel question’.Footnote 140 Essentially ‘if embassies were licensed to flout the most sacred laws of the realm, it was easier to think of them as not being within the realm at all.’Footnote 141 It was therefore the coalescence of a number of complex cultural and political dynamics which meant that worship in ambassadors’ chapels pushed, and sometimes broke, the boundaries from private to public religious practice in ways that would have been avoided in clandestine churches in the Dutch Republic. But this could also run the other way, as was the case in the 1640s when parliament was in the ascendancy and embassies were placed under greater scrutiny.Footnote 142 As the polemic makes clear, sometime the political climate gave rise to largescale communal worship, and sometimes it did not.

While the religio-political objectives of the Blackfriars pamphlets are well known, it is these vicious anti-Catholic tracts which indicate that some of our assumptions about coexistence, embassy chapels, and Catholicism in London should be qualified. In linking religious tolerance and worship in these spaces with divine providence and anti-popery, the polemicists indirectly cast much light on the unique nature and character of everyday ecumenicity and Catholicism in the English capital. Not only do the very behaviours the authors attempt to regulate imply that many Protestant Londoners subordinated religious allegiance to tolerate and coexist with Catholics, but some were even inquisitive about the vibrant and communal Counter-Reformation practices embassy chapels sustained. The polemicists’ anxieties also indicate that underpinning Londoners’ capacity to get along with ‘heretics’, were fundamental Christian values of ‘love thy neighbour’ and charity towards others. Perhaps readers might even dare to imagine that the polemicists’ apprehensions imply it was Londoners’ daily exposure to diversity and difference that enabled, rather than hindered, coexistence for at least some of its inhabitants. If so, then perhaps early modern religious tolerance was much more prevalent and more loosely defined than we have otherwise assumed.

While such tolerance was a form of intolerance in the sense that it was to ‘permit or license something of which one emphatically disapproved’, it nevertheless elicited a strong reaction in some quarters.Footnote 143 As the polemicists remind us, the pragmatic concessions and compromises to the reality of religious diversity in London existed within a set of ideological beliefs about the importance of upholding religious orthodoxy. Both the presence and ad hoc and de jure tolerance of everyday Catholics who enjoyed largescale communal worship in embassy chapels threatened this ideal of Protestant unity, which inevitably created the tensions reflected in the pamphlets published after the Blackfriars disaster. Viewed in this way, the polemic ultimately reflects these competing impulses, and the circular relationship between tolerance and intolerance at that time. What is more, the hostile responses to the Blackfriars tragedy suggest that it was both the perception of ‘popish’ plotting at Court and the tolerance of communal Catholicism beyond palace walls that does much to explain anti-popery rhetoric in the period.Footnote 144

Nevertheless, clearly London’s foreign embassies ordinarily protected by the royal prerogative played a crucial role in shielding Catholic dissenters from persecution, and sustaining a confident and, often, visibly Continental form of Catholicism in the capital. Although this created tensions, communal worship in these spaces persisted until official emancipation of Catholics in the nineteenth century when the establishment of their own ecclesiastical buildings was legalised. Could it therefore be that official and unofficial ad hoc tolerance of, and even curiosity in, London’s embassy chapels played a crucial role in the grudging acceptance of a unique and distinct cosmopolitan Catholic community and identity in London, and religious pluralism generally? Undoubtedly, further research on these spaces offers historians exciting opportunities to explore this and other questions related to interconfessional relations in London.Footnote 145