1. Introduction

Solvency II came into force on 1 January 2016 and included a transitional measure on technical provisions (“TMTP”) designed to help smooth in the capital impact over a 16-year period. The working party’s view is that the main intention of the TMTP is to mitigate the impact of the introduction of the risk margin, which significantly increases the technical provisions of firms, relative to their Solvency I Pillar 2 liabilities.

In the lead up to Solvency II many were thinking of the TMTP as a fixed amount set at 1 January 2016 which would very simply run-off over 16 years. Although the rules included provision for recalculation,Footnote 1 it seems fair to say that less thought had been given to the potential need to recalculate than to the amount of the TMTP on day 1. The need to recalculate so quickly after switching to the new regime was perhaps unexpected. However, market conditions in 2016 changed this view, so much so that TMTP recalculation has become a significant challenge for many UK firms in 2016. Severe interest rate falls meant sizable increases in firms’ risk margins. Without a recalculation of the TMTP, and assuming the absence of risk margin hedging, this creates a severe weakening of solvency positions.

A significant proportion of UK firms who hold a TMTP have now had at least one recalculation approved by the PRA.Footnote 2 Despite this large number of approved recalculations, there remains significant uncertainty in the industry around the approach and triggers for recalculation.

During 2016, the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA) Life Board established a working party to provide timely input on the topical issue of TMTP recalculation. The focus of this working party is to understand, the following impacts for regulated UK life firms:

∙ The challenges associated with the recalculation of the TMTP,

∙ What options are available to firms and the regulator to address these challenges, and

∙ What good practice looks like.

The main output of the working party is this paper.

1.1. Structure of This Paper

This paper contains material of a technical nature concerning the TMTP and is therefore necessarily detailed. The working party envisages that some readers may wish to reference specific sections of this paper and have included the following signposting to key sections of the paper below.

∙ Section 2 provides background information in relation to the TMTP, including an overview of the TMTP and the regulations in relation to TMTP in place.

∙ Section 3 describes why firms might need to recalculate a TMTP: it describes the main differences between the Solvency I and Solvency II technical provisions – which give rise to TMTP in the first place – and discusses what might cause the balance sheets to move in different ways.

∙ Section 4 discusses when firms might need to recalculate the TMTP. This includes deciding on whether an event constitutes a material change in risk profile; the need to put in place a recalculation policy; and the application process for demonstrating to the regulator that a material change in risk profile has occurred.

∙ Section 5 discusses how firms may carry out the recalculation. The working party has devised some high-level principles that it may be useful to bear in mind when performing the recalculation. The section then discusses areas to consider when recalculating the TMTP and how the Financial Resource Requirement (FRR) comparison test should be applied.

∙ Section 6 considers the implications of a TMTP recalculation looking forward and on the management of the business. This includes the Asset Liability Management implications, a potential timeline for the recalculating of TMTP and ways in which firms may communicate the TMTP externally.

∙ Section 7 summarises the overall conclusions of this paper.

Towards the end of the paper, the following sections are included:

∙ Section 8 includes references made in this paper.

∙ Appendix A outlines in detail the regulation in relation to the TMTP and a TMTP recalculation.

∙ Appendix B includes analysis of legal entities with written notices for approval to apply a TMTP, including how many of these legal entities have had a TMTP recalculation.

2. Background

The working party’s view is that the main intention of the TMTP is to mitigate the impact of the introduction of the risk margin, which significantly increases the technical provisions of firms, relative to their Solvency I Pillar II liabilities.

The risk margin was not a feature of Solvency I and firms had not generally priced in the cost of capital associated with a risk margin for all business written under Solvency I. This was particularly onerous for the UK life insurance industry given the significant bulk purchase annuity market and, until recently, compulsory purchase annuities for individuals.

As a result of this, the balance sheets of many UK insurance companies include significant volumes of business, which have a high value of risk margin relative to the value of best estimate liabilities (BEL). The working party’s understanding is that for immediate annuity business the risk margin is typically c10% of BEL, rising to around c25% of BEL for deferred annuity business, although these figures vary across firms and depend on prevailing interest rates at the time of calculation.

The TMTP provides firms with a “soft landing” into Solvency II regime over the transitional period of 16 years. By deferring this impact, it ensures the risk margin required on the back book of business does not have a material short term impact, for example, on the ability to continue marketing new policies to consumers, and avoiding investment decisions that would have a detrimental impact on policyholders or on the dividend paying capacity of proprietary firms.

The TMTP also mitigates other differences between the Solvency I Pillar 2 and Solvency II technical provisions and includes a financial resource requirement comparison test. The FRR is generally applied as the sum of technical provisions, non-technical liabilities and capital requirements under the respective measures. These concepts are outlined in further detail in the section below and throughout this paper.

2.1. Regulations

Details of the regulations relevant to the TMTP are outlined in “Appendix A: TMTP Regulation”.

2.2. Overview of Calculation

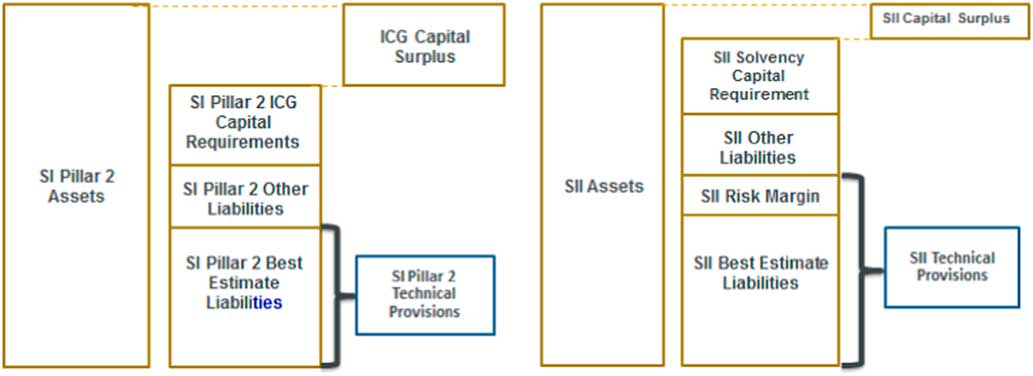

The working party believes the primary intention of the TMTP is to mitigate the impact of the introduction of the risk margin, which is not a feature of the Solvency I Pillar II regulatory regime. This can be illustrated by comparing the balance sheet and capital requirements under Solvency I Pillar 2 to those under the Solvency II regime prior to the inclusion of the TMTP as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Example comparison of Solvency I Pillar 2 and Solvency II balance sheets

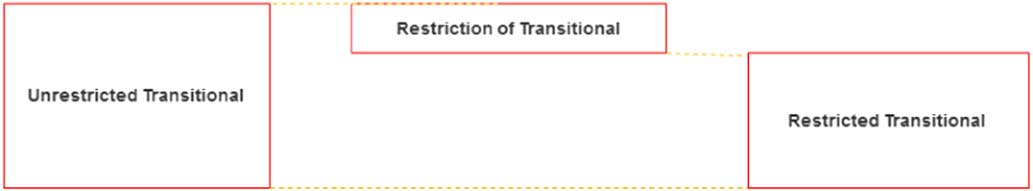

The value of the TMTP is determined by three steps:

1. The determination of the Unrestricted Transitional, i.e. the TMTP prior to the FRR comparison test.

2. A Restriction of Transitional is applied if the Solvency II FRR after allowance for the TMTP are below those of Solvency I. Solvency I is taken as the more onerous of Solvency I Pillar 1 and Pillar 2.

3. The Restricted Transitional is determined as the Unrestricted Transitional less any Restriction of Transitional (if applicable).

These steps are covered in more detail below.

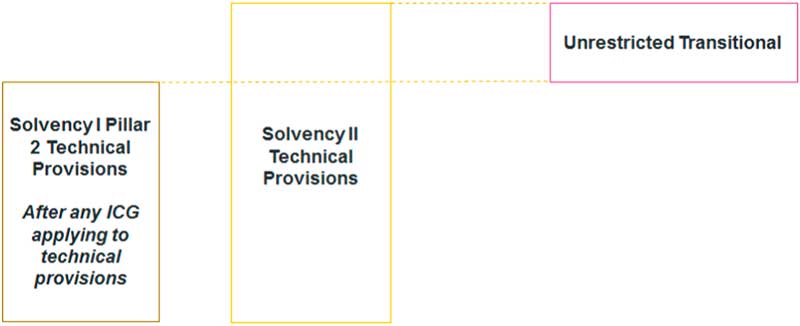

1. The Unrestricted Transitional is the excess of the Solvency II technical provisions, after deduction of the amounts recoverable from reinsurance, over the Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions, after deduction of the amounts recoverable from reinsurance and after any ICGFootnote 3 on technical provisions and is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 Unrestricted transitional

It is noted that the Unrestricted Transitional only applies to business written prior to the introduction of Solvency II.

