In a break with tradition and to celebrate the journal's 50th anniversary, this editorial will be longer than usual; the first section contains some practical announcements as well as obituaries and notable birthdays, while the second presents an analysis of contributor data for Britannia, and some suggestions for the future direction of the journal. The most notable practical change concerns the Editorial Board's decision to transition to an electronic submission system from 2020. Further details will be made available in the Notes for Contributors, and contributors are of course still encouraged to direct enquiries to the Editor first. The electronic submission system will enable the board to share editorial tasks more easily, especially as this year will also see the retirement of our invaluable Publications Secretary Lynn Pitts. The transition has been made much easier by the support and help of the outgoing editor Barry Burnham, to whom we are most grateful.

OBITUARIES AND CELEBRATIONS

Each year the editorial reflects on the deaths of scholars who made important contributions to Romano-British studies. Jennifer Price died on 17 May aged 79; she was an internationally renowned archaeologist and expert in Roman glass. Jenny was trained at the University of Cardiff, worked as Keeper of Archaeology in the Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum and taught in the Adult Education Department of Leeds University before moving to the University of Durham, where she earned a personal chair. Jenny's most notable publications include: the Council for British Archaeology Handbook of Romano-British Glass Vessels (with Sally Cottam) and Roman Vessel Glass from Excavations in Colchester 1971–85 (with Hilary Cool). To mark her retirement in 2005 the Association for the History of Glass organised a conference in Jenny's honour, the papers from which were subsequently published as Glass of the Roman World edited by Justine Bayley, Ian Freestone and Caroline Jackson.

This is also an opportunity to celebrate notable birthdays. The 10th of December 2019 sees the 80th birthday of Sir Barry Cunliffe, who taught at the Universities of Bristol, Southampton and Oxford. Barry's work has transformed understanding of the first millennia b.c. and a.d., and as noted in the Festschrift for his retirement,Footnote 1 his research transcends traditional chronological, spatial and thematic boundaries. To readers of Britannia his work on the key Roman sites at Bath, Fishbourne, Lympne, Richborough and Portchester will be most familiar, but Barry also conducted major excavation campaigns at the Iron Age sites of Danebury, Hengistbury Head, in the Channel Islands and beyond.

Richard Reece also celebrated his 80th birthday on 25 March 2019 (frontispiece). Richard was born in Cirencester, and while his first degree was in biochemistry, he had a long-standing interest in archaeological excavation, attending his first dig aged 16. His academic specialism is numismatics, and having completed a DPhil at Oxford, Richard went on to shape the study of Roman coinage through his innovative approach to analysis and interpretation as well as the publication of hundreds of site assemblages. ‘Reece periods’ and comparisons of coin loss profiles across sites have transformed interpretations, and his work on Roman coinage was recognised by the award of an honorary fellowship and its medal by the Royal Numismatic Society and the Derek Allen Prize by the British Academy. Perhaps his most profound impact derives from My Roman Britain, a short book privately published in 1987. Written in a highly personal and idiosyncratic style, the ideas expressed in this book have largely become mainstream, often promoted by the many archaeologists trained by Richard at the Institute of Archaeology (which eventually became part of UCL).Footnote 2 To his students and readers Richard promoted independent thinking and direct engagement with Roman material culture, and it is in recognition of his academic leadership that this volume of Britannia is dedicated to him.

BRITANNIA IN NUMBERS: 50 YEARS OF THE JOURNAL OF ROMANO-BRITISH AND KINDRED STUDIES

2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the creation of the journal Britannia, which was established as an off-shoot of the Journal of Roman Studies because of increasing interest in Roman Britain and the ever-growing number of excavations within this province.Footnote 3 For an event celebrating the 50-year milestone in London in 2017 (https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLO_zKwlRJ8jZIs_sx9wkHqcDI7V5rG5a1), I compiled some data to reflect on the journal's progress over the last half century, and to consider future directions. This builds on a similar exercise conducted by Sheppard Frere, Britannia’s first editor, writing in 2010 together with Roger Goodburn.Footnote 4

That piece highlighted fluctuations in volume length and cost as well as in the number and length of papers; it also discussed sources of funding and changing working practices, including the impact of the introduction of the computer. There are slightly wistful stories about editorial personnel re-drawing submitted sketches and engaging in original research. Frere and Goodburn also addressed editorial decisions about the balance of papers, notably the question of how Britannia should deal with site reports. The publication of excavation reports was one of the reasons for the creation of the journal, and for many decades remained very much at its core, but by 2005 the then editor, Simon Esmonde Cleary, stated that such papers would only be included if they were: (a) of national importance and (b) short.Footnote 5 The reasons given were cost as well as the length and complexity of modern excavation reports. In recent years, technological advances, notably the option of publishing detailed reports as online supplementary materials, are changing practices again as it becomes possible to publish sites of national and indeed international importance as part of a stimulating journal with additional detail available online.Footnote 6

‘Roman Britain in XX’, an annual update on Roman sites excavated within Britain is another stalwart of the journal where an increase in size has led to the decision to publish some material online. The decision as to what should be included in the print and the online supplementary section is made ‘with reference to the space available in the print journal, the significance of the findings, and the need to achieve a regional and thematic balance’.Footnote 7 The discussion of epigraphic material, recorded since 1921 by JRS, has been joined since 2004 by the most significant finds recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme. This includes an overview of the finds recorded each year as well as a catalogue of those of special interest.

