It is estimated that around 53 337 people have been detained under the Mental Health Act (MHA) between 2021 and 2022.1 This has a major impact not only on the lives of those detained under the MHA, but also their family members or friends who support them (‘carers’).Reference Stuart, Akther, Machin, Persaud, Simpson and Johnson2 Previous research on the experiences of carers of patients treated under the MHA showed that most felt isolated and unsupported.Reference Stuart, Akther, Machin, Persaud, Simpson and Johnson2,Reference Jankovic, Yeeles, Katsakou, Amos, Morriss and Rose3 Carers left without support are at risk of developing mental and physical health conditions.Reference Yesufu-Udechuku, Harrison, Mayo-Wilson, Young, Woodhams and Shiers4 However, if carers felt supported by services, their caregiving experience may include positive aspects, such as a sense of fulfilment from supporting their family member/friend, enhanced self-esteem and improvements in the relationship with their family member/friend.Reference Kulhara, Kate, Grover and Nehra5 Carers can also influence a patient's outcomes. More positive caregiver views around patient treatment were associated with greater symptom improvement among patients.Reference Giacco, Fiorillo, Del Vecchio, Kallert, Onchev and Raboch6 Improving carer and, consequently, patient outcomes could contribute to substantial economic savings. Currently, carers save the economy £162 billion per year in their support of patients.7 Therefore, it is integral that carers receive appropriate support.

Support during involuntary hospitalisation

Carer support groups (often led by professionals or other carers (‘peers’)) are currently available and have been beneficial for carers.Reference Worrall, Schweizer, Marks, Yuan, Lloyd and Ramjan8 Studies examining the impact of these support groups focus predominantly on carers of out-patients with severe mental health conditions.Reference Worrall, Schweizer, Marks, Yuan, Lloyd and Ramjan8 However, the involuntary hospital admission of a loved one can be an extremely distressing and traumatic experience for carers,Reference Jankovic, Yeeles, Katsakou, Amos, Morriss and Rose3,Reference Dixon, Stone and Laing9 and the support needs of this carer group may vary significantly from carers of out-patients. There are numerous legal processes for these carers to navigate, depending on a patient's diagnosis, history or sectioning. Additionally, involuntary admission often comes following difficult circumstances and, at times, conflict between patients and their carers. Carers may also experience feelings of guilt surrounding their loved one's detention.Reference Stuart, Akther, Machin, Persaud, Simpson and Johnson2,Reference Jankovic, Yeeles, Katsakou, Amos, Morriss and Rose3 As such, there may be a strong need for emotional support during this difficult time. The most recent MHA review has recognised the need to support these carers when a family member/friend is involuntarily admitted to hospital under the MHA, recommending that support be offered to this group.10 Therefore, understanding how these carers can be supported effectively is integral. To obtain this understanding, further information from carers about the type of support they want to receive during their family member's/friend's involuntary hospital admission is needed.

Currently, no study has explored the specific support needs of carers of people who have been involuntarily admitted to hospital under the MHA. An increased understanding of carers’ needs and experiences of support could inform the development of a support programme to improve their well-being. To address this gap, the current study aimed to explore: (a) how carers report being supported when their family member/friend is involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric hospital, and (b) how carers think this support could be improved.

Method

Design

This was a qualitative, semi-structured interview study using a positivist framework to inform the design and analysis of the study.Reference Su, C, AL and G11,Reference Park, Konge and Artino12 In line with this framework, a topic guide was used to structure the interviews and patterns in the data were identified through thematic analysis, using the approach developed by Braun and Clarke.Reference Braun and Clarke13 Codes and themes were systematically identified with a hybrid deductive–inductive approach, based on previous literature examining support for carersReference Heumann, Janßen, Ruppelt, Mahlke, Sielaff and Bock14 and data obtained within the current study.Reference Su, C, AL and G11,Reference Braun and Clarke13,Reference Thomas15

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee 3 (reference: 21/WS/0098). The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelinesReference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig16 were used to report on the methods and results of this study.

Participant recruitment

Participants were eligible to take part in the current study if they were a family member or friend with experience of supporting someone involuntarily treated in a psychiatric hospital within the past 10 years, were aged 18 years or older and had the capacity to consent.

