1. Introduction

Investing is an activity in which consumption today is foregone in an attempt to allow greater consumption at a later date. ‘Risk’ is the possibility that this objective won’t be attained.

Warren E. BuffettFootnote 1 , February 2018The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries’ Risk measures working party was initiated with the following Terms of Reference:

to inform discussion of the usefulness of alternative approaches to risk measurement for long-term liability constrained investments, with particular attention as to whether investment strategies might be skewed away from growth assets, to the detriment of long-term gain for customers and may actually increase their risk.

to increase awareness of the possible influence exerted by the use of short term – viz. banking based – risk assessment approaches and their impact on asset allocations in the real economy.

1.1 What risks have been considered?

Investment risk: The possibility that changes in the values of, or income from, assets cause a long-term investor to fail to achieve its goals over its investment horizon.

The categories of long-term investor covered will include those which have liabilities based on some demographic factors and some form of real value or inflation-based guarantees, i.e. a pension fund or insurer with long-term liabilities. Although the background context of industry practices and regulatory aspects originates from a UK perspective, the economic principles are globally applicable.

The focus is on the investor’s long-term investment strategy achieving an optimal economic risk/return payoff, and the numerous challenges in managing stakeholder perceptions, behaviours and actions.

1.2 Research background

The theme of long-term investing is at the core of actuarial science, from its traditional roots in life insurance and pensions, to the present day. In recent years, the advent of the risk-based and market consistent approach of, inter alia, Solvency II (‘SII’) for EEA insurers has emphasised the short horizon over the longer horizon. This paper seeks to consider the appropriateness or otherwise of this short-term-based thinking by taking a fresh look at the fundamental economics underlying long-term investing for insurance and pensions, and some of the constraints and barriers to the practical implementation of ‘alternative’ approaches.

In 2014, the seminal discussion paper Pro-cyclicality and structural trends in investment allocation by insurance companies and pension funds was published by the Bank of England and the Pro-cyclicality Working Group, a joint venture between the IFoA and the Bank of England. This paper looked at the policy issues arising from the trend to short-term investment behaviour by pension funds and life companies, lower equity holdings reflecting reduced willingness to take on risk, and pro-cyclical investing that exacerbates market cycles. All of these factors threaten the security of retirement income and the availability of finance for investment in industry and infrastructure.

The IFoA had a successful seminar on the subject in September 2015 (Expert Panel Pension Funds and Life Companies: Are they Fit for Purpose?) which led to potential areas for future research.

The key issues identified were

marked decline in the willingness of pension funds and insurance companies to take on investment risk, with much lower equity holdings in recent years

significant herding in the way that UK defined benefit pension schemes have been investing

a short-term agenda driven by regulation such as the SII framework

the need for a better understanding of risk; market risk versus investment risk

simpler, more focused institutions that address the structure of the industry and incentives for behaviours

Further details can be viewed on the webpage https://www.actuaries.org.uk/news-and-insights/media-centre/media-releases-and-statements/what-procyclicality.

1.3 The role of long-term investing

In the twenty-first century, the accelerating pace of change seems to create unstoppable pressures for ever-faster processes and transactions. Time horizons for the deployment of cash in securities have shortened. Where silicon has replaced carbon on the trading floors, algorithms trade in a matter of microseconds, and is getting close to the limits of what is possible with known physics (light travels about one foot per nanosecond).

Conversely, creating real economic wealth requires a capital base which is available over sufficient time and depends on an effective allocation of resources, including efficient availability of finance for investment in industry and infrastructure. Since long-term investors comprise the world’s largest asset owners (details in Section 4.1.1), they exert a major impact on the global economy.

1.4 Scope

In this paper we consider the following key areas:

Long-term versus short-term investors/investing

Dimensions of risk: Investment risk versus market risk

Investors and their economic risk capacity

Components of, and approaches to, the measurement of risk

In particular

Section 2 outlines the methodology we have adopted in producing this paper.

Section 3 outlines the findings of our literature review.

In Section 4:

We define the scope of which investors we are considering – as the universe is wide.

For those chosen, we consider what their fundamental economic risks are – by separately considering the investors and their needs and how the universe of available investments meets these needs.

Section 5 considers alternative risk measurement approaches:

Starting with the various aspects that are taken into account in all risk measurement approaches.

Commenting briefly on the use and impact of discounting.

Starting from first principles on how risk measures should be set with reference to the liabilities being provided (i.e. Time horizons of the cash flows or economic asset-liability modelling).

Then considering some different risk measurement approaches (both those currently used and alternative approaches) and how appropriate these are to the risks outlined in Section 4.

1.5 Necessary limitations of coverage

Any paper on the practical aspects of investment risk management can only cover a limited number of selected topics. While acknowledging the reality of the numerous other aspects of the social, political, legal/regulatory, technological, economic and business environment, this paper is not intended to explicitly discuss in any depth details of regulations, pensions funding, considerations such as sponsor covenants and the role of the Pension Protection Fund, UK (‘PPF’), specific details of life insurance/pensions product types, fixed income risk and the impacts of recent monetary policy viz. quantitative easing, pro-cyclicality, herding, macroeconomic risk and systemic risk, the use of hedging strategies and derivative instruments.

More specialist investment topics such as passive versus active investing, growth styles versus value styles, public versus private funding sources, factor investing, algorithmic approaches versus sector and stock selection, details of newer ‘alternative’ investments, and so on are also unfortunately beyond the scope of this paper.

Although the geographical focus of the sections on industry practices and regulatory aspects is on the UK (and not from around the globe), the concepts and principles of long-term investing and shortfall risk are universally applicable to all classes of global long-term investors including individual investors.

2. Methodology

After considering the identified policy issues arising from the trend to short-term investment, the authors decided to first address the need for a better understanding of risk, in particular market risk versus investment risk.

It was considered best to start afresh with the basic fundamental economics, the underlying purposes of long-term investing, what makes financial sense and would most likely be optimal for the ultimate investor, rather than automatically assuming that the recently overarchingly dominant (at least in the UK insurance world) regulatory and accounting rules and conventions were the best approach for business management.

The authors decided to take a practical view rather than focus on theory.

This paper is not intended to be a comprehensive regulatory critique of the Solvency II standard formula Solvency Capital Requirement (‘SCR’) mark to market (‘MTM’) (and equivalents in the pensions domain), but is instead intended to be a broader consideration of risk measurement approaches across different businesses.

The authors present ‘alternative’ perspectives which they consider relevant, some of which were more prominent in actuarial thinking in the past but that have in recent years, in the immediate aftermath of the 2007–2009 global financial crisis trauma, become submerged or been repressed in the wider environment. They deliberately chose to consider perspectives both from across the actuarial profession and independent wider sources.

The objective is not to provide a formulaic ‘full and definitive alternative’ model in all its details or to ‘prove’ anything mathematically, but rather to look at alternative perspectives and approaches in view of overall tendencies and trends, perhaps providing an interpretation that sheds some more light on the many dimensions of investment risk. The authors suggest that a multifaceted view of the future is better than sole allegiance to one enforced paradigm.

3. Literature review

The authors considered and reviewed a range of literature on long-term risk measurement approaches, including historical and more recent work done by, inter alia, the Bank of England, the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, and the International Monetary Fund (‘IMF’). The actuarial literature review was focused on UK insurance and UK defined benefits pension schemes and ‘financial economics’ (‘FE’) papers.

In addition to printed/electronic literature, materials were assimilated from attendance at public and non-public events, audio/video materials on the Internet, and discussions with a range of knowledgeable and experienced individuals.

3.1 Life insurance

Life actuarial valuation principles have evolved significantly since the 1950s with many published papers on this topic. Historic papers between c.1950s to 1985 on this topic by Haynes & Kirton, Redington and Skerman focused on principles of matching assets to liabilities, as well as considerations for liabilities to be valued in a consistent manner. Skerman also noted in his paper that he felt ‘market values, particularly for equity shares, are too volatile for the purpose of steering the finances of an insurer over the long term because they vary with the market’s assessment of future prospects as regards earnings and dividends for equity shares and as regards rents for property.’

The papers above prior to 1985 pre-dates the application of market consistent valuation approaches, which have grown in favour with insurers for more than a decade. A more recent paper by Kamran Foroughi on this topic (Reference Foroughi2012), Market-consistent valuations and Solvency II: Implications of the recent financial crisis enables the reader to understand the implications for insurers from the use of this approach with a focus on the impact it has on investment decisions.

