The Chairman (Mr A. H. Watson, F.F.A.): Welcome to tonight’s sessional research event, which is on Actuarial methods: are we serving the public interest?

This debate was born out of a conversation that Hilary Salt and I had a couple of months ago when we were both concerned that scheme funding seemed to be rarely debated within the profession.

Then I saw the famous photograph of the university lecturer on strike with a placard bearing the memorable slogan, “Value pensions using stochastic models not actuarial discounting rules”.

I thought: What would we say to refute that? I would warn you, though, that we are not here to debate the Universities Superannuation Scheme per se, although it may come up, but funding in general and scheme-specific funding in particular.

I hope you find it relevant and thought-provoking.

Turning to our thought-provokers, both Hilary Salt and Donald Duval have prepared the presentations for this evening.

Andrew Cairns does not have a presentation but is happy to give some opening remarks.

Once they have completed that, we will be able to throw the meeting open the floor for your own contributions.

With that, I should like to introduce our panel for the evening.

Firstly, we have Hilary Salt. Hilary is a founder of First Actuarial LLP and combines national executive responsibilities in the business with running the Manchester office. Hilary’s client work covers traditional actuarial consultancy, including acting as a scheme actuary and advising sponsoring employers. She also works with trade unions, where she assists in collective-bargaining situations and advises on the pension schemes run by trade unions themselves.

She has worked extensively with the Communication Workers Union, devising the ground-breaking collective defined contributions (CDC) proposal which ended its dispute with Royal Mail. She has also advised the University and College Union (UCU) on alternative approaches to the valuation of the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS). Hilary has also provided policy advice to a number of organisations and is the independent actuarial adviser to the National Health Service (NHS) pension scheme’s scheme advisory board.

She is a member of the Council of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA) and she has written several published articles and is a regular speaker at conferences.

Ms H. Salt, F.I.A.: I wanted to start with what I think will be a non-contentious statement that pensions are a public good and our providing them, or assisting to provide them, is part of our public interest duty.

We need to provide people with an income for life. A phrase that the Communication Workers Union was keen on was a “wage in retirement”.

People who have been used to an ongoing income during their employment need an income in retirement. That should not just be for those with that golden ticket of a legacy DB scheme, but for past, present and future generations of workers.

We need to provide that in a cost-efficient way and I would say the biggest and the most important way to provide pensions efficiently is to have open schemes. If you have open schemes, because money is fungible, you can use your income to pay your pensioners. That means you save the cost of investing the money coming in, and you save the cost of dis-investing the money coming out. It also means that you do not need to be worried about the day-to-day value of the assets, so you can invest in assets that are illiquid or have volatile day-to-day values because you do not need to sell assets every day to pay pensions.

I also think that it is not unreasonable for employers contributing significantly to schemes to want some payback for that investment, typically to be able to use the scheme to recruit, retain and encourage return and allow people to retire.

Many employers are grumbling at the moment about the skill shortage, about the inability to keep people – “Millennials do not stay in employment”, they say. Clearly one way to encourage them to do that would be to provide a good DB scheme, and we should be able to help employers to use pensions as a tool to help them with those problems.

That is my first contention.

I would say that we are not delivering that. What we are delivering is something that I think is shoddy. The DC schemes that most employees have been enrolled into do not provide a pension at all, just a lump sum which is difficult to convert efficiently into a wage in retirement.

The potentially efficient DB schemes we have are being run at maximum inefficiency. They are closed so there is no fungibility bonus. They are itching to move into the lowest yielding assets, ones that guarantee a negative rate of return, or they are looking to buy out.

“Nobody buys annuities any more”, people say, “except for those DB schemes that are doing precisely that”.

As a final insult, many of them are tipped into the PPF, the sovereign wealth fund that we might have had had we not decided to invest it utterly unproductively. By the way, the PPF is not just funded by levies, it is also funded by the assets of the schemes entering it and by the monies produced by members giving up benefits when they enter it.

I think there is intragenerational inequity. One example is when employers have made commitments to pay discretionary pension increases. Members had a valid and realistic expectation of those increases when they reached retirement and instead we have employers using any surplus in the scheme to de-risk it to protect their balance sheets, rather than to meet those member expectations. We have created a crisis in public confidence, snatching defeat from the jaws of victory at a time when pensions are better protected than they have ever been.

Instead of reassuring members that they are protected by the PPF, we tell them that to end up there is a disaster when in reality for most workers a DB scheme and then entry to the PPF is significantly better than a lifetime in an inadequate DC arrangement. We have created a headache for employers who are dealing with a two or three tier workforce, unable to keep staff and unable to get rid of staff who reach retirement with an inadequate DC pot.

So how have pensions become a massive problem for employers and employees? We must look to actuarial advice as part of the answer. I want to examine a few pieces of evidence to back up that claim.

The regulator’s integrated risk management diagram says everything affects everything else. It is horribly complicated. I dislike this diagram because in effect it just says it is all too difficult, so you cannot do anything except, of course, to buy more bonds – the regulator’s answer to everything. I am unconvinced that the employer covenant has any relevance to this. But as the regulator is keen on it, I thought I had better give it some attention. But let us assume that we can use the employer’s covenant to assess the appetite for risk, to assess an appropriate investment strategy, and once we have our investment strategy, let us use it to establish a prudent return on our assets and use that to set a funding basis.