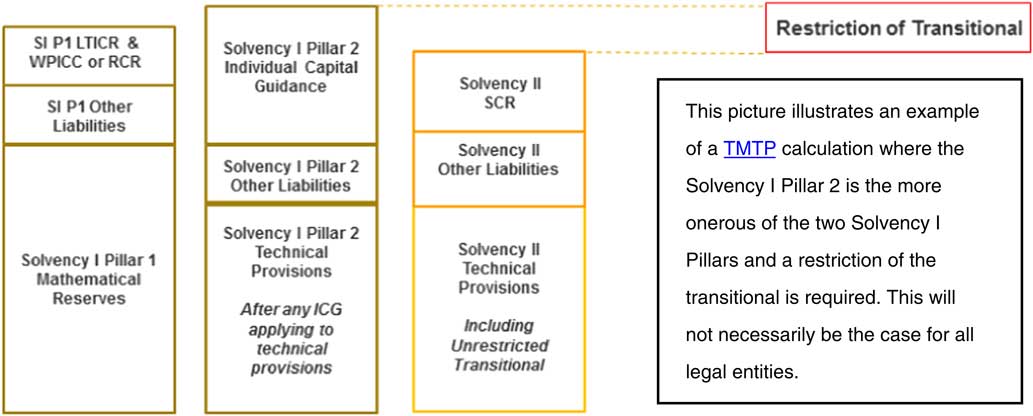

2. A Restriction of Transitional is applied if the Solvency II FRR, after allowance for the Unrestricted Transitional, is below those of the more onerous of Solvency I Pillar 1 and Pillar 2, as illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 Restriction of transitional

The FRR comparison test is generally expected to apply to all the business in the legal entity, and not just business written prior to the introduction of Solvency II. However firms are able to apply the FRR comparison test to only business written prior to the introduction of Solvency II, if they can demonstrate that the outcome would not be materially different to a full calculation.

For some legal entities the Solvency I Pillar 1 will be the more onerous and if this was the case then the Solvency I Pillar I FRR “bar” would be higher than the Solvency I Pillar 2 FRR “bar.”

The working party also notes that the relative levels of the FRR Pillars, i.e. Solvency I Pillar 1, Solvency I Pillar 2 and Solvency II FRR, change over time, reflecting the following:

∙ Transactional changes, for example Part VII transfers and revised reinsurance arrangements applying to business written prior to 1 January 2016.

∙ As well as more subtle change over time, for example reflecting the different sensitivities of each FRR Pillar to changes in operating conditions such as interest rates or equity levels.

Practical issues concerning the application of the FRR comparison test are outlined further in section 5.4.

3. The Restricted Transitional is determined as the Unrestricted Transitional less any Restriction of Transitional (if applicable), as illustrated in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4 Restricted transitional

2.3. Recalculation of TMTP

A significant number of firms who hold a TMTP benefit have now had at least one recalculation approved by PRA.Footnote 4 Despite this large number of approved recalculations, there remains significant uncertainty in the industry around the approach and triggers for recalculation.

Here we find that thinking about the TMTP recalculation under the areas of why, who, when and how helps to create good insights and discussion on the challenges firms are facing.

Why?

The TMTP was introduced to facilitate a smooth transition from Solvency I to Solvency II. However, the elements of the Solvency II balance sheet, and in particular the risk margin which the TMTP is designed to mitigate, are not static in value. Instead, they change dynamically over time reflecting changes in operating conditions (e.g. interest rates) as well as the impact of more substantive business changes such as a Part VII transfer.

This is particularly topical as during the first half of 2016 interest rates significantly reduced, which in turn increased the value of the risk margin across the industry reflecting its sensitivity to interest rates. It became clear that a number of firms would apply for a TMTP recalculation and indeed the PRA invited firms to seek approval for a recalculation as at 30/06/2016, subject to meeting their materiality criteria.

These issues are explored in more detail in section 3.

Who?

Following the reasons for why recalculation of the TMTP may be necessary, it is required to decide who will be responsible for monitoring the changes, and what governance needs to be followed.

From industry feedback that the working party has seen, it appears that the TMTP is owned by the firms’ Audit Committee, the Chair of which must write to the supervisor annually to attest that the use of TMTP remains appropriate.

However, while the responsibility for submitting the attestation rests with the Audit Committee, it can be seen that the Actuarial Function is usually tasked with the actual calculations of TMTP and the maintenance of the recalculation policy. The governance followed will vary from firm to firm and will need to be set out in the firm’s TMTP recalculation policy.

These issues concerning who is responsible for TMTP recalculation are not discussed further in this paper.

When?

Given the materiality of the risk margin and other elements of the Solvency II balance sheet the TMTP is designed to mitigate, firms need to be clear on when a recalculation of the TMTP is required. Recalculation will be required to:

∙ Reflect a material risk profile change, and,

∙ Reflect the biennial recalculation applied at 1 January 2018, 1 January 2020, etc.

In considering what constitutes a material change in risk profile there is an important distinction between recalculation as a consequence of operating changes and recalculations following management actions or corporate restructures – which need to dovetail with implementation planning.

These issues are explored in more detail in section 4.

How?

Firms need to develop solutions which allow them to recalculate the TMTP at future dates. The working party has identified the following main themes in relation to these recalculation solutions and these are outlined below.

These issues are explored in more detail in section 5.

2.4. Forward Challenges and Management of the Business

The existence of a TMTP, and the recalculation of the TMTP, has significant implications on the way that insurers manage their business. The working party has considered the following areas in more detail:

These issues are explored in more detail in section 6.

2.5. Other Calculation Considerations

The remainder of this section outlines other calculation considerations associated with the TMTP. These areas are not covered further in this paper – they are though still areas to keep in mind when recalculating the TMTP.

Homogeneous risk groups

Article 308d of the Solvency II level 1 text outlines that the deduction of the TMTP may be applied at the level of homogeneous risk group (HRG).

Firms will need to consider which HRGs to apply the TMTP to, if not all, and be able to robustly derive the TMTP components for these HRGs when recalculating in line with the requirements of TMTP regulation, most notably the PRA supervisory statement on TMTP SS17/15.

Allocation of TMTP to ring-fenced funds

A firm will need to consider how to allocate the TMTP, which is derived at legal entity level down to ring-fenced funds, which are typically (but not always) with-profits funds, and the remaining part of the legal entity.

The approach firms take to achieve this will be outlined in their initial TMTP application or any subsequent addendums.

Allocation of TMTP to risk margin and BEL

Firms need to allocate the TMTP between the risk margin and BEL, taking into account the relevant EIOPA Level 3 guidance. The relevant EIOPA Level 3 guidance covers the interaction between the TMTP and the Solvency II technical provisions, excluding the risk margin, where these Solvency II technical provisions are used as volume measures for other Solvency II calculations such as the Standard Formula operational risk capital requirements and the linear component of the Solvency II Minimum Capital Requirement (MCR). “Appendix A – TMTP Regulation” includes a reference to this EIOPA Level 3 guidance.

However, it is noted that when recalculating the TMTP after 1 January 2016 new business written after 1 January 2016 will generate a risk margin, but may be outside the scope of the TMTP. Therefore firms will need to form a view as to whether to:

∙ Allocate the TMTP to the total risk margin including both pre- and post-1 January 2016 business, or,

∙ Only allocate TMTP up to a maximum of the risk margin arising on pre-1 January 2016 business.

Furthermore, firms will need to consider the interaction and ordering of the allocation of the TMTP to ring-fenced funds and the allocation between risk margin and BEL.

Allocate to HRGs

For HRGs which are in scope of the TMTP calculation, firms will need to allocate the TMTP appropriately in Pillar 3 QRT disclosure forms and narrative reporting.

This is required in a number of places including the Solvency II balance sheet and for other, more granular disclosures, of the Solvency II technical provisions such as the life and health similar to life technical provisions QRT form (S.12.01.02).

PS11/17 Scope of the FRR comparison test

The PRA policy statement PS11/17 clarifies that the FRR comparison test should apply to all the business written in within a legal entity, and not just business written prior to the introduction of Solvency II.Footnote 5 The working party has been active in seeking a clarification on this important detail, and overall we view this as a positive step.

