Important Note

This paper is intended to provoke thought regarding actuarial work involving Periodical Payment Orders (PPOs). It has been written by a collection of actuarial professionals with extensive experience working with PPOs.

The paper has not been written to provide professional guidance or advice for any process, actuarial practitioner or other associated professional. We simply could not provide the sufficient detail required to cover every possible situation involving PPOs.

The PPO Working Party hopes that reading the paper will help provide avenues of enquiry around the key considerations for actuarial professionals working with PPOs, whether new to PPOs and in need of signposting, or experienced practitioners wishing to add depth to their thoughts on the area. However, the Working Party cautions that such papers can quickly become out of date and even generic statements may not apply to individual firms or situations. The Working Party does not intend to provide guidance and could not do so effectively through this medium. The Working Party instead encourages actuaries to continue to develop their technical and professional skills in relation to PPOs, and apply their own judgement to their own challenges, and hopes this paper can be of help to actuarial professionals as they do this. PPOs generate complex liabilities that have far-reaching implications for organisations exposed to them and practitioners should seek out additional support if needed.

1. Summary and Recommendations

1.1. Summary

A member of the PPO Working Party at a meeting in 2014 asked, “what do we actually mean when we say a PPO?”. The members then challenged themselves to define what a PPO is, in a single sentence. They approached this from the point of view of the inception of an insurance policy, on which a PPO may later arise. After debate and deliberation, they arrived at:

A PPO is a contingent, deferred, whole-life, wage-inflation-linked, guaranteed, impaired-life annuity, where the identity of the annuitant and the size of the annual payments are unknown at policy inception (Periodical Payment Orders (PPOs) Working Party, 2014c, page 5).

Seemingly exhaustive, even this does not fit all PPOs. For example, some are indexed to the Retail Prices Index (RPI) rather than wage inflation and not all PPOs are for the whole life of the claimant. This definition does, however, set out the main challenges for actuarial professionals working with PPOs.

This paper consolidates the skills and experience of a wide range of actuarial practitioners who, in aggregate, have many years of experience learning about PPOs as they lead thought on this new area. This paper is not professional guidance or advice. Instead, this paper sets out ideas to provoke thoughts on assessing risk, modelling it and communicating it for actuarial professionals working in reserving, capital modelling and pricing.

It starts with a discussion of the background to PPOs and the risks associated with them, before moving on to specific discussions of the issues they present for data gathering and assumptions setting, best estimate valuations, capital modelling, pricing and financial reporting.

The Courts Act 2003 and subsequent court decisions defined the current form of PPOs, igniting a new challenge for general insurance practitioners. Not simply annuities, and certainly not general insurance risks, PPOs still provide a challenge today, especially for those encountering them for the first time and also for more experienced practitioners.

This new settlement method has brought about new risks to consider for actuarial professionals working in motor and casualty insurance, or any other line where a claim for future economic loss may arise in the United Kingdom.

Life contingencies have entered the sphere of general insurance in a new way. PPO claimants, upon whose life the payments are contingent, typically have brain and spinal injuries. The measurement of impairments to life expectancy from these conditions had not been explored extensively by actuarial professionals previously, and, due to lack of data, actuarial research is currently in the early stages of development. This makes it an even greater challenge for general insurance actuaries unfamiliar with longevity risk. There is risk from the level of mortality, projected trends and the inherent volatility of sometimes very small portfolios, where the difference between the life expectancy and the actual survival period can be very different.

As a relatively new settlement method, the propensity of PPOs is highly uncertain and presents a risk in itself.

Other risks, more common to life insurance, are important for PPOs owing to the very long expected duration of typical cases. Actuarial professionals have investment risk to consider, and for PPOs the inflation risk is unusual, significant and not currently fully hedgeable. There are two inflationary pressures acting: the indexation of periodical payments; and the inflation acting on the initial payment amount between the loss date and date of sealing the order, which has additional considerations beyond indexation reference, such as the attitude to which future losses should be included to indemnify the claimant.

Some PPOs also have an unusual risk written into them. They can allow for a change in the annual payment separately to periodical indexing, where a predefined event triggers the right for these amounts to be reassessed. This is often referred to as a variable PPO.

Long durations also pose further risks from the extended time periods: the length of exposure to counterparty default risk is longer; and administration is over longer timescales and may have implications in setting claims handling reserves for expenses.

Being complex and relatively novel, additional operational risk arises from the existence of PPOs. PPOs require additional data to be captured.

General considerations for gathering data and setting assumptions for PPO valuation models highlight that economic assumptions are likely to be linked to each other, and cannot be set in isolation. Other assumptions may also be interlinked. This paper highlights methods that could be considered when setting mortality assumptions, some of which may become more feasible as time progresses and more data becomes available, both internally and from external sources such as industry data and other jurisdictions.

From a reserving perspective, it is important to remember that the nature of the liabilities does not lend itself to triangulation. On top of bespoke general insurance methods, for example, determining propensities for claims to settle as PPOs, it is important to value the PPO amount using cash flow techniques. Cash flows allow for more explicit discounting as well as the timing and value of reinsurance recoveries. Keeping track of what proportion of PPOs is already reserved for in claims system estimates and accompanying projections is also an important challenge that the reserving actuary must overcome.

Models can be constructed with different levels of complexity. Regardless of whether a relatively straightforward deterministic cash flow model or a complex stochastic model is used, it should allow for reinsurance arrangements that are in place, mitigating risk by transferring it. This can be a complex area to understand, as it is common for treaties to have indexation clauses that will interact with the periodical payments.

No estimate would be complete without checking the sensitivity of the calculation and applying real-world scenarios to highlight risks.

Common to chain ladder reserving, but determined very differently, the actual-versus-expected results can be analysed for discount rate unwinding and mortality profit, for example.

The paper also explores the basic considerations for modelling a range of possible outcomes in the Capital Modelling section. Stochastic modelling is considered, with the need to balance parsimony with sophistication. Again, stress and scenario testing is an important consideration for validating models that have been created, especially since PPOs present accumulations of risks, dependencies between them and may need to capture behaviour over relatively long time horizons compared to other general insurance risks.

Pricing is another area in which PPOs should be considered. Large loss loadings may need adapting to allow for PPOs. Estimates of the propensity and uplift can be made to help assess this aspect, not forgetting key interactions such as those between reinsurance and capital. Pricing PPOs is obviously a more significant issue for inwards reinsurers of motor and other casualty business.

Common to all actuarial work, but essential in a growing, fairly new liability, is the importance of clear communication. This includes informing users on the limitations of work. For example, a capital model under a 1-year time horizon may give a much reduced sense of the level of risk to ultimate. The clarity and straightforwardness of communication is essential in gaining buy-in when taking decisions which lead to increased liabilities or acknowledgement of higher risk in a firm. Both of these may be essential for a firm’s long-term financial strength.

Consequently, the paper also touches briefly on reporting requirements. This is to help provide a start for actuaries interacting with those undertaking financial reporting. The main learning is that PPOs can again lead to new requirements. These requirements may differ for different financial statements, with two obvious and common distinct types being statutory and regulatory returns. Furthermore, it is important for those working in reserving, pricing and capital modelling to understand how their work will affect the financial results of their company or client if they are a consultant. Increased communication with financial reporting professionals may be needed to aid understanding on both sides. Requirements will vary depending on each reporting basis and the sanctions and consequences of inaccurate financial statements can be very severe.

This paper is just a starting point for actuarial professionals working with PPOs. With the valuation of PPOs often being highly sensitive to the assumptions, it is important that practitioners continue to build their skills in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the liabilities. PPOs will evolve as a settlement method over time, so actuarial practitioners will need to stay aware of developments arising and act on them accordingly.

Given the long-term nature of the liabilities, professionalism and ethics are also very important. Most people reading this paper have a strong chance of retiring before the liabilities they model are run-off. The long-term implications for the adequacy of the reserves and the business strategy should be considered when working with PPOs, as the claimants, fellow employees and company shareholders may all be depending on practitioners responsibly innovating to accurately model these relatively new liabilities for many years to come.