A sample size of around 20 interviews has been suggested as sufficient to achieve thematic data saturation for an interview study using thematic analysis.Reference Guest, Bunce and Johnson17,Reference Braun and Clarke18 Therefore, we aimed to recruit a minimum of 20 carers to gain an in-depth understanding of their experience of support during their family member's/friend's involuntary hospital admission and any further support they would have liked during this time. Participants were recruited with a purposive sampling technique,Reference Palinkas, Horwitz, Green, Wisdom, Duan and Hoagwood19 considering their geographical location (Devon, Coventry and Warwickshire, and East London), gender and ethnic group to obtain diversity in the experiences of support.

Carers were identified through National Health Service (NHS) records and approached by the clinical team at each participating site (Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Partnership Trust (CWPT), East London NHS Foundation Trust (ELFT) and Devon Partnership NHS Trust (DPT)). They were also identified through carer groups and flyers provided in NHS facilities at each site, which asked carers to self-refer for participation. Demographic details of carer recruits were regularly monitored and discussed with both lived experience and professional groups involved in this study, who offered suggestions on ways to obtain a more diverse sample. From these suggestions, clinical staff discussed the study with carer communities frequented by those from typically underrepresented groups (e.g. minority ethnic groups). Lived experience and professional members who were themselves part of an underrepresented group also discussed the study with personal contacts and carer groups they attended. Participants received a brief overview of the study. Those who agreed to take part were contacted by the research team via either telephone or email, to arrange a suitable time for interview. Participants were paid £25 for taking part. Written or verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants. No participants dropped out once they had consented.

Procedure

All participants were interviewed by the study coordinator (I.W., a female postdoctoral research fellow with a background in health psychology), which they were informed of before their interview. The interviews were conducted online via Microsoft Teams (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA; see https://www.microsoft.com/en-gb/microsoft-teams/download-app). Interviews were conducted one-to-one with the participant and I.W. There was no relationship established between I.W. and participants before interview, and no repeat interviews were carried out. Field notes were made by I.W. after each interview, to aid analysis. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment and/or correction.

A semi-structured topic guide was used to guide the interviews. This topic guide was developed by the research team in co-production with a lived experience advisory panel (LEAP) comprising carers with experience of supporting someone treated under the MHA. These LEAP members also helped to co-produce participant-facing documents. The topic guide asked participants about their experience of receiving support, what support they would have liked during their family member's/friend's involuntary hospital admission and the potential benefits and challenges of carer support.

All interviews were audio-recorded through Microsoft Teams and transcribed verbatim by an external transcription company (Dictate2Us), omitting any personal data. The company respected the same standards of confidentiality used in the University of Warwick and NHS.

Analysis

In line with the positivist framework,Reference Su, C, AL and G11,Reference Park, Konge and Artino12 the interview data were analysed systematically with deductive–inductive thematic analysis. A deductive coding framework was generated by a member of the research team (A.G-M., a female research assistant with a background in biomedical science), using findings obtained from previous literature,Reference Heumann, Janßen, Ruppelt, Mahlke, Sielaff and Bock14 with input from I.W. and D.G. (a male professor with a background in psychiatry). The design of this deductive coding framework was also discussed with the LEAP, with feedback being incorporated into the framework by the authors. The transcripts were then systematically coded according to this framework. Each transcript was also coded openly to explore and categorise any additional themes or subthemes found. Interviews were coded independently by four researchers (I.W.; A.G-M.; N.O., a female volunteer researcher with a background in medicine; and E.L.R.T., a female postdoctoral student with a background in psychology) to examine inter-coder reliability. This analysis was facilitated by NVivo version 12.0 for Windows (Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA; see https://lumivero.com/resources/support/getting-started-with-nvivo/download-and-activate-nvivo/). The codebook was refined through several discussions among all authors. Participants did not provide feedback on the codebook. However, six carers from the LEAP were sent the refined codebook and provided further feedback, which was incorporated by authors.Reference Giacco, Chevalier, Mcnamee, Barber, Shafiq and Wells20 The final codebook represents a formal framework that could be applied to further research examining carer support or toward the development of a carer support programme.Reference Su, C, AL and G11,Reference Park, Konge and Artino12