The working party notes that this change could lead to an unintended consequence where writing new business following the introduction of Solvency II could act to increase the value of the overall TMTP under certain circumstances. These circumstances include:

∙ The legal entity which the business is being written has a TMTP based on a restriction of the transitional, and,

∙ The Solvency II technical provisions are higher in value than the Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions. This is generally expected given the existent of a risk margin under Solvency II, which is not a feature of Solvency I Pillar 2.

Tax affecting the TMTP

The TMTP is considered to be a temporary or timing difference between IFRS and Solvency II technical provisions which in line with the accounting standard should be reflected in the Solvency II deferred tax liabilities. For proprietary firms, this increases deferred tax liability on the Solvency II balance sheet compared to those had there been no TMTP.

Increased deferred tax liabilities increase the potential loss absorbing capacity of deferred taxes (LACDT) and so can (if reflected in the capital calculation) lead to a reduction in the solvency capital requirement (SCR), compared to calculating the SCR without increasing the deferred tax liability arising from the TMTP.

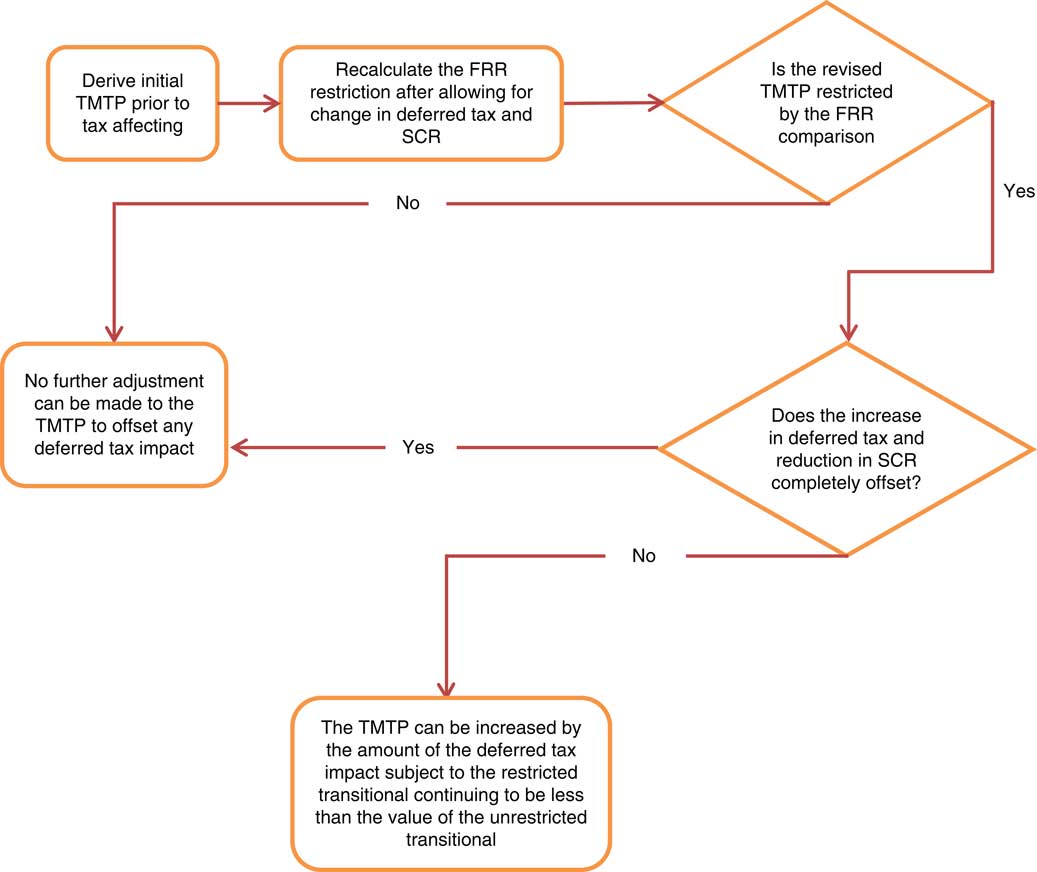

If the increase in deferred tax liability exceeds the increase in LACDT this increases the overall FRR, compared to not allowing for increased deferred tax, potentially reducing the amount of restriction. However, if firms do not allow for the deferred tax impact in this manner and try to allow for it as an end piece adjustment then some circularity and complexity is introduced. Figure 5 below outlines a possible process to help manage this.

Figure 5 Tax affecting the TMTP

It is noted that chart below is intended to provide a relatively high-level view of the interaction between deferred tax and the TMTP, and is not intended to be a substitute for expert tax advice. It is noted that it ignores complications associated with the recognition of a “net” deferred tax asset on the Solvency II balance sheet.

Under Solvency II a “net” deferred tax asset, i.e. the deferred tax asset in excess of the deferred tax liability, is not generally recognised on the balance sheet results and is reduced to zero. This may occur for a Solvency II balance sheets prior to the TMTP, where the introduction of a TMTP would first offset any “latent” deferred tax asset, before resulting in a “net” deferred tax liability.

3. Why Would Firms Want to Recalculate the TMTP?

The main reason for recalculating the TMTP is to ensure that the TMTP is still appropriately aligned to the differences in Solvency I and Solvency II technical provisions it is designed to mitigate. In particular, it is noted that these differences, and in particular the risk margin, are not static in value and dynamically change over time reflecting changes in operating conditions and/or more substantive change like a Part VII transfer.

To consider why firms would want to recalculate the TMTP, the working party has considered the main differences between the Solvency I and Solvency II technical provisions that give rise to the TMTP. Any change in these factors could alert to the need to recalculate the TMTP and firms will need to consider the impact from each of these factors when they perform TMTP recalculations. The main differences are:

(i) Risk margin;

(ii) Basic risk-free rate;

(iii) Solvency II matching adjustment (MA) and the Solvency I Pillar 2 illiquidity premium;

(iv) Solvency II volatility adjustment;

(v) Contract boundaries;

(vi) Treatment of ancillary expense companies;

(vii) With-profits future shareholder transfers;

(viii) With-profits planned enhancements.

Each of these is discussed in turn below.

It is noted that this list reflects the main differences in Solvency I and Solvency II technical provisions and is not intended to be exhaustive.

In addition, this section also covers related areas of note including changes which could impact any of the above items (3.9) and stress and scenario testing (3.10).

3.1. Risk Margin

The risk margin is a new requirement introduced by Solvency II. In theory, the risk margin is the additional amount above the BEL required to transfer the business to a third party. The risk margin represents the cost to the reference undertaking of providing capital to cover its SCR for non-hedgeable risks over the expected lifetime of the business. It is calculated by projecting the costs of holding capital in respect of non-hedgeable risks over the lifetime of the business, based on a fixed cost of capital, and then discounting by the Solvency II curve to find the present value of the costs.

As the risk margin is the discounted present value of capital costs, it can be extremely sensitive to interest rates. This can be significant for firms whose capital requirements run-off slower than its BEL. This can manifest itself as a double impact for risks where the capital requirement is a function of interest rates, e.g. longevity risk. In this situation, a fall in interest rates would both increase longevity capital requirements and also increase the present value of future costs. Although it is noted that this may be partially mitigated through a faster run-off of future longevity stresses.

The risk margin may also change as a result of a change in the projection of the capital requirements in respect of non-hedgeable risks. This could be because the company in question changes how it calculates its capital requirements: for example because the company switches from standard formula to internal model; because the company changes its internal model calibrations; or because the standard formula calibrations change.

The company may also change its risk margin methodology calculation. For example, some companies use a “risk carrier” approach to project the capital requirements for non-hedgeable risks. This assumes that a particular component of the capital requirements runs off in line with some other item that has already been projected – for example, the expense risk SCR component might be projected to run-off in line with the number of policies. If the company changes its choice of risk carrier, the risk margin may change.

The risk margin will also change as the business runs off. It is driven not just by the speed of the run-off – which affects all of the items in the list above – but also by the way in which the balance of risks changes. For example, if a portfolio of protection business runs-off faster than a portfolio of annuity business, then the allowance for diversification between the two lines of business will change, impacting the risk margin.

Finally, the size of the risk margin will be affected by the company’s use of appropriate reinsurance, with a credit worthy counterparty. If the company reduces its exposure to longevity risk, mortality risk, lapse risk or any other “non-hedgeable” risks through its use of reinsurance then the risk margin will decrease.

3.2. Basic Risk-Free Rate

For most currencies, including GBP, the Solvency II basic risk-free rate is based on swap yields. Solvency I Pillar 2 was less prescriptive with some firms basing their risk-free rate on swap yields and other firms basing their risk-free rate on gilt yields. The gilt-swap spread may therefore lead to differences in technical provisions, which affect TMTP. It follows that changes in the gilt-swap spread may lead to a firm needing to recalculate its TMTP.