1.2. Recommendations

As with any new area, the recommendations for actuarial practitioners working with PPO liabilities revolve around increasing their knowledge of the nature of the liabilities and informing their stakeholders about PPO risks in the context of the firm’s wider business.

This includes the actuarial practitioner:

-

∙ increasing their knowledge on the features and risks of PPOs, and we hope they find this paper useful as a starting point;

-

∙ considering the most appropriate method of modelling PPOs in context of the business model and risk profile of the firm. Depending on materiality, this will normally mean using cash flow models, which are uncommon in general insurance;

-

∙ communicating the risks of PPOs to key stakeholders including the administrative, management or supervisory body of the firm;

-

∙ keeping up to date with developments in the external environment, for example, the impact of legal changes; and

-

∙ proactively working with connected practitioners and in particular life insurance actuaries to support each other, for example, supplying cash flows and risk information to asset management teams, working with accounting practitioners preparing financial statements involving PPOs, or working with claims professionals to understand the nature of the liabilities.

In order to provide future generations with greater mortality data on PPOs, we urge insurers to start classifying large losses and PPOs using the PPO Injury Classification developed by the PPO Working Party and industry partners. The classification is of the severity of claimants’ injuries and the degree of future care they may require. Please see Further Reading section for a link to both further information and the classification system itself.

PPOs also challenge an actuarial practitioner’s professionalism with a requirement to balance stakeholders’ needs against a background of very long duration liabilities which exist to support individuals that have suffered life-changing injuries and need care for the rest of their lives.

Continued professional development in this area is therefore important, in terms of keeping up to date with thought leadership on technical actuarial modelling of PPOs, keeping abreast of changes in the external environment and continuously taking into account the principles of the Actuaries’ Code.

2. Document Organisation and Scope

2.1. Document Organisation

All actuarial professionals can benefit from the background covered in section 3 and description of risks in section 4.

Specifically, reserving topics are covered in:

-

∙ section 5 investigating data requirements and assumption setting;

-

∙ section 6 exploring valuation techniques; and

-

∙ section 9 regarding reporting.

For pricing practitioners, on top of the background and risk overview there is a dedicated discussion of pricing issues in section 8. In addition, section 5 covers assumption setting in more detail.

There is also separate discussion of the issues which arise for those working in capital modelling in section 7. In addition, section 5 explores data requirements and assumption setting for PPO models in general in more detail. Section 9 includes regulatory reporting.

To highlight which area is being covered in each section, we have used the following icons at the start of each section:

2.2. Scope

This paper is primarily intended to cover the valuation of PPO liabilities in reserving, capital and pricing modelling. Although assets are commented on in regards to the risks of assets and liabilities moving independently, the paper is not intended to cover considerations on the asset side of the balance sheet such as a detailed exploration of appropriate investment strategies and asset-liability management. Further information on this can be found elsewhere including in a paper written by the PPOs Working Party (2014a).

In addition, the starting point of the paper is to assume that any large loss metrics used to build up PPO reserves have been reserved for adequately. This paper does not seek to discuss methods to project large losses in general.

The paper is specifically focussed on PPO liabilities arising from UK insurance policies, and does not discuss similar liabilities which may arise in other jurisdictions. While there is a bias towards the considerations relevant to direct insurers, the majority of the issues discussed are equally applicable to reinsurers.

3. Background

A PPO is an alternative means of settlement of a claim compared to a traditional lump sum. A PPO can be used to settle a claim for future liabilities that are due to be met by regular payments, in place of, or in combination with, a lump sum.

3.1. Legislative Background

In the United Kingdom, before PPOs, structured settlements had been in use since 1989 (Periodical Payments and the Courts Act Working Party 2005, page 5). With structured settlements, part of a claim is settled as a lump sum and part as a recurring payment. The Damages Act 1996 (Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1996) gave the courts the power to order a structured settlement, if both parties agreed. Section 100 of the Courts Act 2003 (Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 2003a) was implemented on 1 April 2005 and permitted courts in England, Wales and Northern Ireland to impose periodical payments as part of a settlement, even if neither party consented to it. The explanatory notes to the Act set out the aim of the legislation: “to promote the widespread use of periodical payments as the means of paying compensation for future financial loss in personal injury cases” (Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 2003b, page 224).

Whilst Scots law at present differs in regards to the imposition of PPOs from that of England and Wales, the Scottish Government has stated that they intend to: “provide Scottish courts with a power to impose a periodical payment order and to vary such orders in the future” (The Scottish Government, 2013). In practice, the imposition by courts of PPOs has not been extensively exercised, with only about 6% of the cases decided upon by the court being settled by way of a PPO, based on insurance industry data at the end of 2013 (PPOs Working Party, 2015a). This implies that most PPOs are agreed out of court before being sealed.

Since the landmark Thompstone case (Court of Appeal, 2008) and stock market crash in 2008, PPO settlements have become commonplace. The Thompstone judgement allowed index linking of the annual payments to care workers’ wage inflation instead of the historically lower RPI, making PPOs more attractive to claimants. At present it appears that they will remain an important method of settlement in the future. The Ministry of Justice’s second Discount Rate Consultation Paper for use with the Ogden tables issued on 12 February 2013 asks whether there are any issues relating to the “possible encouragement of the use of periodical payments” or whether the present level of usage of PPOs “is appropriate and no change is necessary” (Ministry of Justice, 2013).

Further information on the legal background can be found in earlier papers from the PPO Working Party, including the 2010 General Insurance Research Organising Committee (GIRO) Paper (PPOs Working Party, Reference Orr2010).

The legal framework that defines PPOs has changed over the years. Further changes in the future can clearly have profound effects on the propensity of claims to settle by means of a PPO and their subsequent value.

3.2. Features of a PPO

The description of the features of a PPO that follows is based on the PPO Working Party’s 2010 GIRO Paper (PPOs Working Party, Reference Orr2010).

Although PPOs can be used to settle any claim resulting from future economic loss, most orders awarded to date are for a subset: future care costs, with case management costs frequently included. Large future care costs tend to arise as a result of brain and spinal injuries. Typically, claims settling with PPOs include an initial lump-sum element to cover large upfront expenses, such as setting up appropriate accommodation, as well as future economic losses not settled as a periodical payment. It is quite common for economic loss and loss of earnings to be settled by lump sums rather than periodical payments. This gives flexibility in award levels.

The amount of the periodical payment will reflect the level of the future economic loss covered by the order and the needs of the individual claimant. The initial award is adjusted in future periods in line with changes to a specified index or survey, as detailed below.

The length of time a PPO specifies payments to continue will vary by head of damage. The claimant is generally eligible for future care costs for the remainder of their life. The payments in the order can be structured to reflect the changing needs of the claimant. An example is a stepped PPO: this will include a specified change to the award, at an identified future date. The change in payment amount could be to reflect the ageing of key carers, such as parents or spouses, or a greater need for care in old age. Economic loss or loss of earnings is likely to be paid up until retirement, or death if earlier. In cases where there is a fatality, periodical payments to dependants are likely to be set up until each dependant reaches a particular age.

Where there is uncertainty in the future course of a condition, the PPO may be a variable order, which either allows claimants to seek additional payments if a pre-specified trigger event occurs as a result of the original accident or the potential to reduce the amount if the condition improves in a pre-specified way. This is different to a lump-sum settlement alternative, where such protection is not usually part of the settlement.

The size of the award will take into account any contribution made by the local authorities. Where there are such payments, some insurers decide to pay all of the costs and require monies paid by the local authority to be repaid, whilst others pay the amount net of local authority funding. In the latter scenario, the PPO may include a review clause or indemnity guarantee against the possibility statutory funding is reduced or withdrawn at a later date.

A PPO is typically set up as an annual or semi-annual payment, payable in advance. To receive the payment, the claimant or claimant’s representative must provide proof of life, usually at least annually. On the claimant’s death, overpayment can be returned to the insurer, though due to the sensitive nature of such requests, insurers may need to assume differently.

