Introduction

Sleep is a biological necessity, essential for infant, child and adolescent growth; metabolism and immune system regulation; and normal memory and affect.Reference Mindell, Owens and Carskadon1,Reference Penn and Shatz2 This narrative review aims to serve as a clinician's guide, and will describe the following in children and young people: normal sleep, sleep disorders, the effect of affective disorders on sleep, the effect of disturbed sleep on mood and the role of targeted sleep therapy, particularly with respect to mood. Awareness of this complex relationship among healthcare professionals working with children and young people could lead to better care and improved long-term outcomes. This review does not discuss the relationship between sleep and affective disorders in children and young people with a neurodevelopmental disorder, such as hyperkinetic disorders, autism spectrum disorder and/or intellectual disabilities.

Normal sleep

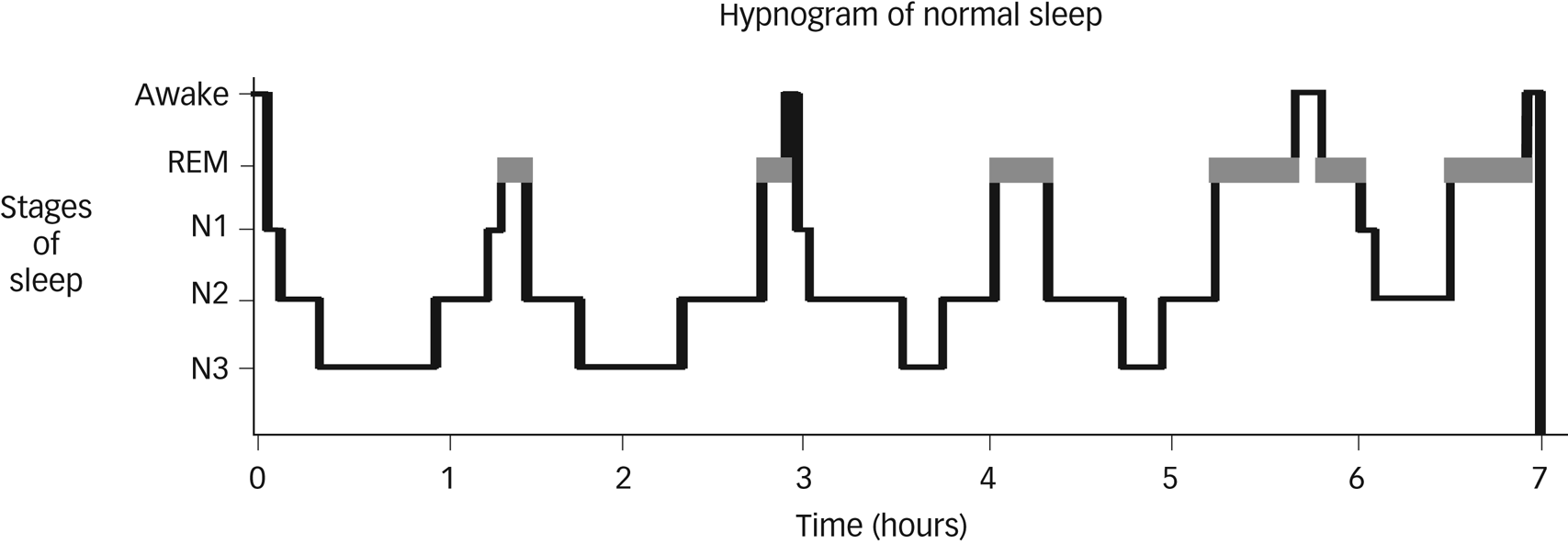

Sleep is composed of two phases: rapid eye movement (REM) and non-rapid eye movement (NREM).Reference Gelder3,Reference Carley and Farabi4 NREM sleep is further divided into stages N1, N2 and N3, with stage N3 known as slow-wave sleep (SWS). REM sleep is associated with inhibition of peripheral muscle tone, along with active cortical function and increased blood pressure, heart and respiration rates.Reference Mindell, Owens and Carskadon1 The switches that result in the cycling between REM and NREM are facilitated by monoaminergic and cholinergic neurons within the brain-stem (see Figs 1–3).Reference Hobson, McCarley and Wyzinski5 Sleep is essential in the development of neurosensory, memory and motor systems in the foetus and neonate, and in the maintenance of brain plasticity over the lifetime.Reference Penn and Shatz2 The overall regulation of sleep depends on two major processes: the sleep–wake homeostatic process and the circadian timing system. The homeostatic process ensures that the longer a person stays awake, the more pressure there is to fall asleep.Reference Czeisler, Duffy, Shanahan, Brown, Mitchell and Rimmer6

Fig. 1 Hypnogram showing normal sleep in an adult. Non-rapid eye movement sleep is split into stages N1–N3. Courtesy of Dr Kirstie N. Anderson. REM, rapid eye movement.