In addition to this, there are other differences in the basic risk-free rate structure under Solvency II which are likely to differ to Solvency I. These include:

∙ The use of swap yields under Solvency II for GBP denominated liabilities. As noted above, this was not prescribed under Solvency I Pillar 2.

∙ The inclusion of the Solvency II Credit Risk Adjustment. This is a deduction to the Solvency II risk-free curve to allow for the additional credit risk which is perceived to be implicit within the swap curves.

∙ The inclusion of the Solvency II Ultimate Forward Rate, which has a more material impact on Euro denominated liabilities, than Sterling denominated liabilities, but may impact UK legal entities with non-domestic branches.

∙ The Solvency II Matching Adjustment and Volatility Adjustment (VA), which are outlined in more detail below.

Any material changes in the differential between the basic risk-free rates applied under Solvency I Pillar 2 and applied in Solvency II could lead to a recalculation of the TMTP.

3.3. Solvency II MA and the Solvency I Pillar 2 Illiquidity Premium

Both the Solvency I and Solvency II risk-free rates could be adjusted by either the illiquidity premium or the MA. These items are conceptually similar but there are some important differences between the two.

The overall purpose of the Solvency I Pillar 2 illiquidity premium and Solvency II MA is to allow firms to benefit from the excess spread over the risk-free rate on assets backing liabilities, where assets are “bought to hold” to maturity. In order to benefit from this excess spread over the risk-free rate firms must ensure that assets and liabilities are suitably well matched and in particular the liabilities are predictable in nature and unlikely to result in a future liquidity demand which would require a forced sale of assets to meet.

The method of calculation is more prescribed under Solvency II, while under the Solvency I Pillar 2 regime firms had more discretion to develop their own approaches. For example, the working party understands that some firms did not make an allowance for the costs of downgrades in their Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions: only the costs of defaults. In addition, firms may have calibrated their Solvency I Pillar 2 default allowances using different data to that used to calibrate the Solvency II allowance, or may have used a different approach – such as linking expectations of future defaults to the size of the spread.

There may also be minor differences in the way that the spread on the assets is determined under Solvency II compared to how it was determined under Solvency I Pillar 2. For example, companies were only able to include some of the cash-flows arising from callable bonds into account when calculating the MA. The MA and illiquidity premium may therefore change by different amounts in response to movements in the price of callable bonds.

A further example relates to the treatment of illiquid assets such as Equity Release Mortgages, Commercial Mortgages or Infrastructure assets. Under Solvency I Pillar 2 firms would have developed internal ways of measuring the required deduction for “defaults,” including more bespoke risks associated with these assets, and include a best estimate view of this deduction in the calculation of BEL. Under Solvency II, firms are required to map these assets to Fundamental Spread “buckets,” which have been calibrated using corporate bond data. This can result in differing levels of expected “defaults” in the Solvency I Pillar 2 and Solvency II technical provisions.

A further way in which the difference between the MA and illiquidity premium could change over time would be if there is a change to the assets used to back the liabilities. This may happen as a result of trading activity or simply as a result of the assets and liabilities running off over time.

Finally, if a firm does not use a MA, but seeks to apply for a MA to benefit from lower Solvency II technical provisions, a recalculation of the TMTP would be expected to largely offset any benefits arising on business written prior to 1 January 2016. It is noted that change in use of MA is included as an example of a material risk profile change in the PRA’s supervisory statement on TMTP Recalculation (SS6/16).

3.4. Solvency II Volatility Adjustment

Where a MA is not applied, a further application can be made to adjust the Solvency II discount rate to include a VA. This is an addition to the basic risk-free rate linked to the level of spreads observed in the market. It is determined by EIOPA based on the spreads on a representative portfolio of assets – not necessarily the assets held by the firm. The VA is most commonly used for with-profits business and annuity liabilities that are not eligible for the MA.

There was no equivalent of the VA under Solvency I Pillar 2 and any changes to the VA will therefore impact on the TMTP. These changes could arise either from market movements in EIOPA’s notional portfolio, changes in sensitivity due to changes in economic conditions or from EIOPA changing the way that it calculates the VA.

It is noted that firms may have chosen to apply for a VA where an illiquidity premium was applied in their Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions. The MA application may have been deemed too onerous to apply for, or an MA application may have been submitted but not approved. It is noted that for UK business use of the VA requires a formal application and regulatory approval, although this process is considerably less onerous than the equivalent MA application and approval process.

As per MA, a firm seeking to change their usage of the VA would need to consider the impacts from a recalculation of the TMTP. It is noted that change in use of VA is included as an example of a material risk profile change in the PRA’s supervisory statement on TMTP recalculation (SS6/16).

3.5. Contract Boundaries

Solvency II introduced limits on the extent to which future premiums could be allowed for in the valuation of insurance policies. This means that the Solvency II valuation generally assumes that policyholders will continue to pay premiums for a shorter period than was assumed in the Solvency I Pillar 2 valuation. The impact of this is generally most significant for unit-linked and group-life business.

As time moves on and premiums outside the Solvency II “contract boundary” are received the contract boundary difference between Solvency I Pillar 2 and Solvency II technical provisions would reduce. The deduction recalculation at a date after 1 January 2016 would therefore include a reduction from contract boundary impacts.

As a result of the different contract boundaries, the Solvency II and Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions will generally change by different amounts as interest rates move. This is simply a result of the movement in the yield curve affecting a different set of cash-flows. This will have a knock-on effect on the TMTP. It is generally to be expected that any change in interest rates would have a lower impact on contract boundary differences than it would on the size of the risk margin.

Any subsequent changes from using a short to long contract boundary will of course also affect the TMTP: since this will impact Solvency II technical provisions but not Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions.

3.6. Treatment of Ancillary Expense Companies

Where a firm uses an ancillary expense company, which charges fees to the legal entities for expense services, and this ancillary expense company is not a subsidiary of the legal entity, this can result in differences in the Solvency I Pillar 2 and Solvency II technical provisions. This difference results from the use of expense assumptions in Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions which “look through” to the underlying expenses incurred and contrasts with Solvency II technical provisions which are valued based on the fees charged by the ancillary expense company.

3.7. Future Shareholder Transfers in Respect of With-Profits Business

Shareholder transfers dependent on with-profit business participation are not liabilities in Solvency II technical provisions as they generally were in Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions. Again the working party has observed, a variety of approaches taken in the Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions.

The different treatment may have made a negative contribution to the initial deduction. As time moves on and the transfers are paid the contribution to the difference in Solvency I Pillar 2 and Solvency II technical provisions will reduce and so on recalculation the TMTP would, other things being equal, increase.

The issues concerning with-profits future shareholder transfers are outlined in more detail in section 5.4.3.

3.8. With-Profits Planned Enhancements

There are various ways in which distributions may be made to with-profits policyholders. Under Solvency II, only some types of future distribution are allowed for when calculating technical provisions for with-profits business; other types of distribution are only recognised when they are deemed permanent and fully recognised in the asset share. This differs from the Solvency I Pillar 2 regime, where firms typically allowed for all types of future distribution in their technical provisions, although the working party understands that no single Solvency I Pillar 2 approach existed.

Recognition of with-profits planned enhancements as liabilities in Solvency I potentially reduces the TMTP given they are not recognised in Solvency II technical provisions.

3.9. Changes That Could Impact on Any of the Items Above

In addition to the specific factors highlighted in each of subsections 3.1–3.8 above, there are of course factors that could affect any of the items.

Anything that affects the number of policies on the books will have an impact on each of the areas of difference between the Solvency II and Solvency I Pillar 2 technical provisions. A change in the amount of business in force could result from the acquisition or disposal of a block of business or from decrements such as deaths, surrenders, or lapses being different to expected.

3.10. Stress and Scenario Testing

As part of a firm’s effective risk management process, stress and scenario testing will be undertaken. The TMTP will need to be recalculated under a range of different outcomes. However, firms should consider the results on both a “static” basis and a recalculated basis as PRA approval to recalculate would still be required under stressed conditions. The results of the stress and scenario testing would likely feature in the firm’s ORSA (Own Risk and Solvency Assessment).

The PRA’s consultation paper CP47/16 highlights the need, where the TMTP is a material component of own funds, for firms to “analyse the material components and drivers” and also to consider “how those components may change over time and under a range of operating conditions”. The PRA expect this analysis to be included as part of the ORSA and to be available to the PRA on request.