3.2.1. Indexation

So far we have described the payments in real terms at the point of settlement. In practice, payments are index linked in nominal terms. The Courts Act 2003 originally allowed for payments to inflate annually, in line with the RPI index. This would allow insurers to match the liability by purchase of an RPI-linked annuity or other RPI-linked assets. Since the Thompstone case (Court of Appeal, 2008) where this feature was successfully challenged, wage-based indices can be used instead. A number of indices have since been used. This made PPOs more desirable, as wages should be a better proxy for inflation of the care costs, which in the past have typically increased faster than prices.

The most popular index in use so far is that selected by the judge in the Thompstone case: the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE). This is undertaken annually by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The survey includes a number of sub-codes, detailing the level of earnings for specialised professions at a number of percentiles. PPOs have generally provided for the cost of care. These have usually been linked to sub-code 6115 of ASHE: care assistants’ and home carers’ earnings. These workers will typically be those helping claimants with a combination of their personal needs, mobility and meal preparation. A percentile is selected in the order, consistent with the experience and hence remuneration of the carers required. ASHE reports in a number of formats, such as hourly earnings and annual earnings. PPOs settled to date have typically been linked to the hourly earnings rate. For example, the 80th percentile of the provisional 2015 estimate for gross hourly pay for sub-code 6115 was £10.38/hour, from an estimated population of 835,000 care employees (Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2016b). This is lower than the 80th percentile for all employees of £19.75/hour, from an estimated population of 25 million employees (ONS, 2016a).

Sub-code 6115 of the ASHE has not been straightforward to index payments. It is a survey rather than an index, and is consequently less stable as it averages over a less complete sample. Furthermore, in 2010 the ONS, as part of its 10-year review of categories, sub-divided 6115 into 6145 and 6146, relating to care assistants and home carers salaries and senior care worker salaries, respectively. Realising the importance of the category the ONS continued to publish ASHE 6115 on the old basis. While the ONS has committed to publish it for the foreseeable future, the index may not be available for the full duration of PPOs in payment (ONS, 2011).

It is possible for other indices to be named in orders, where agreed by both parties or imposed by the judge. These may be different ASHE sub-codes that relate to the nature of the award. In addition, awards have been made linked to RPI or in some cases a fixed annual increase has been agreed.

Relatively smaller costs included in the annual payment, such as case management costs, may have indexation applied at the same level as the principal head of damage or with reference to a different, more appropriate index.

The processing and updating of the annual amount following the publication of the survey, the costs of ascertaining any further medical reports and obtaining proof-of-life checks are continuing costs that are in addition to the payments themselves.

Table 1 shows a possible breakdown of a PPO with no adverse features, which could be, for example, a complex pre-accident medical history. The example case is for a person aged 22-year-old at the time of the accident, who now has tetraplegia having suffered a complete spinal injury at the C4/C5 vertebrae (PPO Injury Category S2). Settlement took 2 years, so there are 2 years of past losses. Future losses assumed to age 70 on an impaired life expectancy basis. The impaired age impacts the non-PPO future losses which were calculated using a 2.5% discount rate multiplier. Amounts are additional costs beyond those incurred if the accident had not occurred.

Table 1 Example Periodical Payment Order Claim Breakdown

This table highlights that a practitioner should not only consider the PPO risk, but where a claim is unsettled, there are risks that any one of the heads of damage could be affected by legal changes or developments in the prevailing claims environment. There remains the risk that additional heads of damage could emerge.

3.3. Prevalence of PPOs

In the United Kingdom, at the time of writing, there are PPO settlements in payment for motor, public liability, employers’ liability and clinical negligence claims. In theory PPOs can arise on any policy where there is an element of liability cover, including household cover. In practice low liability limits might limit the attractiveness of PPOs compared to lump sums. A lump sum is a discounted value of future payments and once invested may provide a total sum that is greater than the limit of indemnity after the settlement, assuming lump sums are discounted at positive rates of interest. A PPO payment stream is not discounted and so will reach the limit sooner.

There is wide variation in the prevalence of PPOs both by class of business and by insurer. The propensity for a large claim to settle as a PPO has been higher to date on motor than on employers’ liability and public liability products. This may be due to motor cover being unlimited in the United Kingdom and the previously discussed limits of indemnity for employers’ liability and public liability.

The prevalence of PPOs is also highly influenced by the market environment. As PPOs are indexed, if there are concerns that inflation may be higher than is embedded within the Ogden discount rate then a PPO may be preferred, all else being equal. Also, as the claimant receives the payments periodically, rather than a discounted lump sum, PPOs may be preferred if the investment returns embedded within the Ogden discount rate are higher than is achievable on the investment markets for the claimant’s attitude to risk. Consequently, it can be seen that the attractiveness of a PPO to a claimant will also be heavily dependent on the Ogden discount rate, which can be at odds with short-term economic conditions and concerns.

Other jurisdictions outside of the UK settle claims using various forms of periodical payments. The exact nature varies by country and also by product within the country. An annual amount that increases with inflation is paid in some countries and in others the required care costs are reimbursed. The PPO Working Party plans to publish a website providing its understanding of how several different jurisdictions settle claims soon. This will be available on the Working Party’s website, as provided in section 11.

3.4. Initial Actuarial Response

Since the introduction of PPOs, actuaries have continued to develop the sophistication of their models used for reserving, capital modelling and pricing for PPOs.

In reserving, the initial response was to use life techniques to value settled PPOs for the purpose of setting the reserves. Alongside this, models for capital analyses have developed in more recent years as consideration of the impact of these long-term liabilities on capital requirements has increased. Developments in pricing of direct business for PPOs has been slower, as large loss loadings are often very uncertain, as they are from an unknown third party and actual experience is volatile.

Reserving models of PPOs have developed over time. The distortion that PPO claims introduced to claims triangles forced practitioners to separate out these claims and consider them independently. The emerging changes to the regulatory environment, namely Solvency II, crystallises this requirement.

Initial reserving models generally used an annuity certain approach, typically taking into account:

-

∙ life expectancy – based on medical evidence to provide the expected length of payments;

-

∙ future inflationary and stepped increases;

-

∙ future investment returns; and

-

∙ indexation clauses within the reinsurance treaties.

The approach to potential future PPO claims was more varied. Many relied on claims handlers’ or solicitors’ advice to identify future PPOs, based on the severity or type of claim. The approach to calculate reserves for future PPOs used a combination of expected future numbers of large claims, the proportion of large claims expected to settle by way of a PPO, and the uplift to cover the higher PPO costs arising from real discount rates being lower than that prescribed to value lump-sum settlements, namely the discount rate prescribed for use with the Ogden tables, currently at 2.5% p.a. Allowances for Pure Incurred But Not Reported (IBNR) PPOs (those claims that at the point of valuation have not yet been reported) were not common historically, but have become a consideration in more recent years. A loading is often applied either in conjunction with the potential future PPOs currently identified as large claims or separately.

Over time, the models of PPO liabilities have moved from an annuity certain basis, to approaches using probability-weighted mortality, and adjusted life tables. Whilst we can only speculate as to the reasons for this, it is likely that the possibility that over time, if the claimant lived longer than initially expected, the two reserve estimates would materially diverge may have contributed to the trend. When cases do live beyond their life expectancies, probability-weighted mortality would more accurately reflect the reserve required and the expected reinsurance recovery.

3.5. Growth in PPO Reserves

Each year, newly settled PPOs are added to prior years’ PPOs already in payment. At present there have been few deaths amongst PPO claimants since 2008, when PPOs first became a commonly used method of settlement. This is in line with expectations. It will be many decades until the flow of new settlements is balanced by older PPOs ceasing to be paid. This means that the majority of individual insurers should expect that their PPO reserves will grow over time, and this should be reflected in their business plans. As the proportion of reserves held for PPOs grows relative to overall claims reserves, general insurers’ balance sheets may start to look more and more like those of life insurers (PPOs Working Party, 2014a).