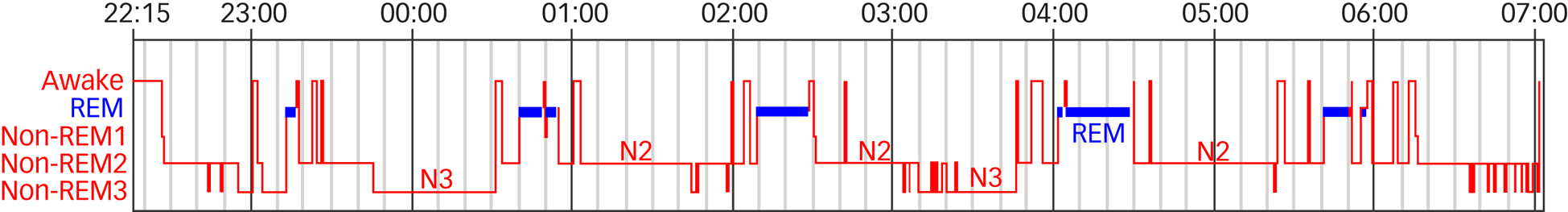

Fig. 2 Hypnogram of a 9-year-old boy with a short sleep onset latency and shorter sleep cycle duration. Non-rapid eye movement sleep is split into stages N1–N3. Courtesy of Dr Elizabeth A. Hill, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh.

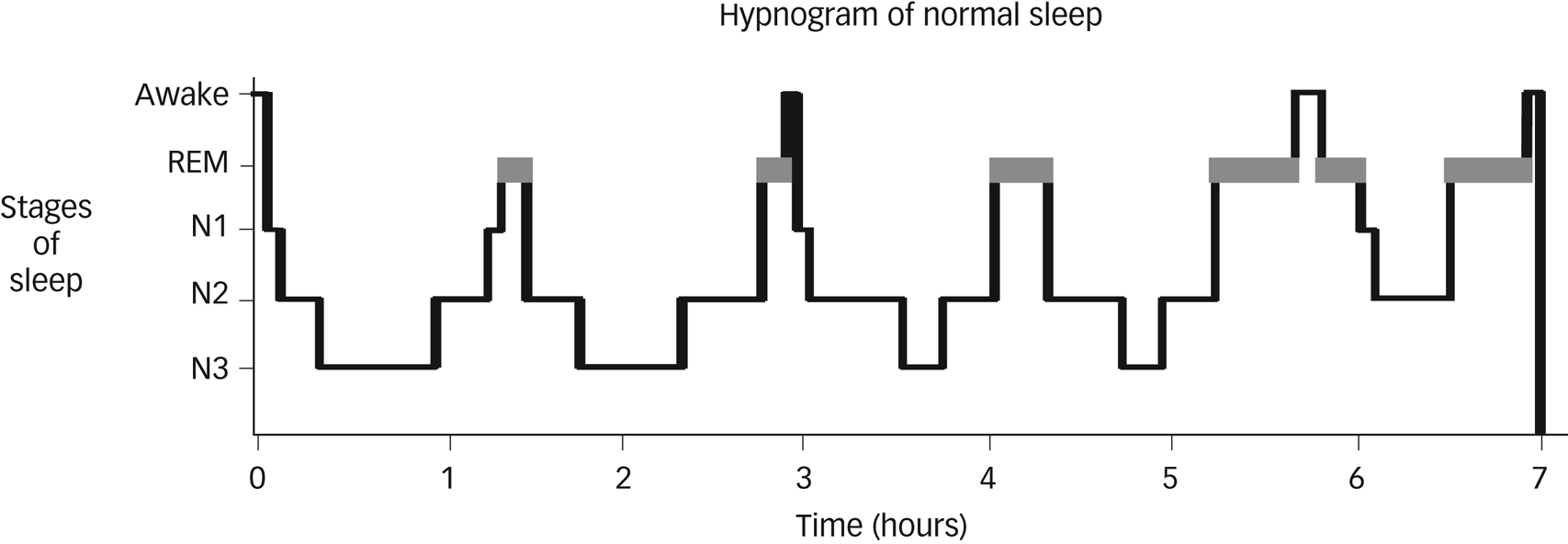

Fig. 3 Hypnogram of a 14-year-old male. Longer (more adult-like) sleep cycle duration (some sleep fragmentation). Non-rapid eye movement sleep is split into stages N1–N3. Courtesy of Dr Elizabeth A. Hill, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh. REM, rapid eye movement.

Sleep during childhood and adolescence

The duration of sleep, the duration of sleep cycles and the circadian rhythm differ between individuals, and vary during a person's lifetime. Newborns sleep most of the day and toddlers sleep for up to 12 h during the night, as well as having one or two naps during the day.Reference Bathory and Tomopoulos7 REM and NREM cycles occur every 50–60 min in children under the age of 8 years, and these cycles gradually change to every 90 min as the child develops. Night waking is normal for all children, but is typically very brief, with rapid return to sleep. The proportion of stage N3 SWS is higher and the amplitude of the delta waves is far larger in children compared with adults; this proportion continuously reduces throughout adolescence and into adulthood (see Figs 2 and 3).Reference Mindell, Owens and Carskadon1 During the final stages of puberty, there is a biological change in the circadian system whereby children fall asleep later and increase their total sleep time. This often coincides with a desire to stay up late at night to engage in more adult social activities. This delay in circadian phase leads to a delay in sleep onset,Reference Dahl and Lewin8 and may cause a lack of synchronicity between adolescent circadian rhythm and that of the parents and of societal structures (such as school timetables). These changes can lead to insufficient sleep, family discord and subsequent emotional difficulties.Reference Carskadon9 Sleep deprivation, particularly REM deprivation, in neonates and infants may have a permanent negative effect on development of neural circuitry of the primary sensory system, and of emotion, social learning and memory.Reference Penn and Shatz2