Results

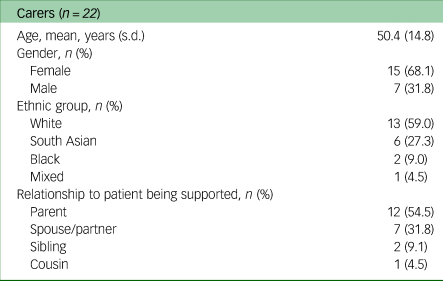

Twenty-two carers across three sites took part in an online one-to-one interview between November 2021 and August 2022 (seven from DPT, seven from CWPT and eight from ELFT). Interviews lasted between 20 and 75 min. Most participants were female (68.1%), White (59%) and a parent of someone involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric hospital (54.5%). The mean age was 50 years. Participant characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Summary of participant characteristics

Thematic data analysis

Four overarching themes were identified from the thematic analysis: theme 1, heterogeneity in the current support for carers; theme 2, information about mental health and mental health services; theme 3, continuous support; and theme 4, peer support and guidance. Within each theme are various associated subthemes. An overview of the themes and subthemes identified are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2 Overview of themes and subthemes

Heterogeneity in the current support for carers

Carers described their experience of support during their family member's/friend's involuntary hospital treatment and the impact that this support had on their well-being. The support received appeared to be heterogeneous, coming from various sources, including other family members, professionals and carers with previous experience of supporting someone who had been involuntarily admitted to hospital (‘peers’). Supporting quotes can be found in Table 3.

Table 3 Theme 1: heterogeneity in the current support for carers

Type of support received

Although there were some similarities in the type of support received across participants, this support appeared to vary with regard to the participant or person providing support (e.g. peers, family members or professionals). Most participants reported receiving some information and advice around their role in the care of their family members/friends during involuntary hospital admission. Some participants had been signposted to relevant services and contacts by peers, which was initially unknown to these participants (Table 3, quotes 1–4).

Several participants also described receiving information from professionals, such as social workers and doctors. This information primarily focused on patient and carer rights, including relevant MHA sections, the treatment process in psychiatric hospitals and a patient's right to a mental health tribunal (Table 3, quotes 5–7).

Some participants reported receiving support regarding their feelings around their family member's/friend's involuntary hospital admission, often provided by their family members, friends or peers. By communicating with these people, participants felt able to offload the burden felt around caring for their family member/friend (Table 3, quotes 8–10).

In some cases, participants also discussed matters unrelated to their family member/friend, with the reassurance that someone was available to talk when needed (Table 3, quotes 11–13).

However, a few participants did not receive support during their family member's/friend's involuntary admission. Some participants reported that they were not offered support (Table 3, quotes 14–16), or that the support offered did not fit their schedule, making it impossible to receive (Table 3, quote 17). Others reported not receiving support because of feelings of privacy or shame around their situation (Table 3, quotes 18 and 19).

Impact of support

On receiving support, participants described feeling understood and validated in their experience, particularly as a result of peer support. They reported feeling a deep understanding and unspoken bond with peers because they had gone through a similar experience (Table 3, quotes 20–23).

Some participants also felt reassured by peers’ depictions of their more positive experiences of care, such as their family member's/friend's improvement. This reassurance increased participants’ feelings of hope for their own family member's/friend's recovery (Table 3, quotes 24 and 25).

A few participants also described feeling reassured by peers’ negative experiences of care, which appeared to change their outlook on their own situation, feeling that their situation was perhaps not as bad as others (Table 3, quotes 26–28).