The ORSA should include projections of own funds and required capital over the business planning period. It would be expected that, where a TMTP is in use, the business planning process would already be considering how the TMTP may change over the business planning period.

4. When to Recalculate the TMTP

4.1. Introduction

A recalculation of the TMTP can occur in the following circumstances:

∙ Every 2 years after 1 January 2016 (section 4.2.1); or

∙ More frequently to reflect a material risk profile change (section 4.2.2)Footnote 6

In considering what constitutes a material change in risk profile, there is an important distinction between recalculation as a consequence of operating changes and recalculations following management actions or corporate restructures – which need to dovetail with implementation planning.

The working party believes the primary evidence demonstrating that there has been a material change in risk profile is the impact on solvency coverage of a pro-forma position allowing for a recalculation of the TMTP, relative to the solvency coverage based on the TMTP derived at the last recalculation date and run-off appropriately. If this change in solvency coverage is greater than 5% then it should be considered that there has been a material change in risk profile in line with the criteria outlined in the PRA’s supervisor statement SS6/16.

In terms of communicating a material change in risk profile, both to the Board and the regulator there may be benefit from turning the solvency coverage ratio triggers into a range of equivalent single factor stresses so that it is possible to understand and foresee the sort of change in, for example, interest rates that might lead to a 5% solvency coverage trigger being breached. In particular, this expression may help those who are not close to the calculation understand it in business terms.

Other external factors are also important to consider where the TMTP is of material importance to solvency coverage or a firm’s risk appetite, for example: alignment of a recalculation with reporting dates; and dividend strategy. Communication strategy within external disclosures is also very important, particularly in the early years of Solvency II when the TMTP will be new to end-users, such as market analysts, and is likely to be a material component of a firm’s Solvency II balance sheet. Firms should therefore give careful consideration to the level of information disclosed and ensure that is appropriate for its intended audience.

This creates a bit of a chicken-and-egg conundrum and demonstrates the real need for a quick and well-understood process for application for a TMTP recalculation. The financial statements should reflect a true and fair position…so is reporting with or without a TMTP recalculation true and fair?

It was entirely conceivable that firms who accepted the PRA’s invitation to recalculate at mid-year may wish to again apply for a recalculation at year-end.Footnote 7 On the other hand, those who have not yet recalculated during 2016 and are currently in the process of applying to do so have been asked to recalculate at the 2016 mid-year position to create a consistent comparison against those firms who did recalculate.

Supervisory approval is required to recalculate in the event of a material change in risk profile and will require re-calculation triggers to be defined in a firm’s recalculation policy, which is covered in section 4.3. The application process for gaining approval is considered in section 4.4.

4.2. Circumstances for Recalculation

4.2.1. Recalculation every 2 years

SS6/16 indicates that the PRA expects firms to carry out a recalculation every 2 years from the date of implementation of Solvency II (1 January 2016) over the TMTP’s 16-year lifetime, irrespective of any recalculations resulting from a material change in risk profile (which are discussed in section 4.2.2 below).

Is resetting of TMTP on recalculation every 2 years compulsory even if the change is not material?

The purpose of the biennial recalculations is said to be to keep alignment between the relief afforded by the TMTP and those elements of technical provisions for which the TMTP was designed. No mention is made to materiality for biennial calculations which is in contrast to recalculations for changes in risk profile for which the SS indicates that only if the solvency cover ratio changes by 5% or more would the PRA expect firms to apply for a recalculation. This could be taken to imply that the TMTP would be reset on two yearly recalculations even for small changes. Firms could though presumably discuss this point with the PRA.

Is supervisory approval required to recalculate every 2 years?

For the biennial recalculation, it is currently unclear as to whether a firm will have to follow the same process as for an application to recalculate following a material change in risk profile or whether a firm can recalculate without requiring PRA approval. The regulator’s requirements for such a recalculation should be discussed with a firm’s supervisor and could be reflected in its policy. The policy could also include the conditions under which a firm would not recalculate its TMTP at a biennial review date (e.g. immateriality triggers).

4.2.2. Material change in risk profile

Outside of the regular biennial recalculation cycle, the TMTP can be recalculated if a firm can demonstrate that a material change in its risk profile has occurred. A firm’s definition of a material change in risk profile needs to be defined in its recalculation which is discussed in section 4.3 below.

What sort of circumstance may result in a material change in risk profile?

SS6/16 states “In the PRA’s view a variety of circumstances may give rise to a material change in risk profile. Risk profile changes that may trigger a recalculation include but are not limited to the following examples:

∙ acquisition or disposal of business priced and written before 1 January 2016;

∙ material changes to the reinsurance programme for business priced and written before 1 January 2016;

∙ unexpected changes to the run-off pattern of the insurance obligations in scope of the transitional measure;

∙ a change in the firm’s use of either the matching adjustment or the volatility adjustment; or

∙ changes in operating conditions, including in interest rates or market prices of other financial assets leading to revised market risk exposures, or crystallisation of an insurance risk exposure, e.g. a change in projected mortality experience.”

The list above can be classified under two main headings, changes related to: a change in operating conditions (third and fifth bullets) that are generally outside a firm’s own control; and more structural changes that are likely to be initiated internally (first, second and fourth bullets).

What level of evidence would be required to support a change in risk profile needing recalculation?

A compelling argument that the recalculation would have a material impact on the entity’s balance sheet is required. The SS indicates that the PRA’s assessment of a material change in risk profile will take into account the:

(i) change in risk-free rate (expect 50 bps or more in the 10-year rate);

(ii) impact on solvency coverage ratio, and

(iii) impact on recalculation of solvency coverage ratio (expect 5 percentage points or more) at a legal entity level.

The changes in the risk-free rate are expected to be sustained. A sustained change is defined as one that has persisted over a significant period of time or driven by factors that are likely to persist over a significant period of time. The PRA also note that changes in credit spreads could be relevant in this assessment but this depends on a firm’s asset holdings.

The PRA expects firms to provide evidence when applying a recalculation taking into account the PRA’s own three assessment criteria described above. For example, to explain materiality of the change in solvency ratio by comparison to expected frequency and likelihood of occurring. The PRA states that it is their view that the expected frequency and likelihood of changes occurring in the solvency ratios and own funds are key indicators in determining what constitutes a material change in risk profile.

It may be appropriate for a firm to have different thresholds to those outlined in the SS, as discussed, and if this is the case these should be discussed with the firm’s regulatory supervisor. Evidence of a breach of the thresholds set out in the firm’s recalculation policy will need to be agreed internally and then provided to the PRA as part of the recalculation application.

At what level in a firm’s business hierarchy should the TMTP recalculation impact on solvency coverage ratio be assessed?

The PRA SS on the recalculation of the TMTP outlines that the PRA would not generally expect a firm to apply for a TMTP recalculation where the increase or decrease in solvency coverage ratio at a legal entity level is less than 5 percentage points.

The working party has identified a situation where assessing the impact of a pro-forma TMTP recalculation on solvency coverage ratio at a legal entity level may not be fully appropriate in certain instances. Specifically for firms with ring-fenced funds (RFF), a legal entity solvency coverage ratio does not necessarily demonstrate a change in risk profile as a recalculation of the TMTP does not impact the surplus assets available due to RFF restrictions. Furthermore, RFF business dilutes the impact on the coverage ratio of a recalculation of the TMTP. The simplistic example below demonstrates this:

Before a recalculation of the TMTP, the firm’s position is as follows:

(i) TMTP in respect of non-RFF business=£1,000 m, with own funds of £3,000 m and SCR of £1,500 m so non-RFF coverage ratio=200%.

(ii) TMTP in respect of RFF business=£500 m, with own funds of £1,000 m and SCR of £400 m so RFF coverage ratio 250%.

(iii) Prior to recalculation of the TMTP, the legal entity solvency coverage ratio=own funds of £3,400 m, with SCR of £1,900 m=179% (i.e. lower than the non-RFF ratio in isolation because there are no surplus assets from the RFF taken into account when determining the ratio).

Risk profile changes have occurred which could impact the TMTP for RFF business differently to that of non-RFF business such that:

(i) TMTP in respect of non-RFF business=£950 m, with own funds of £2,950 m and SCR of £1,525 m so non-RFF ratio=193% (i.e. reduction of 7 percentage points in comparison to pre-recalculation)

(ii) Say there are three scenarios for RFF business, one where the TMTP reduces (i.e. (a) below), one where the TMTP increases (i.e. (b) below) and one where the TMTP is unchanged (i.e. (c) below)

a. TMTP in respect of RFF business=£480 m, with own funds of £980 m and SCR of £400 m so RFF ratio=245% (i.e. reduction of 5 percentage points)

b. TMTP in respect of RFF business=£520 m, with own funds of £1,020 and SCR of £400 m so RFF ratio=255% (i.e. increase of 5 percentage points)

c. TMTP in respect of RFF business is unchanged so RFF ratio=250%

(iii) After recalculation of the TMTP, the legal entity solvency coverage ratio=own funds of £3,350 m, with SCR of £1,925 m=174% (i.e. reduction of 5 percentage points) regardless of whether scenario a, b or c has occurred because the level of the RFF SCR is unchanged and there are no surplus assets.