Affective disorders in adolescents

Major depressive disorder (MDD) in adolescence is characterised by a pervasive and persistent low or irritable mood10 and/or anhedonia, which can also be accompanied by low self-esteem.11 Adolescents with depression may report certain symptoms more often than adults, such as loss of energy, weight and appetite changes, and sleep difficulties, whereas adults report more anhedonia and concentration difficulties.Reference Rice, Riglin, Lomax, Souter, Potter and Smith12 Early and accurate detection and management of MDD is important because early onset can be a potent predictor of lifelong recurrent depression.Reference Carballo, Muñoz-Lorenzo, Blasco-Fontecilla, Lopez-Castroman, García-Nieto and Dervic13

Bipolar disorder is a chronic, typically relapsing condition, characterised by episodes of (hypo)mania and depression with a negative effect on overall functioning. In the DSM-IV14 and DSM-5,10 it has been separated into type 1, type 2, cyclothymia and not otherwise specified.10,14,Reference Nottelmann15 A number of specifiers have been used for bipolar disorder when it occurs in young people, including prepubescent, juvenile, childhood or adolescent bipolar disorder.10 Bipolar disorder in adolescence is more likely to exhibit rapid cycling and mixed states, and the symptoms are more likely to have a fluctuating intensity and duration, thereby reducing the likelihood of accurate diagnosis compared with adults.10

Adolescent-onset MDD and bipolar disorder often have a chronic, episodic course, and can be accompanied by long-term functional impairment.Reference Fernandez-Mendoza, Calhoun, Vgontzas, Li, Gaines and Liao16 Those affected have higher rates of substance misuse, poor academic attainment, interpersonal difficulties, poor sleep patterns and higher risk of suicide compared with healthy adolescents. These difficulties can negatively affect physical, emotional, cognitive and social development.Reference Fernandez-Mendoza, Calhoun, Vgontzas, Li, Gaines and Liao16–Reference Roberts, Roberts and Duong18

Sleep disorders

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3)Reference Medicine19 defines more than 70 sleep disorders classified into seven major categories, one of which is insomnia.Reference Medicine19 The DSM-510 describes ten sleep–wake disorders, and the ICD-1011 groups nonorganic sleep disorders into dyssomnias, parasomnias and nonpsychogenic disorders (see Table 1). When considering disordered sleep, it is worth noting that subjectively reported sleep correlates poorly with objective findings.Reference Bertocci, Dahl, Williamson, Iosif, Birmaher and Axelson20,Reference Chen, Burley and Gotlib21 For further information on specific sleep disorders, please refer to Table 2.

Table 1 Diagnostic entities in ICSD-3, DSM-5 and ICD-10

ICSD-3, International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition; NREM, non-rapid eye movement; REM, rapid eye movement.

