Region Jönköping County healthcare system

Region Jönköping County (RJC) provides healthcare to the 365 000 inhabitants of Jönköping County in southern Sweden at 3 hospitals and 40 primary care clinics. The primary care clinics provide the primary mental healthcare in their catchment areas. The departments of psychiatry at the three hospitals, with their in-patient wards and out-patient clinics, provide specialised psychiatric care; they work closely together at the regional level.

The quality improvement approach in Region Jönköping County

The starting point for RJC's quality journey was the early 1990s, when its management took on a ‘quality as strategy’ approach when the healthcare sector in Sweden was under pressure because of a national economic crisis.Reference Andersson-Gäre and Neuhauser1 This approach has several important characteristics.Reference Övretveit and Staines2

We use a population health approach, based on the understanding of the correlation between experience of care, population health and per capita cost.Reference Berwick, Nolan and Whittington3 Both the management and evaluation of the service embrace and support patient experience, innovation and learning, in addition to clinical results and cost-effectiveness.

Our view is that all healthcare is co-produced and co-designed with the patients and their families,Reference Batalden, Batalden, Margolis, Seid, Armstrong and Opipari-Arrigan4 therefore a focus on what is important for the patients and their families is key. We have developed ‘peers’, who are experienced patients, who engage the psychiatry departments to support other patients in improvement work. We also use exemplar personas such as ‘Esther’ or ‘Britt-Marie’, who represent various inhabitants in Jönköping County. For example, the question ‘What is good for Esther (or Britt-Marie and her family)?’ leads the design and improvement work in RJC.

We provide education on improvement methods to leaders at all levels and to healthcare staff – another crucial aspect of our improvement work. Qulturum, the improvement and innovation centre of RJC, is staffed by improvement leaders, who support improvement work across RJCReference Bodenheimer, Bojestig and Henriks5 (Box 1). The Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare supports education and research as parts of the quality strategy. The Academy is a centre for education and research in management and improvement in the health and welfare sector established by RJC in cooperation with the 13 municipalities and Jönköping University.

Box 1. Methods and programmes that have been/are taught at Qulturum

• Clinical microsystems

• Improvement tools such as plan–do–study–act (PDSA), fish-bone diagrams and driver diagrams

• Leadership for improvement – for leaders at all levels

• Patient safety for management teams

• Access programmes

• In collaboration with Jönköping Academy, courses in:

• leadership for improvement

• patient safety

• co-production/co-design

Websites for more information:

Qulturum: https://plus.rjl.se/qulturum

Jönköping Academy for Improvement of Health and Welfare: https://center.hj.se/jonkoping-academy/om-oss.html

The microsystem concept (where patients, families, care teams and data work together to improve care) is used and is widely taught to staff to support the continuous improvement work at the sharp end: a crucial concept in RJC quality management.Reference Nelson, Batalden and Godfrey6 Continuous non-hierarchical dialogues are used for feedback and learning following improvement work, between each level of the system; this is an important mechanism for sustaining the culture.

Improvement work in mental healthcare

Improvement methods and initiatives have also been adopted in mental healthcare in RJC, illustrated here by an example from specialised psychiatric care.

Psychiatric home treatment teams

Home treatment teams have been established to provide specialised psychiatric care in the patient's home as a part of a community-based psychiatric service. A local trigger for the initiative was positive experiences in a nearby healthcare region and in one of our local departments that had already established mobile teams. Our goal was to move in-patient care, when judged safe and possible, to out-patient-oriented work with increased proximity and flexibility. The value and benefit to the patient are presumed to be a more person-centred care with increased continuity and safety by reducing: duration of hospital care, avoidable hospital admission and avoidable readmissions. Eligible patients are those in need of specialised psychiatric care who would otherwise have been admitted, or patients who are in hospital care where an earlier discharge is possible if care can be provided in their homes.

One specific aim was to reduce in-patient care and prevent hospital admissions by strengthening the out-patient care. Earlier studies have shown that specialised psychiatric home care by mobile teams can improve care, for example by increasing patient satisfaction, reducing stigma connected to psychiatric admission and reducing acute in-patient admissions by 30%.Reference Johnson7