WHO WRITES ON WHAT TOPICS?

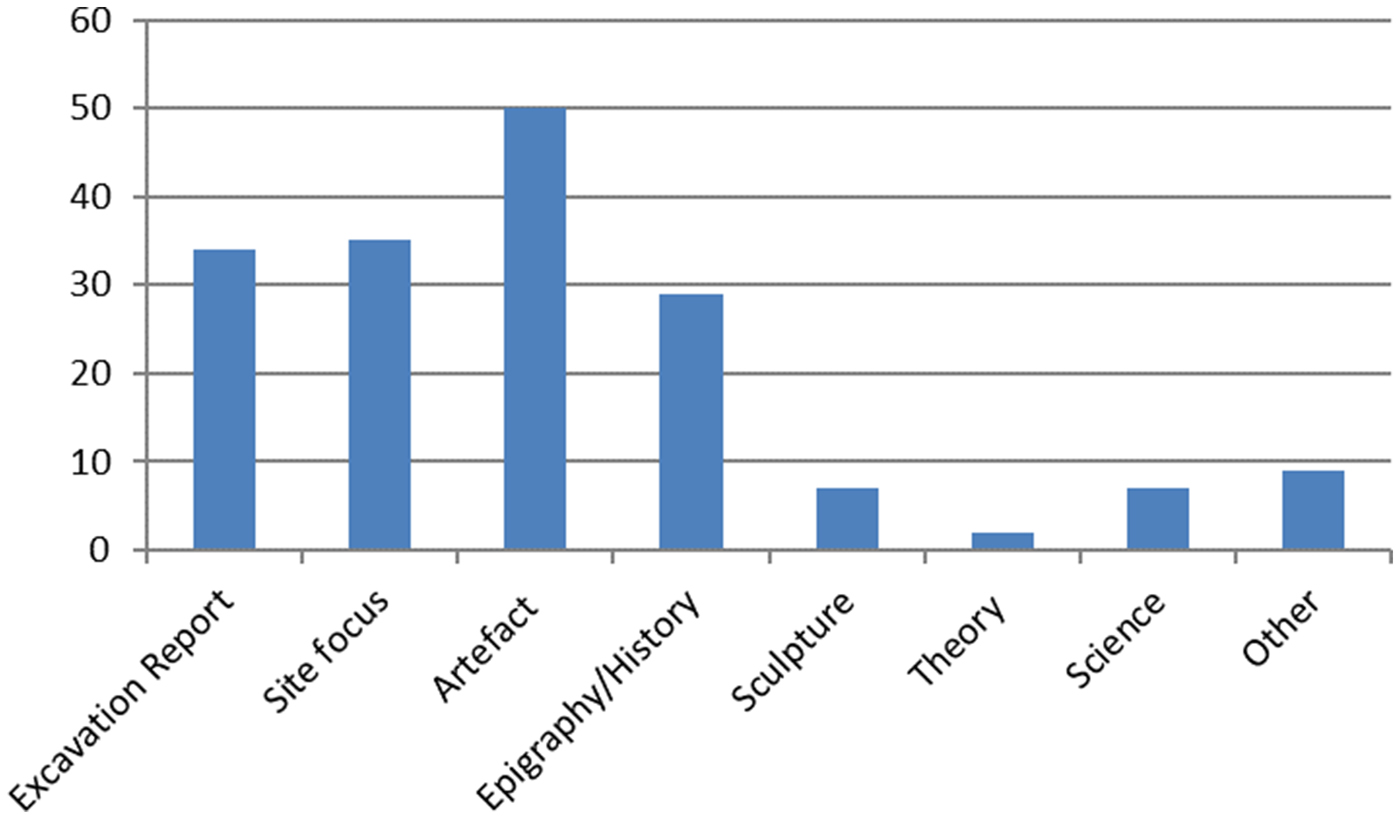

As Frere and Goodburn had considered the first 40 years of Britannia, the data analysis presented here will focus on the last ten years, and concentrate on issues (such as gender and professional affiliation, as well as subject matter) not addressed by them. I examined the 174 papers published between 1999 and 2016, but excluded shorter contributions and notes. In a first step, papers were grouped by subject matter (fig. 1). This is obviously a subjective assessment, and one may quibble over individual attributions, but some broad trends can nevertheless be identified.