Information about mental health and mental health services

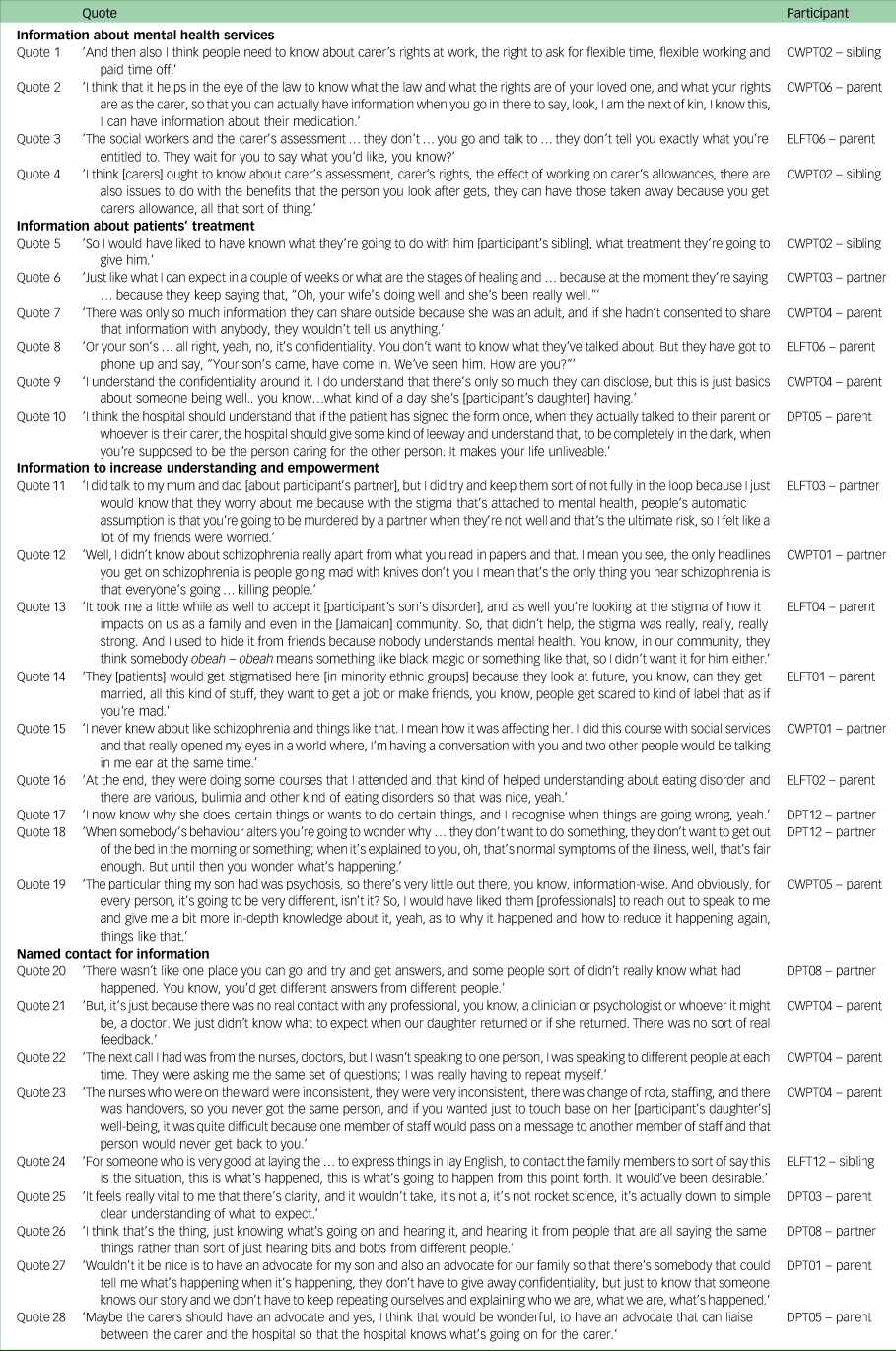

Although most participants did receive support during their family member's/friend's hospital admission, they identified other areas where they would have benefitted from further support. Specifically, participants wanted to receive further information about mental health services, including treatment provided to patients by these services, and for a consistent, named contact to provide this type of information. Supporting quotes can be found in Table 4.

Table 4 Theme 2: information about mental health and mental health services

Information about mental health services

Most participants felt that they needed more information about mental health services, including legal information relevant to their family member/friend and to them as a carer (Table 4, quote 1). It was reported that receiving information about their rights could help carers access other important information that was legally available to them (Table 4, quote 2).