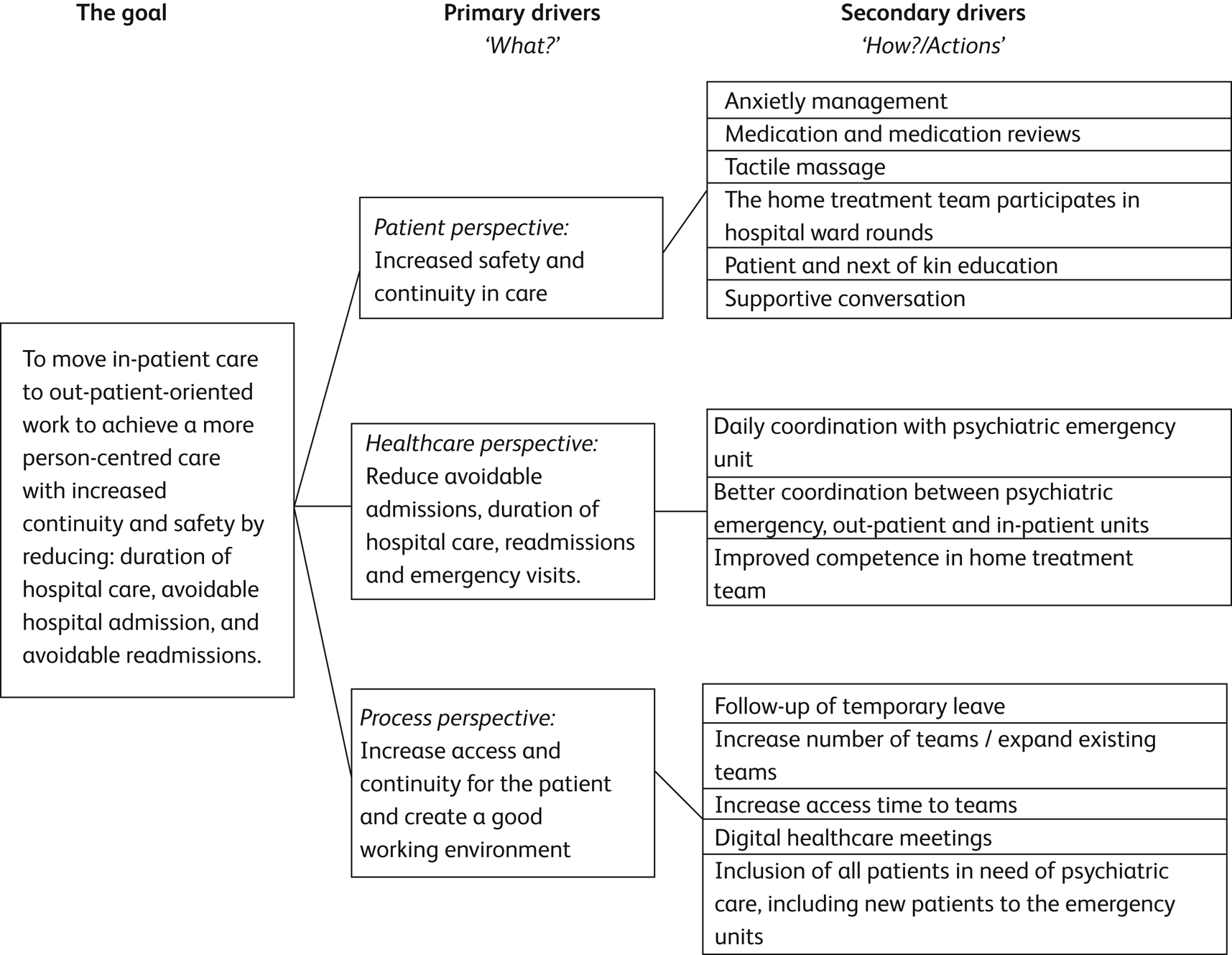

First, a multiprofessional regional quality improvement (QI) team, as well as local implementation teams in each department of psychiatry, were established. Peers, experienced patients and a skilled improvement advisor were also part of the QI team. Initially, they started by analysing the current situation in the different departments. Patients and different professionals were interviewed to identify gaps in needs and expectations, but also about new ideas on how to improve the care provided. The team studied existing mobile psychiatric teams in other healthcare regions. Several improvement tools were used by the QI team to sort and prioritise between actions, such as fish bone diagrams and driver diagrams before setting up a project plan, an action plan and a communication planReference Nelson, Batalden and Godfrey6,8 (Fig. 1). Small-scale tests according to the plan–do–study–act method were set up and evaluated continuously (weekly by the local implementation team and monthly by the regional QI team).

Fig. 1 Driver diagram for the implementation of home treatment teams. A driver diagram is a visual display of a team's theory of what ‘drives’, or contributes to, the achievement of a project aim and is a tool for communicating with a range of stakeholders where a team is testing and working.8

The concept of home treatment teams was developed across the three departments of psychiatry, but the local implementations were developed separately according to the local context. Some differences in staffing and services were accepted.

Care provided by the new home treatment teams includes: medication management, supportive conversation, anxiety management, massage, and education for patients and next of kin. Most of the teams are staffed by assistant nurses and nurses specialised in psychiatry, but other professionals, including psychiatrists, are available if necessary.

A preliminary evaluation of the first 45 patients included at one hospital has been made. Visits to the emergency department per patient in the 90 days after support from the home treatment team was initiated compared with the 90 days before decreased (number of visits after support initiated, median (range): 1 (0–6) v. before, 1 (0–8)). Hospital admissions per patient after support was initiated also decreased (after, 0 (0–7) v. before, 1 (0–11)), as did mean hospital stay per patient after support was initiated (after, 0 (0–57) days v. before, 9 (0–52) days). All differences are significant (α < 0.01, two-sided test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). In a survey, patient satisfaction was high.

According to a survey among staff the establishment of the home teams led to a higher focus on and understanding of the patient's needs and abilities, but also increased interaction with next of kin. Home visits had also contributed to the identification of problems in transitions between hospital and home. Recognising these deficiencies contributed to valuable learning for improvement, as it allowed problems to be addressed at an earlier stage.

Reflections on improvement in mental health

RJC's ‘quality as strategy’ management principle is used in all improvement work across mental healthcare: access to treatment, patient involvement, reducing the need for hospital admission, organisational development of teams, and many others areas. Using this approach to improvement has led RJC to be recognised for its ongoing work with quality in healthcare and for its successful long-term, system-wide improvement. In several national comparisons over the years, the RJC stands out as one of the top healthcare systems in Sweden for clinical results and quality, patient satisfaction, public trust in the healthcare system and financial results.

In our experience, the improvement methods used for physical healthcare can be successfully employed in mental healthcare. This has also contributed to an insight that measurements of effects of improvement efforts are possible and necessary also in mental healthcare. The challenges that remain include: strategies to identify the patient's needs more accurately, difficulties in understanding how different healthcare professionals can contribute, language barriers – to be able to care for non-Swedish-speaking patients. We aim to further develop our culture of co-producing care across the whole system, including patients and next of kin in the co-design of all our improvement activities.

Author contributions

All four authors contributed to the conception of the article. A.R. and A.Ö. drafted the first versions of the article, all four authors then revised it and gave input to its final version. A.R. finalised the article, which was the finally approved by the other authors. All four authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2020.37.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.