That is to me the right way, but all too often you see exactly the opposite. The actuary says, “I am using a gilts-based funding basis” and you then say, “Well, of course, to reduce volatility against that gilts-based funding basis, you need to buy more gilts”. So you do that, all the while maximising the cost of the scheme, undermining the strength of the employer covenant, forcing unnecessary scheme closures and maximising the risk of benefits not being paid in full.

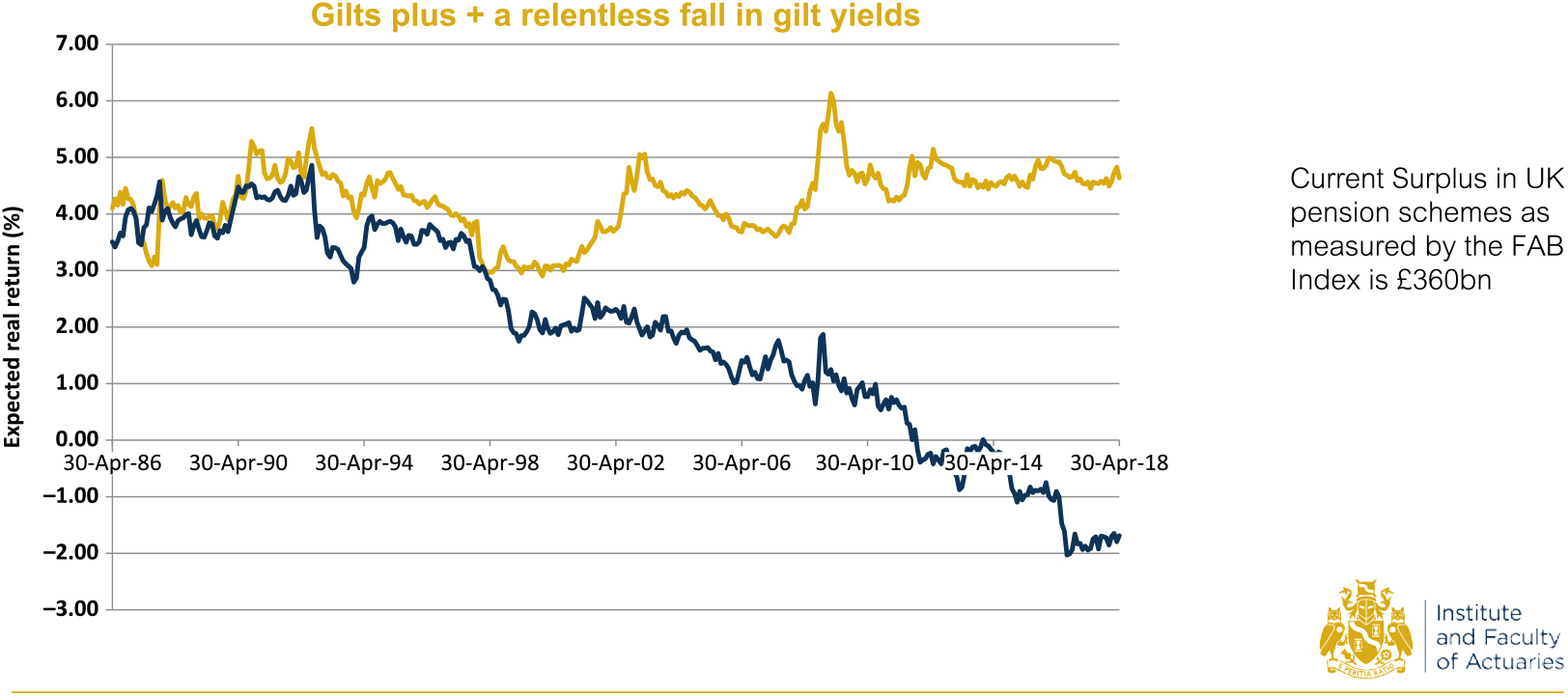

That was my first piece of evidence. My next piece of evidence is gilts plus funding methodologies (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Expected real returns.

The blue line shows the sustained falling gilt yields with a pronounced new phase starting after the financial crash in 2008, followed by unrelenting quantitative easing which pushes the yield curve down and down and down.

The gold line is the expected return on UK equities, established starting from a dividend yield, a quantifiable number. Obviously, if you try to assess the return on equities in that gold line by adding a fixed amount to the blue line, you get further and further away from a sensible answer. You introduce more and more prudence into your valuation basis.

We are currently a society that is negative about risk. Risk is always seen as a bad thing. That was never the case in the past.

But as well as being risk-averse, we have also moved from deterministic attitudes to risk, to probabilistic attitudes to risk, to “possibilistic” attitudes to risk, those unknown unknowns.

That kind of social change has been mirrored in our professional work, moving from deterministic models to stochastic models. I do not think that the placard that Alan [Watson] mentioned is right.

The problem is that if you model 10,000 versions of the future, you remove the space for actuarial judgements. You also remove the possibility of thinking through what must happen for result 3,761 to come about. The fact that the model produces it does not mean that that is an outcome that is plausible. We should be encouraging people to make sure that they can plausibly say why any of those outcomes is possible. I do not think “it is mathematically possible” is a good enough answer. It is the phrase you hear only about stochastic models – and you hear it towards the end of the football season. These are the only two times when people want to believe in those outcomes.

We have a lazy use of the word “risk”. When we say “risk”, we generally mean volatility or the risk of asking an employer for more money, the risk of having to close a scheme, the risk of having to cut benefits, the risk of not making discretionary benefit increases, the risk of not paying benefits in full or the risk of members losing their livelihoods. All those risks are ignored and we concentrate on that one risk that we think is important.