Foroughi raised in his paper a macroeconomic concern that market-consistent frameworks could lead to pro-cyclicality where falling market values could threaten insurers’ solvency and drive insurers to sell higher risk assets to fund purchases of lower risk assets. Potential ways in which this might be mitigated span:

1) decisions based on multiple metrics and not solely on market-consistent valuations;

2) recognition that the efficient market hypothesis may not hold in financial crises;

3) introduction of flexibility in the regulatory regime at times of financial crisis; and

4) stakeholders ensuring capital requirements during benign periods are sufficient to meet losses during crises.

In 2016-2017, work done by the UK Treasury Select Committee and the numerous contributors to this enquiry raised core questions concerning the impact on ultimate customers of the new EU SII regulations. It was recognised that whilst it would be good for the UK to maintain equivalence with the rest of the EU, there is a risk that standardisation does not work equally for all companies and introduces competitive advantages for some and disadvantages for others. This leads to a cost to the industry and could increase prices for consumers.

The impacts of other considerations such as regulation and accounting are described in Section 4.7, and fuller documentation of all the above-mentioned topics is in Appendix 1.

3.2 General insurers

As General Insurers’ liabilities are relatively short tailed, the time horizons over which General Insurers invest to meet their liabilities are generally too short for consideration in this paper. However, for some insurers, the increasing prevalence of Periodical Payment Orders (‘PPOs’) is shifting the liability, and hence investment, horizon.

PPOs provide personal injury claimants with a continuing series of regular payments to meet their care needs – rather than a single lump sum. PPOs are normally awarded to younger and/or larger claims and can be imposed by the Court if it believes that this is in the best interest of the injured person.

As PPOs were only introduced in 2005, literature on PPOs and the impact on investment approaches is generally limited. Indeed, the IFoA’s PPO Working Party is one of the most active contributors in this area – in particular conducting regular qualitative surveys with insurers on their PPO exposure and approach.

In their most recent survey, the PPO Working Party noted that 7 of the 12 insurers surveyed had changed their investment strategy as a result of PPOs, with their main concerns being around the long duration associated with PPO liabilities and the inability to find assets that track the inflation indexation used for PPOs (which is typically the Annual Survey of Household Earnings)Footnote 2 .

3.3 UK defined benefits (‘DB’) pension schemes valuations through ‘financial economics’ (‘FE’) papers

Pension scheme valuations literature was reviewed, covering this subject chronologically from its earlier roots through to the times when ‘financial economics’ became fashionable. In respect of DB pensions, most of the FE papers were found to assume that financial conditions as at a relevant date will continue to hold unchanged forever, with volatility being treated as risk – contributing to deficits.

Owing to practical constraints, little account has been taken of non-UK literature. (The US actuaries embarked on that path some years earlier than UK actuaries.)

Until 1989 (Arthur & Randall), the pensions papers sponsored by IFoA ignored ‘financial economics’. The most relevant older papers are those by Puckridge, Redington (although not about pensions), Heywood & Lander and Day & McKelvey. Those pension papers addressed the concept that current market values were not necessarily relevant for longer-term ongoing funding assessments.

From 1989 onwards, especially by Exley, Mehta & Smith, it was assumed that only current market values could be relevant for longer-term ongoing funding assessments, the opposite end of the spectrum. With the benefit of hindsight, it may be regarded as surprising that the later papers excluded any back-testing exercises to see how such an approach could have worked.

A fuller discussion of these topics is in Appendix 1.

3.4 Highlights

Whilst the full list of references appears in the References section at the end of this paper and more detailed insurance and pensions summaries are in Appendix 1, some important works which are closest to the central themes of this paper are:

– Bank of England and the Pro-cyclicality Working Group (2014), Pro-cyclicality and structural trends in investment allocation by insurance companies and pension funds

This paper inspired the formation of the Risk measures working party and hence this research.

– IMF Working Paper WP/16/38 (Reference Jones2016) by Bradley A. Jones. Institutionalizing Countercyclical Investment: A Framework for Long-term Asset Owners

This paper distinguishes different investor types and, most critically, their contrasting risk features and economic risk management focus.

– Reinventing Financial Regulation: A blueprint for overcoming systemic risk (Reference Persaud2015) by Avinash Persaud

This book comprises ‘an analysis of the fundamental flaws that plague the current system of financial regulation, one built around the ideas of “risk-sensitivity” and “capital adequacy”.’ It is strongly critical of the financial accounting, credit and risk standards which create risk by forcing market participants to act in response to MTM valuation conventions rather than an actual need for readily available cash.

– Focusing Capital on the Long Term (FCLT) (2015), Reorienting portfolio strategies and investment management to focus capital on the long term

This paper discusses the perils of short-termism and develops ideas for some alternative investment strategies to remedy this problem.

– Market-consistent valuations and Solvency II: Implications of the recent financial crisis (Reference Foroughi2012) by Kamran Foroughi

This paper is described above under UK life Insurance. Inter alia, it highlights ways in which some of the undesirable impacts of market consistent valuation approaches for long-term insurers might be mitigated.

– The materials submitted in 2016 – 2017 to the UK Treasury Select Committee enquiry into The Solvency II Directive and its impact on the UK Insurance Industry

These documents address critical concepts and economic principles relevant to long-term insurance investment. Key ideas from them are summarised in Appendix 1.

4. Understanding investment risk

There is a wide universe of investors, each with different objectives and constraints. To properly understand the underlying economics and concepts of this paper, it is worth considering the very basics first. This section discusses:

which investors are the focus of this paper;

the fundamentals of ‘investment risk’ in terms of how it is defined and what it might cover (and how it is referred to throughout this paper);

how investment risk does, and should, influence risk measurement approaches; and

how these factors apply in the real world for investors with different liabilities and constraints.

4.1 Long-term investors

The focus of this paper is on long-term investors. The notion of ‘long term’ will vary across investors. Some cycles, such as economic, business, investment, or valuation cycles, do provide a rough indication of the minimum time frame which might be considered as long. For this paper, the authors have not sought to be too precise on the definition of long term, so perhaps institutions investing for periods over 15 years could be considered the starting point.

We can probably more clearly identify the short-term investors who are not within scope. In particular we do not focus on those investors who focus primarily on instantaneous market values and volatility and for which crashes in such values would result in irrecoverable losses or crystallisation of risk events.

Investment horizon is the total length of time that an investor expects to hold a portfolio.Footnote 3 Classical actuarial thought suggests that this should be based on the nature of the liabilities. For example, a pension fund might be expected to meet most of its liabilities in the next 20-30 years but still needs to meet liability cash flows covering say 75 years, until the last pension beneficiary dies.

The investment horizon is a key factor in determining the investor’s cash flow needs, and hence capacity to absorb short-term volatility risk. Establishing an appropriate investment horizon should be one of the first steps to creating a portfolio.

As investment horizons increase in length, equities are likely to represent a higher risk-adjusted return than fixed-income securities and cash. This is described in more detail in Section 4.3.

4.1.1 Which investors have we considered?

The world’s largest asset owners include pension funds (AUM $41.4 trillion at end of 2017)Footnote 4 and insurance firms (AUM $23 trillion in 2015)Footnote 5 .

Long-term investors also include sovereign wealth funds, endowments and foundations, Venture Capital/Private Equity funds, mutual funds, corporations, and high net worth individuals, but for the purposes of this paper, the subset of investors considered will span insurers with long-term liabilities and mostly private sector defined benefits pension funds. Although the discussion following (with respect to industry practices and regulatory aspects) originates mainly from a UK perspective, we believe that most of the economic principles are applicable to these investor classes globally.

In the UK, institutional clients continue to account for the majority (79%) of total assets under management (all asset classes, as at the end of 2017). The largest client group remains UK and overseas pension funds, accounting for 44% of total assets. Assets managed on behalf of insurance represented approximately 15% of all assetsFootnote 6 .

4.2 Investment risk components

Any investor faces a multitude of risks that can be categorised in a multitude of ways. Appendix 2 outlines one possible way of categorising risks and the different risks that different entities might face when investing. The key ones which are covered in this paper are:

Market risk (or systematic risk – market beta)Footnote 7 .

This is the ‘undiversifiable’ risk associated with investing in the market that affects all securities. Typically it is assumed that this risk can be measured by the volatility or standard deviation of market values and/or returns.

To some extent, market risks can be further split – by, for example, interest rate risk, equity price/volatility risk, currency risk and credit risk. Appendix 2 contains an outline of the market risks for a number of key asset classes over different time periods.

Liquidity risk

Trading liquidity risk, i.e. an investor’s ability to trade, is the risk of not being able to buy or sell investments in sufficient quantities or without excessive haircuts as and when desired because marketplace opportunities are limited.