Participants also reported needing information about the practical support they could receive during their family member's/friend's treatment, including carer's assessment and carer's allowance. Participants stated that this information is not made readily available to carers currently (Table 4, quote 3). Participants also felt it was important for carers to know about the potential impact of carer's allowance on their work and finances (Table 4, quote 4).

Information about patients’ treatment

Most participants reported wanting to receive more information about their family member's/friend's treatment options, how their treatment was going and what to expect during their treatment (Table 4, quotes 5 and 6). However, some participants felt that patient confidentiality was a barrier to the provision of this information (Table 4, quotes 7 and 8). Professionals must maintain patient confidentiality and thus cannot provide certain information to their carers unless patients consent to that information being shared. Most participants were aware of this, but felt that more basic information, such as information on their family member's/friend's general behaviour and well-being during their hospital stay, should be made available to carers without the need for consent (Table 4, quotes 8–10).

Information to increase understanding and empowerment

Participants and other family members/friends often had misconceptions about their patient's disorder stemming from a lack of awareness, which was often influenced by mental health stigma (Table 4, quotes 11 and 12). This had an impact on the way they felt toward their patient, and seemed particularly prominent within minority ethnic groups (Table 4, quotes 13 and 14).

Participants who received more information about their family member's/friend's condition reported gaining a better understanding of their loved one's experiences (Table 4, quotes 15–18). Those who did not receive such information reported wanting this information to feel more equipped in supporting their family member/friend by increasing their awareness of potential triggers (Table 4, quote 19).

Named contact for information

Participants reported receiving inconsistent or incomplete information about their family member's/friend's hospital treatment ( Table 4, quotes 20 and 21). They also described having to repeat information about their family member/friend to various professionals, noting a supposed lack of communication across the clinical team (Table 4, quotes 22 and 23). This unpredictability around the information communicated caused uncertainty and confusion among participants.

Because of this, participants reported wanting a specific person to share clear, comprehensive information between carers and hospital staff. Having this could ensure that the information received by both parties is accurate (Table 4, quotes 24–26).

Some participants felt that a separate advocate working specifically for carers could help to ensure that accurate information is communicated consistently between carers and the mental health service (Table 4, quotes 27 and 28).

Continuous support

During their family member's/friend's involuntary treatment, participants reported wanting a formal support service where they can express their emotions. Participants also consistently reported the need for this support to be provided by a single, continuous person. Supporting quotes can be found in Table 5.

Table 5 Theme 3: continuous support

Emotional support and reassurance

Participants described the experience of their family member's/friend's involuntarily hospital admission as distressing and traumatic (Table 5, quotes 1 and 2). Although some participants reported receiving emotional support during their family member's/friend's involuntary admission, others described not receiving this type of support at all (Table 5, quote 3). As a result, they reported needing a support service where they could receive regular check-ins and reassurance (Table 5, quotes 4–7).

Any support service offered to carers needs to be non-judgemental. One participant reported being judged for sharing his feelings because of his gender, which had a detrimental impact on his desire to share these feelings in the future (Table 5, quotes 8 and 9).

Personal continuity

During their family member's/friend's involuntary admission, participants reported being contacted by various professionals about their family member/friend in a way that felt impersonal. Participants described feeling like another ‘case’ to professionals rather than a person who is struggling (Table 5, quote 10).

Because of this, participants reported wanting to receive support from a single, consistent person (Table 5, quotes 11 and 12). Participants reported that having this single person to provide support could help them to develop a relationship that felt sincere, personal and connected (Table 5, quote 13).

Peer support and guidance

Participants consistently communicated that carers should be in contact with peers during their family member's/friend's involuntary psychiatric admission. They reported needing support and guidance from peers because of the knowledge these peers have likely obtained from their previous experience. Supporting quotes can be found in Table 6.

Table 6 Theme 4: peer support and guidance

Peer interaction and support

Both participants who had and had not received support from peers during their family member's/friend's involuntary admission highlighted the need for all carers to receive this type of support. Participants reported feeling isolated during their experience, primarily because of a lack of understanding from others (Table 6, quotes 1 and 2), and so wanted someone who could understand their experience whom they could connect with (Table 6, quotes 3–6). Participants wanted to feel reassured by those who had been through a similar experience, and to understand the coping strategies peers used during their family member's/friend's treatment to inform their own (Table 6, quotes 7 and 8).