4. Risks

4.1. Overview

The risk profile of PPOs has features that are not typically seen in other general insurance liabilities, or that are not seen to the same degree. It is important that this is communicated clearly by actuarial practitioners. A firm’s administrative, management or supervisory body need to understand the risks their firms are exposed to, recognising both the current risk profile and how this might change in the future. This will enable them to make informed decisions about their risk appetite, risk mitigation strategies, and ultimately make a risk and reward assessment of their participation in business lines which can be affected by PPOs.

We consider the risk profile of PPOs below, with a focus on risks that are either not present, or are less significant, for more typical general insurance liabilities. The risks we shall discuss in this section are:

-

∙ longevity risk;

-

∙ propensity risk;

-

∙ inflation risk and indexation risk;

-

∙ interest rate risk and other market risks;

-

∙ variable orders;

-

∙ counterparty credit risk;

-

∙ operational and expense risk; and

-

∙ additional considerations.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of all risks that an insurer with PPO liabilities should consider, but provides a structured way in which to consider the key risks arising from PPOs. Actuarial practitioners working on PPOs may wish to engage with colleagues responsible for an insurers risk identification processes and ensure that PPOs are being appropriately considered.

Furthermore, although discussions of risk often revolve around the downside, there may be material upside risks on PPOs. Claimants may survive for shorter periods than expected, propensities may fall, and inflation may be lower than expected. With such long-tail risks, at a relatively early stage in their emergence as a settlement method, PPO valuations are likely to be materially different from the ultimate result, and this could be in either direction.

4.2. Longevity Risk

Longevity risk is the risk of loss, or of adverse change in the value of insurance liabilities, resulting from changes in the level, trend, or volatility of mortality rates, where a decrease in the mortality rate leads to an increase in the value of insurance liabilities (European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA), 2009, page 5).

Once a claim is settled as a PPO, the term of future payments is contingent on the claimant’s survival. The longer the claimant lives, the more the insurer has to pay. This introduces longevity risk, which is not a typical feature of general insurance liabilities. Longevity risk is a common feature of annuity contracts, and consequently data and research on longevity is available. However, PPOs have characteristics that would be considered atypical for conventional annuities and hence have their own longevity considerations. In particular, PPO claimants are typically significantly younger than conventional annuitants. The average PPO claimant is around 35–40, but claimants can be in their teens or younger (PPOs Working Party, 2015a). In addition, the nature of their injuries means that they often have impaired life expectancy.

Impaired lives referred to in the context of life insurance products do not typically involve brain and spinal injuries. The term instead usually refers to people who have chronic conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes or cancer, and usually the products are for older lives than PPOs. This makes PPO longevity risk unusual and uncertain, and consequently risk transfer to a third-party may be significantly more difficult and costly.

Longevity risk can be decomposed in a number of ways. For the purposes of the discussion in this paper, longevity risk has been split into three sub-risks:

-

∙ Level risk: the risk that the base mortality rates have been estimated incorrectly at the outset.

-

∙ Trend risk: the risk that expected future mortality changes have been estimated incorrectly.

-

∙ Volatility risk: the risk that, even when the base mortality rates and mortality trend have been estimated correctly, individual life spans could still deviate from the average life expectancies.

4.2.1. Level risk

Level risk in the context of longevity risk refers to the risk that the estimated current mortality rates for a specific individual are incorrect.

This risk is influenced by the approach taken to estimate base mortality rates for PPO claimants. There are three broad approaches that could be adopted:

-

∙ Estimating a set of mortality rates that are appropriate for the entire population of potential PPO claimants, ignoring the impact of their injuries. Allowances for the impact of their injuries on life expectancy then need to be allowed for on a claimant by claimant basis.

-

∙ Estimating mortality rates individually for each claimant, utilising the available medical information.

-

∙ Estimating a set of mortality rates that are appropriate to the entire cohort of PPO claimants (or some relevant subsets) taking into account the impact of their injuries.

4.2.1.1. Estimates of mortality rates for the pool of potential PPO claimants

A typical starting point for producing base mortality rates will be to consider those derived from a suitably large and representative cohort of individuals, for example, the population of a specific geographical region, such as England. Despite the large sample sizes involved, these mortality rates are still subject to estimation error. In particular, at young and very old ages there are very few data points and the mortality rates will consequently be fitted to sparse data.

Selecting an appropriate base table is itself a matter of expert judgement. There are a number of different mortality rates predicting the mortality of various population cohorts in the United Kingdom. There is no guarantee that any single set of mortality rates will appropriately describe the population of potential PPO claimants, even before consideration impairment by their injuries. Actuarial practitioners should consider that a population of claimants with serious bodily injuries may be a biased sample of the UK population (age and sex aside). Additionally, the population of those which settle by way of a PPO may be further biased. For example, there may be a bias for certain socio-economic groups to prefer a lump-sum award.

4.2.1.2. Estimates of individual impairment for PPO claimants

Claimants who are awarded PPOs will typically have suffered significant and quite specific brain or spinal injuries (PPOs Working Party, Reference Orr2010, page 70), which means that it is often the case that the claimant is expected to have impaired mortality relative to a member of the general population.

Often during the course of a claims settlement, medical opinions are sought on behalf of both the insurer and the claimant in order to determine the estimated life expectancy of the claimant, taking into account the injuries sustained. Brain and spinal injuries can often be very specific to the individual, and consequently estimates of the level of impairment often vary significantly between different medical practitioners. Given that insufficient volumes of PPOs (or indeed large bodily injury claims) have been tracked over a sufficiently long period, there is no clear body of data from which we can fully understand the true level of impairment attaching to any particular level of injury. Estimates given by either side may therefore fundamentally under- or overestimate the levels of impairment. It is not uncommon for the two sides to have differing medical views on life expectancies. Actuarial practitioners should be mindful of the risk that, given the small body of research on which medical professionals are reliant in forming their estimates, the potential for this estimation error to be systematic is high. Furthermore, the impact of potential future changes in mortality rates (see the section on Trend risk below) may not be considered fully in any initial life expectancy assessments provided by medical professionals.

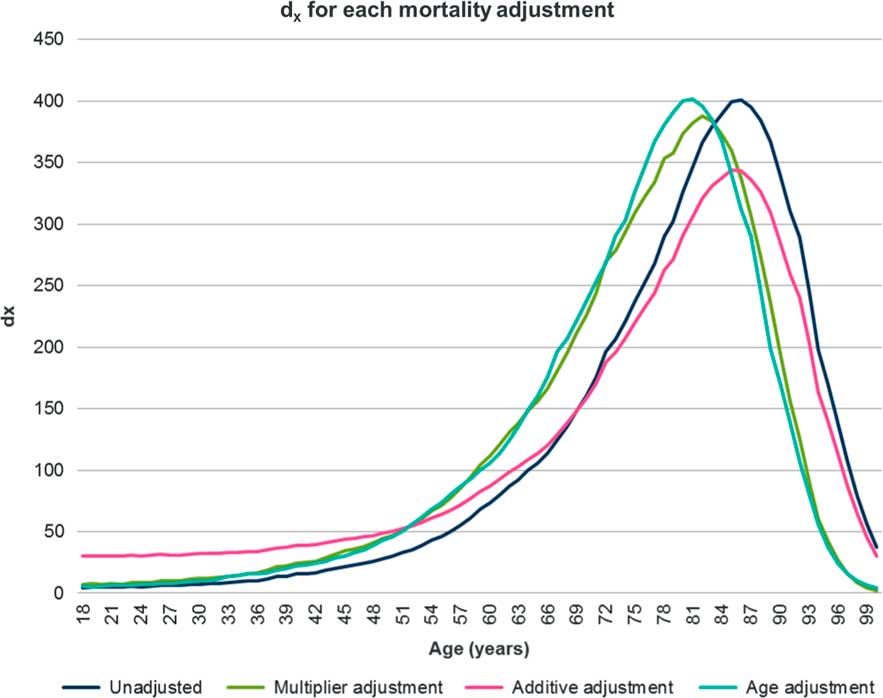

As discussed in section 5.5, there are also a number of different technical methods which can be used to adjust mortality rates for unimpaired lives to allow for impairment (PPOs Working Party, Reference Orr2010, page 71), each of which have advantages and disadvantages of which the actuarial practitioner should be aware.