However, for the classes of long-term investor addressed in this paper, funding liquidity is usually the primary risk to consider. Funding liquidity risk refers to an entity’s ability to continue to function as a going concern, i.e. meet both anticipated and unanticipated immediate net cash outflow needs (arising from either the liabilities or the assets), and avoid permanent impairment. For example, the risk of an insurer needing to meet mass surrender values or a small pension fund with little or no new money inflows or alternative funding resources meeting sudden large benefit payment outflow.

Liquidity risk arises from uncertainty regarding the investment horizon or asset holding period, the correlation across the cash flow demands of market participants, and short run constraints on market making capital.

Liquidity management is discussed in section 4.4.

The application of these risks, and the other risk categorises outlined in Appendix 2, affects investors with different liabilities differently. These are discussed further in Section 4.6.

4.3 Defining and understanding Investment shortfall risk

The definition of risk depends on who the investor is and their economic risk capacity. Contrary to customary usage, asset classes or types are not intrinsically ‘safe’ or ‘risky’ – the degree of riskiness depends on who the investor is, the nature of their funding sources, what constraints they face, and for what purposes they are holding the asset. A ‘risk free’ government bond with coupons and redemption proceeds fixed in nominal terms might be extremely risky for an investor seeking to a meet 30-year inflation-linked liability – it is likely that the investment proceeds might not meet the investor’s target.

4.3.1 Structural risk capacity and investment strategy

An entity’s economic risk capacity should not be confused with its risk appetite or mood. The former is the investor’s ability to bear some amount of volatility risk, whilst the latter the investor’s willingness or unwillingness to take that risk. The long-term investor has a natural ability/capacity to bear the shorter term pricing fluctuations, owing to the extended future time period over which it becomes liable to pay out cash. An example of this is illustrated in Table 1, where the CPPIB takes a genuinely long-term view. However, an investor’s ability to take risk not only depends on the economics, in terms of the nature of their liabilities, but also on practical or external considerations, for example, in terms of regulation.

Bearing in mind their risk capacity and appetite, an entity will choose an investment strategy which is consistent with both their strategic risk capacity and their risk appetite at a given point in the cycle.

Table 1. CPPIB case study

This topic of structural risk absorptive capacity is covered in greater detail in PersaudFootnote 8 , in which the author describes how ‘The different requirements of short and long-term funding provide a genuine capacity to price an asset differently,’ and notes that not only does this make economic sense for the long-term investor, but it also mitigates systemic risk since “The right place for a risk is where there is a capacity to absorb that type of risk. One critical advantage of placing risk where it can be best absorbed if it erupts is that it becomes less dependent on its size being measured correctly. Incorrect measurement of risk is at the heart of financial crises… If risks in the financial system are in the wrong place, then no reasonable amount of capital will save the system”. Persaud favours reinventing financial regulatory systems to change the focus away from risk-sensitivity towards measuring sizes of mismatches between market volatility risk taken and the investor’s structural risk absorptive capacity.

4.3.2 The importance of, and defining, investment shortfall risk

Although different types of investor will be faced with the same array of risks, the liabilities faced by a particular investor will heavily influence the appropriateness of different investment approaches. In particular, the liabilities affect:

○ The term of investment (short term versus long term).

○ The need for inflation protection from inflation linked assets (e.g. RPI/CPI)

○ The nature of the liability (including size of reserves, certainty of cash outgo, whether there is any new money from premiums/contributions, treating customers fairly)

The liability structure is thus a core influence on the entity’s risk capacity.

To emphasise the importance of the liabilities to the investment approach, in addition to the different categories of risks faced by investors outlined in Appendix 2, the concept of investment shortfall risk is of critical importance.

As previously stated, for the purposes of this paper investment shortfall risk is understood and defined in terms of economic reality over time: and is defined in Table 2.

Table 2. Definition of investment shortfall risk

4.3.3 Understanding Investment shortfall risk

Different types of investor take different approaches and may therefore warrant the use of different risk measurement approaches. By definition, this paper will not be able to fully address the bespoke needs or goals of any specifically identified business entity but will focus on the most important economic fundamentals which should drive strategy decisions.

For the purposes of this paper, the measure of investment horizon shortfall risk will be the extent to which the actual results achieved fall short of these targeted outcomes. The size of the shortfall risk will depend critically on the extent of the match between investment horizon and funding horizon.

Figure 1 shows the concept of shortfall risk, for a single cashflow at a point in the future.

Figure 1. Shortfall/surplus and the concept of shortfall risk – Cash flow (point in time)

4.3.4 Shortfall risk: a global case illustration

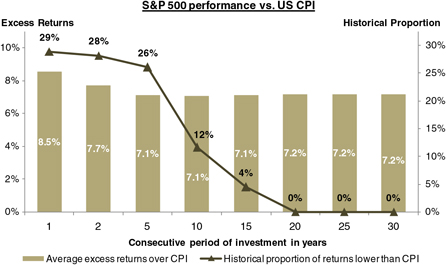

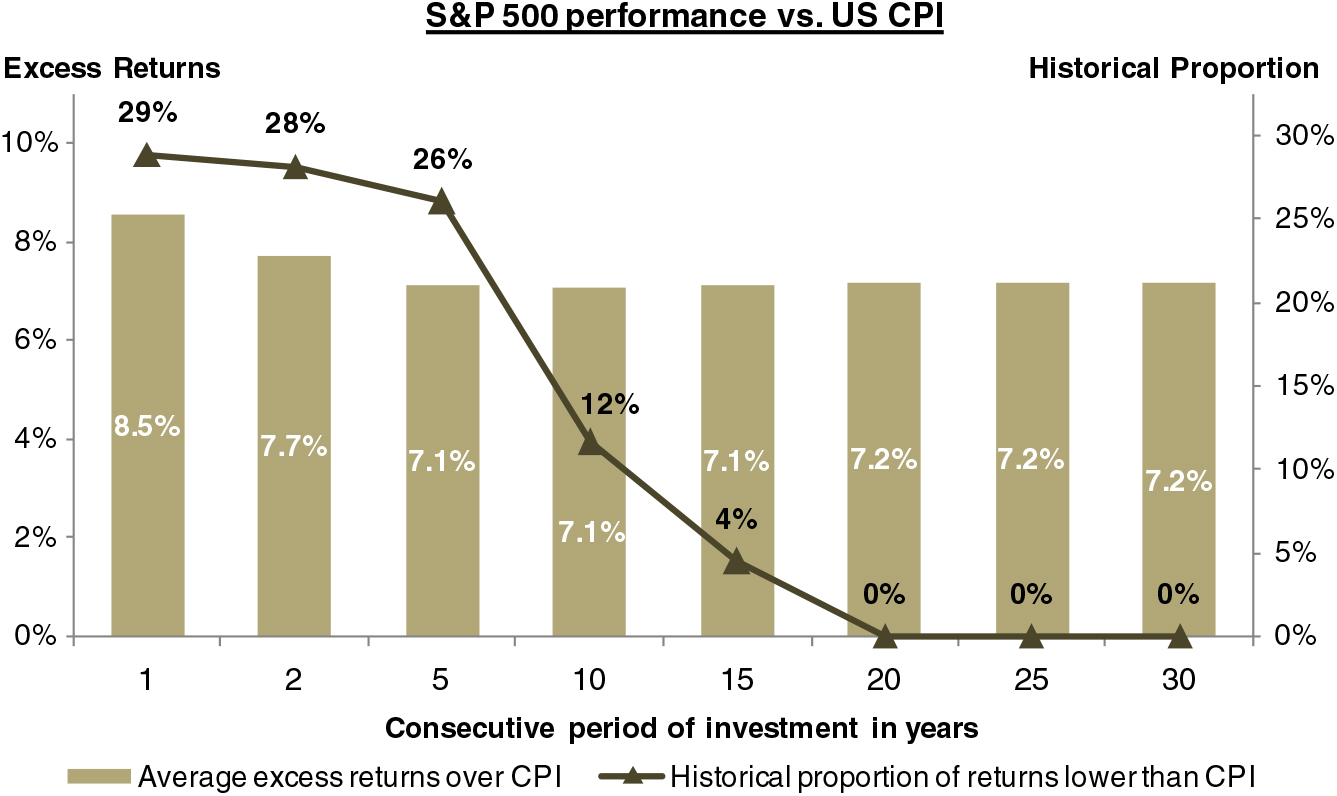

Consider a case where the targeted outcome is investment returns which at least preserve the investor’s purchasing power, i.e. returns in excess of inflation. For this study, a constructed S&P 500 Total Returns index was used as a sample proxy for a well-diversified institutional investment portfolio.

Figure 2 shows a comparison of annual S&P 500 nominal total return performance against US inflation over differing periods of investment, providing the average annual excess returns over annual inflation for varying time periods of investment along with the number of instances of underperformance. This chart uses data for over a century from 1913-2017 and considers overlapping periods of investment.