That was my penultimate piece of evidence.

Finally, we need to be absolutely clear about what the legal requirements are. These are prudent assumptions, discount rates based on the yield on assets held or on bonds, and mortality and demographic assumptions to be chosen prudently.

Everything else is a regulator addition, a regulator incursion, and I would say that while those things emanate from the regulator, they are incursions that are policed by the professional trustees who do what the regulator says, whether it is the right thing to do or not. Those regulator additions include a push towards gilts-plus. “We are not a gilts-plus regulator” they say, and then they turn around to me in their pro-active engagement in a scheme and say, “But you are assuming a return on top of gilts of this much”. “But I thought you were not a gilts-plus regulator.” It does not quite seem to work.

They focus on employers’ covenants and often they will not believe an employer’s covenant that has been assessed by trustees. They produce no evidence for their disbelief.

They are pushed towards solvency, which is the opposite to scheme-specific funding, requiring everybody to fund at full solvency. There is no requirement to do that.

Most shamefully, they are driving good lay trustees out of the trustee boards.

Let us remind ourselves: a fixed (and democratically-agreed) position is that schemes do not need to be funded to buy-out, and, in the event of employer insolvency, members can rely on the PPF, and we should stop forgetting about that.

I cannot resist that Michael Gove quotation in full: “I think the people in this country have had enough of experts from organisations with acronyms saying that what they know is best and getting it consistently wrong”. Yes, we have had enough of that.

During the USS dispute, the phrase “revise and re-submit” was trending on Twitter. Many academics were saying that what the USS trustees needed to do with their valuation was to revise and resubmit.

I would propose that, as a profession, we need to revise and resubmit better funding advice, trying to keep schemes open, building member confidence, stop behaving as if the PPF does not exist, and, finally, re-democratise schemes, rebuild Britain and rediscover pensions.

The Chairman: Donald Duval is our next speaker. Donald is a partner at Aon, with responsibility for professional standards, thought leadership and innovation. He is a regular speaker at pensions conferences and has been president of the Society of Pension Consultants, a Member of Council of the Institute of Actuaries and a member of the main committee of the Association of Consulting Actuaries.

Donald has also been Australian Government Actuary and has advised on pension reform and regulation in Hungary, Zimbabwe, Slovenia, the Czech Republic and South Korea. His main professional interest is in the management of the overall financial position of pension funds. This requires a consideration of both the assets and the liabilities – their dynamics, risks and opportunities.

Mr D. B. Duval, F.I.A.: I have prepared a few things to say, but I also was thinking that, so far as I can, I might comment on what Hilary has said. I agree with most of it. Where I think I part company to some extent is on the causes and reasons.

That pension is a public good I would certainly agree with. The system seems to be increasingly failing. This is, I think, also an issue, and it is an issue with which we, as the actuarial profession, should engage more than we are, which is not to suggest that we are unengaged with it.

The way I was going to approach this was by looking at the outlook for investment. Fundamentally, whatever the structure of pensions, there are only two types of money. There are contributions paid by employers and workers, and there is investment return. Most of the arguments come back to the position on investment return.

I want to look at what happened in the investment world and what the outlook is for that. Where can you invest your pensions? Where can you invest your money?

Government bond yields for many of the major countries, the US, UK, France and Germany, are down substantially.

If you want to invest money for the next 10 years in government bonds, you can be certain you will earn a lot less than you would have done if you had invested that money 10 years ago or before then. The US is probably the best. In the US you are only earning 1.75% per annum less than you were; everywhere else the yields have fallen by something like 3.5% over that 10-year period.

Therefore, any money you choose to invest in government bonds has a massive impact on the amount available to pay pensions.

If you invest in corporate bonds, the position is much the same: slightly greater divergence between the US at the top and the European countries at the bottom with the UK in the middle; but, nonetheless, very substantial falls of a similar amount. Fundamentally, investing money now, if you invest in gilts or corporate bonds, you will be getting much lower returns.

The position with equities is, if anything, worse. Expectations of future equity returns have had a downward shape. The exact number will depend on the period and how long the equity holding period is expected to be. I will come back to what is sitting behind the equities in a moment because these are fundamentally assumptions produced by experts and therefore, as Hilary has correctly pointed out, it is reasonable to question them.

You can also invest, if you want to take greater risk, in high-yield bonds. The additional spread you get over high yields over other bonds, are investment-grade. Again, very substantially down.

Most managers these days will tell you the illiquidity premium is zero or possibly negative. There is a complexity premium which is obvious when you see the amount of complicated structures that are being created. If you can see through those, there is a complexity premium. Those structures are primarily aimed at producing highly complex illiquid products to disguise the risks sitting within them.

The UK government, by the way, participated in that in the way it did its student loan book when it sold that off.

If we look in more detail at equities, we have the price of equities to the book value of equities. Well over half the global stock market at the moment is at an all-time high on price-to-book ratios.

There is an argument that, with modern investments, companies today do not need to invest as much as they used to and therefore book values do not need to be as great. But, fundamentally, technology companies are created with fairly modest investments, so there is an argument that price-to-book may be on a long-term trend rise.

We have seen good returns on equities over a substantial period. But those returns have been driven, to a substantial extent, by improvement in profitability for relatively constant sales. Companies have been successful at squeezing profits. They have closed their defined benefit schemes and replaced them with poorer DC schemes.