The level of understanding that a peer can offer through their experience of supporting someone who has been involuntary admitted to hospital was highly valuable to participants, and was seen as additional to professional support (Table 6, quotes 9–11).

Similarities between carers was also noted as an important consideration for peer support. One participant noted that having a similar relationship with a family member/friend was important for mutual understanding between peers (Table 6, quote 12). Another participant discussed wanting more people from a South Asian background in attendance at group meetings, particularly those who also felt some level of privacy around their family member's/friend's admission (Table 6, quote 13).

Guidance through the caregiving experience

Participants also reported wanting guidance around the mental healthcare system from those who have been through the system before. Although this was highlighted as something that could be useful for any carer, particular importance was placed on those whose family member/friend had been involuntarily admitted for the first time, as participants noted how distressing the first-time experience can be (Table 6, quotes 14 and 15).

Participants also noted how the complexities surrounding involuntary hospital admission can feel extremely overwhelming for those dealing with a first admission, and how it would be useful to have someone with that knowledge to provide some direction (Table 6, quotes 16–18).

One participant also highlighted how empowering it may be for carers to learn how to navigate the mental healthcare system from those who have inside knowledge, allowing them to gain more understanding of the caregiver role (Table 6, quote 19).

Discussion

Summary of findings

Carers of people treated under the MHA report that the support received during admission is generally unstructured and inconsistent, with some carers receiving no support at all. Carers identified three simple needs that, if addressed, could improve the current support offered to this group. The first is the need for carers to receive more information about mental health services, including the treatment provided within these services, and for this to be clearly communicated via a named contact. The second is the need for personal continuity in the delivery of emotional support to allow carers to feel a sincere connection and sense of comfort in confiding about their feelings. The third need is for carers to receive peer support to help them feel reassured and understood in their experiences.

Comparison with literature

Carers reported the need for continuity around both an information and support contact during their family member's/friend's involuntary hospital admission. The need for continuity regarding support aligns with previous qualitative research where patients and clinicians reported that personal continuity of care could improve the quality of the relationship with the clinician and enhance holistic care.Reference Klingemann, Welbel, Priebe, Giacco, Matanov and Lorant21 Challenges to this may be posed by the fact that often information about a carer's patient under treatment is provided through multidisciplinary teams (MDT), making it difficult for carers to receive information from a consistent contact, as each professional is likely to know different information depending on their speciality.Reference Anantapong, Davies and Sampson22,Reference Kutash, Acri, Pollock, Armusewicz, Serene Olin and Hoagwood23 One solution for this may be to have a single person attend MDT meetings (carers in the current study suggest a carer advocate) and feed back the information to carers.

The feeling of isolation carers reported in the current study reflects previous qualitative findings examining carers’ experiences of their family member's/friend's involuntary hospital admission.Reference Stuart, Akther, Machin, Persaud, Simpson and Johnson2,Reference Jankovic, Yeeles, Katsakou, Amos, Morriss and Rose3 Peer support may be one avenue to address this feeling of isolation, with carers in the current study reporting wanting support from people with similar experiences. The ability to interact and receive support from peers was found to be highly beneficial in studies examining patients with an acute episode of mental illness.Reference Johnson, Lamb, Marston, Osborn, Mason and Henderson24 Previous research also highlighted the benefit of carer support groups, reflecting carers’ feelings toward this type of support in the current study.Reference Worrall, Schweizer, Marks, Yuan, Lloyd and Ramjan8 The social identity theory may help to understand these findings, positing that a sense of belonging to a group can have a positive influence on an individual's self-esteem.Reference Leaper25

The need for emotional support highlighted by carers in the current study aligned with previous qualitative findings from the nearest relatives of people who have been involuntarily admitted to hospital under the MHA (a family member who holds specific responsibilities and power for someone detained under the MHA).Reference Dixon, Stone and Laing9 Both studies suggest that this support be offered more widely to carers. The current study's findings also suggest the need for the support offered to be formalised and provided by trained individuals, potentially those with previous experience of supporting someone treated under the MHA. A formal emotional support service could help to increase its scope and further ensure that carers’ support needs are met.