It is therefore possible to have a change in risk profile in respect of RFF business in isolation, non-RFF business in isolation or both together that may result in a change in legal entity coverage ratio that is below the PRA’s indicative view that a material change in risk profile would result in a movement of 5 percentage points or more, even though when considering the business separately, as most firms do for the purpose of risk management, the change in coverage ratio exceeds 5 percentage points. The working party view is that the legal entity solvency coverage ratio for the purpose of calculating the impact of a TMTP recalculation may require adjustment where RFF restrictions exist. Such an adjustment would likely need to be discussed and agreed with the PRA.

Can firms have triggers in their policies different to the 50 bps and 5% cover ratio in SS6/16?

The PRA expects firms to develop their own policy setting out “how the design and calibration of the triggers are related to the firm’s risk profile.” The SS also requires firms when they are making an application for approval to recalculate to consider the PRA’s indicative view of a material change in risk profile (i.e. a sustained change of 50 bps and 5% movement in coverage ratio). However, the SS also states, in the context of the cover ratio, that “the degree of change that is considered material will depend on individual firms’ risk profiles.” As a result, the SS leaves it open to firms to justify a higher or lower threshold based on their own firms’ sensitivities. This includes demonstrating that the chosen threshold would not prevent a reduction in the TMTP when circumstances imply reduced need for the TMTP, i.e. that triggers are symmetrical.

If PRA invite a recalculation should it be compulsory?

SS6/16 refers to the PRA inviting firms to recalculate the TMTP where external market-wide events lead to a change in market conditions that would be likely to cause a material change in firms’ risk profiles. However, firms are required to justify that the market-wide event had a material impact on their own risk profiles in order to carry out recalculation. It is recognised that events could affect firms differently, having material impacts on some firms and little impact for others. It follows that recalculation should not be compulsory and would instead depend on how a particular event affected different firms. Firms could though be expected to justify why recalculation was not appropriate, for example, because it was not in line with the policy or because, based on recent sensitivities, a particular event would not have a material impact. The working party would hope the overhead of demonstrating why recalculation is not appropriate would be less onerous than seeking approval for a recalculation. Notwithstanding this point, the recalculation estimate produced to support a recalculation or non-recalculation should be equivalently robust.

Firms are expected to have symmetric triggers for recalculation. They would, therefore, be expected to show non-recalculation was in line with a symmetric policy and not, for example, influenced by the likely direction of change on recalculation.

4.3. Firm’s Recalculation Policy

Overview

Firms are required to develop an internal policy on the recalculation of the TMTP and agree this policy with their PRA supervisor. This policy should also be approved via an appropriate level of internal governance, for example, be approved by the Audit Committee or Board. A clear and well prepared policy that has been agreed by the PRA will be of benefit to a firm, as this is likely to increase the likelihood and improve the timeliness of approval, whenever recalculation applications are made. It also means that the policy can be confidently reflected in a firm’s strategy/dividend planning and ALM approach.

A TMTP policy could benefit from a clear upfront articulation of the purpose and objectives of recalculation to provide greater understanding of the firm’s rationale for the chosen recalculation approach and triggers and what these are designed to achieve. Use of some examples of circumstances that would and would not lead to a recalculation may help to give greater clarity on how the TMTP would be managed in volatile markets.

Content

The working party’s suggested content of a firm’s TMTP recalculation policy covers the following eleven areas:

∙ Coverage

∙ Circumstances for recalculation

∙ Recalculation triggers and monitoring

∙ Recalculation method

∙ Timelines and governance

∙ Run-off method

∙ Regular review of the policy

∙ Internal consistency

∙ Disclosures

∙ Voluntary reductions

∙ Compliance with regulations and Supervisory Statements

These are outlined in more detail below.

a. Coverage

The policy should clearly state which legal entities within the wider Group the policy relates to, and what the relationship(s) between companies covered by the policy are. Where principles, methods or triggers differ between entities covered by the same policy, these differences should be clearly delineated.

Where a firm has ring-fenced fund(s) and allocates a TMTP to one or more of these ring-fenced funds, the policy should state which ring-fenced funds the policy relates to and the relationship(s) between the ring-fenced funds and the remaining part of the fund, or between different ring-fenced funds.

b. Circumstances for recalculation

The policy should clearly state the circumstances likely to result in a recalculation. The list should aim to be exhaustive although in practice this may be difficult to achieve and firms should ensure that their policy is sufficiently flexible, while still remaining appropriate and fit for purpose, should such an event occur. Whether the crystallisation of one or more these events would result in a recalculation of the TMTP will depend on its materiality.

Circumstances for a recalculation will cover both changes in operating conditions and other, more structural, changes in the composition of pre-1 January 2016 business.

c. Recalculation triggers and monitoring

The policy should clearly define the materiality triggers that, if met, would result in an application to recalculate the TMTP. The triggers may vary from firm to firm and will depend on each firm’s own risk profile and, to a certain degree, risk appetite. They will, of course, have to consider those described in the PRA’s Supervisory Statement SS6/16. Triggers could be based on the movement in solvency coverage only in relation to components of the TMTP (e.g. exclude dividend payments) with potentially more sophisticated rules around timing of recalculation being developed.

At a practical level, a firm needs be able to be monitor its position against the triggers and this consideration should be factored into the policy. Monitoring can be either input (e.g. frequency of event) or output (e.g. post-recalculation change in pro-forma solvency ratio) driven or a combination of the two. However, the monitoring needs to be sufficiently robust so that applications can be made when they are actually required (i.e. when the criteria outlined in the PRA’s Supervisory Statement SS6/16 are met).

The policy should also state whether triggers are in relation to standalone events only or whether they could also relate to the accumulation of a number of smaller events. If the latter is deemed to be a reasonable approach for the firm, then the policy should consider how it would treat the accumulation of changes in operating conditions (e.g. interest rate changes) and structural events (e.g. a Part VII transfer or a sale/purchase of business). The former may well not pass the other PRA’s materiality tests outlined in 4.2.2. And so if the market change is not a sustained change then it is possible that a firm applying to recalculate its TMTP in such a scenario (in conjunction with (a) structural change(s)) may find that its materiality triggers are no longer being met by the time approval to recalculate is received, if market levels revert in the prevailing period. While approval to recalculate is likely to be at a valuation date in the past, careful consideration will have to be given as to whether to implement the recalculation in such a situation.

A firm’s policy should also consider how the TMTP should be adjusted over and above linear run-off between recalculations within internal and external solvency reporting. Here a firm may wish to periodically estimate (e.g. quarterly) the true underlying value of the TMTP and possibly allow for the underlying value of the TMTP within its Management Information and solvency disclosures, where possible. Although, for solvency disclosures it is worth noting that the TMTP cannot be increased above the level last approved by the Audit Committee, in theory it is possible to decrease the TMTP in solvency disclosures. This asymmetry is not necessarily required for internal reporting purposes, but it may be helpful to align to the external reporting approach to avoid confusion. Whatever approach is taken here, it must be clearly communicated to the end users of the information.

How the TMTP will be monitored against the recalculation triggers for a material change in operating conditions should be described in the policy. An efficient approach would be to re-use or extend existing solvency monitoring processes. The policy should also consider for how long a trigger must be breached before an application to recalculate the TMTP is made to the regulator; in particular, the SS refers to changes in interest rates being sustained. The policy will therefore need to state what constitutes the firm’s view of a sustained change in interest rates. It could be inferred that the PRA’s view of a sustained change is a trend over 6 months. It is likely that sustainability is a particular focus of the PRA to ensure that:

(i) a recalculation is not being requested as a result of normal market volatility and

(ii) the frequency of recalculation requests is reduced to allow for practical considerations from a PRA perspective.

The frequency and outcome on the change in solvency ratio and own funds will vary from firm to firm and will reflect a combination of the following:

∙ The magnitude of the TMTP relative to the solvency position of the legal entity.

∙ The sensitivity of business to changes in the trigger, for example the sensitivity of the risk margin to interest rate movements is expected to be greater for a legal entity with mono-line annuity business compared to a legal entity with shorter duration business.