More particularly, they have squeezed wages, which would be more effective, and they have borrowed money at very low rates of interest.

But however far you manage to squeeze costs, that fundamentally cannot go on forever. The only thing that will enable you to get continued growth out of corporate profits is growth in sales. So, although price-earnings ratios are commonly used, price-to-sales ratio is the better measure when you are looking at the return you can expect to get from the companies in which you invest.

That is now at an all-time high in the US market.

When we are buying equities we are buying shares in companies which, in order to get any kind of reasonable measure of return, have to perform, have to produce earnings, have to produce sales growth of a type that is difficult to imagine and certainly never been seen before and/or effectively crush costs massively on the trajectory that they have already been on. Both of those seem extremely unlikely.

I should be the clear that I am not predicting a crash in the equity market. What I am saying is that the returns you will achieve by buying and holding equities will not be at anything like the levels that we used to predict or that we have recently seen.

The implications are quite significant because, in the recent past, if you have had assets, provided they were not assets in cash, you have done very well, but if you have not had assets but are going to be investing in future you will have done poorly.

In fact, basically the general rule of investment over the last 10 or 15 years has been to invest alongside rich people, and not to invest alongside poor people. That is a general rule of investment: invest alongside the powerful. What is mildly surprising is that democracies are in fact operating as plutocracies, not democracies, now. The implications for this are not just intergenerational.

If you look at the projected pension that two DC members might get, the two members are much the same age but one of them has a substantial accumulated balance. The other one has almost nothing. This is only over a 3-year period. Over a longer period the impact is much more dramatic.

The latter one has still got almost all their investment to do, their expected pension has fallen by over 5% over a mere 3-year period. Over a 10-year period, it is far bigger than that. The projected pension for the one who has lots of accumulated assets has gone up substantially. This is the fundamental issue currently behind almost any kind of long-term benefit provision, whether provided through defined benefit or through defined contribution. But the returns people are likely to get from investments from the position now and from future investments are very low. Therefore, to produce any kind of decent outcome, whether a promised outcome through DB, or a desired outcome through DC, you need many more contributions than people have been accustomed to paying or that people want to pay.

On the other hand, for people who have accumulated assets and have benefited from recent performance, their position is that they have benefited from significant wealth transfer to them. They will be assured of a comfortable position.

That, I think, is the basic problem behind all the pension debates about funding rates and is more important than how you produce your discount rate or the like. However you produce it, you are still going to have the problem that you are trying to represent where future money is invested and future money is not going to earn much by way of return.

The Chairman: Andrew Cairns, who is going to speak now, is a Professor at Heriot-Watt University and director of the Actuarial Research Centre (ARC) of the IFoA. He is well known both in the UK and internationally for his research in financial risk management for pension plans and life insurers. In recent years, he has been working on the modelling of longevity risk – how it can be modelled, measured and priced, and how it can be transferred to the financial markets.

He is an active member of the UK and international actuarial profession, including acting as editor of the ASTIN Bulletin: The Journal of the IAA, from 1996 until 2017. In 2016 he was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Prof A. J. G. Cairns, F.F.A.: I declare that I am a member of the USS so I am interested in how things are going to develop over the next months and years. Of course, possibly some of my remarks might be coloured by that fact. But I will talk in greater generalities.

I am not a pensions actuary; I am an academic with interests that are partly in the pensions area and, more specifically, in longevity risk.

I am going to defer in the discussion to my colleagues on many points in terms of the regulatory side of things, for example. But what I might do in these few introductory remarks is to start bringing up perhaps a fresh perspective, occasionally provocative, and not necessarily suggestions that I myself believe, but I think that they are things that might be worth talking about.

I will briefly comment on point estimates, prudence, etc. For a pension valuation, we need eventually to come up with our point estimates. But, of course, this is placing too much emphasis on one number in what can be a very wide range of outcomes. Should we be throwing out that useful extra information?

These point estimates might well be based on a variety of assumptions that require some element of subjectivity.

Prudence goes into a valuation but it relates to the strength of the sponsor covenant, but to me it feels like there is – and I have always thought this, not just at the current point in time – too much mystery surrounding how the resulting margins are set. For example, how does the margin in the discount rate relate to sponsors with differing strengths of covenant or different levels of funding? What does it mean to lower the discount rate by 0.5% relative to uncertainties in the balance sheet now and in the future, and the probability that the sponsor becomes insolvent?

This is the provocative part: perhaps we should be tackling prudence in a different way. That could be, say, starting from a best estimate of the technical reserve rather than the one that has multiple levels of prudence built in. But then prudence is reflected in faster deficit reduction for weaker sponsors or perhaps a variance of what is effectively the PPF levy that charges a market rate to insure against the difference between the solvency liability or buyouts and the current asset values in the event of the insolvency of the sponsor.

What is the regulatory balance between past and future benefits? In my view, there is too much emphasis on protecting accrued benefits at the expense of future accrual. The overall prospects for a comfortable retirement of anybody who is a member of a DB plan are being damaged by excessive regulation rather than being enhanced.

Why is that? I have three examples. When I started as an actuarial trainee a long time ago, pension scheme trustees had a lot of discretion over benefits that were going to be paid. But then there was a series of well-intentioned changes in pensions law and regulations. These were intended to provide protection to pension scheme members.