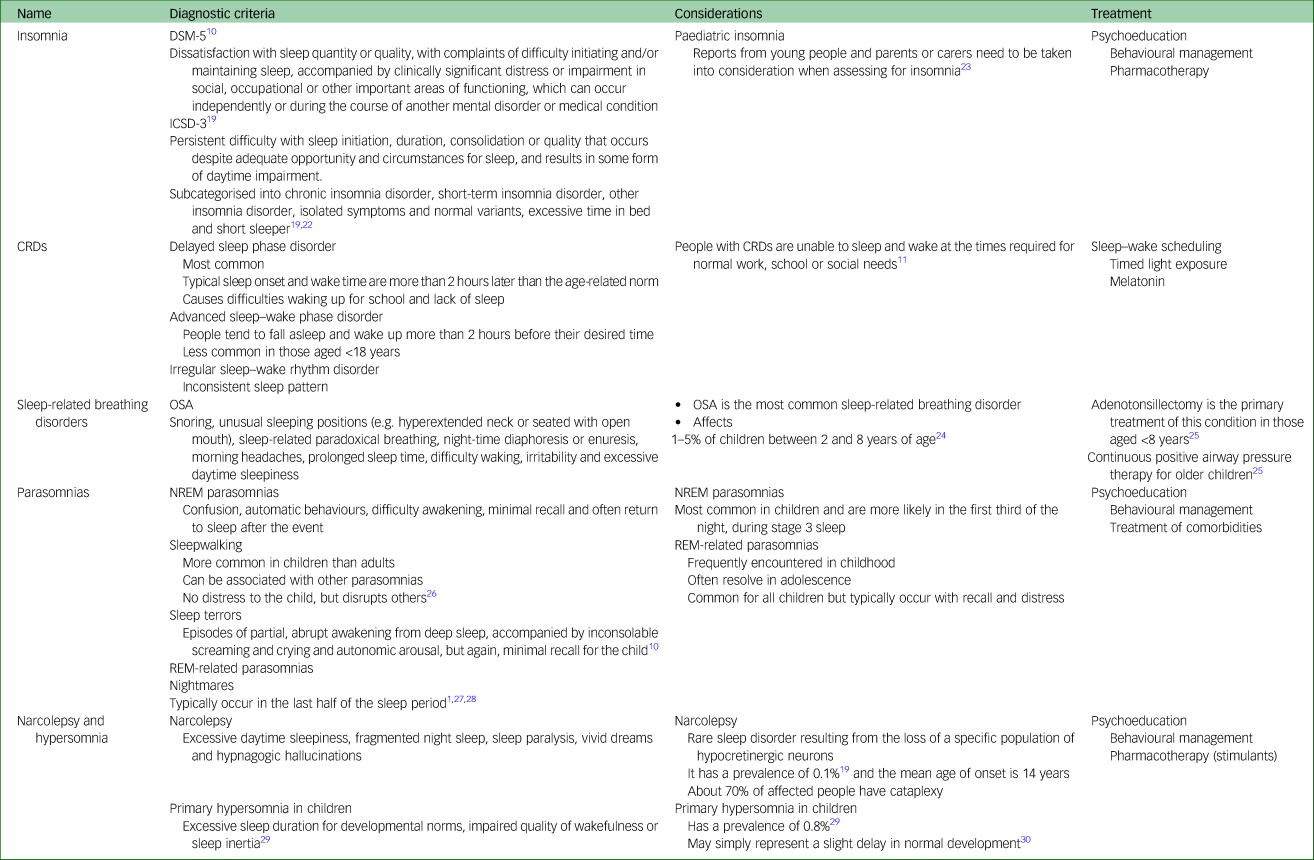

Table 2 Sleep disorders

ICSD-3, International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition; CRD, circadian rhythm disorder; OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea; NREM, non-rapid eye movement; REM, rapid eye movement.

Insomnia

The diagnostic criteria for insomnia in adults and young people are the same; however, in the younger population, the problems around initiating and maintaining sleep can also be reported by the carers. These difficulties are typically associated with bedtime resistance and behavioural change.Reference Bruni and Novelli23

Circadian rhythm disorders

The social zeitgeber theory posits that changes to the circadian rhythm can be linked to disruptions of bedtime, wake time or meal times.Reference Grandin, Alloy and Abramson31 Circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRDs) are caused by desynchronisation between the internal sleep–wake rhythms and the light–dark cycle, or a misalignment between the body clock and the person's external environment.

Sleep-related breathing disorders

Among the sleep-related breathing disorders, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is the most common and is primarily caused by enlarged tonsils and adenoids.

Parasomnias and nightmare disorders

Parasomnias are divided into two categories: REM and NREM. They affect up to 50% of childrenReference Carter, Hathaway and Lettieri27 and are a risk factor for the subsequent development of MDD in adulthood.Reference Byrne, Timmerman, Wray and Agerbo32 REM-related parasomnias, such as sleep paralysis or nightmare disorder, are frequently encountered in childhood and, like NREM parasomnias, they often resolve spontaneously in adolescence.Reference Mindell, Owens and Carskadon1,Reference Carter, Hathaway and Lettieri27,Reference Kazaglis and Bornemann28

Narcolepsy and hypersomnia

Narcolepsy is a rare sleep disorder caused by the loss of a specific population of hypocretinergic neurons. This condition has been associated with depression both in adultsReference Byrne, Timmerman, Wray and Agerbo32 and the paediatric population.Reference Ohayon33–Reference Plazzi, Clawges and Owens35 Primary hypersomnia may be transient or may represent a slight delay in normal development,Reference Steinsbekk and Wichstrom30 and has not been associated with affective psychiatric disorders in adulthood. Bouts of episodic hypersomnia, along with cognitive and behavioural changes, are part of the very rare condition of Kleine–Levin syndrome.

Sleep-related movement disorders

Sleep-related movement disorders, such as restless legs syndrome (RLS), periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) or the far less common condition of rhythmic movement disorder, are conditions that cause movement during or before sleep.

Sleep disorders and their relationship with mood

Behavioural pattern insomnia occurs more often in children and has been associated with symptoms of depression in preschoolers.Reference Steinsbekk, Berg-Nielsen and Wichstrom29 It is important to be mindful of the parent–child interaction around bedtime, and a thorough assessment often helps to identify the aetiology of the sleep problem. Children can become habituated into needing a bedtime story or other event as the associated condition to fall asleep. This can create sleep difficulties, such as when children wake through the night and are unable or unwilling to self-settle in its absence. Sleep difficulties can occur when parents struggle to implement boundaries or routines around bedtime in older children. Additionally, certain parental expectations that are not in line with the developmental stageReference Werner and Jenni36 and children's sleep needs might lead to their erroneous identification of disordered sleep, in particular the natural later bedtimes through puberty and teenage years.

Data from school-aged childrenReference Hodges, Marcus, Kim, Xanthopoulos, Shults and Giordani37 and adult research have shown an association between OSA and depression.Reference Byrne, Timmerman, Wray and Agerbo32,Reference Garbarino, Bardwell, Guglielmi, Chiorri, Bonanni and Magnavita38 OSA is more prevalent in people with bipolar disorder, both in adultsReference Kelly, Douglas, Denmark, Brasuell and Lieberman39 and adolescents,Reference Mieczkowski, Oduguwa, Kowatch and Splaingard40 but research in this field remains sparse.