∙ The general prevailing economic conditions and in particular changes in the level of interest rates.

d. Recalculation method

A detailed description of how the recalculation will be performed, including justifications of areas where discretion or proportional approaches have been used, should be included in the policy. Where areas of regulations and supervisory statements are not prescriptive the policy should clearly outline the firm’s interpretation and justify why this interpretation is appropriate.

It should be noted that the recalculation methodology does not necessarily need to be fully contained within the policy; it could be referenced as a separate document. Separation may be helpful from a practical perspective, for example, to reflect different governance paths or frequency of update/review.

The recalculation methodology should also cover how the recalculated TMTP should be allocated across Homogenous Risk Groups.

e. Timelines and governance

A firm’s policy should consider the broad timeline from the point of recalculation trigger being met right through to the point of reflection of the recalculated TMTP in a firm’s solvency reporting templates. This timeline should include the internal governance steps that are required before an application to recalculate is made to the PRA and the turnaround time for the PRA review. It is also important that firms understand the content and time required by the regulator to approve an application, to support efficient balance sheet management. It is therefore beneficial for a firm to have an open and frequent dialogue on TMTP recalculations with their regulator, especially while their recalculation policy is being developed.

It is a requirement for the Board to be content for a recalculation application to be made and that the Audit Committee must sign off the recalculated TMTP following an approval from the PRA to recalculate. These governance points should be reflected in policy and process.

For a recalculation of the TMTP resulting from a change in operating conditions, the policy should state whether the recalculation date will be related to the date that the application is made or as at another date such as the date it will be reflected in a firm’s solvency reporting templates. This point will be guided by dialogue with a firm’s supervisor.

Where a recalculation of the TMTP results from a change in risk profile, not connected to operating conditions (i.e. structural), then the policy should ensure that the recalculated TMTP is only introduced at the same time that the material change in risk profile is made. In practice, this will require regular and timely discussions with the regulator and the TMTP recalculation process will have to be factored into internal governance and implementation timelines. In particular, an application to recalculate should be made with sufficient time for the regulator to provide contingent approval so that the recalculated TMTP can be implemented at the same time as the structural change is made.

f. Run-off method

The approach to run-off should complement the recalculation method, so that the TMTP runs off to zero over its lifetime in a sensible manner. The policy should consider when and how the TMTP is run-off in a firm’s solvency estimates and regulatory disclosures. For example does the TMTP run-off annually and if so should it be run-off on 31 December in line with reporting dates or 1 January in line with regulation. EIOPA released a guidance statement in December 2016 that stated either were permissible for regulatory reporting purposes. However, the guidance stated that if a 1 January date is selected then the firm should ensure that the monetary impact of the run-off on 1 January is disclosed in its annual Solvency II Pillar 3 disclosures, in order to demonstrate a true and fair view of the firm’s disclosures. The EIOPA guidance also stated that it was permissible for a firm to run-off the TMTP more frequently, for example quarterly.

As described in section 5.3.1, there are a number of methods to avoid the “Double Run-off” issue and the policy, if not already reflected in the recalculation methodology, should reflect the firm’s chosen approach.

g. Regular review of the policy

The policy should be regularly reviewed for appropriateness and the policy should state the frequency of these reviews. For example, as the TMTP run-offs to a significantly lower level in the later years of its lifetime, it may be appropriate to adopt a more proportionate approach to recalculation than had previously been taken. The policy may also indicate the circumstances under which the policy may be reviewed outside of its regular review cycle.

h. Internal consistency

The policy should be compatible and consistent with, and complement, its other internal policies and processes, examples of which include: Internal Model change policy; ALM policy; ORSA; Solvency Monitoring; dividend policy, and audit policy.

i. Disclosures

The policy should state when the recalculated TMTP should be reflected in a firm’s private quarterly and public annual regulatory solvency disclosures along with how any associated commentary should be approached. Firms will also disclose solvency results in non-regulatory external disclosures and a firm’s policy may also cover the approach for these disclosures too.

j. Voluntary reductions

While it is relatively clear that increasing the value of TMTP under the current TMTP approvals process would require an application to the PRA, it is less clear whether firms could voluntary reduce the value of TMTP without an approval process. If this was possible, we would envisage the upper bound of the TMTP allowed without PRA approval to be the value lower than the last approved TMTP, less appropriate allowance for run-off.

The working party believes allowing firms and their Audit Committees this discretion would be a beneficial development as it would reduce the potentially awkward disclosure of accounts which are not a fair and true representation of the firm’s financial position in this situation where the proforma TMTP is materially lower than the approved TMTP at the reporting date. This difference could arise because the prevailing conditions for TMTP recalculation have not been met, i.e. the change in operating conditions is not yet deemed to be sustained or the subsequent change in proforma solvency ratio is less than the 5% change outlined in SS6/16, but the Audit Committee or firm’s senior management are uncomfortable with the associated over statement of the TMTP value in the accounts.

The working party believes if the changes in operating conditions are temporary and are not sustained then the firm can increase its TMTP back up to value which is limited to the approved upper bound. If changes in operating conditions are then deemed to be sustained the TMTP application process can then be commenced.

The working party believes if this approach is considered by firms it should be outlined in the firm’s recalculation policy and discussed with its regulatory supervisor in advance.

k. Compliance with regulations and Supervisory Statements

The policy should clearly explain how it complies with the relevant TMTP regulations and Supervisory Statement. It may be helpful to include an appendix that cross refers the policy to the regulations and Supervisory Statement to achieve this.

4.4. Application Process

Does having a policy in place and agreed with the PRA mean approval of recalculations can be light touch?

SS6/16 does not talk about the approval process but does indicate that the PRA would consider recalculations on case by case basis, i.e. separately for each firm.

While it is clearly appropriate that the PRA can give whatever degree of consideration is appropriate to the circumstances, both the PRA and firms would benefit from a structured and orderly approval process. It would presumably be for firms to discuss such process with the PRA and for firms’ policies to include agreed process. Further, if triggers were agreed with the PRA in advance then a mechanical process could follow, with the PRA being forewarned on the breach of a recalculation trigger and the result used in reporting pending any review the PRA thought necessary. That said, it is important to note that the recalculation of the TMTP is not dynamic and an application will be required.

It is possible that some circumstances not envisaged in the policy could occur which would nevertheless justify recalculation. Such cases would be less routine than recalculations from agreed triggers and so could need closer review. Firms would though want to discuss such cases with the PRA at an early stage.

What is the content of an application?

As noted above SS6/16 does not detail the application process and so the requirements would need to be discussed with the firm’s supervisor. However, the PRA do state on their website that the application should contain:

(i) A Solvency II approval application form, which is available on the PRA’s website;

(ii) An internal document setting out thresholds and triggers for any material change in risk profile – this should reflect a firm’s own risk profile and not solely look at external factors;

(iii) An explanation as to why the firm believes there has been a material change in its risk profile, or will be a material change in the risk profile in the event of a future transaction that is reasonably likely to happen;

(iv) A copy of the firm’s policy for the recalculation of the TMTP; and

(v) An agreement from the Board that it is content for the application to proceed.

The firm may also want to include the following in the application:

(i) The proposed date of recalculation;

(ii) The firm’s recalculation methodology, or confirmation that there have been no changes to the methodology previously submitted. The methodology must also demonstrate how the FRR comparison test continues to be met at the recalculation date;

(iii) Evidence of how the change in risk profile has been reflected in other related processes such as ORSA and Model Change (where applicable);

(iv) An updated Phasing-in Plan or confirmation that the previous Plan remains viable (where applicable); and

(v) Any other relevant information that may help support a successful application.

5. How to Recalculate the TMTP?

There does not seem to be consensus around a “one-size fits all” approach to recalculation. Instead, firms are developing different approaches to tackle the technical and practical challenges of recalculation, with the methods used involving varying degrees of complexity.

In this respect, it is worth reminding ourselves of the purpose of the transitional measures. The transitional measures in Solvency II are intended to ensure a smooth transition towards the full requirements of the new regime. The measures aim to avoid market disruption potentially associated with the move to a new regulatory regime and to limit interference with the existing availability of insurance products.

With that being the purpose of the TMTP, theoretical correctness does not necessarily outweigh doing what is practical to achieve a smooth transition in line with the Solvency II rules.

5.1. Introduction

Firms have to decide how they will recalculate the TMTP. Recalculation will be required at least every 2 years, on a material change of risk profile, and at other times would help demonstrate whether a recalculation trigger has or has not been reached.

Ultimately, there is a balance to strike between alignment with others in the market, responsiveness, and practicality. When considering how to recalculate the TMTP the working party has considered five overarching themes. The themes were presented in the table below from section 2.3.

