Background

The healthcare waiting-room setting presents an opportunity to offer a variety of interventions to patients. The average amount of time people spend in a physician's waiting room varies between 19 and 50 min.Reference Barlow1,2 Sherwin et al suggest that waiting rooms can be used for a variety of interventions, for example to complete validated questionnaires, question prompt sheets or brief training, and provide patient education material and decision aids.Reference Sherwin, McKeown, Evans and Bhattacharyya3

Only limited literature is available on the use and evaluation of specific interventions developed for waiting rooms. Few studies have assessed the impact of interventions provided in the waiting room. These studies are mostly limited to health education delivered in a variety of formats, ranging from pamphlets to audiovisual aids and in a variety of healthcare settings.Reference Assathiany, Kemeny, Sznajder, Hummel, Van Egroo and Chevallier4–Reference Wicke, Lorge, Coppin and Jones10

Evidence suggests that single-session interventions can be effective in managing a variety of mental and emotional health problems.Reference Amir, Bomyea and Beard11–Reference Miloff, Lindner, Hamilton, Reuterskiöld, Andersson and Carlbring17 There is also evidence that a brief video intervention might help with mental health problems.Reference Hoffman, Pitcho-Prelorentzos, Ring and Ben-Ezra18 Therefore, we believe that waiting-room interventions for psychiatric settings can go beyond simple educational material and psychiatric interventions can be offered through digital media, including audiovisual material.

We performed a literature search to identify studies of waiting-room interventions in mental health. We did not find a published report on the development or evaluation of a waiting-room intervention explicitly developed for psychiatric patients. We developed a waiting room video intervention, RESOLVE (Relaxation Exercise, SOLving problem and cognitiVe Errors), for the psychiatric waiting room. This paper reports the results of a proof-of-concept study that evaluated the intervention in a crisis clinic.

Development of RESOLVE

RESOLVE was developed following clinical observations by us, informal discussions with clinical colleagues and experts in the field. Clinical observations suggest that employing relaxation strategies, analysing the problem and better understanding our thought processes are useful first steps towards feeling better. We decided to focus on problem-solving therapy (PST) as this approach can be taught using electronic media. A video was produced based on this problem-solving approach. PST is effective for a variety of mental health problems.Reference Naeem, Munshi, Xiang, Yang, Shokraneh and Syed19,Reference Bell and D'Zurilla20 People in distress often have difficulties thinking clearly about their situation and what might help to improve it and a problem-solving approach may be useful in helping people presenting to crisis or emergency services.Reference Xia and Li21 One reason for people to seek help from psychiatric crisis services is that their ability to cope and solve problems on their own has been insufficient.Reference Bilsker and Forster22 Mindfulness-based breathing exercises have also been found to be useful in helping those with mental health problems.Reference Khoury, Lecomte, Gaudiano and Paquin23 There is sufficient evidence to suggest a role for breathing exercises in dealing with stress, anxiety and negative affect.Reference Ma, Yue, Gong, Zhang, Duan and Shi24 According to cognitive theory, our dysfunctional thoughts lead to extreme emotions.Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery25 Fu et al (2013)Reference Fu, Du, Au and Lau16 reported that a single session of cognitive bias modification training could reduce negative interpretations in adolescents with anxiety disorders. Hence, a brief introduction to common cognitive errors was considered of potential use.

We developed a video containing information on breathing exercises, information about cognitive errors and problem-solving skills. The video can be delivered using electronic media (for example on a television screen) in waiting rooms. The video starts with an explanation of breathing exercises, with an explanation of the fight and flight centre and how the centre is activated during stress, and explaining the breathing method in detail. The major part of the video revolves around a fictional character who uses steps in solving a problem to sort out a financial problem. These steps include defining the problems, making a list of problems, choosing the right solution and acting on it in small steps. Finally, the narrator explains common cognitive errors, each with an image and an example. This intervention is only 8 min 38 s long and can be shown while patients are in a waiting room in a psychiatric crisis clinic. It can be accessed at: (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=53BA7l3v6ZA&t=53s).

Treatment as usual

All study participants received treatment as usual (TAU), which mainly consisted of weekly or biweekly contacts with a caseworker who usually worked with the clients to monitor mental state, ensure medication adherence, help with practical issues such as housing, etc. Social workers and psychiatrist also supported clients.