Figure 2. Chart of real annual returns

The data for these returns charts was sourced from the following:

“Board of Governors of The Federal Reserve System of the United States”; “Bureau of Labor Statistics (“BLS”) of the U.S. Department of Labor”; “Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Research Division – Federal Reserve Economic Data (“FRED”)”; “Multpl.com, S&P 500 dividend yield by month”; “Multpl.com, S&P 500 historical prices by month”; The World Bank, Databank – Global Financial Development”.

Generally, we would expect that shortfall risk is diversified by time and decreases over increasing time horizons. The chart in Figure 2, which is based on actual market data over the past century, appears to support this hypothesis.

Over the past century, nominal annual equity returns have fallen short of the targeted outcome of earning returns in excess of the inflation in at least 25% of the instances for short-term investment of less than 5 years but it steadily declines to less than 5% for investment terms of 15 years or longer.

The returns profile of long-term investment, particularly that of publicly listed equities, is a noisy one, with short-term variability often obscuring and distorting the path of the long-term trend line.

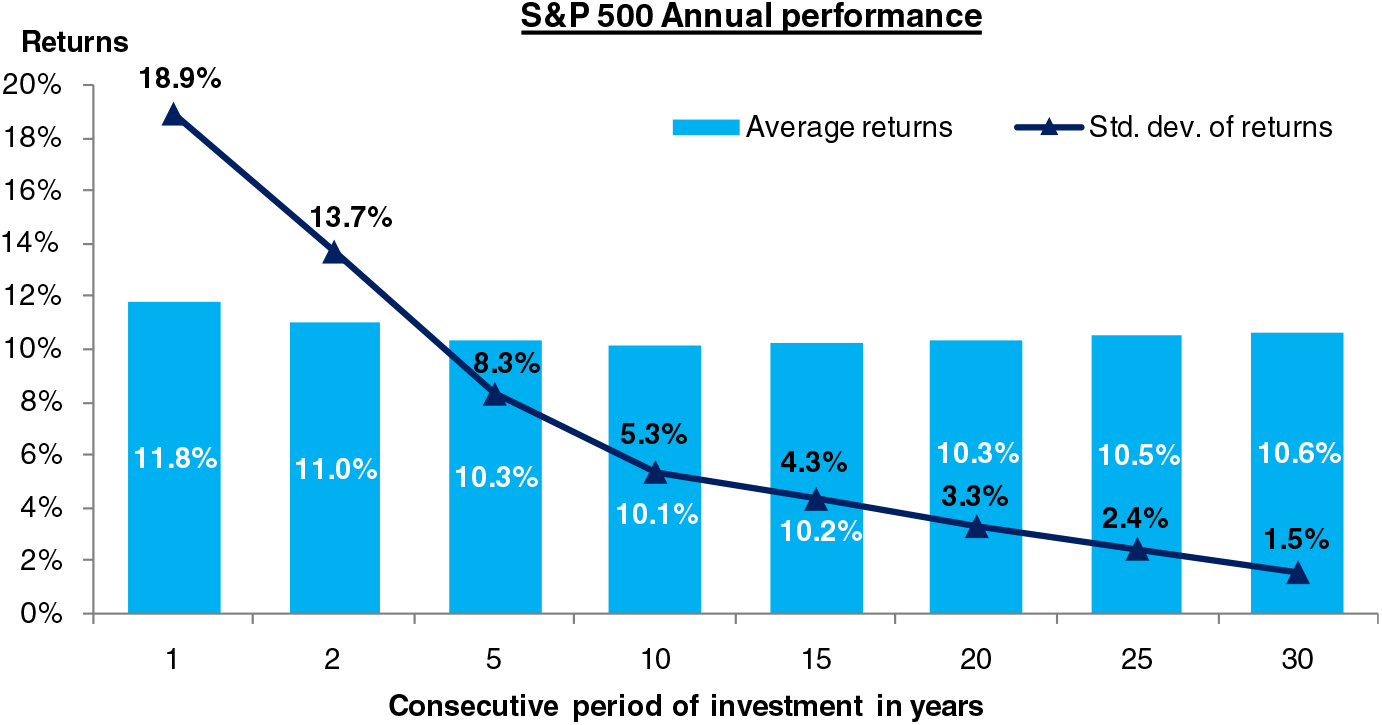

A number of studies have shown that, with increasing time horizon, the long-term trend tends to reach a point beyond which the effects of the short-term trading noise become far less relevant.Footnote 9 This is shown in Figure 3. Asset valuations tend to oscillate over a multi-year horizon around a fundamental value of future cash streams. Further, for assets which are bought and held, the transient capital value fluctuation does not matter as much.

Figure 3. Investment returns over increasing time horizons

This study focuses on review of equity investments especially in the context of a pension scheme with continuous investment inflows requiring sustainable long-term value creation with limited risk of underperformance.

Figure 3 considers the constructed S&P 500 annual Total returns over the past century from 1913 to 2017 for overlapping time period of investment ranging from a year to up to 30 years. This chart shows that returns have been highest over shorter investment horizons before stabilising to marginally above 10% p.a. over longer investment horizons. High volatility (standard deviation in returns) has been experienced over shorter investment horizons but this reduces significantly as the time period of investment increases while the returns are broadly stable around the 10% p.a. mark. These trends appear to imply that equities have provided strong and stable returns over the long term and assist in long-term value creation with relatively low volatility.

Additionally, to more comprehensively assess the risk of underperformance in equities, equity returns were evaluated against alternative low risk investments. In this regard, the constructed equity proxy returns were compared against returns on US 10 year Treasuries for overlapping time periods of investment ranging from a year to up to 30 years during the last century (1913 to 2017). Average annual excess returns over a fixed period of investment along with the number of instances of underperformance with respect to long-term interest rates are shown in Figure 4:

Figure 4. Investment returns of equities versus bonds

The sample equities portfolio has provided higher returns than 10 year Treasury Bond but, historically, the risk of underperformance is large over the short term to the near medium term (five years). Later, the historical proportion of lower equity returns than long-term interest rate reduces significantly and over the far end of the long term (greater than 25 years), reduces to 0%. Thus, historically, these equities have provided approximately 5% p.a. higher returns than the long-term Treasury Bond whenever the period of investment was more than 25 years.

This analysis above examined sample equity performance over the past century including time periods influenced by major economic and geopolitical events like the 1929 Great Depression, the two world wars, and so on. However, past performance may not necessarily provide an indication for the future prediction. (For a fuller description of limitations relating to use of past data, please see the Disclaimer).

4.3.5 Shortfall risk: capturing both sides of the trade off

This feature (the shortfall risk varying by time) drives fundamental differences between different entities – for example, banks versus insurers and pension funds.

The driving principles are well expressed in the IMF Working Paper (Reference Jones2016) which stated that long-term shortfall investment risk could be broken down into

1. The risk of large negative returns causing the fund to lose value, as well as

2. The risk of forgoing large positive returns, thus failing to achieve the targeted long-term return objective.

In other words, shortfall investment risk should be concerned about taking too much and too little risk – i.e. consideration of a risk management approach that takes into account both the left and right tail of the return distribution.

This is in contrast with many market risk management approaches which only focus on the left tail of the return distribution, for example, the use of the value at risk (‘VaR’) measure – which is generally the focus of shorter term investors (referred to as ‘Type 2’ investors in the IMF paper – see Table 3).

Table 3. Distinction of different types of investor. Source: Jones, B.A., (Reference Jones2016). Institutionalizing Countercyclical Investment: A Framework for Long-term Asset Owners, IMF Working Paper WP/16/38

The distinction made in the IMF paper reinforces the points made in this paper; namely that not all investors are ‘Type 2’ investors and the risks faced by longer term investors (‘Type 1’) are of a different nature.

4.4 Liquidity management considerations

For long-term investors, in an economic asset-liability context, the liquidity of both the liabilities and the assets must also be considered. Liabilities can be essentially categorised as negative assets and thus the greater the liquidity of liabilities the more risk it poses to the issuer of the liabilities. For example, a financial entity that takes demand deposits allows depositors to withdraw their balance at will, which presents a high degree of liquidity risk to the entity. On the other hand, in general, pension funds providing to meet the policy benefits at the time of retirement (or death) of the pension beneficiary presents only limited short-term liquidity risk as the requirement is primarily for long(er) term liquidity. Liquidity need is also lower in instances where the liability payoffs are more closely aligned with asset payoffs for e.g. in case of a with-profit life insurance policy with a discretionary bonus, the need for liquidity is further reduced compared to a policy with a non-discretionary bonus .