As PPO claimants continue to age, it is not necessarily the case that the original assessment of impairment – even if correct – will continue to be appropriate. The claimant’s medical condition may change over time such that either their mortality improves or deteriorates relative to the original assessment. The ability for an insurer to obtain up-to-date medical information on the claimant will depend on the terms of the court order. In cases where it is not possible to obtain updated medical information, actuarial practitioners should consider carefully how to reflect original medical information that could be significantly out of date. In cases where there is the possibility to reassess life expectancy, there are often limitations concerning either the number of times or the circumstances in which it can occur. These will need to be considered on each case before updates are sought – they may be even more important over the many years of run-off for reinsurance and indeed corporate transactions.

4.2.1.3. Estimates of mortality rates specific to PPO claimants

In order to mitigate the risks associated with reliance on medical opinions, an alternative approach is to construct a set of mortality rates that are suitable for the whole population of PPO claimants, or relevant subsets. This implicitly takes into account the impact of their injuries on mortality rates.

This approach does, however, have significant challenges in gaining sufficient data. When life insurers estimate mortality rates for their annuity portfolios, they have access to industry-wide mortality rates and often have statistically significant death data of their own to fit appropriate mortality base rates. However, there are no specific sets of mortality rates readily available for PPO claimants or for individuals subject to the type of severe brain and spinal injuries typically suffered by PPO claimants in the United Kingdom. The number of PPO claimants in the United Kingdom is very low compared to the number of annuities written by life insurers, and it is likely to be many years until there are sufficient data points to enable any statistically robust set of mortality rates to be produced and even then, there may be insufficient data.

There are data sets available from other countries that can be analysed and used to help estimate mortality rates for individuals subject to the types of severe brain and spinal injuries typically suffered by PPO claimants (PPOs Working Party, 2014b, page 142). This, however, introduces additional basis risks due to a mismatch in relation to geographical and socio-economic factors, between the specific nature of injury types, and in the mixes of claimants by age and sex.

4.2.2. Trend risk

Trend risk refers to the uncertainty in estimating the future trends in mortality rates. General population mortality has been subject to significant improvement over time, and most forecasts anticipate further improvement in the future (ONS, 2016e). As well as allowing for the expected level of improvement in the future, actuarial practitioners need to consider the uncertainty associated with estimating future mortality rates.

Forecasting future mortality improvements for the general population is a subjective exercise, relying heavily on expert judgements. As previously commented, PPO claimants are often much younger than typical annuitants, introducing the need to forecast mortality improvements significantly further into the future than required by most life insurers and for a greater range of ages.

Future mortality could easily become lower both suddenly and beyond projected trends, for example, if a cure for dementia was found or cancers eliminated. The opposite effect is also straightforward to conceive: world wars, lethal pandemics or the failure of antibiotics would all increase mortality. Not each would affect PPO claimants in the same way as the general population. An illustration is war and a failure of antibiotics, with the former unlikely to directly affect claimants, as they would not be fit enough to fight, and the latter may affect them more, as being bed-bound with more frequent visitors for care can increase infection rates.

Additionally, focussing on PPO claimants, medical advances related to specific brain or spinal injuries could suddenly significantly increase life expectancies for PPO claimants. Changes in social care regimes may also change mortality trends for PPO claimants.

Any error in estimating future mortality improvements could be applicable to large proportions, or indeed to all of the PPOs within a portfolio, therefore the importance of this risk increases as the number of PPOs increases.

4.2.3. Volatility risk

Volatility risk could also be referred to as process risk or statistical risk and refers to the inherent risk from any random process. In this case, the risk that, even with a perfect estimate of the expected current and future mortality rates for a given claimant, the claimant lives longer or shorter than anticipated.

The latest PPOs Working Party survey (2015a, page 5) identified around 400 PPOs in the market, and even with a large market share it is likely that the total number of PPOs will be below 100 for most large insurers. At this level, volatility risk can be significant. This risk becomes more acute the smaller the total number of PPOs an insurer has, or in cases where there are particularly large individual PPOs that dominate the total PPO liabilities for an insurer. This risk is relatively peculiar to PPOs, as life insurers will typically have portfolios of lives that are several orders of magnitude larger as well as access to the life reinsurance market.

4.3. Propensity Risk

Propensity risk refers to the uncertainty associated with the future propensity for individual claims to settle by way of a PPO, rather than a lump-sum settlement.

Whilst dependent on the assumptions adopted when valuing PPOs, at the time of writing it is typically the case that a PPO settlement has a higher expected cost than a lump-sum settlement on equivalent terms (PPOs Working Party, 2015a). This is a result of the current market-consistent real rates of return being significantly lower than the 2.5% p.a. real discount rate for lump-sum settlements. The risks associated with a lump-sum settlement are also largely extinguished at the point of settlement, whereas the risks associated with a PPO settlement will continue until the death of the claimant. An increase in the propensity for claims to settle as PPOs will therefore tend to have an adverse effect on both a firm’s best estimate liabilities and its capital requirements.

Propensity can be affected by a number of factors. These include, but are not limited to:

-

∙ changes arising from court precedent, for example, the Thompstone case (see section 3.1);

-

∙ changes in the discount rate prescribed for use with the Ogden tables used in valuing lump-sum settlements;

-

∙ changes in the wider economic environment, which may influence the perceived value of a PPO settlement compared to a lump-sum award;

-

∙ changes in social trends influencing claimants’ preferences or changes in the claims handling practices of the insurer.

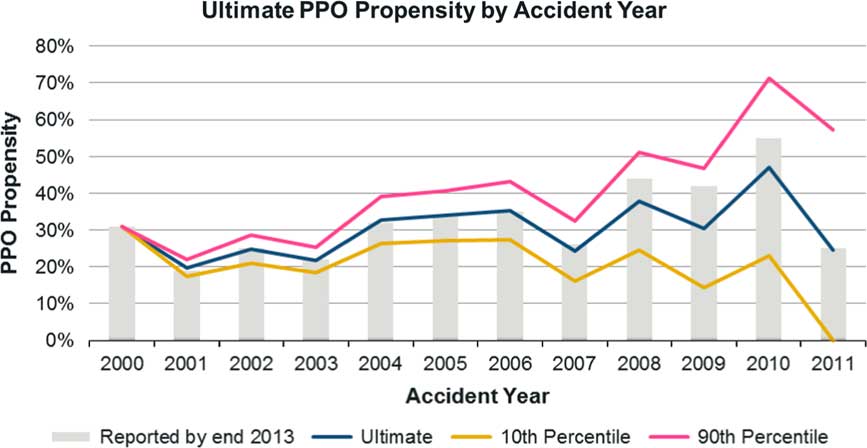

Figure 1 shows the propensity for a claim above £1 million (in the 2011 settlement year, indexed at 7%) to settle with a PPO, based on data as at the end of 2013. It shows a very approximate chain ladder estimate of a potential expected ultimate position together with the corresponding approximate 10th and 90th percentiles using Mack variability and assuming a normal distribution capped at 100% and collared at 0%. (The actual percentiles may be much wider due to the low volume of condensed data used to estimate the percentiles; PPOs Working Party, 2014b.)

Figure 1 Potential accident year Periodical Payment Order (PPO) propensities

For an insurer settling low numbers of large bodily injury claims, the inherent risk of whether or not specific large bodily injury claims do, or do not, settle as PPOs can also be significant, even if the rate could be predicted with certainty.

At the time of writing the discount rate for lump-sum settlement is 2.5% p.a. Compared to a market-consistent valuation a lump-sum valued using a 2.5% p.a. real rate of return would seem to give a lower economic value, all things considered. The table below highlights the impact of different discount rates. Table 2 shows the difference in the Ogden discount factor (7th edition) for a 35-year-old male. For a negative 1.5% factor, the reserve for cost of care would be 200% higher, and thus a lump sum with this discount rate would change the relative economic attractiveness significantly, thus highlighting the importance of this assumption to PPO propensity.

Table 2 Impact of Different Discount Rates

There is a considerable degree of uncertainty over the value of the discount rate used to value lump sums in the future.