Method

Objectives

The objectives of the study were to test the trial procedure and obtain outcome data to inform future definitive trials.

Study design and setting

This proof-of-concept study used a randomised, single-blind, controlled trial design (trial registration at Clinicaltrials.gov NCT02536924, REB Number: PSIY-477-15). It was conducted from January 2016 to January 2017. The local institutional review board at Queens University, Kingston, Canada, approved the trial protocol. After a full description of the study, all participants provided written informed consent before entering the study. The intervention group received RESOLVE and TAU, and the control group received TAU.

Inclusions and exclusion criteria

Individuals were included if they were ≥18 years, were attending crisis service for the first time and had a diagnosis of a mood or anxiety disorder according to the DSM-IV.26 Individuals with substance dependence, active psychosis, organic brain syndrome or intellectual disability, as well as those with high levels of disturbed behaviour, were excluded.

Participants

Participants were recruited for the study during their visit to the crisis team walk-in services in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Following their appointment with a crisis worker, participants were asked by their worker if they would like to participate in a research project. A member of the research team then contacted those considered suitable and invited them to participate in the study. Consenting participants were randomly allocated to intervention or control in a 1:1 ratio.

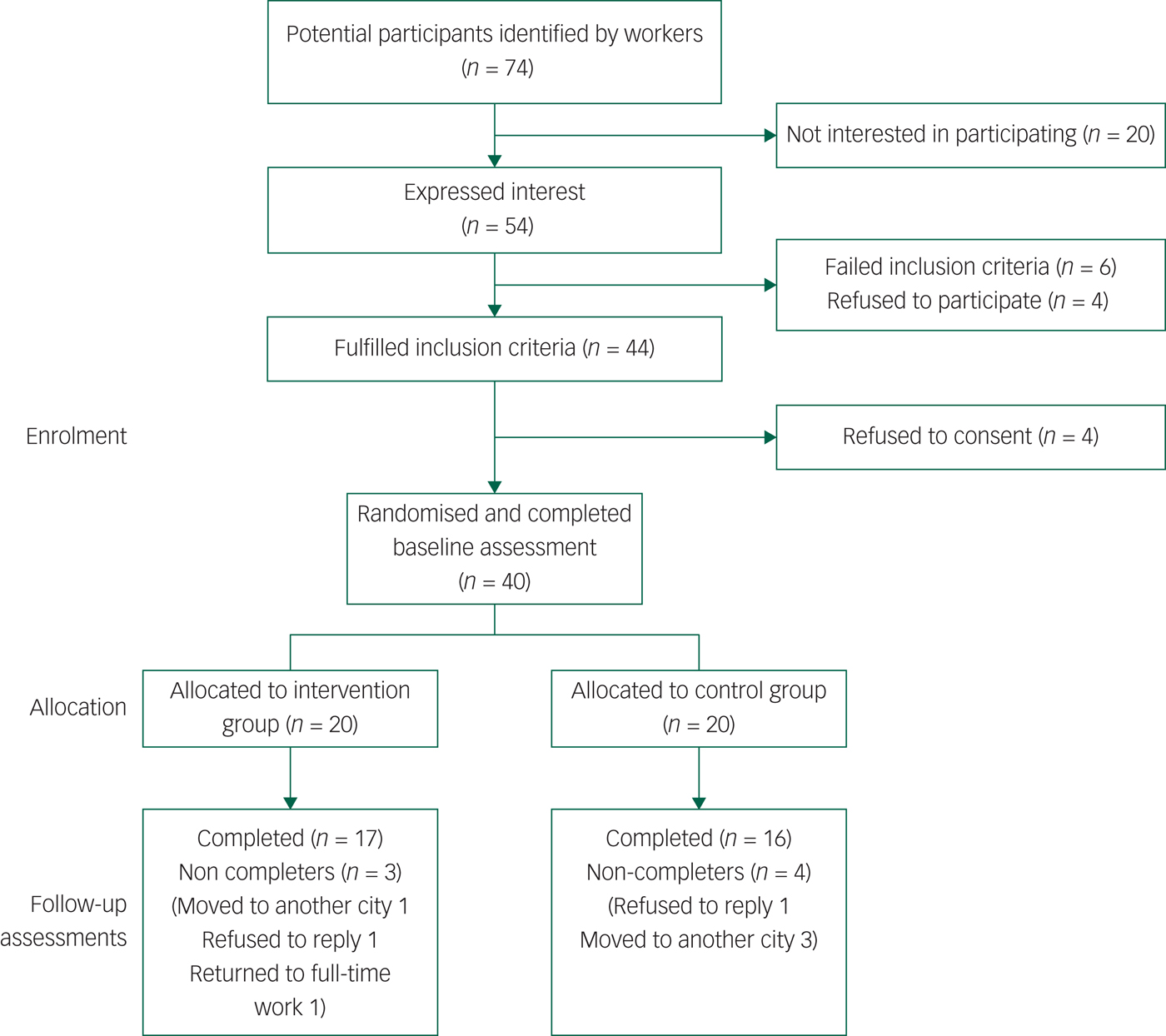

We enrolled 40 individuals, assigned randomly to the intervention group (n = 20) or the control group (n = 20). Three individuals from the intervention and four from the control group were not contactable for final assessment (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Consort flow diagram of the trial.

Procedures

Clinical staff identified 74 individuals who could potentially meet the inclusion criteria for the study. Research staff contacted this group, and 54 expressed interest in participating in the study. Out of 44 individuals considered suitable after the initial assessment, 40 individuals consented to and participated in the study (Fig. 1). Participants in the intervention arm were invited to watch the video in one of the assessment rooms adjacent to the waiting room. They were then given a copy of the video and handouts on problem-solving, relaxation and cognitive errors. Those in the control arm were offered only routine care.

Individuals who met inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to either the intervention (n = 20) or control (n = 20) only. Randomisation was performed using computer-generated numbers from a website (www.randomization.com). Block randomisation with randomly permuted block size was used to ensure similar numbers of participants were allocated to each arm of the trial. Individuals were assigned to either intervention or the control arm by the research team members who were independent of the assessment team.