FIG. 1. An attempt to group papers by subject matter (total number of papers: 174).

Papers on excavations or individual sites continue to feature heavily, as does research on inscriptions and other written materials. Articles discussing Romano-British material culture are another major element, with coins perhaps of particular importance. While many of these papers will contain a theoretical framework, it is very rare to see explicitly theoretical papers in Britannia. The two most notable examples are Gardner (Reference Gardner2013), ‘Thinking about imperialism: postcolonialism, globalisation and beyond?’ and Polm (Reference Polm2016), ‘Museum representations of Roman Britain and Roman London: a post-colonial perspective’. The success of the Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, first run in 1991 and accompanied by a publication of key papers each year since, has perhaps meant that contributors with an interest in archaeological theory have simply not considered Britannia, but it is also possible that the journal was perceived as too conservative or atheoretical.

Papers with an emphasis on archaeological science make up a small but growing proportion of Britannia contributions. This includes plant, pollen and zooarchaeological research, as well as geological assessments of building materials and isotope analysis of human remains. The concept of part-themed volumes was first raised in 2016Footnote 8 and implemented very successfully in 2017, with Volume 48 featuring four papers in a section on ‘New Approaches to the Bioarchaeology of Roman Britain’.

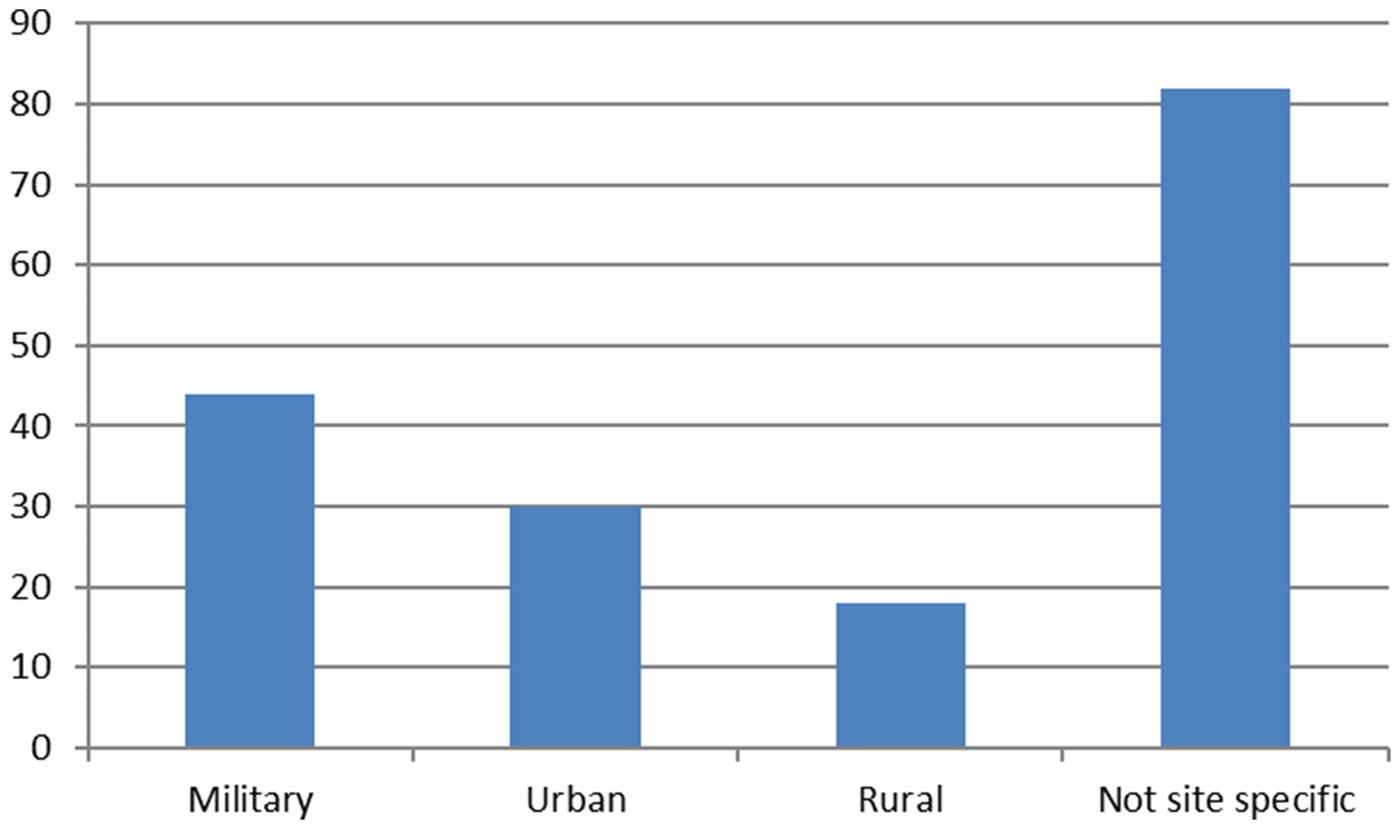

The majority of the 174 papers are not focused on a specific site, but amongst those that are, it is unsurprising that military and urban sites feature more frequently than rural sites (fig. 2). Even within the rural category, there has long been a bias towards villas rather than other types of sites.Footnote 9 These long-standing research traditions are only beginning to change, with recent work demonstrating the density and complexity of rural sites in the province.Footnote 10

FIG. 2. Types of sites discussed in 174 papers published between 1999 and 2016.

There are many more papers on England than on Scotland and Wales, again not that surprising given the existence of specialist regional publications on the latter regions and established research traditions.Footnote 11 Regional emphases can also be shaped by certain sites featuring repeatedly, e.g. London, Colchester, Silchester and Vindolanda.