The importance of sharing information with carers about their family member's/friend's hospital treatment has also been emphasised in previous qualitative literature,Reference Jankovic, Yeeles, Katsakou, Amos, Morriss and Rose3 with confidentiality being cited as a key consideration to how much information can be shared. Jankovic et alReference Jankovic, Yeeles, Katsakou, Amos, Morriss and Rose3 described information sharing as a delicate balance between giving carers more information and ensuring patient confidentiality. It has been suggested that general information around patients’ treatment that builds on what carers already know about their family member/friend can be shared without patient confidentiality being broken.Reference Slade, Pinfold, Rapaport, Bellringer, Banerjee and Kuipers26 This aligns closely with carers’ views in the current study. It is important that professionals are aware of the type of information they can share with carers without breaching patient confidentiality, and that carers are aware of the type of information they can receive about their family member/friend or reasonably request.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore what support carers would like to receive during their family member's/friend's involuntary hospital admission. Interviews were conducted at three sites in England, which were all markedly different in their population density, diversity and deprivation levels, enhancing the representativeness of the study sample.27–29 All interviews were coded by four multidisciplinary researchers, and carers with experience of supporting someone who had been involuntarily admitted to hospital were involved in study development and analysis.

However, there are some limitations. There is potential for selection bias in terms of the carers who access this type of research, with underserved carers being less likely to have access to this type of research. Additionally, the sampling method used in this study (purposive sampling) may limit the generalisability of the findings.Reference Andrade30 Although efforts were made to recruit a more diverse sample, including reaching out to communities of typically underrepresented groups and approaching personal contacts of lived experience and professional members involved in the study, we received interest mainly from those who were either female or of White British ethnicity, meaning that their voice and preferences are represented more strongly than other groups. Further research is needed to capture the perspectives of more diverse communities. To help capture these perspectives within this field and across other research, further work should be done examining decision-making factors for participating in research across various communities and across a male demographic. All the interviews were conducted online meaning that the rapport generally obtained through face-to-face contact may have been missed. However, online interviews have been found to elicit notable rapport and rich data.Reference Keen, Lomeli-Rodriguez and Joffe31 Finally, we did not ask for feedback from participants regarding their transcripts.

Implications

The current study provides key areas for the provision of support for carers, based on their experiences of the current support offered to them either by the mental health services or through personal contacts. Based on these experiences, the current study's findings show that the support received by carers is unstructured and often either left to chance or informal peer contacts. Key areas of support identified include the need for personal continuity and support from those with lived experience. This could be offered through a formal support programme that provides relevant information and a named contact person, ideally with lived experience. This type of support programme could reduce costs and input required by mental health professionals, who are already under significant strain. Providing support that directly addresses carers’ needs may help to improve their well-being, which could reduce potential long-term costs associated with psychological or physical morbidity in this group. By feeling supported, this type of programme could also lead to carers providing a greater contribution to services than what they already provide.Reference Giacco, Fiorillo, Del Vecchio, Kallert, Onchev and Raboch6,7 We hope that our study findings can be used to inform co-production in the development of a support programme for carers, ensuring that carers’ experiences are considered and utilised from the outset.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, D.G., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient and public involvement representatives, including Debs Smith, Carrol Lamouline, Farzana Kausir, Miss M. Ogden and Katharina Nagel (EX-IN Carer Peer Supporter, Hamburg, Germany) for their invaluable contribution to the design, development and analysis of this study.

Author contributions

I.W. contributed to the formulation of research questions, conducting interviews, analysis of data and writing the manuscript. A.G-M. contributed to the formulation of research questions, analysis of data and reviewing the manuscript. N.O. and E.L.R.T. contributed to the formulation of the interview schedule, analysis of data and reviewing the manuscript. D.G. contributed to the formulation of research questions and the interview schedule, analysis of data and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (grant number: NIHR201707, awarded to D.G.).

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.