Outcome measures

Outcome assessments were carried out by raters who were independent of those providing the intervention and masked to the intervention allocation and adherence. At the 6-week follow-up, participants had the option of completing the assessments in person or over the phone.

The following assessments were performed at baseline and 6 weeks; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery25 the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluations (CORE) outcome measure,Reference Üstün, Chatterji, Kostanjsek, Rehm, Kennedy and Epping-Jordan28 the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DAS) 2.0Reference Zigmond and Snaith27 and documentation of the number of contacts with the mental health services during the prior 4 weeks. The CORE was used to capture a broader range of symptoms and to see whether the change in psychopathology went above and beyond the anxiety and depressive symptoms. Finally, we decided to measure the change in disability to find out whether symptomatic change, if any, accompanied improvement in functioning or not. We also wanted to see whether this intervention will reduce the frequency of contacts with the service and therefore looked into this variable independently.

The HADSReference Zigmond and Snaith27 is a 14 item, self-assessment scale designed to measure anxiety and depression. It has high internal consistency, face validity and concurrent validity. Even numbered questions relate to depression and odd numbered questions relate to anxiety. Each question has four possible responses. Responses are scored on a scale from 0 to 3. The maximum score is 21 for depression and 21 for anxiety. A score of 11 or higher indicates the probable presence of depression, whereas a score of 8 to 10 is suggestive of the presence of the respective state. In its current form the HADS is now divided into three ranges: normal (0–7), borderline abnormal (8–10), ‘cases’ (11–21).

The brief WHO-DAS 2.0Reference Üstün, Chatterji, Kostanjsek, Rehm, Kennedy and Epping-Jordan28 is a 12-item self-report questionnaire that assesses disability and functioning in the prior month. The WHO-DAS 2.0 was developed to assess six different adult life tasks: (a) understanding and communication; (b) self-care; (c) mobility (getting around); (d) interpersonal relationships (getting along with others); (e) work and household roles (life activities); and (f) community and civic roles (participation).

The CORE outcome measureReference Evans, Mellor-Clark, Margison, Barkham, Audin and Connell29 is a self-report questionnaire that asks 34 questions about how a person has been feeling over the past week. It uses a five-point scale ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘most or all of the time’. The 34 items of the measure cover four dimensions: subjective well-being, problems/symptoms, life functioning, risk/harm.