Whilst in the financial markets in general the term liquidity risk typically covers ‘trading’ or ‘banking’ type liquidity risk of having insufficient short-term deposit funding and marketable assets, for long-term investors the primary concern is the entity’s ability to be resilient to extreme tail loss events, for example, the risk of having to crystallise losses on growth assets to meet unanticipated short-term cash outflow demands. This example describes the concept of funding liquidity for the long-term investor’s liabilities, as contrasted to trading liquidity for the investment instruments held. In the aforementioned example, the funding liquidity of an institution is illustrated to be subject to behavioural risk by individuals, such as in cases where a large number and quantity of insurance policyholders decide to encash their policies just after a market crash.

Whilst more liquidity is needed when conditions are tight, there is an opportunity cost to excess liquidity, typically in the form of lower investment returns. Market makers’ compensation for liquidity provision depends on short-term price reversal. When the volatility (typically indicated by VIX) is high, the intensity of the short-term price reversal effect is stronger, i.e. market makers charge a higher premium for supplying liquidity to the market. Liquidity evaporates quickly during times of extreme market volatility as providers reduce the supply during times of market turmoil demanding higher returns, market volatility tend to increase. Thus volatility and liquidity are closely linked.

It is interesting to note that subjectivity is in fact a necessity for trading liquidity and functional markets. Consider 1000 participants with ‘the same investments, the same market data, the same best-practice, valuation, risk management, and accounting systems and the same prudential controls based on published credit ratings. When one member wants to sell an instrument in response to these systems, so does everyone else. This is an illiquid market. At any one time there will only be buyers or only sellers. Liquidity is about diversity.’Footnote 10 i.e. Subjectivity is in fact needed for the functioning of a healthy financial ecosystem.

4.4.1 Liquidity measures and asset class

Liquidity risk assessment especially for evaluating performance of long-term investment must adopt measures that assess investments taking into account the underlying business risk. Therefore, these measures must:

(i) consider the objectives for the investment and the nature of the liabilities required to be serviced; and

(ii) ensure risks are assessed over a period of time that corresponds with the tenor of risk being held.

The measures that are used to evaluate the liquidity of various assets classes may include evaluation of:

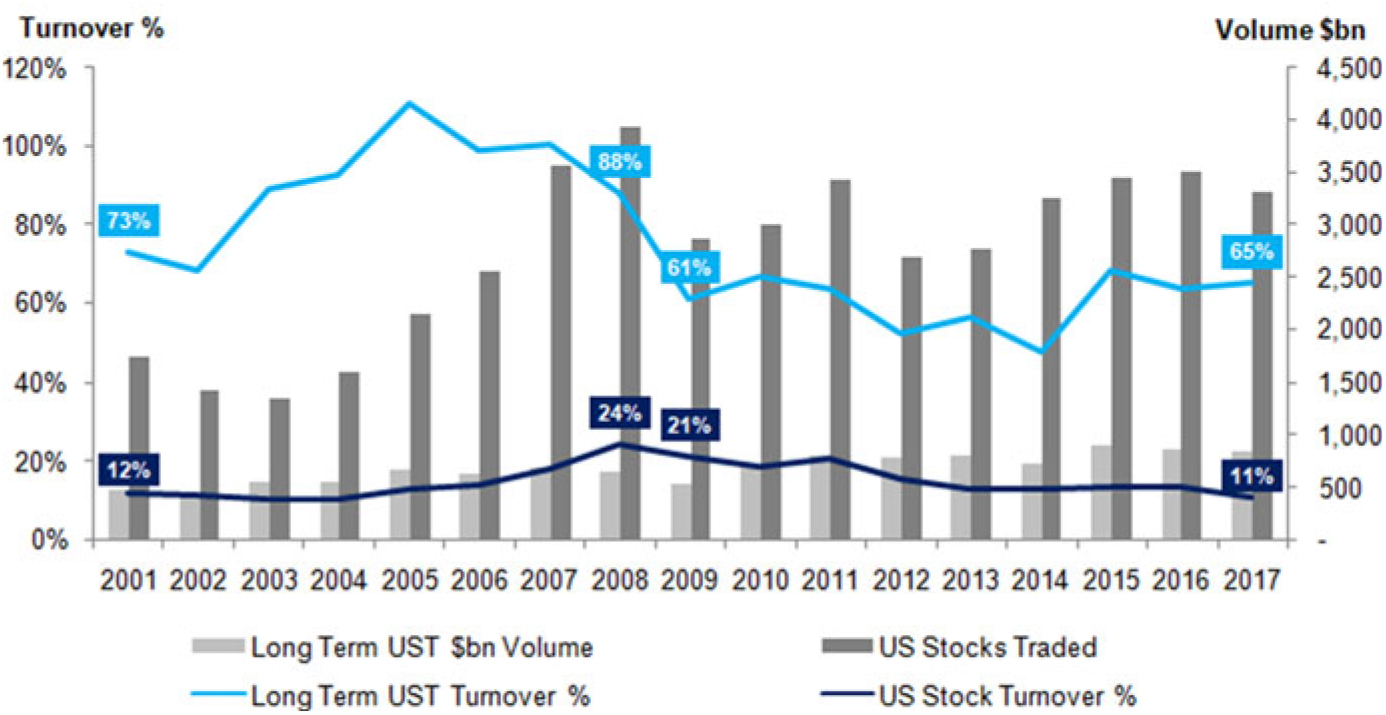

Marketability – reflects the depth of the market, which is dependent upon the level of activity in the market. This can be reviewed through measures such as turnover ratio or trading volumes etc.

Resilience – indicates that assets prices are not significantly impacted by the level of market activity.

Immediacy – indicates that the time to complete transactions is low.

Further consideration of the marketability aspect of liquidity is considered in Appendix 3.

4.4.2 Liquidity considerations specifically for UK insurers and pension funds

In general, insurance firms do not explicitly hold capital specifically for liquidity. In SII however there are limitations on the matching adjustment (‘MA’) where the liabilities have variable cashflows, and this is similar to holding extra capital. The need to restore MA compliance within a 2 month time frame in a stress could incentivise firms to invest in lower return, more liquid assets such as corporate bonds rather than higher return assets such as illiquid assets.

Not requiring capital to be held in respect of liquidity risk could be viewed to be sensible because, in a liquidity event, holding capital is not necessarily viewed as a suitable mitigant. However, this does not mean that insurers should ignore the effects of liquidity risk.

Liquidity Risk is primarily a part of the Pillar 2 of the SII Directive. Organisations must have a robust governance system and demonstrate a proper risk management with respect to various risks including liquidity risk. In particular, the underlying objective is to ensure:

identification and proper assessment of all risks they are (or could be) exposed to;

maintenance of sufficient capital to face these risks; and

development and usage of better risk management techniques in monitoring and managing such risks.

It has been noted that the points mentioned here can be mutually contradictory, since identification and assessment of the risks in the economic context of the (long term) business do not always imply that more capital is the optimal approach.

Also, in accordance with SII directives, national competent authorities should ensure that in its risk management policy, the undertaking covers at least the following items with regard to liquidity risk:

the procedure for determining the level of mismatch between the cash inflows and the cash outflows of both assets and liabilities, including expected cash flows of direct insurance and reinsurance such as claims, lapses or surrenders;

consideration of total liquidity needs in the short and medium term, including an appropriate liquidity buffer to guard against a liquidity shortfall;

consideration of the level and monitoring of liquid assets, including a quantification of potential costs or financial losses arising from an enforced realisation;

identification and costs of alternative financing tools;

consideration of the effect on the liquidity situation of expected new business.

In terms of various assets classes, the SII directive specifically focuses on the level of mismatch in the payoffs of the assets and the liabilities and thus the management of the liquidity shortfall. Also, the level of liquid assets must be monitored and the potential costs or financial losses arising from an enforced realisation in the form of forced sale, repo etc. must be considered.

The consideration of stressed scenarios for insurers assumes that the banking sector will remain robust. As demonstrated in the financial crisis, such an assumption does not always hold – particularly under instances of extreme financial stress and so such scenarios may be considered as unrealistic in extreme environments. A full discussion on systemic risk is beyond the scope of this paper.

For pension funds, there is no explicit (regulatory) requirement for trustees to manage or quantify liquidity risks but it is one of the key considerations that trustees should consider when setting the investment strategy:

Your strategy should be appropriate for your liquidity needs, for paying benefits and expenses and for any collateral requirements. It should take into account the risks introduced if your scheme is significantly cash flow negative, or is expected to become so in the futureFootnote 11

4.5 Humans, traders, incentives and heterogeneous risks

Whilst actuarial and investment issues obviously influence the investment approach for long-term investors, there are a number of other softer, often unobservable, factors that influence the investment approach.