But what they did was to protect accrued benefits only. Also at the same time, it caused many sponsors to close their DB schemes to future accrual and to switch to DC with typically much lower contribution rates passing on risk and lower pensions.

Well-intentioned legislation has resulted in worse benefits for a large proportion of the DB membership, rather than better.

Other factors come into play, such as lower yields, which has already been pointed out, and falling mortality, but the burden of regulation has played its part in the decline of DB.

The second example is the March 2018 pensions White Paper. To quote from that, “our ambition is to maintain confidence in defined benefit pensions by increasing the protection of members’ benefits”.

This to me sounds like more of the same. The issue here is that, because of the government’s determination to root out a small number of bad eggs at all costs, all of us must suffer through increased chances of benefit cuts or DB closure. At what point do the costs outweigh the benefits in terms of regulation?

The third example is that, compared to insurance, pension schemes have always had the advantage of flexibility over the contribution rates. If experience turns out to be worse than anticipated, you can pay more later. But then of course prudence creeps in. More prudence forces up the short-term contributions because of our reduction in the yields for discounting liabilities, and then of course that frightens the sponsors of these pension plans. For the sponsors who are weaker and must have greater levels of prudence, it scares them even more. And, again, they close the scheme. So members lose out again.

My last point is to talk about risk appetite, which has not yet been mentioned. This needs to have a place in the discussions. How many pension schemes have a well-formulated risk appetite statement? Many will have an objective somewhere in their documents that talks about how they want to end up at some very low-risk investment strategy at some point in the future. That has been questioned by one of the other panellists. But what is their risk appetite between now and then? That is often vaguer.

It cannot be zero, because they are still taking risks. They are still investing in equities, etc. Can we as a profession develop a risk appetite framework, perhaps in a stochastic setting, that balances the aspirations of the members, including future benefits accrual, alongside reasonable year-to-year regulatory requirements?

The Chairman: The discussion is open to the floor. You may want to ask questions of the panel or make your own views known.

Mr J. Hamilton (opening the discussion): I am a trustee and basically look after pensions. The most important macroeconomic issue affecting the country is the allocation of £3 trillion of DB investment money. This profession must understand what is happening to the economy.

If we follow the flight path of all the pension schemes over the next 10–15 years, we all end up in gilts. Can we stop using word “gilts” and call it “future taxation”?

We are going to take all the money that we used to invest in global equities and invest it in future taxation. Future taxation is paid by future people. Part of the issue is most of the rules are made up by 50-year-old white people who are trying to capture a section, an allocation, of wealth. If you think that you are making your wealth secure, you are not.

The problem is the models were created on a scheme by scheme basis when the allocation of the nation’s wealth to pensions was minuscule. But the allocation of the nation’s wealth to pensions now is massive so we need to challenge the model.

What do we need to invest in to pay pensions? What we must invest in is future people. We are not investing in future people.

If you are a bus driver, a train driver or a nurse, you have no idea. I have spoken to finance directors who have no idea of pensions investments.

If we do one thing, let us not describe “gilts” as being risk-free.

This nation is transferring £3 trillion of private investment in equities and bonds and infrastructure over the past 15 years into gilts and gilts are future taxation. All of those assets will still be owned by somebody. They will be owned by the independently wealthy. They will not be owned by the pension schemes.

To fix this, let us produce a different model, a model that invests in the future.

We need to move away from the notion that gilts are risk-free. Do we really think investing £3 trillion more in UK gilts is risk-free? It is not.

It is gloomy if you are under 50. If you are over 50, you have a sizeable chunk of wealth and the regulations are saying put even more money into that sizeable chunk of wealth. That will be great for the city: more investment and more spread off the top.

It is tough going for the young – those future people we need to pay our pensions. They will not pay. There will be a social revolution because they will not pay council tax, they do not have a house; they do not have a pension.

If you really want to secure your pension, invest in the future, invest in your children and invest in the country.

The Chairman: May I take another observation? We will go back to the panel at some point, but is there another observation, or a question?

Mr A. C. Martin, F.F.A.: May I start by thanking the profession for convening the debate today on actuarial methods? May I also thank the profession for the bulletins last year on the subject of intergenerational fairness? I will come back to that.

In line with earlier comments, I should declare an interest – not a conflict of interest but an interest – in advising on the USS pension valuation through my work.

I think valuation methods are secondary to valuation assumptions. In particular, in relation to the USS and the wider public sector, may I say how some public servants in school teaching and many university lecturers receive benefits in the Teachers Pension Scheme on the assumption of a future discount rate of Consumer Price Index (CPI) plus 2.8%? Please remember 2.8%. These benefits are, however, unfunded and there is no regulatory scrutiny involved.

In another part of the public sector, employees participating in the Local Government Pension Scheme will typically have benefit valuations based on a discount rate of CPI plus 2.2%, slightly lower but closer to 2.8% when an assessment is made of future service contribution rates.

These benefits are funded – £300 bn–£400 bn in good long-term investments. But, again, no regulatory scrutiny, albeit some monitoring by the Government Actuary.

Thirdly, university lecturers in the USS receive benefits costed on a discount rate of approximately gilts plus 1.7%, another step down. These benefits are funded prudently and are scrutinised by the Pensions Regulator and that scrutiny includes consideration of self-sufficiency just in case society does not need higher education in future decades!

The arithmetic is quite simply that lower discount rates equate to bigger deficits, higher contributions and lower benefits, later retirement, perhaps even inadequate revaluation of CARE (career average revalued earnings) benefits or some combination thereof.