4.4. Inflation and Indexation Risk

Inflation risk refers to the risk that the future indexation of payments under a PPO award differs from that anticipated.

As with many other features of PPOs, it is not the case that actuarial practitioners can rely solely on the experience of annuity providers writing index-linked annuities, as there are significant differences between the indexation arrangements for PPOs compared to typical annuity products.

First and foremost, future payments for PPOs tend to be linked to a percentile of ASHE 6115, although other indices are also used (PPOs Working Party, 2015a). ASHE 6115 is an ONS survey of the wages for care assistants and home carers (ONS, 2013). If we consider traditional index-linked annuities, these tend to be linked in some way to price inflation (RPI, or a function of RPI such as Limited Price Inflation). Whilst there is a deep and liquid market in RPI-linked assets, there are not currently any investment products widely available that provide a return linked to general wage inflation, let alone changes in the wages of a specific percentile of a specific sector of employment. Therefore, there do not appear to be assets at present that can be used to completely match liabilities that are linked to ASHE 6115 (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Lee and Jamieson2013).

The consequence of this is that, given the long duration of PPO liabilities, uncertainty in the level of ASHE 6115, or any other indexation method other than RPI, is typically a material risk to an insurer with PPO liabilities, which is very difficult to mitigate.

The levels of RPI and ASHE 6115 depend on the relative supply of and demand for products and services and care assistants’ labour, respectively. Phenomena such as these are impossible to predict accurately over a very long timeframe. Care workers’ wage inflation could be materially different from general wage inflation in the future, especially since it is an area of the economy that has the potential to be distorted by the actions of the state. This gives insurers a challenge in selecting values for ASHE 6115 in valuing PPO liabilities and also in matching those liabilities with suitable assets.

When considering the risk from ASHE 6115 linkage, actuarial practitioners may in some cases choose to deconstruct the indexation into the RPI component and the difference between the ASHE survey and RPI. Where the RPI component of the liabilities is well-matched with RPI-linked assets in the firm’s current asset portfolio and future investment strategy, the RPI inflation risk can be considered in a more traditional way and any mitigation from liability matching considered. When analysing the risks inherent in the difference between ASHE indices and RPI, actuarial practitioners may consider the general level of wages in the economy compared to RPI and the extent to which the trends in care workers’ wages may differ from those of the general population.

ASHE 6115 has historically been the most common survey to which PPOs are linked. As explained in the Background section, in 2012 the ONS stopped publishing ASHE 6115 within the main body of the ASHE data, and reclassified the index in two parts. At some point, the ONS may stop producing the ASHE 6115 data, and although many PPOs have a formula in the order to adjust for previous and future basis changes, there is uncertainty as a result. What is a similar survey or index, when the original is so specific? There is a risk of indexation basis change across the portfolio if ASHE 6115 were to be discontinued.

For PPOs not yet in payment, insurers are also exposed to another source of inflation risk between the valuation date and the date of settlement. Future award levels may differ from those awarded historically, for example, due to changes in the structure of care regimes proposed, or changes in the scope of costs covered by PPOs. For those settling out of court especially, there are also influences from the relative negotiating powers of the claimants’ and defendants’ representatives. This source of inflation is similar to but not the same as typical large claims inflation, and is easy to overlook when so much focus is on the indexation of the periodical payment award once in payment. An example of a source of inflation to the initial amount is allowing for support for carers to assist with holidays, on top of regular home care assuming no support.

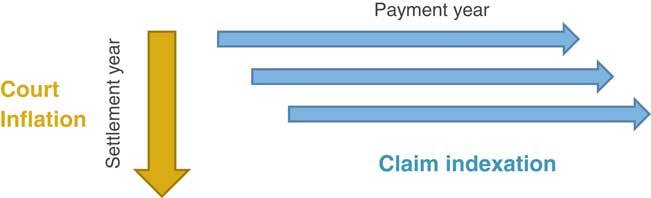

Figure 2 shows the interaction of the two types of inflation risk described above on the size of annual PPO payments.

Figure 2 Impact of inflation on Periodical Payment Order awards

4.5. Interest Rate Risk and Other Market Risks

4.5.1. Interest rate risk

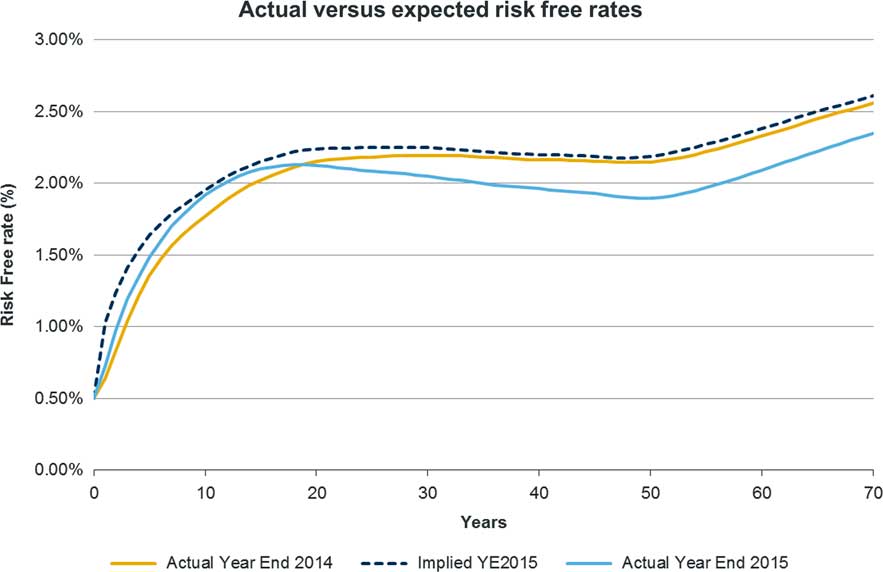

Interest rate risk refers to the risk associated with a change in the value of PPO liabilities due to changes in the level or shape of the yield curve used to value them. Given the extremely long duration of PPO liabilities, the impact of small changes in the yield curve can be extremely significant (PPOs Working Party, 2014b, page 89).

Actuarial practitioners should take time to understand the yield curve(s) used to discount PPO liabilities under the different reporting bases used by the insurer, and how these respond relative to changes in the market value of assets used to back PPO liabilities. For example, under Solvency II the choice of discount rate is largely prescribed by regulation whereas under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) there is more scope for management to apply expert judgement. This may mean that a firm’s exposure to interest rate risk manifests itself differently under different reporting bases.

Liabilities associated with younger PPO claimants may not run-off for many decades, well beyond the duration of the longest dated fixed interest assets available. This introduces re-investment risk – the uncertainty surrounding the price of assets when you need to re-invest matured assets in the future.

The asset-liability matching techniques typically used by life insurers and large pension funds to manage similar risks are more difficult to deploy for PPOs, since the cash flows are much more uncertain. This is due to the unusual inflation indices used to index future payments, and the high level of longevity risk, especially for insurers with a small number of PPOs facing high longevity volatility risk. For PPOs not yet settled, there is also the underlying insurance risk of whether the claim will settle as a PPO. Further complications may arise from technical elements of the reporting basis, such as the presence of the volatility adjustment (VA) or matching adjustment (MA) under Solvency II.

Historically, there has often been a strong correlation between movements in interest rates and movement in actual inflation rates and future inflation expectations, so actuarial practitioners should consider the extent to which interest rate risk interacts with inflation risk (see section 4.9, dependencies).