4.5.1 Human emotions and investor trading behaviour

In particular, risk is not just an objectively quantifiable number – it also depends heavily on people’s perceptions, emotions and expectations. As such, understanding the economics of the investment approach is not identical to the unambiguous logic of mathematical equations. The literature on behavioural economics is comprehensive and outlines how real life decisions made by individuals can vary to those implied by classical theory. For example, due to:

Heuristics: the human mind desires to understand the world, and seeks a few simple, elegant ‘rules’ to ‘elegantly’ explain as much of the world as possible and the basis on which to make decisions (‘rules of thumb’).

Framing: whereby anecdotes and stereotypes might influence the way in which individuals understand and respond to events.

Market inefficiencies: for example, as demonstrated in momentum effects for stocks or how social paradigms change over time and cycles of fashion exist (e.g. whether companies are private/public, sources of funding, role of government/social protection).

Some of these theories can be used to explain some of the issues outlined above – for example, whilst some fear is essential for survival, excessive fear can be damaging (e.g. paralysis, stagnation) especially if socially transmitted, amplified and reinforced over time.

The role of surrogate decision making, whereby decisions are taken on behalf of others (e.g. pension Trustees) amongst long-term investors might also influence the level of risk being taken. Surrogates often display more muted behaviour (in investment decision making) converging towards more socially accepted choices. As surrogates want to be socially seen as making the right public decisions on behalf of others, their decisions may inter alia be influenced by self-image preservation and may create a bias towards more conservative choicesFootnote 12 .

4.5.2 Behavioural incentives of different stakeholders

Behavioural aspects also play a most influential part in the socioeconomic context. One crucial consideration is that there are asymmetric incentives impacting on some important decision makers. The regulator itself faces substantial risk from loss-causing events but has scant incentives to optimise the economic growth in the country’s economy. This impact is compounded by the fact that the preferences of public policymakers tend to lean strongly towards conservatism to avoid any need to support financial institutions under any circumstances.

There is a trade-off between the level of security and the price the consumer has to pay for that insurance… The price the consumer has to pay for that is something that they will not get a choice in. That choice is made by the regulatory system.Footnote 13

Whilst the topic of behavioural economics is vast and thus a full discussion is beyond the scope of this paper, its relevance to the theme of investment risk should not be ignored.

4.5.3 Risks are heterogeneous

Notwithstanding the human inclination to want to simplify, treat things uniformly and with a common base, and assign an arithmetic value to quantities, it should be recognised that there is no one homogeneous ‘substance’ called ‘risk.’ In Section 4.3, we highlighted how risk was inherently subjective and ‘in the hands of the holder.’

Further, different risks might need to be mitigated in different ways. Whilst there is some degree of interdependency, liquidity risk and credit risk should not be confused – they are hedged substantially differently.

Whilst capital can act as a buffer against credit risk, it is not necessarily appropriate to hedge liquidity risk. An investment portfolio’s economic exposure to credit risks is mitigated by instrument holdings diversification, for example, across the layers of an issuer’s capital structure, across different industrial sectors and geographies. In sharp contrast, liquidity risk cannot be similarly hedged by increasing the number of distinct portfolio holdings, it is a risk which varies with the investment markets’ supply/demand reactions and trading over time. Holding capital is not the only, and indeed often not even the best, way to mitigate risk.

4.6 Application to different investor types

A short description of how the risks outlined above affect the main investor classes and other considerations in setting investment strategy is outlined below.

4.6.1 Life insurers

Insurers have structurally disinvested in equities over many years, and as mentioned above now account for only a small portion of total growth assets invested in the UK. This is partly driven by consumers losing confidence in with-profit products and by the rise of unit-linked products where the choice of investment is not within the control of the insurer.

Insurers are very heavily regulated – this, along with accounting rules and conventions, is a key driver of asset allocation. The situation is exacerbated by the introduction of SII where liabilities are valued on a market consistent basis.

The EU regulatory capital standard under SII is a one-year value at risk measure. By this we mean that risk is measured over a one year period based on a certain probability of loss. For the SII regulatory capital requirement, the Solvency Capital Requirement (‘SCR’) is set as the 99.5th percentile loss over the one-year period. This could potentially be viewed as putting too much emphasis on short-term volatility instead of focusing more on long-term volatility. SII makes some allowance to reduce pro-cyclical effects and recognising the long-term nature of liabilities (for example, through the equity dampener, use of volatility adjustment (‘VA’), matching adjustment (‘MA’), etc) but these measures are often rigid and may be viewed as too prescriptive.

The Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (‘ORSA’) under SII encourages firms to perform their own bespoke analyses, including carrying out long-term run-off modelling on their own assumptions and use that modelling to set their investment strategy.

Liquidity considerations are typically managed through internal management controls of liquidity planning, for example, assessing the liquidity needs in various liquidity stress conditions. The balance of liquidity depends on the mix of business written where, for example, a closed with-profit fund running-off is likely to have a proportionately higher liquidity requirement compared to an annuity fund which is actively writing new business.

4.6.2 General insurers

With shorter tailed liabilities, the investment focus for General Insurers tends to be over shorter time horizons. However, the provision of PPOs are increasing the investment outlook for some General Insurers – particularly in respect of their larger claims for which PPOs are more prevalent.

A large number of PPOs are provided from, or near, the public sector (for example, through the NHS Resolution in respect of clinical negligence) which means that the principles of investment are either not applicable (because the pay-as-you-go nature means there are no funds held) or the principles are distorted.

For regulated private sector General Insurers that provide PPOs, the extent to which the investment strategy is more focused towards the longer term depends on the number of settled PPOs. Whilst there are external factors and trends influencing PPO propensity, the insurer will have their own views and some influence on the extent to which claims settle as PPOs. The key issue in this regard is the relative attractiveness of a PPO against a lump sum settlement, with claimants weighing up the size and risks of different award types and insurers weighing up the capital consequences.

Although an insurer may have some influence over whether a claim settles as a PPO or not (through the settlement process), ultimately a PPO can be imposed by the Court and so this may present a significantly different investment challenge to what a General Insurer is used to. In particular the main challenges to a PPO provider are:

The liabilities are often significantly longer than a General Insurer’s other claims risk.

The insurer is exposed to the longevity risk of the claimant living longer than expected.

PPOs are normally linked to an earnings index (‘ASHE’) which cannot be readily hedged.

There is the possibility of a step increase in the amount payable if the PPO is reopened as the claimant’s circumstances change.

As such, the ‘interest rate risk’ that is usually a small component of the overall risk for a General Insurer (relative to Life Insurers and Pension Schemes) can become more significant. There are though potential benefits to the insurer in that PPOs have a lower liquidity requirement – due to the immediate cashflow requirement being lower.

Many insurers make use of reinsurance to share the risks of PPO claims. Whilst to some extent this may reduce the insurers’ overall level of risk, some PPO reinsurance contracts allow for the reinsurer’s share to be capitalised – hence meaning the General Insurer bears all of the investment risk.

4.6.3 Pension funds

In the pension landscape, there has been an obvious shift towards Defined Contribution (‘DC’) schemes where the investment and longevity risk is borne by the individual. Whilst funds are still managed by institutions, and the investment choices made by individuals may be subject to the behavioural biases discussed in this paper, we have not considered DC pensions as part of our core focus – as they relate to individual investments.

For Defined Benefit schemes, their investment purpose is to provide retirement security in the form of real purchasing power for retirees. Risks to a pension fund include longevity, domestic economic performance and wage growth. Essentially pension funds want investment returns to hedge against the risk these factors pose to the level of contribution rates and benefits paid.

As benefits payable to members are defined, shortfall risks are borne by sponsors. In reality, if at all, ultimately only a State can afford to offer guarantees because of the taxation power. Not only do most private sector entities not possess such a source of finance but also few private sector directors truly understand the nature of an open-ended financial guarantee.

Broadly speaking, before 1997, most pension increases were either discretionary or guaranteed at minimal levels. That changed for all future benefit accruals and for some schemes for prior benefit accruals.

Over the past 20 years or so, financial economics has become generally accepted by UK pension actuaries as the dominant approach to assessing funding requirements. Whilst this provided the basis for funding approaches, some highlight that there is no evidence that this can be relevant to long-term entities. The theoretical academic evidence related to perfect markets, but perfect information is not generally available, and it cannot be (Grossman & Stiglitz, Reference Grossman and Stiglitz1980).

As a separate rationale, it was vigorously stated that using bond yields was, in any case, prudent, so not understating the liability was seen to be in the members’ best interests. However, prudence can only be identified from the best estimate, which is rarely, if ever, disclosed to stakeholders.

Further, discounting cashflows to a single liability value on which to make funding and investment decisions suggests a greater degree of certainty about the future than can be justified. Using capital values fails to allow the communication of the many risks and rewards that may lie ahead and their relative likelihoods.