Therefore, USS members are being penalised not so much by the valuation method but because of the valuation assumptions, advanced funding, private sector prudence and consideration of self-sufficiency.

So in the wider world, where public sector employees might all expect to be treated equally in respect of defined benefit (DB) pension promises, some are more equal than others.

Because the term “public interest” was included in the title, I feel one key assumption underlying unfunded public sector pensions needs to be mentioned because I think the promised benefits are unsustainable.

Our collective unfunded public sector DB liabilities for teachers, police, fire, NHS workers, etc, come to around £1.5 trillion, one that conveniently, given the last speaker, is not far away from the nation’s total gilt issuance. Both are repaid from future taxation.

These public sector-unfunded defined benefit promises are made on the back of an actuarial assumption, a discount rate which has the acronym of SCAPE (Superannuation Contributions Adjusted for Past Experience) set at 2.8% above CPI. That, in turn, is set by reference to gross domestic product, GDP.

GDP is not anywhere near 2.8% at the moment. It has not been for years and I would suggest might not be for the immediate future. Indeed, looking back, that assumption, which future tax payers are underwriting, has only been achieved once since the early 1980s.

I therefore suggest that actuaries, society in general and let us also include politicians and current taxpayers, have been a party to a massive intergenerational transfer of pension debt to Generation Z.

I think we should be more aware that this assumption totally dwarfs anything that comes out of actuarial methods. Therefore, I suggest you challenge your local MP as to why he or she is guaranteeing future austerity; that is the significance of the assumption.

In the public interest, I think the pensions’ profession and the Financial Reporting Council (FRC)should challenge the Treasury and others in Government on this other national debt. Conventional gilts were mentioned by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, when he was aiming to reduce the effects of inflation, but not on the other index-linked liability of unfunded pension promises.

We, perhaps, also should apologise to our children and grandchildren for the burden that we currently have left them to pay.

Finally, on a slightly lighter note, I suggest that we might give the Pensions Regulator greater involvement in scrutinising these assumptions – for consistency and future scrutiny across all funded and unfunded public and private DB benefits. They do not currently have that remit. If they did get that remit, perhaps they might like to interview the Treasury or even the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) Select Committee on their current management or, I would suggest, potential mismanagement, of this absolutely massive intergenerational transfer.

Ms V. A. Bingle, F.I.A.: I work at Alpha Financial Markets Consulting and have spent the past 6 years as an investment actuary.

One of the themes that have come up in several of the talks has been around the shift of responsibility for savings from collective schemes onto the individual.

Something we are good at as actuaries is thinking of our product or the area we work in: “I am an investment actuary, or I am a pensions actuary or an insurance actuary”. To better serve the public interest, should we, as a profession, shift our mindset away from products in a silo and towards a mindset of savings for the individual, taking into account not just DC pensions, but the savings choices that individuals nowadays have? Particularly interesting for my generation is whether you decide to invest in housing as a genuine alternative to pension saving.

The Chairman: Do we have some comments from the panel, now?

Ms Salt: First, the issue around “there are a few bad eggs”; I would challenge that. My view is that both Carillion and British Home Stores (BHS) are good news pension stories because members, even before the intervention in BHS, could rely on benefits in the PPF, and those benefits in the PPF might be slightly less than they were expecting, but for most people not much less, particularly taking into account the PPF’s early retirement and commutation factors.

I heard on the radio, at the time of BHS, two shopworkers being interviewed. They were utterly aghast because what they were hearing in the press all the time was that they had lost their pensions. They had not. They had a slight reduction in their pensions because they had been protected by the PPF – a massive gain for the pensions world, fought for and won by the trade union movement. It is about time we started acting as if the PPF is there, rather than acting as if the PPF is not there.

We need to recognise the sharp conflicts of interest at the regulator, and there is a real divergence between the regulator’s interests and pension scheme trustees’ interests.

Pension scheme trustees are interested, rightly, in making sure that they pay the benefits in full long term but they are also interested in having continuing benefits. If their scheme is currently open, they should be trying to keep it that way.

Just to come back to the public interest point, if you want to build a house you need to hire a construction company. At the moment in the pensions world we only have demolition companies. That is our failing. We need to have a form of regulation that allows schemes to remain open. We need to be able to provide the same levels of decent pension provision for future generations as well as past.

I think it is important that, when we talk about pensioners and intergenerational shifts, there is no difference between funded and unfunded pension schemes because pensioners do not save food or health care. They save the token that they will use to buy those things from a future generation.

The terms on which they buy those things will be set by that future generation.

If you have an unfunded pension scheme, a public service pension scheme, future generations could effectively tax most of that away from you. If they want to do that, that will be a democratic decision made by that future generation.

I disagree with much of what Alan [Martin] said. I think it misunderstands the way in which future generations of pensioners buy from future generations of workers.

The best way to make that transaction better is to make the pie bigger, and the best way to make the pie bigger is by investing productively in the economy and by solving the productivity puzzle. From everything Donald [Duval] said about low levels of return, it always seems that we cannot solve the productivity puzzle. I agree if we do not solve it, we are in deep trouble.

I believe that we can solve it, and I believe that we need to solve it by doing things like letting unproductive companies go out of business.

We have a very low level of bankruptcies in the country at the moment. We need to see that rise. One of the problems with MPs is that they do not like to see anybody lose anything. Some of the content of the White Paper is about more regulatory intervention to restructure businesses to make sure that pension schemes do not go under.