Significant, intrusive and distressing parasomnia has been associated with suicidal thinkingReference Gau and Suen Soong41 and, in younger children (aged 12 years), with psychotic phenomena, albeit rarely.Reference Fisher, Lereya, Thompson, Lewis, Zammit and Wolke42 Adults with MDD and bipolar disorder are more likely to have experienced parasomnias, such as confusional arousal disorder, night terrors and sleepwalking, than the general population, but the nature of this association remains unclear given how common these symptoms are in children and are mostly benign, infrequent and self-limiting.Reference Ohayon, Guilleminault and Priest43

When frequent and intrusive, nightmares can occasionally result in daytime impairment and reduced quality of life, and are associated with psychological distress and symptoms of anxiety and depression.Reference Levin and Fireman44,Reference Krakow45 Sheaves et al found that high nightmare frequency followed by subsequent distress was positively associated with higher scores in difficulties, such as depression, among students.Reference Sheaves, Porcheret, Tsanas, Espie, Foster and Freeman46

Narcolepsy has been associated with depression in adultsReference Byrne, Timmerman, Wray and Agerbo32 and in the paediatric population.Reference Ohayon33–Reference Plazzi, Clawges and Owens35 Additionally, there are no biomarkers for Kleine–Levin syndrome, its aetiology is debated, there is spontaneous remission and one study suggested that young people with a history of Kleine–Levin syndrome may experience depression later in life.Reference Groos, Chaumereuil, Flamand, Brion, Bourdin and Slimani47

CRDs have a higher prevalence in adults with bipolar disorder than the general population,Reference Melo, Abreu, Linhares Neto, de Bruin and de Bruin48,Reference Talih, Gebara, Andary, Mondello, Kobeissy and Ferri49 with a significant association with a younger onset of bipolar disorder.Reference Takaesu, Inoue, Murakoshi, Komada, Otsuka and Futenma50 CRDs are also risk factors for developing MDD in adults,Reference Byrne, Timmerman, Wray and Agerbo32 and have been associated with depressive symptoms in adolescents.Reference Saxvig, Pallesen, Wilhelmsen-Langeland, Molde and Bjorvatn51

RLS and PLMD have been associated with depression in adults when severe and sleep disruptive.Reference Byrne, Timmerman, Wray and Agerbo32 In children and young people, RLS has a prevalence of 2–4%Reference Xue, Liu, Ma, Yang and Li52 and has been associated with depression, although to a lesser extent, and usually the condition is milder in younger adults.Reference Angriman, Cortese and Bruni53 Adolescents with PLMD also appear to display more depressive symptoms.Reference Frye, Fernandez-Mendoza, Calhoun, Vgontzas, Liao and Bixler54

Mood disorders and their relationship with sleep

Disturbed sleep is a core feature of a depressive episode,Reference Skapinakis, Rai, Anagnostopoulos, Harrison, Araya and Lewis55 may occur in the prodromal periodReference Lovato and Gradisar56,Reference Sivertsen, Harvey, Lundervold and Hysing57 and/or be a residual symptom of depression.Reference Skapinakis, Rai, Anagnostopoulos, Harrison, Araya and Lewis55 Conversely, mood disturbance is listed as one of the functional impairment criteria for insomnia disorder.

In the general teenage population, insomnia is associated with mental health difficulties later in life.Reference Gregory, Caspi, Eley, Moffitt, O'Connor and Poulton58 Disturbed sleep confers an increased risk of subsequent bipolar.Reference Faedda, Baldessarini, Glovinsky and Austin59–Reference Ritter, Marx, Bauer, Lepold and Pfennig63 Wakefulness in bedReference Lovato and Gradisar56 and a shorter duration of sleepReference Sivertsen, Harvey, Lundervold and Hysing57 can be regarded as aetiological factors for depression.Reference Buysse, Angst, Gamma, Ajdacic, Eich and Rossler64–Reference McGlinchey, Reyes-Portillo, Turner and Mufson67 Sleep difficulties can precede affective episodesReference Faedda, Baldessarini, Glovinsky and Austin59,Reference Ritter, Höfler, Wittchen, Lieb, Bauer and Pfennig61–Reference Ritter, Marx, Bauer, Lepold and Pfennig63,Reference Baglioni, Battagliese, Feige, Spiegelhalder, Nissen and Voderholzer68,Reference Pancheri, Verdolini, Pacchiarotti, Samalin, Delle Chiaie and Biondi69 and other mental health difficultiesReference Gregory, Caspi, Eley, Moffitt, O'Connor and Poulton58 by several years in young people. Aspects of the sleep architecture of insomnia, such as reductions in SWS, low spindle activity or changes in REM, are also associated with internalising behaviours.Reference Blake, Trinder and Allen70