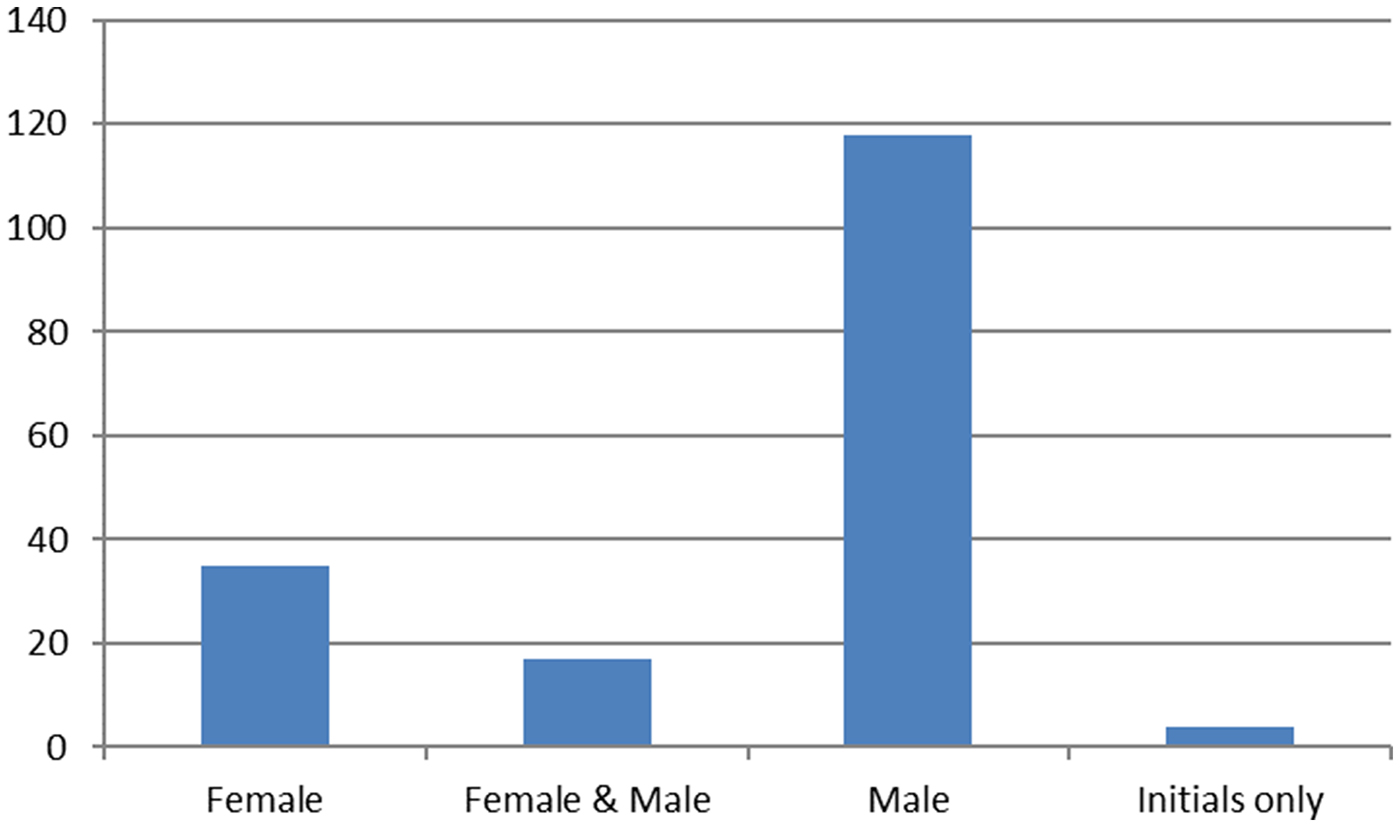

There has been much work on gender in the archaeological profession,Footnote 12 something not considered by Frere and Goodburn. It should be noted that many Britannia papers provide initials rather than full first names (and indeed some first names can be ambiguous) but it is nevertheless very clear that the journal, even in the last ten years, remains very heavily dominated by male contributors (fig. 3). It is not clear whether this disparity reflects unconscious bias in the review process or submission patterns, which in turn may reflect underlying equality and parity issues in the wider profession, although the latter perhaps seems more likely (see below).

FIG. 3. The number of male and female contributors (total: 174).

