Personality disorders are characterised by enduring maladaptive patterns of behaviour, cognition and inner experience, exhibited across many domains and deviating markedly from those accepted by the individual's culture.Reference Potter1 Comorbidity of personality disorder with other mental disorders is common, and the presence of personality disorder often has a negative effect on treatment outcome. Personality disorder is associated with premature mortality and suicideReference Tyrer, Reed and Crawford2 and people with the disorder often use services heavily,Reference Bender, Dolan, Skodol, Sanislow, Dyck and McGlashan3 leading to calls for improved identification in clinical practice.Reference Soetman, Hakkaart-van Roijen, Verheul and Busschbach4

Prevalance of personality disorder

The prevalence of personality disorder increases with levels of care. In the community, estimates range from 4.4% in the UK,Reference Coid, Yang, Tyrer, Roberts and Ullrich5 6.1% in a World Health Organization (WHO) study across 13 countries,Reference Huang, Kotov, de Girolamo, Preti, Angermeyer and Benjet6 to 8.6% in Bangalore.Reference Sharan7 Prevalence of personality disorder is 24% in the UK at the primary care level.Reference Moran, Jenkins, Tylee, Blizard and Mann8 At the secondary care level, psychiatric out-patient prevalence rates varied between 40 and 92% in Europe, 45–51% in the USA and 60% in Pakistan.Reference Beckwith, Moran and Reilly9

Personality disorder is under-diagnosed in routine practice compared with when structured instruments are used.Reference Zimmerman and Mattia10 A USA study showed 31% of psychiatric in-patients met criteria for personality disorder, but only 12.8% of them had a chart diagnosis of personality disorder.Reference Leontieva and Gregory11 In the UK, there is a reported prevalence rate of 7% of admissions in general adult psychiatry wards based on routine case note diagnosis.Reference Dasgupta and Barber12

Review of literature

We searched the PubMed, PscyInfo and EMBase databases using the search strategy ‘personality’ AND ‘disorder’ AND ‘prevalence and ethni*’. We found 10 relevant results and hand-searched references of these papers for additional relevant studies. A meta-analysis (which identified 391 relevant publications and finally included 14) showed significant differences in prevalence between different ethnic groups, raising the question of whether there is a neglect of diagnosis in some ethnic groups or whether these are genuinely differing rates. However, the study does highlight the paucity of research into the prevalence rates of personality disorder among different ethnic minorities.Reference McGilloway, Hall, Lee and Bhui13 A study based on a national household survey suggests that the prevalence of personality disorder is at least similar in minority populations to the native population within the UK.Reference Crawford, Rushwaya, Bajaj, Tyrer and Yang14

Local context

London is one of the most ethnically diverse cities in the world, and East London is the most ethnically diverse part of London with 73% of the population being non-native in origin. East London contains 8 out of the top 15 constituencies in the UK with the highest diversity index scores,15 making it a useful area for investigating whether there is an ethnic variation in prevalence of illness. Within the data gathering period, East London National Health Service Foundation Trust provided services to three boroughs – Tower Hamlets, Newham and City and Hackney – comprising a population of 815 000.16 This audit and service evaluation was undertaken in partnership with the Trust as a quality improvement initiative.

Objectives

The objectives of this audit were:

1. to describe the ethnic variation of psychiatric in-patients with a personality disorder diagnosis in East London;

2. to contrast services such as old age, adolescent, forensic and general adult services.

Method

Anonymised data from routine service contact were collected from the Trust's electronic patient record system on all admissions between April 2007 and April 2013. Ethnicity categories from the 2001 UK census were used. These data were then compared to census data of local demographics from the census data of 2011. Individual identifiers were not examined because routine clinical data were used in aggregate. As this was a service audit to inform our quality improvement initiatives, ethical approvals were deemed to not be necessary.

Results

Out of a total of 19 102 in-patient admissions in 6 years across three boroughs in all services, 1853 of them had or were eventually given a diagnosis of a personality disorder, which gives us a mean prevalence estimate of 9.7%. Of these in-patients, 56% were female and 44% male. This mean prevalence varied from 3% in Indian and Pakistani populations, to 17% in the native White British population (Table 1). There is a statistically significant lower prevalence of personality disorder in all ethnicities compared with the White British population, except in those of mixed race heritage where the sample size is too small. There was little variation in personality disorder diagnosis rates between Black and other minority ethnic (BME) groups where there was a sufficiently large sample size.

Table 1 Mean period prevalence of personality disorder diagnoses in in-patients in the years 2007–2013

Table 2 shows the breakdown of the prevalence of personality disorder diagnosis in the different directorates of the Trust. The prevalence was 20% in forensic, 11% in general adult, 8% in adolescent services and 2% in old-age in-patients. Table 3 compares admission rates to the local population levels of each ethnicity.