In young people who are currently depressed, disturbed sleep incorporating sleep continuity problems,Reference Murray, Murphy, Palermo and Clarke17 wakefulness in bed and increased sleep-onset latency is common. Decreased sleep efficiency, short sleep duration, daytime sleepiness, non-restorative sleep, hypersomnia and irregular sleep–wake rhythm are also common.Reference Rice, Riglin, Lomax, Souter, Potter and Smith12,Reference Murray, Murphy, Palermo and Clarke17,Reference Bertocci, Dahl, Williamson, Iosif, Birmaher and Axelson20,Reference Steinsbekk, Berg-Nielsen and Wichstrom29,Reference Lovato and Gradisar56,Reference Sivertsen, Harvey, Lundervold and Hysing57,Reference Liu, Buysse, Gentzler, Kiss, Mayer and Kapornai71–Reference Orchard, Gregory, Gradisar and Reynolds75 Sleep difficulties are associated with higher depression severity and recurrence;Reference Emslie G, Armitage, Weinberg, Rush, Mayes and Hoffmann76 greater fatigue, suicidal ideation, physical complaints and pain;Reference Murray, Murphy, Palermo and Clarke17 and decreased concentration.Reference Urrila, Karlsson, Kiviruusu, Pelkonen, Strandholm and Marttunen73,Reference Emslie, Kennard, Mayes, Nakonezny, Zhu and Tao77 There is evidence that sleep quality, total sleep time and sleep microarchitecture can predict new onset and recurrence of depression.Reference Armitage, Hoffmann, Emslie, Weinberg, Mayes and Rush78

Robust adult data and preliminary data in young people suggests that sleep problems can be encountered in all phases of bipolar disorder,Reference Salvatore, Ghidini, Zita, Panfilis, Lambertino and Maggini79 can be associated with psychosocial impairment and can play a role in predicting mania and depression.Reference Lunsford-Avery, Judd, Axelson and Miklowitz80–Reference Lewis, Gordon-Smith, Forty, Di Florio, Craddock and Jones82 Sleep disturbances among adolescents with bipolar disorder can have an effect on the severity of depressiveReference Lunsford-Avery, Judd, Axelson and Miklowitz80,Reference Gershon and Singh81 and manic symptoms, are associated with academic and social impairment during recovery,Reference Lunsford-Avery, Judd, Axelson and Miklowitz80 and can be a poor prognostic indicator. Young people with bipolar disorder show a range of sleep difficulties, including delayed sleep onset, insomnia, hypersomnia and difficulties waking up in the morning. They can also present with difficulties maintaining a regular rhythm, longer naps during the day, more night-time wakings, a greater total time awake during the night and nightmare disorder.Reference Lunsford-Avery, Judd, Axelson and Miklowitz80,Reference Stanley, Hom, Luby, Joshi, Wagner and Emslie83–Reference Diler, Goldstein, Hafeman, Merranko, Liao and Goldstein86 Nightmares appear to augment the risk of suicide, and insufficient sleep duration has been associated with self-injurious behaviours.Reference Roybal, Chang, Chen, Howe, Gotlib and Singh84 Mania has been associated with decreased need for sleep in young people;Reference Harvey, Talbot and Gershon87 however, in adolescents, mania also appears to be linked to a broader sleep disturbance,Reference Faedda, Baldessarini, Glovinsky and Austin59 including variable sleep duration and unstable morning routines.Reference Lunsford-Avery, Judd, Axelson and Miklowitz80 Sleep disturbance does not appear to differentiate between types of bipolar disorders, being as common, for instance, in bipolar disorder not otherwise specified as in bipolar disorder type 1.Reference Baroni, Hernandez, Grant and Faedda88 Disturbed sleep is seen more often in the children of parents with bipolar disorder than in healthy controls.Reference Ritter, Höfler, Wittchen, Lieb, Bauer and Pfennig61,Reference Sebela, Novak, Kemlink and Goetz89 One study of children whose parents were diagnosed with bipolar disorder showed shorter time to onset of sleep and longer duration on actigraphy, with opposite subjectively reported experiences.Reference Jones, Tai, Evershed, Knowles and Bentall90 This is in accordance with a second study showing that people deemed to be at high risk of developing bipolar disorder, either through family history of bipolar disorder or personal history of severe depression and subthreshold mania symptoms, have shown a longer duration for sleep onset, but also higher levels of sleep specific worries.Reference Ritter, Marx, Lewtschenko, Pfeiffer, Leopold and Bauer85 Depressed youth with bipolar disorder are significantly more likely to be affected by daytime sleepiness and hypersomnia than young people with unipolar depression.Reference Diler, Goldstein, Hafeman, Merranko, Liao and Goldstein86

Mechanism of the association between mood disorders and sleep

Maladaptive thinking processes, such as cognitive inflexibility, attention bias by selectively focusing on negative information, misperception of sleep deficit, rumination and worry, may underlie insomnia, depression and bipolar disorder in adolescence.Reference Blake, Trinder and Allen70 These processes may trigger autonomic arousal and the reinforcement of negative cognitions. Similarly, abnormalities of circadian rhythm, perhaps mediated by genetic vulnerability via polymorphisms of serotonin, dopamine and circadian clock genesReference Ankers and Jones60,Reference Mansour, Monk and Nimgaonkar91 or dysfunction in the white matter integrity, could also play a role in the aetiology of these conditions.Reference Bollettini, Melloni, Aggio, Poletti, Lorenzi and Pirovano92 Disruption of the corticolimbic circuitryReference Blake, Trinder and Allen70 may be a consequence of insomnia, and may impair affective reactivity and regulation.Reference Dahl93 Dysregulation of reward/approach related brain function,Reference Blake, Trinder and Allen70,Reference Casement, Keenan, Hipwell, Guyer and Forbes94 hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation and elevated inflammatory cytokines may also contribute to both psychopathology and sleep disturbance.Reference Blake, Trinder and Allen70 Disruptions to the circadian rhythm have been postulated to contribute to the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder.Reference Bradley, Webb-Mitchell, Hazu, Slater, Middleton and Gallagher95 Genetic commonality between sleep and impulsivity and anger/frustration has also been described.Reference Miadich, Shrewsbury, Doane, Davis, Clifford and Lemery-Chalfant96 Antidepressants, particularly those with noradrenergic or dopaminergic mechanisms, may induce or aggravate insomnia. Electronic media use among adolescents, particularly at night-time, may be related to sleep disturbance and higher levels of depressive symptoms,Reference Lemola, Perkinson-Gloor, Brand, Dewald-Kaufmann and Grob97 in which a sleep debt developed over school days is paid back at the weekend.Reference Wittmann, Dinich, Merrow and Roenneberg98