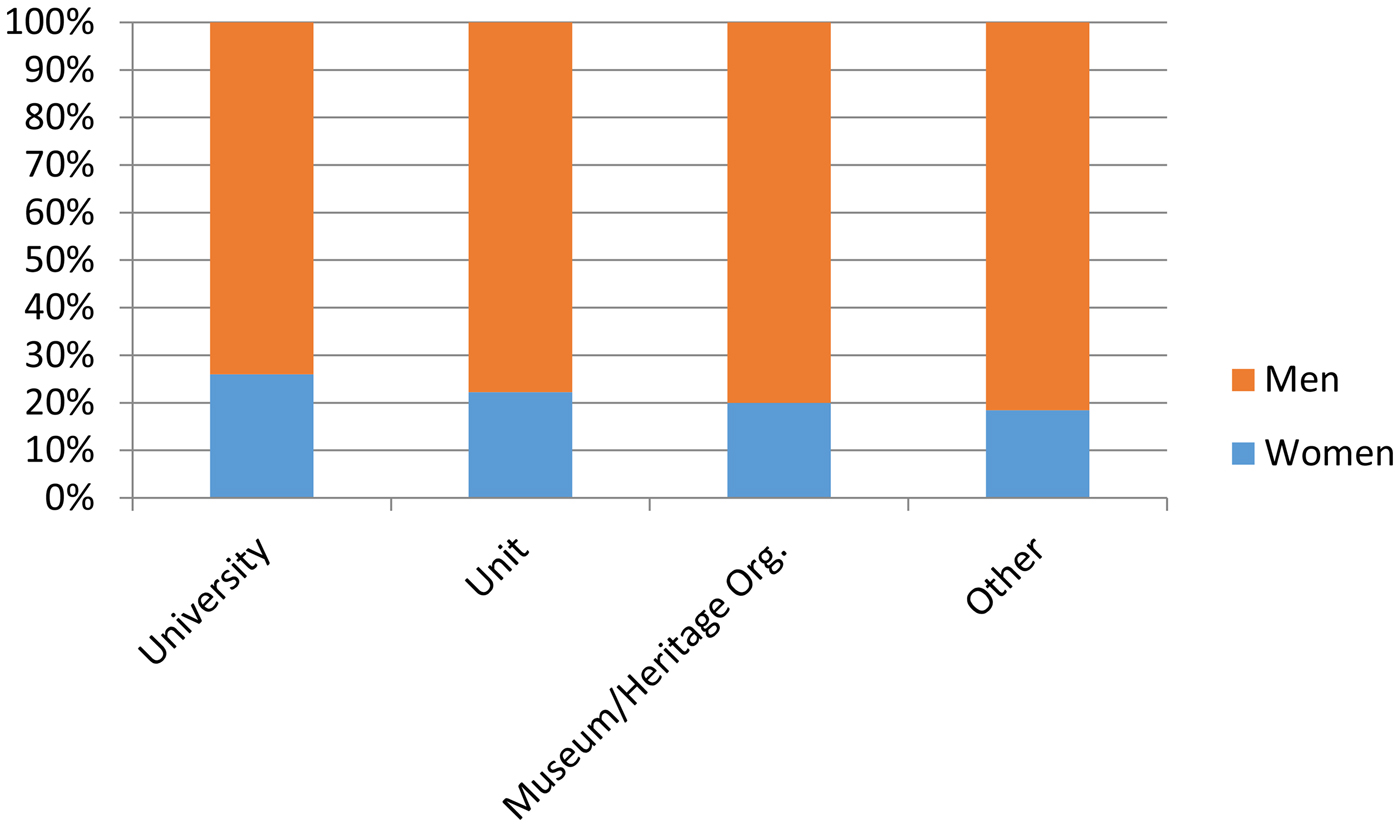

Breaking authors down by their professional association shows that relative gender proportions are quite consistent (fig. 4). In general, academics are major contributors to the journal, while organisations involved in development-led archaeology (archaeological units for short) and museum/heritage organisations feature less frequently. An even more marked bias towards academic contributors has been noted for TRAC (Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference) contributors.Footnote 13 This may be due to funding pressures, which are only likely to get worse. It is therefore important to consider ways of eliciting more contributions from those sectors (perhaps through promoting Roman Society grant funding specifically to units and museums, see below). Frere and GoodburnFootnote 