Table 2 Prevalence of personality disorder diagnosis in adult, child and adolescent, old-age and forensic services

Table 3 Comparison of admission rates to local population levels

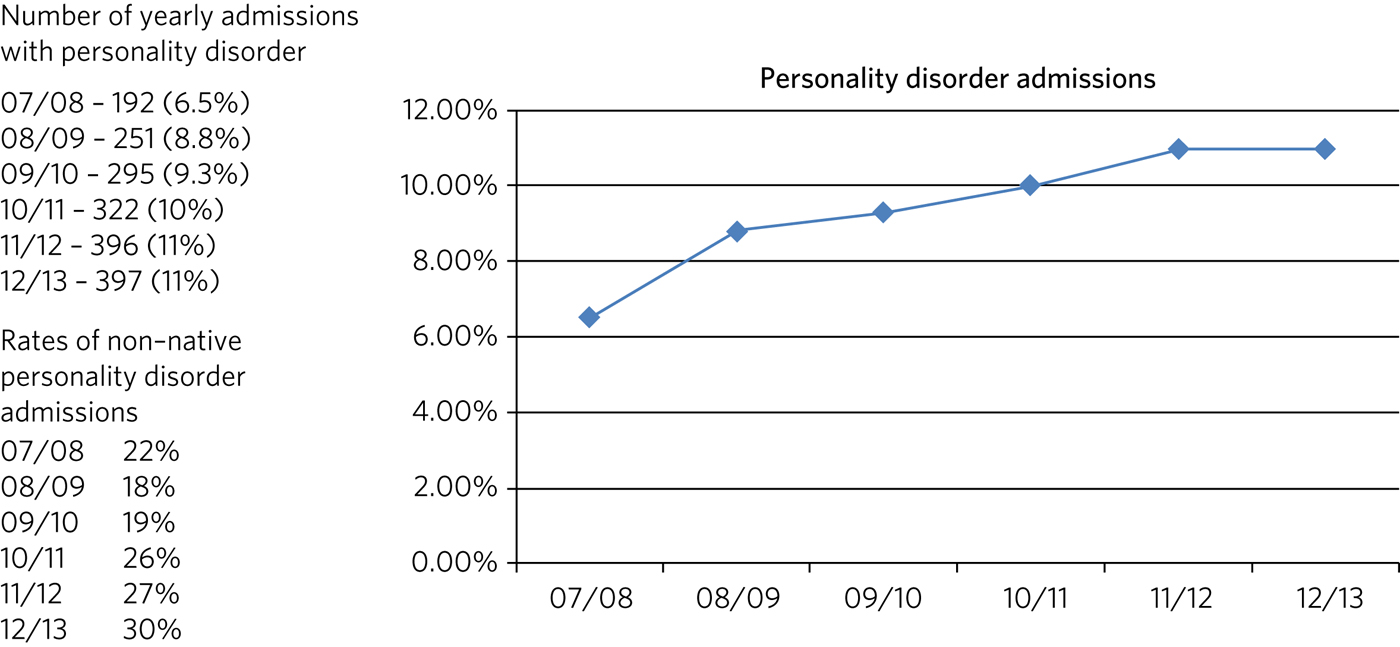

The number of people admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of personality disorder has increased year on year, nearly doubling at the end of the 6 year period (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Number of yearly admissions of people with personality disorder.

Discussion

Our analysis of in-patients in East London demonstrated a 9.7% prevalence rate of personality disorder, which is in line with previous studies of in-patients in the UK.Reference Dasgupta and Barber12

Although our results indicate little variation in personality disorder rates between different BME groups, they consistently show lower rates compared to the White British population. Lower rates of referrals for BME groups to the local personality disorder service have also been found.Reference Garrett, Lee, Blackburn, Priestly and Bhui17 Our findings raise key questions in light of international and national data pointing to the contrary (e.g. the WHO study across 13 countries that found that personality disorder is no less prevalent outside ‘westernised’ countriesReference Huang, Kotov, de Girolamo, Preti, Angermeyer and Benjet6 and the UK surveyReference Crawford, Rushwaya, Bajaj, Tyrer and Yang14). However, the lower incidence of personality disorder presentations in psychiatric emergencies in ethnic minorities has been noted before.Reference Tyrer, Merson, Onyett and Johnson18

Possible reasons for our findings may include that BME community structures contain the mild to moderate presentations of the disorder, meaning that only those people with extreme cases present to mental health services. BME communities also have difficulties in accessing healthcare, more complex pathways to specialist treatmentReference Bhui, Stansfeld, Hull, Priebe, Mole and Feder19 and lower rates of accessing healthcare than the majority of the population.Reference Sashidharan20