Interventions for mood disorders and sleep problems

Non-pharmacological interventions for depression and sleep problems

Psychoeducation, consistent sleep–wake schedules and tailored interventions for addressing sleep problems should play an important role in the prevention and treatment of mental health difficulties, at any age. Concomitantly addressing sleep problems can lead to an increased remission rate of depression.Reference McGlinchey, Reyes-Portillo, Turner and Mufson67,Reference Clarke and Harvey99

Cognitive–behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) has a strong evidence base for decreasing insomnia severity.Reference Blake, Trinder and Allen70,Reference Clarke, McGlinchey, Hein, Gullion, Dickerson and Leo100 There have been a number of studies of CBT-I in young people with comorbidities (e.g. Moore et alReference Moore, Phillips, Palermo and Lah101); two randomised controlled trials in young people not selected on the basis of comorbidity have shown a persistent benefit in sleep onset, latency, efficiency and anxiety, but not in total sleep time.Reference Paine and Gradisar102,Reference Schlarb, Bihlmaier, Velten-Schurian, Poets and Hautzinger103 Internet-delivered CBT-I has also been examined. Recent large, randomised controlled trials, one of which targeted university students,Reference Freeman, Sheaves, Goodwin, Yu, Nickless and Harrison104 have shown a benefit in sleep and a number of mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety and psychotic phenomena.Reference Freeman, Sheaves, Goodwin, Yu, Nickless and Harrison104,Reference Christensen, Batterham, Gosling, Ritterband, Griffiths and Thorndike105

Transdiagnostic sleep and circadian intervention collates established sleep management strategies,Reference Harvey106 and has been shown to exert a sustained beneficial effect on eveningness circadian preference in adolescents.Reference Dong, Dolsen, Martinez, Notsu and Harvey107 Post hoc analysis revealed that the initial broader health benefits were not maintained (compared with psychoeducation) at 6 months.Reference Dong, Dolsen, Martinez, Notsu and Harvey107,Reference Dong, Gumport, Martinez and Harvey108

Pharmacological intervention for depression and sleep problems

Many patients with depression enter REM stage quicker and have less NREM sleep in the first sleep cycle. Antidepressants typically alter sleep in the opposite direction.Reference Wichniak, Wierzbicka, Walęcka and Jernajczyk109 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the antidepressants of choice in children and young people. It is important that sleep effects are considered in the discussion of positives, negatives and gaps in knowledge that are required to allow an informed decision of whether and when to use medication alongside psychosocial interventions for treating depression. SSRIs are known to increase REM latency and SWS, reduce REM sleep and sleep continuity, and may also induce nightmares, cause enhanced dreaming and lead to changes in dream content.Reference Anderson and Bradley65,Reference Wichniak, Wierzbicka, Walęcka and Jernajczyk109–Reference Sharpley and Cowen114 Upon stopping the treatment, rebound REM sleep is known to occur.Reference Wilson and Argyropoulos110 SSRIs can increase the risk of aggravating RLS, or induce RLS or PLMD symptoms.Reference Kolla, Mansukhani and Bostwick115

Melatonin

Melatonin is often used for children with sleep-onset insomnia or delayed sleep phase syndrome and neurodevelopmental disorders. High doses of melatonin are rarely needed for managing insomnia. Behavioural strategies should be used as a first-line treatment.Reference Gringras, Nir, Breddy, Frydman-Marom and Findling116–Reference Wilson, Anderson, Baldwin, Dijk, Espie and Espie118 Adults with affective disorders have been found to have abnormalities in the timing and amplitude of biological rhythms, including abnormal patterns of melatonin secretion.Reference Germain and Kupfer119 Differences in the level of melatonin and in the pattern of its production have been described in adults with bipolar disorder across mood states.Reference Nurnberger JI, Adkins, Lahiri, Mayeda, Hu and Lewy120 A recent study suggested that melatonin levels are related to social and occupational functioning in young people with affective disorders. The putative role of melatonin in the treatment of depression in young people is an exciting prospect.Reference Carpenter, Abelmann, Hatton, Robillard, Hermens and Bennett121