The sample size

This is a proof-of-concept study using an randomised control trial design. Therefore, no power calculation was conducted. The results of this proof-of-concept study will be used to calculate sample sizes for future larger randomised controlled trials. It has been suggested that a sample size of 12 in each arm should suffice for pilot studies.Reference Julious30 Allowing for up to 40% drop-out, we, therefore, recruited 40 participants for the study, including 20 participants per arm.

Statistical analyses

The analyses were carried out using SPSS v24. A descriptive analysis of the randomisation groups relative to its baseline characteristics was conducted where means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Because of the small sample sizes, group comparison at baseline was conducted using Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables. Our main analysis compared the outcomes at 6 weeks using the ANCOVA approach where the outcome at week 6 is specified as the dependent variable, and the treatment group along with baseline value of the outcome are specified as predictors. As this is a proof-of-concept study, we have not adjusted P-values for multiple comparisons and used only data for completers in our main analysis. A sensitivity analysis that imputed outcomes using last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) obtained almost identical results. In our case, we consider the LOCF approach conservative as most participants were observed to improve over time and LOCF necessarily forces the outcome to be stable over time. For practical interpretation, we also report raw Cohen's d effect sizes.

Results

Participants had a mean age of 30.3 years (range 20–52), with an almost equal gender ratio with 53% women (n = 21). They had a mean of 2.45 (range 0–10) past admissions in a psychiatric facility. Most clients were ethnically White (n = 32, 80%), were single (n = 21, 52.5%) and had college education (n = 26, 65%). In terms of diagnoses, 30.0% (n = 12) had depression, 10.0% (n = 4) had generalised anxiety disorder, 12.5% (n = 5) had post-traumatic stress disorder, 25% (n = 10) had mixed anxiety and depression, 2.5% (n = 1) had a personality disorder, 7.5% (n = 3) had an anxiety disorder, 7.5% (n = 3) had an adjustment disorder and 5% (n = 2) had more than one diagnosis.

At baseline 40.0% (n = 16) were using antidepressants. Percentages for other baseline medications were 2.5% (n = 1) anxiolytics, 2.5% (n = 1) antipsychotics, 35.0% (n = 14) mood stabilisers and 20.0% (n = 8) were on multiple medication. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the individuals in the intervention and control groups are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences in any baseline values between the two groups.

Table 1 Differences in demographic variables and psychopathology between the intervention and the control groups at baseline

TAU, treatment as usual; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; CORE, Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluations outcome measure; WHO-DAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0.

a. P-values were calculated using non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables (age and clinical matrices) and Fisher's exact test for the rest of variables that were categorical.

b. Family history of any psychiatric diagnosis.

Table 2 shows the results of the ANCOVA. Both the differences at the end of the intervention period and differences controlled for baseline are described. The participants in the treatment group showed significantly greater improvements on total HADS score (P < 0.001), anxiety subscale of HADS (P < 0.001), depression subscale of HADS (P ≤ 0.001), CORE (P ≤ 0.001) and disability (P = 0.036) from baseline compared with the participants in the control group at the end of the study period. Participants in the intervention group also made fewer contacts with the mental health professionals during the past 4 weeks at the end of the study period (intervention, median 1.0 (interquartile range (IQR) = 3.0), control mean 4.0 (IQR = 2.0), P<0.001) as per the electronic health record system.

Table 2 Differences between the treatment and control groups, both uncontrolled and controlled for baseline differences

TAU, treatment as usual; numDF, numerators for degrees of freedom; denDF, denominators for degrees of freedom; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; CORE, Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluations outcome measure; WHO-DAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0.

a. Cohen's d was calculated by dividing the adjusted difference at the end of the trial by the pooled SD at baseline.

b. P-values calculated using ANCOVA, controlling for baseline value of the outcome.

We performed a sensitivity analysis for each outcome with missing values at the end of the trial imputed using the LOCF method. Results are shown in Table 3. None of the conclusions mentioned previous changed.