14 noted that ‘much fundamental research work still remains, as it was in 1970, a matter for dedicated personal interest outside remunerated employment’ and this is borne out in the more recent contributions. This group includes interested amateurs, freelance archaeologists and retired professionals as well as authors who do not provide (and are presumed not to have) a professional affiliation.

FIG. 4. Proportion of single-author men and women by professional affiliation (total: 153).

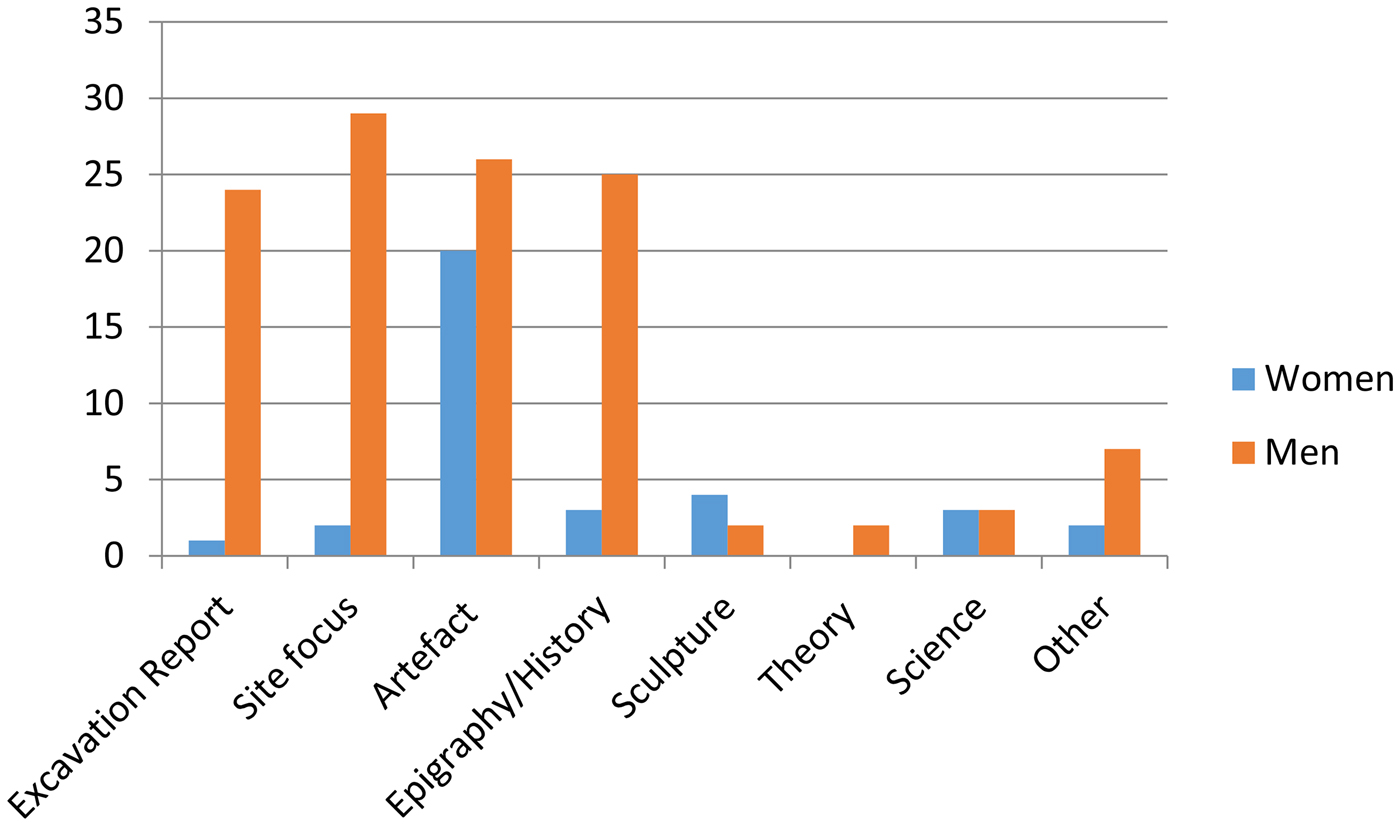

A much more striking picture emerges when we relate gender not to professional affiliation but to the content of the paper. Papers dealing with excavation and site reports as well as epigraphy are overwhelmingly written by men, while women more frequently write about artefacts and sculpture (fig. 5).