There is some evidence that there are ethnic variations in the presentation of the disorder,Reference Selby and Joiner21, Reference Manseau and Case22 that specific symptoms can be shaped by cultureReference Paris and Lis23 and that individuals of differing ethnicity may present with different patterns of personality disorder pathology.Reference Iwamasa, Larrabee and Merritt24, Reference Chavira, Grilo, Shea, Yen, Gunderson and Morey25 In the key population group in East London, there is insufficient consistent evaluation into prevalence, recognition and service access for people with personality disorder from Asian populationsReference de Bernier, Kim and Sen26 and studies showing low rates of personality disorder in Asian-origin samples may be a result of a lack of understanding of what constitutes personality and personality disorder in Asian culture.Reference Ryder, Sun, Dere and Fung27 Differences in the presentation of symptoms of personality disorder in different cultures would not adequately be screened for by the tools currently in use. The preceding factors raise the possibility of misdiagnosis and suboptimal treatment.Reference De Genna and Feske28 In addition, ‘reverse racism’ may be occurring, with psychiatrists reluctant to make a diagnosis of personality disorder because it may be perceived as racist.

The annually increasing number of personality disorder diagnoses may reflect an increased willingness to diagnose this condition due to the increase in evidence-based treatment and the publication of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines on personality disorders in 2009. However, it is interesting to note that the proportion of patients admitted under sections of the Mental Health Act (2007) (MHA) has been steadily increasing since at least 2009 (http://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/major-report/monitoring-mental-health-act-report#old-reports), and there could possibly be a correlate, especially after the changes introduced to the act in 2007.29 Our analysis did not pick out whether the people diagnosed with personality disorder were informal or under a section of the MHA.

The prevalence of 8% of adolescent in-patients with a diagnosis of a personality disorder is remarkable, as ICD-10 (1992) discourages the diagnosis in under 18s.30 This suggests that clinicians may find the diagnosis of heuristic value. There has been considerable evidence that the diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder (and other personality disorders) are as valid, reliable and stable before age 18 as after age 18.Reference Chanen, McCutcheon, Jovey, Jackson and McGorry31

The prevalence of personality disorder among older people in the community has been estimated to be about 10%.Reference Abrams and Horowitz32 Among older in-patients, personality disorder has been seen in 6% of those with organic mental disorders and 24% of those with major depressive disorder.Reference Kunik, Mulsant, Rifai, Sweet, Pasternak and Zubenko33 Our finding of a 2% prevalence suggests that personality disorder may be under-diagnosed significantly in routine practice in old-age patients.

Limitations

Data were collected from one Trust in the UK. However, it is the most ethnically diverse one (Census 2011)16, and there is no reason to expect differences in routine diagnostic practice in other Mental Health Trusts in the UK. We do not anticipate problems relating to quality and validity of the personality disorder data compared with other diagnostic groups because all diagnoses are made on the basis of routine clinical care provided by the Trust.

Recommendations

The significant and rising proportion of in-patients diagnosed with personality disorder, combined with cost and pressures on in-patient beds, indicates that variations in recognition, access and management of these patients needs to be understood to ensure accurate identification and an improvement in present services.

Research targeting reasons for the lower diagnostic rates of personality disorder in BME groups could include whether there are cultural norms shared between BME communities that limit seeking help from mental health services for symptoms of personality disorder, whether there are variations in pathways to care, or whether there are variations in the attitudes of clinicians in diagnosing personality disorder in different ethnic groups.

The high proportion of adolescent in-patients diagnosed with personality disorder highlights the importance of a good transition from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services to adult services, especially given difficulties these patients have with attachment. The ongoing presence of personality disorder in old-age services indicates the need for expertise in detecting and managing this diagnosis in these services, as these patients may represent the most difficult of personality disorder presentations in terms of not having ‘burnt out’ as is often expected.

There is a role for well-designed databases that lend themselves to ongoing analyses of routinely collected clinical data reflecting real service activity. All our results and inferences were obtained from such data, which provides us a low-cost opportunity for comparison over time and in different regions.Reference Kane, Wellings, Free and Goodrich34 These data inform our quality improvement actions to improve clinical skills in assessment and management of personality disorder, and to better understand the needs of adolescents and elderly people with personality disorder.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Information Department of the East London National Health Service Foundation Trust for their excellent help in routine data retrieval. A poster presentation of preliminary results was presented at the 3rd World Congress of Cultural Psychiatry in London on 9–11 Mar 2012.

About the authors

A. Hossain, MRCPsych, Consultant Psychiatrist, North East London National Health Service Foundation Trust, UK; M. Malkov, MRCPsych, ST5 CAMHS Specialty Spr, Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, UK; T. Lee, FFCH, MRCPsych, Consultant Psychiatrist in Psychotherapy, Deancross Personality Disorder Service, East London National Health Service Foundation Trust, UK; K. Bhui, MD, FRCPsych, Professor of Cultural Psychiatry and Epidemiology, Queen Mary University of London and Honorary Consultant Psychiatrist, East London National Health Service Foundation Trust, UK.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.