Table 3 Sensitivity analysisa

TAU, treatment as usual; numDF, numerators for degrees of freedom; denDF, denominators for degrees of freedom; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; CORE, Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluations outcome measure; WHO-DAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0.

a. Last-observation carried-forward was used to impute missing values for the seven patients who dropped out. Differences between the treatment and control groups, both uncontrolled and controlled for baseline differences. Analyses were carried out using an ANCOVA.

b. Cohen's d was calculated by dividing the adjusted difference at end of trial by the pooled standard deviation at baseline.

c. P-values calculated using ANCOVA, controlling for baseline value of the outcome.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the development and pilot testing of an intervention using a waiting-room setting and based on an evidence-based therapy for common mental disorders. Those receiving the intervention showed improvement in depression, anxiety, general psychopathology and disability. These participants were also less likely to seek professional help compared with those in the control group. This has potential implications for healthcare costs. These initial results are encouraging and provide new opportunities for providing brief psychosocial interventions to people in a waiting room. Although we tested the intervention in a crisis clinic setting, it has the potential to be used in general psychiatric waiting rooms as well as in general medical waiting rooms or primary care settings.

There is significant prior evidence for the effectiveness of PST, mindfulness breathing and teaching cognitive errors for common mental disorders. This report confirms prior studies that PST can be effective for a variety of conditions, including psychiatric and physical health problems.

This work is in line with past reports of the success of single-session psychological interventions. One session of cognitive behavioural therapy has been used to treat traumaReference Başoğlu, Şalcioğlu and Livanou12,Reference Bisson13 anxiety for depression,Reference Kunik, Braun, Stanley, Wristers, Molinari and Stoebner31 for medication adherence for depression,Reference Safren, O'Cleirigh, Tan, Raminani, Reilly and Otto32 for anxiety disorders,Reference Amir, Bomyea and Beard11,Reference De Jongh, Muris, Horst, Van Zuuren, Schoenmakers and Makkes33,Reference Öst34 for pain catastrophizingReference Darnall, Sturgeon, Kao, Hah and Mackey35 and for addiction problems.Reference Copeland, Swift, Roffman and Stephens36 Similarly, a single session of motivational interviewing has been shown to be effective for the treatment of addiction as well as in treatment adherence.Reference Brand, Bray, MacNeill, Catley and Williams14,Reference Diskin and Hodgins15,Reference Copeland, Swift, Roffman and Stephens36 Single-session interventions have also been tested and found to be effective using virtual reality programs for anxiety disorders.Reference Miloff, Lindner, Hamilton, Reuterskiöld, Andersson and Carlbring17,Reference Berman, Forsberg, Durbeej, Källmén and Hermansson37

We aimed to develop a similar intervention using a video and the time spent in the waiting area. We found the intervention to be useful for the management of psychological distress. This might prove to be a cost-efficient way of delivering an intervention that is likely to be useful for a variety of conditions including psychiatric and physical health conditions. The participants for this trial were selected from a crisis team but the intervention could also be used in other settings such as waiting rooms for community mental health teams or primary care.

We believe that the waiting room could offer a suitable venue for providing psychosocial interventions. Patients spend a varying amount of time in waiting areas before healthcare professionals see them. This is the time when patients may be more receptive, and an intervention can not only help overcome anxiety in the waiting room but also can have a long-term beneficial effect. This may explain the significant effect of the intervention on depressive and anxiety symptoms

Limitations

Limitations include the small sample size and a short follow-up period. As such, more data is warranted to confirm these results. Participants in the intervention arm were invited individually to a small room adjacent to the waiting room to watch the video. In real life, not all those sitting in the waiting room might be receptive to the intervention. It is of note that the effect sizes were larger for psychopathology than disability. We also recognise that the large effect sizes might be because of the small sample size. Although this is a small study, future enhancements in the intervention could include behavioural activation to improve functional outcomes. Future studies need to include those with severe mental illness, and issues with substance misuse – the intervention in its current form was only tested with people with more common mental disorders. Similarly, the intervention was tested in a crisis clinic, although we believe it can be easily used in other medical and psychiatric settings.

Implications

Patients spend a significant amount of their time in psychiatric waiting rooms. This study confirms past reports of the efficacy of a single-session psychosocial intervention. However, the intervention in this group was delivered through a video instead of a therapist. In this proof-of-concept study, we found that evidence-based interventions could be delivered through electronic media to a group of patients in the waiting room of a crisis team. We found that the intervention was acceptable and significantly improved anxiety and depressive symptoms. Further research is required to validate these findings with adequately powered trials with better methodology.

Funding

The study was funded by a small internal grant by the Department of Psychiatry, Queens University, Kingston, Ontario.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all the participants. We also acknowledge Chris Trimmer, Richard Tyo, Hanna Taalman for collecting data. We are grateful to Tania Leverty and other members of the team for facilitating the study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.