Since 2003, the vast majority of private sector defined benefit schemes have been closed. This has had the effect that more of the benefits than before have become guaranteed. That has led to sponsors and trustees being advised to switch very largely from real assets to bonds. During the last decade since the crisis, bond yields have been exceptionally low, especially for index-linked gilt-edged stocks. The value is hard to discern. If anything, given that the cashflows stretch far into the future, a pension fund should be a natural home for ‘patient capital’ (see FCA consultation for DC plans, announced 12, December 2018).

4.7 Other considerations and constraints

In practice, investors such as long-term insurers and pension funds are unlikely be able to manage their business on a ‘pure’ economic basis of solely targeting returns and profitability whilst managing risks such as investment shortfall risk. This section will briefly mention two of the most onerous constraints on economic business management, namely regulation and accounting rules and conventions, noting their market structural impacts.

It has been mentioned earlier in this paper that a focus predominantly on regulatory capital can have perverse incentives, and additional capital costs/expenses incurred are not necessarily financially optimal or in the best interests of the ultimate beneficial investor or customer. We now consider each of the insurance and pensions areas in turn, taking a look at the history and current state of play of the UK regulatory environment.

4.7.1 Insurance companies

Currently, rules for the amount of capital that UK insurance companies must hold are specified in SII regulatory regime, Directive 2009/138/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (2009), which came into force with effect from 1 January 2016. Since then, there have been a number of ongoing consultations and discussions addressing the real and perceived shortcomings of, and potential improvements to, the existing specifications.

Article 101 under the Level 1 Directive sets out the methodology for calculating the Solvency Capital Requirement under the SII framework. Paragraph 3 of Article 101 sets out the time horizon for this purpose:

3. The Solvency Capital Requirement shall be calibrated so as to ensure that all quantifiable risks to which an insurance or reinsurance undertaking is exposed are taken into account. It shall cover existing business, as well as the new business expected to be written over the following 12 months. With respect to existing business, it shall cover only unexpected losses.

It shall correspond to the Value-at-Risk of the basic own funds of an insurance or reinsurance undertaking subject to a confidence level of 99.5% over a one-year period.

Under SII’s Standard Formula, the base equity shock is 39% for Type I equities (equities listed in countries which are members of the EEA or the OECD) and 49% for Type II equities (all other equity types).

There are various measures within the SII framework which allow some mitigating offsets to the severity of the specified shocks, and these are touched on briefly later in the notes that follow.

In late 2016, the UK Treasury Select Committee (‘TSC’) launched an inquiry into the SII regime. A number of pertinent points were raised by several key respondents:

Impact on equity investment and other real assets

The IFoA was of the view that ‘market consistent approaches have discouraged investment in equities other than where the policyholder bears the risk, such as on unit-linked business.’ There are both positive and negative perspective to consider:

1. From a positive perspective, ‘it discourages firms from giving over-generous guarantees and ensures de-risking can take place at short notice.’

2. However, this could disincentivise investments in ‘long term risky assets’. ‘For example, if the objective is to generate strong real returns with say a 20 year investment horizon then equities are a good asset as over this time period their returns are likely to be highly correlated with long term inflation impacts as indicated through the long term equities value creation review under Section 4.3. However, SII imposes a one-year horizon for capital and over that time period equity returns may be strongly negatively correlated with inflation.’

(By way of background, ‘Actuarial risk principles’ Section 6. on ‘Measure the risk’ states that one should allow for possible effects over the full time horizon of interest: different factors may be more prominent over different time scales. It is important to clarify which time horizon is most important for the stakeholder, so that we can focus on considering the right system drivers for that period. For full details, see Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (“IFoA”) (2017). Risk management – an actuarial approach.)

Due to the stringent requirements underlying SII and in particular the matching adjustment constraints, companies have had to jump through many ‘hoops’ before including suitable asset classes within the matching adjustment (‘MA’) portfolio. These include the need to create ‘“matching adjustment friendly” (e.g. decomposing property assets into income strips and residual property values due to the need for asset cashflows to be fixed unconditionally to be matching adjustment eligible). This type of activity does not lead to any reduction in investment risk. Indeed, the additional complexity adds operational risk, creates asset valuation challenges, reduces transparency and adds cost.’ Footnote 14

Criticism of market consistent principles and 1 year value at risk (‘VaR’)

Some criticism from the industry highlighted that these principles could encourage pro-cyclical behaviors which causes systemic risks. Market consistent techniques are neither stable nor verifiable for the full range of assets and insurance liabilities. Embedded within market-consistent valuation methodologies is the fundamental belief in the efficient markets hypothesis (i.e., that at any given time and in a liquid market security prices reflect all available information; it is not possible to know that you could know more than the current price).Footnote 15

The 1-year VaR framework is not necessarily considered to be compatible with insurer’s long-term liabilities where there this method may ‘fail to capture the path dependency of risk factors beyond the 1 Year period.’

Furthermore, valuing a long term business on a 1 Year basis is at odds with the time horizon of a going concern enterprise or the new requirements for directors to provide a long term viability statement in the annual report, since it says little about the ability of an insurer to meet its liability-related cash flows as they fall due.Footnote 16

Some SII mitigants

The long-term guarantee packages in the form of MA and volatility adjustment (‘VA’) helps balance things somewhat but these measures are still viewed to be overly prescriptive and perhaps opportunities for a principles-based approach may be available post-Brexit. While MA has a generally high take-up in the UK, on VA, there appears to be general consensus that the rules are too rigid. Recently, there has been discussion between major industry players and the regulator on possible ways to evolve a more dynamic VA.

Table 4. Regulatory versus accounting buffers. Source: Legal & General Group plc written response to Treasury Committee enquiry SII (SOL0009 of November 2016)

Further unintended consequences of stringent time-sensitive capital regulations could include wider macroeconomic impacts: there is greater systemic risk. The market-consistent elements of SII encourage behaviours which tend to move all market participants in the same direction simultaneously, thereby increasing the risk to the financial system as a whole on a much larger scale. SII’s rigidity is illustrated in Table 4, where it is contrasted to the accounting approach to the balance sheet.

In summary, notes from the EU High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (‘HLEG’) (2018) seem to express the issues concisely:

Solvency II currently bases a number of important elements – such as the setting of discount rates, the determination of risk margins and the calibration of charges for investment risk – on the assumption that insurance companies trade all their assets and liabilities at any point in time. This assumption is not consistent with the long-term business model of insurance and with economic reality. It is also not consistent with the wider desire and benefits for significant market participants to maintain and even grow their long-term approach to investment.

The obligation entailed in the IFRS accounting rules to use current market values for equity investment further discourages the use of equity for long-term investment – an issue that the Commission has committed to investigating in 2018. This investigation has the potential to unlock significant equity investments, while at the same time paving the way for improvements in the risk/capital regime. A more long-term, stable accounting framework would bring the reported balance sheet much more in line with the actual business model, and solutions found there could feed into the Solvency II 2020 review. By way of scale, even if only one percentage point of assets were to move from debt to equity, this would entail additional equity investments of €100 billion and reduce the debt bias in the EU economy. More specifically, it will be important that the upcoming IFRS 17 accounting standard ensures a combined working of accounting standards of assets and liabilities, as these are managed jointly in the insurance sector.

4.7.2 Pension funds

Introduced in 1997, the Minimum Funding Requirement (‘MFR’) was discontinued in 2006, with the advent of the Scheme Specific Funding Requirement (‘SSFR’, see below). It was intended to provide a simple uniform approach for determining whether or not a discontinuing scheme would have sufficient assets to secure the accrued benefits with a specialist pension provider. Originally, it was intended to be the Minimum Solvency Requirement but that was thought to be too ambitious an objective. In reality, the MFR was insufficiently tied to the actual market cost and was seen to have failed. The idea of uniformity was also held to be out of place and the SSFR was introduced in 2006.

Sponsors had already had to take account of revised pension accounting standards, with FRS17 Retirement Benefits introduced in 2003Footnote 17 and IAS19 Employee Benefits introduced in 2005. The differences between the standards were not that major but they were applied to different types of organisation. These accounting regulations, along with falling bond yields with which the accounting basis is set, led to large accounting pension deficits being shown on the sponsors’ balance sheets, which led to some pension schemes being discontinued.

In June 2003, the Debt Upon Employer regulations were enacted without any consultation. This new legislation made solvent sponsors responsible for pension scheme discontinuance benefits.