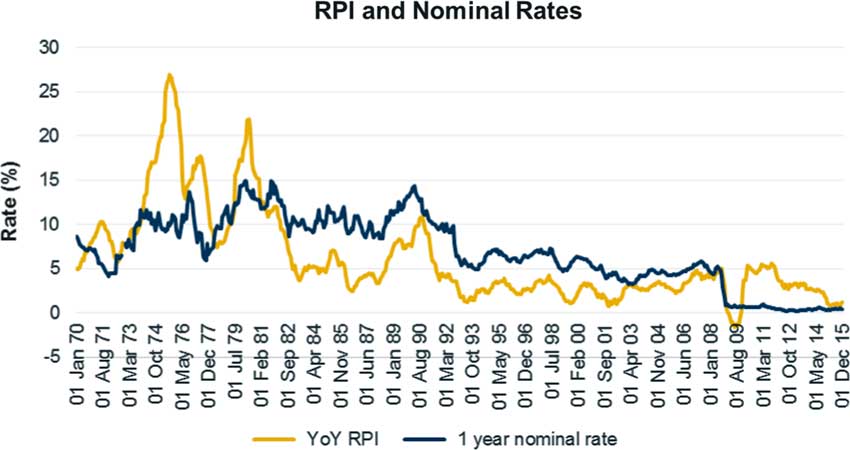

Figure 3 shows the historical trend in actual RPI and actual nominal interest rates over 1 year (Bank of England, 2016b; ONS, 2016d).

Figure 3 Relationship between inflation and interest rates; RPI, Retail Prices Index; YoY: year-on-year

4.5.2. Other market risks

While PPOs do not, in themselves, introduce additional market risks to an insurer, changes in investment strategy introduced to reflect the characteristics of PPOs have the potential to either increase exposure to existing market risks or introduce new market risks to an insurer.

For example, investments in inflation-linked assets, corporate debt, property, infrastructure debt, equities, hedge funds or derivatives may be outside the traditional investment portfolio of a general insurer. These types of investments may be selected to increase returns, but there will be a trade-off between risk and return. Utilising a more complex asset-liability management strategy may require enhanced capital modelling capabilities to be developed, or changes in a firm’s risk management framework to accommodate new sources of risk.

4.6. Variable Orders

PPOs which are variable orders give even greater uncertainty as to the amount of future payment amounts. This is because variable orders allow the annual award to be revalued to reflect changing care needs of the claimant, linked to the development or improvement of specified medical conditions.

There is very little past experience and information available (PPOs Working Party, 2015a, page 37) either to estimate the proportion of variable orders which might be triggered as a consequence of changing medical conditions or to address the average level of award increase, or decrease, resulting from a variable order being triggered. When valuing future PPOs, consideration would also be required of the proportion of future PPOs that might be variable, including whether they could be specified for different conditions or scenarios than currently specified.

Whilst it is generally anticipated that the triggering of variable orders will lead to an increase in award levels, it is possible for a variable order to result in a reduction in the award level. This would be possible in the event of a pre-specified improvement in a claimant’s medical condition, which reduces their care requirement. Furthermore, changes in award levels may indicate that the claimant’s future mortality may have also changed in the opposite direction. For example, a deterioration in a claimant’s condition triggering the variation, may increase annual payments amounts but reduce life expectancy.

4.7. Counterparty Credit Risk

Counterparty credit risk refers to the potential for an insurer to suffer financial loss due to the failure of another party to meet its obligations as they fall due. The most notable exposure is often to reinsurers, but other sources of potential exposure can arise.

4.7.1. Reinsurance default

PPOs may interact with an insurer’s reinsurance arrangements either through proportional arrangements, individual excess of loss reinsurance protection or portfolio level arrangements. Consequently, an insurer may have an expectation of material reinsurance recoveries associated with PPOs, potentially due over an extended period of time.

Even for the most highly capitalised and financially strong reinsurers, it is hard to assess the probability of default over many decades. There are major elements of PPO risks which cannot be diversified as the number of claimants increase. Whilst the risk from volatility may decrease for longevity risk, the overall risk from trends and inaccuracies in the mortality basis does not; neither does exposure to external influences on propensity; or the level of ASHE 6115. Consequently there is additional systemic risk that several reinsurers with significant PPO exposures (or other significant exposure to similar risks such as annuities) could experience financial distress at the same time. Where such reinsurers’ business is focussed on motor or casualty, the firms may have very little incentive to remain a going concern if a risk event unfolds. If there is little option to reinvigorate these businesses due to lack of diversification and no direct responsibility to the claimants, winding-up the business may be the most beneficial option for their key stakeholders except insurers. Consequently, insurers that rely heavily on reinsurance for lines exposed to PPO settlement will need to bear this in mind, as these defaults would leave them exposed in-full to the liability and its associated risks.

Whilst credit ratings provided by credit rating agencies can be used as a mechanism to help understand the credit risk of a specific reinsurer, this process relies heavily on expert judgement. There is limited empirical data on the rate of default for reinsurers over the time horizons relevant when considering PPOs.

4.7.2. Other sources of counterparty credit risk

Credit risk also has the potential to arise in scenarios where an insurer is only partially liable for meeting obligations to a PPO claimant (e.g. when it has written a co-insurance share of the original insurance policy or where liability has been apportioned between a number of parties covered by different insurance policies). In such cases, it is likely that legal advice would be required to understand the impact on the insurer’s liabilities in the event that other parties to a PPO award were to default on their obligations to the claimant. The outcome in this scenario will depend on the wordings of the individual orders as well as other relevant legal principles.

Depending on the investment strategy adopted by an insurer, it may also be exposed to counterparty credit risk associated with either physical investments or derivative contracts used to match PPO liabilities. The long duration of PPO liabilities may lead to a firm investing in assets with a longer duration than has been typical for general insurers, introducing an increased level of counterparty credit risk. In particular, investment in long-dated government or supranational debt may require an insurer to consider the possibility (even for counterparties with very strong credit ratings) of the issuers not meeting their obligations as they fall due.

4.8. Operational and Expense Risk

Operational risk refers to the risk of failure of people, processes or systems leading to an increased level of cost for an insurer, either through higher direct expenses, or regulatory censure. Expense risk refers to the risk of a firm’s future expenses being different than anticipated.

Whilst general insurers are used to considering operational and expense risk, a liability which requires payment on a regular basis over many decades is different to typical general insurance liabilities.

PPOs are still fairly new, so the chance of errors by people, processes and systems not designed for this settlement method is high. It is important to consider the differences in claims handling requirements, system requirements, data requirements, reporting requirements and actuarial modelling requirements that are introduced by PPOs. Reinsurance wordings may be complex surrounding recoveries on PPOs and therefore, require greater attention by insurers. After taking into account the current control framework, actuarial practitioners should consider any residual operational risks faced by insurers when managing PPO liabilities, and look to continually increase the robustness of the control framework.

The long-term nature of PPO liabilities means that the level of expense provisions which need to be set aside to cover on-going claims handling expenses needs to be carefully considered, alongside the risk that actual expenses differ from those projected.

4.9. Additional Considerations

4.9.1. Model and parameter risk

Model risk refers to the risk that the selected model is inappropriate, and parameter risk refers to the risk that the selected parameters are inappropriate.

It is important to be aware of the significant level of expert judgement inherent in setting assumptions for PPOs and the risk that either the parameters selected, or the models used, may not be appropriate. Given the relative immaturity of PPO modelling, and the lack of historical data on which calibrations can be based, this risk is likely to be significant for the foreseeable future.

It is therefore even more important than usual that the assumptions contained in and the outcome of any modelling undertaken is:

-

∙ carefully considered by modellers;

-

∙ robustly challenged and validated through peer review;

-

∙ well documented; and

-

∙ carefully communicated to stakeholders.

Top-down validation activity (such as scenario testing or sensitivity testing) is likely to be particularly important given the challenges with determining robust bottom-up calibrations.

Further to this, it is important that those managing PPO liabilities continually develop their technical skills and professional considerations.

4.9.2. Dependencies

With many general insurance liabilities, the impact of adverse economic scenarios (e.g. a fall in the yield curve used to discount liabilities) is not directly linked to the risk of a claim being larger than expected.

However, for PPOs, interest rate risk can compound with other risk factors to a significant degree. For example, the longer that claimants live the higher the impact is of lower than expected investment return and the lower that future investment returns are, the higher the impact is of future inflation being higher than anticipated. These are only a sample of dependencies across risks associated with PPOs.

It is possible to envisage a number of scenarios with compounded risks. This type of thought exercise is useful to help identify key risks to the business, variables that should be linked in models and may even be required by the regulator.