FIG. 5. Numbers of single-author male and female contributors by topic (total: 153).

Twelve years ago, Ellen SwiftFootnote 15 wrote about perceptions of finds research in the academic community. She combined a survey of papers published in Britannia between 1981 and 2001 with a questionnaire of finds specialists, focusing mainly on those working in universities. The proportions of men and women (61 to 39 per cent) closely mirrored those of archaeologists in British universities, but the questionnaires highlighted that finds work was seen as ‘low status’. She also noted that there was an absence of synthetic or analytical research on artefacts, with the mass of data available for the Roman period perhaps leading to a temptation to catalogue first.Footnote 16 I have not analysed the Britannia artefact papers in detail, but it is probably still true that within the broad ‘artefact’ category there are further trends, notably the association of numismatics research with men and that of small finds and glass with women.Footnote 17 Recent work on medieval archaeology highlights the ways in which gender continues to shape research agendas and contributor profiles in other sub-disciplines,Footnote 18 but on a positive note a survey of 24 TRAC conferences and nearly 800 TRAC papers identified a good gender balance as well as increasing engagement of non-UK based scholars.Footnote 19

KINDRED STUDIES AND AN INTERNATIONAL OUTLOOK

Britannia is styled as a ‘Journal of Romano-British and kindred studies’, a slightly awkward name designed to incorporate papers that deal with the late Iron Age and the immediate post-Roman period in Britain, as well as the wider Roman Empire or perhaps more accurately the western provinces.Footnote 20

Earlier generations of scholars had very close continental networks, something that is still evident for military specialists but perhaps less so for other sub-disciplines. Thus in his editorial for the first volume of Britannia Frere provided quite a lengthy discussion of German scholarly publications of relevance to the journal.Footnote 21 In 2010, Frere and Goodburn took a rather positive view about the proportion of kindred studies papers, but their own table shows that numbers of papers dealing with continental comparanda have decreased quite markedly over time while those on Iron Age and late/post-Roman topics continue to make up a small but steady proportion. With regards to the decline of papers comparing Roman Britain to the nearby Continent, or of papers discussing the north-western provinces generally, Frere and Goodburn noted the impact of the Journal of Roman Archaeology, which began publication in 1988.Footnote 22 The success of JRA may indeed have contributed to a gradual and increasing conviction in the mind of both readership and contributors that Britannia deals with purely British matters. On the other hand, a cursory survey of the articles (not notes) published by JRA between 1999 and 2016 shows that papers about Roman Britain are actually relatively rare, with those about the north-western provinces only marginally better represented (of an average 13 papers in the 18 volumes examined, only one volume (2005) has two papers focused on Britain, and only seven volumes contain work on Roman Britain).

Returning to Britannia, my survey only identified 17 (10 per cent) of papers that could confidently be classed as belonging to the category of kindred studies (Table 1). The four Iron Age papers include three on coins, with numismatics generally featuring in Britannia quite regularly, and one on iron deposition. The six very late/immediately post-Roman papers discuss historical figures, some continental material and the re-use of Roman building material in later churches. The seven papers addressing material from the north-western provinces with relevance to Britain are extremely diverse, covering topics such as Gallo-Roman cats, Egyptian amphorae and magic figurines. Another way of considering the journal's international outlook is by counting non-UK based contributors — whether they write about British sites or collections,Footnote 23 nearby continental sites that may serve as models for understanding BritanniaFootnote 24 or about object types that occur both in Britain and on the Continent.Footnote 25

TABLE 1 KINDRED-STUDIES IN BRITANNIA

The tension between a focus on Britain and a more ‘international’ outlook is of course not only evident in the Roman period. In his analysis of the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society ChapmanFootnote 26 warned against a ‘little England’ mentality, while WilsonFootnote 27 reasserted the value of a British focus for the journal Medieval Archaeology when celebrating that society's 50th anniversary in 2007.

CONCLUSION

While we can be justifiably proud of the excellent work on Roman Britain published in Britannia over the last 50 years, the Retrospect and Prospect conference was a useful opportunity to take stock, and to debate the appropriate balance between being a journal of record, a journal for debate or indeed a journal for both. The Editorial Board is very keen to encourage dialogue between those interested in archaeological theory and those keen to present the rich empirical data the Roman world has to offer. Building on the 2017 volume that focused on bioarchaeology, we plan further part-themed volumes, on contrasting approaches to urban and rural sites in 2020 and Roman frontiers in 2022. Suggestions for other themed volumes are most welcome! Finally, we would also like to encourage more papers that put Britain within its continental context, especially now given the potential impact of Brexit.Footnote 28

As a result of the data highlighted by my survey, the Editorial Board would also like to encourage submissions from groups that have perhaps not traditionally published in Britannia, notably women, early career scholars and those working in units and museums. We are very conscious of the under-representation of not just women in archaeology but also the discipline's record on socio-economic and ethnic diversity.Footnote 29 One way to improve matters is through making contributors aware of grants that could cover the cost of post-excavation and publication costs, such as those offered jointly by the Roman Research Trust and the Roman Society (http://www.romansociety.org/grants-prizes/audrey-barrie-brown-memorial-fund-donald-atkinson-fund.html).