The next few sections provide a number of suggestions which firms may wish to utilise in their TMTP recalculation. These suggestions have been split into:

∙ the above key themes (section 5.2),

∙ issues which impact the calculation of the unrestricted TMTP (section 5.3), and

∙ additional issues that impact the derivation of the FRR comparison test (section 5.4).

It should be noted that the suggestions may not be appropriate for all firms. Ultimately a firm’s recalculation approach will need to consider its own particular circumstances, be agreed internally within the firm and discussed with the PRA.

5.2. How to Recalculate TMTP – Key Themes

5.2.1. Segregation of business

Recalculation of the TMTP requires firms to segregate Solvency I and Solvency II technical provisions into the parts in respect of pre- and post-1 January 2016 business. This is because the TMTP only applies to business written before Solvency II came into force. Further, and depending on interpretation of the FRR limitation, capital requirements and non-technical provisions may need to be split between the two business classes. Such segregation is likely to need reporting systems to be updated to be able to identify the classes and to report them separately. Where underlying assets affect the calculations, for example for with-profits business and annuities with a Matching Adjustment applied, an additional level of asset hypothecation may be indicated.

This provides both a calculation granularity challenge, as well as the challenge of being able to reconcile and explain reported results for pre- and post-1 January 2016 business.

Issues relating to this segregation are outlined in more detail in section 5.3.2 for the unrestricted TMTP and section 5.4.5 for the restriction of the TMTP.

5.2.2. Maintaining the prior regime

Recalculation of the TMTP requires firms to maintain aspects of models and methodology from the previous solvency regime. The working party expects the full maintenance of Solvency I models, methodology and associated governance, in combination with the enhancement of granularity for pre-1 January 2016 business, would be excessively onerous for most firms to implement.

The working party therefore expects a TMTP recalculation will need simplified, and proportionate, methodologies. Proportionality is expanded upon further below.

5.2.3. Proportionality

The PRA supervisory statement on a TMTP recalculation (SS 6/16) implies that proportionate approaches may be acceptable, indicating that firms should discuss proposed methodology with their supervisors. This is helpful and leaves it open for firms to agree with the PRA what would be proportionate for their own circumstances. What would be proportionate is difficult to define and will vary from firm to firm and legal entity to legal entity. A view on proportionality is ultimately an area of judgement which needs to be agreed internally within a firm and, as outlined in SS6/16, discussed with the PRA.

One potential way to consider proportionality is as follows.

Each of these is expanded upon below.

Recalculate or not?

A firm should define areas of recalculation which will be theoretically maintained going forward, and define those areas of recalculation which it believes on grounds of principle should not be maintained.

An example of an area of recalculation which might not be maintained, on the grounds of principle, is the maintenance of separate asset hypothecations for Solvency I and Solvency II technical provisions.

Maintaining a separate (theoretical) asset hypothecation based on what investment strategies might have been had Solvency I continued seems a step too far, and likely to be difficult to achieve in practice. However, using the asset allocation adopted under Solvency II to determine Solvency I technical provisions for recalculation is likely to lead to an erosion of the TMTP value because firms will not be purchasing assets to optimise their Solvency I technical provisions.

Where such erosion was significant, firms could presumably propose simplified methods to allow for Solvency I asset allocations in recalculation. For example, a firm may assume the asset allocation in force at 31 December 2015 applies to TMTP recalculations going forward.

Materiality framework

A firm should agree a materiality framework to apply to those areas of recalculation, which will be maintained going forward. Firms could define the recalculation materiality relative to its general materiality and risk appetite frameworks.

“Exact” calculation

A firm should define what it believes an “exact” calculation is. We use the terminology “exact” here to note that modelling in general is a simplified representation of the real world.

The working party expects a typical definition of “exact” as being the maintenance of the methodology and processes which applied at 1 January 2016. Notwithstanding this point, it is possible some firms may develop processes and methodologies after 1 January 2016, which provide a more precise value of the TMTP than those which applied at 1 January 2016.

Understanding onerous

As part of defining an “exact” calculation, firms should understand which parts of recalculation would be onerous to carry out exactly. If the “exact” calculation is not onerous then additional simplifications will not be required.

Propose initial simplification(s)

Firms will propose an initial simplification or simplifications on onerous parts of recalculation, justifying them relative to the “exact” calculation.

Understand limitations

Understand the limitations of the simplification, i.e. in what circumstances the simplification would fall outside of the firm’s TMTP materiality framework.

Part of understanding limitations of simplifications may include the use of qualitative and quantitative methods. For example, a firm may use qualitative methods to outline theoretical analysis to outline when a recalculation may fall outside of the materiality limit, and use sensitivity analysis to provide an expectation of this occurring.

Amend proposal if required

If the limitations are deemed to be too material, then the proposal(s) should be amended and assessed again.

5.2.4. Firm specific

Recalculation methodology will depend on the following factors:

Materiality of the TMTP

A TMTP which is material relative to the capital surplus (i.e. the surplus of capital resources over capital requirements) is likely to require a more complicated, more robust and more frequent recalculation than a TMTP which is less material relatively to the capital surplus.

The type and complexity of the underlying business

The recalculation methodology is likely to depend on the type and complexity of the underlying business written in the legal entity, or ring-fenced fund. For example a mono-line writer of business, e.g. annuity business, may be able to employ more accurate recalculation methods than a multi-line insurer.

Furthermore certain types of business may be easier to derive a TMTP in certain aspects than others. For example, it may be easier to split annuity policy data than unit-linked policy data.

Whether the legal entity, or ring-fenced fund, is open or closed to new business post-1 January 2016

A TMTP recalculation for a legal entity, or ring-fenced fund, which was closed to new business prior to 1 January 2016 is significantly simpler than for a legal entity, or ring-fenced fund, which is still open to new business. The requirement to segregate business written pre- and post-1 January 2016 is trivially met by there being no post-1 January 2016 business.

Similarly, where a legal entity or ring-fenced fund writes only immaterial volumes of new business post-1 January 2016 it may be reasonable to simplify the recalculation of its TMTP by ignoring the impact of post-1 January 2016 business.

Whether a TMTP is restricted by or close to the FRR comparison

Where a legal entity, or ring-fenced fund, has a TMTP that is based on, or close to, the FRR comparison test, the calculation will require a more robust derivation of the FRR comparison test components than for a firm whose FRR comparison test is less likely to “bite.”

Notwithstanding this, all firms seeking a recalculation are expected to provide details of the FRR comparison in their applications for recalculation or justify why the test would not restrict the TMTP.

Which of the two Solvency I Pillars is relevant for the FRR comparison test

The recalculation of the TMTP will depend on which of the Solvency I Pillars is the more onerous for a legal entity, or ring-fenced fund. Where one of the Solvency I Pillars dominates and this can be expected to continue going forwards it may be justifiable to exclude the other Solvency I Pillar from the calculation. This simplification is explored in more detail in section 5.4.6 and would clearly need to be discussed with the PRA.

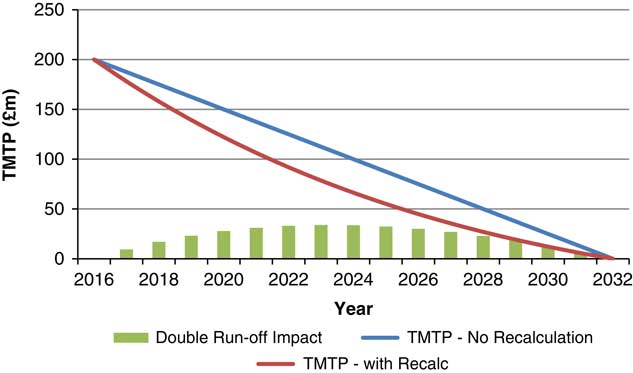

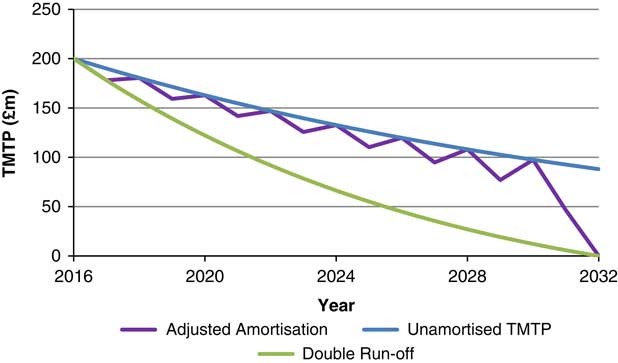

Reporting systems and process constraints