Non-pharmacological interventions for bipolar disorder and sleep

Regulating sleep and maintaining consistent sleep–wake schedules in young people with bipolar disorder improves outcomes, and potential affective relapses can be prevented and/or minimised. This may be enacted via psychoeducation, the development of consistent sleep and wake times and routines, relaxation procedures, and reinforcement of good sleep habits,Reference Schwartz and Feeny122 chronotherapyReference Robillard, Naismith, Rogers, Ip, Hermens and Scott123 or CBT-I.Reference Harvey, Mullin and Hinshaw124

Pharmacological interventions for bipolar disorder and sleep

The use of psychotropic medication in children and young people is only advisable when a clear diagnosis of bipolar disorder has been made, and should not be used solely for addressing sleep. Improved sleep is associated with pharmacologically mediated improvement in mood symptoms in adolescents,Reference Roybal, Chang, Chen, Howe, Gotlib and Singh84 but it is worth considering whether the effect of bipolar psychotropics on sleep mediates some of these changes. Olanzapine and quetiapine have a significant impact on sleep duration in younger people with bipolar disorder.Reference Ritter, Marx, Lewtschenko, Pfeiffer, Leopold and Bauer85 Antipsychotics, including olanzapine, quetiapine and ziprasidone, have been shown in the adult population to increase the duration of sleep continuity, increase total sleep time and sleep efficiency, increase REM latency and SWS, decrease stage 2 sleep spindle density and reduce the amount of REM sleep.Reference Göder, Fritzer, Gottwald, Lippmann, Seeck-Hirschner and Serafin125

The increased risk of metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder also increases the risk of OSA in adolescents.Reference Mieczkowski, Oduguwa, Kowatch and Splaingard40 Another study suggested a possible relationship between the use of medication and enuresis,Reference Baroni, Hernandez, Grant and Faedda88 which could further affect the sleep.

Research direction

There are a number of challenges in the field of sleep research in MDD and bipolar disorder. First, most studies are cross-sectional, with an unclear timeline between the onset of the affective disorder, that of sleep difficulties and the short- and long-term complications.Reference Stanley, Hom, Luby, Joshi, Wagner and Emslie83 There is still limited objective sleep assessment with polysomnography, and many studies report subjective sleep via self-/parent report or actigraphy without, for example, screening for specific sleep disorders or using polysomnography. The parent–child agreement for psychiatric disorders is low and, wherever possible, the children and young people should be consulted about their sleep directly; depression and bipolar disorder are no exception.Reference Roybal, Chang, Chen, Howe, Gotlib and Singh84,Reference Achenbach, McConaughy and Howell126 Terms such as sleep disorders and sleep difficulties are used interchangeably, and there is a need for greater precision with the use of, for example, insomnia disorder or CRD. Additionally, there seems to be a very high reliance on assessment questionnaires for diagnosing sleep problems and sometimes even affective disorders. Over the years, there have been inconsistent findings in the studies for depression in children and young people,Reference Ivanenko, Crabtree and Gozal127 as study designs vary a great deal.

The number of patients included in trials for bipolar disorder tends to be relatively low, which might be linked to the relatively low prevalence in children and adolescents and the subsequent recruitment challenge. Some studies seem to focus on one type of bipolar disorder and do not include the full spectrum of disorders, which might leave out important information.Reference Baroni, Hernandez, Grant and Faedda88 Findings vary across studies because of differences not only in the sleep measurement, but also sampling; some studies focus on children who have been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, whereas others include children whose parents have an affective disorder.Reference Gershon and Singh81 There is also a high variability of the age range, as there is no consensus on the age of onset of paediatric bipolar disorder; some papers have included participants of 5 years of age,Reference Baroni, Hernandez, Grant and Faedda88 whereas others have focused on prepubescentsReference Lofthouse, Fristad, Splaingard and Kelleher128 or adolescents.Reference Lunsford-Avery, Judd, Axelson and Miklowitz80 One has to consider the importance of brain maturation and expected sleep changes that occur in these stages of life, as well as the beliefs around sleep within the family.

An important direction for future research would be developing a robust study design that allows a longer-term evaluation of the symptoms of a bigger cohort, objective and subjective standardised measures of sleep and mood, screening for comorbid sleep disorders, collecting collateral information and focusing on behavioural interventions for sleep, such as CBT-I.

Conclusions

The relationship between sleep difficulties and mood in children and young people is complex. Sleep problems are reported long before the onset, during and sometimes after, an episode of unipolar depression or bipolar disorder, and can play an important role in their presentation. The prevalence of sleep disorders, such as insomnia, CRDs and sleep apnoea, in depression and bipolar disorder is higher than in the general population, but often these diagnoses are missed and specific treatment not offered. A multi-modal approach would include the treatment of both the affective and specific sleep disorder. ‘Sleep disturbance’ is not a diagnosis. There is a need for further longitudinal studies with subjective and objective sleep measures to improve therapy and the nature of the relationship between mood and sleep. Of most importance is the impact of specific treatment for sleep disorders on the long-term outcome of affective disorders. Clinicians need to know if better nights reliably lead to better days.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Elizabeth A. Hill (Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh) for assistance with hypnograms.

Author contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception of the work, have revised it critically for important intellectual content, have offered the final approval of the version to be published and are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. In addition, M.C., K.N.A. and S.W. made substantial contributions to the design of the work and drafted the paper. Furthermore, M.C. also acquired and interpreted the data.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1076.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.