For some time, Britannia’s Editorial Board has made an effort to recruit members from units, museums and academia, to maintain a fair gender and age balance and to cover a range of specialisms. Traditionally, new Editorial Board members have been approached on the basis of suggestions made by existing members, but from 2020 we invite applications from all interested parties to join the Editorial Board, which will be reviewed once a year at the March editorial meeting. We hope that this will not only reduce unconscious bias but also further broaden the diversity of the Editorial Board, from which the Review Editor and Editor are chosen every four to five years. Perhaps indicating that the existing system was already much more outward looking than may be assumed, I am very honoured to serve as the first female editor of Britannia, and as the first editor not born and raised within Britain.

There is clearly scope for more detailed historiographic analysis of Britannia, and indeed of the Roman Society as a whole. Thus for the Prehistoric Society Chapman provides some interesting data on grants awarded and compares membership numbers in comparison to other societies.Footnote 30 Even more detailed analysis of publication trends in that journal has been conducted by Cooper, who analysed the types of prehistoric archaeology investigated (e.g. fieldwork report, artefact study, work of synthesis), the geographical distribution of fieldwork and the professional affiliations of contributors to the Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society from 1980 to 2005.Footnote 31 Her work is nuanced and detailed, and crucially includes a qualitative assessment of shifting interpretative trends. Similar, qualitative work on interpretative trends has been carried out for the Roman period by Pitts, who explored the changing use of the concept of identity within the discipline by analysing conference proceedings and other publications.Footnote 32

Britannia will continue to maintain a close relationship with our readers, and of course aim to increase circulation to attract new ones. The journal's publishers Cambridge University Press now provide the Editorial Board with detailed data on the most downloaded papers, distinguishing between abstract views and full text views. The most downloaded paper is Gardner on postcolonial theory,Footnote 33 followed by Hingley on the deposition of iron objects.Footnote 34 In both cases, the figures may reflect an audience of younger, technologically-adept researchers interested in theoretical archaeology. The third most popular paper on the other hand is Bowman et al. on the Vindolanda writing-tablets.Footnote 35 CUP also supplies information on the institutions with the most downloads, highlighting the international readership of the journal in the USA and Australia but also Germany.Footnote 36

In a world of easily accessible news, Britannia will also have to work harder to engage with new audiences through news and social media. Since 2012, Britannia has had a slowly increasing presence on blogs, Facebook and Twitter. Again, CUP provides detailed altmetric data; this complements traditional metrics such as citation indices and calculates a paper's impact across online media. For example, a gold finger-ring depicting a cupid reported by Worrell and Pearce triggered a great deal of interest in the media, as did an article about a centurion from Britain who died in Bostra in Arabia.Footnote 37 More can be done. One way may be to increase the visibility of research on Roman Britain, following the example set by the Women's Classical Committee, which has recently systematically updated or created Wikipedia pages for female archaeologists and classicists, which in 2017 had made up only 10 per cent of such entries.Footnote 38 The Roman period holds a wealth of material of great relevance to the modern world, but as a Society there is clearly much to learn about appropriate social media communication. The most striking recent example is the torrent of abuse faced by Professor Mary Beard, when she asserted the case for ethnic diversity in Roman Britain.Footnote 39

We clearly need to learn more about our readers, and steps are underway to conduct a survey of the readership. Many readers, especially those working in academic institutions, now access the journal only electronically. However, in the inevitable, gradual shift to online publication we must take care not to ignore those readers who prefer (or can only access) hardcopy versions of Britannia. Another issue that will feature in editorial meetings for both Britannia and JRS in the coming years is whether and how to balance the needs of the Society with the increasing trend towards Open Access publishing.

Ultimately, what is published in Britannia is selected from papers offered to the Editor, and it is hoped that the enthusiasm for new directions expressed at the 50th anniversary conference in London is reflected in submissions over the next few years. Britannia has done an excellent job in shaping and reflecting the state of Roman archaeology in the provinces by publishing high quality work, and the Editorial Board hopes to continue this tradition. Our interest in debate and dialogue, and in widening the range of contributors even further, should help Britannia to achieve this goal.