4.9.3. Change in risk profile over time

Another important difference to typical general insurance liabilities is that, for most firms, PPO liabilities will continue to increase until the number of deaths starts to balance the number of new cases (PPOs Working Party, 2014a). Consequently, actuarial practitioners may wish to consider both the current risk profile and the likely shape of the risk profile in years to come.

5. Data Requirements and Assumptions

5.1. Overview

As with any actuarial exercise, it is important to consider the purpose to which the model will be put to ensure its construction and parameterisation are adequate. For PPOs this is particularly important. There are many assumptions that are very uncertain at this point. This does not stop a reasonable model being created, as long as the practitioner remains focussed on the outputs required.

Evaluation of PPOs involves quantifying both settled PPOs in payment, and possible future settlements, known as “PPO IBNR”. For settled PPOs, the identity of the PPO annuitant and the terms of the award are known. Possible future settlements may come from a number of sources, claims which the insurer knows are potential PPOs, claims the insurer is not aware will be large, claims the insurer is not yet aware of and claims that will happen in the future on business the insurer has already written. Consideration will need to be given to all of these. Clearly, the less mature the claim, the less data are available to quantify it, and the more one must rely upon general statistics relevant to the class of business, judgement and the firm’s past experience. For modelling claims that are expected to arise in the future, which will always be the case in pricing, the practitioner would need to consider whether the observed distribution of PPO claimants is a fair representation of what the future claims environment might experience.

As well as making assumptions about the profile of the portfolio of PPOs to be settled, we need to make assumptions about future indexation, investment return and mortality.

Whilst there is often no prescription as to what these assumptions should be, key assumptions should be made explicit, and there should be evidence that these assumptions are reasonable. As the actual future out-turn is uncertain, it is worth flexing the assumptions to see how much this changes the expected pay-out and using these to inform the end users of the modelling. After all, in many cases, risks associated with PPOs will not be overly familiar to stakeholders beyond initial training within general insurance-focussed business, but because of their long durations they may affect the running of the company for many years in the future.

5.2. Claim Data

The quantification of known PPO claims will almost invariably be by a cash flow model. This will require:

-

∙ The payment schedule as set out by the PPO which includes the:

-

o First annual payment amount.

-

o Frequency of payment.

-

o Any planned steps to payments.

-

-

∙ Where payment amounts, steps and indexation vary by head of damage then these will need to be separated.

-

∙ The future life expectancy, determined by reference to:

-

o The age of the claimant.

-

o The sex of the claimant.

-

o The claimant’s impairment to life (usually from accompanying medical evidence and expressed as an adjusted life expectancy).

-

-

∙ The indexation method (ASHE, RPI or other referenced index).

-

∙ Any variable orders or other special features of the PPO.

-

∙ The currency payments will be made in.

-

∙ Details of any co-insurance and reinsurance applicable to the claim together with the lump-sum components and property damage elements of the claim to test if a recovery can be made.

The extent of data available will depend on the closeness of the party to the claimant, with the direct insurer handling the claim having the most information, through to reinsurers which may have less information available to them. The terms of reinsurance policies now generally require that insurers provide details of all claims identified as potential PPOs so this issue is becoming less important.

Quantification of future potential PPOs should take account of the following data:

-

∙ An exposure measure to help determine likely future numbers of PPOs.

-

∙ PPO propensity for the class and insurer, linked to that exposure.

-

∙ An indication of whether the claimant population is different to the market claimant population for the class (in order to determine likely claimant characteristics).

-

∙ Details of claims close to settlement which may settle as PPOs.

An assumption of court award inflation may need to be made separately to assumptions on indexing the annual payments if models project PPOs that commence in the future. PPOs are generally linked to indices and surveys once an award has been made, whereas the initial level of awards has other pressures such as changing attitudes of the courts towards the necessary level of care.

5.3. Indexation of Annual Amounts

PPOs are typically inflation linked to provide the required level of protection intended at settlement. Often the reference to index payments is a percentile of the ASHE 6115 sub-code, as this relates specifically to wage inflation of care workers in the United Kingdom. Inflation linking using ASHE 6115 has led to both increases and decreases in the payments over the years since PPOs were introduced from a mixture of inflation and deflation of care workers’ wages. The common use of this index, as opposed to RPI, gives additional complexity. There have been some orders that give periodical payments under more than one head of damages, with the different sections being linked to different indices. There have been investments linked to RPI available for some time, allowing the possibility of using the assets to value the liability directly using economic scenario generators (ESGs). There are no known investments that can be used to obtain a price for ASHE from securities data at the time of writing. It should be noted that orders are indexed at different percentiles and that ASHE 6115 is not the only reference for indexing, reducing the likelihood of there being an asset match in the future.

Therefore, forecasts of the expected future inflation will need to be made, which is not a straightforward exercise. Whilst some forecasts for wage inflation do exist these are not necessarily in line with ASHE 6115. In addition, the link between the indexation and the investment return assumption needs to be considered so the assumptions are consistent and coherent. A failure to treat investment return and inflation consistently will seriously jeopardise the robustness of any model output. A simple example of not being consistent would be excluding a period of unusual inflation but not investment returns over the same period if using historical data to set assumptions.

The indexation assumption is an important variable. Ignoring reinsurance, it defines the future cash flows in nominal terms, which is important for cash flow and general business planning. Considering reinsurance, where treaties are indexed, the inflation will affect the level of coverage provided in nominal terms. Consequently for direct insurers a robust projection is needed for an accurate determination of reassurance assets, and therefore the net of reinsurance balance sheet position. For reinsurers, it is obvious this assumption will materially affect their reserve value.

The purpose of the model may restrict or guide the indexation assumption, because of influences from both external factors, such as Solvency II, and internal factors which may include the company’s accounting policies.

If a term structure-dependant investment assumption is chosen, perhaps because of a portfolio of gilts over varying terms, then a term structure-dependent inflation assumption should also be selected.

A formal assumption linking inflation with investment returns will be needed for any model that is stochastic; however, it is important to note that we are not aware of any investment product available to match this inflationary measure precisely.

Regardless of the basis, the practitioner should test the reasonableness of the assumption used. The reasonableness can be tested by looking at historical inflation levels, current market-consistent expectations of future inflation and future economic reasoning in respect of the projected inflation rate. These are considered below, and along with those for investment returns were published at early stages in the 2015 CIGI presentation (PPOs Working Party, 2015b).

5.3.1. Historical analysis

The reliability of historical analysis is limited by the volume of data, given the relatively young age of the ASHE survey, and that it is produced only annually.

This limitation may be addressed by considering a less volatile, but closely linked, inflation index. For example, the Health and Social Work component of the Average Weekly Earnings index could be considered. This has the benefit of being compiled from millions of data returns rather than just thousands, which smooth volatility as well as benefitting from a longer history. Adopting this approach gives the breadth of data missing from the ASHE series, but if used for stochastic outputs, a VA will have to be made to allow for additional volatility if the indexation method is more volatile than the reference index.

This is not the only comparison that can be made. The difference between ASHE 6115 and RPI or interest rates can also be considered. Obviously, it is valuable only if the comparison helps to explain and project trends with greater confidence.

Any evaluation of past inflation needs to incorporate an understanding of any atypical periods within the data set, as well as an understanding of how investment returns responded during this time to ensure that the real rate of return is not distorted. As with any historical information analysis, judgement is also required on what period is relevant to estimating future inflation.

5.3.2. Market-consistent views

RPI-linked investments provide a common source of information which is already used to parameterise ESGs to give a view of future inflation by term. This is directly relevant for the smaller proportion of PPO claims linked to RPI but further consideration is needed for those associated with other indices.

For these cases, the RPI-based output must then be transformed to give an appropriate assumption for the indexation of each individual PPO. Whilst it is commonly ASHE 6115 which is used, it may also be other sub-groups of ASHE, as well as different percentiles of the particular survey. Therefore, further consideration may be required on whether or not there is a need to consider more than just this popular measure. This decision will need to be based upon the materiality of the existing inflation profile of the companies’ PPOs, as well as any future projection.