Let us not restructure those businesses. Let them go. We can build thriving new industries which are not just financial services businesses, but businesses that grow the pie and allow our young people to have a lot more to look forward to in future.

I agree that ordinary working people should not need to engage more with their pensions; they should not need to be educated more about pensions. They should just have a scheme that works.

I do not need to know how my car works. Nobody tells me I need to engage more with my car. I take it to a garage to get the mechanics to fix it and it is back on the road again. We need to be able to find that same public service to people who need pensions.

The Chairman: Any other contributions from the panel?

Mr Duval: Yes. I must admit, Hilary, I did not expect you to be describing Carillion and BHS management as “not bad eggs”. But I understand the point that you are making about the members’ benefits.

I am not too worried about the flight to gilts. Firstly, because it is not as big as people think. For example, when you do buyouts, there is usually a move away from gilts not towards them because gilts are normally paid to the insurer and the insurer does not invest wholly in gilts.

Secondly, the gilt market has a substantial participation overseas which means that I do not believe it is mispriced. If it were hugely mispriced because of the UK demand, the overseas investors would flee, and they have not done so.

As long as we have an open market, that is reasonably satisfactory.

I am not going to comment on any of the specifics of the public sector schemes, but I have one comment in relation to the Pensions Regulator and the concern in general about self-sufficiency: most pension schemes last significantly longer than the employers that set them up. That is by no means true of all, but it is true of the majority. That is why that is a concern that any Pensions Regulator must consider.

On the engagement issue, Hilary, I agree with you that the emphasis on trying to make people understand things as opposed to having something that just works is going in the wrong direction and we should say so. But at the moment, firstly, we have that problem; secondly, the issue identified is that what people need to work out is the entirety of their financial position, the housing, the pensions decision, etc, and saying we need to educate on all these separately makes it impossible.

As for the issue of how actuaries engage with individuals, we built our skills on collectivising difficult problems and therefore enabling us to apply more brainpower and more calculations. The only reason we do valuations every 3 years is because the calculation effort was so infernally difficult. Any sensible regulatory structure now would not be built round the valuation cycle.

I think that is a difficult problem and one well worth trying to solve. There are a small number of actuaries around the world in various countries trying to solve it. I am aware of some in Australia. I think that they are making progress. I have seen some effective descriptions about what a reasonable level of benefit means in the terms of how you can live, like how many holidays a year you can have and how often can you eat out – terms that are meaningful – then doing the description of what it means financially, with analysis behind the scenes. It is difficult but worthwhile.

Prof Cairns: I agree with the first comment about the macroeconomic approach. I think that we are currently in a situation where the DWP and associated bodies micromanage the pensions side of things in isolation from everything else that is going on. Therefore, a response to that is to make sure that the Government itself takes a more macroeconomic approach and decides what we want. How do we want this money to be invested and to be productive for the economy? And then it can essentially manage the pensions system and regulate it in a way that encourages, rather than punishes, risk-taking.

For example, there are the bigger pension plans such as the USS. They are able, at least while DB stays, to invest in illiquid investments and infrastructure. If we ended up in a position with no DB schemes, then where is the money going to come from for the big infrastructure projects?

I agree that the PPF is good. We just need to make sure that the levies get paid at the right level.

Dr C. Morelli: I should declare an interest here. Not only am I a member of the USS, I am also a member of the University Colleges Union (UCU) and one of the negotiators for UCU members on the USS joint negotiating committee. I was involved in negotiations about this dispute.

I should like to make a few points, not about the USS, but generally. The first thing is that I think the dispute has created a clear indication that there is an overwhelming support for continuation of a pension scheme that gives secure benefits.

In terms of the discussion about educating people, the university employees now are, I can tell you, extremely well-educated on pension schemes. They have given resounding views on this, without a shadow of a doubt.

A general view, much wider than in higher education, is that there is a real demand for security in retirement and a demand for certainty about what is happening to individual pension contributions. I think the support for social provision is overwhelming.

I think there is a consensus in this discussion around the ideas concerning secular stagnation, such as Thomas Piketty’s work about the growth of assets over the growth of income.

It is not a foregone conclusion. It is determined by a set of social decisions. Again, I would support what Hilary said earlier about the need for investment in newer technologies and the conservativeness of pension schemes in pushing things like action over climate change and innovation. That is where the growth will come from. It will not come from the stagnant economies and the stagnant technologies. Therefore, I think the issues around the active decision-making, rather than passive decision-making, of investors, are important in this process. For example, climate change is one of the key issues.

A final point I want to make is about quantitative easing.

If we talk about wealth transfer and intergenerational inequality, the impact of quantitative easing is what has driven that process. It is not people’s desire for pensions; it is not their desire for certainty in terms of pension provision and retirement; it is Government policy over the way in which the banking and the financial sector were rescued after 2007–2008. That is what has driven many of these changes.

There are some big questions here to be resolved; pension valuation assumption is one of the areas where the USS dispute has arisen. Inconsistency in application of assumptions in the USS case is one of the areas where major disagreements exist. The way in which assumptions have been built into the USS valuation has created the biggest dispute we have ever seen in higher education.

Part of the blame for that lies at the door of actuaries and the USS itself.

Mr R. K. Sloan, F.F.A.: I would not like this event to end without exposing the “elephant in the room”, namely the enormous amounts of final salary pension liabilities to which Allan Martin referred, being the root cause of the problem here.