Tied to each pension scheme’s circumstances, the trustees were placed in control of funding requirement assessments. Taking advice from their own actuary and from no others in relation to benefits funding, they also had to agree their Statement of Funding Principles with the sponsors and comply with the Pension Regulator’s strictures. Trustees were specifically permitted to set a discount rate which took account of returns on the assets held, but most trustees elected to opt for gilt-based yields. Since 2007, especially after the June 2016 Brexit referendum, those yields became increasingly lower, with correspondingly higher capital values of the perceived liabilities. With actual investment returns having failed to keep pace, the assessed deficits (or shortfalls) became very much higher, with sponsors becoming even less willing to continue the pension scheme.

Because trustees were being told that they needed to match their benefit cash flows, a greater emphasis was placed upon gilts and bonds than real assets. That such asset transfers were made when gilt yields were very low led to real substantial losses.

Indeed research by OECD and Oliver Wyman showed that between 1980 and the mid-1990s, UK pension funds steadily invested between 60-80% of their investments in equities. Since then, UK pension fund’s exposure to equities has steadily declined such that by 2008 the exposure to UK equities was below 40%. In their report, the OECD and Oliver Wyman highlight:

The timing of changes in the regulatory regime and how this coincides with changes to funding regulation – in particular, the introduction of MFR in the mid-1990s coincided with the start of the decline of equity exposure.

Trends in the United States and Netherlands and how exposure to equities in those countries has actually risen slightly over the same period.

Despite the clear trends, there are some schemes bucking them. For example, the BAE Systems Pension Scheme recently noted:

More than 50 per cent of our assets are invested in equities and property… we’ve come to the conclusion that linking to gilts doesn’t make much sense for us.Footnote 18

4.7.3 Insurance interactions with pension funds

Throughout this paper we have generally considered insurance companies and pension funds separately to reflect the different regulatory regimes that apply and the different investment approaches taken.

The authors recognise that in practice the two industries do not operate independently – in particular as pension funds continue to look for ways to secure their liabilities, for example, via buy outs. As such, there are occasions where pension funds in particular are required to quantify and asses their liabilities through an insurance lens.

As such, the linkage between the two industries is subtle but nonetheless real – and any regulatory differences between the two sectors (for example, regulation that presents barriers to insurers to accept long-term pension liabilities) impacts indirectly/directly on the ability of pension funds to de-risk without harming members.

For example, the existence of a matching adjustment for life companies has likely buoyed the bulk purchase annuity (‘BPA’) market, as pension funds continue to value pension liabilities using bonds yields irrespective of asset holdings. Against this, the existence of a matching adjustment also means that this will drive annuity providers taking on these liabilities, whether immediate or deferred, to invest in assets with fixed income flows (including inflation- linked where relevant). This is relevant for deferred BPAs where while in theory insurers could invest in equity / property during the deferred period and move into fixed income once in-payment, not having matching adjustment eligible assets on day 1 would mean that these liabilities would not be eligible for matching adjustment calculations.

4.7.4 Summary of this chapter

In this chapter, we:

Defined the scope of investors that we are considering. In particular we are focused on long-term institutional investors (such as life insurance companies, pension funds and general insurance PPO provisions).

Defined the concept of shortfall risk which fundamentally drives the approach to considering the appropriateness of risk measurement approaches.

Outlined how ‘riskier’ (i.e. more volatile) asset investment returns can become ‘less risky’ if the returns are considered over appropriate time horizons.

Outlined some of the other considerations that are taken into account when institutions determine investment strategies.

5. Risk measurement approaches

In the preceding sections, the concepts of long-term investors and economic shortfall were discussed. Since the cash flow shortfall is considered over a future period of time, it is evident that a vector of cash outflows and inflows should be projected. However, in practice there is enormous emphasis on balance sheet capital, a single-figure measurement. Whilst a single figure is intuitively appealing for its simplicity and familiarity, it can be misleading since it ‘loses’ the full information over the future projection horizon. It also distorts the position with an air of spurious accuracy. Worse, it permits no true reflection of all of the possible risks and rewards.

Nevertheless, this section will initially consider stochastic modelling projections and discounting to a (single) present value of capital.

5.1 Considerations of the risk measurement approach

When measuring risk and making decisions, there are likely to be a number of relevant considerations for an entity in determining an appropriate investment strategy. Those considerations for risk measurement approaches underpinned by stochastic models are outlined below, though many of these will also be applicable to other approaches:

1. The modelling methodology and bases, e.g. valuation methods and bases for liabilities including the discount rate structure selected

2. The projection time horizon of the liabilities: n-year, to ultimate

3. The asset calibrations: MTM on balance sheet date, one-year volatilities, n-year averages

4. The confidence interval applied to the distribution of results e.g. 99.5%

5. The shocks applied, e.g. magnitude, instantaneous/over 1 year/over n years

6. The measure applied, e.g. VaR, TVaR, expected shortfall

7. Communications: Showing stakeholders the range of results with probability curves

The choices made in respect of each of these points can have a material impact on the final result. This paper will discuss mainly the projection horizon, some alternative calibration methods, and considerations related to the modelling methodology and bases.

As previously discussed in Section 4.3, risk measurement approaches can sometimes be objective but are more often subjective. Importantly, however, this does not have to be restrictive – in fact it can be a necessity for a functional market. For an economically living and growing market to exist, it is essential for the risk distribution in the system to be dynamic, in a continuous flux: it needs a variety of players who have differing subjective assessments of value at different times for trading, or exchange of value, for value to flow and thus constitute a healthy financial ecosystem.

Further, no risk measurement approach will be perfect or fully comprehensive in capturing all emerging and/or unknown risks – for example, climate change or artificial intelligence. This shortcoming is not explored further in this paper.

5.2 The use and impact of discounting

Discounted cashflows to a present value are commonly used: both as its own measure/metric/yardstick, but also featuring within other risk measures. Indeed, discounting features in many of the risk measurement approaches considered throughout this paper. Before considering those, we briefly consider the simplifications and limitations of using discounting based approaches.

5.2.1 Discounting for long-term investors

Although the discounting principle has been known for 2 millennia, it was only adopted for longer-term finance in the late 18th century. If it were certain that a return of 3 % pa would be achieved for the next year, 103 due in a year’s time can be financed by an initial 100. By converting future cashflows to the present, it can be seen that the discount rate is the inverse of the investment return. In reality, the financial environment is far less secure, given the lack of certainty, much longer time periods and assets which are far more complex instruments than cash. Because the future is unknowable, no uniquely correct interest rate can be defined in advance. There is, in fact, one uniquely correct view of the future but this is not known in advance so that assumptions are needed.

Risk quantification is very poorly captured by scalars. Specifically, single numbers are not appropriate results for representing many future uncertainties, especially when we do not even specify what the result represents (e.g. the mean, median, mode, or a specified percentile?). Rather, multi-dimensional results with confidence intervals provide information which a deterministic approach based upon discount rates cannot convey.

Risks are only taken because potential rewards may reasonably be anticipated (depending upon the circumstances). If discount rates are used, then they need to be consistent with investment returns. Otherwise, systematic bias is introduced, which is a major problem with accounting numbers. While the stakeholders (including regulators) may want the results to be ‘prudent’, that can only be defined in relation to a ‘best estimate’ benchmark. Where the liabilities are longer than the assets, using bond yields alone may even be imprudent.

While capitalisation was the original actuarial tool, which was all we had, it is no longer the only tool available and it obscures more than it reveals (the ‘scalar impact’). Discount rates are simple and simplistic, readily available to anyone and dangerous in both the ‘wrong hands’ and the ‘right hands’. For long-term projects, the authors recognise that using discount rates alone is limited and it is more optimal to consider cashflows using a robust stochastic process, for which the technology is readily available.

5.2.2 Allowance for investment returns within pension scheme valuations

Although specifically permitted by legislation, pension scheme funding valuations in the UK typically do not make an allowance for expected investment returns in the discount rate used to value the liabilities. If they were to do so, then schemes could take credit within their liabilities for investing in growth assets. This could be seen as encouraging pension schemes to adopt a longer term investment perspective and allowing them to seek the greatest return over the long term. It also reduces the focus on short-term volatility. The drawback of this approach is that the valuations of the liabilities are dependent upon the assets held, which can be difficult to explain but the effort needs to be made. The ‘liabilities’ are really the estimated cashflows rather than the capital amount. Thus the liabilities do not depend upon the discount rate.

The discount rate used in pension scheme accounting valuations is based on the yields of high quality corporate bonds. ‘In 2003, the implementation of FRS17 was intended to quantify the true risk of a corporate pension promise. It was originally based on the premise that the credit spread between an AA rated corporate bond and a gilt represents a “small premium above the risk free rate”’Footnote 19 . However, the margins can be higher and gilt yields are not risk-free. Crucially, it would take alchemy to make the basic cashflows risk-free.