I believe our profession has long needed to advocate much more pragmatic solutions to reducing clients’ risk exposure in pensions, towards which we had an ideal opportunity some 40 years ago – namely by opting-IN to SERPS (the new State Earnings Related Pension Scheme) and only topping-up with integrated Final Salary or Career Average private pension scheme benefits.

However, the vast majority of actuarial advisers recommended the much more risky approach of “contracting-OUT” of SERPS, thereby retaining for private schemes virtually full exposure to costly final salary benefits.

So, I think the problem is partly of The Profession’s own making by largely having gone for the easy option of contracting–OUT of SERPS, albeit no longer permitted. While such criticism cannot remove the problems that face us today, let us ensure that in future The Profession offers truly impartial advice on pension benefits and their means of provision.

Miss M. W. F. Wong, F.I.A.: The topic of your event today is, are we serving the public interest? As actuaries, we have traditionally been heavily involved in defined benefit schemes. Actuaries are not really involved in the design of future benefits for the future generation, so my question is, are we really serving the public interest by saying that actuaries are not needed to play a role in DC design?

The Chairman: I am going to insist on the panel giving us a very short answer: yes or no, are we serving the public interest?

Ms Salt: I would say a lot of the work that we have been doing is trying to find a way to introduce collective DC. I think that is really important. Postmen understand pension schemes as well as university lecturers now. I think that is somewhere where we can make a real difference.

Prof Cairns: As Director of the Actuarial Research Centre, I can point out that a colleague of mine and a researcher of hers at City University are working on a project that is sponsored by the profession through the ARC. It is looking at redesigning pensions, which is about risk-sharing and doing something different. It is not DC and it is not DB in its classical form.

The Chairman: Cathy, do you think we are serving the public interest as a profession or can we do better?

Ms C. Robertson F.F.A.: I think we are, yes. If I had been better prepared, I would have mentioned a group that we have looking at collective DC as well. But I think the short answer is yes.

The Chairman: Short answers are all we have time for now. Donald [Duval], are we serving the public interest?

Mr Duval: I think there is a danger in people trying to find alternatives to DC, bearing in mind that a sizeable proportion of the population always has had, and always will have, most of their benefits outside state benefits coming from DC. DB provision in this country peaked at just over 50% of the population. Remember, DC has always been the most important part of pension provision.

The Chairman: May I invite David Bowie to say a few words in closing?

Dr D. C. Bowie, F.F.A.: I had worried when I saw the title that we might degenerate into a long, technical debate about discount rates, which would have been a disappointing return to debates of the past. However, it was very pleasing that we engaged with some of the bigger issues instead.

Hilary Salt urged us to focus on how pension schemes could support the spread of wealth within society and across generations and suggested that open pension schemes were an important mechanism for so doing.

She also offered us what she regarded as evidence that the industry had “lost the plot” about the advice given. This evidence included the framework used by the regulator along with the impact on gilt yields, something echoed by Donald Duval in his contribution.

She was also critical of stochastic methodologies for assessing risk, largely because it over-engineered the analysis of some risks rather than looking at the bigger picture and picking up some unmodelled risks and consequences.

Donald Duval took more of an investment perspective. He painted a gloomy picture with falling gilt yields and falling expectations on equities, as well as the absence or the disappearance of many of the other premiums like illiquidity, on which pension funds have relied to date.

All of these observations led him to conclude that those parts of society who already had money had driven market conditions in such a way that wealth or opportunities to obtain wealth were unlikely to be distributed efficiently.

Andrew Cairns painted a similar picture. He contended that some of the actuarial methods have led to a loss of flexibility and that successive layers of regulation imposed on schemes were aimed at protecting the wealth that had accrued rather than wealth that might accrue in the future to existing generations, let alone to future generations.

He made the comment that perhaps the industry was overcompensating for a few “bad eggs”.

Andrew encouraged us as a profession to consider a wider risk appetite framework in which to try and frame our questions and our advice to pension schemes. That may be something that we can pick up and flow through to some of the Pensions Board projects.

The contributions from the floor re-emphasised the need for us as a profession to look beyond the narrow technical aspects of our role to the bigger picture in terms of the macroeconomics and wider political economy.

The point was made again about too much protection, about accrued wealth, and Mr Hamilton encouraged strongly to refer to gilts as future taxation as a way of reminding us what lay behind the asset class in terms of impact on society.

This perspective was picked up again by Alan [Martin] in his comments about the unfunded schemes effectively also being taxation on a future generation. He talked about the inconsistencies in the way in which funding protection exists in different pension funds ostensibly all within the public sector.

There were further questions on whether, when advising individuals, the profession can enable and encourage actuaries to take a bigger picture rather than being too narrowly focused.

We had responses from the panellists as to how pension funds should work for members, rather than the onus being on the member to engage and become educated about, which an analogy being drawn to how people “engage” with other utilities or tools, such as cars.

There were further comments based on the USS experience for schemes to provide secure pensions, but also an exhortation that pension funds might be used as funding for driving the productivity which is needed to leverage us out of the rather gloomy future which Donald [Duval] had originally set out.

The tone of the discussion was that the profession could helpfully contribute to inspiring something new and sparkling that would enhance our ability to generate wealth for future generations. Ronnie Sloan finished with suggesting that actuaries will need to focus again on getting involved in structuring the benefits in a better way. That echoed the point about actuaries getting back into being in the role of constructors in the industry and wider economy rather than purely “demolition experts”, in his words.